Framework and Tools for Incorporating Technologies into Airport In-Terminal Concessions Programs (2025)

Chapter: 4 Domain Areas to Consider for Successful Program Implementation

CHAPTER 4

Domain Areas to Consider for Successful Program Implementation

This chapter focuses on addressing the domain areas that airports should consider as key elements in establishing or improving existing concessions technology programs or initiatives, as applicable. Topics include strategic business alignment, model agreements for concessions contracting, stakeholder collaboration, human workforce, passenger buying habits, information technology (IT) system architecture and infrastructure, data governance, budget, business value proposition/return on investment (ROI), and performance and success measures.

4.1 Organizational Culture and Alignment with the Mission/Vision/Values

To ensure program success in an airport concessions technology program, it is particularly important to have strong alignment of an airport’s mission, vision, values and organizational culture. Establishing such alignment will ensure enterprise-wide support of airport management for the program.

4.1.1 Mission and Vision

- The mission defines the airport’s core purpose and focuses on passenger experience, safety, efficiency, and revenue generation.

- The vision describes the airport’s desired future state and emphasizes its technological leadership and commitment to innovation and to further enhancing the customer experience.

- Shared values are fundamental beliefs, concepts, and principles that underlie the culture of an airport. Values that resonate with Generation X, millennials, and Generation Y can be the key to the successful recruitment and retention of younger generations within the workforce.

4.1.2 Organizational Culture

In addition to shared values, organizational culture includes the attitudes and behaviors that shape how airport employees work together. When an airport concessions technology program has aligned its mission, vision, and organizational culture, airport workers are more likely to do the following:

- Embrace technology. View technology as a tool for achieving the mission and vision rather than as a burden. In addition to helping make an airport employee’s job easier, technology can also support the transition of airport employees into jobs that require more skill and more pay.

- Be innovative. Be encouraged to find new technological solutions that improve passenger experience and generate revenue.

- Collaborate. Work effectively with concessionaires and technology providers to implement and integrate new systems.

Airports can utilize the following techniques to assess and strengthen the alignment:

- Review mission and vision statements. Ensure that they are clear, concise, and reflect the importance of technology in achieving delightful customer experiences within the desired future state.

- Evaluate current culture. Conduct surveys or hold focus groups to understand employee attitudes toward technology and innovation.

- Identify gaps. See how the current culture aligns with the vision and mission. Are there any cultural barriers hindering technology adoption?

- Develop strategies. Implement initiatives that bridge the gaps. This could involve training programs; communication campaigns using diverse social media channels and virtual job fairs that appeal to Generation X, millennials, and Generation Z; attracting staff through internships; focusing on educational pathways and clear career pathways; or even hiring practices that prioritize tech-savvy individuals.

- Enhance the airport’s employer brand and competitiveness as an employer. Airports should create a positive employee experience and should address some of the challenges that airport employees face.

As a result of this alignment of mission, vision, and values, airport concessions technology programs will be more successful in enhancing an organizational culture that values innovation and collaboration and fosters smoother technology adoption by concessionaires. Additionally, better alignment will improve passenger experience by utilizing technology to streamline existing processes, personalizing offerings, and enhancing passenger satisfaction.

The research team identified several strategies that airports can use to achieve alignment with airport concessions technology programs (Figure 5). These strategies are as follows:

- Leadership commitment. Obtain senior management’s support, because they are the ones who champion the mission, vision, values, and technology integration and set the tone for the organization.

- Clear communication. Clearly communicate the mission, vision, and values and their link to the planned concessions technology programs.

- Training and incentives. Invest in training and incentivize airport workers to embrace new technologies.

- Collaboration. Foster collaboration among airport staff, concessionaires, and technology providers and any other external stakeholders as required.

- Change management. Develop a change management plan to address resistance and ensure a smooth transition for staff affected by the insertion of new technology in the concessions program.

- Security focus. Integrate data security awareness into the organizational culture.

- Establishment of an innovation program. Develop an airport innovation program that can assist airport workers to think outside the box and ideate on behalf of the betterment of the airport organization. It should be noted that many airports now have chief innovation officers or innovation program directors leading the charge to get every single airport worker to be innovative. These programs often use incentives and rewards to benefit airport workers who contribute to innovation.

In summary, by fostering a culture that aligns with the airport’s mission, vision, and values, airports can leverage technology programs to enhance the passenger experience, streamline operations, and generate more revenue within the airport concessions space.

4.2 Considerations for Concessions Contracting Models

Certain management methodology approaches are believed to be more conducive to employing concessions-related technologies than others (Airports Council International 2022). All U.S. airports, except Raleigh–Durham International Airport (RDU) and two other small airports, use one of seven common concessions management methodologies (Figure 6). Additionally, some airports use multiple methodologies (hybrids). The choice of the right management methodology is key to the success of an airport’s concessions program. The right methodology is unique to an airport and its situation at the time of the decision.

4.2.1 Concessions Contracting Models

Direct Leasing

Under this management model, an airport leases all its concessions space, usually in groups of one to three stores per package. An airport operating under this model has the most control over its concessions program, but implementing the model successfully also requires significantly more effort than any other management methodology on the part of airport staff. The airport can also target the type of program it wishes to have and focus on local operators and well-known local and regional brands if desired. Implementing this approach requires more

concessions-focused staff with significant specialized knowledge of leasing and store/mall management. San Francisco International Airport (SFO) and Portland International Airport (PDX) are recognized as leaders in this approach.

Master Concessionaire

This approach is likely the easiest management model for an airport to administer. The airport only has to manage one concessionaire contract, or one contract per concession type (i.e., one food and beverage concessionaire and one retail concessionaire). This model became less popular in the late 1980s as airports began to see the value of competition in an airport concessions program. The only remaining large airport that continues to utilize this model is Charlotte Douglas International Airport (CLT), which has had contracts with HMSHost for food and Paradies Lagardère for retail for decades. Fort Lauderdale–Hollywood International Airport (FLL) uses a variation of this model. The airport has four terminals. HMSHost operates the food in two terminals and Hudson operates the retail. In the other two terminals, Delaware North operates the food and Paradies Lagardère the retail.

Multiple Prime Operators/Packages

Airports that use this approach offer multiple packages of locations, usually consisting of three to 10 units, depending on the overall program size. Some airports have offered small packages of one or two units to create smaller opportunities that are more appropriate for either nonairport contractors who have never been able to succeed in competition with the large national vendors or for airport-experienced vendors who might only have gained their experience as subcontractors (or joint venture partners) to a larger firm. Packages can be food only, retail only, or a combination of the two, because all major U.S. contractors can now propose mixed opportunities, either with their own operations experience or as a team with another operator. As with the master concessionaire model, the winners of larger packages will operate some locations themselves and either sublease or create joint ventures to operate other locations to meet the participation goals of the Airport Concessions Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (ACDBE) program. This is the most common airport concessions management model in the United States at this time. Three airports currently using this approach are Southwest Florida International Airport (RSW), Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport (MSP), and San Diego International Airport (SAN).

Developer

In this management model, all concessions spaces are leased to the developer, who then directly leases them to operators for single or multiple locations. When the developer model was introduced, the developer would lease individual locations or small packages (two or three units) to independent operators, often local and frequently ACDBE certified. Programs under this traditional model, such as Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT) and Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI), run by Fraport and its predecessor companies BAA USA and AirMall USA, and Boston Logan International Airport (BOS), with Fraport and URW Airports each responsible for two terminals, are well-respected in the industry for their diversity, which often reaches 50% or more ACDBE participation. PIT, BOS, and BWI acted very much like a regional mall. However, more recently, developers have acted as if they were leasing a prime concessionaire model, giving all of the food locations to one operator and all of the retail locations to another and then expecting these sublessees to sub-sublease or develop joint ventures to operate units that generate enough sales to meet airport ACDBE goals. These programs are less locally focused and bring in fewer small operators, although it is likely that the lessee will operate units where they have either licensed the brand or which are proprietary brands that are not local and do not exist outside of the airport but whose names sound local (e.g., “Best of Baltimore” or “Front Street Bar”). Fraport utilizes this model to manage Nashville

International Airport (BNA), and URW Airports uses it for Chicago O’Hare International Airport (ORD) Terminal 5.

Operator/Manager

Prime operators proposed this approach to respond to airports that had chosen the developer model. Rather than present a master concessionaire or packages methodology that the airport had likely already considered and rejected, they renamed the methodology the operator/manager model and presented it as being the same as the developer model. The major difference is that a developer cannot operate any locations, while under the operator/manager model, the selected company can be the operator, often up to a limit, such as a percentage of total concessions space or a number of units. The operator/manager must then sublease the remainder of the program to third-party operators, with joint ventures between the operator/manager and the small operators permitted and thus featured prominently. If all remaining spaces are subleased to entities not contractually related to the operator/manager, this is similar to the multiple primes/package methodology. If the independent operations are primarily joint ventures or subleases to affiliate companies, the operator/manager is, in effect, operating most or all of the program, turning it into a master concessionaire contract in disguise.

Airport Operator

The largest barrier to entry to airport concessions is the cost of participation in an airport program, followed closely by the lack of knowledge of how to do business in an airport environment. To address these issues and permit the airport a greater level of control over the concessions operations that are not available in any other management methodologies, a few airports are experimenting with an airport operator model. In this model, the airport is a joint venture partner with operators. This methodology is not uncommon outside the United States, especially in duty-free concessions, but has not been tried in the United States until now. The airport’s contributions to the joint venture include the concessions location, fit and finish (except for signage or unique trademarked signature decoration/signage), accounting services, banking services, and significant knowledge of how to do business in the specific market. The operator brings local brand awareness, operating knowledge, and unique trademarks or service marks to brand the concessions location.

The operator may also need to provide any unique cooking equipment that is particular to the brand’s operation. In this model, the operator runs the day-to-day business, is responsible for managing the staff, and makes a daily deposit of each day’s revenue into an account owned by the airport (less the operator’s fee) for this specific partnership (thus, two operations under this model require two bank accounts, three operations require three accounts, and so on). It is then the airport’s responsibility to do the daily and monthly books for the operation and prepare a monthly true-up to ensure that both parties receive the share of daily revenues that they expect. There is usually a profit-sharing clause in such contracts. Expenses (e.g., operator’s share, airport’s share, maintenance, labor) are covered. The airport has access to the point-of-sale system (because the airport provides it as part of the build-out), so it has access to levels of information about a concession’s operation that have been unavailable to airports.

Fee Manager

A fee manager supplies expertise and personnel as an extension of airport staff. Unlike the developer model, the leases in the fee manager model are between the airport and the concessionaire, not the developer/fee manager and the operating concessionaires. Fee manager responsibilities often include contract (lease) administration, lease compliance, and program management, thereby ensuring that concessionaires whose leases are held with the airport meet their contractual obligations and contribute to the customer experience. The fee manager may

develop and implement airport-wide promotions to increase sales at all concessions, usually utilizing a monthly marketing fee paid by the concessionaires. The fee manager may participate in space planning but generally does not make any investment in the airport or the concessions programs, except to build out and furnish its own offices. ORD uses this approach to manage the concessions program. When BOS last solicited management for the concessions program, it called it a fee manager but still required a significant investment, which made it, in actuality, a developer solution.

4.2.2 Management Methodologies and Technology

Certain management methodologies are better suited to facilitating the integration of technologies to enhance the throughput of concessions sales or improve the customer experience. At the heart of this analysis lies the airport’s ability to shape technology adoption directly, through investment decisions, or indirectly, through day-to-day management.

The initial concessions solicitation for proposals serves as the primary opportunity for an airport to express its desire or mandate for concessionaires to introduce technologies that enhance passenger experience and drive sales. During this phase, concessionaires factor in technology investment costs within their profit and loss statements, as these costs ultimately affect their ability to meet the rent requirements outlined in the solicitation.

However, airports may encounter challenges if they request concessionaires to invest in technologies midway through an existing agreement without adjusting other lease terms (e.g., rent or lease term). Therefore, during the solicitation process, it is crucial for airports to advocate for technology investments and ensure that lease agreements incorporate technological advancement provisions. Appleton International Airport’s (ATW’s) request for proposal (RFP), issued in January 2024, required the following from the proposers:

- Incorporate technology in a meaningful way that will enhance the passenger experience.

- Highlight the proposed technology to be used for the program to boost sales and enhance the passenger experience. The technology applied may be either front of house (e.g., self-check or remote ordering) or back of house (e.g., automated inventory management system, maintenance management system). Specify what technology will be introduced when the program launches.

- Provide any supporting information for technology that may be implemented to drive sales and create a differentiated customer experience, such as Just Walk Out, self-checkout, and self-ordering, along with any information regarding technology, such as point-of-sale equipment, video cameras/video management systems, or other innovative solutions that will enhance operations management.

Table 1 summarizes the ease with which an airport might employ concessions technologies related to each concessions management model.

Figure 7 provides a visual plot of the influence of technology implementation based on the management methodology employed by the airport. The figure indicates that the multiple prime, developer, or master concessionaire models are best suited for having concessionaires bring technological advancements to the airport market, as opposed to the direct leasing model, which is believed to have a higher probability of capital investments by the airport.

Table 2 identifies some of the more widely implemented concessions technologies and maps them against the management methodologies used in their programs. For the purposes of this discussion, the fee manager model and operator/manager model are excluded because (1) the fee manager model does not directly affect the deployment of technologies in concessions programs

Table 1. Concessions management models and technology deployment.

| Model | Entity Most Likely to Contribute to Technology | Primary Driver for Adding Technology | Primary Challenges for Adding Technology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct leasing | Airport | Airports can bring to their direct lessees preferred technologies and ask concessionaires for capital contributions as a first step before determining the level of investment required of the airport. | Challenging for concessionaires due to the awareness of technological advancements and costs. This is especially true for independent and local concessionaires that have not operated previously in the airport environment and that may have limited access to capital. Coordination of independent operators to participate in an airport-wide technology is challenging. |

| Master concessionaire | Concessionaire | The brand owner may have initiatives in place to add technologies for a competitive advantage during the RFP process. | Potential lack of motivation to invest due to a lack of competition by any other airport concessions lessee. |

| Multiple prime operators/packages | Concessionaire | Different corporations may have different plans in place to add different technologies for a competitive advantage. | Large portfolios of space managed by a prime operator may result in spreading out significant technology investment costs, although cloud-based technology is not sensitive to the number of units in the portfolio. |

| Developer | Developer and its sublessees (concessionaires) | Driving top-line sales is the primary motivation of a developer and is similar to the airport’s primary goal. Profit is not a priority for a developer. | While the developer may contribute to the investment, technology implementation still requires tenant cooperation and (likely) investment, in a manner similar to direct leasing. Coordination among individual sublessees is required for technologies that are common to all concessionaires. |

| Operator/manager | Concessionaire | Corporations may have initiatives in place to add technologies for a competitive advantage. This will also require investment by sublessees and joint venture partners who may lack capital. | Coordination among individual sublessees and the operator/manager’s own operations. Little influence over sublessees to employ technology unless the sublessee is also a joint venture partner. |

| Airport operator | Airport | The airport has control over the concessions operations. The airport can establish technologies to be employed and then managed by the brands. | The airport needs to be attuned to industry trends and what technologies will drive customer experience and sales. |

| Fee manager | Airport | Will follow the direction of the airport; does not establish policy but could influence the airport’s decisions with research and recommendations. | The airport is likely involved in project management/implementation. |

Table 2. Technologies and concessions management models.

| Concessions Management Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | Direct Leasing | Multiple Primes | Master Concessionaire | Developer | Airport Operator | Operator/Manager |

| Mobile preordering | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Delivery services (e.g., At Your Gate, Uber Eats) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Self-checkout (e.g., MishiPay, Just Walk Out, Hudson Non-Stop) | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Vending machine shop (e.g., 24/7) | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Contactless payment kiosks | X | X | X | X | X | X |

and (2) the operator/manager model is, as described above, essentially the same as the multiple primes model. It should be noted that the conclusion is that the specific technology deployed is not directly related to the management methodology in use.

4.3 Stakeholder Collaboration

Interviews with airport and nonairport executives highlighted the importance of collaboration in driving innovation. Designing and delivering excellent, efficient, and seamless customer experiences across all journey points in the airport environment is challenging. Although there are many service providers in the airport’s service delivery chain that are responsible for service excellence, from the customer’s point of view, the airport journey is experienced as a continuum. Although one service provider may be responsible for a service failure, the customers and the

media generally hold the entire airport accountable. This is why early and ongoing collaboration throughout each project’s life cycle is critical across the board, especially when it comes to the challenges associated with the successful implementation of emerging technologies within the airport ecosystem generally and the evolving landscape of airport concessions specifically. This reality presents an opportunity for airports to engage with technology providers, airlines, and concessionaires to cocreate solutions that address customer needs, empower airport employees, enhance the overall travel experience, and increase nonaeronautical revenues for the airport operator and its business partners.

4.3.1 Building Cross-Functional Teams for Technology Initiatives

Any major technology program at an airport requires strong cross-functional team collaboration. The introduction of a new technology may have an existing business process, staff roles and responsibilities, and direct and indirect impacts on airport stakeholders, both internal and external. Airport concessions technology programs may require inputs from a variety of business units, such as operations, IT, security, commercial management, and property management. In addition, airport tenants, both airline and nonairline, may be affected. Thus, from the onset of any project, it will be important to engage the right team members.

The key to building a cross-functional team is to ensure the inclusivity of all necessary parties on a project from the beginning. Everyone needs to understand the goal of the project and their level of involvement—expectations should be set and understood. Figure 8 illustrates the following strategies to get airport business units to collaborate with stakeholders on airport concessions technology programs:

-

Focus on shared goals and benefits:

- – Focus on the bigger picture. Frame the technology program as an improvement to the passenger experience that will lead to increased customer satisfaction and loyalty, which benefits everyone.

- – Employ a data-driven approach. Use data to demonstrate the potential benefits of the program. This could include increased revenue from concessions, improved efficiency in operations, or better passenger satisfaction ratings. Stakeholders need to understand what is in it for them and how they benefit from the program.

-

Address concerns and foster trust:

- – Start early. Identify and collaborate with stakeholders early in the process to incorporate their opinions into the program design.

- – Be transparent. Engage airport staff who will be affected by the project via focus groups or other forums on a regular basis. Clearly communicate the goals of the program, how the data will be used, and how the staff will be affected. Address privacy concerns proactively.

-

- – Use pilot programs. Start with a pilot program for a specific concessions area or technology to allow stakeholders to see the benefits firsthand before wider implementation.

- – Identify champions and leaders. Identify champions and leaders within each business unit who can advocate for the program, address concerns from colleagues, and participate in the implementation process throughout the life of the program.

- – Celebrate. Celebrate success and achievements across business units to strengthen engagement and enthusiasm for the program.

-

Establish a structure for collaboration:

- – Use a RACI matrix. Develop and distribute to all team members the project’s responsible, accountable, consulted, and informed (RACI) matrix, as it provides a clear structure for collaboration, communication, and accountability, which are all essential ingredients for a successful cross-functional team (Miranda and Watts 2024) (Table 3).

- – Create working groups. Establish working groups or committees that include representatives from different business units and stakeholder groups. This fosters information sharing and common interests.

-

Facilitate communication and decision-making:

- – Hold regular meetings. Schedule regular meetings to discuss progress, identify shortcomings, address challenges, consolidate learning, and make decisions collaboratively.

- – Employ a clear decision-making framework. Establish a clear process for making decisions about the technology program to ensure that everyone has a voice.

- – Set project milestones and key performance indicators (KPIs). Establish project milestones and KPIs to ensure that the cross-functional team is aligned regarding objectives and progress and objectively measure the success of the program and its components (Langat 2025).

-

Focus on training and support:

- – Provide training. Develop a transition or training program or both to fully upskill or reskill internal stakeholders.

- – Provide technical support. Offer ongoing technical support to address any issues that arise after implementation.

Following these strategies can create a more collaborative environment in which airport business units and stakeholders can work together to develop and implement successful airport concessions technology programs.

4.3.2 Workforce Element Considerations

Although technology can increase productivity and improve operational efficiency while also providing the opportunity to offer a more personalized experience for travelers, it needs to be supported by employees. Employees implement the technology, using it as part of their work

Table 3. Sample RACI matrix.

| Task | Responsible | Accountable | Consulted | Informed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Develop technology requirements | IT department | Project manager | Concessions team | All stakeholders |

| Select technology vendor | Project manager | Procurement team | IT department, concessions team | All stakeholders |

| Implement the technology | IT department | Project manager | Concessions team | All stakeholders |

| Train concessions staff | IT department | Concessions team lead | Concessions staff | All stakeholders |

| Monitor and evaluate program success | Project manager | All business units | All stakeholders | All stakeholders |

routines, and they also complement the technology by providing hands-on user assistance or serving as an alternative to the technology. As a result, it is important to consider the workforce implications of how and where technology is used.

Early Engagement of Airport Employees

Airport employees are extremely valuable airport assets for whom the implementation of technology can be frustrating and threatening. To ease the transition, the early engagement of the employees who will be affected should not be overlooked. Early and ongoing engagement leads to better solutions as well as energized employees who are ready to support the new way of delivering service to the airport’s customers. Engaged employees also lead to increased retention of knowledgeable staff with the diverse skills needed for future roles created by the implementation of technology.

Attracting and Motivating Generation Z and Beyond

In addition to employee engagement, the industry will also need to emphasize attracting and motivating Generation Z. As pointed out in “Evolution of Airports: Travel Trends in the Next 30 Years,” 85% of Generation Z favors remote or hybrid work settings, which poses a distinct challenge for airports, as many airport jobs require working onsite (Oliver Wyman Forum 2023). Airports will need to develop ways to attract, motivate, manage, and retain this workforce.

Collaboration with Academia

Collaboration with academia will also be needed to create interest in aviation, facilitate recruitment in sufficient numbers, and ensure that airport staff have the correct skills. Upskilling will be essential when it comes to digital and technical skill sets, as will the soft skills needed to undertake more humanized, customer-facing roles. Sensitive service recovery roles become important when technology fails or is misunderstood by the customer. Investing in ongoing training to enhance or refresh employee skills to make them future-proof and focusing on the employee experience at the airport as passionately as the airport pursues customer delight will lead to an increase in employee retention, which is a win-win scenario.

Take care of your employees, and they’ll take care of your customers.

— J. W. Marriott, Jr. (2017)

4.3.3 Identifying and Engaging Relevant External Stakeholders

Obtaining the engagement and support of relevant external stakeholders is a key program element in the adaptation of technology to an airport concessions program. External stakeholders are defined as those who are not part of the airport organization. Figure 9 shows some program strategies that can assist in the identification and engagement of external stakeholders with regard to the technology or application being deployed by the airport concessions program.

Following are several recommended best practices for successful engagement of external stakeholders:

- Engage external stakeholders early in the program. Doing so is very important to building trust and fostering a sense of ownership in the success of the program.

- Maintain open communication channels and keep stakeholders informed about project progress, challenges, and decisions.

- Be clear about the level of involvement expected from each stakeholder and manage their expectations throughout the project.

By following these steps, airports can better ensure a smooth rollout of their concessions technology program that maximizes its benefits and minimizes potential disruptions.

4.4 Passenger Buying Habits/Personas

Understanding passenger buying habits can help airports leverage which technologies are best suited to meet passengers’ needs. To do this, the research team analyzed the trends, patterns, and correlations in the Air Passenger Survey dataset (see Appendix B) and identified four high-level personas. These personas are not just fictional representations but are grounded in real data and survey research. They encompass various traits, such as demographic attributes, psychographic attributes, core motivations, pain points, and technographics and provide a comprehensive view of different traveler types.

4.4.1 Role and Impact of Personas in the Airport Ecosystem

Personas serve a critical role in contextualizing passenger journeys within the airport ecosystem. They allow for the mapping of unique passenger experiences and for catering to the distinct ways in which different customers interact with brands, services, and technology. This leads to more relevant and personalized experiences for travelers at scale. The use of personas simplifies design tasks and focuses on the varied needs of different customer groups. Personas unify teams around a common language and understanding of stakeholder groups, humanize market segment data, and build a deeper connection to stakeholders. This approach is pivotal in creating customer-centric experiences, guiding future research efforts, and aiding in decision-making.

4.4.2 Utilizing Personas for Enhanced Airport Experiences

While there is no limit to how many personas can be created, it is best to remain focused and targeted. Identifying the most important stakeholders (e.g., primary customers, employee

groups, purchase influencers) will help do this. At their core, personas are about painting a fuller picture of stakeholders to build a brand (or, in the case of airports, an ecosystem) and better design options and experiences. Knowing which characteristics influence customer perceptions and behaviors will help airports and concessionaires connect better with them. A primary objective of incorporating technology into an airport’s concessions program is to enhance the customer experience. To accomplish this goal, airports must first understand who their customers are and how they relate to technology.

4.4.3 Defining Key Traveler Personas for Technology and Concessions in Airports

In analyzing the responses from the Air Passenger Survey, the research team identified four distinct airport passenger personas, each representing unique interactions with and attitudes toward technology:

- The Tech-Savvy Young Explorer, who is a younger, technology-enthusiastic traveler;

- The Digitally Engaged Family Navigator, who leverages digital tools for efficient family travel;

- The Connected Business Professional, who relies heavily on technology for business travel efficiency; and

- The Golden Age Leisure Enthusiast, who is an older traveler who prefers a more traditional approach to travel and technology.

These personas, derived from comprehensive data analysis, offer valuable insights for airports and concessionaires seeking to understand and cater to the diverse technological needs and preferences of different traveler segments and create tailored and satisfying airport experiences. Figure 10 presents the four personas with their weighted response allocation.

Airports can use these personas when considering how technology is incorporated into their in-terminal concessions programs. Following are some key commonalities across the four personas:

- Convenience and efficiency—desire for streamlined travel experiences,

- Technology usage—reliance on digital tools for various travel-related tasks, and

- Real-time updates—importance of timely information on flight status and other services.

On the basis of the findings of the various passenger personas, the research team identified the following opportunities for airports to consider as they develop airport concessions technology programs:

- Communication and engagement. Improve strategies to ensure timely and relevant passenger information.

- Leveraging passenger feedback. Use insights to bridge gaps between passenger expectations and reality.

- Digital services in concessions. Enhance dining and shopping experiences with digital menus and contactless payments.

4.4.4 Travel Habits and Preferences

- Business travel continues to lag behind leisure travel in this post-pandemic era.

- Leisure travelers typically fly less frequently than business travelers and may, therefore, want more certainty and information during their journey. Technology can create this certainty.

- Respondents should have good familiarity with airports and with how the rigors of air travel can be improved with technology.

- Significant dwell times at the airport, as these data indicate, could be influenced by airport recommendations, the need for buffer time due to the uncertainty of getting to the airport and through airport security, or personal preferences. Long dwell times mean that discretionary times for food and retail purchases are significant and can be enhanced even further with the use of digitalization to assist in purchases.

- Passengers may want the certainty that, for example, the plane has arrived, the flight is leaving on time, and the time it takes to move from places of interest in the concourse (e.g., a restaurant brand they walked past) to the gate is X minutes. Flight information display system areas can be the hub for sharing information that passengers seek beyond just flight and gate status data.

4.4.5 Technology and Communication

- Passengers are adopting technology, want more of the information and efficiency that technology can provide and are equipped to access that information.

- While privacy and data security concerns may continue to grow, the general acceptance of technology may counter those concerns.

4.4.6 Spending at the Airport

- The reported spending levels from this survey are generally in alignment with passenger sales per enplanement reported in the industry, although on the low side. Airport surveys that capture spending via an intercept are generally more accurate than an Internet-based survey, which requires respondents to recollect something that may have occurred months ago.

- Use of contactless payment is likely to increase with time, either as a result of it being a preferred payment option or because of the ongoing staff resource issues that concessionaires face.

4.5 System Architecture Considerations

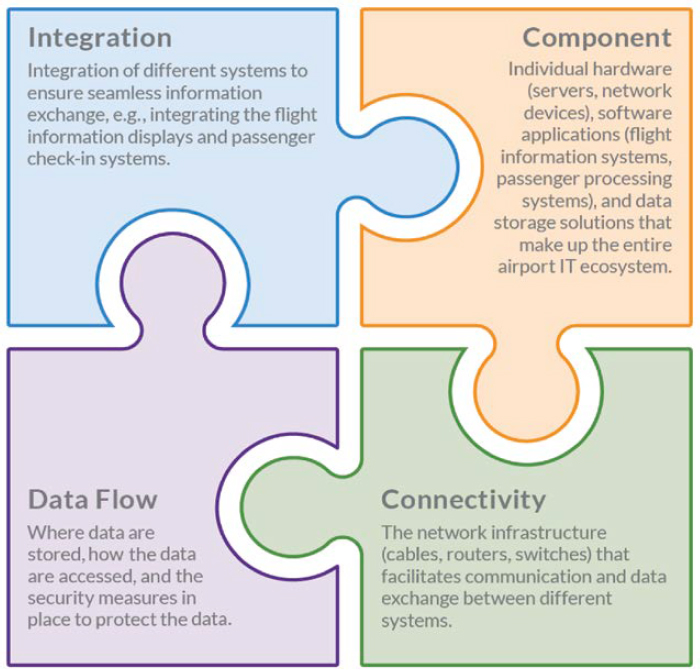

From the perspective of airport IT, system architecture is the blueprint that defines how various technology components work together to achieve the airport’s goals. It is essentially a roadmap that outlines the elements shown in Figure 11.

A well-defined system architecture is the foundation for successful digital transformation at airports. An airport concessions technology program can involve a complex interplay between different systems, either existing or new. As a result, it is important for an airport to ensure that it has a robust, flexible, scalable, and adaptable system architecture.

4.5.1 Considerations for Supporting an Airport Concessions Technology Program

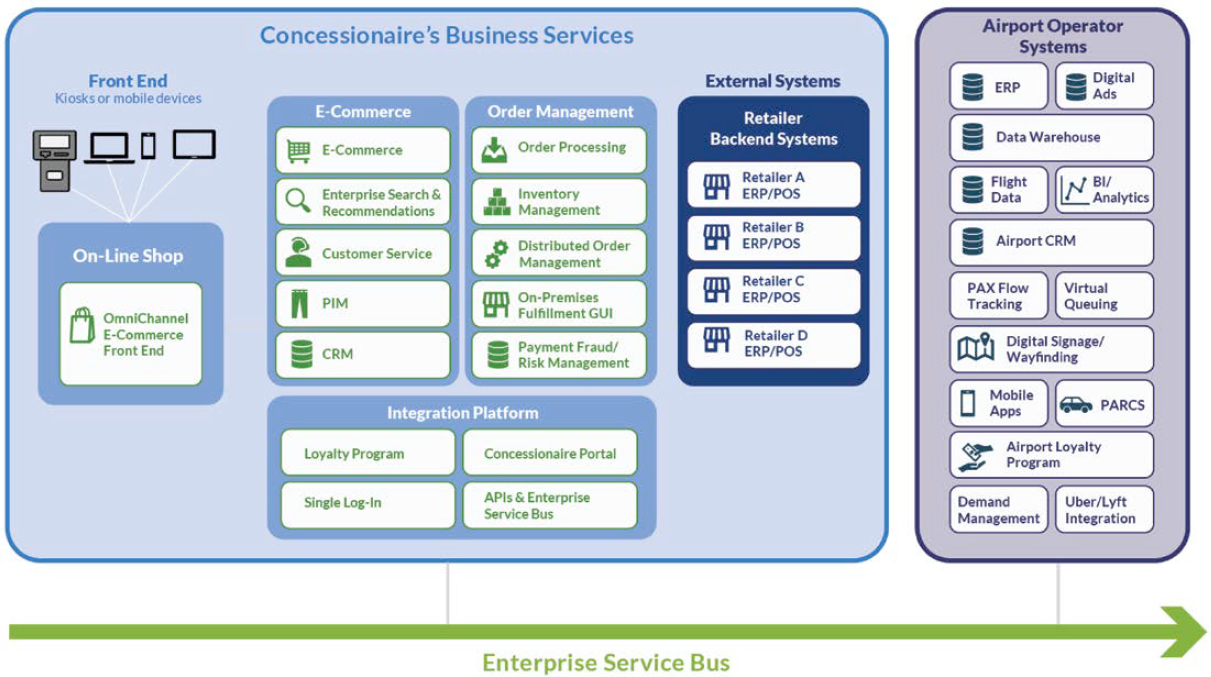

Following are system architecture considerations specifically for supporting an airport concessions technology program. Figure 12 illustrates the system architecture of a generic concessions program.

-

Integration:

- – Internal systems. Seamless integration with the airport’s core systems, such as passenger processing, flight information, parking, and loyalty programs, is crucial for a unified experience.

- – Concessionaire systems. The system should integrate with point-of-sale systems, inventory management software, and the loyalty programs used by concessionaires.

- – External systems. Integration with external systems such as airlines, ride-hailing services, and ground transportation providers can enhance passenger convenience (e.g., real-time updates, end-to-end ticketing).

-

Scalability and flexibility:

- – The architecture should be adaptable, scalable, and modular to accommodate future growth, new technologies, and evolving passenger needs.

- – It should handle fluctuations in passenger traffic and concessionaire operations.

-

Security:

- – Robust data security measures are essential to safeguard sensitive passenger data, financial transactions, and critical airport operations.

- – Compliance with data privacy regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), is crucial.

Note: PIM = product information management, GUI = graphic user interface, ERP = enterprise resource planning, POS = point-of-sale, BI = business intelligence, PAX = passenger, PARCS = parking access and revenue control system, API = application programming interface.

-

Real-time data management:

- – The system architecture should facilitate real-time data collection and analysis on passenger behavior, concessionaire performance, and inventory levels. The system architecture should handle the influx of real-time data generated from various sources—sensors, passenger devices, and operational systems.

- – This enables data-driven decision-making for optimizing operations and passenger experience.

- – Data analytics tools can be integrated to glean valuable insights for optimizing operations, resource allocation, and passenger experience.

-

Redundancy and reliability:

- – Downtime can significantly disrupt airport operations. The architecture should be designed with redundancy and failover mechanisms to ensure continuous operation.

- – System downtime can significantly disrupt airport operations. The architecture should be designed with redundancy, failover mechanisms, and disaster recovery plans to ensure continuous operation.

- – Continuously monitoring system health is essential for proactive maintenance and preventing outages.

-

Open standards:

- – Utilizing open standards and application programming interfaces (APIs) promotes easier integration with existing and future systems from a variety of vendors, thus fostering innovation and flexibility.

-

Cloud-based solutions:

- – Cloud-based systems offer scalability, flexibility, and easier maintenance as compared with on-premises solutions.

-

User interface and user experience:

- – The system architecture should support user-friendly interfaces that are seamless and intuitive for both passengers (e.g., mobile ordering, web apps, self-service kiosks) and concessionaires (e.g., inventory management).

4.5.2 E-Commerce Platform Considerations

The system architecture aims to ensure scalability and flexibility to enable seamless integration of future technology applications beyond current capabilities. An e-commerce platform manages all aspects of a concessionaire’s business, whether online or on premises (e.g., in store, at the bar). This platform unifies these channels for cohesive management, extending beyond simple sales tracking across the airport. As customers move between channels, payment details, inventory data, loyalty rewards, and other types of information are synchronized. By aligning every aspect of the concessionaire’s operations, e-commerce platforms provide consistency for all stakeholders, including consumers. These platforms cover all business offerings, such as concessionaire services, consumer services, financial services, supplier services, and data services.

The research team found that several airports are adapting to an omnichannel e-commerce platform, which supports the integration of various system components, in their digital marketplace program. While an airport may not integrate all of the functional components initially, it should consider, from the perspective of system architecture, their eventual inclusion. The following system components are being considered by airports in developing a digital marketplace program.

-

Omnichannel e-commerce platform:

- – Software solutions that enable businesses to provide a seamless and consistent customer experience across different channels and touchpoints.

- – Platforms integrate various communications and sales channels, such as websites, mobile apps, email, social media, and physical stores, thereby allowing businesses to interact with customers in a unified manner.

-

- – The omnichannel platform should seamlessly integrate all digital platforms (websites, mobile apps, kiosks) and physical touchpoints (concessions outlets, airline check-in stations, information desks) to allow passengers to transition smoothly between channels (Allan 2025).

-

Content management system (CMS):

- – Specialized digital platform designed to manage and distribute content across various digital displays, devices, and channels within an airport.

- – Allows concessionaires to manage their product listings, descriptions, prices, and promotional offers on the marketplace.

- – Ensures accurate and up-to-date information for passengers.

-

Order management system:

- – Integrates with the e-commerce platform to handle order processing, fulfillment (pick-up, delivery, or pre-order options), and inventory management.

- – Real-time communication with concessionaire systems ensures order accuracy and avoids stock-outs.

-

Customer relations management system:

- – Uses specialized software solutions designed to help airports manage and enhance their interactions with passengers and other stakeholders.

- – Leverages passenger data (e.g., loyalty programs, flight information) to personalize product recommendations and offers on the marketplace.

- – Improves passenger engagement and potentially increases sales.

-

Integration layer:

- – This critical component connects the e-commerce platform with various airport touchpoints:

- Airport website,

- Mobile app,

- Self-service kiosks, and

- Digital signage.

- – Ensures seamless product browsing and ordering across all channels.

- – This critical component connects the e-commerce platform with various airport touchpoints:

-

Payment gateway:

- – Securely processes online payment transactions within the marketplace.

- – Should be compliant with relevant payment security standards.

-

Inventory management system:

- – Connects with concessionaire systems to provide real-time inventory visibility across all locations.

- – Improves data accuracy and avoids overselling of out-of-stock items.

-

Analytics platform:

- – Tracks user behavior and purchase data on the marketplace.

- – Provides valuable insights for optimizing the platform, product offerings, and marketing strategies (Allan 2025).

-

External systems:

- – Integration with airline loyalty programs allows passengers to redeem miles for marketplace purchases.

- – Connecting with ride-hailing services or ground transportation providers can offer bundled travel and shopping packages.

By integrating these key system components via a well-defined system architecture, airports can create a robust and user-friendly omnichannel digital marketplace that enhances the passenger experience, generates additional revenue streams for concessionaires, and fosters a more connected airport ecosystem.

4.6 Infrastructure Considerations

From the perspective of IT, it is not only important to have a well-designed system architecture but also a strong infrastructure, which becomes the basis for the system architecture. The IT infrastructure enables the system architecture to function. Without physical resources, architectural design cannot be implemented. Thus, the system architecture guides the development and configuration of the IT infrastructure. It specifies what type of equipment and resources are needed to support the desired functionality.

For a concessions program, the airport should consider providing its tenants access to a private network that is separate from the public Wi-Fi network. This network would allow the airport and tenants to operate e-commerce platforms; point-of-sale systems; loyalty programs; and, potentially, self-service kiosks on a secure and reliable network rather than incur the costs and burdens associated with installing and supporting their own individual networks. The IT infrastructure would then provide the wired or wireless network, or both; servers; power; and security measures needed to make this communication occur smoothly. Additionally, the IT infrastructure would be focused on providing the essential services needed to run IT systems and applications, such as reliable Internet connectivity, data storage, and processing power, whether they are on the premises or in the cloud. The IT system architecture would define how the e-commerce platform; point-of-sale systems; loyalty programs; and, potentially, self-service kiosks all interact and share data.

Following are some key considerations for airport IT infrastructure when a concessions technology program is being developed (see also Figure 13):

-

Connectivity and power:

- – Reliable high-speed Wi-Fi. This is crucial for all technology-based concessions. Passengers will need seamless connectivity to power apps and for online ordering and digital signage.

-

- – Power availability and redundancy. Concessions will require sufficient power for equipment, point-of-sale systems, and, potentially, charging stations for passengers. Consider backup power solutions to avoid disruptions.

- – Data cabling and infrastructure. Facilitating easy installation and access to data lines for concessions is advised. Doing so allows for smooth integration with the airport’s network and concessionaire systems.

-

Physical space and design:

- – Flexibility and adaptability. Technology concessions may evolve quickly. Design spaces that can be easily modified to accommodate new equipment or layouts. Consider modular furniture and prewired outlets.

- – Security and access control. Some concessions may handle sensitive data. Ensure that there are secure areas for equipment and implement access control measures.

- – Signage and wayfinding. Clearly integrate concessions technology into the overall signage and wayfinding system. Passengers should be able to easily find and understand how to use these options.

-

Security and compliance:

- – Data security standards. Establish clear data security protocols for concessions. This protects passenger information and ensures compliance with relevant regulations. More details are provided in Section 4.7.

- – Cybersecurity measures. Implement robust cybersecurity measures to safeguard the airport’s network and concessionaire systems from cyberattacks.

- – Compliance with regulations. Ensure that all concessions technology complies with relevant regulations related to data privacy, accessibility, and fire safety.

-

Additional considerations:

- – Integration with airport systems. Explore how concessions technology can integrate with existing airport systems (e.g., flight information displays, loyalty programs) for a more cohesive passenger experience.

- – Power management strategies. Develop energy-efficient solutions to balance the increased power demands of technology with sustainability goals.

In summary, a well-developed IT infrastructure serves as the backbone for a successful enterprise-wide concessions program. It enables efficient management, data-driven decision-making, secure transactions, and a positive passenger experience.

4.7 Data Governance Considerations

4.7.1 Overall Strategy and Framework

As more data are being constantly utilized at airports for decision-making, data governance has become a major concern for airports. Data governance is essentially a set of rules and practices that dictate how an airport manages its data. Data governance encompasses everything from how data are collected and stored to who can access the data and how they are used. The goal of data governance is to ensure that data are

- Secure—protected from unauthorized access, use, or disclosure;

- Accurate—reliable and free from errors;

- Available—easily accessible to those who need the data; and

- Usable—in a format that can be readily understood and analyzed.

Airport IT groups are now focused on establishing data governance programs. Thus, airport concessions programs likewise require data governance to support their use of technology. Close coordination with the IT department can ensure streamlined adaptation.

Data governance becomes important to airport concessions technology programs for several reasons:

- Security. Airports collect a large amount of sensitive data, such as passenger information and financial data. Data governance helps to ensure that these data are protected from unauthorized access, use, or disclosure.

- Privacy. Data governance helps to ensure that passengers’ privacy rights are protected. This includes complying with data privacy regulations, such as the GDPR and the CCPA.

- Efficiency. Data governance can help to improve the efficiency of the airport’s concessions operations. By ensuring that data are accurate, complete, and up-to-date, airports can make better decisions about how to allocate resources and improve customer service.

- Compliance. Airports are subject to a variety of regulations, including those related to security, safety, and finance. Data governance can help airports comply with these regulations by ensuring that data are collected, stored, and used in a way that meets regulatory requirements.

Here are some steps that airports can take to apply data governance to technology in airport concessions programs (Nandan Prasad 2024) (see also Figure 14):

-

Establish a data governance framework:

- – Define roles and responsibilities. Clearly outline who owns the data, who is responsible for data security and privacy, and how concessions will interact with airport data.

- – Develop data governance policies. Create policies that address data classification, access controls, data retention, and breach notification procedures.

- – Standardize data collection and management. Ensure consistent data formats and collection methods across all concessions programs.

-

Implement data security measures:

- – Conduct risk assessments. Identify vulnerabilities in data collection, storage, and access within concessions programs.

- – Implement access controls. Use strong authentication protocols (e.g., strong password policies and multifactor authentication) and grant access to concessionaires on the basis of the principle of least privilege.

- – Vendor management. Clearly define expectations and responsibilities regarding data security and privacy in contracts with technology vendors.

- – Encrypt sensitive data. Protect passenger information, financial data, and other sensitive details with encryption at rest and in transit in case of a breach.

-

- – Data backup and recovery. Establish a comprehensive data backup and recovery plan to ensure that data can be restored quickly in case of a system failure or cyberattack.

- – Incident response. Develop a detailed incident response plan outlining steps to take in case of a data security incident. This should include data breach notification for passengers, containment, and remediation procedures.

-

Prioritize data privacy:

- – Develop data privacy policies. Ensure that data privacy practices comply with relevant data protection regulations such as the GDPR and the CCPA.

- – Implement data subject access request (DSAR) processes. Establish procedures to handle requests from individuals who want to know what personal data an organization holds about them, including customer requests to access, rectify, or erase their data.

- – Minimize data. Limit data collection to what is strictly necessary for the operation of the concessions program. Avoid collecting irrelevant or excessive passenger information.

-

Ensure data quality:

- – Data quality monitoring. Regularly assess data accuracy, completeness, and consistency across concessions programs.

- – Data lineage tracking. Track the flow of data from collection to use to enable easier troubleshooting and auditing.

-

Continuously improve the program:

- – Regular reviews and updates. Periodically review data governance policies and procedures to reflect evolving regulations and technological advancements.

- – Employee training. Train airport staff and concessions personnel on data governance policies and best practices to ensure the proper handling of airport data.

By implementing a data governance program, airports can help to ensure that their concessions program technology is secure, efficient, and compliant.

4.7.2 Data Governance Elements

Data stewardship, transparency, and accountability are fundamental principles that work together to support a data governance framework to ensure the successful and ethical implementation of airport concessions technology programs.

Data Stewardship: The Foundation

Data stewardship is the hands-on execution of the data governance framework (Figure 15). Data stewards are assigned specific data assets or areas (such as an airport department or specific type of data) and are responsible for ensuring that those assets comply with the data governance policies. Data stewards are typically subject matter experts from within the business units who understand the specific data and their usage. Data stewards implement practices to accomplish the goals shown in Figure 15.

Transparency: Building Trust

Transparency involves openly communicating how data are collected, used, and protected within the concessions technology program. Transparency builds trust with stakeholders, including the following:

- Passengers. Inform passengers about data collection practices, the purposes of data use, and their rights under relevant regulations, such as the GDPR and the CCPA. Utilize clear signage at concessions areas to explain data collection practices and obtain explicit consent before collecting any personal information.

- Concessionaires. Develop clear reporting structures for concessionaires to share relevant data with the airport. Ensure that they understand how data are used to evaluate their performance to create a fair and competitive environment.

Accountability: Ensuring Responsibility

Accountability ties everything together by outlining who is responsible for ensuring that the program adheres to data governance policies and ethical practices:

- Data stewards. They are held accountable for the quality, security, and accessibility of the data assigned to them.

- Airport management. The airport has the ultimate accountability for the program’s overall governance and for ensuring that the program complies with regulations and ethical standards.

- Technology vendors. The vendors who develop and implement the concessions technology should be accountable for the system’s security and data privacy measures.

Together, data stewardship, transparency, and accountability create a robust framework to support data governance in airport concessions technology programs. This fosters trust with stakeholders, protects passenger privacy, and ensures data-driven decision-making that benefits the airport, concessionaires, and, ultimately, the passengers.

4.8 Budget and Financial Analysis

An airport considering adapting technology to its concessions program will do well to consider the investment requirements during the planning stage. The investment can be from the concessionaire, the airport operator, the technology vendor, or a combination thereof. Regardless of how the program is funded, a robust financial analysis is required to make informed investment decisions. This will ensure the program’s financial sustainability and demonstrate its potential value to stakeholders.

Best practices for financial analysis include consideration of capital expenditures, operating costs, and revenue projections (Figure 16). The best practices listed here can be utilized as a guideline when an airport concessions technology program is being developed.

4.8.1 Capital Expenditures

- Detailed cost breakdown. Develop a detailed breakdown of all capital expenditures associated with the technology program. This should include acquisition costs (i.e., purchasing or leasing new hardware and software licenses), installation and configuration costs, the cost to integrate the new technology with existing systems and infrastructure, training expenses, and potential infrastructure upgrades.

- Life-cycle costing. Consider the entire life cycle of the technology when evaluating costs. Include not just the initial purchase price but also ongoing maintenance, support, and potential upgrades over the expected lifespan of the technology.

- Include contingencies. Add a buffer for unforeseen expenses, typically 10% to 20% of the total project cost.

- Funding sources. Explore various funding options, such as internal budgets, partnership agreements with concessionaires, or potential grants that are available for airport technology implementation.

- Sensitivity analysis. Conduct a sensitivity analysis to understand how changes in key assumptions, such as passenger traffic or technology lifespan, could affect capital expenditure requirements.

4.8.2 Operating Costs

-

Ongoing cost components. Identify all potential operating costs associated with the technology program:

- – Maintenance and support. Budget for ongoing maintenance of hardware and software, including technical support subscriptions and licenses and potential upgrades.

- – Training costs. Factor in the cost of training concessions staff and airport personnel on how to use the new technology effectively.

- – Data storage and security. Consider cloud storage fees or the on-premises infrastructure upgrades needed to manage data generated by the new technology.

- Cost allocation. Develop a clear method for allocating operating costs among concessionaires participating in the technology program, as applicable. Consider factors such as passenger volume, transaction fees, or a combination of both.

- Cost savings potential. Evaluate the potential cost savings that the technology program may bring. This could include reductions in labor costs, paper usage, or energy consumption. Potential cost savings may also include “soft” costs, such as favorable impacts on users (e.g., reduced wait times).

- Break-even analysis. Perform a break-even analysis to determine the volume of passenger traffic or transactions needed for the program to become financially viable.

4.8.3 Revenue Projections

- Revenue streams. Identify all potential revenue streams associated with the technology program. This could include increased concessions sales due to improved passenger experience, transaction fees charged for using the technology, or potential advertising revenue generated through the platform. Evaluate the possibility of dynamic pricing strategies to maximize revenue based on passenger flow and peak times.

- Market research. Conduct thorough market research to understand passenger behavior and willingness to pay for the benefits offered by the technology program. This will help with creating realistic revenue projections.

- Benchmarking. Benchmark your revenue projections against similar technology implementations in other airports.

- Scenario planning. Develop different revenue projection scenarios (best and worst cases) to account for potential variations in passenger traffic, technology adoption rates, and economic conditions.

4.8.4 Additional Considerations

- Concessions agreements. Review concessions agreements to determine cost-sharing models for technology implementation and ongoing expenses.

- Discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis. When evaluating the financial viability of the program, consider using a DCF analysis to account for the time value of money.

- Involvement of stakeholders. Involve key stakeholders from concessions, IT, and finance departments throughout the financial analysis process to ensure a comprehensive and accurate assessment.

- Regular review and updates. Regularly review and update your financial projections as the technology program progresses and new information becomes available.

By carefully conducting these financial analyses, airports can make informed decisions when adapting new technology for their concessions programs. The goal is to strike a balance between up-front costs, ongoing expenses, and the potential for long-term cost savings, revenue generation, and improved passenger experience.

4.9 Business Value Proposition/Return on Investment

A key factor in getting an airport concessions technology program approved and budgeted is demonstrating to airport senior management that the business value obtained far outweighs the airport’s investment in the program (Figure 17). This value should be defined and quantified on an ROI basis.

Airport senior management teams are keen on ROI for several reasons, such as limited investment options and competing programs. ROI is considered an objective measure to enable management to move beyond anecdotal evidence or the hype surrounding new technology and focus on measurable results.

Thus, presenting a business value proposition for the airport concessions technology program is important. The following best practices for defining and quantifying value can be used to determine the business value proposition or ROI for an airport concessions technology program:

-

Define value:

- – Start with goals. Align the program with airport goals such as increased passenger spending, improved operational efficiency, or enhanced customer satisfaction (see Section 4.1).

- – Identify benefits. Map the program’s features to specific benefits, such as reduced wait times, personalized offers, or data-driven decision-making for concessionaires.

-

Quantify value (ROI):

- – Identify measurable metrics (See Section 4.10 for the full list of recommended metrics):

- Revenue metrics—increased concessions sales, higher average transaction value, and new revenue streams (e.g., pre-ordering).

- Cost metrics—reduced labor costs, improved inventory management, and lower infrastructure maintenance.

- Passenger experience metrics—shorter queues, faster transactions, and improved passenger satisfaction ratings.

- – Establish baselines:

- Gather historical data on existing performance for chosen metrics (e.g., average sales per passenger, wait times).

- This sets a benchmark against which to compare improvements after implementing the technology program.

- – Identify measurable metrics (See Section 4.10 for the full list of recommended metrics):

-

Project future performance:

- – Use industry benchmarks, pilot program results (if available), or vendor projections to estimate the impact of the program on the chosen metrics.

- Calculate the ROI:

ROI = (net benefit/program cost) × 100%

net benefit = (increase in revenue + cost savings) − program cost

A positive ROI indicates that a program generates more value than it costs.

It is possible quantifying the ROI may be difficult for some airport concessions technology programs. If this is the case, there are other factors that can assist in determining a positive value for the airport, such as the following:

- Tangible benefits. Quantify qualitative benefits (e.g., passenger satisfaction) with surveys or customer feedback metrics, including the relationship between customer satisfaction and concessions spending.

- Long-term impact. Consider potential future benefits, such as increased passenger loyalty or attracting new concessionaires.

- Use cases from other airports. Some airports may have already deployed similar technology and may share their positive business value outcome and ROI.

By following these steps and considering both quantitative and qualitative factors, airport operators can make informed decisions about the business value proposition and potential ROI on airport concessions technology programs. Overall, ROI is a key metric for airport senior management because it helps them make informed decisions about resource allocation, manage risks, ensure strategic alignment, and promote data-driven decision-making for the long-term success of the airport.

4.10 Performance and Success Measurements

Besides demonstrating the value of a technology program to the airport senior management team, identifying and tracking performance and success measures are instrumental for other stakeholders and the overall success of the program.

4.10.1 Reasons for Measuring Programs

-

Gauging program effectiveness:

- – Performance and success measures act as a yardstick for assessing how well a technology program is meeting its intended goals.

- – Stakeholders can identify areas where the program excels and areas that need improvement.

-

Data-driven decision-making:

- – Objective data from performance measures empower informed decision-making to ensure that resources are allocated efficiently and that the program is on track.

- – Stakeholders can use this data to identify roadblocks, tweak program parameters, or even decide to make a course correction if the program is not delivering the desired results.

-

Demonstrating value and ROI:

- – Tracking success measures helps quantify the ROI of the technology program.

- – Demonstrating value helps secure stakeholder buy-in and continued support for the program.

-

Communication and transparency:

- – Performance measures provide a clear and objective way to communicate the program’s impact on stakeholders, including airlines, nonairline tenants, airport senior management teams, employees, and even customers.

- – This transparency builds trust and fosters a culture of data-driven decision-making within the organization.

4.10.2 Identifying and Defining Measurements

Defining performance and success measures during the planning stages of a technology program is highly recommended, for the following reasons:

- Clarifying program goals. Experiencing difficulties in identifying relevant performance measures is often a symptom of ill-defined program goals. Setting these measures early can help eliminate ambiguity and confusion on overall objectives among stakeholders, which can prevent future conflicts.

- Integration into program design. Defining these measures up front allows airport operators and concessionaires to integrate them into the program design itself. This could involve incorporating data collection mechanisms or designing functionalities that inherently generate performance data.

- Establishing benchmarks. Setting baselines early enables accurate ongoing program evaluation. This is crucial for tracking improvement and identifying areas where the program deviates from expectations.

- Facilitating resource allocation. Resources can be prioritized early on toward activities that directly contribute to achieving the program’s success measures, which avoid wastage.

- Communication and stakeholder buy-in. Defining these measures early allows for clear communication with stakeholders from the outset. Starting the program with transparency significantly reduces the opportunity for doubts to creep in, which is crucial for long-term success.

While initial planning is ideal, there is flexibility:

- Refinement during development. The initial set of measures can be refined as the program takes shape. Pilot testing or early program phases can provide valuable insight that might necessitate adjustments to the performance measures.

- Adapting to changing goals. It is acceptable to adapt the performance measures if the program goals shift midcourse. However, significant changes warrant a review of the program’s overall direction and potential resource allocation adjustments.

4.10.3 Possible Areas to Measure

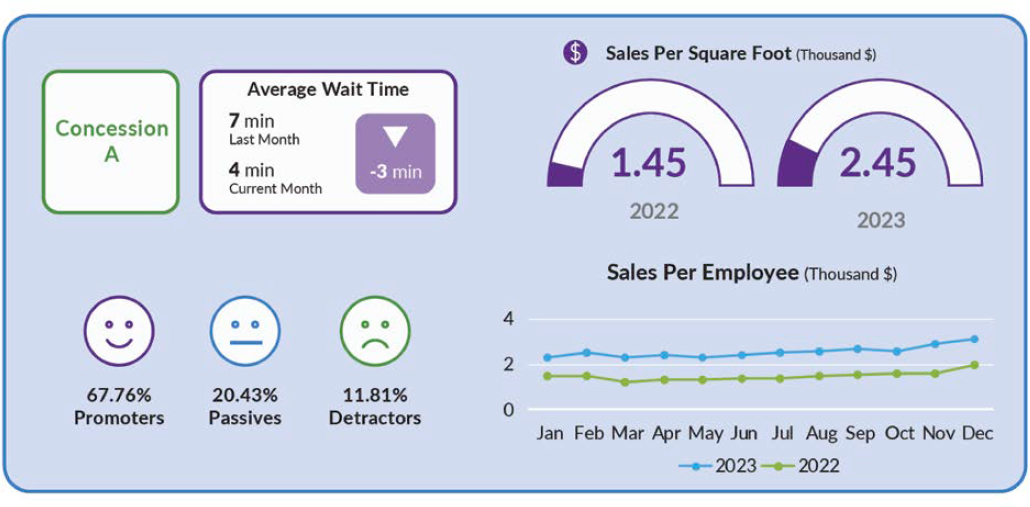

Although specific performance measures will vary depending on the goals of the airport’s concessions technology program, the following are some recommended performance measures and success measures that can be considered and categorized into different areas, as applicable (Pierangeli 2020). Figure 18 shows an example of a KPI dashboard for concessions.

-

Customer experience:

- – Reduced wait times. Track average wait times at concessions stands before and after implementing the technology.

- – Increased customer satisfaction. Conduct surveys or monitor social media sentiment to gauge customer satisfaction with the new technology.

- – Improved customer experience metrics. Monitor metrics such as the net promoter score or customer satisfaction index to measure overall customer experience.

-

Operational efficiency:

- – Increased transaction speed. Track the time it takes to complete transactions (e.g., ordering food) before and after technology implementation.

- – Reduced labor costs. Analyze whether the technology reduces the need for manual tasks, which would potentially lower labor costs.

- – Improved inventory management. Monitor whether the technology helps concessionaires manage inventory more efficiently, thereby reducing spoilage and waste.

-

Financial performance:

- – Increased concessions revenue. Track sales figures to determine whether the technology leads to higher spending by passengers.

- – Reduced operational costs. Analyze whether the technology helps concessionaires streamline operations, thereby leading to cost savings.

- – ROI. Compare the total cost of the technology program with the generated revenue or cost savings to assess its financial viability.

-

Technology adoption:

- – Concessionaire usage rate. Track how many concessionaires are actively using the new technology.

- – Customer usage rate. Monitor how many customers are utilizing the technological features offered (e.g., self-service kiosks).

- – Positive staff feedback. Gather feedback from concessions staff on their experience with the new technology to identify areas for improvement.

-

Additional considerations:

- – Data security. Track the number of security incidents or data breaches related to the concessions technology program.

- – System uptime. Monitor system uptime to ensure consistent functionality and minimal disruptions for concessionaires and passengers.

- – Increased concessionaire interest. Track the number of new concessionaires expressing interest in joining the program because of the implemented technology.

4.10.4 When to Establish Measurements

Defining performance and success measures during the planning stages of a technology program is highly recommended. This ensures alignment with goals, facilitates informed decision-making, and promotes a data-driven approach to program development and evaluation:

- Alignment with program goals. Setting performance measures early ensures that they directly align with the program’s overall goals and objectives (Project Management Institute n.d.). Clearly defined goals help determine the most relevant metrics for tracking progress and success.

- Integration into program design. Defining these measures up front allows them to be integrated into the program design itself. This could involve incorporating data collection mechanisms or designing functionalities that inherently generate performance data.

- Establishing benchmarks. Setting baselines early allows for comparison of future performance and measurement of progress over time. This is crucial for tracking improvement and identifying areas where the program deviates from expectations.

- Facilitating resource allocation. Having clear performance measures helps with resource allocation during program development and implementation. Resources can be prioritized toward activities that directly contribute to achieving the program’s success measures.

- Communication and stakeholder buy-in. Defining these measures early allows for clear communication with stakeholders from the outset. This transparency builds trust and secures stakeholder buy-in for the program because everyone understands how success will be measured.

While initial planning is ideal, there is flexibility:

- Refinement during development. The initial set of measures can be refined as the program takes shape. Pilot testing or early program phases can provide valuable insight that might necessitate adjustments to the performance measures.