Uncrewed Aircraft Systems Operational Capabilities (2025)

Chapter: Appendix A: Task 1 Literature Review Deliverables

Appendix A: Task 1 – Literature Review Deliverables

NCHRP 23-20 GUIDEBOOK FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF UAS OPERATIONAL CAPABILITIES

Technical Memorandum - Literature Review

Prepared for

National Cooperative Highway Research Program

Transportation Research Board

of

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

WSP USA

1250 23rd Street NW, Suite 300

Washington, DC 20037

February 2023

Table of Contents

Future UAS Use Cases and Opportunities

AAM Use Cases and Opportunities

Cross-Jurisdictional Collaboration

Table of Tables

Table 1: Examples of AAM aircraft with associated use cases and operational capabilities

Table 2: Overview of State Legislation for UAS or AAM Related Activities

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Literature review methodological approach

Figure 2: Examples of UAS for package delivery

Figure 3: NASA Depiction of AAM Ecosystem

Figure 4: NASA’s organizational framework for addressing AAM obstacles

List of Acronyms

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| AAM | Advanced Air Mobility |

| AASHTO | American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BVLOS | Beyond Visual Line of Sight |

| CFR | Code of Federal Regulations |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| FDOT | Florida Department of Transportation |

| FHWA | Federal Highway Administration |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NAS | National Airspace System |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| ODOT | Ohio Department of Transportation |

| RAM | Regional Air Mobility |

| STOL | Short Takeoff and Landing |

| UAM | Urban Air Mobility |

| UAS | Uncrewed Aircraft Systems |

| UDOT | Utah Department of Transportation |

| UTM | Unmanned Traffic Management |

| VTOL | Vertical Takeoff and Landing |

Introduction

The objective of the Task 1 Literature Review is to identify the current state of the literature and industry regarding UASs and Advanced Air Mobility (AAM). Due to the fast-evolving nature of the industry, the literature review focuses primarily on work from the last 2 years but does account for key research beyond that timeframe. The research team executed a comprehensive review of published and unpublished research and other industry activities, including, but not limited to:

- Industry whitepapers and technical blueprints

- Research institution, foundation and non-profit reports

- Airport initiatives for future mobility and sustainability

- Municipal strategic documents and outreach to industry

- Major press releases and newspaper articles

- Federal, state and local legislation regarding general aviation, AAM and UAS

- Expert interviews with industry and airport influencers

- Community Air Mobility Initiative

- NASA AAM Ecosystem Working Groups

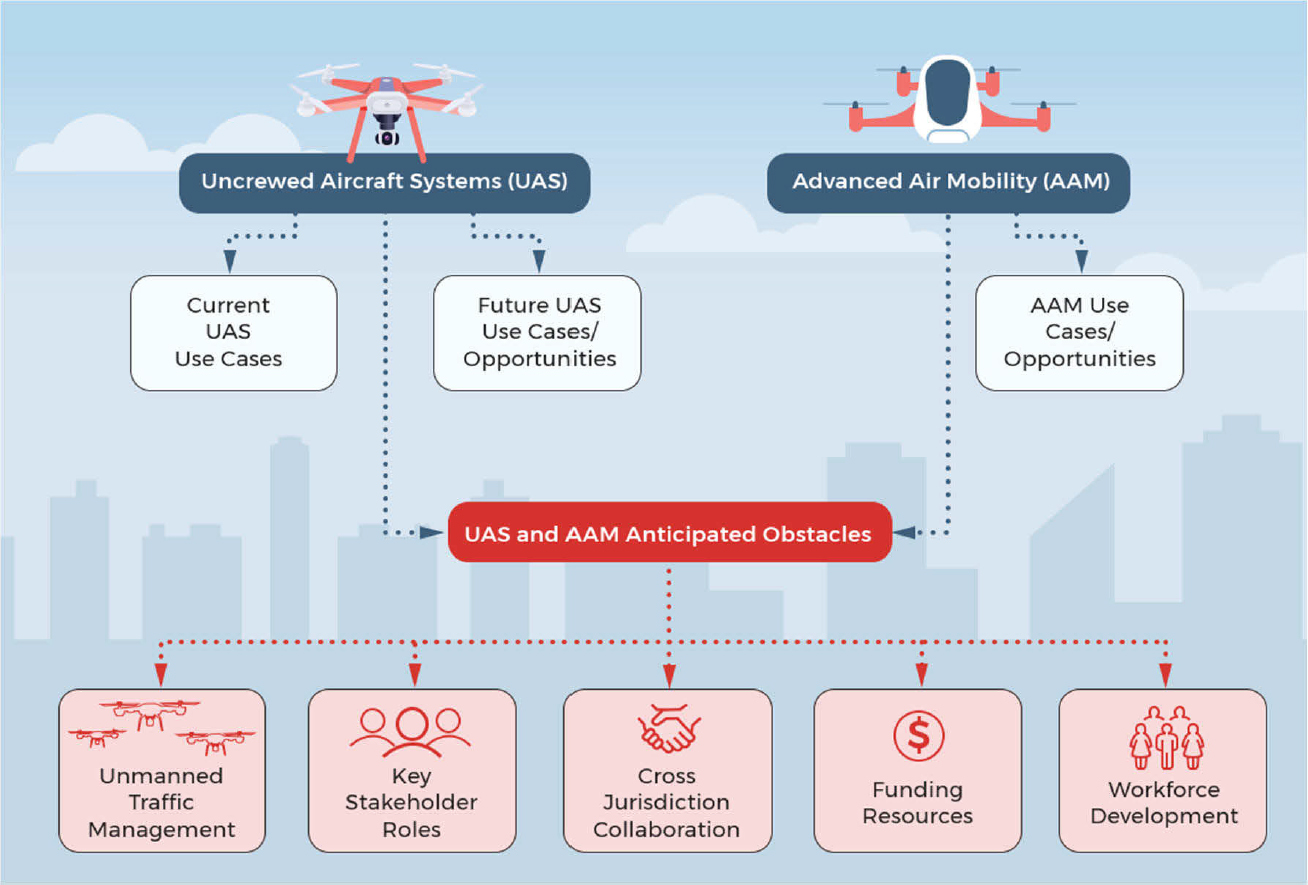

This extensive review identifies literature and industry knowledge gaps that will be further researched throughout this project. The research team developed the literary map in Figure 10 to guide the thorough literature review efforts. The methodological approach depicted was established to conduct the literature review within an organized flow and by topic.

Uncrewed Aircraft Systems

UAS is a growing industry with a plethora of commercial and hobbyist use cases. Uncrewed Aircraft1 (UA) are, by definition, an aircraft with no pilot(s) on board. These aircraft can be remotely controlled or can be operated using autonomous technology. Many new ideas and technologies are initially developed, tested and used in military forces prior to becoming available to civilians; UA are no exception. The first pilotless aircraft were invented during World War I:

- In 1917, the British military flew what was called the Aerial Target; and

- In 1918, the United States military flew the Kettering Bug (Vyas, 2020).

In 2006 the FAA created the Unmanned Aircraft Program Office with the goal of integrating commercial UAS use into the National Airspace System (NAS) (FAA, 2006). Leading into fall 2016, 13 permits had been approved by the FAA for commercial UAS operators. This drastically changed in 2016 with the creation of 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 107 – Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems. The FAA began issuing thousands of permits each year following the passage of this new regulation (Alkobi, 2019). The FAA’s vision and approach for UAS and other AAM disrupters for the coming years was released in June of 2020 within the Concept of Operations for UAM 1.0 document. In September 2022, the FAA also issued interim guidance via Engineering Brief Number 105 on vertiport design.

The 14 CFR § 107 – Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems regulations define small UAS as any aircraft that weighs 55 pounds or less at takeoff, including the aircraft itself and its payload. These regulations outline the requirements of small UAS registration, remote pilot certification requirements and all operational and safety regulations associated with UAS flight. Although restrictions do exist within the current UAS rules, the passing of the 14 CFR § 107 regulation enabled tremendous growth in both commercial use and recreational use of drones. As of February 1, 2023, the FAA reported 871,984 UAS registered in the United States and 307,049 Certified Remote Pilots (Federal Aviation Administration, 2023a).

Current UAS Use Cases

UAS have seen a surge in applications in recent years, driven by advancements in technology, declining costs and proof of utility (Banks et al., 2018). The versatility of UAS has made them suitable for a wide range of applications, including aerial photography and videography, goods delivery, search and rescue operations, infrastructure inspections, agricultural applications, and environmental monitoring.

The transportation sector is one area in which UAS has seen significant growth. State DOTs are utilizing UAS to gather data and improve the efficiency of their operations. In 2018, 20 State DOTs were using UAS; in 2022, all State DOTs self-reported the use of UAS (AASHTO, 2019). State DOTs are using UAS across multiple use cases, such as inspecting bridges, roads, and other infrastructure, which reduces the need for manual inspections and reduces the risk to workers. UAS can also be used to survey roadways for traffic patterns, assess the impact of natural disasters on transportation networks, and support

___________________

1 The term “unmanned aircraft systems” is transitioning to the gender-neutral term “uncrewed aircraft systems” to reflect the increasing use of these systems in a variety of industries, and to ensure that language is inclusive. The primary term used throughout this document is “uncrewed” except when directly referring to official offices or regulations which still employ the term “unmanned”.

planning and design activities. Hubbard and Hubbard highlight over 40 reported use cases across State DOTs throughout the United States (2020).

In addition to improving operational efficiency, UAS are also being used by State DOTs to enhance safety. For instance, UAS can be used to inspect hard-to-reach areas, such as high bridges or steep slopes, reducing the risk to workers who would otherwise have to climb to these areas. UAS can also be used to monitor construction sites, ensure workers are following safety protocols and to monitor traffic in real time, providing time sensitive information to drivers and first responders. The growth of UAS applications in the transportation sector is just one example of how this technology is transforming a wide range of industries.

The FHWA has been supporting State DOTs’ adoption of UAS technologies through the Every Day Counts (EDC)-5 Initiative. The initiative has helped State DOTs utilize UAS in their operations by providing guidance, resources and funding opportunities. For example, the initiative has published peer exchange reports and technical briefs and has developed other training materials such as webinars and online modules. These resources have been developed to help State DOTs understand the benefits and limitations of UAS technology, as well as the regulations and policies governing its use.

The EDC-5 Initiative has also facilitated collaboration between State DOTs and other stakeholders, including UAS manufacturers, service providers, academic institutions and local agencies. These collaborative events have taken place in the form of peer exchanges and workshops. This has helped State DOTs access the latest UAS technology and share knowledge and experience with other DOTs. The results of these collaborative efforts have helped State DOTs make informed decisions about incorporating UAS into their operations, improving their efficiency and effectiveness.

Future UAS Use Cases and Opportunities

The widespread adoption of UAS across transportation agencies has led numerous agencies to explore what other technologies can be used together with UAS. One example is the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) technologies to help process UAS-collected data by automating and optimizing various data analysis tasks. ML algorithms can be trained to recognize patterns in large datasets and make predictions based on the data, which reduces the manual effort required to process and analyze the data.

One example comes from a collaborative effort between the Colorado DOT and researchers at Colorado State University. The researchers created and tested an AI data processing module that can automatically perform a variety of tasks when given UAS bridge inspection data. The AI-powered data processing algorithms can quickly identify areas of interest and extract meaningful insights, such as the type, location, and details of infrastructure defects. The AI can also produce three-dimensional (3D) models and georeferenced, elementwise as-built bridge information models where the structure and its identified defects can be visualized and documented (Perry et al., 2020). Using these technologies allows organizations to not only efficiently collect the data, but also to proficiently process the data to produce impactful data models. This, in turn, enables organizations to make data-driven decisions faster and with greater accuracy.

Another emerging use case for UAS that will not reach full potential until enabled by BVLOS regulations is drone-in-a-box solutions. Drone-in-a-box is the industry term given to describe a type of autonomous UAS technology that consists of the aircraft, a weatherproof container and the operating system.

Together, these components are capable of autonomously launching the UAS, completing the mission and returning to the housing system without human intervention. This technology can be used across a variety of applications and is useful when regular and repeatable operations or inspections are needed, especially in remote areas.

In March 2022, the UAS BVLOS Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) released its final report summarizing recommendations for the FAA on how to advance BVLOS operations. The report acknowledged that the current regulations do not reflect the capabilities or maturity of UAS technologies. The rulemaking committee noted that the current restriction of UAS operations to be within line of sight is one of the biggest constraints to UAS technology scaling and maximizing “societal and economic benefits for the American public” (UAS BVLOS ARC Final Report, 2022).

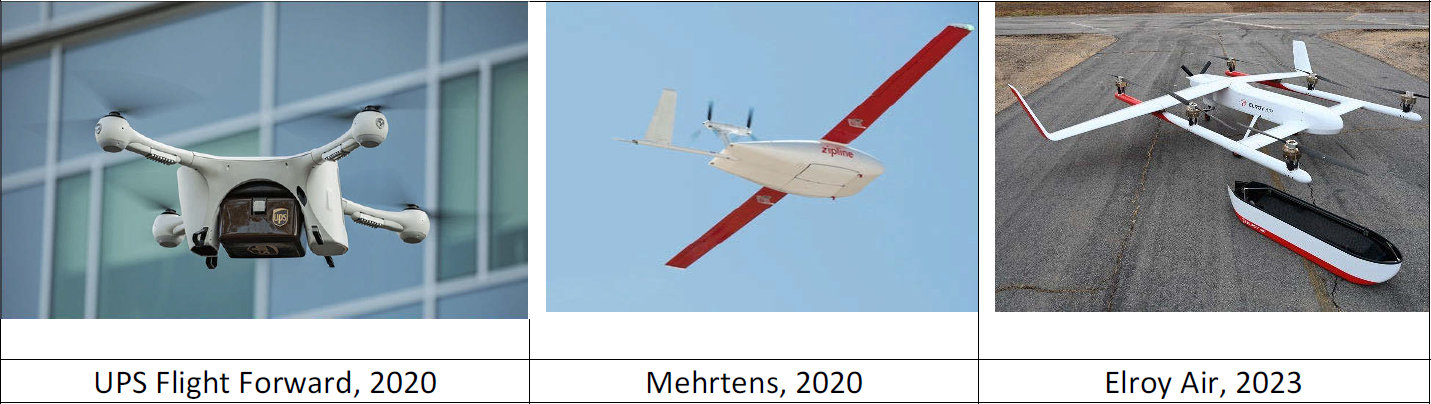

UAS package delivery presents another growing UAS use case with the potential of large-scale future operations. In the Spring of 2022, it was estimated that more than 2,000 UAS package deliveries were happening daily throughout the world (Cornell et al., 2023). On April 19, 2019, a UAS was used to deliver the first human organ for transplant in Baltimore, Maryland (Coffey, 2019). Zipline is an example of a leading UAS package delivery company. In 2016, Zipline began operating in Rwanda by delivering blood and other medical supplies. In May 2020, Zipline partnered with Novant Health and begin delivering COVID-19 vaccines and supplies in North Carolina (Mehrtens, 2020). In October 2022, Zipline began UAS deliveries of prescription medications to Intermountain Healthcare customers in Salt Lake County, Utah (Zipline – Instant Logistics, 2022). As of February 2023, Zipline has completed 522,020 commercial deliveries with UAS across its global operation (Zipline – Instant Logistics, 2023).

Currently, most UAS package deliveries are executed by small aircraft which, typically, transport packages weighing less than 5 pounds. But there are larger UAS in various stages of development, testing and certification. For example, Elroy Air’s Chaparral aircraft can autonomously deliver up to 500 pounds of cargo across a 300-mile range. The Chaparral is designed to operate as a larger system; the aircraft is capable of disconnecting from the cargo pod and autonomously positioning and connecting to the next loaded cargo pod for the next operation. Figure 11 depicts examples of small and large UAS for package delivery.

The FAA has supported these UAS innovations and is working with state, local and tribal governments, as well as with industry to enable emerging use cases. For example, the FAA created a regulatory path for large-scale commercial operations of UAS package delivery services through Title 14 of the CFR § 135 air carrier certification. As of February 2023, the FAA has issued four standard Part 135 air carrier

certificates to companies operating UAS package delivery services (Federal Aviation Administration, 2022b).

Advanced Air Mobility (AAM)

The term AAM is an inclusive umbrella term that encompasses new enabling technologies that allow for new air transport use cases.

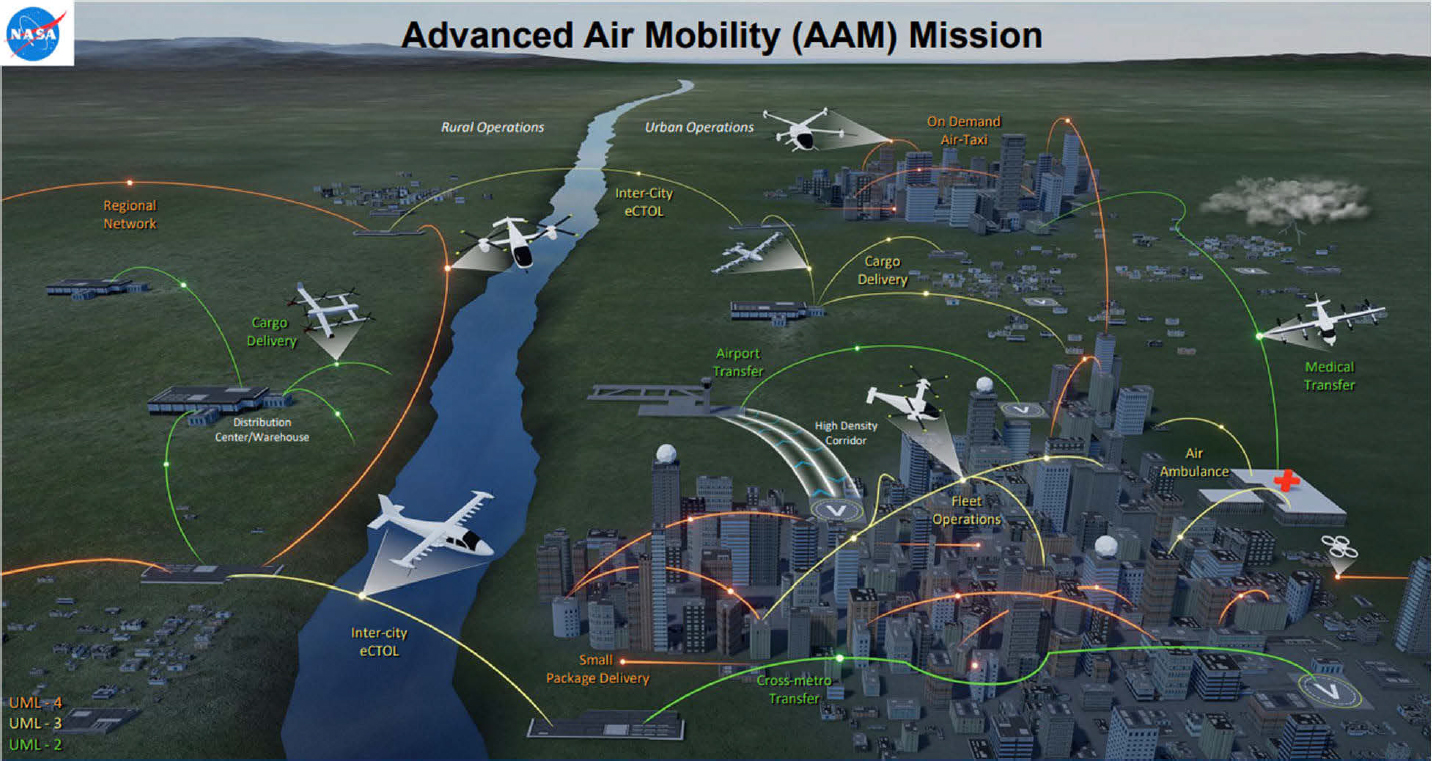

“NASA’s vision for Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Mission is to help emerging aviation markets to safely develop an air transportation system that moves people and cargo between places previously not served or underserved by aviation – local, regional, intraregional, urban – using revolutionary new aircraft that are only just now becoming possible. AAM includes NASA’s work on Urban Air Mobility (UAM) and will provide substantial benefit to U.S. industry and the public.” – NASA, March 2020

AAM encompasses a variety of use cases for electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft and electric or hybrid-electric aircraft performing short takeoffs and landings (STOL). AAM is inclusive of UAS cargo delivery (small and large) outlined in the above section, UAM, Regional Air Mobility (RAM), and other use cases, such as air ambulance, medical transport, and emergency response.

UAM is a subset of AAM and is defined by the FAA as “a safe and efficient aviation transportation system that will use highly automated aircraft that will operate and transport passengers or cargo at lower altitudes within urban and suburban areas” (FAA, 2022a). Although UAM refers to air transportation within an urban environment, RAM refers to the larger regional connectivity potential and the ability to connect rural areas to urban economic engines. In 2016 the Vertical Flight Society began tracking AAM aircraft from the concept phase through development, testing and certification phases (eVTOL News, 2023). There are hundreds of aircraft at various points along the path of development, but Table 1 outlines some leading examples of aircraft and the potential use cases.

Table 6: Examples of AAM aircraft with associated use cases and operational capabilities

| Company/Aircraft | Potential Use Case | Number of Passengers/Cargo Capacity | Anticipated Range | Anticipated Speed | Anticipated Service Entrance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Joby Aviation S4 |

Air Taxi | 4 | 150+ miles | 200 MPH | 2024 | Joby Aviation, 2022 |

Archer Aviation |

Air Taxi | 4 | 60 miles | 150 MPH | 2024 | Archer, 2022 |

Beta ALIA-250 |

Cargo/Air Taxi | 200 Ft ^3 or 5 | 250 miles | 175 MPH | 2025 | Beta, 2023 |

Eviation Alice |

Cargo/Regio-nal Passenger Operations | 450 Ft ^3 or 9 | 500+ miles | 250 KTS | 2027 | Eviation, 2022 |

Heart Aerospace ES-19 |

Regional Passenger Operations/Cargo | 19 | 250 miles | 180 KTS | 2026 | Heart Aerospace, 2022 |

AAM Use Cases and Opportunities

In 2018, NASA commissioned two pioneering market studies of potential AAM use cases, including last-mile drone package delivery, air metro service which resembled current transit options like subways where there would be pre-set routes and stops (average of three passengers per trip), air taxi service (average of one passenger per trip), airport shuttle service and air ambulance. The viability levels of these potential use cases varies based on technology, location, existing regulations, market demand and other factors. Since these initial NASA studies, a variety of other organizations and companies have completed studies outlining potential AAM use cases and opportunities. This rendering (Figure 12) was shared at the inaugural meeting of the NASA AAM Working Groups to show different AAM use cases that could exist in the ecosystem.

UAS AND AAM LEGISLATION

As UAS use cases increase and AAM aircraft become certified and begin operations, state and local regulatory bodies are engaging in creating more laws to assist with safe and secure integration of these technologies. In recent years the number of states creating laws to address UAS and AAM-related topics has started to grow, 44 states have enacted UAS-related laws since 2013 (state Unmanned Aircraft System Legislation, 2022). Table 7 outlines the states and their related UAS/AAM laws passed in the last two legislative sessions.

Table 7: Overview of State Legislation for UAS or AAM-Related Activities

| State | Bill | Details |

|---|---|---|

| AK | HB281, SB162 | University of Alaska Drone Program: $10M (Critical Minerals and Rare Earth Elements); $7.8M (Research and Development Heavy Oil Recovery Method); $5M Research and Development. |

| AL | HB21, SB17 | Critical infrastructure, provides further for crime of unauthorized entry of a critical infrastructure, including UAS, provides additional penalties. |

| AR | SB173 | Prohibits UAS operations over food processing, manufacturing, and correctional facilities. |

| CA | AB481 | Requires law enforcement agencies to obtain approval from local legislative bodies to use military equipment, including UAS. |

| FL | HB659 | Exempts certain government agencies that are non-law enforcement agencies from laws prohibiting the use of UAS related to managing invasive plants and animals. |

| FL | HB5001 | Appropriates $14M for industry training and certification, including UAS. Provides $400,000 for UAS to be used locating intrusive snakes. |

| FL | SB44 | Allows law enforcement agencies to use UAS for additional use cases. Requires a list of approved drone manufacturers to be published on the state Department of Management Services website. |

| ID | HB486 | Allows law enforcement and other government agencies to use UAS to assist in accident investigations, crowd management, natural disaster assessments, training, and following the delivery of a search warrant. |

| IN | HB1227 | Legislation that notes using unmanned aerial vehicles is not a defense for avoiding prosecution for being “within 1,000 feet of a school.” |

| KS | SB444 | Bill that defines UAS as under the jurisdiction of “aviation only - no limit.” |

| KY | HB346 | Prohibits federal, state, and local law enforcement agency from obtaining in-person or drone access to private lands for inspection, visit, surveillance, or installation of surveillance devices without probable cause, warrant, or consent. |

| LA | HB587 | Creates the Louisiana Drone Authority Committee under the DOT to provide recommendations on policies and regulations related to adopting UAS. Notes state laws should align with federal control of airspace. |

| MA | HB4183 | No person shall operate a small, UAS within a vertical distance of 400 feet in a school zone without authorization by the superintendent of schools. |

| MA | HB5164 | Provides $25,000 to study wildlife using traditional aviation or the use of UAS. |

| MA | HB4002 | Appropriates $100,000 for marsh restoration, including the use of UAS for mapping efforts. |

| MD | SB600, HB670 | Prohibits law enforcement agencies from receiving specific UAS equipment from a federal surplus program. |

| MI | SB796 | Restricts county, village, or township from enacting or adopting ordinance policies that relate to the ownership or operation of AAM aircraft Restricts their power in regulating as well. |

| MN | SF3258 | Prohibits UAS operations over correctional facilities or land controlled by such a facility. |

| MN | SF3072 | Allows law enforcement agencies to use UAS for emergency situations involving death or bodily harm, public events where there is a risk to safety or reasonable suspicion of a crime, counter-terrorism threat assessments, accident investigation, training, public relations, and to prevent loss of life or property in natural disasters. |

| MN | SF3148, HF3219 | Requires state registration of UAS for $25 unless it is owned/operated for recreational purposes. Must report registration proof to the state. There are misdemeanor penalties for not registering or operating while unregistered. |

| MO | HB1619 | Prohibits the use of a drone or unmanned aircraft to photograph, film, videotape, create an image, or livestream another person or personal property of another person, with exceptions. |

| MO | HB1963 | Makes it a criminal offense to operate a UAS near a correctional facility, mental health facility, open-air stadiums with 5,000 or more seats, without written consent. |

| MS | HB259 | Prohibits any person from using an unmanned airborne device to capture unauthorized images without consent. Each image captured is a separate offense. |

| MS | HB1383 | An act to prohibit an individual from operating small, unmanned aircraft unless it has been registered with the Criminal Information Center of Department of Public Safety. |

| MS | HB1517 | Provides $16M dollars for horizon-thinking programs such as advanced manufacturing, drone, electric vehicle, fiber, data analytics, and management. |

| MS | HB974 | Creates the Mississippi Unmanned Aircraft Systems Protection Act of 2021 that shall not prohibit UAS operations by law enforcement agencies for any lawful purpose in the state. Outlines penalties for the misuse of UAS. |

| NC | SB105 | Requires an annual legislative report regarding UAS. |

| NJ | SB2022 | Appropriates $500,000 for an aeronautics UAS program. |

| NJ | S451 | Restricts the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) to conduct surveillance, gather evidence, or any other law enforcement activity unless warrant, emergency, probable cause, written consent. |

| NJ | A3174, S2297 | Requires certain drones to contain geo-fencing tech. Makes violation a fourth-degree crime. Every drone sold or operated in the state shall contain geo-fencing tech that prevents UAS from operating above 500 feet when within 2 miles of an airport, protected airspace. |

| NY | S3602 | Requires registration of general aviation aircraft; aircraft used for civil aviation; issuance of certificates of registration; proof of insurance. |

| NY | S675 | Imposes limitations on the use of drones for law enforcement and singles out drones. |

| NY | A417 | Prohibits police from using unmanned aircraft to gather, store, or collect evidence of any type for criminal conduct unless a valid search warrant was first obtained. |

| OH | 2409 | Ownership of the airspace above a parcel of property in this state is vested in the owner of that parcel. Allows for ownership above the legal limit. |

| OK | HB3171 | New section of law to be codified in Oklahoma Statutes stating no person using UAS/drone can trespass with intent, install photographs, videos, etc. without consent; intentionally use drone to surveillance; land drone on lands or waters of another resident without consent. |

| OK | SB659 | Establishes the Oklahoma Aeronautics Commission to serve as the agency to research, develop, and support the adoption of UAS by various state agencies. |

| OR | SB315 | Exempts information that would create competitive disadvantages for UAS owners or users. |

| OR | SB5506 | Appropriates $15M to the Boardman Tactical UAV Facility. |

| RI | H7787 | Establishes regulations to reduce hazardous emissions. |

| SD | HB1059 | Makes it a criminal offense to operate UAS that are not in full compliance with FAA regulations. |

| SD | HB1065, SB74 | Prohibits the use of UAS to photograph, record, or observe another person in a private place or to land on private property. Exceptions are government agencies or emergency management operations. |

| TN | SB258, HB924 | Outlines additional circumstances in which law enforcement agencies can use UAS without a search warrant. Increases the number of days from 3 to 30 regarding data storage of potential evidence. |

| TX | HB1758 | Requires law enforcement agencies using UAS to adopt certain policies and file a report with the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement every 2 years. |

| TX | SB149 | Prohibits a drone from flying over a public or private airport depicted in any current FAA aeronautical chart or any military installations. |

| UT | HB259 | Amends provisions related to use of an UAS to apply to the use of an imaging surveillance device in conjunction with UAS. Prohibits police from obtaining data unless in good practices. |

| UT | SB68 | Criminal penalties for trespassing. Includes section about UA that includes unlawful entry, flying over private property, reckless, fear of others’ safety from "unmanned aircraft's presence," and unauthorized flying on any portion of private property. |

| UT | SB122 | Provides the ability to be found guilty of a criminal offense that is committed with the aid of an UAS. |

| UT | SB166 | Restricts a political subdivision or entity within the subdivision from enacting law, ordinance, or rule governing the private use of an unmanned or AAM unless authorized by this chapter or an airport operator has authority. |

| VA | SB1098 | Provides UAS owners’ exemptions regarding state aircraft registration. |

| VA | HB742 | Empowers localities to regulate the takeoff or landing of UAS on property owned by said localities. Requires ordinances or regulations developed by the localities must be reported to the district attorney’s office. |

| VA | HB1017 | Requires an annual state assessment of current and future initiatives related to UAS. |

| VA | HB30 | Appropriates $2M over 2 years to the Virginia Center for Unmanned Systems to serve as a catalyst for UAS growth in the state. Requires the center to begin industry and business collaboration. |

| VT | SB124 | Prohibits law enforcement using facial recognition unless it is for operations related to search and rescue or assessment of natural disasters. |

| WA | HB1470 | Intends to extend certain aerospace industry tax preferences to commercial UAS manufacturing in order to encourage the migration of these businesses to Washington, in turn creating and retaining good wage jobs and new tax revenue for the state. |

| WA | HB1054 | Prohibits law enforcement agencies from acquiring or using armed or armored drones. Any agency that currently owns such equipment must return it to the federal program from which it was acquired or destroy it. |

| WI | SB237 | Permits a person to operate a drone over state facilities if prior written authorization is obtained. |

| WV | SB5, HB4667 | Aims to create West Virginia Unmanned Advisory Council. Includes privacy and video legislation, restrictions on flying, harassment, property issues. |

| WV | HB2760 | Expands tax credit availability to drone manufacturers. |

| WY | HB128 | Except as otherwise permitted by law, a person is guilty of criminal trespass by drone if he causes a drone to fly 200 feet or lower over the private land or residence of another person without authorization. |

Source: State UAS Legislation (2022)

UAS and AAM Obstacles

State DOTs often experience similar obstacles to integrating UAS across operations. It can be challenging to earn leadership support for the initial purchase of UAS, remote sensors and other equipment. Once UAS have been purchased, it can be difficult to secure an ongoing budget to support UAS maintenance, fleet renewal, personnel training and other associated UAS program costs. Other obstacles can be a lack of workforce, high turnover rates, or keeping up with rapidly evolving technology on a limited budget. These challenges can prohibit an organization’s ability to mature a UAS program and maximize the return on investment alongside other benefits.

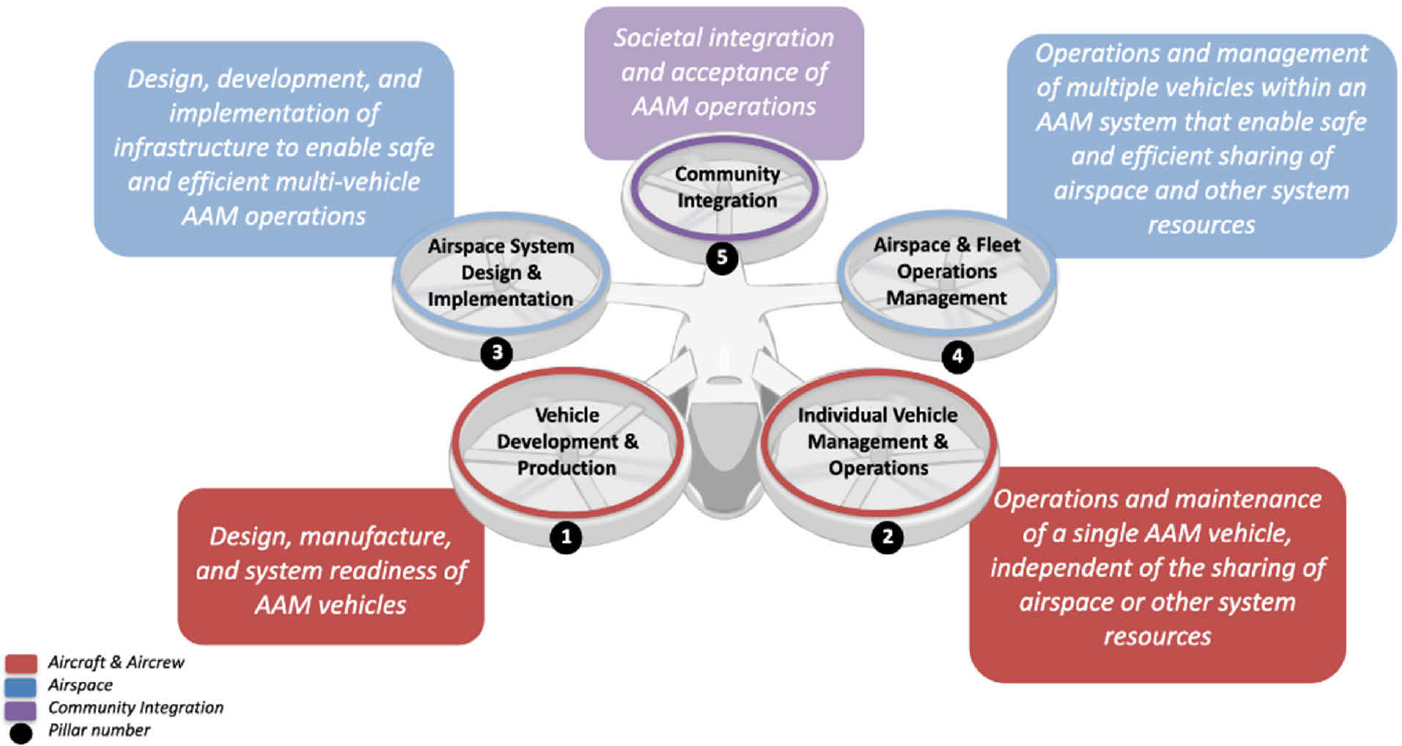

Several obstacles stand in the way of achieving the evolving and future use cases for UAS and other AAM aircraft as outlined in previous sections. NASA has been actively involved in leading research efforts and cross-organization collaboration to advance AAM. NASA established the AAM Ecosystem Working Groups in early 2020 to bring together federal agencies, industry, and academia to work on

overcoming obstacles to AAM integration. NASA’s framework for addressing obstacle categories is depicted in Figure 13.

Each of these high-level categories of barriers to UAS and AAM integration contains a host of questions to be answered and problems to be solved. Although approaching each of these is beyond the scope of this literature review, the following obstacles have been identified for a thorough analysis throughout various stages of this project:

- UTM key stakeholder roles

- Cross-jurisdictional collaboration

- Funding resources

- Workforce development

UTM

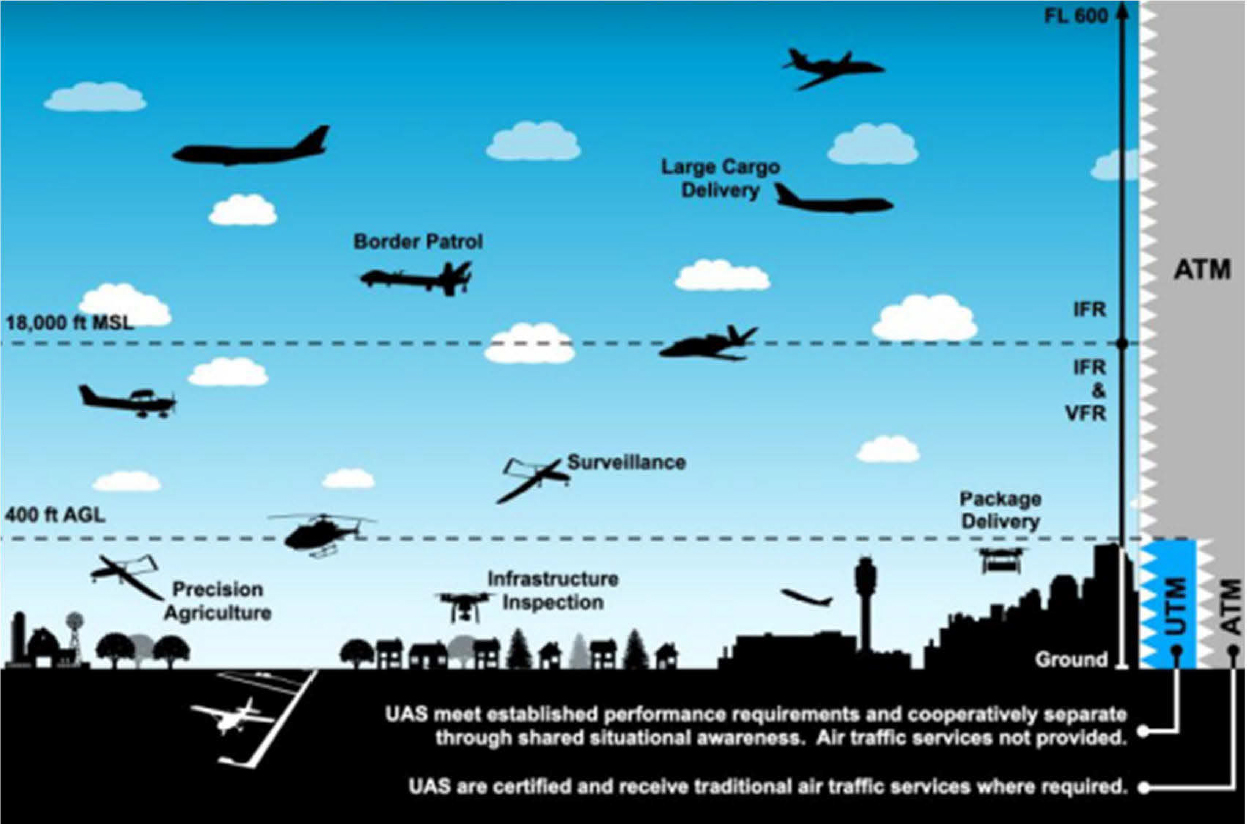

In 2018, the FAA released version 1.0 of the Concept of Operations (ConOps) for Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Traffic Management (UTM). In March 2020, the original document was updated to the UTM ConOps version 2.0. This document defines UTM as “the manner in which the FAA will support operations for UAS operating in low altitude airspace” (Federal Aviation Administration, 2020). The FAA recognizes the tremendous growth and opportunities presented by UAS and AAM technologies. The regulatory agency also recognizes that projected UAS/AAM operations extend beyond the capabilities of the existing Air Traffic Management (ATM) system and acknowledges that a concept for UTM must be developed and matured (FAA, 2020).

The FAA ConOps V2 document is focused on UAS operations 400 feet above ground level or below. Figure 14 is from the ConOps document and provides the operational context of UTM services. Although this document provides detail regarding the potential framework of UTM for operations below 400 feet,

numerous organizations are conducting the necessary research to solve the complex issue of UAS and AAM operations scaling to full potential within the existing NAS.

Key Stakeholder Roles

Numerous stakeholders will need to work collaboratively to achieve the integration of UAS and AAM. At a high level, these stakeholder groups include government agencies, planning organizations, industry, academia, and communities. Each of these groups comprises multiple levels; for example, government agencies at the federal, state, and local levels will be key to AAM integration. Some organizations have explicitly or implicitly defined the role they will play, but others are just beginning to explore the potential of UAS and AAM use cases. As related to the scope of this project, this section will focus on stakeholder roles at the federal, state, and local levels.

Federal Role

The FAA’s mission is to “provide the safest, most efficient aerospace system in the world” (Federal Aviation Administration, 2023b). The FAA will continue to execute this role as the uses of UAS increase and AAM aircraft enter the market. The FAA is the gatekeeper of safety and will ensure the next generation of aircraft meets the highest level of safety through the certification and regulation of the aircraft, the operating framework, and the infrastructure (FAA, 2022c). The FAA has been progressing these efforts under existing regulations wherever possible and by making adjustments, as needed. For example, in December 2022 the agency published in the Federal Register a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) titled “Updated to Air Carrier Definitions” – this NPRM included changing regulatory definitions to include “powered-lift” aircraft such as electric VTOL aircraft (FAA, 2022d).

NASA’s vision for AAM outlines the agency’s role of helping emerging markets be achieved in a safe and sustainable way. NASA fulfills this role by partnering with industry and providing resources to assist in the development and testing of aircraft, airspace simulation software, infrastructure, automation systems and many other supporting systems. NASA creates various platforms of collaboration with key stakeholder groups, such as the establishment of the AAM Working Groups. NASA announced another example in spring 2021, when the agency signed agreements with five state and local government entities to work together to establish how “emerging cargo carrying drones and passenger carrying air taxi services can best be included in their civic transportation plans” (Banke, 2021).

In February 2023, NASA published its compilation of resources and interviews with subject matter experts in the form of an AAM Playbook. The playbook shares information related to air taxis, drone package delivery, and drone medical and emergency services. It covers topics such as emergency response, health care, automation, vertiports, travel time, airspace, noise, ride quality, accessibility, cargo deliveries and safety (Whiting, 2023).

State Role

In May 2022, the AASHTO Journal published an article outlining AASHTO’s support of the Advanced Aviation Infrastructure Modernization bill, which would create a $25 million grant fund for state, local and tribal agencies to use for planning AAM infrastructure (AASHTO, 2022). Although this bill was not enacted into law, the support offered by transportation agencies expressed the need for resources to plan for this new mode of transportation and delivery services. Although some states’ agencies may be unsure of the role they may have, other states are moving forward.

The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) published numerous resources and documents related to AAM on its website, including its AAM Roadmap Report completed in June 2022 (FDOT, 2022a). FDOT oversees and maintains the Florida Aviation System Plan (FASP), a long-term planning tool for the state’s aviation system. To support the future update of the FASP, FDOT created the interim AAM policy framework and roadmap report (FDOT, 2022b). FDOT also outlined its role in vertiport site approval and licensing in accordance with Florida Statute 330.30 (FDOT, 2022b).

The Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) published its Ohio AAM Framework report in August 2022. This report outlines AAM ecosystem components, such as vehicles, ATM, federal agency oversight, use cases, route framework and infrastructure. The study also explored use cases and the potential impacts in Ohio; use cases explored were on-demand air taxis, RAM, airport shuttle services, emergency services, corporate aviation and cargo deliveries. The report outlines the roles ODOT perceives other stakeholder groups have and defined the role that ODOT sees for itself, which includes digital and physical infrastructure investment, policy and rulemaking, public outreach and education, and workforce and economic development (Judson et al., 2022).

The Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) is another State DOT that has leaned into leading AAM efforts at the state level. In December 2022, UDOT published the Utah AAM Infrastructure Study. This study provided an analysis of assets throughout the state that can be used to support AAM operations and the creation of an aerial transit corridor transportation system. The report also presented a phased approach and plan to facilitate the integration of a statewide multimodal transportation system. The comprehensive study explored a variety of topics in detail, including use cases and their impacts, aerial corridor and route planning, infrastructure needs, regulatory needs at state and city levels, funding and

investment strategies, minimum standards, and community and stakeholder engagement (Wheeler et al., 2022).

In addition to this study, UDOT brought drone package delivery services to the state of Utah, not as a research and testing site, but as an actual service direct to consumers. Zipline and Intermountain Healthcare launched services in October 2022 to enable customers to receive prescription medications and other medical supplies directly at their homes via drone delivery (McNabb, 2022). And in January 2023 DroneUp and Walmart began its drone delivery services at two separate locations within the state (Kesteloo, 2023).

Local Role

Although city lawmakers and agencies typically do not actively regulate legacy aviation, they likely have a role to play in the use of UAS and AAM aircraft. Many cities may be unaware of or in the beginning stages of understanding the potential of UAS and AAM capabilities, but some cities have embraced the technologies. For example, Orlando is the only municipality to be selected for participation in NASA’s government entities collaboration, and the city is also one of the founding members of the World Economic Forum’s Advanced and Urban Aerial Mobility Cities and Regions Coalition (Coulon, 2023). Orlando has facilitated city and regional stakeholder collaboration to prepare for the integration of AAM and UAS technologies.

Los Angeles is another city at the forefront of leading various city agencies to work together to ensure a safe, efficient, equitable, sustainable and modern transportation system for all city residents and businesses (Los Angeles Department of Transportation, 2021). Los Angeles is committed to taking a comprehensive and active approach to planning, regulating and enforcing an equitable and safe integration of UAS and AAM services.

In conclusion, federal agencies such as the FAA and NASA have clearly defined roles to play, and some states and cities are playing a leading role at their level. Yet, many unknowns still exist regarding stakeholder roles. For example, research and knowledge gaps persist around the roles that State DOTs should play in the integration of UAS and AAM products and services. These gaps include questions a concerning whether State DOTs should be given regulatory authority or just general oversight; whether state DOT budgets should be used to fund UAS and AAM-related infrastructure, or whether State DOTs’ roles are limited as the regulation and use of aircraft and airspace is largely a federal responsibility.

Cross-Jurisdictional Collaboration

Due to the challenges of maturing UAS uses and complexity of AAM integration, cross-jurisdictional collaboration will be key to overall success. Stakeholders can learn from other past efforts on the best approach to establishing and maintaining cross-jurisdictional collaboration. The FHWA sponsored a workshop held in February 2018 titled “Multi-Jurisdictional Coordination for the Great Lakes Region” – this workshop hosted public and private decision-makers to coordinate efforts regarding multimodal freight transportation and emerging technologies. The workshop’s final report outlined lessons learned, best practices, opportunities and challenges related to how multiple jurisdictions can collaborate continually to meet a region’s needs and goals (Denbow, 2018).

The American Society for Public Administration offers resources and an overall framework on how cities can work together across multiple topics. These resources outline common difficulties and concerns that

cities may have when initially establishing collaborative efforts, as well as solutions to those difficulties and concerns, and identifies the advantages of ongoing cross jurisdiction participation (McGimpsey, 2019). Organizations such as the Community Air Mobility Initiative offer services to help cities and states begin collaboration and preparations for UAS and AAM specific operations. These resources are identified in the literature review, but a literature gap remains regarding how states and cities are completing cross-jurisdictional collaboration directly related to integrating UAS and AAM.

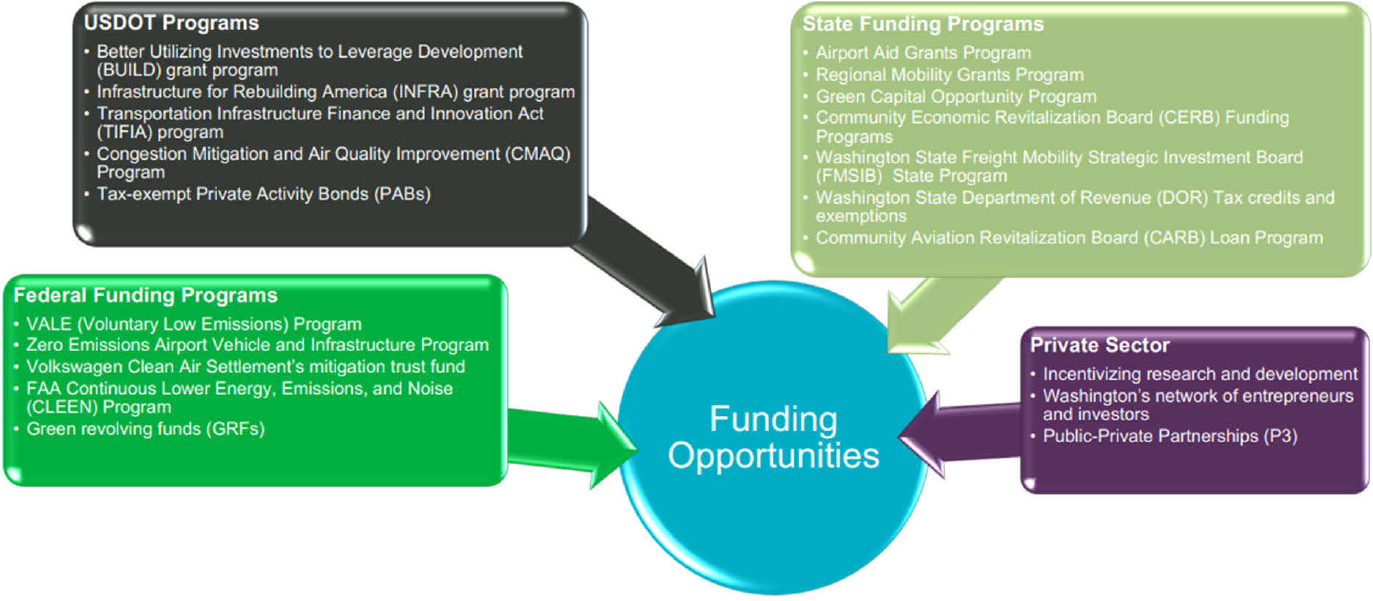

Funding Resources

State DOTs often use year-end money or grants to begin internal UAS programs but securing ongoing funding is often a challenge. Some funding resources are outlined below, but a research gap persists on the most common UAS funding options and how State DOTs can achieve a dedicated UAS budget. One known potential funding source is the FHWA State Transportation Innovation Council (STIC) incentive program, which encourages a culture of innovation and utilizing the latest technologies, such as UAS (FHWA, 2022). Another potential grant program is the SMART program, which received $100 million per fiscal year through 2026 (U.S. Department of Transportation, n.d.).

Aside from State DOTs UAS programs, considerable funding will be needed to support the digital and physical infrastructure of UAS and AAM aircraft. Some federal lawmakers recognize the need for additional funding and introduced two UAS and AAM-related funding bills in 2022: the Advanced Aviation Infrastructure Modernization Act, which would have provided $25 million over two fiscal years, and the Drone Infrastructure Inspection Grant Act, which would have provided $100 million over two fiscal years. Both bills passed the United States House of Representatives but did not pass the United States Senate (U.S. HR5315, 2023).

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, otherwise known as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, provided what has become known as a once-in-a-generation investment of over $550 billion into nation’s infrastructure (The White House, 2021). This law provided agencies such as the FAA and FHWA with ongoing funding that may be used toward UAS or AAM infrastructure in the future. The Washington Electric Aircraft Feasibility Study outlined other potential funding opportunities for AAM aircraft, which are summarized in Figure 15.

Workforce Development

Workforce development is defined as “the coordination of public and private-sector policies and programs that provides individuals with the opportunity for a sustainable livelihood and helps organizations achieve exemplary goals, consistent with the societal context” (Jacobs & Hawley, 2009). Given that many State DOTs are struggling to retain their current workforce, coordinating efforts to build sustainable pipelines for future workforce presents a significant challenge. In January of 2021 the Vertical Flight Society held a panel of academia, industry, and military representatives to discuss the ongoing challenge of workforce development for the aerospace and aviation industries. The overall aviation and STEM workforce pipeline must be strengthened for UAS technologies to mature and AAM operations to become a reality (Creedy, 2021).

The National Center for the Advancement of Aviation Act sought to create a center for collaboration to strengthen the aviation industry and workforce development efforts. This proposed bill has failed to pass for several years in a row (H.R. 3482, 2023). The Aerospace Education Program Alliance is the private sector’s recent attempt to accomplish a similar mission of connecting education programs and building a stronger workforce pipeline (Aerospace Education Program Alliance, 2023). Various efforts are in the works, but much remains to be learned about successful workforce development strategies specific to key stakeholder groups for maturing UAS and AAM operational capabilities. The collective efforts and associated curriculum being used to prepare students for careers related to UAS and AAM is also unknown.

Conclusion

The utilization of UAS is widespread and continues to mature with the advancement of UAS technologies and adoption of enabling regulations. UAS fits into the broader AAM ecosystem, which also includes UAM and RAM. Together, these technologies offer a variety of use cases that have the potential to improve people’s lives. Federal agencies such as the FAA and NASA are thoroughly engaged in numerous efforts to integrate AAM into the National Airspace System and into the overall transportation ecosystem. Many obstacles must be overcome to implement UAS and AAM capabilities, and this comprehensive literature review identified the following knowledge gaps:

- Current maturity levels of State DOTs UAS programs

- The roles and responsibilities of state and local transportation agencies regarding implementation of UAS and AAM services

- How the industry perceives the role state and city transportation agencies should play

- Current status and overall best practices for cross-jurisdictional collaboration directly related to UAS and AAM activities

- Funding opportunities and strategies to secure ongoing funding to support UAS programs and AAM initiatives

- Strategies to strengthen and grow the UAS and AAM workforce pipeline

- Details around current educational programs and curriculum to prepare youth for UAS/AAM careers

The research team will engage a diverse group of stakeholders using a survey instrument to address these identified knowledge gaps. The research team will use these identified gaps to inform the survey questions and the survey recipient list.

References

AASHTO. (2019, May). AASHTO UAS/Drone Survey of All 50 State DOTs. Uncrewed Aerial Systems/Advanced Air Mobility. Retrieved from https://uas-aam.transportation.org/aashto-research/

Aerospace Education Program Alliance. (2023). About Us. https://aerospaceeducationprogramalliance.org/about

Alkobi, J. (2019, January 15). The Evolution of Drones: From Military to Hobby & Commercial. Percepto. https://percepto.co/the-evolution-of-drones-from-military-to-hobby-commercial/

Banke, J. (2021, May 14). NASA to Help Local Governments Plan for Advanced Air Mobility. https://www.nasa.gov/aeroresearch/programs/iasp/aam/nasa-to-help-local-governments-plan-for-advanced-air-mobility

Banks, E., Cook, S., Fredrick, G., Gill, S., Gray, J., Larue, T., Milton, J., Tootle, A., Wheeler, P., Snyder, P., & Waller, Z. (2018, July). Successful Approaches for the Use of Unmanned Aerial System by Surface Transportation Agencies – Domestic Scan 17-01. https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/docs/NCHRP20-68A_17-01.pdf

Coffey, B. (2019, April 26). Special Delivery: For The First Time, Drone Flies Kidney To Patient For Successful Transplant. General Electric News. https://www.ge.com/news/reports/special-delivery-first-time-drone-flies-donor-kidney-patient-successful-transplant#:~:text=A%20medical%20and%20aviation%20breakthrough,human%20kidney%20from%20Baltimore's%20St

Coulon, J. (2023). Advanced Air Mobility. https://www.orlando.gov/Our-Government/Orlando-plans-for-a-future-ready-city/Advanced-Air-Mobility

Cornell, A., B. Kloss, D.J. Presser, R. Riedel. (2023, January 3). Drones take to the sky, potentially disrupting last-mile delivery. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/aerospace-and-defense/our-insights/future-air-mobility-blog/drones-take-to-the-sky-potentially-disrupting-last-mile-delivery

Creedy, K. (2021, February 16). Industry, Academia Must Break Down Silos to Develop Future Workforce. https://futureaviationaerospaceworkforce.com/2021/02/16/industry-academia-must-break-down-silos-to-develop-future-workforce/

Elroy Air. (2023). Elroy Air. https://elroyair.com/

eVTOL News. (2023). eVTOL Aircraft Directory. https://evtol.news/aircraft

Federal Aviation Administration. (2006, November 15). Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Certification Status [Press release]. https://www.faa.gov/uas/resources/policy_library/media/uas_policyupdate.pdf

Federal Aviation Administration. (2020, March 2). Unmanned Aircraft System Traffic Management Concept of Operations V2.0. https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/2022-08/UTM_ConOps_v2.pdf

FAA. (2022a, June 1). Urban Air Mobility and Advanced Air Mobility. https://www.faa.gov/uas/advanced_operations/urban_air_mobility

FAA. (2022b, June 21). Package Delivery by Drone (Part 135). https://www.faa.gov/uas/advanced_operations/package_delivery_drone

FAA. (2022c). Advanced Air Mobility | Air Taxis. https://www.faa.gov/air-taxis

FAA. (2022d, December 7). Update to Air Carrier Definitions. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/12/07/2022-25711/update-to-air-carrier-definitions

Federal Aviation Administration. (2023a). Drones. https://www.faa.gov/uas

Federal Aviation Administration. (2023b). Our Mission. https://www.faa.gov/about

FDOT. (2022a). Advanced Air Mobility. https://www.fdot.gov/aviation/advanced-air-mobility

FDOT. (2022b, June). Advanced Air Mobility Roadmap. https://fdotwww.blob.core.windows.net/sitefinity/docs/default-source/aviation/fdot-aam-roadmap-report---june-28-2022-final.pdf

FHWA. (2022, August 19). STIC Incentive Program Guidance. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovation/stic/guidance.cfm

Hackenberg, D. (2020). AAM Ecosystem WG Kickoff Mtg [Slides]. NASA. https://nari.arc.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/AAM%20Ecosystem%20WG%20Part%20II_03262020_Welcome%20Slides_0.pdf

Hubbard, S., & Hubbard, B. (2020). A Method for Selecting Strategic Deployment Opportunities for Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) for Transportation Agencies. Drones, 4(3), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones4030029

H.R. 3482 (117th): National Center for the Advancement of Aviation Act of 2022. (2023, January 3). GovTrack. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/117/hr3482

Jacobs, R., & Hawley, J. (2009). Emergence of Workforce Development: Definition, Conceptual

Boundaries, and Implications. http://www.economicmodeling.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/11/jacobs_hawley-emergenceofworkforcedevelopment.pdf

Judson, F., K. Zehnder, J. Bychek, R. Del Rosario, G. Albjerg, B. Kigel, S. Kish, R. Evans, F. Gorrin-Rivas, J. Block, S. Lowry, S. Summer, and A. Guan. (2022, August). Ohio AAM Framework. https://uas.ohio.gov/about-uas/all-news/ohio+publishes+nations+first+advanced+air+mobility+framework

Kesteloo, H. (2023, January 12). Drone Delivery Service Started at two Walmart Locations in Utah. https://dronexl.co/2023/01/12/drone-delivery-service-walmart-utah/

Los Angeles Department of Transportation. (2021, September 13). Urban Air Mobility Policy Framework Considerations. https://ladot.lacity.org/sites/default/files/documents/ladot-uam-policy-framework-considerations.pdf

McNabb, M. (2022, October 5). Drone Delivery in Utah: Zipline and Intermountain Healthcare Launch Program. https://dronelife.com/2022/10/05/drone-delivery-in-utah-zipline-and-intermountain-healthcare-launch-program/

Mehrtens, C. (2020, May 27). Novant Health launches drone operation for COVID-19 response. Healthy Headlines. https://www.novanthealth.org/healthy-headlines/launching-the-first-drone-operation-for-hospitals-pandemic-response

NASA. (2020). NASA AAM. NASA Aeronautics Research Institute. https://nari.arc.nasa.gov/aam-portal/

NASA. (2023). NASA Advanced Air Mobility Ecosystem Working Groups Portal. https://nari.arc.nasa.gov/aam-portal/

Perry, B.J., Y. Guo, R. Atadero, and J.W. van de Lindt. (2020). Streamlined bridge inspection system utilizing unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and machine learning. Measurement, 164, 108048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108048

State Unmanned Aircraft System Legislation. National Conference of State Legislatures. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.ncsl.org/research/transportation/state-unmanned-aircraft-system-2021-legislation.aspx

AASHTO. (2022, May 27). State DOTs Providing Support For AAIM Act. https://aashtojournal.org/2022/05/27/state-dots-support-aviation-infrastructure-modernization-act/

The White House. (2021, August 2). Updated Fact Sheet: Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Retrieved from

Unmanned Aircraft Systems Beyond Visual Line of Sight Aviation Rulemaking Committee Final Report. (2022, March 10). https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/rulemaking/committees/documents/media/UAS_BVLOS_ARC_FINAL_REPORT_03102022.pdf

UPS Flight Forward, CVS to launch residential drone delivery service in Florida retirement community to assist in Coronavirus response. (2020, April 27). UPS Flight Forward. https://about.ups.com/be/en/newsroom/press-releases/innovation-driven/ups-flight-forward-cvs-to-launch-residential-drone-delivery-service-in-florida-retirement-community-to-assist-in-coronavirus-response.html

U.S. Department of Transportation. (n.d.). Strengthening Mobility and Revolutionizing Transportation (SMART) Grants Program. https://www.transportation.gov/grants/SMART

U.S. HR5315. (2023, January 3). Bill Track 50. https://www.billtrack50.com/billdetail/1388593

Vyas, K. (2020, June 29). A Brief History of Drones: The Remote Controlled Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Interesting Engineering. https://interestingengineering.com/a-brief-history-of-drones-the-remote-controlled-unmanned-aerial-vehicles-uavs

Wheeler, P., Mallela, J., LeBris, G., Nguyen, L., Sanchez, D., Schmidt, J., Shaw, K., Tremain, T., Atallah, S., Peterson, S., Herman, E., Dyment, P., and Dyment, M. (2022, December). Utah Advanced Air Mobility Infrastructure and Regulatory Study. https://www.udot.utah.gov/connect/employee-resources/uas/

Whiting, T. (2023, February 2). NASA is Creating an Advanced Air Mobility Playbook. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-is-creating-an-advanced-air-mobility-playbook

WSP, Kimley Horn, & PRR. (2020, November). Washington Electric Aircraft Feasibility Study. https://wsdot.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/WSDOT-Electric-Aircraft-Feasibility-Study.pdf

Zipline - Instant Logistics. (2022, October 4). Zipline and Intermountain Healthcare Begin Drone Deliveries in the Salt Lake Valley. Fly Zipline. https://www.flyzipline.com/press/zipline-and-intermountain-healthcare-begin-drone-deliveries-in-the-salt-lake-valley

Zipline - Instant Logistics. (2023, February 20). Commercial Deliveries. Fly Zipline. https://www.flyzipline.com/

NCHRP 23-20 GUIDEBOOK FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF UAS OPERATIONAL CAPABILITIES

Annotated Bibliography

Prepared for

National Cooperative Highway Research Program

Transportation Research Board

of

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

WSP USA

1250 23rd Street NW, Suite 300

Washington, DC 20037

February 2023

In addition to the Task 1 Technical Memorandum summarizing the literature review, the following annotated bibliography is also provided to demonstrate the thorough review of published research and industry activities.

Annotated Bibliography

| Source # | Citation |

|---|---|

| [1] |

AAAE Airport Consortium on Customer Trust. (2022, December). Advanced Air Mobility. https://www.aaae.org/aaae/ACT/ACT_Resource_Library_Pages/Research/ACT_2.0/AAM.aspx.

|

| [2] |

Albeaino, G., & Gheisari, M. (2021). Trends, benefits, and barriers of unmanned aerial systems in the construction industry: a survey study in the United States. Journal of Information Technology in Construction, 26, 84–111. https://doi.org/10.36680/j.itcon.2021.006

|

| [3] |

Alkobi, J. (2019, January 15). The Evolution of Drones: From Military to Hobby & Commercial. Percepto. https://percepto.co/the-evolution-of-drones-from-military-to-hobby-commercial/

|

| [4] | Balakrishnan, K., Polastre, J. Mooberry, R. Golding, and P. Sachs, “Blueprint for the Sky: The Roadmap for the Safe Integration of Autonomous Aircraft.” Airbus LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, 06-Sep-2018. https://storage.googleapis.com/blueprint/Airbus_UTM_Blueprint.pdf |

|

|

| [5] |

Banks, E., Cook, S., Fredrick, G., Gill, S., Gray, J., Larue, T., Milton, J., Tootle, A., Wheeler, P., Snyder, P., & Waller, Z. (2018, July). Successful Approaches for the Use of Unmanned Aerial System by Surface Transportation Agencies – Domestic Scan 17-01. https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/docs/NCHRP20-68A_17-01.pdf

|

| [6] |

Chappelle, C., Li, C., Vascik, P. D., & Hansman, R. J. (2018). Opportunities to Enhance Air Emergency Medical Service Scale through New Vehicles and Operations. 2018 Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2018-2883

|

|

|

| [7] |

Chen, Y. C., & Huang, C. (2021). Smart Data-Driven Policy on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS): Analysis of Drone Users in U.S. Cities. Smart Cities, 4(1), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4010005

|

| [8] |

Coffey, B. (2019, April 26). Special Delivery: For The First Time, Drone Flies Kidney To Patient For Successful Transplant. General Electric News. https://www.ge.com/news/reports/special-delivery-first-time-drone-flies-donor-kidney-patient-successful-transplant#:~:text=A%20medical%20and%20aviation%20breakthrough,human%20kidney%20from%20Baltimore's%20St

|

| [9] |

Connolly, L., O’Gorman, D., & Tobin, E. (2021). Design and Development of a low-cost Inspection UAS prototype for Visual Inspection of Aircraft. Transportation Research Procedia, 59, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2021.11.100

|

| [10] |

Cornell, A., B. Kloss, D.J. Presser, R. Riedel. (2023, January 3). Drones take to the sky, potentially disrupting last-mile delivery. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/aerospace-and-defense/our-insights/future-air-mobility-blog/drones-take-to-the-sky-potentially-disrupting-last-mile-delivery

|

| [11] | Creedy, K. (2021, February 16). Industry, Academia Must Break Down Silos to Develop Future Workforce. |

https://futureaviationaerospaceworkforce.com/2021/02/16/industry-academia-must-break-down-silos-to-develop-future-workforce/

|

|

| [12] |

Desai, K., Al Haddad, C., & Antoniou, C. (2021). Roadmap to Early Implementation of Passenger Air Mobility: Findings from a Delphi Study. Sustainability, 13(19), 10612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910612

|

| [13] |

Diaz, N. D., Highfield, W. E., Brody, S. D., & Fortenberry, B. R. (2022). Deriving First Floor Elevations within Residential Communities Located in Galveston Using UAS-Based Data. Drones, 6(4), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones6040081

|

| [14] |

Dulia, E. F., Sabuj, M. S., & Shihab, S. A. M. (2021). Benefits of Advanced Air Mobility for Society and Environment: A Case Study of Ohio. Applied Sciences, 12(1), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12010207

|

| [15] |

Dronova, I., Kislik, C., Dinh, Z., & Kelly, M. (2021). A Review of Unoccupied Aerial Vehicle Use in Wetland Applications: Emerging Opportunities in Approach, Technology, and Data. Drones, 5(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones5020045

|

|

|

| [16] |

Eker, U., Fountas, G., Ahmed, S. S., & Anastasopoulos, P. C. (2022). Survey data on public perceptions towards flying cars and flying taxi services. Data in Brief, 41, 107981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2022.107981

|

| [17] |

Garron, J., & Altendorf, J. (2020). Integrating Unmanned Aircraft Systems into Alaskan Oil Spill Response –Applied Case studies and Operational Protocols. http://meridian.allenpress.com/iosc/article-pdf/2021/1/688190/2980429/i2169-3358-2021-1-688190.pdf

|

| [18] |

Goyal, R., & Cohen, A. (2022). Advanced Air Mobility: Opportunities and Challenges Deploying eVTOLs for Air Ambulance Service. Applied Sciences, 12(3), 1183. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031183

|

| [19] |

Goyal, R., Reiche, C., Fernando, C., & Cohen, A. (2021). Advanced Air Mobility: Demand Analysis and Market Potential of the Airport Shuttle and Air Taxi Markets. Sustainability, 13(13), 7421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137421

|

| [20] |

Guirado, R., Padró, J. C., Zoroa, A., Olivert, J., Bukva, A., & Cavestany, P. (2021). StratoTrans: Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) 4G Communication Framework Applied on the Monitoring of Road Traffic and Linear Infrastructure. Drones, 5(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones5010010

|

| [21] |

Hann, R., Enache, A., Nielsen, M. C., Stovner, B. N., van Beeck, J., Johansen, T. A., & Borup, K. T. (2021). Experimental Heat Loads for Electrothermal Anti-Icing and De-Icing on UAVs. Aerospace, 8(3), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace8030083

|

| [22] |

Harper, C., Morrissey, S., & Pardo, R. (2022, December). Integrating Advanced Air Mobility: A Primer for Cities. Urban Movement Labs. https://urbanmovementlabs.org/publications/#reports

|

|

|

| [23] |

Hubbard, S., & Hubbard, B. (2020). A Method for Selecting Strategic Deployment Opportunities for Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) for Transportation Agencies. Drones, 4(3), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones4030029

|

| [24] |

Judson, F., K. Zehnder, J. Bychek, R. Del Rosario, G. Albjerg, B. Kigel, S. Kish, R. Evans, F. Gorrin-Rivas, J.Block, S. Lowry, S. Summer, and A. Guan. (2022, August). Ohio AAM Framework. https://uas.ohio.gov/about-uas/all-news/ohio+publishes+nations+first+advanced+air+mobility+framework

|

| [25] |

Kampas, G., Vasileiou, A., Antonakakis, M., Zervakis, M., Spanakis, E., Sakkalis, V., Leškovský, P., Sanchez-Carballido, S., Gliga, R., Vinković, D., & Pečnik, B. (2022). Design of Sensors’ Technical Specifications for Airborne Surveillance at Borders. Journal of Defence &Amp; Security Technologies, 5(1), 58–83. https://doi.org/10.46713/jdst.005.04

|

| [26] |

Koumoutsidi, A., Pagoni, I., & Polydoropoulou, A. (2022). A New Mobility Era: Stakeholders’ Insights regarding Urban Air Mobility. Sustainability, 14(5), 3128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053128

|

| [27] |

Los Angeles Department of Transportation. (2021, September 13). Urban Air Mobility Policy Framework Considerations. https://ladot.lacity.org/sites/default/files/documents/ladot-uam-policy-framework-considerations.pdf

|

| [28] |

Mallela, J., Wheeler, P., Sankaran, B., Choi, C., Gensib, E., Tetreault, R., & Hardy, D. (2021, March 22). Integration of UAS into Operations Conducted by New England Departments of Transportation - Develop Implementation Procedures for UAS applications. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/56187

|

| [29] |

Mandirola, M., Casarotti, C., Peloso, S., Lanese, I., Brunesi, E., & Senaldi, I. (2022). Use of UAS for damage inspection and assessment of bridge infrastructures. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 72, 102824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102824

|

|

|

| [30] |

Martínez, C., Sanchez-Cuevas, P. J., Gerasimou, S., Bera, A., & Olivares-Mendez, M. A. (2021). SORA Methodology for Multi-UAS Airframe Inspections in an Airport. Drones, 5(4), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones5040141

|

| [31] |

Mehrtens, C. (2020, May 27). Novant Health launches drone operation for COVID-19 response. Healthy Headlines. https://www.novanthealth.org/healthy-headlines/launching-the-first-drone-operation-for-hospitals-pandemic-response

|

| [32] |

Muñoz-Esparza, D., Shin, H. H., Sauer, J. A., Steiner, M., Hawbecker, P., Boehnert, J., Pinto, J. O., Kosović, B., & Sharman, R. D. (2021). Efficient Graphics Processing Unit Modeling of Street-Scale Weather Effects in Support of Aerial Operations in the Urban Environment. AGU Advances, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.1029/2021av000432

|

| [33] |

Perry, B.J., Y. Guo, R. Atadero, and J.W. van de Lindt. (2020). Streamlined bridge inspection system utilizing UAVs and machine learning. Measurement, 164, 108048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.108048

|

| [34] |

Quintanilla García, I., Vera Vélez, N., Alcaraz Martínez, P., Vidal Ull, J., & Fernández Gallo, B. (2021). A Quickly Deployed and UAS-Based Logistics Network for Delivery of Critical Medical Goods during Healthcare System Stress Periods: A Real Use Case in Valencia (Spain). Drones, 5(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones5010013

|

| [35] |

Reiche, C., Goyal, R., Cohen, A., Serrao, J., Kimmel, S., Fernando, C., & Shaheen, S. (2018, November 21). Urban Air Mobility Market Study. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0fz0x1s2

|

| [36] |

Schweiger, K.; Preis, L. Urban Air Mobility: Systematic Review of Scientific Publications and Regulations for Vertiport Design and Operations. Drones 2022, 6, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones 6070179

|

|

|

| [37] |

Silva, M., & Silva, J. (2021). Management of urban air logistics with unmanned aerial vehicles: The case of medicine supply in Aveiro, Portugal. Journal of Airline and Airport Management, 11(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3926/jairm.182

|

| [38] |

Sookram, N., Ramsewak, D., & Singh, S. (2021). The Conceptualization of an Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) Ship–Shore Delivery Service for the Maritime Industry of Trinidad. Drones, 5(3), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones5030076

|

| [39] |

Talaie T, Niederhaus S, Villalongas E, et al Innovating organ delivery to improve access to care: surgeon perspectives on the current system and future use of unmanned aircrafts BMJ Innovations 2021;7:157-163.

|

| [40] |

AASHTO. (2022, May 27). State DOTs Providing Support For AAIM Act. https://aashtojournal.org/2022/05/27/state-dots-support-aviation-infrastructure-modernization-act/

|

| [41] |

Tojal, M., Hesselink, H., Fransoy, A., Ventas, E., Gordo, V., & Xu, Y. (2021). Analysis of the definition of Urban Air Mobility – how its attributes impact on the development of the concept. Transportation Research Procedia, 59, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2021.11.091

|

| [42] |

Tuśnio, N., & Wróblewski, W. (2021). The Efficiency of Drones Usage for Safety and Rescue Operations in an Open Area: A Case from Poland. Sustainability, 14(1), 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010327

|

| [43] |

United States Government Accountability Office. (2022, November). Transforming Aviation - Congress Should Clarify Certain Tax Exemptions for Advanced Air Mobility. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105188

|

|

|

| [44] |

Unmanned Aircraft Systems Beyond Visual Line of Sight Aviation Rulemaking Committee Final Report. (2022, March 10). https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/rulemaking/committees/documents/media/UAS_BVLOS_ARC_FINAL_REPORT_03102022.pdf

|

| [45] |

UPS Flight Forward, CVS to launch residential drone delivery service in Florida retirement community to assist in Coronavirus response. (2020, April 27). UPS Flight Forward. https://about.ups.com/be/en/newsroom/press-releases/innovation-driven/ups-flight-forward-cvs-to-launch-residential-drone-delivery-service-in-florida-retirement-community-to-assist-in-coronavirus-response.html

|

| [46] |

Vempati, L., Woods, S., & Winter, S. R. (2022). Pilots’ willingness to operate in Urban Air Mobility integrated airspace: a moderated mediation analysis. Drone Systems and Applications, 10(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1139/juvs-2021-0009

|

|

|

| [47] |

Wheeler, P., Mallela, J., LeBris, G., Nguyen, L., Sanchez, D., Schmidt, J., Shaw, K., Tremain, T., Atallah, S., Peterson, S., Herman, E., Dyment, P., and Dyment, M. (2022, December). Utah Advanced Air Mobility Infrastructure and Regulatory Study. https://www.udot.utah.gov/connect/employee-resources/uas/

|

| [48] |

WSP, Kimley Horn, & PRR. (2020, November). Washington Electric Aircraft Feasibility Study. https://wsdot.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/WSDOT-Electric-Aircraft-Feasibility-Study.pdf

|

| [49] |

Zhang, Y., & Wu, Z. (2021). Modeling and Evaluating Multimodal Urban Air Mobility (U.S. Department of Transportation 69A3551747119). https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/110717

|

| [50] |

Zipline - Instant Logistics. (2022, October 4). Zipline and Intermountain Healthcare Begin Drone Deliveries in the Salt Lake Valley. Fly Zipline. https://www.flyzipline.com/press/zipline-and-intermountain-healthcare-begin-drone-deliveries-in-the-salt-lake-valley

|