A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health (2025)

Chapter: 7 Overview of Selected Women's Health Conditions

7

Overview of Selected Women’s Health Conditions

A wide range of conditions are specific to females,1 more prevalent among women, or affect women differently than men (see Table 7-1). Moreover, as a result of insufficient research and measurement, it remains unclear the full extent of conditions that uniquely affect women. While it was not possible for the committee to review every women’s health condition in depth, it presents a framework in this chapter for quantifying and categorizing health conditions that affect women’s morbidity, mortality, and quality of life in different ways and selects exemplar conditions to illustrate pressing needs for further research investment in women’s health scientific investigation. Together, the examples across the life course highlighted in this chapter represent those that are present in women and men but progress differently in and cause greater disability in women (e.g., mood disorders) or cause more premature mortality in women compared to men (e.g., cardiometabolic diseases, autoimmune disease, and Alzheimer’s disease [AD]); are female specific and leading causes of death (e.g., gynecological cancers); and are female specific and a leading cause of reduced quality of life and disability (e.g., endometriosis, fibroids, and perinatal and menopause-related depression). Because pregnancy influences the trajectory of cardiometabolic and cognitive disease later in life, the chapter also summarizes its effects across the life course.

___________________

1 The terms “female” and “woman” are used differently according to context and perspective, which may cause confusion (see Chapter 1). In this chapter, the committee uses “female” when discussing specific sex traits related to a specific condition and “woman” when discussing the population more generally (the latter includes all people who identify as a woman or girl, solely or in addition to other gender identities and regardless of biological sex traits).

Two recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) reports comprehensively reviewed and identified research gaps for two pressing women’s health topics: autoimmune disease and chronic conditions (see Box 7-1 for a summary of the conditions). The findings of those reports corroborate the research needs this committee identified; it relied upon and attempted not to duplicate the effort of these reports. Boxes 7-2 and 7-3 provide a summary of key recommendations to address research gaps from those reports.

BOX 7-1

Women’s Health Conditions Reviewed in Enhancing National Institutes of Health Research on Autoimmune Disease and Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women

Conditions reviewed in Enhancing NIH Research on Autoimmune Disease (2022)

- Sjögren’s disease

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Antiphospholipid syndrome

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Psoriasis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Celiac disease

- Primary biliary cholangitis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Type 1 diabetes

- Autoimmune thyroid diseases

Conditions reviewed in Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women (2024)

- Endometriosis/dysmenorrhea/chronic pelvic pain

- Uterine fibroids

- Infertility

- Vulvodynia

- Pelvic floor disorders (including urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse)

- Menopausal symptoms (including exogenous hormone use)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Multiple sclerosis (also affects the neurocognitive system)

- Osteoporosis

- Sarcopenia

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Migraine/headache

- Chronic pain

- Fibromyalgia

- Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome

- Cardiovascular disease

- Stroke

- Metabolic conditions (Type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome)

- Depression

- Substance use disorder

- Human immunodeficiency virus

SOURCES: NASEM, 2022, 2024b.

NOTE: These are a combination of conditions that are female specific, are more common in women, or impact women differently.

BOX 7-2

Enhancing National Institutes of Health Research on Autoimmune Disease: Summary of Recommended Research Priorities

This report identified several crosscutting research needs for autoimmune disease and recommended research to address gaps in knowledge, including to

- Dissect heterogeneity across and within autoimmune diseases to decipher common and disease-specific pathogenic mechanisms.

- Study rare autoimmune diseases and develop supporting animal models.

- Define autoantibodies and other biomarkers that can diagnose and predict the initiation and progression of autoimmune diseases.

- Determine the biologic functions of genetic variants and gene–environment interactions within and across autoimmune diseases using novel, cutting-edge technologies.

- Examine the role of environmental exposures and social determinants of health in autoimmune diseases across the life-span.

- Determine the impact of coexisting morbidities, including co-occurring autoimmune diseases and complications of autoimmune diseases, across the life-span, and develop and evaluate interventions to improve patient outcomes.

- Foster research to advance health equity for all autoimmune disease patients.

SOURCE: NASEM, 2022.

BOX 7-3

Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women: Summarized Research Agenda

The report identified key research gaps that the National Institutes of Health and other relevant agencies that fund research should support to advance the understanding of chronic conditions in women. The following areas of research were recommended to help fill those research gaps.

Recommendation 1: Impact—improve estimates and support national surveillance and population-based studies; expand data collection activities to include female-specific and gynecologic and female-predominant conditions not currently included.

Recommendation 2: Biology and Pathophysiology—understand how gonadal hormones and sex chromosome genes interact to cause sex differences, role of inflammation and immune system, and genetic heterogeneity of conditions (e.g., endometriosis); improve animal and preclinical models.

Recommendation 3: Female-Specific Risk Factors—the specific role of reproductive milestones across the life course (e.g., menarche, pregnancy, perimenopause, menopause, and postmenopause) and address symptoms.

Recommendations 4–6: Disparities and Life Experiences—interaction of multiple social identities with structural and social determinants of health; role of traumatic experiences; role of lifestyle behaviors.

Recommendation 7: Diagnosis and Treatment—improve early and accurate detection and diagnosis of chronic conditions; develop sex- and gender-specific tools; establish better diagnostic tools of conditions that share similar symptoms (e.g., chronic pain, fibromyalgia).

Recommendation 8: Multiple Chronic Conditions—understand biological mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment and care for women with multiple chronic conditions; develop research approaches to appropriately study and include women with multiple chronic conditions.

Recommendation 9 & 10: Inequities and Women-Centered Research—develop methods for assessing structural determinants of health such as sexism and ageism; recruit women from different backgrounds and use novel techniques for engaging women; account for sex and gender in studies.

SOURCE: NASEM, 2024b.

A FRAMEWORK FOR QUANTIFYING DISEASE BURDEN TO ILLUSTRATE WHR GAPS

This section illustrates the annual burden of disease experienced by women in the United States in terms of years of life lost (YLLs), years lived with disability (YLDs), and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Further, it demonstrates through simplified examples how such analyses can help in setting priorities for women’s health research (WHR) by identifying imbalances in health research investments. The committee used this analytic approach to frame the discussion of key exemplar conditions affecting women’s health later in this chapter.

The Value of Research Investment and Metrics for Quantifying Disease Burden

The burden of different health conditions and the opportunities for research to alleviate it (i.e., the expected health return on research investment) are important factors in decisions about allocating a limited pool of funding. Both are difficult to quantify and involve substantial uncertainty; in particular, the latter requires assumptions about potential advancements and breakthroughs. This section describes available metrics to quantify disease burden and explores their application to funding allocation decisions. The committee assumes that investments in women’s health would have at least as much potential for health returns as investments in other areas, which is conservative given the historical underinvestment in WHR described in Chapters 2 and 4. The analysis therefore focuses on quantifying the burden of disease that could be addressed by WHR. In practice, such analyses would ideally consider both of these metrics and other factors, including expected research returns, explicit investment in historically neglected areas, and the minimum threshold needed to ensure progress across a range of areas.

A key challenge for quantifying the burden of disease and comparing the health effects of different conditions is determining comparable outcomes across disease areas. For example, health effects can be measured in terms of people affected using metrics such as incidence (the number of new cases per unit of time, often annually) and prevalence (the number of individuals affected in some time period). Other metrics, such as annual deaths, also reflect disease severity. In comparing diseases, qualitative differences in burden across health problems present critical challenges, such as how to compare the societal health effect of endometriosis, a condition affecting roughly 11 percent of reproductive-age women—approximately 1 in 26 U.S. women—that can cause severe abdominal pain; persistent or recurring genital pain before, during, or after intercourse (dyspareunia); and

infertility, to that of gynecological cancers, which affect approximately 1 in 168 U.S. women but more frequently cause mortality (Buck Louis et al., 2011; Ellis et al., 2022; IHME, n.d.-a; Stewart et al., 2013). A similar challenge is how to compare the effect of a chronic illness, such as asthma, to that of a brief but severe episode of acute illness, such as influenza or COVID-19.

The committee drew on the validated approach of aggregated health metrics, which include both DALYs and related measures, such as quality-adjusted life years. These standardized methods are widely used both nationally and internationally and aggregate nonfatal and fatal health effects into comparable measures (Augustovski et al., 2018; NCCID, 2015; Sassi, 2006). Furthermore, they integrate the type and duration of health effects to quantify burden in a way that can be easily compared across disease areas. Although these measures have limitations, discussed later, such analyses can nevertheless provide insights into comparisons among all women’s health conditions.

Understanding DALYs

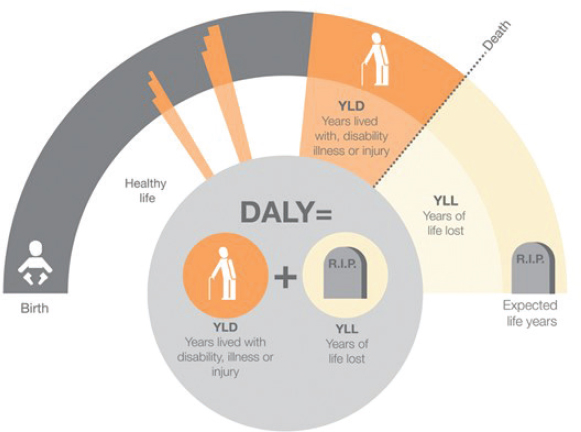

In this chapter, burden of disease is quantified in terms of DALYs, which measure the loss of health resulting from disease or injury, where a year lived in perfect health is denoted as 0 and a year of life lost is denoted as 1. In general, health interventions seek to avert or reduce DALYs. Because health conditions may cause impaired quality of life or loss of life, DALYs are the sum of YLLs and YLDs (Salomon et al., 2012). Figure 7-1 displays this breakdown, with YLDs, marked in orange, accruing both as a result of temporary and chronic conditions and YLLs, marked in beige, showing years of life lost compared to a full healthy life expectancy.

To calculate YLLs, researchers compare an estimate of the average age at death for a particular condition to an estimate of an average full healthy life expectancy. To calculate YLDs, researchers use weights that convert the health burden of different conditions into a number of effective years lost. Usually, standardized DALY weights come from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study that presented an international sample of individuals with two descriptions of health states and asked which scenario described a healthier individual (Salomon et al., 2012, 2015). Using another series of questions, these ratings were anchored onto the 0–1 scale described. Given the extremely high correlations across nations,2 researchers designed only one scale of DALY weights, which are regularly updated, calculated in a standard way across conditions, and applied broadly. The weights are publicly available (IHME, n.d.-c; Salomon et al., 2012).

___________________

2 Nations included Indonesia, Peru, Bangladesh, Tanzania, and the United States in 2009–2010, and Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, and Sweden were added in 2013 GBD analysis (Salomon et al., 2015).

SOURCE: U.K. Health Security Agency, 2015; licensed by Open Government Licence v3.0 (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/).

Analyses

This section provides descriptive statistics for the burden of female diseases in estimates from the GBD study, characterizing the burden’s distribution across conditions and comparing it to the male burden. Second, this section uses stylized benchmarking analyses to explore how decision makers may use data that measure the burden of illness in a standardized to inform funding allocation and priority setting decisions in WHR.

Descriptive Statistics

Data

The GBD study regularly provides publicly available and comprehensive estimates of the frequency and burden of all health conditions in the United States by sex. The concept of DALYs is organized into a hierarchical structure with multiple levels to provide a comprehensive view of health loss (see Box 7-4). The committee extracted annual prevalence, incidence, DALYs, YLLs, and YLDs across all available disease areas by sex from GBD 2021 U.S. estimates, the most recent year available, for Level 3 causes, the most granular comprehensive level in the GBD database (IHME, n.d.a). For outcomes of particular women’s health interest, annual incidence and prevalence, the committee benchmarked estimates against external, independent estimates from the peer-reviewed literature, generally finding equivalence, with limitations as noted. The committee excluded COVID-19

BOX 7-4

Disability-Adjusted Life Year Categories

The DALY hierarchical framework has three or four levels, depending on the level of analysis:

Level 1 is the highest level of aggregation and includes noncommunicable diseases; injuries; and a group of infectious diseases, maternal and neonatal disorders, and nutritional deficiencies. This level provides a broad overview of the major types of health issues affecting populations.

Level 2 breaks down the Level 1 categories into more specific risk categories: 22 disease and injury aggregate categories, such as respiratory infections and tuberculosis, cardiovascular diseases, and transport injuries.

Level 3 further refines the risk categories into more specific causes, such as tuberculosis, stroke, and road injuries. In some cases, Level 3 causes are the most detailed classification, while for others, a more detailed category is specified at Level 4.

Level 4 is not consistently defined across conditions, and its use varies depending on the study and level of detail required.

SOURCES: GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators, 2024; IHME, n.d.-b.

from the analysis given its anomalous burden in 2021; burden estimates were otherwise comparable to 2019.

Methods

For reporting and display purposes, the committee aggregated 175 Level 3 conditions into 17 categories, adjusting standardized Level 2 categories to highlight outcomes of interest, such as separating out female-specific cancers. Outcomes are presented by sex, condition, and type in terms of DALYs, YLLs, and YLDs.

Burden of Female Disease

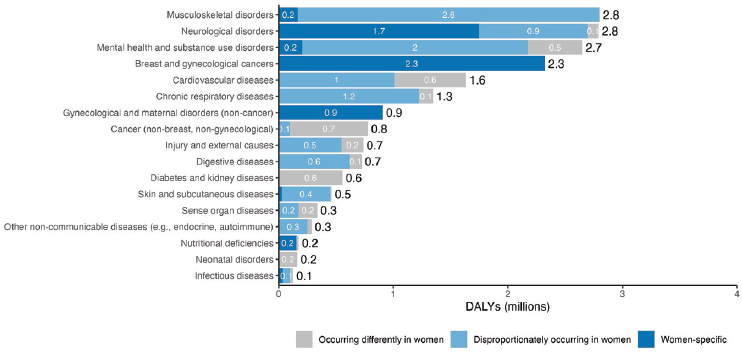

Figure 7-2 summarizes estimated 2021 DALYs by disease category, sex (top panel), and type (bottom panel). Overall, men have a higher number of DALYs than women (who were 49 percent), but women experienced a disproportionate share of disability (55 percent of YLDs). For both, mental health and substance use disorders were the most common DALY categories,

NOTES: The top panel displays DALYs by sex. The bottom panel displays only female-specific DALYs, decomposed into years of life lost (YLLs) and years lived with disability (YLDs).

followed by cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer, with men experiencing a majority of DALYs in these conditions. By contrast, among conditions experienced by both men and women, women had a majority of DALYs related to musculoskeletal, chronic respiratory, and neurological conditions.

The bottom panel of Figure 7-2 further breaks down contributions of disability and mortality to the female DALY burden. The dark blue portion of each bar shows the YLLs attributable to each condition. The light blue portion shows DALYs resulting from time spent with disability, such as loss of quality of life through physical or mental health limitations or discomfort. CVD and cancers are the main drivers of YLLs among

women. In contrast, for mental health, substance use, and musculoskeletal disorders, DALYs from mental health conditions are attributable primarily to disability. The former may be, in part, an artifact of GBD coding—several mental health conditions, such as depression leading to suicide and schizophrenia, are also associated with premature mortality (Schoenbaum et al., 2017; Vigo et al., 2022). Some women-specific health conditions, such as female-specific cancers, gynecological problems, and female sexually transmitted infections, constitute a smaller total DALY burden compared to other categories, though female-specific cancers are the fourth-leading cause of premature mortality among women through YLLs. The next section discusses the challenge of connecting the burden of female disease and disability to WHR.

Benchmarking

While these descriptive results characterize the overall burden of disease in women, further analysis would be required to inform funding allocation with disease burden. The following presents two stylized examples of how burden data could inform resource allocation.

Cancer funding is considered as a simplified example of within–National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institute and Center (IC) prioritization; in this case, comparing spending on female-specific and non-female-specific cancers. Approaches to delineating the total burden of disease that research on women-specific diseases and those that affect women disproportionately or differently might address are then explored.

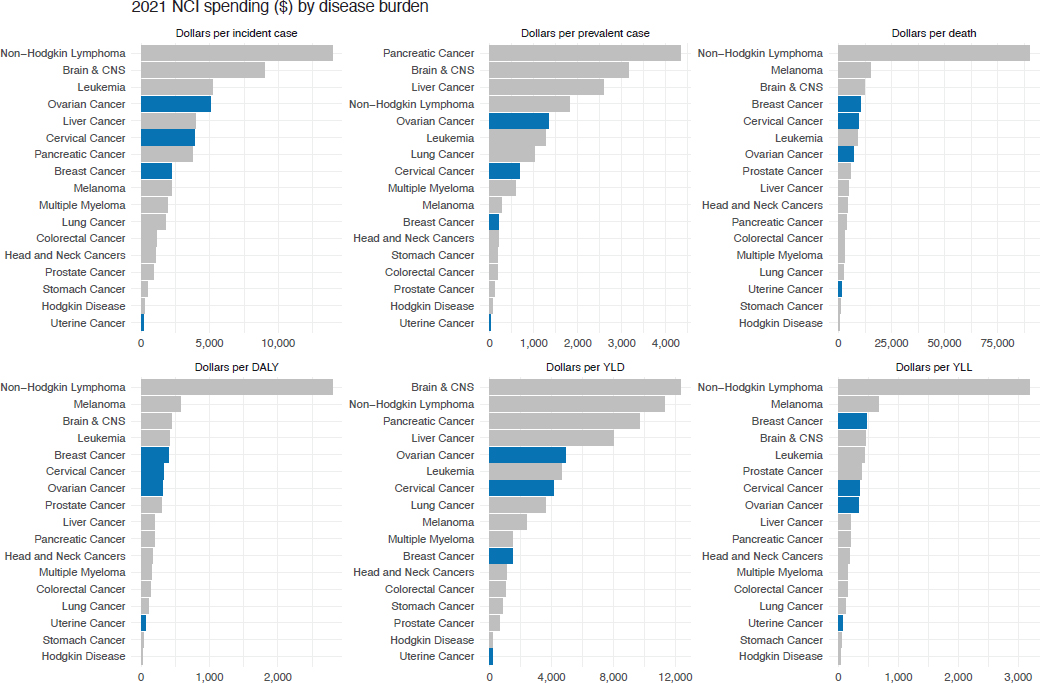

- Cancer spending This is a discrete, well-defined case study that allows comparing investments in female-specific or predominant disease subtypes, including breast, uterine, cervical, and uterine/endometrial, to cancers affecting both men and women. National Cancer Institute (NCI) data were extracted on estimated 2021 spending across 17 cancer types (NCI, 2024e). For each type, spending was divided by total 2019 burden measures (e.g., DALYs, YLLs, YLDs), summed over both sexes, to understand how research investment compared each type’s health burden. Although this exercise is simplified by considering only 1 year of data and crudely comparing female-specific to non-female-specific cancers, this approach can highlight areas of underinvestment relative to disease effects.

- WHR portfolio Next, a more challenging question is considered—the fraction of the total U.S. disease burden falling under the purview of WHR, defined as encompassing conditions that are female specific, are disproportionately female, or affect women

- differently. Most people would not consider research on any disease affecting women to be “WHR,” since that would encompass nearly all modern clinical research, be so overly broad as to obscure the gaps and barriers discussed in this report, and overlook the value of research that studies two sexes. Nevertheless, as this report elucidates, adequately addressing women’s health issues requires understanding sex differences in disease pathways and presentation. Such research is critical for women’s health and well-being, including in domains such as CVD, for which women experience 43 percent of the overall DALY burden.

To provide a simplified schematic that addresses this balance, the committee divided the 175 level 3 GBD categories by those disproportionately occurring in women (more than 67 percent of DALYs); those more common in women (51–67 percent of DALYs); and other conditions (50 percent or fewer DALYs but often occurring differently in women). Next, the committee estimated the proportion of WHR-related DALYs, attributing 100 percent of female DALYs in the first category to women’s health, 50 percent in the second, and 33 percent in the third. This was intended to include contributions of both domains that traditionally fall entirely under the purview of WHR, such as gynecological conditions, and conservatively estimate the need for research powered to detect or focused specifically on sex differences. DALYs were reported by condition, category, and percentage of overall disease burden falling in this category.

Cancer spending

Figure 7-3 summarizes spending per unit of disease burden across cancer types, summarizing the ratio of fiscal year (FY) 2021 NCI reported spending to 2019 cancer incidence, prevalence, deaths, DALYs, YLLs, and YLDs in males and females. In each case, some female-specific cancers (blue bars) receive less NIH funding than many other cancers. In particular, uterine cancer ($57 per DALY) receives markedly lower funding per DALY compared to conditions such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma ($2,794), brain cancer ($444), and pancreatic cancer ($190).

WHR portfolio

Figure 7-4 presents estimates related to a potential WHR portfolio. It highlights important contributions of both female-dominant and specific conditions, such as breast and gynecological cancers and gynecological and maternal disorders, and other conditions (e.g., musculoskeletal, mental health, and substance use disorders) relevant to women’s health.

Overall, this classification encompasses 34 percent of all female DALYs and 16 percent of U.S. DALYs across both men and women. This framework

NOTE: Blue bars indicate female-specific cancers.

NOTE: These include all female DALYs for female-specific conditions (more than 67 percent of DALY disease burden in women) and a fraction of female DALYs for conditions experienced disproportionately in women (50 percent) or differently in women (33 percent).

is simplified and likely conservative: DALY estimates may be underestimates of the true prevalence of women’s disease burden due to underdiagnosis (see Box 7-5), and as noted, this analysis does not account for lack of investment in basic science related to women’s health (see Chapter 5), which would likely increase relative returns on investment. This rough estimate nevertheless provides a striking benchmark in comparison to the committee’s funding analysis in Chapter 4—for NIH funding on WHR (which averaged 8.8 percent from FY 2013 to FY 2023) to reach this 16.5 percent burden estimate, it would need to increase by nearly twofold (87.5 percent). These burden estimates guide the discussion of conditions in this chapter.

Rare Diseases

One concern is that metrics focusing on population prevalence overlook rare diseases; funding research in proportion to DALYs would risk stunting progress toward preventing and treating rare illnesses.3 In practice, there is a strong societal preference for investment in serious disabling conditions, even if they affect only a small number of people. Furthermore, making therapeutic progress for any condition requires a minimum threshold of investment, which may require funding rare conditions disproportionately to burden.

___________________

3 According to the Orphan Drug Act, a disease or condition is considered rare if it affects fewer than 200,000 Americans (Public Law 97–414). [This footnote was changed after release of the report to clarify the source of the definition.]

DALYs per affected individual may also be considered to illustrate the concentration of disease burden. Nevertheless, tradeoffs remain challenging: how is a rare, severe neurological condition, such as Rett syndrome, which affects only one in 10,000 female individuals, weighted against a much more common but less debilitating condition, such as endometriosis or osteoarthritis?

A Framework for Selecting Exemplar Conditions Illustrating WHR Gaps

Several limitations to these analyses—and the use of DALYs or aggregated metrics more broadly—may merit consideration or further study when using disease burden analysis to identify research gaps and support funding decisions (see Box 7-5). Although DALYs are an imperfect metric, they

BOX 7-5

Limitations of Disability-Adjusted Life Years and Future Directions for Health Metrics

DALYs and other aggregated health metrics can only provide insight related to the burden of disease for specific conditions. This approach is less useful for informing less-targeted basic science research or research focused on health-promotion, such as supporting contraceptive use.

There are also several limitations specific to the GBD study calculation of DALY weights.

- Weights were calculated by soliciting paired comparisons about the “health” of individuals experiencing various conditions. Some conditions, such as infertility, may substantially affect quality of life but have a low disability weight due to perceptions that the impact does not fall into the category of “unhealthy.”

- GBD weights are being updated, particularly to account for women’s health conditions. For example, new weights for dyspareunia and chronic conditions will be in a forthcoming update.

- In some cases, GBD burden estimates differ from those in other sources. For example, GBD reports a much lower prevalence of endometriosis than other estimates. This may arise because GBD prevalence estimates are differentially affected by diagnosis. For example, estimates of premenstrual disorder include self-reported survey responses, while endometriosis requires surgical diagnosis.

Additional research to contextualize DALYs to account for differential circumstances in which disability is experienced, such as social support and economic resources, would be valuable.

remain a widely applied measure that allow comparisons across diseases and sequelae. Therefore, despite these limitations, the committee found this to be a useful framework for identifying exemplar conditions to illustrate WHR needs and create a matrix of women’s health conditions (see Table 7-1). Some conditions could fit into two categories, but for this overview, conditions are discussed in the DALY category based on the committee’s analysis.

EXEMPLAR WOMEN’S HEALTH CONDITIONS

In this section, the committee provides a brief overview of some of the research gaps that fall into the categories identified in the matrix in the DALYs section (see Table 7-1).

FEMALE-SPECIFIC CONDITIONS WITH INCREASED DALYS RESULTING FROM DISABLING CONDITIONS

The 2024 National Academies report Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women reviewed several female-specific conditions that increase DALYs as a result of disability and affect a significant proportion of women (NASEM, 2024b). This section highlights and summarizes several of these conditions, including uterine fibroids (leiomyomas), endometriosis, pelvic floor disorders, and female-specific mental health conditions (see NASEM, 2024b for an in-depth overview of these conditions).

Gynecological Conditions

Fibroids

Fibroids are the most common solid tumor of the pelvis and the leading cause of hysterectomy in the United States (Bulun, 2016; Marsh et al., 2024). While benign, they can lead to significant symptoms, including irregular and excessive uterine bleeding, lower abdominal pressure, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), infertility, and adjacent organ compression (Bulun, 2016; Marsh et al., 2024; NASEM, 2024b). Fibroids are more common in African American and Black females (Eltoukhi et al., 2014), who are also more likely to develop uterine fibroids at an earlier age, have larger-sized and greater number of fibroids, and experience more severe symptoms (Marsh et al., 2024). Despite their high prevalence, little is known about their pathophysiology. While researchers have studied estrogen as a mitogen for myoma growth, little research has been done to understand the role of other hormonal and non-hormonal factors in fibroid development and why they are more prevalent in Black females (Bulun, 2016; Cetin et al., 2020; NASEM, 2024c; Reis et al., 2016; Sefah et al., 2022). Given the high prevalence and morbidity, additional research

TABLE 7-1 Matrix of Women’s Health Conditions

| Affect only females | Affect only females | Affect only females | Differentially or disproportionately affect women | Differentially or disproportionately affect women | Differentially or disproportionately affect women |

| DALYs resulting from disabling conditions | DALYs resulting from early mortality | DALYs resulting from disabling conditions AND early mortality | DALYs resulting from disabling conditions | DALYs resulting from early mortality in women, and/or mortality in women versus men | DALYs resulting from disabling conditions AND early mortality in women, and/or early mortality in women versus men |

| Large population effect on females | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTES: This table does not cover all conditions that affect only females or disproportionally or differentially affect women; it is a selection of conditions based on the committee’s DALY analysis. For example, additional important female-specific conditions include vulvar and vaginal cancers and vulvodynia. DALY = disability-adjusted life year; * Breast cancer does affect men, but less than 1 percent of all U.S. breast cancer diagnoses are in men.

is needed across the entire translational spectrum to better understand the pathophysiology so that novel targeted medical and surgical treatments can be developed and disseminated (NASEM, 2024b).

Endometriosis

Despite endometriosis being one of the most common causes of infertility and chronic pelvic pain, its cause, risk factors, and true incidence remain uncertain (NASEM, 2024b; Young, 2024). It has no nonsurgical approach to diagnosis, and surgical treatments requiring hysterectomy and hormonal medical treatments are incompatible with fertility and fecundity (Young, 2024). It is also a risk factor for development of ovarian cancer and other chronic pain conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome (Barnard et al., 2024; Nabi et al., 2022). A population-based study found that those who developed endometriosis were 4.2 times more likely to develop ovarian cancer compared to those without endometriosis (Barnard et al., 2024). Additional research is needed to understand the pathophysiology and develop fertility-sparing approaches to treat this debilitating condition.

Pelvic Floor Disorders

Pelvic floor disorders, which are also common and significantly affect quality of life, lead to pelvic organ prolapse, urinary and fecal incontinence, recurrent urinary tract infections, bladder pain syndrome, and myofascial pelvic pain. Pelvic organ prolapse specifically occurs in up to 50 percent of female patients, but there are significant knowledge gaps in the basic science understanding of normal and abnormal pelvic floor function and the structural aspects of pelvic floor support (Aboseif and Liu, 2022; Swenson, 2024). A better understanding of pelvic floor function and its hormonal, structural, and functional determinants will enable more effective interventions. These are sorely needed given the high surgical treatment failure rate, impairing female quality of life (Swenson, 2024).

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS is the most common endocrine disease in female patients and a leading cause of female impaired fecundity (Akre et al., 2022). It is a complex hormonal, metabolic, and reproductive disorder affecting multiple organ systems and afflicting approximately 4–18 percent of reproductive-age females (Bozdag et al., 2016; Dennett and Simon, 2015). Research has yet to fully elucidate the etiology, although in the majority of patients, it appears to be linked to some combination of polycystic ovarian morphology, hyperandrogenism, and ovulatory dysfunction. Many people are

unaware they have it, as it is often characterized by myriad heterogenous signs and symptoms. The Rotterdam diagnostic criteria are the most accepted, requiring two of the following three features: hyperandrogenism, oligo- or anovulation causing missed or irregular periods, or polycystic ovaries (Christ and Cedars, 2023). The hyperandrogenic state is proposed to contribute to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia and ultimately adiposity, or excessive body fat accumulation. PCOS can lead to significant medical conditions, including CVD, Type 2 diabetes, impaired fecundity, fatty liver disease, endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial cancer, some of which may develop as a function of higher levels of body fat. It has no cure and no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies (Allen et al., 2022; Dennett and Simon, 2015; NASEM, 2024c).

Additional research is needed to better delineate the underlying cause; understand the complex interplay of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors associated with PCOS; identify curative therapies; assess long-term cardiovascular, metabolic, and cognitive decline risks; and identify mitigation strategies to prevent comorbid conditions (Che et al., 2023; Christ and Cedars, 2023). Recent research has also highlighted the need for further investigations on PCOS and its relationship to brain health during midlife (Huddleston et al., 2024). Despite its prevalence among females and substantial research gaps, PCOS also ranks near the bottom among NIH-funded conditions, according to the committee’s funding analysis (see Chapter 4).

Additional gynecological conditions that take a significant toll on the lives of women and lead to disability are discussed in the 2024 report, including vulvodynia (NASEM, 2024b). The committee heard from many brave individuals who shared their experiences with gynecological conditions during the committee’s information-gathering stage; see Box 7-6 for some of their experiences.

Funding Shortfall

A significant challenge to advancing research on these female-specific conditions is that noncancer gynecological conditions lack an NIH funding home among the current ICs. Figure 7-5 illustrates this contrast—even though more females are affected by endometriosis and PCOS than breast cancer, there is a paucity of funding for these conditions relative to breast cancer. Without a dedicated funding stream and NIH study sections that include the proper scientific expertise to review grants submitted on these conditions, there is a missed opportunity to advance scientific discoveries and treatments that will significantly improve quality of life and productivity for a significant proportion of the female population. It is critical to increase funding for these conditions to be on par with female-specific cancers.

BOX 7-6

In Their Own Words: Excerpts from Patients and Patient Advocates on Gynecologic Conditions During Public Comments at Committee Meetings

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

- There isn’t enough funding for research across women’s health, but PCOS is an interesting case where it’s a really prevalent disorder globally impacting 8 to 13 percent of women. Yet PCOS wasn’t even listed in NIH’s Research Condition Diseases Category reporting, the RCDC, until our organization’s advocacy work. And so, this highlights that there are certain aspects of women’s health which haven’t been prioritized even though it impacts so many of us.

- We need to implement policies to ensure equitable funding and focus across diseases affecting women of all backgrounds. PCOS disproportionately impacts women of color and their metabolic health, mental health, et cetera, yet there is very little funding in this area, and very few Black researchers who are getting funded. So, thinking about not only who we are studying but who’s doing the research and care as well.

Pelvic Floor Disorders

- Pelvic floor disorders cause musculoskeletal dysfunction, pain, loss of productivity, decline in self-esteem, relationship difficulties, mental health issues, just to name a few. Frequently, for pelvic floor research, we may see a study done with 30 subjects or a case study done with 1–3 people simply because NIH has not funded or prioritized research in this area. The data are shocking.

- Pelvic floor research is divided throughout NIH, and it has not focused on women’s pelvic health through the life-span. The result is, without research data, the diagnostic criteria is variable. We don’t have well-researched treatment options. Therefore, women cannot get the treatment and the services they need covered by health care.

Fibroids

- The lived experience of women with uterine fibroids is, I believe, a societally dismissed experience in communities worldwide that is steeped in a millennia old stigma that is expected that women will endure immense pain. Today in many countries women are still community outcast during their menstrual cycles.

Endometriosis

- I’m not being alarmist when I say the lives of more than 6 million women nationwide quite literally depends on [more research]. Endometriosis has affected every single aspect of my life. It has ravaged my body beyond repair, destroyed relationships, stripped me of identity.

- At just 27 years old, it forced me to go on medical disability from work for over a year. It forced me to drop out of graduate school, just one class short of earning a master’s degree. And I wish my story of turmoil and loss due to endometriosis were unique, but sadly, it is just one of millions.

- Despite my medical background and knowledge, it still took me over 4 years and 10 specialists ranging from pulmonology to cardiothoracic surgery to gastroenterology to be officially diagnosed with diaphragmatic endometriosis.

Vulvodynia

- Despite how common this condition is, it took years of going from doctor to doctor to get diagnosed. Clinicians told me to drink wine to relax before sex and seemed to incorrectly attribute my pain to something psychological. Meanwhile, I was trying to figure out how to sit and move without hurting. This was one of the most upsetting and isolating periods of my life, trying to find out why I was having this severe and terrifying pain, and why no provider seemed to take it seriously.

- Diagnosis was half the battle; treatment is another. I spent years trying every imaginable treatment and medication. Everything I have tried was off-label since there is no FDA-approved drug for any kind of chronic vulvovaginal pain. There is an effective surgery but it’s only done by a few surgeons in the country and can cost tens of thousands of dollars out of pocket.

- It’s daunting to stare down a lifetime of chronic pain, and it is made so much worse by the fact that most doctors, even OB-GYNs, have not heard of this issue. We need hope that some attention is going to be paid to finding effective treatments for this devastating diagnosis.

SOURCE: Committee’s funding analysis (see Chapter 4).

Mental Health Conditions

Perinatal Depression

Perinatal depression, a major depressive disorder that occurs during pregnancy or in the first 12 months following childbirth, appears in approximately 10–20 percent of pregnancies in the United States and, along with other mental health conditions, is the leading cause of maternal mortality, accounting for 23 percent of maternal deaths (Dagher et al., 2021; Payne and Maguire, 2019; Sayres Van Niel and Payne, 2020; Trost et al., 2022). Specifically, 1 in every 7–10 pregnant people and 1 in every 5–8 postpartum people develop a depressive disorder, which translates to more than a half million cases each year, approximately the same number diagnosed with diabetes (Sayres Van Niel and Payne, 2020). Like diabetes, perinatal depression is a costly and potentially fatal condition, with its annual cost totaling at least $15 billion, or more than $22,600 per mother and infant, yet unlike diabetes, 91–93 percent of those with perinatal depression do not receive effective treatment (Cox et al., 2016), an enormous gap in clinical care.

As discussed in Chapter 5, NIH investment in research to understand the neuroendocrine mechanisms of perinatal depression resulted in

two FDA-approved, highly effective treatments using allopregnanolone, a neuro-receptor modulator. It took over 80 years, however, from compound discovery to translation to treatment, and despite the advances, research funding for allopregnanolone and perinatal stress and depression remained much lower than other chronic conditions, such as breast cancer, afflicting a similarly large segment of the U.S. population (Deligiannidis, 2024; Pinna, 2020; Reddy et al., 2023). This funding trend has persisted (see Chapter 4 for more information), and important barriers to care, including a lack of screening and diagnosis, prevent most women from receiving effective treatment.

Psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for perinatal depression (Cuijpers and Karyotaki, 2021), and 92 percent of pregnant people prefer individual therapy to group treatment or medication (Goodman, 2009). However, only 7 percent of those with perinatal depression receive effective treatment because of systemic barriers to care (Cox et al., 2016), including cost, limited numbers of mental health specialists, geographic distance from specialty clinics, scheduling challenges arising from work-related and childcare demands, and stigma associated with seeking mental health care (Byatt et al., 2012; Dagher et al., 2021; Hellberg et al., 2023).

Moreover, although the new fast-acting, FDA-approved medications reduce depressive symptoms more rapidly and to a greater degree than earlier medications, they are not effective for about one-third of females; can only be used in the postpartum period, even though most cases of perinatal depression begin during pregnancy; have not been tested in lactating women; cannot be used as a prophylactic; and may be difficult to access given the cost and need for specialist prescribers and specialized treatment facilities that can provide inpatient hospitalization in facilities with 1:1 nursing supervision, for example (Meltzer-Brody et al., 2018; Patterson et al., 2024; Reddy et al., 2023). Of all the reproductive-related mood disorders, perinatal depression has received the most funding and has the strongest scientific foundation upon which to build rapid advances in identifying neurobiological mechanisms, objective diagnostics, novel treatments, and prevention, but realizing that potential still requires substantial monetary investment (Deligiannidis, 2024).

Menopause-Related Depression

The transition to menopause, or perimenopause, is characterized by irregular menses, vasomotor symptoms, sleep and sexual disturbances, weight gain, lassitude, cognitive dysfunction, vaginal dryness, urinary symptoms, and mood symptoms (Woods and Mitchell, 2005). The most commonly studied mood symptom is depression, but other common ones

include irritability and anxiety (de Wit et al., 2021; Rössler et al., 2016; Seritan et al., 2010). Depression risk increases up to 14-fold in the 2 years surrounding the menopause transition (Schmidt et al., 2004), implicating ovarian hormone change as a trigger. Prospective longitudinal studies indicate this transition as a period of increased risk for both depressive symptoms and depressive disorders (Schmidt et al., 2004). With approximately 73 million U.S. women over age 45 (Statista, 2023), more than 1 million women reach menopause every year, and up to 70 percent will experience psychogenic symptoms associated with perimenopause and postmenopause (including anger/irritability, anxiety/tension, and depression) (NIA, 2022; Peacock et al., 2023). Depression (and anxiety) reduce health-related quality of life more than any of the other symptoms related to mental health (Wariso et al., 2017; Whiteley et al., 2013), contributing to the $326.2 billion annual cost associated with depression in the United States (Greenberg et al., 2021).

While research has shown that hormonal changes during perimenopause can affect mood, the precise mechanisms by which these fluctuations lead to depression are not fully understood, and studies are needed to elucidate the roles of estrogen, progesterone (PG), and other hormones in mood regulation during this time (Alblooshi et al., 2023; Bromberger and Epperson, 2018). In addition, factors such as stressful life events, social support, and attitudes toward aging and the menopause transition can influence the onset of depression. However, the interplay between these psychosocial factors and biological changes is not well characterized, representing a major research gap (Bromberger and Epperson, 2018). Although hormone therapy is commonly used to treat menopausal symptoms, its effectiveness as a monotherapy and use in combination with other treatments, specifically for menopause-related depression, merits more robust research (Gnanasegar et al., 2024; Maki et al., 2019). Studies on the long-term effects and safety of hormone therapy for mental health are needed as well. Without a clear understanding of the biological mechanisms driving menopause-related depression or well-powered studies to identify efficacious treatments, clinicians lack the evidence base needed to guide patient care.

FEMALE-SPECIFIC CONDITIONS WITH INCREASED DALYS RESULTING FROM EARLY MORTALITY

This section discusses female-specific cancers that are leading causes of early mortality in women and their variable progress based on NIH investment in research funding. Although breast cancer could fit in this category, it is discussed in the increased DALYs resulting from disability and early mortality section.

Uterine Malignancies

Uterine malignancies, including endometrial carcinomas and uterine sarcomas, are the most common and leading cause of gynecologic cancer. Over the past 2 decades, incidence and mortality rates for uterine cancers have risen alarmingly (Clarke et al., 2019; NASEM, 2024c; NCI, n.d.-d; Whetstone et al., 2022). It is estimated there will be 67,880 new cases and 13,250 deaths from uterine malignancies in 2024, representing 3.4 percent of all new cancer cases, with significant race-related survival disparities (NCI, n.d.-d; Siegel et al., 2024). The 5-year relative survival rate is 84 percent for White women and 63 percent for Black women (Whetstone et al., 2022).

The increasing rates of this disease, rising mortality, and alarming race-related disparities in endometrial cancer necessitate identifying and addressing research gaps (Siegel et al., 2024). Specifically, research is needed to understand the relationship between sex hormones, body weight, inflammation, environmental factors, and social determinants of health (SDOH) in disease etiology; develop prevention strategies and better diagnostic tools; and develop novel FDA-approved treatments. Prevention efforts will need to focus on balancing hormones, weight management, and physical activity (Bae-Jump, 2024). The advent of immunotherapy has seen a dramatic improvement in survival rates for individuals diagnosed with advanced disease, but an approach is lacking for identifying women most likely to benefit from these treatments (Tillmanns et al., 2024). Additional research is needed to assess and validate novel biomarkers of molecular classification to identify patients most likely to respond to therapy and elucidate resistance mechanisms for those who fail to respond to chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and the emerging antibody-drug conjugates.

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancer, collectively called “ovarian cancer,” is an often lethal gynecologic malignancy, with 19,680 new cases and 12,740 deaths anticipated in 2024 (NCI, n.d.-c). Screening and early detection of ovarian cancer are challenging, and efforts to improve that have been unsuccessful and did not reduce mortality; it is therefore most common for cancer to be in a late stage at diagnosis (Buys et al., 2011; Karlan, 2024; Menon et al., 2021; NASEM, 2024c). While the incidence and mortality rates are declining, successful cures for this lethal disease remain elusive (American Cancer Society, 2024a). The landscape of ovarian cancer treatment shifted dramatically for high-grade serous—the most common type—and endometrioid cancers with the incorporation

of maintenance poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor therapy. Since the approval of olaparib in 2018, several other PARP inhibitors have been approved to treat epithelial ovarian cancer or undergone evaluation (Coleman et al., 2017, 2019; González-Martín et al., 2019; Moore et al., 2018). Maintenance PARP inhibitor therapy for newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients improved progression-free survival significantly, with the greatest benefit seen for those with BRCA-mutated cancers, followed by those with cancer that is homologous recombination deficient (Karlan, 2024; NCCN, 2024). Identifying active treatment options for patients with non-homologous-recombination-deficient epithelial ovarian cancers and primary platinum resistant disease is an important research need (Karlan, 2024).

Specific critical gaps in ovarian cancer include screening, understanding mechanisms of resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy and PARP inhibitor therapy, identification of treatment options for patients who progress on PARP inhibitor therapy, biomarkers to better identify homologous recombination deficiency, and identification of novel therapies beyond PARP inhibitors and emerging antibody-drug conjugates. Gaps to address for rare ovarian cancers, such as nonserous epithelial cancer, germ cell tumors, and stromal tumors, which tend to occur in younger women (Al Harbi et al., 2021; Berek et al., 2021), include developing representative animal models to understand pathophysiology and guide innovative therapies.

Cervical, Vulvar, and Vaginal Cancers

Most cervical, vulvar, and vaginal cancers are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). Other risk factors include immune system suppression, long-term use of oral contraceptives, cigarette smoking, and prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol. In 2024, there will be an estimated 13,820 new cases of cervical cancer and 6,900 cases of vulvar cancer, accounting for 4,360 and 1,630 deaths, respectively (Siegel et al., 2024). The NCI “Last Mile” Initiative Self-Collection for HPV Testing to Improve Cervical Cancer Prevention Trial is assessing HPV self-collection for testing to prevent cervical cancer (NCI, n.d.-a). While this study will help address screening barriers, gaps remain regarding the multifactorial issues that negatively affect follow-up assessment of patients with abnormal screening results, access to care, and improving cure rates (NCI, n.d.-a; Rimel et al., 2022). Additional gaps in research remain regarding the role of induction immunotherapy, radiotherapy sequencing, optimal radiation therapy techniques, understanding mechanisms of resistance to immunotherapy and other novel therapies, and treatment of non-HPV-associated aggressive cervical, vulvar, and vaginal cancers.

Benefits of Funding Research on Female-Specific Cancers

There have been repeated calls to increase funding for research in gynecological cancers. As noted, uterine cancer ranks particularly low in NCI funding across a range of metrics that benchmark funding against population health impact. In 2021, for example, it ranked last in spending per YLDs and third to last in spending per YLLs. Cervical and ovarian cancer also rank below several cancers—including prostate, brain/central nervous system, and leukemia—in spending per YLL. Furthermore, although gynecologic cancers are rarer than, for example, breast, lung, prostate, and colorectal cancer and contribute to a smaller number of total DALYs and YLLs, prognosis remains poor, as quantified in recent gynecological oncology studies that measured YLL per incident case (described as “funding to lethality scores”) (Guevara et al., 2023; Spencer et al., 2019). Greater investment in treatment for gynecological cancers may therefore substantially reduce dire health consequences experienced by many people with these conditions.

The benefits of funding research for female-specific cancers are illustrated by the congressionally directed Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program (OCRP), initiated in 1997 to support high-impact, cutting-edge research to address the unmet needs in ovarian cancer (CDMRP, 2024). From 1997 to 2022, it funded 633 awards, and 2023 had 298 applicants for awards, of which 42 were funded. Over the 27 years since the inception of OCRP, ovarian cancer incidence and mortality rates have declined (NCI, n.d.-c), and it is easy to speculate that OCRP’s investment of over $496 million in ovarian cancer research was pivotal. For example, OCRP-funded studies have yielded transformative research tools, preventive tests, biomarkers to direct therapy, and novel treatments in the scientific and clinical arena. This includes several distinct novel ovarian cancer animal models; genetic testing guidelines; genetic risk test kits for RAD51D, PALB2, and BARD1 mutations; algorithms to diagnose precursor serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma lesions; companion biomarker tests to direct PARP inhibitor therapy; and novel therapies (CDMRP, n.d.).4 In contrast, lack of investment in other gynecologic cancers has coincided with rising incidence and mortality of endometrial cancer and stagnant mortality rates in cervical cancer, with disproportionately worse survival outcomes in Hispanic and non-White women and the greatest burden on Black women (NASEM, 2024c; NCI, n.d.-b,d; Siegel et al., 2024).

___________________

4 One such novel therapy is rucaparib, which received accelerated FDA approval for treating patients with BRCA-mutated recurrent ovarian cancer in 2016 and later for maintenance treatment for select patients with platinum-sensitive disease. FDA has approved it for BRCA-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (FDA, 2016).

FEMALE-SPECIFIC CONDITIONS WITH INCREASED DALYS RESULTING FROM DISABLING CONDITIONS AND EARLY MORTALITY

Breast Cancer5

Breast cancer rates have increased by approximately 0.6 percent per year since the mid-2000s, with a slightly steeper incidence in women younger than age 50. It is the most common cancer in women other than skin cancers. The American Cancer Society estimates that 2024 will have approximately 310,720 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 56,500 new cases of ductal carcinoma in situ, and 42,250 women will die from breast cancer (American Cancer Society, 2024b).

Despite significant gaps in breast cancer research, investment has significantly affected mortality rates, with striking improvements in mortality over past decades that reflect multiple moderate gains from screening and treatment improvements (Jagsi, 2024). Increased NIH funding has led to breakthroughs in early detection methods, such as improved mammography and the development of genetic testing, allowing for earlier diagnosis and intervention, as well as improved medications that reduce breast cancer mortality and recurrence (see Box 7-7). Surgical techniques have evolved from radical mastectomies to more conservative approaches, such as lumpectomies and focused and targeted lymphadenectomy, minimizing the physical and emotional impact while maintaining efficacy (Jagsi, 2024). Radiation therapy has also seen progress with more precise targeting methods, reducing damage to healthy tissue and improving outcomes. Chemotherapy has become more effective with the introduction of targeted therapies and less toxic drug regimens, allowing for more personalized and effective treatment plans (Jagsi, 2024). NIH-funded studies have advanced the understanding of how the immune system interacts with breast cancer, which has contributed to developing immunotherapeutic approaches, including checkpoint inhibitors and vaccine therapies, that are now being explored in clinical trials (Al-Hawary et al., 2023; Morrison et al., 2024; Nordin et al., 2023; Pallerla et al., 2021).

Although these investments have paid off in terms of decreasing morbidity and mortality, the journey to preventing and treating breast cancer is not over. Gaps remain in translating many of these discoveries into practice. For example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has concluded there is insufficient evidence to determine the benefits and harms of screening mammography among women aged 75 and older and of supplemental screening

___________________

5 Although breast cancer does affect men, less than 1 percent of all U.S. breast cancer diagnoses are in men (NCI, 2020).

BOX 7-7

NIH-Funded Breast Cancer Prevention and Treatment Discoveries

- In 1958, chemotherapy drugs were used at the NIH Clinical Center to treat solid tumor cancers (including breast cancer), which is now a standard treatment.

- Breakthroughs in imaging technologies (e.g., 3-D mammography) and new biomarker-based tests have improved early detection and diagnosis, allowing for earlier and more precise intervention.

- Research helped identify breast cancer subtypes based on tumor molecular features, which allows for more targeted treatments, contributing to a 41 percent decrease in death rates from 1990–2019.

- In 2012, an NIH-funded study found that a combination of two drugs can lengthen the lives of postmenopausal women with the most common type of metastatic breast cancer.

- Research that identified and characterized the BRCA gene mutations in breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancer, which allows individuals with a family history of these cancers to use genetic test results to inform decision making for screening, prevention, and treatments.

- Research has led to developing new drugs that target specific aspects of breast cancer biology. For example, aromatase inhibitors are a standard treatment for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, and CDK4/6 inhibitors have also improved treatment options for this type of breast cancer.

- NIH research led to the discovery and clinical use of drugs such as trastuzumab (Herceptin) for HER2-positive breast cancer and significantly improved outcomes for patients with this subtype.

SOURCES: Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, 2015; Morrison et al., 2024; NIH, 2013, n.d.-a; Santen et al., 2009; Ulm et al., 2019.

with ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging in women with dense breasts (USPSTF, 2024). Additionally, although robust evidence shows some women can safely avoid potentially toxic treatments, that does not always translate into practice, and many women pursue unnecessarily aggressive treatments, leading to worsened quality of life, second malignancies after unnecessary radiation, and other side effects, such as cardiac toxicity, cognitive decline, and financial toxicity (Jagsi et al., 2017; NASEM, 2024c). Additional research is needed to prevent and treat metastatic breast cancer

and to elucidate the biological mechanisms driving metastasis, including how cancer cells evade the immune system and survive in distant organs.

Racial and Ethnic Survival Disparities in Breast and Gynecologic Cancers

Significant racial and ethnic survival disparities for individuals diagnosed with breast and gynecologic cancers have been reported since the 1970s (Towner et al., 2022). Despite this knowledge, gaps in care have not been completely addressed, leading to persistent and detrimental survival disparities. Overall, the age-standardized death rate for all cancers is highest for non-Hispanic Black patients compared to all other racial and ethnic groups (Cronin et al., 2022). Survival disparities are most striking for uterine cancer, the only cancer for which mortality rates have increased over the past 4 decades (Siegel et al., 2024). Its increased incidence is most pronounced among those who identify as Black, Asian American, Pacific Islander, and/or Hispanic, with a greater than 2 percent increase since the mid-2000s (Siegel et al., 2024). The most alarming racial survival disparity is between Black and White patients; Black people with uterine cancers have a twofold increased risk of death (Siegel et al., 2024). In 2018, the 3-year survival rates were only 69.1 percent in Black patients compared to 86.5 percent in White patients (NCI, 2024d).

Conversely, since about 2000, death rates for breast and ovarian cancer have decreased, while mortality rates have remained stagnant for cervical cancer patients (Siegel et al., 2024). However, Black people with breast, ovarian, and cervical cancers also have worse outcomes compared to White people for every stage of diagnosis (Siegel et al., 2024). For breast cancer, the 3-year relative survival rates in 2018 were 94.8 versus 88.8 percent for White and Black patients, respectively (NCI, 2024a,b). Similar trends were reported for ovarian cancer in 2018, with 3-year relative survival rates of 61.5 versus 55.5 percent for White and Black patients, respectively (NCI, 2024f). For cervical cancer, Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native patients still have the highest incidence and mortality rates compared to White and non-Hispanic patients (AARC, 2024; NCI, n.d.-b; Siegel et al., 2024). Furthermore, screening tests are less likely to be obtained for Hispanic patients compared to White and Black patients (AARC, 2024). The 3-year relative survival rates for cervical cancer are 74.4 versus 64.8 percent for White and Black patients, respectively (NCI, 2024c).

Additionally, Black and Hispanic women with breast, ovarian, cervical, and endometrial cancer are less likely to receive care that adheres to current guidelines (AARC, 2024; Hinchcliff et al., 2019; Siegel et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2020a). Marginalized patient populations are also less likely to be represented in clinical trials (Scalici et al., 2015); including them is imperative to ensure improved understanding of racial and ethnic differences in

tumor biology, biomarkers, response to therapy, and survival outcomes. Cancer survivors who identify as Black and Hispanic/Latina have poorer quality of life and mental health compared to White or other racial and ethnic groups, respectively (AARC, 2024).

Research has improved understanding of the underlying molecular biology of disease. However, significant gaps remain. More research is needed to understand the underlying etiology of racial and ethnic survival disparities and intersections with SDOH. Dedicated funding to address cancer disparities for female-specific cancers are critical to mitigate racial and ethnic survival disparities and ensure equitable care for all patients.

Maternal Disorders/Pregnancy-Related Complications

Each year, there are 5.5–6.5 million pregnancies in the United States. Despite the incredibly common nature of pregnancy, its understanding along the translational science spectrum from basic science to population health outcomes and policy impact remains poor. In fact, even the precise number of pregnancies in any given year remains elusive, largely because of data collection gaps (NASEM, 2024a; Rossen et al., 2023). Pregnancy and childbirth are often relational experiences, with effects on not only the pregnant person but also partners, families, and communities.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes most often have multiple contributing factors, including genetic, epigenetic, environmental, and behavioral factors; quality of care; and structural causes. As with many health outcomes, inequities in pregnancy exist across and between multiple axes of social risk, including education, access to care, and geographic location. Data are limited on how structural drivers of health, such as racism, discrimination, classism, and sexism, manifest in the body to change biological process and impact pregnancy outcomes. However, epidemiologic data demonstrate that Black, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) mothers and infants, for example, experience two- to threefold higher rates of adverse outcomes compared to their White counterparts (CDC, n.d.-c; Hill et al., 2022; NASEM, 2020; Petersen et al., 2019). The gaps in these outcomes, which include stillbirth, low birthweight, infant mortality, and maternal mortality, have remained nearly unchanged for over a century despite medical, technical, and public health advances that have reduced overall rates. This suggests that structural factors—in this case, structural racism—play a role in distributing access to opportunities for health improvement inequitably across social axes (Hill et al., 2022; NASEM, 2019, 2020, 2023).

This section provides examples of pregnancy-related conditions for which research investment could significantly improve treatment and prevention or close gaps in maternal health morbidity and mortality. For many

of these conditions, different pathophysiologic pathways may lead to the same downstream consequences, but current scientific knowledge lacks the detail and precision to differentiate these, which also results in ineffective treatments, as heterogenous processes are often lumped together and treated similarly.

Maternal Mortality

Maternal mortality is generally defined as death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of the pregnancy, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) use the phrase “pregnancy-related mortality” to include deaths that occur during or within 1 year of the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy (CDC, n.d.-b; WHO, n.d.). In 2022, 817 people died of pregnancy-related causes in the United States, resulting in a maternal mortality ratio of 22 per 100,000 live births (Hoyert, 2024). This has earned the United States the unenviable rank of the highest maternal mortality ratio among high-income countries (Gunja et al., 2024).6 Its maternal mortality is also characterized by stark racial disparities, with NHPI, Black, and AIAN people having the highest rates (CDC, n.d.-b). In 2022, the rate was 49.5 per 100,000 live births among Black patients, which is nearly threefold higher than the 19 per 100,000 among White birthing people (Hoyert, 2024). Geographical disparities also exist, with the highest rates in Arkansas and Mississippi (CDC, n.d.-a).

A review of maternal deaths from 2017 to 2019 in 36 states showed that pregnancy-related deaths occurred during pregnancy, birth, and up to 1 year postpartum, with 53 percent occurring from 7 days to 1 year postpartum (Trost et al., 2022). Moreover, over 80 percent of these deaths were determined to be preventable (Trost et al., 2022).

The etiology of maternal mortality is multifaceted and includes direct and indirect causes. The CDC analysis showed that the six most frequent direct causes were mental health conditions (22.7 percent), hemorrhage (13.7 percent), cardiac and coronary conditions (12.8 percent), infection (9.2 percent), thrombotic embolism (8.7 percent), and cardiomyopathy (8.5 percent), accounting for over 75 percent of these deaths (Trost et al., 2022). The leading underlying cause of death varied by race and ethnicity, with cardiac and coronary conditions most common among non-Hispanic Black persons; mental health conditions most common among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White persons; and hemorrhage most common among non-Hispanic Asian people (Trost et al., 2022).

___________________

6 High-income countries have data collection, reporting, definitional, and population differences, making this comparison complex.

Indirect causes of maternal mortality include structural racism, economic inequities, public policies, such as a lack of access to insurance or parental leave, and other social drivers, including food, housing, and transportation instability, that culminate in inequities in the longitudinal provision of preconception, antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care at the system, provider, and patient levels (Crear-Perry et al., 2021; Howell, 2018). The effect of state abortion bans enabled by the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade may also affect maternal deaths. There have numerous reports and litigation on the effect of the denial of care that includes abortion or miscarriage management care to women experiencing potentially life-threatening pregnancy-related emergencies (Grossman et al., 2023).7,8,9 Research conducted before the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision found a higher likelihood of maternal mortality in states with restrictive abortion policies (Vilda et al., 2021). Recent news reports have begun to identify cases of maternal deaths that have been attributed to denial of appropriate care due to abortion bans, but initial research from national vital statistics data for the year following the decision has not noted such an effect (Stevenson and Root, 2024; Surana, 2024a,b). A landmark prospective study on the effect of abortion denial found that women who were denied abortions and who gave birth had higher rates of pregnancy-related complications, including, eclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, and gestational hypertension, compared to those who were able to obtain a wanted abortion (ANSIRH, n.d.; Gerdts et al., 2016; Ralph et al., 2019).

Gaps in maternal mortality and morbidity research include difficulties in case ascertainment for maternal mortality from death records and potential misclassification in current coding methods and systems (Collier and Molina, 2019; Joseph et al., 2024; MacDorman and Declercq, 2018; van den Akker et al., 2017). Each U.S. state may choose to participate in Maternal Mortality Review Committee efforts; a multidisciplinary committee reviews the circumstances of maternal deaths to adjudicate pregnancy relatedness and opportunities for prevention or intervention (Collier and Molina, 2019; St. Pierre et al., 2018). Funding for this remains limited, as does the ability for any central authority to combine and synthesize recommendations for prevention or intervention to develop programs to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity (St. Pierre et al., 2018). In addition, granular analyses that provide insight into community or population experience are hampered by low numbers (e.g., lack of granular race data for NHPI individuals) (Trost et al., 2022).

___________________

7 Blackmon v. State of Tennessee (2023).

8 Adkins v. State of Idaho (2023).

9 Zurawski v. State of Texas (2023).

A leading cause of maternal mortality is death from suicide or overdose—that is, perinatal mental health concerns and substance use disorders (Chin et al., 2022; Han et al., 2024). Though a monitoring framework for maternal morbidity—a harbinger of problems that, if left unchecked, could lead to maternal mortality—exists and has been validated, no similar measure of severe maternal mental health morbidity exists to help identify and target those most at risk for suicide or overdose in the peripartum period.

As noted, indirect causes of maternal mortality are important contributors, so studies that focus on the social and structural determinants of health and their effect on maternal outcomes are needed (Crear-Perry et al., 2021). Gaps also remain in understanding provider access, availability, knowledge, and potential for bias in care around maternal mortality, particularly for acute health events (Howell, 2018; NASEM, 2021; Slaughter-Acey et al., 2023).

RPL

The definition of RPL differs across professional societies.10 Based on these varying definitions, 1–5 percent of individuals attempting pregnancy will experience it, and fewer than 1 percent will experience three or more consecutive first-trimester pregnancy losses (ACOG, 2024; Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2012; Regan et al., 2023).

While embryonic aneuploidy, or abnormal chromosome number, is the most common cause of any one pregnancy loss, its contribution decreases as consecutive pregnancy losses increase. Other potential explanations include uterine anomalies, endocrine disorders, immune disorders, and thrombophilias, which are genetic or acquired blood clotting disorders (Ford and Schust, 2009; Regan et al., 2023). RPL confers significant mental, emotional, and financial burdens that affect health care costs, personal and family stress, and work productivity (Laijawala, 2024; Quenby et al., 2021). Despite these burdens, it remains unexplained in 50 percent of cases (ACOG, 2024; Ford and Schust, 2009). Furthermore, no treatments have consistently demonstrated effectiveness in maintaining pregnancies afterward. This is true even for interventions, including uterine septum resection and PG supplementation, aimed at specific relevant etiologies (Ford and Schust, 2009; Regan et al., 2023).

___________________

10 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for example, defines RPL as having two or more miscarriages, while the American Society of Reproductive Medicine defines it as the loss of two or more clinical and consecutive pregnancies with either ultrasound or histopathological documentation, excluding ectopic and molar pregnancies, and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists defines it as three or more consecutive first trimester miscarriages (ACOG, 2024; Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2013; Regan et al., 2023).

Recent early trials for subsets of the RPL population have shown some promise. For example, intravenous immunoglobulin IVIG for individuals who have experienced more than four losses and PG supplementation for individuals with more than three losses and vaginal bleeding in the first trimester of a subsequent pregnancy may show promise for these small subsets, but their evidence base and effectiveness in practice remains under investigation given the lack of large-scale, randomized controlled trials and conclusive evidence (ACOG, 2021; Banjar et al., 2023; Coomarasamy et al., 2019, 2020; D’Mello et al., 2021; Habets et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2022; Yamada et al., 2022).

The failure of many proposed treatment strategies is likely due to several heterogenous disease processes that result in a similar clinical phenotype of RPL. Therefore, the entire relevant translational research spectrum would benefit from increased attention; it serves as a clear example of gaps in basic science knowledge. Understanding is limited of the processes that support appropriate implantation and permit early pregnancies to progress when the embryo has normal genes. This inadequate understanding of pathophysiology across both identified and yet-to-be-identified causes of RPL has generally hampered progress toward interventions that could mitigate the substantial emotional, financial, and potential long-term health burdens (Laijawala, 2024; Quenby et al., 2021).

Preeclampsia

Preeclampsia is on a spectrum of hypertensive diseases in pregnancy and affects 2–8 percent of all pregnant people globally (ACOG, n.d.). Classically, pregnant people are diagnosed when they exhibit new-onset elevated blood pressures and proteinuria, or elevated protein in the urine, beyond 20 weeks of pregnancy. More severe forms manifest with pulmonary edema, cardiomyopathy, seizures, uncontrolled headaches, or end-organ damage, such as acute liver or kidney injury. Preeclampsia and other related hypertensive disorders of pregnancy significantly affect maternal and fetal health, with more than 7 percent of maternal deaths stemming from preeclampsia and its complications (CDC, 2022).

In addition, preeclampsia drives a significant proportion of preterm births (PTBs) resulting from the need to induce birth early for maternal safety and from small for gestational age neonates due to associated poor placental function. Black and African American pregnant people in the United States have a moderately increased risk of preeclampsia compared to White individuals and a higher likelihood of related morbidity and mortality, suggesting differences in treatment and care access (MacDorman et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020b). Preeclampsia confers lifelong increased cardiovascular risks that compound its health effects and underscore the urgency of understanding, treating, and preventing it and its long-term consequences.

The origins of preeclampsia are not fully understood but likely begin with impaired placental implantation (Dimitriadis et al., 2023; Huppertz, 2008; Kalafat and Thilaganathan, 2017; Kornacki et al., 2023). Advances in understanding the roles of serum markers that indicate dysfunction within the lining of small blood vessels and markers of immune system dysfunction have not yet translated into improved diagnostic or therapeutic options (Amaral et al., 2017; Dimitriadis et al., 2023; Jung et al., 2022). Preeclampsia remains a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms and signs consistent with it; diagnosis is challenging when other comorbidities exist that mimic these, such as chronic hypertension and autoimmune disease (Jung et al., 2022; Staff, 2019). The lack of a definitive diagnostic disease marker increases the potential for bias in interpreting the signs and symptoms by race, ethnicity, or other demographics, thereby increasing the possibility of inequitable outcomes (Dimitriadis et al., 2023; Johnson and Louis, 2022).