Uncrewed Aircraft Systems Operational Capabilities (2025)

Chapter: Appendix B: Task 2 Survey Stakeholders Deliverables

Appendix B: Task 2 – Survey Stakeholders Deliverables

NCHRP 23-20

GUIDEBOOK FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF UAS OPERATIONAL CAPABILITIES

Survey Analysis Report

Prepared for

National Cooperative Highway Research Program

Transportation Research Board

of

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

WSP USA

1250 23rd Street NW, Suite 300

Washington, DC 20037

April 2023

List of Figures

Figure 1. Organizations Represented in Survey

Figure 2. Age of UAS Programs within Government Organizations

Figure 4. Planned Future UAS Use Cases

Figure 5. Use Cases per Organizational Role

Figure 6. Passenger Air Mobility External Relations

Figure 7. Service Provider Perspectives on Public- and Private-Sector Priorities for UAS Programs

Figure 8. OEM Perspectives on Public- and Private-Sector Priorities for UAS Programs

Figure 9. Prevalence of UAS/AAM/UTM-relevant Curricula within Academic Institutions Represented

Summary

In March 2023, a survey was developed and distributed to government agencies, industry SMEs, and academic institutions to better understand the implementation and adoption of UAS and AAM technologies.

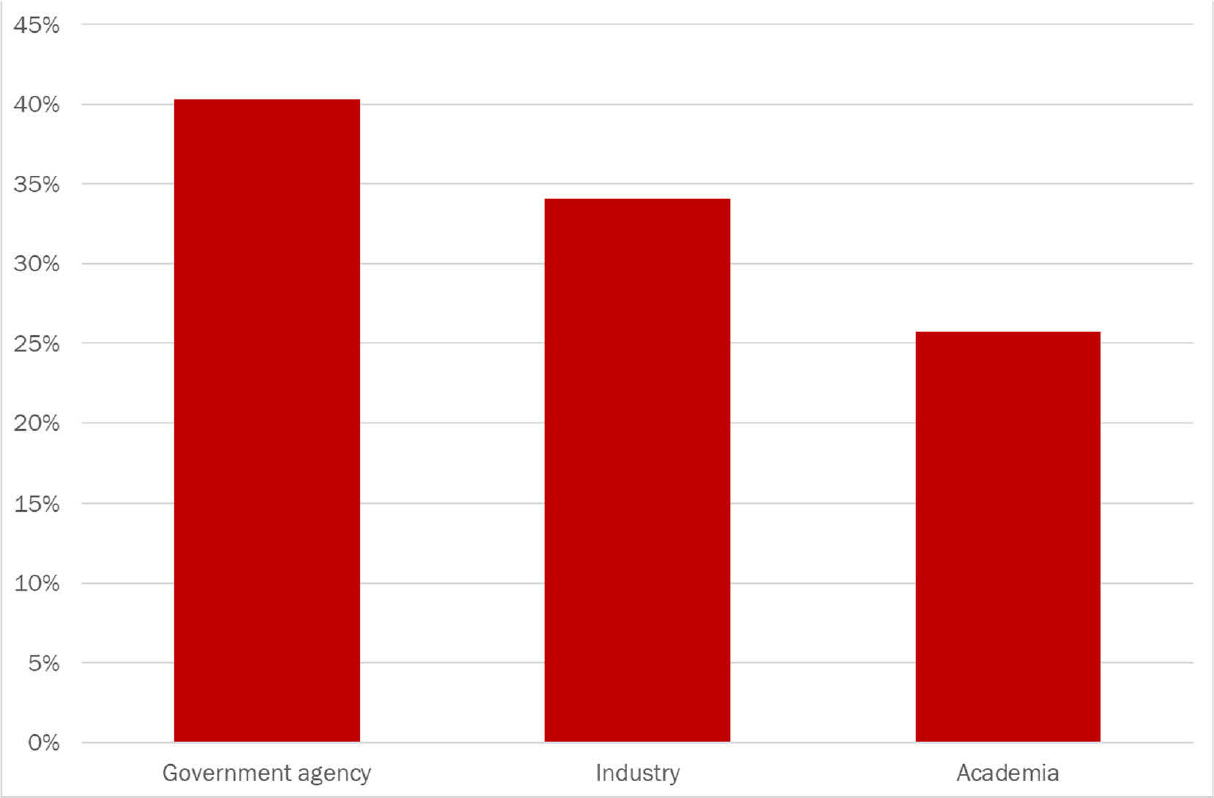

A total of 144 stakeholders responded to the survey for implementation of UAS and AAM. Of these 144 respondents, 40% represented government agencies, 34% represented industry, and 26% represented academia. Freight industry representatives did not choose to participate in the survey.

Among government respondents, a majority (72%) represented State DOTs, followed by state, regional, or local planning organizations (16%), and State Divisions or Departments of Aeronautics (10%). Finally, 2 percent of respondents represented air traffic control. Among industry groups, 47% represented service providers. Thirty-one percent represented passenger air mobility. About 22% represented UAS OEMs. The survey received 35 responses from individuals representing academia. Nearly two-thirds of respondents represented 4-year universities. Another 31% represented 2-year colleges.

Regarding government organizations in the fields of UAS and AAM, there were several key findings:

- In terms of programs and policies, most government organizations represented by the survey (79%) indicated that their organization had documented policies and procedures for UAS.

- A majority of government respondents (57%) reported their organization as having more than 10 licensed UAS remote pilots.

- Another majority (53%) reported having five or more use cases for UAS.

- About half (52%) of government organizations had a dedicated budget to support UAS programs.

Sixty percent of those government organizations surveyed reported the existence of UAS steering committees or working groups with varying levels of engagement. More than two-thirds of respondents indicated that the organization they represented did not have an AAM steering committee or working group. 37% of respondents reported collaborating with educational institutions to develop a UAS/AAM workforce pipeline.

This last finding concerning a deficit of public sector leadership in workforce development among the government organizations represented by the survey emerged as a central finding of this study. Among industry groups, the most common barrier to advancing UAS programs to maturity, mentioned by 64% of service providers and 80% of UAS OEMs, was training and workforce development. Additional findings from the survey of industry included:

- Broad support across industry for public sector leadership by State DOTs and Divisions of Aeronautics in rulemaking and regulation of AAM, general oversight, and capital infrastructure investment. Among passenger air mobility representatives, 78% believed that passenger air mobility providers should be involved in coordinating with federal, state, and local agencies in the creation of policies and regulations. Another 78% believed that these providers should assist in vertiport development. Two-thirds responded that providers have a role in maintenance, repair, and overhaul. And 44% also saw a role for themselves in assisting with UTM.

- Among service providers, 64% of these respondents indicated that service providers had a role in coordinating with federal, state, and local agencies when it comes to creating policies and regulations.

- As to perspectives on helping surface transportation agencies overcome common challenges such as understaffing, high turnover rates, securing financial backing, and adapting to rapid technological change with limited finances, OEM representatives emphasized workforce retraining programs and competitive salaries and benefits.

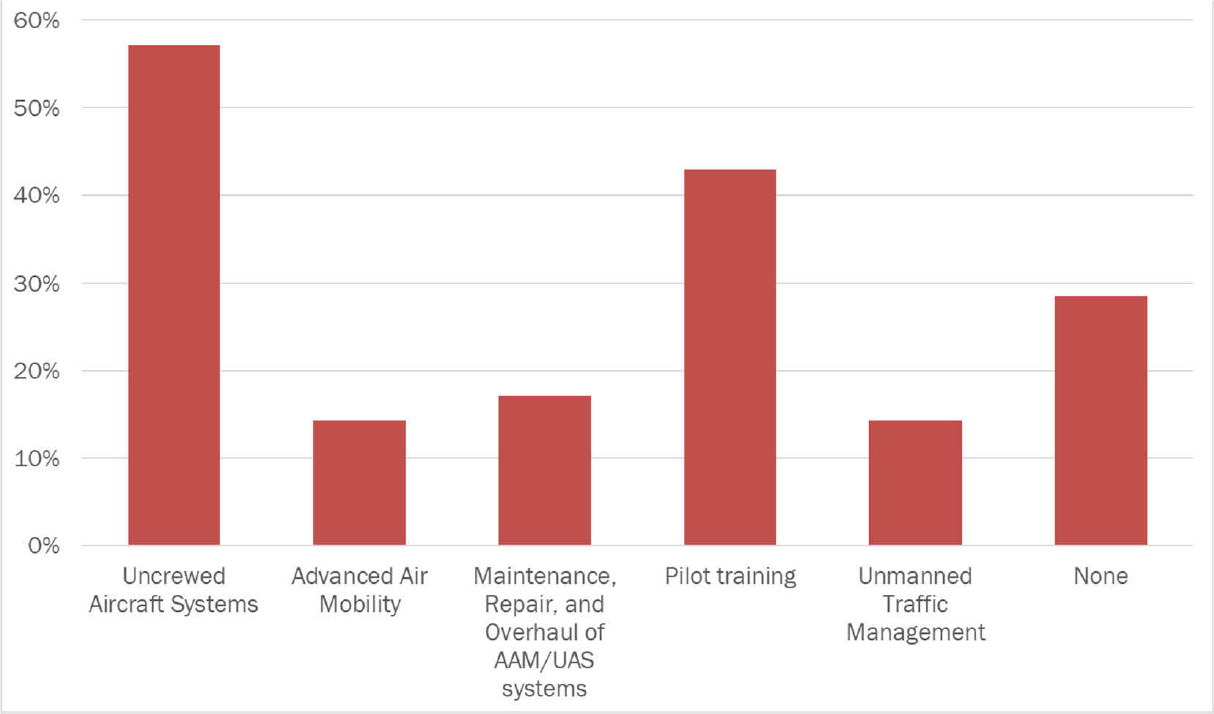

Among academic institutions, a majority (57%) indicated that UAS curricula were already being delivered. Meanwhile, smaller percentages indicated the presence of curricula related to UTM (14%), AAM (14%), and maintenance, repair, and overhaul of AAM/UAS systems (17%).

Among those surveyed, the opportunities and challenges posed by the emergence of UAS and AAM indicated strong organizational awareness, but uneven levels of engagement. Support for different forms of public sector involvement and leadership was strong across all three of the industries represented.

Among service providers and UAS OEMs, the number one priority in terms of advancing UAS programs was training and workforce development. Yet 43% of all educational institutions surveyed did not offer a curriculum to prepare students for the UAS industry, and 86% report that they lack preparatory curricula related to AAM. While several institutions indicated that they had plans to develop UAS-related curricula, most of them reported that they did not currently have a dedicated budget to either develop them or hire additional faculty to teach them.

The lack of collaboration between public sector organizations and educational institutions to develop a workforce pipeline may explain the gaps between industry demand for training and workforce development and higher education curricula. Therefore, there is an opportunity to enhancing public sector leadership in this area to bridge this divide.

Introduction

The literature review identified a variety of knowledge gaps that exist regarding the implementation and adoption of UAS and AAM technologies. As a preliminary effort to address these knowledge gaps, the research team developed a survey and identified a diverse group of stakeholders to sample.

Survey Participant Identification Strategy

The research team developed a list of potential survey participant organizations, contacts, and contact information in preparation for distributing the survey. In an effort to reach key stakeholder groups, the following organizations were asked to assist with the dissemination of the survey:

- AASHTO

- NASAO

- Association of Metropolitan Planning Organizations (AMPO)

- University Aviation Association (UAA)

- Association for Uncrewed Vehicle Systems Association (AUVSI)

- Transportation Research Board Committees

In addition to the above organizations and associations distributing the survey to their respective members, the research team also compiled a list of leading State DOTs contacts and industry representatives from industry categories such as AAM OEMs, UAS OEMs, and UAS/AAM service providers. The survey was sent directly to these compiled State DOTs and industry contacts.

The survey participant list was developed to ensure that each stakeholder group could be adequately represented. The stakeholder survey participant list was organized by category and contained the organization, point of contact name, position title, contact information, and potential level of interest (core, involved, supportive, peripheral).

Survey Development Strategy

The creation of the survey instrument for these stakeholder groups was informed by the literature review and the knowledge gaps identified therein. The survey was tailored to address specific areas of interest and gather information on the challenges and opportunities associated with UAS and AAM implementation. The survey questions aimed to address these knowledge gaps and provide a deeper understanding of the perspectives of various stakeholders.

The survey was developed to ensure the questions were focused, unbiased, and avoided survey fatigue by following best practices. For example, to achieve focus, the team determined the specific goals and objectives of the survey and then crafted questions that directly addressed project goals. To minimize bias, leading questions, double-barreled questions, and other common sources of bias were avoided. To avoid survey fatigue, the survey was kept as short as possible for each stakeholder group. Furthermore, the survey questions themselves used clear and simple language.

Most of the survey questions were multiple choice to provide quantitative data for analysis. The use of open-ended, qualitative questions was kept to a minimum, and the research team employed a strategy that also identified and mitigated bias among survey responses to these qualitative responses. Bias may be either unconscious or conscious and can significantly impact the quality and appropriateness of the subjective assessments relied upon as inputs to the survey. In general, the most effective mitigations against bias are summarized below:

- Selection of a survey facilitator who is highly experienced with eliciting consensus, making subjective assessments, and identifying and mitigating bias.

- Targeting a balanced group of experienced small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), both within and independent from the project team, who received encouragement from the survey facilitator to share their honest opinions and rationale.

Survey questions or sections were developed and customized for the following stakeholder groups:

- Government agencies, including State DOTs, divisions or departments of aeronautics, state, regional, or local planning organizations

- Industry SMEs in the sectors of passenger air mobility, freight (small and large), service provision, UAS OEMs involved in infrastructure inspections, surveying, mapping, monitoring, etc.

- Academic institutions, including 4-year and 2-year institutions as well as trade and technical schools.

Once the survey was developed, it was distributed via the online platform SurveyMonkey, and also made available via a printable PDF if requested. The survey was structured in such a way that each stakeholder group was asked to answer only relevant questions and thus took only 5-10 minutes of a participant’s time to complete.

Survey Results

A total of 144 stakeholders responded to the survey for implementation of UAS and AAM. Of these 144 respondents, 40% represented government agencies, 34% represented industry, and 26% represented academia. (Figure 1)

A. Government Agency Responses

Among government respondents, a majority (72%) represented State DOTs, followed by state, regional, or local planning organizations (16%), and State Divisions or Departments of Aeronautics (10%). Finally, 2 percent of respondents represented air traffic control.

A.1 UAS Programs and Policies

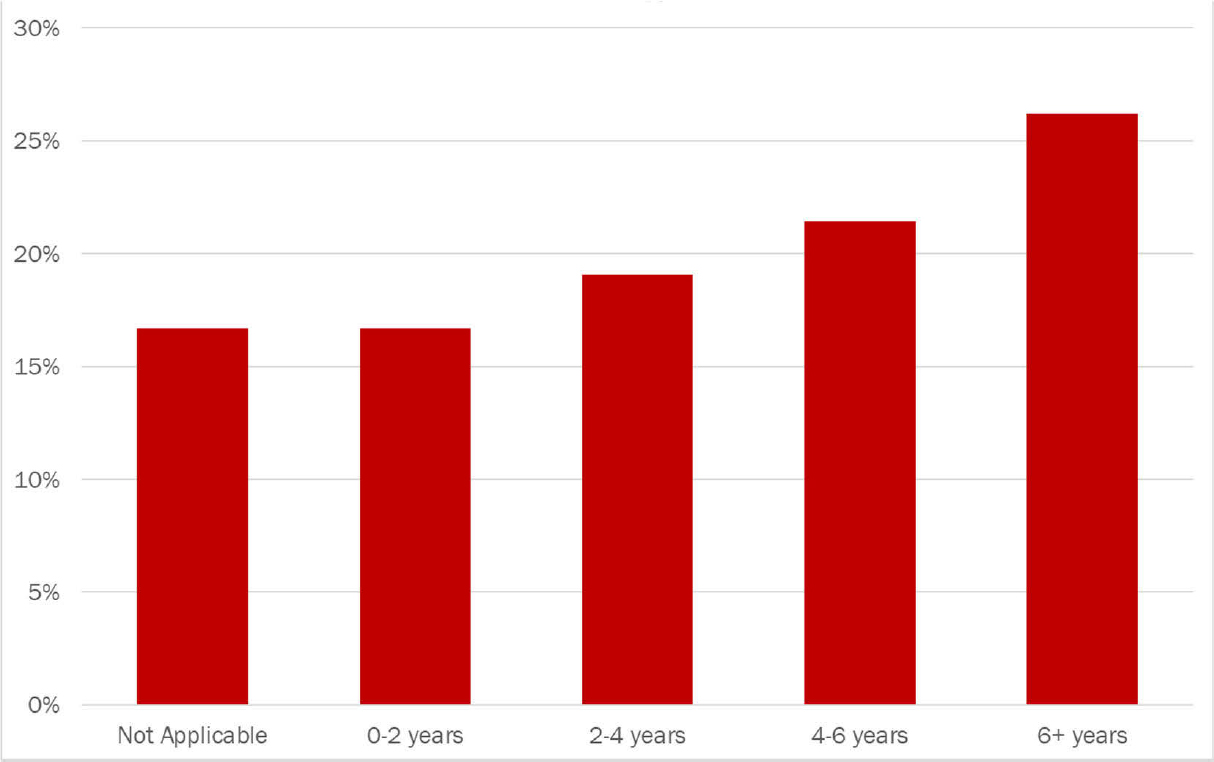

Nearly 50 percent of respondents representing government agencies reported UAS programs that were 4 or more years old. By comparison, 36 percent reported programs that were 4 years or less. There were 17 percent of the participants that reported not applicable. (Figure 2)

The vast majority of respondents (79%) indicated that their organization had documented policies and procedures for UAS. Among those representing organizations with documented policies and procedures, 56% reported that these policies and procedures were internal only, 38% indicated that they were public facing. Six percent reported not applicable.

A.2 UAS Budgets

Just over half of those reporting (52%) responded that their agency had a budget to support the UAS program. Among those representing government organizations with a UAS budget, 52% indicated that this budget was comprised of both one-time and ongoing funding. A little over one-third indicated that they relied on ongoing funding only. 4% relied solely on one-time funding.

Among those respondents whose government organizations received one-time funding, 64% reported receiving funds from FHWA grant programs. Seventy-three percent reported receiving funds from their respective state governments. 9% reported receiving one-time funds from local governments.

As for sources of ongoing funding, exactly half of government representatives indicated that their organization received ongoing funding from the federal government. There was 83% of participants that reported receiving ongoing funding from state government, while 8% received funding from local governments.

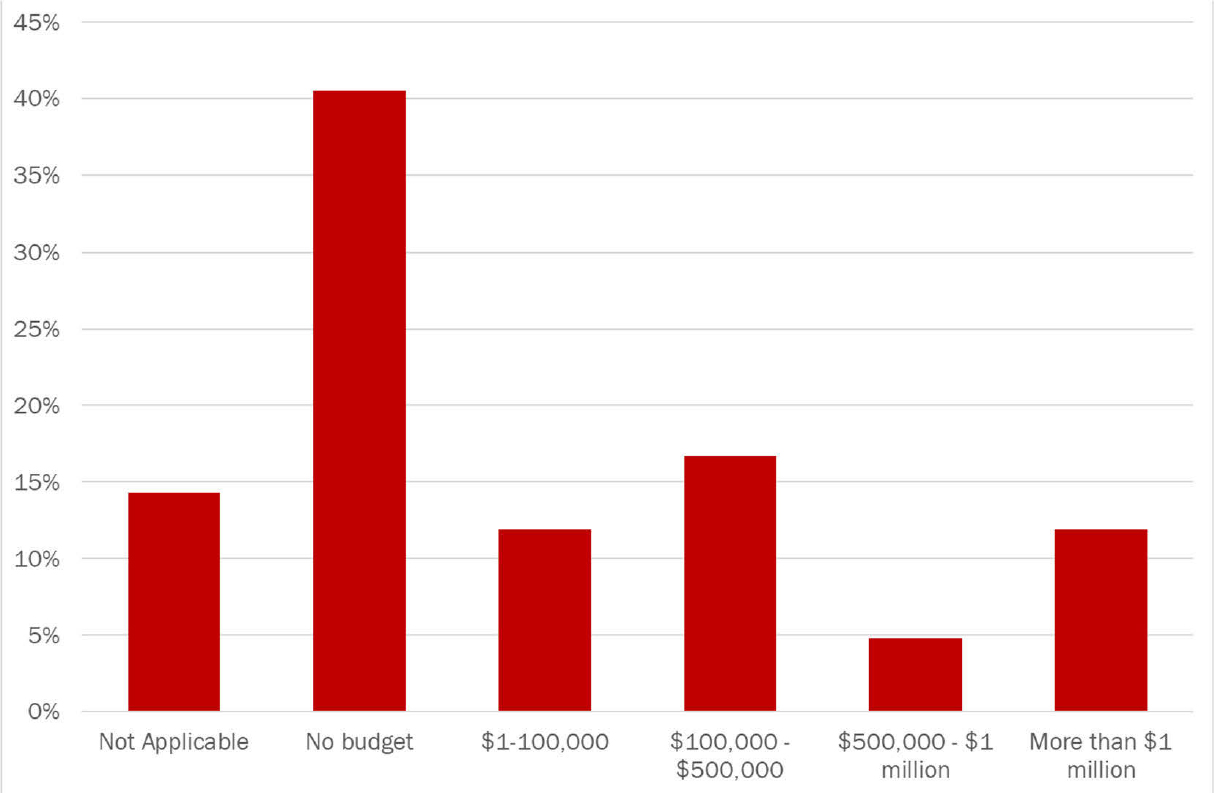

A majority (61%) indicated that these funds originated from appropriated funds, whereas 17% reported receiving both appropriated and surplus funds. Finally, among the government organization representatives, one-third reported having a current UAS budget of $100,000 or more, whereas about 12% reported budgets less than $100,000. There were 41% who reported having no UAS budget, as seen in Figure 3.

A.3 UAS Organization and Training

Sixty percent of government representatives reported that their organization had a UAS steering committee or working group. Among these, about one-third met monthly, another third met quarterly, and about 13 percent met once or twice per year. One respondent indicated that they met weekly. Two others responded meeting on an ad hoc basis.

Sixty-four percent of all government organizations represented reported having a dedicated UAS program manager. Among those that did not, 46% had plans to hire one.

A majority of organization representatives (57%) reported having more than 10 licensed UAS remote pilots. About 51% of organization representatives reported having a practical flight training component for these remote pilots. Sixty percent also reported having an internal training program.

Among those within an internal training program, two-thirds reported having a dedicated training program manager.

A.4 UAS Use Cases

More than half of all government organization representatives (53%) reported having five or more use cases for UAS. Regarding future use cases, answers varied. The word cloud in Figure 4 below provides a visual reference to the keywords that these respondents used when identifying future UAS uses, with more frequent words appearing larger.

A.5 UAS External Relations

Among respondents, strategies for communicating UAS activities to the public were broadly split among news, social media, in-person events, and the web. 3% utilized the mail. One government representative reported communicating activities during professional conferences, including the FHWA’s State Transportation Innovations Council.

Thirty-seven percent of respondents reported collaborating with educational institutions to develop a workforce pipeline.

A.6 AAM Uses and Activities

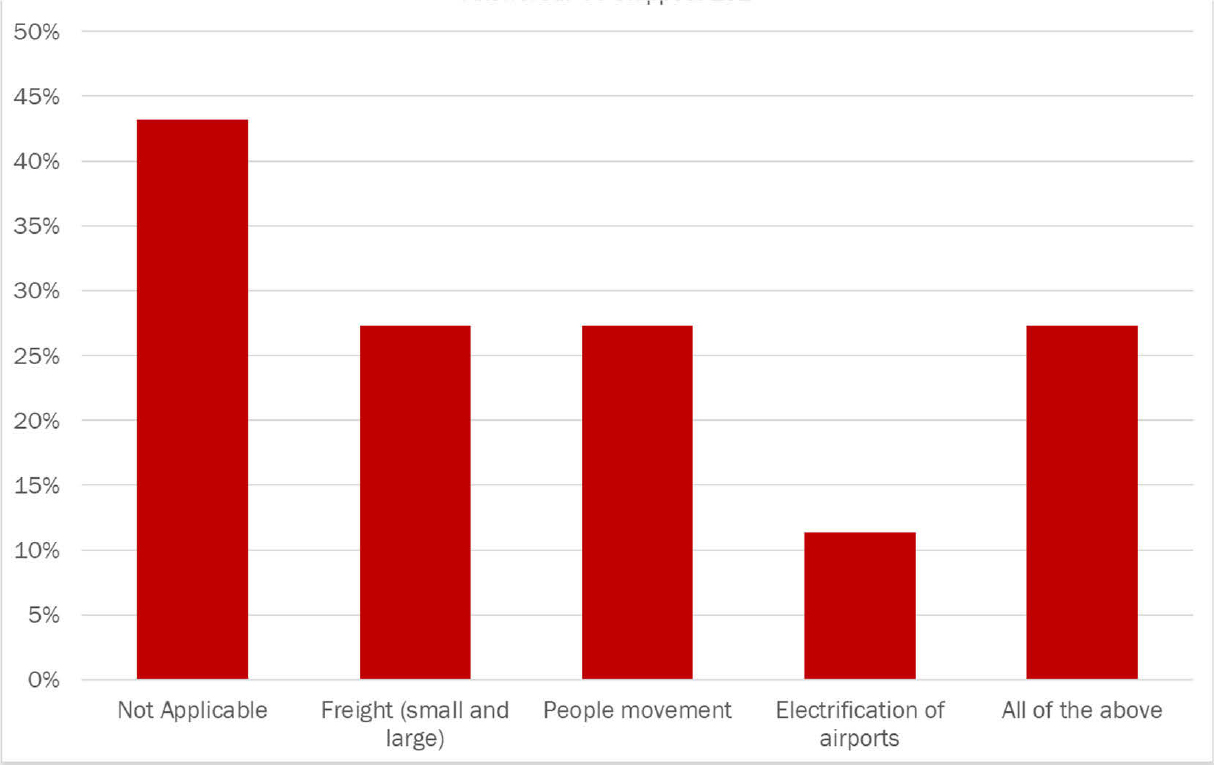

The government agencies were also asked various questions about AAM. The first question was regarding which use cases they foresee playing a role, Figure 5 depicts the results. There were 27% of government representatives who responded that their organization had a role in small and large freight. The same proportion reported that their organization had a role in people movement. About 11% of respondents indicated that their organization was involved with the electrification of airports. More than one-quarter of respondents indicated that their organization had a role in each of the aforementioned use cases, while 44% reported the question was “not applicable”.

Concerning AAM governance, nearly two-thirds of all government representatives responded that their organization should be involved in regulations and rulemaking. Just over half of respondents also said that their organization should be involved in general oversight, capital infrastructure investment, UTM and infrastructure management. 5 percent of those surveyed reported that their organization should have no role and not be involved in AAM governance.

In terms of AAM-related studies, a plurality (37%) of government representatives responded that their organization had no plans to conduct AAM-related studies. About a quarter of respondents indicated that their organizations had completed AAM-related studies or that those studies were already in-progress. Another 23% indicated that their organization planned to conduct an AAM study in the next 1-2 years.

A.7 AAM Organization

More than two-thirds of respondents indicated that the organization they represented did not have an AAM steering committee or working group. Among those nine government representatives who did report having steering committees or working groups, most reported that stakeholder participation included OEMs and/or operators, planning organizations, state and local transportation agencies, airports, academia, policymakers, and federal agencies. Four indicated that industry suppliers were also among the stakeholders included. Three reported the involvement of utility companies. Two indicated that shared- and micro-mobility transport stakeholders were also involved.

Among the nine, one reported weekly working group meetings, two reported monthly, four reported quarterly, and one reported meeting on an ad hoc basis. Another reported joining with their organization’s Aviation Advisory Committee’s ‘Aviation Technology’ subcommittee.

A.8 AAM External Relations

Most government representatives (61%) responded that communicating AAM activities to the public was not applicable to their organization. Nearly one-third of respondents indicated that their organization was collaborating with educational institutions to develop a workforce pipeline.

About one-fifth of respondents indicated that they received or planned to receive their funding for AAM activities primarily from state government. The same proportion reported receiving or planning to receive AAM funds from some combination of state government, the federal government, and private-sector partnerships.

B. Industry Responses

Among industry groups, 47% represented service providers. Thirty-one percent represented passenger air mobility. Finally, about 22% represented UAS OEMs.

B.1 Passenger Air Mobility

The survey received responses from nine passenger air mobility representatives. Among these respondents, 78% believed that passenger air mobility providers should be involved in coordinating with federal, state, and local agencies in the creation of policies and regulations. Another 78% believed that these providers should assist in vertiport development. Two-thirds responded that providers have a role in maintenance, repair, and overhaul. And 44% also saw a role for themselves in assisting with UTM. Two-thirds indicated that service provision was the only role in which passenger air mobility providers should be involved, although this may be an error with the “select all that apply” function of the question. The question may have also been unclear.

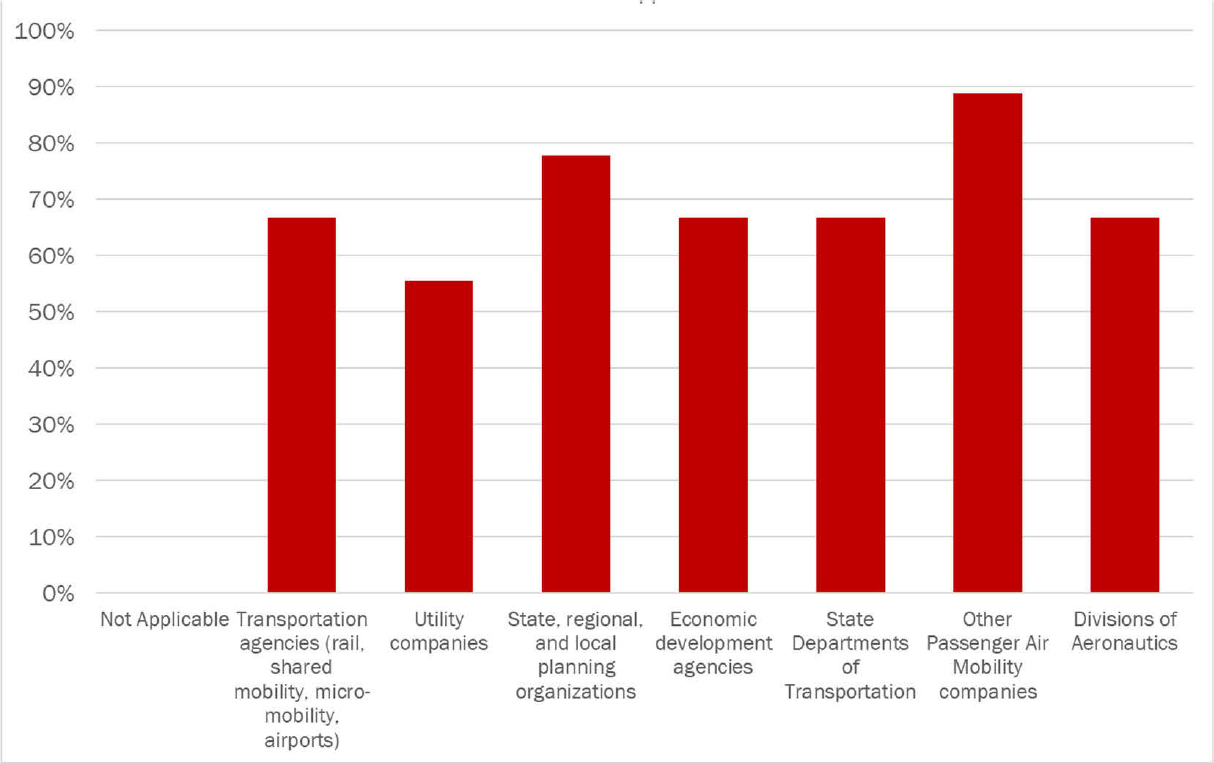

According to most passenger air mobility representatives, their organization’s interaction with the public sector was evenly distributed across transportation agencies (including rail, shared mobility, micro-mobility, and airports), state, regional, and local planning organizations, economic development agencies, State DOTs, and Aeronautics Divisions as seen in Figure 6. A majority of respondents also indicated that their organizations interact with utilities companies and other passenger air mobility companies.

Two-thirds of passenger air mobility representatives thought that State DOTs and Divisions of Aeronautics should play a role in both general oversight and in rulemaking and regulation of AAM. More than three-fourths also saw a role for these public sector organizations in capital infrastructure investment. In contrast, 11% saw a role for public transportation agencies in UTM and infrastructure management. None of the respondents indicated that these public agencies had no role in the AAM field.

22% of respondents indicated that their organization opposed an open and agnostic UTM system.

In terms of community outreach, two-thirds of respondents indicated that their organizations conducted outreach in target markets. Among them, 83% held in-person events (including community meetings), two-thirds relied upon news outlets to distribute information, half used social media platforms, and one-third used a website.

In terms of future activities in the AAM space, 78% of respondents indicated that their organizations plan to integrate with multimodal transportation nodes. All nine respondents reported an interest in pursuing public-private partnerships for infrastructure capital investment. Regarding AAM workforce recruitment, 78% of organizations were considering technical schools. Two-thirds were considering in-house workforce development or targeting universities.

B.2 Freight

The survey received no responses from small or large freight industry representatives.

B.3 Service Providers

The survey received responses from 11 service provider representatives. Sixty-four percent of these respondents indicated that service providers had a role in coordinating with federal, state, and local agencies when it comes to creating policies and regulations. Smaller numbers supported a role for

service providers in vertiport development (46%), UTM (27%), and maintenance, repair, and overall (9%). Forty-six percent responded that they should be involved in service provision only.

In terms of their view on the roles that State DOTs and Aeronautics divisions should play in AAM, including UAS and UTM, nearly three-quarters of respondents advocated for regulation and rulemaking, as well as general oversight. Slightly fewer (64%) saw a role for transportation agencies in capital infrastructure investment. Finally, a majority (55%) also advocated for UTM and infrastructure management. No service provider representatives reported that there was no role for transportation agencies in UAS/UTM integration.

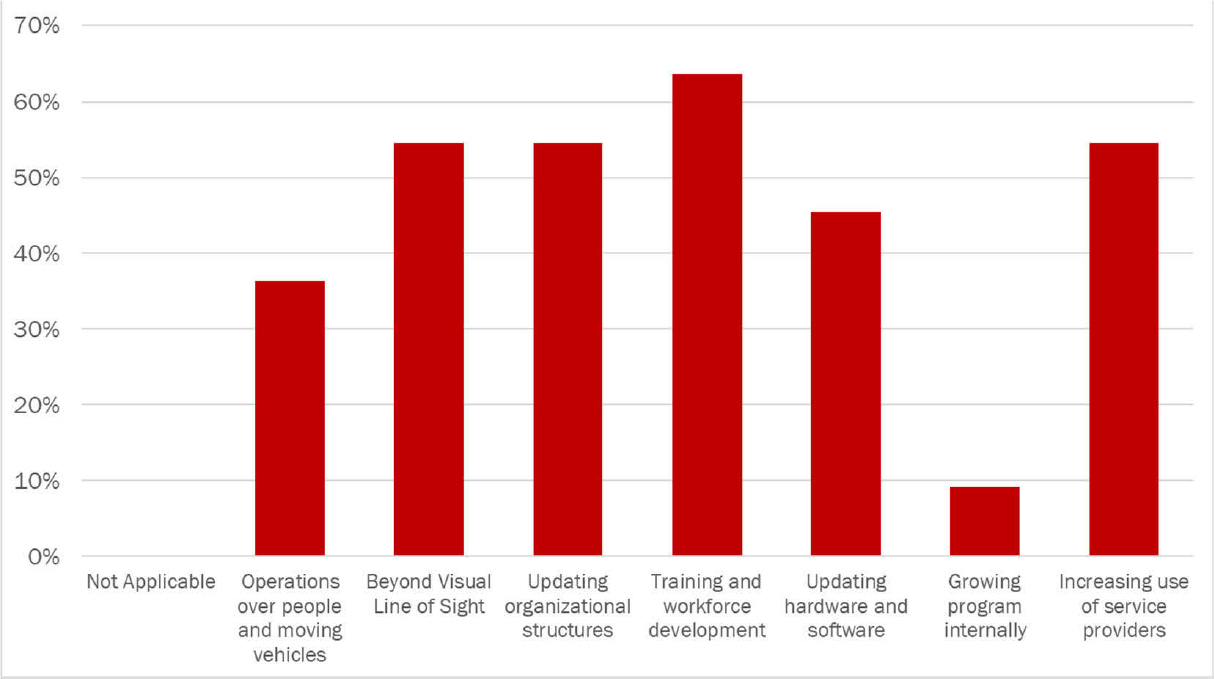

When it comes to helping advance UAS programs to maturity, service provider representatives favored a wide range of public- and private-sector priorities—including training and workforce development (64%), using BVLOS (55%), updating organizational structures (55%), increasing use of service providers (55%), updating hardware and software (46%), and performing operations over people and moving vehicles (36%). By comparison, 9% indicated that growing UAS programs internally should be a priority as seen in Figure 7.

When it comes to helping surface transportation agencies overcome common challenges such as understaffing, high turnover rates, securing financial backing, and adapting to rapid technological change with limited finances, service provider representatives articulated the following strategies:

- Forging partnerships to allow vendors to operate

- Federal funding eligibility

- Workforce development and capacity-building efforts

- Development of multi-institutional coalitions

- Partner with professional societies

- Training dedicated staff

- Public-private partnerships

- Pilot programs

B.4 UAS OEMs

Among UAS OEMs, five representatives responded to the survey. These representatives saw roles for State DOTs and Aeronautics in UAS/AAM/UTM in capital infrastructure investment (80%), general oversight (60%), regulation and rulemaking (60%), and UTM and infrastructure management (40%). None of the representatives saw no role for transportation agencies in AAM.

In terms of UAS categories, one respondent represented an OEM that intends to certify under or comply with FAA Category 2, while another represented an OEM working under Category 3. The other three respondents indicated this question did not apply to them.

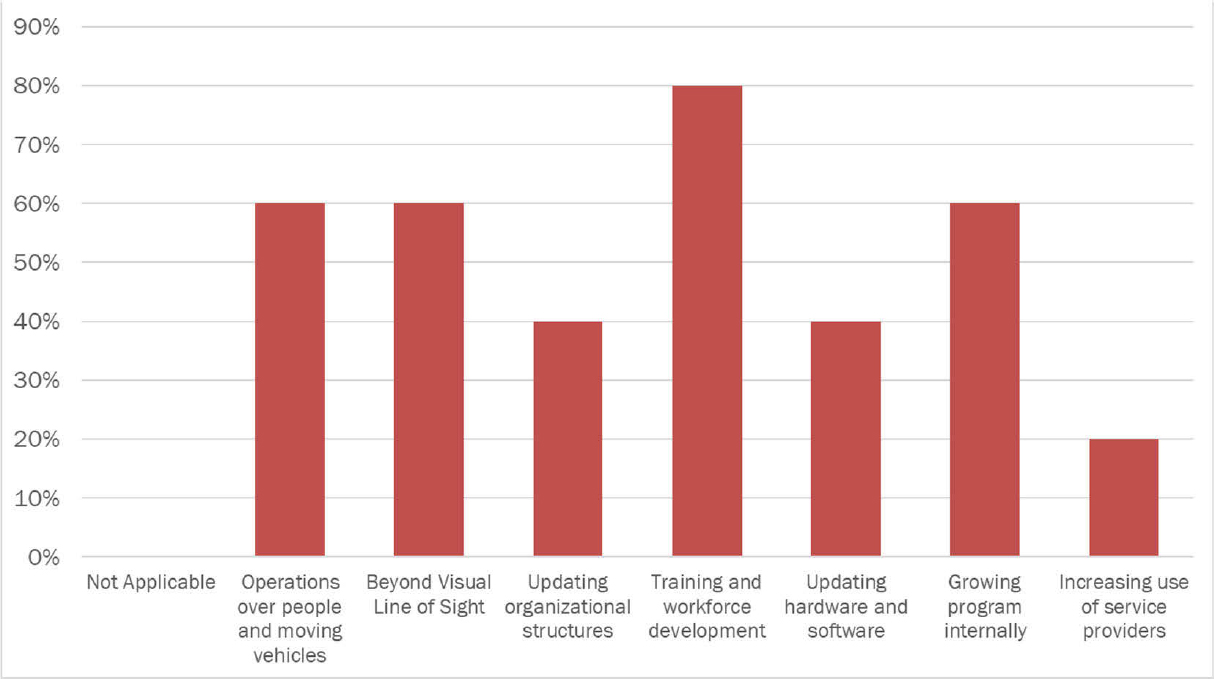

Concerning the role of public- and private-sector organizations in helping UAS programs mature, OEM representatives articulated the following priorities as depicted in Figure 8: training and workforce development (80%), operations over people and moving vehicles (60%), operating BVLOS (60%), growing UAS programs internally (60%), updating hardware and software as well as organizational structures (both 40%), and finally increasing the use of service providers (20%).

As to perspectives on helping surface transportation agencies overcome common challenges (such as understaffing, high turnover rates, securing financial backing, and adapting to rapid technological change with limited finances), OEM representatives emphasized the following strategies:

- Workforce retraining programs

- Competitive salaries and benefits

- Secured funding

- Employ consultants for the technical aspects of UAS

- Go to industry for information on changing technologies

- Consider the impacts of UAS and potential for taxes and fees to support infrastructure development and regulatory budgets.

Finally, as relates to recruitment methods for workforce development, OEM representatives favored in-house recruiting (40%) over universities (20%) or technical schools (0%).

C. Academia Responses

The survey received 35 responses from individuals representing academia. Nearly two-thirds of respondents represented 4-year universities. Another 31% represented 2-year colleges. Finally, one respondent was a postdoctoral researcher, and another two represented think tanks.

Regarding the prevalence of UAS/AAM/UTM-relevant curricula within the academic institutions represented, a majority of respondents (57%) indicated that the institution they represent currently had a curriculum to prepare students for UAS industries. A smaller number (43%) offered pilot training. Fewer programs still offered courses relevant to AAM, maintenance, repair, and overhaul of AAM/UAS systems, and UTM. Twenty-nine percent of respondents indicated that their academic institution did not offer any curricula relevant to these industries.

Among those institutions that did not currently offer UAS/AAM/UTM-relevant curricula, one-third of representatives indicated that their academic institution planned to develop both UAS and UTM coursework and 22% represented institutions with plans to develop AAM curricula only. Finally, 11 percent indicated plans to offer pilot training.

Finally, nearly two-thirds of respondents representing academic institutions indicated that they had the support of leadership to develop curriculum or grow programs to meet AAM/UAS workforce development needs. However, nearly 75% of this group responded that they did not currently have a dedicated budget to develop these programs and/or hire additional faculty to teach these courses.

Analysis

The analysis methodology involved providing a descriptive summary of the statistics captured by the survey. Due to the nature of the survey – small sample size, convenience-based sampling strategy, and combination of qualitative and quantitative responses – a statistical analysis was not conducted.

Among those surveyed, the opportunities and challenges posed by the emergence of UAS and AAM indicated strong organizational awareness, but uneven levels of engagement. Support for different forms of public sector involvement and leadership was strong across all three of the industries represented.

Among service providers and UAS OEMs, the number one priority in terms of advancing UAS programs was training and workforce development. Yet 43% of all educational institutions surveyed did not offer a curriculum to prepare students for the UAS industry, and 86% report that they lack preparatory curricula related to AAM. While several institutions indicated that they had plans to develop UAS-related curricula, most of them reported that they did not currently have a dedicated budget to either develop them or hire additional faculty to teach them.

The lack of collaboration between public sector organizations and educational institutions to develop a workforce pipeline may explain the gaps between industry demand for training and workforce development and higher education curricula. Therefore, there is an opportunity to enhancing public sector leadership in this area to bridge this divide. These gaps may be related to the fact that the majority of public sector organizations surveyed in this study are not collaborating with educational institutions to develop a workforce pipeline.

This information and data from the survey combined with the previously completed literature review will serve as the foundation for the Task 3 Gap Analysis. The research team will take a deeper dive in the data and identify existing gaps which still need to be addressed.

Survey Questions:

These are the survey questions that were developed by the research team and reviewed by the project panel, these were then built into SurveyMonkey to which was the selected platform for distribution. The survey can be taken here: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/NCHRP2320

Question 1: What organization do you represent?

- Government Agency

- Industry

- Academia

If they select government agency, then which entity best describes you:

- Department of Transportation

- Division or Department of Aeronautics

- State, regional, or local planning organization (*will be directed to take only the AAM section)

If they select Industry, then which entity best describes you:

- Passenger Air Mobility

- Freight (small and large)

- Service Providers

- UAS OEMs (infrastructure inspections, surveying, mapping, monitoring, etc.)

If they select Academia, then which entity best describes you:

- 4 Year University

- 2 Year College

- Trade School

- Technical School

- Other__________

Government Agency Questions (there will be two sections UAS and AAM) (*DOTs and Divisions of Aeronautics should be directed to take both sections, the planning organizations will only take the AAM section)

UAS Section Questions:

How long has the organization had an official UAS program?

- 0-2 years

- 2-4 years

- 4-6 years

- 6+ years

- Not applicable

Do you have documented policies and procedures for UAS?

- Yes

- If they answer yes, then ask: Are these policies and procedures public facing or internal?

- Public facing

- Internal only

- No

- Not applicable

Do you have a budget to support the UAS program?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

- If they answer yes, then ask the following question:

Was it one-time funding or ongoing funding?

- One-time funding

- Ongoing funding

- Both a and b

- Not applicable

- If the answer is one-time funding, then ask: Was it funding from: (select all that apply)

- FHWA grant program

- State

- if the answer is state then ask: Was it appropriated funds or surplus funds or a and b?

- Local

- If the answer is ongoing funding, then ask: Is the funding from (select all that apply)

- Federal

- State

- If the answer is state, then ask: Is it appropriated funds or surplus funds or a and b?

- Local

What is the current UAS budget?

- No budget

- $1-100,000

- $100,000 - $500,000

- $500,000 - $1 million

- $1million plus

- Not applicable

Does the organization have a UAS steering committee/working group?

- Yes

- If the answer is yes, then ask: How often does the steering committee/working group meet?

- Monthly

- Quarterly

- Bi-annually

- Annually

- No

- Not applicable

Does the organization have a dedicated UAS program manager?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

- If the answer is no, then ask: Do you have plans to hire a dedicated UAS program manager?

- Yes

- No

How many licensed UAS remote pilots does the organization currently have?

- None currently have their Remote Pilot Certificate (License)

- 1-4

- 5-10

- More than 10

- Not applicable

Does the organization have a training program?

- Internal

- If yes, do you have a dedicated training program manager?

- Yes

- No

- External

- None

- Not applicable

Do you have a practical flight training component for UAS remote pilots?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

How many use cases are you using UAS?

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 5+

- Not applicable

What are your planned future UAS use cases?

- Open-ended response

How do you communicate UAS activities to the public? (Select all that apply)

- News

- Social Media

- Website

- In-person events

- Other ______________________

- Not applicable

Are you collaborating with any educational institutions to develop a workforce pipeline?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

AAM Section Questions:

AAM is the use of electric or hybrid-electric aircraft to move people, freight (small and large), and the electrification of airports.

Which of these use cases does the organization you are representing have a role in?

- Freight (small and large)

- People movement

- Electrification of airports

- All of the above

- Not applicable

Which of the following areas should the organization you are representing be involved in? (Select all that apply)

- Regulator/Rule making

- General oversight

- Capital infrastructure investment

- UTM and Infrastructure management

- No role, should not be involved

- Not applicable

Does the organization you represent have an AAM steering committee/working group?

- Yes

- If yes, then ask: Which of the following stakeholders are a part of the AAM working group? (Select all that apply)

- OEMs and/or operators

- Planning organizations

- Industry suppliers

- State and local transportation agencies

- Airports

- Academia

- Shared and micro-mobility transportation organizations

- Utilities companies

- Policy makers

- Economic development organizations

- Federal agencies

- Also, if yes, then ask: How often does the AAM working group meet?

- Monthly

- Quarterly

- Bi-annually

- Annually

- No

- Not applicable

Has the organization you represent completed or plan to execute AAM-related studies?

- Completed

- In-progress

- Plan to in 1 year

- Plan to in 2 years

- No plan to do so at this time

- Not applicable

How does the organization you represent communicate AAM activities to the public? (Select all that apply)

- News

- Social Media

- Website

- In-person events

- Other ______________________

- Not applicable

What funding sources is the organization using or plans to use for AAM?

- Public-private partnerships

- Federal

- State

- Other______________________

- Not applicable

Is the organization you represent collaborating with any educational institutions to develop a workforce pipeline?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

Industry Stakeholders Questions:

If they select industry, from the first question of the survey then which entity best describes you:

- Passenger Air Mobility

- Freight (small and large)

- Service Providers

- UAS OEMs (infrastructure inspections, surveying, mapping, monitoring, etc.)

- Not applicable

Each of these industry stakeholder groups will have questions.

Passenger Air Mobility Questions:

Which of the following roles should passenger air mobility providers be involved in? (Select all that apply)

- Service provider only for passenger air mobility

- Assist in vertiport development

- Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul

- UTM

- Coordinating with federal, state, and local agencies on creating policies and regulations

- Not applicable

Which entities are the organization you represent currently working with? (Select all that apply)

- Transportation agencies (rail, shared mobility, micro-mobility, airports)

- Utility companies

- State, regional, and local planning organizations

- Economic development agencies

- State DOTs

- Other passenger air mobility companies

- Divisions of Aeronautics

- Not applicable

What role should State DOTs and Divisions of Aeronautics be playing in AAM? (Select all that apply)

- Regulator/Rule making

- General oversight

- Capital infrastructure investment

- UTM and Infrastructure management

- No role, should not be involved

- Not applicable

Does the organization you represent intend to integrate with multimodal transportation nodes?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

Is the organization you represent interested in pursuing Public-Private Partnerships for infrastructure capital investment?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

Does the organization you represent support an open and agnostic UTM system?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

What recruitment methods is the organization you represent considering for workforce development?

- Universities

- Technical Schools

- In-house

- No plan, have not thought about this yet

- Not applicable

Is the organization you represent running any community outreach in target markets?

- Yes

- If yes, which of the following methods are being used? (All that apply)

- News

- Social media

- Website

- In-person events

- Other_____________

- No

- Not applicable

Freight (Small and Large) Questions:

Which of the following roles should freight (small and large) providers be involved in? (Select all that apply)

- Service provider only for freight movement and delivery

- Assist in vertiport development

- Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul

- UTM

- Coordinating with federal, state, and local agencies on creating policies and regulations

- Not applicable

Which entities is the organization you represent currently working with? (Select all that apply)

- Transportation agencies (rail, shared mobility, micro-mobility, airports)

- Utilities companies

- State, regional, and local planning organizations

- Economic development agencies

- State DOTs

- Passenger Air Mobility companies

- Divisions of Aeronautics

- Not applicable

What role should State DOTs and Divisions of Aeronautics be playing in AAM? (Select all that apply)

- Regulator/Rule making

- General oversight

- Capital infrastructure investment

- UTM and Infrastructure management

- No role, should not be involved

- Not applicable

Does the organization you represent intend to integrate with multimodal freight hubs?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

Is the organization you represent interested in pursuing Public-Private Partnerships for infrastructure capital investment?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

Does the organization you represent support an open and agnostic UTM system?

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

What recruitment methods is the organization you represent considering for workforce development?

- Universities

- Technical Schools

- In-house

- No plan, have not thought about this yet

- Not applicable

Is the organization you represent running any community outreach in target markets?

- Yes

- If yes, which of the following methods are being used?

- News

- Social media

- Website

- In-person events

- Other_____________

- No

- Not applicable

Service Providers Questions:

Which of the following roles should service providers be involved in? (Select all that apply)

- Services only

- Assist in vertiport development

- Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul

- UTM

- Coordinating with federal, state, and local agencies on creating policies and regulations

- Not applicable

What role should State DOTs and Divisions of Aeronautics be playing in AAM, including Uncrewed Aircraft Systems integration and UTM? (Select all that apply)

- Regulator/Rule making

- General oversight

- Capital infrastructure investment

- UTM and Infrastructure management

- No role, should not be involved

- Not applicable

How can State DOTs, local agencies, public and private-sector organizations increase the maturity of UAS programs? (Select all that apply)

- Operations over people and moving vehicles

- Beyond Visual Line of Sight

- Updating organizational structures

- Training and workforce development

- Updating hardware and software

- Growing program internally

- Increasing use of service providers

- Not applicable

Surface transportation agencies experience some of the following challenges: understaffing, high turnover rates, securing dedicated UAS budget, and keeping up with rapidly changing technology with limited budgets. What are some strategies that can be used to overcome these challenges?

- Open response___________________________

Uncrewed Aircraft Systems Original Equipment Operators Questions:

What role should State DOTs and Divisions of Aeronautics be playing in AAM, including Uncrewed Aircraft Systems integration and UTM? (Select all that apply)

- Regulator/Rule making

- General oversight

- Capital infrastructure investment

- UTM and Infrastructure management

- No role, should not be involved

- Not applicable

Which FAA UAS category does the organization you are representing intend to certify under or comply with?

- Category 2

- Category 3

- Category 4

- Not applicable

How can State DOTs, local agencies, public and private-sector organizations increase the maturity of UAS programs? (Select all that apply)

- Operations over people and moving vehicles

- Beyond Visual Line of Sight

- Updating organizational structures

- Training and workforce development

- Updating hardware and software

- Growing program internally

- Increasing use of service providers

- Not applicable

Surface transportation agencies experience some of the following challenges: understaffing, high turnover rates, securing dedicated UAS budget, and keeping up with rapidly changing technology with limited budgets. What are some strategies that can be used to overcome these challenges?

- Open response___________________________

What recruitment methods is the organization you represent considering for workforce development?

- Universities

- Technical Schools

- In-house

- No plan, have not thought about this yet

- Not applicable

Academia Questions:

Does the educational institution you represent currently have a curriculum to prepare students for the following industries? (Select all that apply)

- Uncrewed Aircraft Systems

- AAM

- Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul of AAM/UAS systems

- Pilot training

- Unmanned Traffic Management

- None

- If none, then does the educational institution plan to develop curriculum to prepare students for any of the following industries? (Select all that apply)

- Uncrewed Aircraft Systems

- AAM

- Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul of AAM/UAS systems

- Pilot training

- Unmanned Traffic Management

Do you have leadership support to develop curriculum or grow programs related to AAM/UAS workforce development needs?

- Yes

- If yes, then do you have a dedicated budget to develop these programs and/or hire additional faculty to teach these courses?

- Yes

- No

- No

- Not applicable