The Next Decade of Discovery in Solar and Space Physics: Exploring and Safeguarding Humanity's Home in Space (2025)

Chapter: Appendix C: Report of the Panel on the Physics of Magnetospheres

C

Report of the Panel on the Physics of Magnetospheres

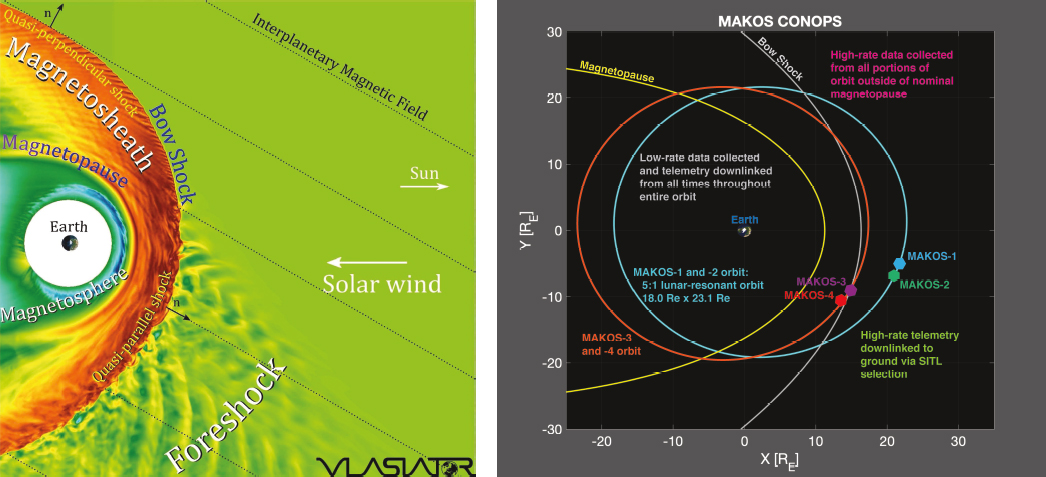

The magnetosphere, the region of space where the magnetic field is dominated by the contribution from a planet’s internally generated field, is filled with charged particles of energies ranging from less than an electron volt (eV) to hundreds of megaelectron volts (MeV) that are transported and accelerated by magnetic and electric fields. Figure C-1 illustrates the main regions of the magnetosphere. Magnetospheres are dynamic systems owing to the interaction with the solar wind and interplanetary magnetic field (IMF), and the connections to the atmosphere and ionosphere close to the planetary surface as well as the influence of planetary satellites. All planets and moons with intrinsic magnetic fields have magnetospheres, but the most familiar and most studied example is Earth’s magnetosphere.

Magnetospheric physics is the study of this interconnected system. The science involves understanding how different particle populations enter the magnetosphere and how they are heated, accelerated, and transported within the magnetosphere, either flowing through the magnetosphere or becoming trapped. It involves understanding both how the steady-state configuration of the magnetosphere is formed and maintained and the dynamic changes that occur. Strong, sustained southward interplanetary magnetic fields drive geomagnetic storms, which result in intense currents both around Earth (the ring current), along the magnetic field lines, and through the ionosphere, causing magnetic disturbances on the ground. Geomagnetic storms can also increase the radiation belt flux that can damage spacecraft and can affect the ionosphere, disrupting global positioning system (GPS) navigation. Studies of magnetospheric dynamics will lead to better understanding and predictions of the impacts of solar and solar wind variability on Earth, life, and society.

Planetary magnetospheres—especially that of Earth—are also accessible laboratories for studying the fundamental physics of collisionless plasmas, including the above-mentioned reconnection, collisionless shocks, turbulence, electromagnetic wave generation, wave–particle interactions (WPIs) and charged particle acceleration. These processes drive the dynamics observed at Earth and other planets, as well as throughout the heliosphere—at the sun, in solar energetic particle events, in coronal mass ejections, at interstellar shocks, and at heliospheric boundaries. In addition, these plasma processes occur throughout the universe, for example in supernova remnants, accretion disks, and astrophysical jets. Earth’s magnetosphere is the most accessible location to study these processes in situ to better understand systems throughout the universe.

Through decades of analysis, researchers have developed a detailed understanding of the global magnetospheric configuration and its response to the solar wind. But the magnetosphere is a large dynamic system, and the wide range of temporal and spatial scales that are important have made it a challenge to disentangle many of

NOTES: The color indicates the density. A magnetic reconnection line can be observed forming in the near-Earth plasma sheet.

SOURCE: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio, the Space Weather Research Center (SWRC), the Community-Coordinated Modeling Center (CCMC), and the Space Weather Modeling Framework (SWMF).

the physical processes. Missions with a few spacecraft have led to tremendous breakthroughs in the understanding of the physics at a particular scale. However, they have also revealed that understanding the full dynamics requires a multiscale perspective and requires better understanding of the linkages between the different regions of the magnetosphere. Other planetary magnetospheres have not been studied with nearly the depth of Earth’s magnetosphere thus many basic questions still remain.

Section C.1 reviews the progress that has been made in the past decade. Section C.2 outlines the priority science goals (PSGs) for the next decade and show how these goals emerged from the current research activity. Section C.3 outlines a longer-range goal. In Section C.4, some emerging capabilities and technologies are identified that can be leveraged to advance the field. Last, Section C.5 outlines a research strategy for addressing the PSGs.

C.1 CURRENT STATE OF THE FIELD

Two major strategic missions—Van Allen Probes (2012–2019) and the Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission (2015–present)—launched and completed their prime missions during the previous decade. These two missions—combined with measurements from other spacecraft in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) Heliophysics System Observatory (HSO), CubeSats, rockets, balloons, international missions, and ground-based assets—have led to substantial breakthroughs in the understanding of the inner magnetosphere, the physics of magnetic reconnection and other fundamental processes, global magnetospheric responses to magnetosphere–solar wind coupling and magnetosphere–ionosphere coupling. In addition, measurements at Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Mars and Venus have all contributed to the understanding of magnetospheric processes in diverse planetary environments. The following sections review the progress in each of these areas.

C.1.1 Inner Magnetosphere

The inner magnetosphere includes different interrelated, overlapping particle populations: the radiation belts at the highest (MeV and above) energies, the hot ring current and warm plasma cloak at lower (few eV to hundreds

SOURCE: From D.N. Baker, S.G. Kanekal, V.C. Hoxie, M.G. Henderson, X. Li, H.E. Spence, S.R. Elkington, et al., 2013, “A Long-Lived Relativistic Electron Storage Ring Embedded in Earth’s Outer Van Allen Belt,” Science 340:186–190, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1233518. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

of keV) energies, and the cold plasmasphere at the lowest (<1 eV) energies. Progress has been made in understanding the formation, acceleration, and loss mechanisms for all these particle populations.

Understanding the dynamics of the radiation belts was a key goal of the Van Allen Probes mission because of the severe space weather impacts this energetic population can have on operating spacecraft. Van Allen Probes showed definitively that local acceleration by wave particle interactions is occurring in the center of the radiation belts, causing fast local changes in the belts. In some cases, both WPIs and the long-studied radial diffusion are needed to explain the observed energization. Other key findings on the radiation belts include the following:

- Large-scale changes in the radiation belts: Observations showed dramatic spatial and temporal variability, including rapid flux enhancements in the outer radiation belt. These observations revealed that large-scale, highly coherent, transient structures can form, such as a third belt, as shown in Figure C-2.

- Radiation belt loss processes: Orders-of-magnitude depletions of the radiation belts were observed to occur in a few hours or less, revealing complex loss processes. Van Allen Probes combined with data from CubeSats and balloons, and models, determined that these are owing to a combination of magnetopause shadowing and precipitation into the atmosphere owing to interactions with plasma waves. These results revealed the importance of studying other mechanisms such as nonlinear WPIs, drift-orbit bifurcations, and field-line-curvature scattering.

- Importance of waves in the inner magnetosphere: Complete orbital coverage and advanced instrumentation enabled mapping of the spatial distribution of wave types (e.g., chorus, hiss, and electromagnetic ion cyclotron) and their parameterization with magnetospheric and interplanetary activity levels. This allowed significant improvements to diffusion-based models. Data assimilation methods were developed for 2D diffusion models.

- Moving toward radiation belt prediction: Novel methods such as observing system experiments (OSEs) and observing system simulation experiments (OSSEs) were recently applied to improve model accuracy, elucidate the belt response to an injection or to a change in the interplanetary driver, and help with future mission planning by optimizing ranges of orbital and sensor parameters. Some radiation-belt models, along with other magnetospheric models, are candidates for the research-to-operations (R2O) pipeline.

For the lower-energy populations there have been significant advancements in understanding how the ionospheric plasma feeds the storm-time ring current. Figure C-3 shows the main transport paths. Both observations and simulations have shown that the near-Earth plasma sheet changes from a solar wind plasma dominated population to an ionospheric plasma dominated population just before or during the storm main phase, and enhanced

SOURCE: Yamauchi (2019), https://doi.org/10.5194/angeo-37-1197-2019. CC BY 4.0.

convection then brings that population into the ring current. In addition, Van Allen Probes measurements showed that mesoscale energetic particle injections associated with magnetic field dipolarizations can also increase the ring current pressure and are also associated with direct outflow of O+ into the inner magnetosphere. This outflow has only a small impact on the ring current pressure owing to its low energy but is likely a source for the warm plasma cloak and perhaps the oxygen torus, a population of warm (<50 eV) oxygen ions located outside the plasmapause. Other key findings include:

- Contributions of ion outflow sources: There is strong auroral outflow in both the dayside cusp and the nightside auroral region during the storm main phase. The nightside auroral outflow is transported to the inner magnetosphere but does not reach high enough energies to affect the energy density. The outflow location of the energetic O+ that populates the ring current is more likely to be the cusp region.

- Minor ions provide diagnostics of outflow mechanisms: Data from the Arase satellite revealed that molecular ions (O2+, NO+, N2+) with energies above ~12 keV are frequently observed in the inner magnetosphere during storm times. The high occurrence rate of molecular ions indicates that fast ion outflows from deep in the ionosphere (<300 km) occur more frequently than expected during storm times.

- The ring current of Saturn: The Grand Finale of the Cassini mission at Saturn explored that planet’s ring current and found it to be influenced by multiple drivers, both external (i.e., the solar wind) and internal (i.e., planetary period oscillations), which trigger magnetospheric storms that result in a partial ring current of hot plasma on the nightside.

At the lowest energies, observations of plasmaspheric material at geosynchronous orbit have shown that the outward convection of this material can persist for weeks, making it a significant loss process for this population. Recent modeling suggests that high-speed outflows on convecting field lines may continue to feed the plume, which could explain its long duration. In addition, charge exchange reactions between energetic ring current ions and the ambient neutral exosphere are efficient enough to provide an additional source for the plasmaspheric plasma.

While this source is not large enough to compensate for the large losses observed, it could lead to a shortened early-phase plasmaspheric refilling period. Additional findings include:

- Measurements of cold electron density: While the core plasmaspheric particles most often could not be measured with Van Allen Probes owing to the spacecraft potential, the density could be determined using measurements of the spacecraft floating potential and the upper hybrid frequency. The large database of density measurements has led to new empirical models of the plasmasphere that are needed for use with radiation belt models.

- Atmospheric loss beyond Earth: New results from Venus and Mars have resulted in estimates of atmospheric loss that are of similar magnitude to that of Earth, despite the total lack and limited protection afforded these atmospheres by these worlds’ respective planetary magnetic fields. This has raised new questions about the validity of the understanding that planetary magnetic fields protect atmospheres from ablation by the solar wind.

C.1.2 Reconnection/Turbulence/Shock

The MMS mission provided the magnetospheric community with unprecedented high time resolution, small spatial-scale observations of reconnection regions in the magnetosphere, both on the dayside and in the magnetotail. As shown in Figure C-4, for the first time, observations directly captured the electron diffusion region (EDR) of magnetic reconnection, where magnetic field lines can break and reform, explosively releasing magnetic energy into bulk flows, heating, and the acceleration of particles, and ultimately allowing solar wind energy to enter the magnetosphere and driving space weather events. MMS discoveries of reconnection include observations of nongyrotropic electron distributions, illustrating acceleration and demagnetization occurring in the region; determination that the reconnection electric field is produced by electron inertia effects at the x-line and by the divergence of the electron pressure tensor at the stagnation point; and relation of the dimensions of the EDR to the gyro-scale of trapped electrons.

Other key findings on fundamental physical processes include the following:

- Collisionless dissipation in multiple environments: For the first time, the dissipation in low-collisionality plasmas was directly measured in different regimes, through new measurements of energy exchange, or by measuring different terms of the collisionless Ohm’s Law.

SOURCE: From J.L. Burch, R.B. Torbert, T.D. Phan, L.-J. Chen, T.E. Moore, R.E. Ergun, D.J. Eastwood, et al., 2016, “Electron-Scale Measurements of Magnetic Reconnection in Space,” Science 352:aaf2939, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf2939. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

- Interplay of reconnection, turbulence, and shocks: Numerous MMS observations have quantified how the quasi-parallel bow shock generates turbulence, which can generate large numbers of current sheets, many of which are reconnecting. Turbulence generated during the reconnection process occurs throughout the reconnection site, and can strongly accelerate electrons, especially in the magnetotail,

- Wide range of large-scale reconnection behaviors: At the mesoscale and global scale, fortuitous conjunctions of missions such as the Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms (THEMIS) and Cluster have provided measurements along the dayside magnetopause demonstrating that reconnection can be widespread, extending over many Earth radii, or limited in spatial extent, potentially active over less than a single Earth radii in one or a series of co-existing patches. Simulation models (two-fluid, particle-in-cell [PIC], and Hybrid Vlasov) have seen similar behavior.

- Impacts of cold plasma and heavy ions: Observations from THEMIS, MMS, and Cluster showed that magnetopause reconnection is affected by cold plasma and heavy ions mass loading the dayside reconnection region. Plasmaspheric plumes transported to the magnetopause as well O+ both from the dayside high-latitude ionosphere and from the warm plasma cloak can reduce the reconnection rate.

- Direct measurement of microscale turbulent cascade: For the first time, energy cascade rates at sub-magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) scales could be measured directly in the turbulent magnetosheath and compared with global-scale cascade rates. The microscale cascade rate was found to be somewhat lower than the global rate, consistent with some theories. Notably, the cascade rate in the magnetosheath is about 1,000 times larger than in the pristine solar wind.

- Fundamental processes beyond Earth: Turbulence has been discovered in the magnetosheath at Jupiter, magnetosphere of Saturn, and near the Venusian bow shock. New observations have advanced understanding of the drivers, variability, and characteristics of the bow shocks at Mercury, Venus, and Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. In particular, in the latter case of bow shocks, these other planets give access to a range of shock regimes inaccessible at Earth and the solar wind.

C.1.3 Global Magnetospheric Dynamics

Major progress has been made defining the large-scale dynamics of Earth’s global magnetosphere resulting from the coupling with the solar wind, as well as the dynamics of other planetary magnetospheres.

Significant achievements and landmark discoveries over the past decade include:

- Quantifying dynamics of kinetic shock structures: THEMIS multipoint measurements provided the first observations of a now commonly seen structure called a foreshock bubble. These large structures accelerate charged particles locally and flow downstream where they collide with the magnetosphere, depositing energy into the system.

- Kelvin-Helmholtz energy conversion: Long-term studies using THEMIS data revealed that dynamic nonlinear Kelvin-Helmholtz waves occur at Earth’s magnetopause boundary much more frequently (as much as 20 percent of the time) than originally thought. Building on this discovery, the community made novel measurements identifying the long-ranging effects of these twisted magnetic structures—for example, releasing energetic particle injections and seeding ultra-low frequency waves that echo throughout the magnetosphere.

- Magnetotail transport and dynamics: A growing number of multisatellite studies leveraging serendipitous arrangements of magnetospheric assets (e.g., THEMIS, Van Allen Probes, MMS, Arase, Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites [GOES], and Los Alamos National Laboratory [LANL] satellites) along with ground assets (e.g., riometers, all-sky-imagers, magnetometers) in the past decade have begun to constrain the azimuthal-scale size of energetic particle injections, as illustrated in Figure C-5. Injections, sudden increases in energetic particle fluxes close to geosynchronous orbit, are associated with the range of phenomena (e.g., bursty bulk flows, dipolarizing flux bundles, dipolarization fronts) that accompany the reconfiguration of the tail following reconnection, and so help to identify the spatial scales of global magnetotail dynamics.

SOURCE: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio.

- Energetic particle acceleration: Modeling studies, constrained by data from missions including THEMIS and MMS, have discovered that coherent dipolarization fronts or dipolarizing flux bundles can carry energetic electrons and ions earthward by trapping them in drifts around localized “magnetic islands.” This may play an important role in the energization and transport of particles from the tail into the inner magnetosphere.

- Structure of the substorm current wedge: New results from THEMIS, ground-based magnetometers, and all-sky imagers (ASIs), and models over the past decade have introduced multiple conflicting hypotheses for the structure of the large-scale substorm current wedge, the electrical current system that connects the magnetosphere to the ionosphere. The hypotheses include that it is one large system, as previously thought; that it originates from the pileup of multiple mesoscale structures; and/or that it is composed of multiple “wedgelets” that form simultaneously and continuously. These models provide advancement in understanding but also motivate some of the science questions for the next decade.

- Solar wind-magnetosphere coupling beyond Earth: New results from the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission at Mars and Juno at Jupiter have provided evidence of magnetic reconnection at the dayside crustal magnetic fields and the planet’s dayside magnetopause, respectively. Conversely, new theoretical studies of the Ice Giants, Uranus and Neptune, suggest that the nature of the solar wind–magnetosphere coupling of these worlds may be driven more by viscous-like interactions rather than reconnection.

- Magnetotail dynamics beyond Earth: Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) provided the first direct observation of substorm-related impulsive injections of electrons at Mercury. Likewise, reanalysis of Voyager 2 observations at Uranus found evidence of a tailward-directed plasmoid likely resulting from magnetotail reconnection.

C.1.4 Magnetosphere–Ionosphere–Thermosphere Coupling

The magnetosphere and ionosphere/thermosphere are coupled through a myriad of processes that affect the dynamics of both regions, as illustrated in Figure C-6. These processes occur on a range of spatial and temporal scales, with the possibility of cross-scale coupling; for example, long-term/global-scale processes affecting the development of shorter-duration/small-scale phenomena, and vice versa. Major progress has been made in understanding the transfer of mass, momentum, and energy between the magnetosphere and ionosphere/thermosphere.

Significant achievements and landmark discoveries over the past decade include the following:

- Kinetic and electromagnetic energy deposition in the ionosphere and thermosphere: Patchy processes with transverse scales in the topside ionosphere (100 km can be associated with extreme Poynting fluxes >170 mW/m2. There is an ongoing debate on the importance of these processes relative to larger-scale

SOURCE: Used with permission of The Royal Society (United Kingdom) from T.E. Sarris, 2019, “Understanding the Ionosphere Thermosphere Response to Solar and Magnetospheric Drivers: Status, Challenges and Open Issues,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 377(2148):20180101, http://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0101; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

- processes in determining global energy deposition rates, heating, and dynamics. In addition, it was shown that substantial electromagnetic/kinetic energy input and related ionosphere–thermosphere heating can occur outside major geomagnetic storms and at a range of altitudes. This high-latitude energy deposition can alter thermospheric wind circulation and lead to thermospheric composition change, which then affects the ionospheric density.

- Multiscale electrodynamic and mass coupling: The occurrence of dramatic enhancements in mid-latitude ionospheric convection flows are linked to the occurrence of an optical emission called STEVE (strong thermal emission velocity enhancement) and finally to structured flows and waves in the magnetosphere. In addition, the penetration and shielding electric fields from the magnetosphere during geomagnetic storms play a crucial role in the formation and evolution of the ionospheric density structures, such as the storm-enhanced density (SED) plumes and polar cap patches. These high-density structures have been shown to supply large fluxes of ionospheric heavy ions to the magnetosphere, which in turn can affect the magnetospheric dynamics, such as reconnection and ring current ion composition.

- The causes and consequences of north-south and east-west asymmetries: It was found that asymmetries dramatically alter the nominal structure of ionospheric convection patterns, large-scale current systems, wave activity, and geomagnetic disturbances. The sources of asymmetries include Earth’s offset dipole, seasonal variations in solar illumination leading to north-south hemisphere asymmetries in high-latitude energy deposition and ionospheric conductance, and asymmetries in solar wind driving conditions imposed on the magnetosphere–ionosphere system.

- Imaging magnetospheric processes with the aurora: New abilities to remote sense the magnetospheric dynamics using the aurora have been unlocked through analyzing the connections between magnetospheric processes, energy and species-dependent particle precipitation, and multiwavelength aurora. For example, discoveries have linked pulsating and diffuse aurora to a range of plasma wave dynamics in the inner magnetosphere.

- A new era of understanding magnetosphere–ionosphere coupling at Jupiter: The Juno mission provided the first in situ investigations of the poles of Jupiter. This revealed the presence of phenomena-like ion conics similar to those seen at Earth, but with others much more extreme, like megavolt electric potentials. These results have opened new debates as to whether these extreme polar acceleration regions may actually serve as a source of Jupiter’s extreme radiation belts.

C.2 PRIORITY SCIENCE GOALS FOR MAGNETOSPHERIC PHYSICS

Section C.1 highlights the tremendous progress that has been made in the past decade, particularly in understanding the dynamics of the radiation belts and the microphysics of magnetic reconnection. But the past decade has also revealed areas with significant open questions. First, it has become apparent that that the coupling between systems in the magnetosphere affects the global dynamics. While substantial previous work has focused on understanding the behavior in specific regions—such as the inner magnetosphere, the magnetotail, the magnetopause boundary, or the low-altitude auroral zone—each of these regions interacts with and affects the rest of the system. The links between these systems are in many cases not well understood. It has also become clear that much of the important dynamics are occurring at scales that are not well sampled. Most of magnetospheric dynamics is driven by magnetic reconnection-associated processes at the magnetopause and in the magnetotail. While the global scales of this interaction are understood, and the microscales have now been explored in detail with MMS, it is not yet understood how the microscale processes are initiated and how the regions around them evolve, ultimately leading to the observed global-scale dynamics.

It has also become evident that the contribution and impacts of the ionospheric source to the magnetosphere is not well understood. There is a cold ion component that dominates the density in much of the magnetosphere but is difficult to measure and so has not been well characterized. The processes that lead to outflow of the ionospheric plasma at different latitudes, how these processes vary with the energy input, and how this variation affects the energy distribution and composition of both the cold and hot components of the outflow still has many aspects that are not known. Furthermore, the impacts of these cold and hot components on various magnetospheric processes, such as WPIs, reconnection, and storm-time dynamics remains to be quantified.

The fundamental question of how particles are accelerated and heated throughout the magnetosphere is only partially resolved. While progress has been made in understanding the acceleration of the radiation belts, and acceleration by reconnection, there is still much that remains unknown.

Last, while Earth provides one example of a magnetosphere, exhibiting dynamics under one set of conditions, other planets provide a wide variety of characteristics that can be used to understand how magnetospheres operate universally. Many of these planets are largely unexplored.

Based on this assessment of unknowns, the panel has framed the following six questions:

- How is the solar wind energy input to the magnetosphere transmitted between different regions and across different scales?

- What are the characteristics, life cycle, and magnetospheric impact of plasma of ionospheric origin—both the cold populations and hotter energetic outflows?

- What controls the multiscale electrodynamic coupling between the ionosphere and the magnetosphere?

- What are the 3D global properties of turbulence, magnetic reconnection, and shocks, and what is their role in coupling energy in the magnetosphere?

- How are particles accelerated throughout planetary magnetospheres?

- How do other planets’ magnetospheric characteristics and configurations affect their magnetospheric processes, interactions, and dynamics?

All these questions are critical for the understanding of magnetospheric dynamics. For the next decade, the first four questions are prioritized. The sixth question, focusing on understanding the magnetospheres of other planets, is a longer-term goal. While there are aspects of this question that can be addressed in the next decade, fully exploring magnetospheric dynamics under all the different conditions represented by other planets requires significant resources beyond what is possible in the next decade. While the general topic of acceleration is not a focus for the coming decade, some important aspects of question 5, targeting particle acceleration, are included under the other questions: in particular, acceleration of ionospheric ions to create ion outflow is included in question 2, and acceleration and heating through reconnection, turbulence and shocks is included in question 4, and dynamics of radiation belts in other systems such as Jupiter is included in question 6. Investigations into all aspects of acceleration in the magnetosphere are still supported. Here the four PSGs are discussed in detail.

C.2.1 Priority Science Goal 1: How Is the Solar Wind Energy Input to the Magnetosphere Transmitted Between Different Regions and Across Different Scales?

The magnetospheric community has answered aspects of this question on global scales—that is, scales that span the width of the magnetotail—and has begun investigating how this occurs on meso-scales and small-scales as well. See Table C-1 for examples of global versus meso-scales in phenomena on Earth’s nightside and Table C-2 for scales on the dayside. Note the scale sizes are defined the same for dayside phenomena. But the results show that significant processes are occurring at spatial scales that are not yet resolvable with current measurements. These processes must be better understood to fully appreciate the complex dynamics. In addition, there are major gaps in the understanding of how energy, momentum, and mass are distributed, because geospace is comprised of several interconnected regimes that display a broad range of spatial scales and response times, and interact with each other with various degrees of feedback, hysteresis, and other aspects characteristic of complex systems. The barrier faced in achieving true system science progress is the lack of a coordinated program that can answer how energy, mass, and momentum are transferred between different regions of the solar wind–magnetosphere–ionosphere coupled system with sufficiently granular resolution to accommodate the broad range of space and timescales involved. Specific objectives required to make progress are given in Table C-3.

Much of the energy that drives geomagnetic and ionospheric disturbances and dynamics is extracted from the flowing solar wind and distributed throughout geospace. Over the past decade, while significant progress has been made in understanding the processing of plasma and flow of energy from the solar wind into the magnetosphere, clear gaps in understanding have emerged. The community has come to the consensus that magnetic reconnection

TABLE C-1 Examples of Global Versus Mesoscale Phenomena on Earth’s Nightside

| Phenomena | Spatial Size | Temporal Size | Additional Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dipolarization | Several hours MLT | Tens of minutes to >hour | Persistent magnetic field increase toward more dipolar; historical substorm indicator in the tail |

| Dipolarizing Flux Bundles | ~1–several RE (in YGSM) | Single DFB: ~40s; Train of DFBs: minutes (at satellite) | Temporal or spatial increases in Bz; typically associated with fast plasma flows |

| Dipolarization Front | ~500–1,000 km (in XGSM) | Seconds (at satellite); minutes to tens of minutes | Increase in Bz preceding a DFB; separates hot plasma inside DFB from cooler surrounding plasma |

| Substorm Current Wedge | Several hours MLT | Tens of minutes to >hour | Current diversion from the tail through the ionosphere; based on ground and space observations |

| Wedgelets | ~1–several RE in azimuth (~YGSM) | Single: ~40s; Train: minutes (at satellite) | Temporally or azimuthally localized wedge indicators; related to mesoscale flows |

| Global Aurora | >1,000 km, can span few hours MLT | Tens of minutes to hours | Auroral oval, large-scale diffuse and discrete aurora |

| Mesoscale aurora | ~10 km–500 km | Minutes to tens of minutes | Streamers, poleward boundary intensifications, etc. |

| Substorm Injection | Up to several hours MLT | Tens of minutes to >hour | Persistent energetic particle flux increases; historically at GEO |

| Mesoscale Injections | ~1–several RE | Tens of seconds (single) to minutes (at satellite) | Temporal energetic particle flux enhancements; observed in the near tail and inner magnetosphere |

NOTE: Acronyms defined in Appendix H.

SOURCE: Gabrielse et al. (2023), https://doi.org/10.3389/fspas.2023.1151339. CC BY 4.0.

TABLE C-2 Examples of Mesoscale Phenomena on Earth’s Dayside

| Hot Flow Anomalies | Spontaneous Hot Flow Anomalies | Foreshock Bubbles | Foreshock Cavities | Foreshock Cavitons | Foreshock compressional Boundaries | Density Holes | Short Large-Amplitude Magnetic Structures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Tens of seconds to minutes | Tens of seconds to minutes | Tens of seconds to minutes | Tens of seconds to minutes | Tens of seconds to ~1 minute | Tens of seconds to minutes | Seconds to ~1 minute | Seconds to tens of seconds |

| Scale size | ~1 to a few RE | ~1 to a few RE | ~1 to a few RE | ~1 to a few RE | ~1 to a few RE | ~1 to a few RE | ~1 to a few RE | Up to 3,000 km |

SOURCE: Zhang et al. (2022), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-021-00865-0.

TABLE C-3 Objectives for Priority Science Goal 1

| Priority Science Goal (1 of 4) | Objectives |

|---|---|

| How is the solar wind energy input to the magnetosphere transmitted between different regions and across different scales? |

1.a. Determine the spatial scale size and extent and the temporal evolution of energy and mass transfer processes at the magnetopause. 1.b. Determine how processes at different spatial scales (kinetic versus mesoversus global scales) transport, store, and release energy in the nightside plasma sheet and into the ring current. 1.c. Determine the connection between multiscale structures in the plasma sheet and discrete structures in the aurora. |

is the primary mechanism for the transfer of energy into the magnetopause, yet it is unknown how this process presents itself spatially across the magnetopause. Under what conditions is reconnection spatially localized versus spatially extended? The spatial extent is closely linked to how much energy is being transferred from the solar wind at any given time. Other structures, such as boundary waves, and boundary conditions within the magnetosphere have also been found to impact the coupling and flow of energy, but their relative importance remains unknown. The role the magnetosphere and its internal plasma populations may play in modulating dayside reconnection remains a major open topic. These gaps in understanding are linked by a common thread: the cross-scale coupling of physics, specifically the link between spatial scales coupling ion- to MHD-scale physics.

In the magnetotail, it is known that after reconnection, most of the magnetic flux is transported via mesoscale (roughly 1–3 RE) fast plasma flows. Those flows and their magnetic structures have been extensively observed and modeled throughout the plasma sheet, but the transition points remain unclear. It is not known what initiates the magnetotail reconnection that starts these meso-scale flows, and what determines their scale size. When those flows reach Earth’s “transition region,” the region between ~6 RE to 12 RE downtail where Earth’s magnetic field transitions from dipolar to stretched field lines, it is not understood how that energy is transmitted: how much goes to the inner magnetosphere, how much is sent to the ionosphere, and how much slides around to the dayside.

To address this question, the primary transition points of interest are therefore the boundary between the solar wind and the magnetosphere (e.g., the magnetopause) to better understand energy transfer from the solar wind to the magnetospheric system, the transition from the plasma sheet to the inner magnetosphere to better understand how the tail supplies the radiation belts and ring current with particles and energy, and the connection between the magnetosphere and the ionosphere as a coupled system.

Current Research Activity

Operating and Past Missions

Many serendipitous spatial arrangements of current (and past) assets have been used to probe how energy is transmitted. For example, the THEMIS mission observed the dipolarization fronts and meso-scale flows that contributed to magnetic flux, particle, and energy transport toward the inner magnetosphere. The three THEMIS satellites closest to Earth have been used to try to constrain particle injection sizes and propagation directions in conjunction with NASA’s Van Allen Probes, Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission (MMS), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA’s) Arase satellite, and LANL and/or GOES satellites at geosynchronous orbit (6.6 RE). Ground-based assets have also been used with these missions, using auroral, riometer, and radar signatures to indicate where the plasma flows and particle injections may be occurring. Even with approximately sixteen satellites serendipitously located to study one event, injection characteristics were difficult to constrain.

Particle transport and heating has also been studied using conjunctions between in situ observations from NASA’s MMS mission and remote observations from the energetic neutral atom (ENA) spectrometers aboard NASA’s Two Wide-Angle Imaging Neutral-atom Spectrometers (TWINS) mission. The TWINS ENA data have been creatively mapped to the plasma sheet to provide a 2D view of the heated plasma flows and compared to MMS data. At a few-minute cadence, however, understanding of temporal evolution is limited. Similarly, NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) provided ENA imaging of the bow shock and magnetosheath to study the energy input into the magnetosphere system. For example, ENA imaging of the plasma sheet location and shape

out to ~16 RE showed a possible tail disconnection event at ~10 RE on the nightside and the bow shock, foreshock, and subsolar magnetopause on the dayside. These ENA images provide context for large-scale structures and global dynamics in the magnetosphere in response to varying solar wind conditions, but the temporal and spatial scales required by this mission (many days) are not sufficient to study dynamic processes at meso-scales.

As a tetrahedron of satellites with separation distances that have ranged from 600–20,000 km, the European Space Agency (ESA) Cluster mission has made great strides in studying how meso-scale structures in the magnetosphere (on the order of 1–3 RE wide) propagate and what their scale sizes are. Cluster has measured the propagation direction and speed of dipolarization fronts at one location but is unable to follow the same magnetic structure along its evolution. Moreover, Cluster studies on this topic are limited as the spacecraft orbits only rarely pass through Earth’s transition region. The ability to follow the same magnetic structure along its evolution would help ascertain where and how the material and energy are transported. Was the magnetic structure/flow channel stopped before it could deposit energy, particles, and momentum in the inner magnetosphere? Did it deposit its information at the boundary of the transition region?

As a tetrahedron of satellites with tens of km separation distances, MMS has revealed kinetic-scale physics—especially related to reconnection—more than any other mission before it. HelioSwarm, a NASA Medium Class Explorer (MIDEX) mission currently in early development, will look at how energy is transferred across different scales. Although its primary focus is the solar wind, it will also spend time in the magnetosphere where it can probe magnetospheric turbulence. With apogee at almost lunar distances and perigee near 15 RE, HelioSwarm will not directly study the energy/mass/momentum transfer from the solar wind to the magnetosphere nor from the plasma sheet to the inner magnetosphere (or ionosphere).

Another mission in development to measure the solar wind and its dynamic interaction with the magnetosphere is the Solar wind Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer (SMILE) mission, a joint effort between ESA and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). Expected to launch in 2025, SMILE will observe the solar wind interaction with the magnetosphere with its X-ray and ultraviolet cameras, gathering simultaneous images and videos of the dayside magnetopause, the polar cusps, and the auroral oval. SMILE will also host an ion analyzer and a magnetometer to monitor the ions in the solar wind, magnetosheath and magnetosphere while detecting changes in the local magnetic field.

The Electrojet Zeeman Imaging Explorer (EZIE) mission, planned for launch in early Fall 2024, will address the topic of energy, mass, and momentum transport between the magnetosphere and ionosphere by obtaining remote observations of the structure of the electrojet currents in the ionosphere to help distinguish between multiple published hypotheses of the structure of the substorm current wedge originating in the magnetotail.

NASA’s Geospace Dynamic Constellation (GDC) mission, which is currently planned for launch no earlier than 2028, will lead to a better understanding of magnetosphere–ionosphere–thermosphere coupling. GDC will address crucial scientific questions pertaining to the dynamic processes active in Earth’s upper atmosphere; their local, regional, and global structure; and their role in driving and modifying magnetospheric activity. Leveraging a constellation of spacecraft to enable simultaneous multipoint observations, GDC will be the first mission to address these questions on a global scale. This investigation is central to understanding the basic physics and chemistry of the upper atmosphere and its interaction with Earth’s magnetosphere, but also will produce insights into space weather processes. GDC mission goals therefore fit very well under this scientific objective, and the timely development and launch of GDC is strongly supported.

Ground-Based Facilities

Ground-based observatories have been instrumental in making immense contributions to this PSG. On Earth’s dayside, Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN) radar stations have captured poleward-moving mesoscale flows that form after dayside reconnection. Ground-based magnetometers have also measured localized transients and activity indices. A combination of SuperDARN radars and ASIs have viewed related ionosphere flows and auroral forms as they propagate from the dayside across the polar cap and through the auroral oval. ASIs and incoherent scatter (IS) radars have captured the energy flux input from precipitating magnetospheric particles and estimated the related conductance, showing that meso-scale features contribute an important (sometimes the majority) fraction of the precipitating energy flux. These magnetospheric drivers have major impacts

on the ionosphere–thermosphere (IT) system (e.g., the neutral winds and neutral densities) and the ionosphere itself can influence the magnetosphere directly or via feedback mechanisms (e.g., conductance enhancements). IS radars also measure convection, field-aligned flows, altitudinal conductivity profiles, and energy deposition in three dimensions. The Active Magnetosphere and Planetary Electrodynamics Response Experiment (AMPERE) gives continuous observations of global field-aligned current systems.

From these and other disparate missions and programs, it is known that meso-scale phenomena are critical to the energy, mass, and momentum flow into, within, and out of the magnetosphere. It is known that meso-scale flux transfer events are important on Earth’s dayside for transporting magnetic flux from the dayside to the nightside. But details are still unknown.

Theory, Modeling, and Simulations

State-of-the-art models are just now achieving the meso-scale resolution required to address this science priority and are also working to couple different regions of geospace. Two-way coupled models are necessary to capture the important feedback effects that occur in a coupled system. In the patchwork model of models approach, the nightside transition region (6–12 RE) is typically treated as the overlap of ideal MHD in the stretched tail, which excludes drift kinetic physics, and an inner magnetosphere model, which assumes slow flow and equilibrated flux tubes. In other words, two incomplete models are combined with the hope to approximate the result of a self-consistent model. The lack of a self-consistent treatment of the transition region limits not only the ability to understand the coupling between the magnetotail and inner magnetosphere, but also a critical feedback loop spanning the magnetosphere, ionosphere, and thermosphere. The challenge of modeling the transition region is that this requires both highly resolved spatial scales over geospace timescales of several days and kinetic physics that goes beyond the typical ideal fluid treatments currently used. While the ideal fluid treatment is the simplest physical description typically used, capturing the role of mesoscale processes on the global geospace system in a model or two-way coupling of kinetic and fluid models has only become possible in the past decade and remains quite challenging. As an example, the self-consistent global modeling of mesoscale auroral forms, like auroral beads, pushes MHD-based geospace models to their highest resolution capabilities.

How Does the Current Research Activity Motivate the Goal?

To make progress in understanding these processes requires observations, either in situ or remote, that capture phenomena occurring nearly simultaneously throughout the magnetosphere as well as coupled models with high enough resolution to capture the dynamic evolution of the magnetosphere. Past and current missions have provided insight to the benefits and progress that can be made when coordinated, multispacecraft missions are designed to address a specific open question. It goes without saying, however, that the magnetosphere is very large and very wide. To constrain the particle and energy transport mechanism through the transition region, for example, requires a 2D view in both azimuth and radial distance. The magnetospheric community has been creative in using the HSO to study events in an ad hoc way when satellite orbits and ground-based observatories align by chance. However, fortuitous conjunctions are limited in scope and frequency, making it difficult to fully understand how particles and energy are transported without a planned program.

In terms of modeling, approaches aimed at advancing beyond ideal MHD, including global Hall MHD, embedded particle-in-cell (PIC), global hybrid, Vlasov and multifluid-Maxwell, impose enormous computational costs currently forcing trade-offs like reduced dimensionality, resolution degradation or limited duration. For example, a recent 3D global magnetosphere hybrid-Vlasov simulation required 15 million core hours per 25 minutes of model time.

The current research activity motivates this PSG by revealing the importance of understanding the coupled magnetosphere system. Capturing and understanding the transfer of energy, mass, and momentum at scales smaller than global from the solar wind, throughout the magnetosphere, and into the ionosphere has to date been left to serendipitous conjunctions between disparate satellite missions and ground-based programs that have limited the ability to understand the system as a whole. Improving on the current activity requires a system observatory infrastructure with better coordination to go after the most pressing science objectives. Addressing the goal requires

coordinated observations and modeling with detailed physics (beyond ideal MHD, e.g., including the Hall term and kinetic physics) with spatial resolution capable of fully simulating meso-scale structures over typical geospace timescales. (See Table C-2.) The focus of these observations and modeling needs to be of the “transition regions” within geospace—that is, the dayside where solar wind impinges on the magnetosphere, the magnetic field transition region between the magnetotail plasma sheet and the inner magnetosphere (including the radiation belts and ring current), and the connection between the magnetosphere and ionosphere.

C.2.2 Priority Science Goal 2: What Are the Characteristics, Life Cycle, and Magnetospheric Impact of Plasma of Ionospheric Origin—Both the Cold Populations and the Hotter Energetic Outflows?

There are two sources of near-Earth plasma: the external source from the Sun, including the solar wind and solar energetic particles, and the internal source provided by the planet’s atmosphere. Modeling and observations have shown that both sources play a role, with the ionosphere becoming more important during active times, but there are still many questions regarding where and when the different sources dominate, and what their pathways are through the magnetosphere. Accurate identification of the source of the protons, the dominant species in the magnetosphere, is challenging because protons are the primary constituents of both the solar wind and the high-altitude ionospheric plasma. However, the two sources differ in both their energy distribution and their composition, and these can be used to infer the source. While the solar wind plasma is on average 96 percent H+, the ionospheric plasma that escapes into the magnetosphere can have a significant fraction of singly charged heavy ions, predominantly O+ and N+. Tracking singly charged heavy ions can provide insights into the dynamic linkage between the ionosphere and solar wind, as well as clues regarding the generalized ionospheric outflow and its role in affecting the ionosphere–magnetosphere system. While both the solar wind and the ionospheric plasma can contribute to the hot (>0.5 keV) plasma, plasma from the ionospheric source can also be cold. Tracking this cold population also provides information on the ionospheric source, including its acceleration and transport throughout the magnetosphere.

Owing to the cross-scale, cross-regime, and cross-energy nature of the circulation and energization processes affecting plasma of ionospheric origin, and because of the challenges in measuring the lowest-energy (<eV) ions and electrons, this plasma life cycle remains poorly understood. Determining the physical processes acting in distinct regions along the transport paths of the ionospheric ions will enhance the overall understanding of the characteristics, and lifecycle of the plasma of ionospheric origin, and reveal the impacts on the global magnetosphere dynamics. Specific objectives related to PSG 2 are given in Table C-4.

The plasmasphere is a vast reservoir of cold (~<1 eV) plasma in the inner magnetosphere with densities that can be more than 1,000 cm–3, orders of magnitude larger than densities for particles at higher energies. The source of cold plasma is primarily direct outflow from the ionosphere, with some contribution from charge exchange of more energetic ions with the neutral hydrogen geocorona. Plasmaspheric density and composition can play critical roles in wave generation and propagation, WPIs, and energetic particle scattering, and so the dynamics of this population affects many other aspects of the magnetospheric system. There are still many unknowns regarding the physics of plasmaspheric erosion and refilling. There are still fundamental questions regarding the physics that controls the outflow at the field line footpoint, and how the outflowing particles become trapped. Theoretical and modeling efforts demonstrate difficulty in explaining the observed refilling rates, which can vary from a few to hundreds of particles per cubic centimeter per day.

TABLE C-4 Objectives for Priority Science Goal 2

| Priority Science Goal (2 of 4) | Objectives |

|---|---|

| What are the characteristics, life cycle, and magnetospheric impact of plasma of ionospheric origin—both the cold populations and hotter energetic outflows? |

2.a. Determine how the plasmasphere forms and evolves. 2.b. Determine what drives ion outflow, and by what pathways the ionospheric-source plasma moves throughout the magnetosphere. 2.c. Determine the impacts of ionospheric plasma on the magnetosphere. 2.d. Determine the ultimate fate of ionospheric-source plasma. |

While light ion (H+ and He+) outflows, including those that form the plasmasphere, can be primarily explained by classical polar wind theory, the more energetic outflows observed in the auroral zone, including the outflow of heavy ion species (N+, O+, and molecular species NO+, N2+, and O2+), are more complicated because they require additional energy to overcome Earth’s gravitational potential. Several mechanisms have been identified that can combine to accelerate the ions including: upwelling from low-altitude frictional heating, heating of ionospheric electrons by soft electron precipitation, enhancement of the ambipolar electric field, transverse heating of ions through WPIs, ponderomotive forces of Alfvén waves or field aligned currents (FACs) driving the parallel electric field, and centrifugal acceleration owing to field line convection and curvature changes. These resulting ionospheric outflows can be either transported into different regions of the magnetosphere (e.g., plasma sheet and tail lobes) or can be lost to space on polar field lines connected to the interplanetary magnetic field. In situ observations have revealed the presence of ionospheric plasma throughout the magnetosphere, extending more than 200 RE down the tail. Still, many questions remain on the interplay of the heating and acceleration processes at different altitudes responsible for transporting heavy ions throughout the magnetosphere.

How heavy ions impact magnetospheric dynamics remains an active research topic. It is still uncertain whether heavy ions facilitate or inhibit the occurrence of substorms in the magnetotail, and how they impact the unloading during tail reconnection. Recent observations show that cold and heavy ions can slow the local dayside reconnection rate, but how much global dynamics are impacted is not known. The cold ions and electrons in the inner magnetosphere can change wave properties and energy transfer via WPIs in multiple ways, but the lack of cold ion and electron distribution functions, as well as cold ion composition measurements, has made detailed comparisons between observations and theory difficult.

The study of the escape of ionospheric ions has a broader impact, as well. Leveraging the understanding of charged particle acceleration, heating, transport, and circulation throughout the terrestrial environment, can provide clues about atmospheric loss at geological scales, and can aid in identifying the characteristic attributes of planet-star pairs that support habitability. Several mechanisms have been invoked to explain planetary atmospheric loss. For present-day Earth, thermal escape of neutrals is limited to only the lightest elements like hydrogen and helium. However, oxygen and other heavy species can escape into interplanetary space as ions after gaining sufficient energy to overcome the gravitational potential. Therefore, ionospheric outflow provides a pathway for atmospheric migration and escape at a rate that generally depends on the solar wind interaction with the planetary magnetic field. Notably, this process occurs without necessitating direct interaction with the solar wind.

Current Research Activity

Operating and Past U.S. and International Missions

Over the past decade, growing evidence has supported the hypothesis that cold plasma populations in the magnetosphere play a pivotal role in driving the system’s dynamics, highlighting the need to understand the sources of cold plasma in the near-Earth region, their pathways and impacts. Several missions, both recent (e.g., Van Allen Probes, TWINS) and historical (e.g., the Imager for Magnetopause-to-Aurora Global Exploration [IMAGE] mission, Polar) have contributed to the current knowledge of the various processes and components making up this system. However, in situ measurements of the cold (~1 eV) plasma are difficult to make; a positive spacecraft potential often prevents these ions from reaching the spacecraft, while negative spacecraft potential and/or photo-electron contamination can complicate cold electron measurements. The last instrument dedicated to measuring the composition of cold ions was carried on Dynamics Explorer 1 (DE-1), which included an aperture bias to overcome the spacecraft potential. Cluster also carried a plasma instrument with a low energy mode to measure the higher-energy tail of the plasmasphere particle distribution. Similarly, Van Allen Probes measured down to 1 eV. While the density calculated by Van Allen Probes using the lowest energy measurements does approximately track the plasmaspheric density, it is about a factor of 40 lower.

To capture the full plasma population, indirect measurement techniques are often used. The spacecraft potential or the upper hybrid resonance frequency are used to estimate the total plasma density but give no information on composition or energy and angular distribution. The IMAGE mission measured the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) distribution of He+, thus revealing the entirety of the plasmasphere and providing insight into the global structure

and evolution of the plasmasphere and its mesoscale features, such as plasmaspheric plumes, shoulders, and notches. However, determining the full density from these images requires assumptions about the composition. Ground- and space-based measurements of field line resonances have been used to determine the mass density distribution of the plasmasphere statistically; these can be combined with measurements of the total density from the spacecraft potential or upper hybrid line to determine the average mass. Still, there is much that has not been measured, even for the plasmasphere, the densest of the cold plasma populations.

The plasmasphere is not the only location where a hidden cold population may be present. The Cluster spacecraft identified a cold ion population in the lobe region using measurements of a perturbation in the electric field measurement owing to a wake caused by cold plasma flow around the spacecraft. In the magnetotail, another cold ion population was identified when a spacecraft charged negatively while in eclipse. Similar cold ion populations have also been observed during eclipses on geosynchronous spacecraft. The importance of these cold populations outside the plasmasphere are only now starting to be explored.

Hotter ionospheric plasma is easier to measure–instruments on Fast Auroral SnapshoT (FAST), Cluster, Polar, Van Allen Probes and MMS all measure ions from ~10 eV to ~40 keV with moderate mass resolution. All are able to distinguish H+, He+ and the CNO group. The combination of FAST measurements of outflow at ~4,000 km altitude, Cluster measurements over the polar cap and into the lobe and plasma sheet, MMS measurements in the equatorial plasma sheet and Van Allen Probes in the inner magnetosphere has provided an extensive database of ion measurements for statistically tracking the transport paths of ions through the magnetosphere. In addition, ENA imaging from both IMAGE and TWINS have provided a global perspective on the evolution of ions in the inner magnetosphere during storms, including differences in H+ and O+ behavior.

There are fewer measurements available for determining the processes that affect outflow at different altitudes and latitudes. Measurements from FAST, Akebono, Polar, and Cluster, have provided insights into various facets of ion outflow across distinct altitudes, albeit usually not concurrently. Sounding rockets have made substantial contributions to the current understanding of ion heating occurring at lower altitudes and the physical processes driving ionospheric outflow. For instance, the Sounding of the Cleft Ion Fountain Energization Region (SCIFER) experiment probed the origins of the Cleft Ion Fountain at altitudes of ~1,000–2,000 km, while the Magnetosphere–Ionosphere Coupling in the Alfvén Resonator (MICA) sounding rocket observed particle distributions below 325 km that constitute the primary source of the ion outflow. Other rocket experiments, such as Visualizing Ion Outflow via Neutral Atom Sensing (VISIONS-1, -2, and -3), have provided insight into the possible mechanisms responsible for the cusp ion outflow via ENA imaging and in situ particle measurements. These platforms can probe lower altitudes in complement to spacecraft observations. However, the measurements necessary to both identify the heating mechanisms that bring ionospheric ions above the exobase and illuminate the altitude dependence of acceleration that brings the more energetic ions into the magnetosphere are missing.

Ground-Based Facilities

Ground-based facilities play a crucial role in tracking plasma of ionospheric origin. IS radars are particularly effective ground-based tools for profiling the ionosphere from the D-region to the exobase and provide high-resolution measurements of quantities fundamental for specifying low-altitude boundary conditions for spacecraft measurements and mass extraction models. Existing IS radar facilities operate in the auroral zone (i.e., Poker Flat), in the cusp/cleft and polar cap boundary zones (i.e., Svalbard), and in the polar cap (i.e., Resolute Bay).

Altitude profiles provided by IS radar measurements can be used to derive parameters that are not possible through single-point measurements. By employing smooth curve fittings to these IS radar altitude profiles, it becomes possible to evaluate quantities that require derivatives or integrals of the plasma state parameters, like the ambipolar electric field, the divergence of the upflow number flux, the ion pressure gradient, and electron heat flux associated with thermal conduction. Smooth curve fittings applied to topside profiles enable the extrapolation of IS radar-derived profiles to spacecraft altitudes. Comparisons of these extrapolated values to the in situ measurements can then be used to infer the nature of additional acceleration occurring in the intermediate region between the highest IS radar measurements and the spacecraft positioned at higher altitudes.

Additionally, IS radar data can be used to quantify Joule heating and discern its altitude distribution by measuring the Hall and Pedersen conductivities alongside electric fields. Specifying the height distribution of these quantities is relevant to ion outflow science because heat deposited at higher altitudes is more effective at producing F-region upflows. IS radar altitude profiles of the E-region electron density enhancements are useful for estimating the characteristic energy and energy flux of the precipitating electrons. E-region density measurements are instrumental in quantifying the effects of upward field-aligned currents on the generation of outflow.

Beyond the insights garnered from IS radar data, including ground-based measurements derived from magnetometer chains and comprehensive total electron content (TEC) maps provides valuable information regarding the properties and evolution of Earth’s plasmasphere. One prominent technique employed in this context is field line resonance, which uses ground-based magnetometer data to infer plasma densities within the magnetosphere. A key factor influencing the accuracy and efficacy of this technique is the density of the ground-based magnetometer networks. Generally, a denser network enhances the reliability and precision of employing field line resonance as an investigative tool. Furthermore, measurements derived from magnetometer chains at different longitudes could constrain the longitudinal plasma mass density.

Last, Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) TEC measurements have proven invaluable in delineating the extent and evolution of plasmaspheric plumes. These measurements serve as a complementary resource to in situ observations of cold plasma density.

Theory, Modeling, and Simulations

The past decade marked the departure from the fluid description of ionospheric outflow and the development of novel hybrid approaches. Several numerical models have been developed to transition from a hydrodynamic to a kinetic formalism to include kinetic effects such as WPI. Resonant WPI provides new pathways for ion heating and acceleration, both in the cusp and auroral region, as cyclotron resonance with observed electric field fluctuations leads to the formation of ion conics, features frequently observed above the cusp and auroral regions. However, the wave heating is parameterized based on empirically derived formulas, which include significant uncertainty in the exact altitude profile of the wave power, and temporal variation is not accounted for. Moreover, the wave heating parameter is not dependent on the magnetospheric input, which is an imperfect estimate, but the most accurate one available at present.

A variety of methods including multifluid MHD, individual test particle tracing in MHD fields, and most recently global hybrid codes have been used to model the ion transport from the outflow region through the lobes, into the plasma sheet and into the ring current. There are pros and cons to each method. While significant results showing the impact of O+ on the global dynamics have been obtained using multifluid approaches, adequately capturing the velocity separation of the outflow population that occurs in the lobes and the nonadiabatic behavior, particularly for O+, in the magnetotail requires a kinetic approach (beyond the fluid approximation). Increases in computing power are finally making this possible.

Over the past decade, tremendous progress has been made in developing complex frameworks that allow for the exchange of information between global magnetosphere models and those focused on specific regions, such as the polar wind, plasmasphere, ionospheric electrodynamics, and inner magnetosphere. These frameworks enable self-consistent coupling between the plasma and electromagnetic fields and involve different levels of sophistication in modeling collisionless plasma dynamics, ranging from ideal MHD to fully electromagnetic kinetic plasma models (PIC or Maxwell-Vlasov). While these recent developments have been remarkably successful in simulating complex plasma phenomena—such as geomagnetic storms and substorms—and have advanced the knowledge of the effect of ionospheric plasma on the magnetosphere, they still have significant limitations.

The limited cold plasma observations force global magnetosphere models to rely on approximations, assumptions, and empirical relationships for boundary conditions. Therefore, many global and regional numerical models operate on the gross assumption that the ionospheric plasma density is either constant or empirically prescribed and do not include the contribution of heavy ions to the plasma.

Although there are global magnetosphere models that include a cold, dense plasmasphere population or a hotter ring current population, most existing models do not incorporate both the hot and cold populations together

in a self-consistent manner. This is a major issue because the plasmasphere holds most of the ionized mass and inertia in the magnetosphere, while the ring current carries most of the energy density. However, observations of cold ions and electrons in the magnetosphere are sparse, in contrast to the more energetic particle populations frequently observed. As a result, progress in developing models for the low energy particle populations has been slow. A functional understanding of plasmaspheric refilling requires, for example, coordinated observations of ionospheric and magnetospheric conditions and significant advancements in numerical modeling.

Understanding the characteristics, lifecycle, and magnetospheric impact of low-energy plasma will advance the understanding of the complexity, coupling, feedback, and inherent nonlinearity of the magnetosphere–ionosphere system. This endeavor requires advances in measuring the neutral density, plasma composition and distribution functions, and simultaneous observations of the magnetospheric energy inputs, to better constrain ongoing modeling efforts.

How Does the Current Research Activity Motivate the Goal?

Recent advancements in modeling and observations have provided us with a better understanding of the various components involved in the circulation of ionospheric plasma through the ionosphere–magnetosphere system. However, there is still a crucial need to link the parts together. In addition to measuring the ionospheric outflow, it is vital to track this plasma as it convects and circulates through the system. These developments have highlighted the benefits of utilizing both heterogeneous and multipoint measurements. For instance, obtaining a global view of the plasmasphere along with simultaneous in situ measurements will constrain plasma density and composition estimates. Additionally, measuring at multiple altitudes can help distinguish between ion upflow and outflow.

C.2.3 Priority Science Goal 3: What Controls the Multiscale Electrodynamic Coupling Between the Ionosphere and the Magnetosphere?

Magnetosphere–ionosphere (M-I) coupling lies at the intersection of many of the science questions important to the understanding of the magnetosphere system, including processes that regulate the transfer of energy from the solar wind to the magnetosphere and processes that regulate ionospheric upflow and ultimately outflow into the magnetosphere. Comprehensive space- and ground-based measurements conducted at Earth have significantly advanced the understanding of the M-I coupling system, and the results have been applied to other planetary M-I systems, as well. Despite those advances, there is an urgent need to expand both observational and modeling capabilities to capture mesoscale (~100–500 km in the ionosphere) processes at sufficient temporal scale ((1-minute cadence) and specify critical physical parameters, such as neutral winds and ionospheric conductance. New results are challenging long-standing assumptions used in modeling and the interpretation of observations including that the ionosphere is a thin-conducting shell, that the northern hemisphere ionosphere is a mirror image of the southern, and that M-I coupling processes can be treated with a quasi-static approximation. While these assumptions have worked well in laying the foundations for understanding of M-I coupling and the development of global models, more sophisticated modeling and comprehensive observational capabilities are needed to move beyond them to account for the dynamic, multiscale processes that play key roles in connecting the ionosphere to the magnetosphere, including during geomagnetic storms.

The overarching science goal can be divided into the four objectives, given in Table C-5.

Current Research Activity

Missions and Facilities Addressing This Goal

While there are no currently flying NASA missions devoted to studying M-I coupling, there are several currently in development that will make significant contributions to addressing part of this priority goal. First, the multisatellite GDC mission would provide unprecedented multiscale I-T measurements and has the appropriate instrumentation to determine the energy deposition and response of the I-T system to energy input from the

TABLE C-5 Objectives for Priority Science Goal 3

| Priority Science Goal (3 of 4) | Objectives |

|---|---|

| What controls the multiscale electrodynamic coupling between the ionosphere and the magnetosphere? |

3.a. Determine the response of the ionosphere/thermosphere system to magnetospheric and solar wind input as a function of altitude, latitude, and magnetic local time, including asymmetries. 3.b. Determine how the state of the ionosphere affects magnetosphere–ionosphere coupling. 3.c. Determine the physical processes controlling the structure and intensity of the global multiscale field-aligned current system. 3.d. Determine the drivers of the different auroral forms and airglow. |

magnetosphere. This strategic Living With a Star (LWS) mission was recommended in the 2013 solar and space physics decadal survey (NRC 2013; hereafter the “2013 decadal survey”) and the subsequent midterm assessment, Progress Toward Implementation of the 2013 Decadal Survey for Solar and Space Physics: A Midterm Assessment (NASEM 2020), and a pressing need remains for these measurements. This need is even more urgent with the possible decommissioning of the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) satellites in the coming years and expected lack of subsequent energy deposition measurements needed to study M-I coupling. Second, the Electrojet Zeeman Imaging Explorer (EZIE), a SmallSat mission consisting of three satellites in low-Earth orbit (LEO), will provide auroral electrojet measurements using a remote sensing method to probe the poorly sampled ionospheric region where these currents are flowing. By examining electrojet dynamics in this region and under different driving conditions, EZIE will provide new insights into the electrodynamic coupling between the ionosphere and magnetosphere.

There are several other primarily National Science Foundation (NSF)-supported projects with objectives and corresponding measurements that relate to M-I coupling. Most of these projects involve ground-based measurements. Briefly, they include (1) SuperDARN radars that provide multiscale ionospheric flow measurements at 1- to 2-minute cadence, (2) IS radar measurements that provide comprehensive regional ionospheric plasma measurements, and (3) Iridium satellite magnetometer measurements that are used to determine global field-aligned current patterns (AMPERE) at ~10-minute cadence. Alongside these larger projects, there exist many other smaller principal investigator–led projects with a wide range of instrumentation and objectives, including projects involving ground-based magnetometers, ASIs, riometers, and so on. Although these projects provide the observations needed to address this science question, the more coordinated effort described below is needed to fill gaps in instrumentation and spatial coverage to make significant progress. Last, the NSF-supported Madrigal and SuperMAG databases provide essential tools needed to aggregate and access data sets with often widely varying formats.

International collaborations have provided key measurements needed to address this science question. Significant contributions have been made by the ESA Swarm mission and are likely to be made by the upcoming SMILE mission, which will use a combination of imagers and in situ measurements to explore how solar wind driving conditions affect the magnetosphere and high-latitude ionosphere. Ground-based magnetometers and ASIs operated through support from the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) have been essential in providing measurements needed to explore a wide range of M-I coupling processes. The new EISCAT 3D radars will provide unique volumetric measurements needed to probe M-I coupling in 3D. Last, international collaborations are providing key logistical support needed to access high-latitude southern hemisphere regions in Antarctica that are required to examine inter-hemispheric asymmetries; this is likely to become even more important in the next 10 years owing to expected reductions in logistical support by the U.S. Antarctic Program.

Quantifying the energy flow between the solar wind/magnetosphere and the I-T system is essential for holistically understanding energy flow across different geospace regions. This requires measurements of particle precipitation and electromagnetic energy input as a function of altitude, latitude, and magnetic local time (MLT) in both hemispheres. Currently, the DMSP satellites provide limited measurements of precipitating particle energy and Poynting flux into the I-T system at fixed local times, as well as the far ultraviolet (FUV) images of high-latitude regions needed to image the auroral zone from space. It is important to note that these satellites are expected to be decommissioned in the next few years, which will greatly impede efforts to quantify energy deposition. Sounding rocket and balloon investigations have also provided detailed single- and multipoint measurements of

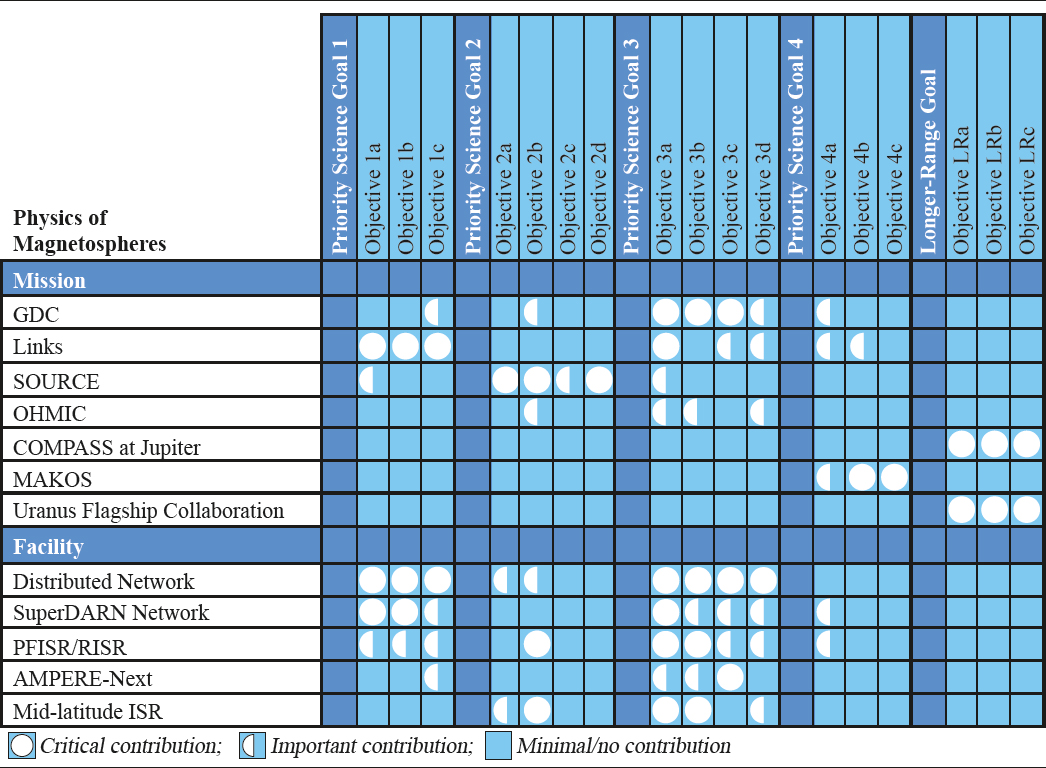

these parameters. However, there are no global-scale measurements of these energy flows, which are critically needed as high-latitude drivers of global I-T models. Assuming that Joule heating in the ionosphere equals the input energy, Joule heating and, thus, conductance and convection electric field have often been calculated to estimate the input energy by ignoring neutral winds. However, the lack of global specification of both conductivity and neutral wind distributions at any timescale have introduced considerable uncertainties in quantifying the energy deposition into the I-T system and its response. In terms of the I-T response to energy input from above, there has been a lot of progress on how the ionosphere plasma content, such as the TEC, changes during storms and substorms, mainly owing to the rapidly increasing number of ground-based GNSS receivers, GNSS constellations, and conjunctions with complementary measurements, such as from IS radars and LEO satellites. In addition, understanding of the low and mid-latitude ionosphere and thermosphere responses to energy input during geomagnetic disturbances has been significantly improved by multiple recent missions, including Ionospheric Connection Explorer (ICON), Global-scale Observations of the Limb and Disk (GOLD), and Constellation Observing System for Meteorology Ionosphere and Climate 2 (COSMIC-2). However, progress in understanding I-T responses to external energy input at high latitudes is very limited.