A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health (2025)

Chapter: 2 The Need for Women's Health Research

2

The Need for Women’s Health Research

INTRODUCTION

This chapter details the many compelling reasons for the nation’s research enterprise to prioritize women’s health. During its review, the committee identified a clear need for additional funding for women’s health research (WHR). However, this need may not be self-evident, as some may point to the existence of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) and its successes as an indication that WHR has been prioritized sufficiently. However, decades after NIH established ORWH, several lines of evidence suggest WHR remains underfunded and clinical outcomes for women lag behind men. Women represent 50.5 percent of the U.S. population, and although they live nearly 6 years longer than men, they live longer in poor health and with higher rates of disabilities (Census Bureau, n.d.; Di Lego et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2024).

This chapter illustrates how the factors outlined later in this report—research gaps and social and biological factors—underscore the urgent need for addressing WHR. It describes the centrality of women’s health to a healthy society, the exclusion and subsequent underrepresentation of women in health research, the benefits of WHR for the entire population, why female biology requires sex-specific research, and examples of funding opportunities for conditions that are female specific, are more common in women, or affect women differently.

HEALTHY WOMEN ARE VITAL TO A HEALTHY SOCIETY AND GROWING ECONOMY

Women represent 50.5 percent of the U.S. population and 56.8 percent of the workforce, with their participation in the workforce serving as a key driver of entrepreneurialism and economic growth (BLS, 2023; Bovino and Gold, 2018; Census Bureau, n.d.). Those assigned female at birth are solely responsible for gestation, childbirth, and lactation and the majority of the unpaid caregiving roles in society, including caring for children and older adults (Stall et al., 2023). The health, longevity, and well-being of women is critical to well-functioning families, the U.S. economy, and society at large.

Conditions that are female specific or more common in women affect women’s ability to fully participate in society. For example, 10 percent of U.S. menopausal women reported missing work because of menopausal transition symptoms in the past year, which accrued to $1.8 billion in lost days of work (Faubion et al., 2023). Similarly, individuals with recurrent migraines, a condition more common in women than men and most common in women of childbearing age, are more likely to miss work and to do so for extended periods than those without migraine (Bonafede et al., 2018a; Burch et al., 2021). Migraine is estimated to cost employers $13 billion per year resulting from missed workdays and impaired work function (Hu et al., 1999). One study found that approximately 40 percent of adults with migraine were unemployed and 18 percent had no health insurance (Burch et al., 2021). See Box 2-1 for input from a patient regarding how migraines have affected her life.

Women are also more likely than men to engage in volunteerism, through which they contribute to social services, education, and health initiatives (Brown, 2020). Women are essential to the health care workforce. More women than men are nurses, doctors, and other health care workers (Cheeseman Day and Christnacht, 2019). Women also serve as the chief medical officers of their homes, promoting healthy behaviors and ensuring that family members access medical care (Williamson, 2024). Women are overrepresented in the education workforce and so play a critical role in educating the next generation (Superville, 2023). Considering women’s central roles to both the workforce and families, research investments to improve women’s health, and thereby reduce disability, stand to have a large economic impact (Baird et al., 2021).

WHR: STILL OVERLOOKED, UNDERSTUDIED

The inclusion of women as participants in health research and the study of female animals and tissues have evolved over the past few decades. During the 1970s, few women worked in medicine or science, and women’s

BOX 2-1

Excerpts from a Patient Advocate During Public Comments at a Committee Meeting

I started getting migraines when I was five. I only got one or two a year until I was 13. At age 13, I got migraines every day. At age 16, I became debilitated every day until I was 22. From 16 to 22, I was either hospitalized. . . . for inpatient IV therapy or outpatient 3-day IV therapy. Then, from that time, once I went through puberty, things slowed down, but since that time, my migraines are still more than 15 days per month, which is what a normal migraine patient would have. In addition to having normal pain migraines, I also have migraines that have brainstem aura, and I become fully paralyzed. I also have allodynia, which is like having a migraine on my skin.

Most migraine research is done on White males who are of an upper socioeconomic class, however one in five women get migraines. It’s much more prevalent in women. And so, that is what I’m asking for, is more migraine research for women, and across racial and ethnic groups . . . and rural regions as well. Native and Indigenous people have the highest prevalence of migraines and severe headaches in the United States.

I grew up in a very rural community. That was part of the reason why it took so long for me to be able to get help. I had to drive 3 hours away in order to get headache access care. And this was back in the ’90s. So, one of the things we definitely need to have is better headache research on how to train doctors and nurse practitioners on how to work with migraine patients.

health was a low priority in both the scientific and medical fields (ORWH, n.d.-b). Adult male anatomy and physiology were the primary focal point of the study of human health, and women were usually excluded from clinical research studies over concerns about potential risks to fertility and pregnancy and the variability of ovarian hormones and the menstrual cycle. These concerns reflected societal interests in protecting vulnerable populations, which emerged at least in part from discoveries of birth defects resulting from fetal exposure to certain drugs, including thalidomide and diethylstilbestrol (FDA, 2018; ORWH, n.d.-b). Responding to possibility of fetal harm from experimental drug research, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a 1977 guideline excluding “any premenopausal female capable of becoming pregnant” from participating in Phase I and early Phase II clinical trials (FDA, 2018). Inherent in this guidance was the assumption that women cannot avoid becoming pregnant, that potential

risks to fertility and the fetus supersede the benefits to women of participation, and that it is acceptable to refrain from building an evidence base from which to care for women whether or not they are pregnant.

The Belmont Report, published by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research in 1977, advanced the conviction that the autonomy of individuals should be respected (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979). Scientific, policy, and advocacy communities raised concerns about the practice of excluding women with childbearing potential from research regardless of their desire to participate or the relative potential benefits (IOM, 1994; ORWH, 2021, n.d.-b). Women’s health organizations protested this exclusion, stating the FDA guidance had a chilling effect on including women in later-phase clinical trials and prevented women with life-threatening diseases from participating in early-phase trials, regardless of its explicit exception for these circumstances (BLS, 1973; FDA, 2018; IOM, 1994; Liu and Mager, 2016). Despite these concerns, FDA did not explicitly reverse its recommendation until 1993 (FDA, 2018). The new guidelines it issued called for investigators to analyze clinical data to assess the effects of sex on clinical outcomes and highlighted the growing recognition that medications may need to be dosed or administered differently for women (Liu and Mager, 2016).

Simultaneously, NIH was considering policies regarding the inclusion of women in research. Since the establishment of ORWH and the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993, which directed NIH to develop guidance on including women and racially and ethnically minoritized populations in clinical trials, representation of women has improved (Liu and Mager, 2016; ORWH, n.d.-b; Sosinsky et al., 2022). Girls and women made up 57.2 percent of enrollment in NIH-defined clinical research in fiscal year 2014 (ORWH, n.d.-a). However, underrepresentation persists among certain disciplines and conditions, and, among women, pregnant and lactating individuals, sexual- and gender-minority populations, and some racial and ethnic groups remain underrepresented in clinical trials. Moreover, even when research has included underrepresented groups, investigators have not conducted, reported, or published results and analyses specific to these groups (NASEM, 2022, 2023b; Sosinsky et al., 2022).

This history of exclusion is central to understanding the extensive gaps in the evidence base on women’s health and the rationale for prioritizing WHR now. Because research conducted in men was assumed to generalize to women and women were viewed as a vulnerable population, systematically excluding them from biomedical research was seen as protective and assumed not to create significant barriers to their health and health care. However, this assumption has turned out to be incorrect in many ways. One striking example is cardiovascular disease (CVD). Early research on heart attack

symptoms was based on male participants, which led to a focus on chest pain as the cardinal symptom. Women, however, are less likely than men to experience chest pain and more likely to have other symptoms, including shortness of breath, nausea, and pain between the shoulder blades during a heart attack (van Oosterhout et al., 2020). Differences in symptom presentation have led to misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis of heart attacks in women, delayed treatment, and worse outcomes. Thus, the weaker evidence base on CVD in women, and differences in male and female physiology and disease course, have confounded care in women (Keteepe-Arachi and Sharma, 2017).

Pharmacologic responses to medications represent a second example of how research conducted in male participants may not generalize to females. Because many drugs were originally tested solely on male participants, dosing recommendations did not account for sex differences in how the body metabolizes different drugs (Courchesne et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2023; Soldin and Mattison, 2009). While one medication, the sleep medicine zolpidem (Ambien), has different dosages for men and women, this dosage is not necessarily supported by scientific evidence (Greenblatt et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2023). Additional evidence-based research is needed to determine which sex differences in drug metabolism are linked to differences in clinically significant outcomes.

Depression treatment is another example of lack of generalizability from men to women. Although depression is twice as prevalent in women than men and certain reproductive-related hormone changes, especially during and after pregnancy, place women at increased risk of depression, antidepressant clinical trials historically underrepresented women or did not study sex differences and excluded pregnant women (Lee et al., 2023; Soares and Zitek, 2008; Trost et al., 2022; Weinberger et al., 2010). Perinatal depression, for instance, affects more than 15 percent of women and, along with other mental health conditions, is the leading cause of maternal mortality, accounting for 23 percent of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States (Dagher et al., 2021; Payne and Maguire, 2019; Sayres Van Niel and Payne, 2020; Trost et al., 2022).

In the United States, antidepressant medications are more accessible and affordable than other forms of treatment, including psychotherapy, so many women are prescribed these during pregnancy and lactation. Yet, because pregnant women were excluded from the clinical trials, physicians have been left to weigh the risks and benefits based on epidemiologic and observational studies that are considered less compelling and conclusive and offer a lower level of evidence and confidence for informing clinical decisions. Many physicians abruptly stopped antidepressants for women who became pregnant or refused to treat depression in their pregnant patients, causing acute psychiatric crisis. This practice and associated concerns about legal liability continues today (Coffman and Ash, 2019; NASEM, 2023b).

The early underrepresentation of women in mental health research has also affected the management of depression during perimenopause and postmenopause. Drugs in the most common class of antidepressant medication, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), were tested primarily in men but prescribed to women across the reproductive life-span. More recent research has shown, however, that SSRIs work less well in women over age 50. Adding estrogen therapy to SSRI treatment appears to restore its efficacy, though many women are ineligible for estrogen therapy because of their age and other health conditions. Moreover, this “solution” has only been tested in small clinical studies (Thase et al., 2005), pointing to the need for research to establish best practices in caring for women experiencing depression over the female life course (Cho et al., 2023; NAMS 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel, 2022).

These and many other gaps in knowledge about women’s health fail women and their health care providers, who cannot provide informed care to the degree they can for men. Of the female-specific conditions, gynecologic conditions, such as endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, and premature ovarian insufficiency, generally require a chronic management approach, yet physicians lack clear guidance and state-of-the-art tools to address these costly and debilitating conditions (NASEM, 2024a).

The gaps in women’s health research are large and at times feel overwhelming. My personal experiences are exacerbated by the frustrations of not being able to help my patients in more meaningful ways, by witnessing my peers and their daughter(s) suffering from so many gynecological conditions that remain with the same ineffective treatments that I offered to patients as an OB/GYN resident over 30 years ago.

—Participant at committee information-gathering meeting

In summary, the medical research gap in gender- and sex-based differences is multifactorial, attributable in some part to sexism, the relative complexity of female physiology, and persistent lack of prioritization of women’s health by researchers and the institutions in which they work (Galea et al., 2020; IOM, 2010; Plevkova et al., 2020). The specific examples provided here are merely three among many. However, progress in science is made by building new avenues of investigation on the foundation of existing knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and disease. Many areas of science fail to appreciate the missed opportunities for breakthroughs caused by exclusion of women or female animals and whether the basic understanding of anatomy, physiology, or disease is correct when applied to them (see Chapter 5 for more information). The historical exclusion and subsequent underrepresentation of women in health research and the lack of focus on both sex-specific and non-sex-specific aspects of women’s health have limited the

understanding of human development, health, and disease and systematically created gaps in knowledge of conditions that are female specific, are more common in women, or affect women differently, including their diagnosis and treatment (Galea et al., 2020; Temkin et al., 2022, 2023).

Unfortunately, including female research participants has not been accompanied by systematic efforts to understand diseases in women—that is, such inclusion alone is insufficient for progress. The range and nature of basic development of female physiology, wide-ranging effects of hormones, and types of chronic diseases and conditions prevalent in women are still poorly understood. As a result, work that includes women is often largely informed by theories and measures that were developed by studying men. This work often continues to rely on the assumption that research findings would be generally similar among women, as though they were smaller versions of men, or that any significant differences would somehow have been identified already. In other words, current research often assumes that past limitations in science no longer affect the quality or applicability of today’s findings. Unless these assumptions are systematically discarded, scientific breakthroughs in women’s health remain stalled.

Today, research focused on conditions and illnesses that only affect women, are more common in women, and progress differently in women, are lagging and lacking (Temkin et al., 2022, 2023). These knowledge gaps translate into missed opportunities to prevent, diagnose, and treat many conditions and avoid prolonged suffering, disability, or death. As a result, gaps in the evidence base on women’s health drive up the costs of care; increased funding to address these gaps can produce a striking return on investment for society as a whole in terms of improved outcomes, savings in health care expenditures, and reductions in potential years of labor force participation lost to disability (Baird et al., 2021).

INTERSECTING BARRIERS TO HEALTH CARE

Substantial barriers, including economic, geographic, institutional, social, and cultural barriers, discrimination and bias, lack of education and health literacy, and stigma, prevent women from accessing and receiving appropriate, acceptable, and effective health care (Long et al., 2023; Vohra-Gupta et al., 2023). While each of these barriers also affect men, they have a different effect on women, and they adversely affect health.

The high cost of health care in the United States is a significant barrier. Costs include insurance premiums, deductibles, and out-of-pocket expenses. Twenty-eight percent of women, compared to 21 percent of men, report they delayed or went without needed care because of the cost (Lopes et al., 2024). Twenty-seven percent of women aged 18–64 report they or a household member had trouble paying medical bills in 2022, compared with

23 percent of men; this includes 42 percent of women who were uninsured, 32 percent each of Hispanic and Black women, and 42 percent of women who report being in fair or poor health (Long et al., 2022). Women aged 19–64 with employer-sponsored coverage experience higher annual out-of-pocket health care costs than men, even when excluding maternity claims, totaling $15 billion more per year; women also derive less actuarial value from each dollar spent on health care premiums (Deloitte, 2023).

Systemic and institutional barriers to care include the shortage of health care providers, lack of workforce diversity, complexity of the health care system, and administrative burden associated with health care (NASEM, 2023a, 2024b). The shortage of health care providers such as primary care physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists is well documented and differentially affects women (AAMC, 2024; Raman and Cohen, 2023). Furthermore, structural care issues and the lack of diversity in the health care workforce also lead to disparities in care, particularly for racially and ethnically minoritized women and those belonging to marginalized groups adversely affected by discrimination, cultural misunderstandings, and language barriers (Chambers et al., 2022; Chauhan et al., 2020; Lange et al., 2017; Prather et al., 2016; Salsberg et al., 2021; Shamsi et al., 2020).

Systemic racism and discrimination, compounded by social and cultural barriers to health care, result in persistent disparities in treatment and outcomes for racially and ethnically minoritized women. Providers’ implicit bias leads to poor care access and quality (Chambers et al., 2022; Prather et al., 2016). Black women continue to experience increased risk for pregnancy-related adverse events, including mortality, compared with their White counterparts (Liese et al., 2019; Prather et al., 2016). A recent systematic review demonstrated that a combination of implicit biases, race-based assumptions, and lack of cultural competence in maternity care and medical treatment is associated with adverse birth outcomes for Black women (Montalmant and Ettinger, 2024). Black women are less likely than White women to receive epidural analgesia during labor, be assessed for pain and receive pain treatment after cesarean delivery, and receive episiotomies to reduce the risk of painful vaginal and perianal ruptures (Badreldin et al., 2019; Friedman et al., 2015; Glance et al., 2007; Guglielminotti et al., 2024; Johnson et al., 2019).

Discrimination adversely affects cisgender lesbian and bisexual women and transgender people in a variety of ways (Gioia and Rosenberger, 2022). A recent study reported that 18 percent of LGBTQ adults avoided health care because of anticipated discrimination, including 22 percent of transgender adults (Casey et al., 2019). Trans-identified people and bisexual people were about two times as likely to report an unmet need for mental health care compared with cisgender heterosexual women (Steele et al., 2017). Thus, adverse consequences of health care discrimination faced by these communities contribute to poorer health outcomes, which then go untreated because of fear of discrimination, making for a vicious cycle.

Stigma is another barrier to care that affects health outcomes differently in women because of variations in societal roles, health behaviors, and the types of stigma focused on women. Women face stigma related to mental health issues and substance use, and those experiencing either issue are often perceived as neglectful or irresponsible mothers (Dennis and Chung-Lee, 2006; Nichols et al., 2021; Schofield et al., 2024). Women also face stigma regarding reproductive health issues, including seeking sexual health services, undergoing abortions, and dealing with infertility (Cutler et al., 2021; Öztürk et al., 2021; Valentine et al., 2022). Finally, women are more likely to experience weight-related discrimination and stigma than men, with women at higher weights reporting they experience more discrimination, including medical discrimination (“denied or provided inferior care”), at higher rates than men (45 vs. 28 percent) (Puhl et al., 2008).

Identifying new ways to overcome the disproportionate effect of the systemic and intersecting barriers to health care women experience is an important area for NIH research investment. The structural barriers to health care that NIH-funded research needs to address include employing implementation science to identify ways to overcome economic and geographic barriers to care, including high-quality telehealth services; developing novel service delivery methods to promote collaborative, coherent women’s health care across the life-span; identifying evidence-based strategies to reduce stigma and discrimination; and engaging in community-led research to improve the acceptability of treatment alongside efficacy. This research has the potential to not only directly affect and improve women’s health and well-being but also increase their overall contributions to productivity in the workplace and at home.

However, this research needs to be effectively translated into practice, with new findings communicated to relevant medical associations and other organizations so they can inform medical guidelines, physician decision making, and policy. One striking example of evidence not being translated is the failure of primary care physicians and internal medicine specialists to incorporate clinical science about women’s heart disease into screening and other healthy heart activities (Bairey Merz et al., 2017; Garcia et al., 2016; Isiadinso et al., 2022). NIH has a crucial role in actively disseminating such results, beyond providing the data on its website. NIH could engage with medical journals and associations and facilitate discussions and collaborations to ensure that the latest research informs clinical practice and guidelines. It could also offer enhanced grant support to enable researchers to disseminate their findings more effectively. This could include funding for translating research into lay language, covering open access publication costs in journals, hosting webinars, and supporting other outreach activities to facilitate greater understanding and engagement with the research.

BREAKTHROUGHS IN WOMEN’S HEALTH BENEFIT EVERYONE

Studying sex differences and women independently of men has led to an improved understanding of health for everyone. Two examples of breakthroughs in women’s health that benefited men are bone health and cancer treatment (Chapter 5 provides more information on both). One additional research area that holds great promise for men’s health is longevity.

Bone Health

Women experience bone loss earlier than men due to changes in hormone levels during the menopause transition (Karlamangla et al., 2021). The porous component of bone that gives bones their strength is what most rapidly declines with age. Thus, as bone loss proceeds, women are at higher risk of fractures, which are associated with premature mortality and significant morbidity and disability, including loss of independence (Kling et al., 2014; McPhee et al., 2022); a nonhormonal class of medications called “bisphosphonates” were developed and approved by FDA to prevent bone loss in women (Karlamangla et al., 2021). Additional research on the mechanisms by which bisphosphonates prevent bone loss resulted in the development of two additional classes of medications and increased knowledge to guide evidence-based screening for bone loss in women. Findings from the studies in women were then tested in men. Based on studying how men did not experience the rapid loss experienced by women during the menopause transition, current guidelines recommend waiting until age 70 to screen men for osteoporosis, if no risk factors are present (Adler, 2000; Bello et al., 2024). Thus, medications developed to combat bone loss in women also benefit men, and surveillance guidelines based on research on women were adapted for men’s unique bone loss timeline (see Chapter 5 for more details).

Cancer Treatment

After women undergo surgery for early-stage, estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer, they receive hormone therapy to prevent it from returning. One type, aromatase inhibitors, prevents the body from making estrogen, which is important in the growth of breast cancer (Chumsri et al., 2011). However, just as in the first example of the menopause transition causing bone loss, estrogen depletion caused by aromatase inhibitors causes bone loss, placing women at higher risk of fractures, and research identified nonhormonal treatments to maintain bone health. The American Society of Clinical Oncology set forth recommendations for assessing and preserving bone health for women treated with anti-estrogenic therapies in 2003

(Hillner et al., 2003). Seventeen years later, once testosterone-depleting treatments became the standard of care for prostate cancer, these screening and treatment standards, so well established in women’s health, were applied to men (Saylor et al., 2020).

More recently, a new class of medicines, poly(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, were developed to treat metastatic ovarian cancer with BRCA mutations in women (Wang et al., 2023). These drugs are effective at reducing cancer progression (MD Anderson Cancer Center, 2023; Taylor et al., 2021). Research examined whether PARP inhibitors could be used to treat breast cancer, and FDA has approved two for breast cancer with BRCA mutations (Robson et al., 2017). These discoveries have also benefited men with BRCA-mutated prostate cancer, and PARP inhibitors, either alone or in combination with other agents, are now used for certain prostate cancers, including those with BRCA mutations (Drew, 2015).

Taken together, these examples demonstrate how studying female-specific physiology and disease can lead to breakthroughs in the understanding of disease mechanisms and help identify new treatments for women. However, these examples also highlight how the breakthroughs that emerge from female-specific research can be tested in male-specific diseases to determine their relevance, thereby benefiting males as well.

Longevity

Although U.S. women generally live in poorer health and with more pain than men, they live 6 percent longer than men. Across nonhuman mammalian species, females live over 18 percent longer than males in the wild, suggesting that sex differences in longevity are at least in part related to biology (Lemaître et al., 2020). Recent research has begun examining the mechanisms contributing to longevity in women compared with men. Some hypothesize that sex chromosomes may be a cause, such as via X-linked mitochondrial inheritance, although these theories are under investigation (Hägg and Jylhävä, 2021). Others hypothesize that sex differences in longevity are related to differences in sex hormones (Hägg and Jylhävä, 2021). For example, castration (and associated testosterone withdrawal) is associated with longer male life-span; however, in mid-life and older men, lower circulating testosterone levels are associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality (Muehlenbein et al., 2022). In women, greater exposure to estrogen across the life-span (measured as a longer reproductive life-span, endogenous estrogen exposure, or total estrogen exposure) was associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular events, which in turn, is related to longer life-span (Mishra et al., 2021). Despite these potential lines of evidence, mechanisms explaining the longer life-span in women (and nonhuman

female mammals) has not been clearly identified. Research identifying the mechanisms underlying extended longevity in women may unlock new approaches to extending the life-span for both women and men.

FEMALE-SPECIFIC BIOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY

As described in more detail in Chapter 5, certain biological factors—chromosomes and hormones—determine sex and sex characteristics. Differences begin at conception with the sex chromosomes, with most female fetuses having two X chromosomes and most male fetuses having one X and one Y chromosome. To prevent a double dose of X chromosome effects in females, one of the X chromosomes is silenced in every cell in the female body through a variety of mechanisms that have an effect on women’s health (Lu et al., 2020).

Most chromosomal research has focused on the Y chromosome (see Chapter 5), and as a result, the effects of X-silencing on women’s health are only beginning to be understood. In addition, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which provide a way to compare the DNA of thousands of people to identify genetic markers for a disease, have typically excluded sex chromosomes (Dou et al., 2024; Lu et al., 2020). To capture the full potential of these methods to identify genetic markers of health and disease in both women and men, it will be essential to include sex chromosomes in GWAS. Some researchers are now beginning to appreciate the need to study these differences, and animal studies have revealed that a protein responsible for X-silencing interacts with myriad other proteins to drive autoimmune diseases more common in women (Dou et al., 2024). This recent breakthrough underscores the role of basic science in helping to explain the disproportionately high number of women compared to men who suffer from autoimmune disorders. Discovering the role of X-linked proteins in contributing to autoimmune disorders may lead to discoveries in other conditions as well.

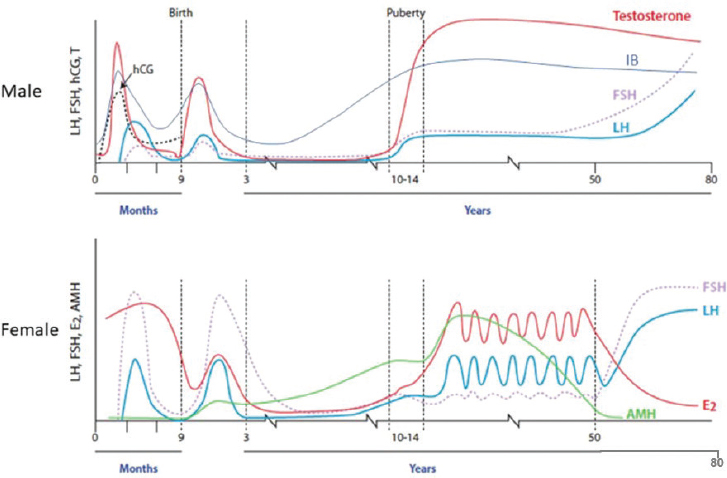

Fully understanding the biological mechanisms that cause diseases that affect women requires a more extensive understanding of female physiology, which is more dynamic because of hormonal fluctuations during the reproductive life-span. Understanding the complexity of normal physiology in females can help inform how such natural fluctuations contribute to physical and mental health. During puberty, the ovaries mature and begin producing the hormones estrogen and progesterone (Bulun, 2016). Hormonal changes cause the development of secondary sex characteristics, including breasts, ovulation, and menses. Simultaneously, the adrenal glands produce more adrenal hormones, including testosterone (Bulun, 2016). As puberty progresses, ovarian hormone release begins to follow a daily and monthly pattern, the menstrual cycle. As shown

NOTES: Circulating concentrations of gonadotropins (hCG, FSH, LH), testosterone, and inhibin B during the prenatal and postnatal period in male individuals (top panel), and gonadotropins, estradiol, and anti-Müllerian hormone in female individuals (lower panel). AMH = Anti-Müllerian hormone; E2 = estradiol; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; hCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; HPG = hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal; IB = inhibin B; LH = luteinizing hormone; T = testosterone.

SOURCE: Adapted from Howard, 2021; licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en).

in Figure 2-1, the hormonal changes of female puberty are distinct from those of male puberty (E2 is estradiol, a form of estrogen that varies regularly during the reproductive years) (Bulun, 2016). Many other hormones also follow predictable patterns during the female reproductive life-span in ways that are distinct from hormone changes in men. All organ systems have receptors for female sex hormones, so they powerfully regulate female physiology (Bulun, 2016).

These patterns continue throughout a woman’s life until she becomes pregnant or postmenopausal. During pregnancy, the cyclic pattern of change in these hormones stops, and a different pattern emerges (see Figure 2-2); estrogens have multiple roles across many organ systems, including increasing blood flow to the developing fetus, preparing the breasts for lactation, changing metabolism, regulating the cardiovascular system, and modulating the immune system (Delgado and Lopez-Ojeda, 2023; Mauvais-Jarvis et al., 2013). Thus, the effects of estrogen across multiple biological systems are

SOURCE: Kohl et al., 2017; licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en).

necessary to sustain pregnancy, trigger childbirth, and support lactation. While Figure 2-1 does not show the lifetime hormonal patterns for progesterone, that plays a critical role in the menstrual cycle and maintenance of pregnancy (see Figure 2-2), as detailed in Chapter 5.

Menopause marks the end of cyclical menstrual periods resulting from the loss of ovarian function and the end of the reproductive phase of the female life course; the final menstrual period can only be determined retrospectively after 1 year without menses (El Khoudary et al., 2019; Harlow et al., 2012). The menopause transition may occur naturally from aging, as ovaries stop producing eggs and ovarian secretion of estradiol becomes erratic, declines, and then stabilizes at a lower level postmenopause (El Khoudary et al., 2019; Harlow et al., 2012). Declining estrogen levels during this transition, either naturally or prematurely from surgical removal of the ovaries or some drugs used to treat cancer, are associated with a variety of symptoms, including hot flashes, night sweats, bone loss, insomnia, depression, vaginal atrophy and dryness, and weight gain. In addition, the menopause transition is associated with increased risk of Type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, musculoskeletal symptoms, and cardiovascular disease (Bulun, 2016; Jiang et al., 2019; OASH, 2023; Opoku et al., 2023). The health changes and variety of biological systems affected by the hormonal changes of the menopause transition provide more evidence of the powerful regulation of female physiology by ovarian hormones. Chapter 5 discusses hormonal changes from puberty to postmenopause and their regulation of female biological systems in greater detail.

The field does not know a great deal about how hormones affect health outcomes in females, but studies have shown, for example, that ovarian hormones regulate depression in women across the reproductive years. Fifty-seven percent of adolescent girls (vs. 29 percent of adolescent boys) and 24 percent of women experience depression each year in the United States, and women are about twice as likely as men to do so (CDC, 2023; Lee et al., 2023). This increased risk begins during puberty and persists through the menopause transition, coinciding with ovarian secretion of hormones. Research suggests that ovarian hormone instability during puberty, combined with the stress of adolescence, triggers depression in girls.

Hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle trigger emotional and behavioral changes in some people. Individuals with premenstrual dysphoric disorder, for example, have severe symptoms occurring in the week before menses triggered by changes in estradiol and progesterone levels (Eisenlohr-Moul, 2024). Similarly, research that administered and then withdrew pregnancy-level doses of estrogen and progesterone to women with a history of postpartum depression showed that these hormone changes alone, absent the stress of childbirth and parenting, triggered depression (Bloch et al., 2000). Finally, research on the hormonal changes of peri- and postmenopause has shown that depression symptoms begin as estrogen levels decline during the transition, and short-term treatment with estrogen reverses them (Schmidt et al., 2000). However, recent scientific advances in the understanding of how hormones may regulate mood across the reproductive life cycle have not yet translated into novel treatments or improved access to clinical care, except for perinatal depression. Chapter 5 offers more information about hormone regulation of mood and the need for new treatments and improved access to existing treatments.

In summary, understanding of women’s physiology is still limited because of insufficient research specifically focused on how women’s bodies function differently from men’s. This gap in knowledge means that many aspects of women’s health and how women’s bodies respond to various conditions and treatments are not well understood. Without well-funded, sustained efforts that focus on women and female model systems, the hormonal and chromosomal contributions to disease pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets in improving human health represent a missed opportunity.

SYNERGISTIC IMPACT OF BIOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL FACTORS ON WOMEN’S HEALTH

Research often examines biological and social factors influencing women’s health in separate studies. However, investigators have begun examining the complex interplay between the biological, social, and environmental

factors that shape biology, health, and disease. For example, social and environmental factors have been shown to account for as much as 50 percent of the variability in health outcomes for both women and men, so they are powerful determinants of health (Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014; Magnan, 2021; Whitman et al., 2022; WHO, n.d.). Menarche and the menopause transition provide clear examples of these interacting forces. For example, data suggest that age of menarche may be influenced by social and environmental factors, such as race, ethnicity, financial instability, family stressors, and nutrition (Srikanth et al., 2023; Yermachenko and Dvornyk, 2014). Similarly, social and environmental factors, such as chronic stress, trauma, and early life adversity, are associated with differences in age of menopausal transition onset and symptoms (Cortés and Marginean, 2022). Race is also a factor; compared with White women, Black women in the United States transition to peri- and postmenopause earlier and experience worse symptoms, including hot flashes, depression, and sleep disturbances (Harlow et al., 2022).

Black women are also 3 times more likely than White women to have fibroids, benign growths of uterine muscle that cause excessive menstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, and poor quality of life (Eltoukhi et al., 2014; Marsh et al., 2024). In the United States, fibroids account for over 30 percent of all hysterectomies and up to $9.4 billion in annual health care costs (Bonafede et al., 2018b; Eltoukhi et al., 2014). Rates of inpatient hospitalization for fibroids are highest during the years women begin the menopause transition, ages 40–49. Over 80 percent of Black women experience fibroids by age 50, and over 50 percent of them have fibroids that are clinically significant (they affect quality of life or require treatment) (Eltoukhi et al., 2014). While the source of the increased risk for developing fibroids is unclear, they are thought to be driven by ovarian hormones, genetics, and impaired wound healing. The latter is a hallmark symptom of exposure to both chronic and acute stressors, both from stress’s effects on the immune system and the adoption of health-damaging coping behaviors (Gouin and Kiecolt-Glaser, 2011). Because of structural inequities, Black women in the United States are exposed to more stressful and traumatic life experiences than White women and show increased stress hormones following stress exposure (Harlow et al., 2022; Schreier et al., 2016). Thus, while the racial disparity in fibroid incidence is commonly thought to be solely driven by biological factors, the interaction of social and biological factors likely plays a major role.

Furthermore, Black women are more likely to experience comorbid health conditions, including diabetes and heart disease, that are exacerbated by ovarian hormone shifts during the menopause transition (Harlow et al., 2022; Still et al., 2020). Simultaneously, they experience significant disparities in health care, including less access to care, less timely access to care,

and care discrimination (Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014; Okoro et al., 2020). Thus, the increased pain and burden of illness in Black women during the transition to menopause are met with a lower likelihood of receiving treatment and poor pain management.

These are just some examples among many of the complex interaction of biological and social factors in women’s health outcomes. Similar examples exist for Latina and American Indian or Alaska Native women and women whose bodies do not conform to social expectations for weight and gender expression and those who are immigrants, have differences in physical abilities, are neurodivergent, suffer with mental illness, or have lower socioeconomic status. All of these factors can intersect with racism, sexism, and one another to create unique biological and social interaction effects on health (NASEM, 2017, 2019). Studying the interaction between biological and social factors is therefore critically important to improve diagnosis, optimize treatments, increase access to care, improve care quality, reduce disability, and improve well-being.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

As summarized in this chapter and detailed throughout the report, the committee identified significant research gaps for women’s health and WHR across a number of domains, including a lack of understanding of basic female physiology (Chapter 5), insufficient study of certain conditions (Chapter 7), and inattention to the social determinants of women’s health outcomes (Chapter 6), including social and environmental factors that result in health inequities, and the need for research on the interaction of these factors. These gaps provide an opportunity for a concerted and coordinated effort to include more women in clinical trials, increase funding for WHR, and focus on both biological and social determinants of health. With the commitment of essential resources, infrastructure, and accountability, WHR will improve the quality of life of women and their families, benefit the economy, and promote a strong and healthy society.

REFERENCES

AAMC (Association of American Medical Colleges). 2024. The complexities of physician supply and demand: Projections from 2021 to 2036. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges.

Adler, R. A. 2000. Osteoporosis in men. In Endotext, edited by K. R. Feingold, B. Anawalt, M. R. Blackman, A. Boyce, G. Chrousos, E. Corpas, W. W. de Herder, K. Dhatariya, K. Dungan, J. Hofland, S. Kalra, G. Kaltsas, N. Kapoor, C. Koch, P. Kopp, M. Korbonits, C. S. Kovacs, W. Kuohung, B. Laferrère, M. Levy, E. A. McGee, R. McLachlan, M. New, J. Purnell, R. Sahay, A. S. Shah, F. Singer, M. A. Sperling, C. A. Stratakis, D. L. Trence, and D. P. Wilson. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc.

Badreldin, N., W. A. Grobman, and L. M. Yee. 2019. Racial disparities in postpartum pain management. Obstetrics and Gynecology 134(6):1147–1153.

Baird, M. D., M. A. Zaber, A. Chen, A. W. Dick, C. E. Bird, M. Waymouth, G. Gahlon, D. D. Quigley, H. Al-Ibrahim, and L. Frank. 2021. Research funding for women’s health: Modeling societal impact. Santa Monica, CA: WHAM and RAND Coorporation.

Bairey Merz, C. N., H. Andersen, E. Sprague, A. Burns, M. Keida, M. Norine Walsh, P. Greenberger, S. Campbell, I. Pollin, C. McCullough, N. Brown, M. Jenkins, R. Red-berg, P. Johnson, and B. Robinson. 2017. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding cardiovascular disease in women. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 70(2):123–132.

Bello, M. O., L. Rodrigues Silva Sombra, C. Anastasopoulou, and V. V. Garla. 2024. Osteoporosis in males. In Statpearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

Bloch, M., P. J. Schmidt, M. Danaceau, J. Murphy, L. Nieman, and D. R. Rubinow. 2000. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 157(6):924–930.

BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics). 2023. Labor Force Participation Rate for Women Highest in the District of Columbia in 2022. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2023/labor-force-participation-rate-for-women-highest-in-the-district-of-columbia-in-2022.htm (accessed August 12, 2024).

Bonafede, M., S. Sapra, N. Shah, S. Tepper, K. Cappell, and P. Desai. 2018a. Direct and indirect healthcare resource utilization and costs among migraine patients in the United States. Headache 58(5):700–714.

Bonafede, M. M., S. K. Pohlman, J. D. Miller, E. Thiel, K. A. Troeger, and C. E. Miller. 2018b. Women with newly diagnosed uterine fibroids: Treatment patterns and cost comparison for select treatment options. Population Health Management 21(S1):S13–s20.

Bovino, B. A., and J. Gold. 2018. The key to unlocking U.S. GDP growth: Women. Washington, DC: S&P Global.

Braveman, P., and L. Gottlieb. 2014. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports 129(Suppl 2):19–31.

Brown, M. 2020. Civic Engagement Benefits All of Us. So Why Are Women More Involved Than Men? https://www.forbes.com/sites/civicnation/2020/03/17/civic-engagement-benefits-all-of-us-so-why-are-women-more-involved-than-men/ (accessed October 3, 2024).

Bulun, S. 2016. Physiology and pathology of the female reproductive axis. In Williams Textbook of Endocrinology, 13th ed., edited by S. Melmed, K. S. Polonsky, P. R. Larsen, and H. M. Kronenberg. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences. Pp. 589–663.

Burch, R., P. Rizzoli, and E. Loder. 2021. The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States: Updated age, sex, and socioeconomic-specific estimates from government health surveys. Headache 61(1):60–68.

Casey, L. S., S. L. Reisner, M. G. Findling, R. J. Blendon, J. M. Benson, J. M. Sayde, and C. Miller. 2019. Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Services Research 54(S2):1454–1466.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2023. U.S. Teen Girls Experiencing Increased Sadness and Violence. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2023/p0213-yrbs.html (accessed September 4, 2024).

Census Bureau. n.d. Quickfacts: United States. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 (accessed August 8, 2024).

Chambers, B. D., B. Taylor, T. Nelson, J. Harrison, A. Bell, A. O’Leary, H. A. Arega, S. Hashemi, S. McKenzie-Sampson, K. A. Scott, T. Raine-Bennett, A. V. Jackson, M. Kuppermann, and M. R. McLemore. 2022. Clinicians’ perspectives on racism and Black women’s maternal health. Women’s Health Reports 3(1):476–482.

Chauhan, A., M. Walton, E. Manias, R. L. Walpola, H. Seale, M. Latanik, D. Leone, S. Mears, and R. Harrison. 2020. The safety of health care for ethnic minority patients: A systematic review. International Journal for Equity in Health 19(1):118.

Cheeseman Day, J., and C. Christnacht. 2019. Women Hold 76% of All Health Care Jobs, Gaining in Higher-Paying Occupations. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/08/your-health-care-in-womens-hands.html (accessed October 3, 2024).

Cho, L., A. M. Kaunitz, S. S. Faubion, S. N. Hayes, E. S. Lau, N. Pristera, N. Scott, J. L. Shifren, C. L. Shufelt, C. A. Stuenkel, and K. J. Lindley. 2023. Rethinking menopausal hormone therapy: For whom, what, when, and how long? Circulation 147(7):597–610.

Chumsri, S., T. Howes, T. Bao, G. Sabnis, and A. Brodie. 2011. Aromatase, aromatase inhibitors, and breast cancer. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 125(1–2):13–22.

Coffman, K. L., and P. Ash. 2019. Medicating during pregnancy. Focus 17(4):380–381.

Cortés, Y. I., and V. Marginean. 2022. Key factors in menopause health disparities and inequities: Beyond race and ethnicity. Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research 26:100389.

Courchesne, M., G. Manrique, L. Bernier, L. Moussa, J. Cresson, A. Gutzeit, J. M. Froehlich, D.-M. Koh, C. Chartrand-Lefebvre, and S. Matoori. 2024. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics: A perspective on contrast agents. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 7(1):8–17.

Cutler, A. S., L. S. Lundsberg, M. A. White, N. L. Stanwood, and A. M. Gariepy. 2021. Characterizing community-level abortion stigma in the United States. Contraception 104(3):305–313.

Dagher, R. K., H. E. Bruckheim, L. J. Colpe, E. Edwards, and D. B. White. 2021. Perinatal depression: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Women’s Health 30(2):154–159.

Delgado, B. J., and W. Lopez-Ojeda. 2023. Estrogen. In Statpearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

Deloitte. 2023. Hiding in plain sight: The health care gender toll. London: Deloitte.

Dennis, C.-L., and L. Chung-Lee. 2006. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: A qualitative systematic review. Birth 33(4):323–331.

Di Lego, V., P. Di Giulio, and M. Luy. 2020. Gender differences in healthy and unhealthy life expectancy. In International Handbook of Health Expectancies. Cham: Springer. Pp. 151–172.

Dou, D. R., Y. Zhao, J. A. Belk, Y. Zhao, K. M. Casey, D. C. Chen, R. Li, B. Yu, S. Srinivasan, B. T. Abe, K. Kraft, C. Hellström, R. Sjöberg, S. Chang, A. Feng, D. W. Goldman, A. A. Shah, M. Petri, L. S. Chung, D. F. Fiorentino, E. K. Lundberg, A. Wutz, P. J. Utz, and H. Y. Chang. 2024. Xist ribonucleoproteins promote female sex-biased autoimmunity. Cell 187(3):733–749.e716.

Drew, Y. 2015. The development of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: From bench to bedside. British Journal of Cancer 113(Suppl 1):S3–S9.

Eisenlohr-Moul, T. 2024. The Menstrual Cycle and Mental Health: Progress, Gaps, and Barriers. Presentation to the NASEM Committee on the Assessment of NIH Research on Women’s Health, Meeting 3 (March 7, 2024). https://www.nationalacademies.org/documents/embed/link/LF2255DA3DD1C41C0A42D3BEF0989ACAECE3053A6A9B/file/D200E053FE7DBEC81160D764F44F8C5682FD9C162A7A?noSaveAs=1 (accessed August 7, 2024).

El Khoudary, S. R., G. Greendale, S. L. Crawford, N. E. Avis, M. M. Brooks, R. C. Thurston, C. Karvonen-Gutierrez, L. E. Waetjen, and K. Matthews. 2019. The menopause transition and women’s health at midlife: A progress report from the study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause 26(10):1213–1227.

Eltoukhi, H. M., M. N. Modi, M. Weston, A. Y. Armstrong, and E. A. Stewart. 2014. The health disparities of uterine fibroid tumors for African American women: A public health issue. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 210(3):194–199.

Faubion, S. S., F. Enders, M. S. Hedges, R. Chaudhry, J. M. Kling, C. L. Shufelt, M. Saadedine, K. Mara, J. M. Griffin, and E. Kapoor. 2023. Impact of menopause symptoms on women in the workplace. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 98(6):833–845.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). 2018. Gender Studies in Product Development: Historical Overview. https://public4.pagefreezer.com/content/FDA/16-06-2022T13:39/https://www.fda.gov/science-research/womens-health-research/gender-studies-product-development-historical-overview (accessed August 8, 2024).

Friedman, A. M., C. V. Ananth, E. Prendergast, M. E. D’Alton, and J. D. Wright. 2015. Variation in and factors associated with use of episiotomy. JAMA 313(2):197–199.

Galea, L. A. M., E. Choleris, A. Y. K. Albert, M. M. McCarthy, and F. Sohrabji. 2020. The promises and pitfalls of sex difference research. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 56:100817.

Garcia, M., S. L. Mulvagh, C. N. Merz, J. E. Buring, and J. E. Manson. 2016. Cardiovascular disease in women: Clinical perspectives. Circulation Research 118(8):1273–1293.

Gioia, S. A., and J. G. Rosenberger. 2022. Sexual orientation-based discrimination in U.S. healthcare and associated health outcomes: A scoping review. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 19(4):1674–1689.

Glance, L. G., R. Wissler, C. Glantz, T. M. Osler, D. B. Mukamel, and A. W. Dick. 2007. Racial differences in the use of epidural analgesia for labor. Anesthesiology 106(1):19–25; discussion 16–18.

Gouin, J.-P., and J. K. Kiecolt-Glaser. 2011. The impact of psychological stress on wound healing: Methods and mechanisms. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America 31(1):81–93.

Greenblatt, D. J., J. S. Harmatz, and T. Roth. 2019. Zolpidem and gender: Are women really at risk? Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 39(3):189–199.

Guglielminotti, J., A. Lee, R. Landau, G. Samari, and G. Li. 2024. Structural racism and use of labor neuraxial analgesia among non-Hispanic Black birthing people. Obstetrics and Gynecology 143(4):571–581.

Hägg, S., and J. Jylhävä. 2021. Sex differences in biological aging with a focus on human studies. eLife 10:e63425.

Harlow, S. D., M. Gass, J. E. Hall, R. Lobo, P. Maki, R. W. Rebar, S. Sherman, P. M. Sluss, and T. J. de Villiers. 2012. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging workshop + 10: Addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause 19(4):387–395.

Harlow, S. D., S.-A. M. Burnett-Bowie, G. A. Greendale, N. E. Avis, A. N. Reeves, T. R. Richards, and T. T. Lewis. 2022. Disparities in reproductive aging and midlife health between Black and White women: The study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Women’s Midlife Health 8(1):3.

Hillner, B. E., J. N. Ingle, R. T. Chlebowski, J. Gralow, G. C. Yee, N. A. Janjan, J. A. Cauley, B. A. Blumenstein, K. S. Albain, A. Lipton, and S. Brown. 2003. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2003 update on the role of bisphosphonates and bone health issues in women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 21(21):4042–4057.

Howard, S. R. 2021. Interpretation of reproductive hormones before, during and after the pubertal transition—identifying health and disordered puberty. Clinical Endocrinology 95(5):702–715.

Hu, X. H., L. E. Markson, R. B. Lipton, W. F. Stewart, and M. L. Berger. 1999. Burden of migraine in the United States: Disability and economic costs. Archives of Internal Medicine 159(8):813–818.

Huang, Y., Y. Shan, W. Zhang, A. M. Lee, F. Li, B. E. Stranger, and R. S. Huang. 2023. Deciphering genetic causes for sex differences in human health through drug metabolism and transporter genes. Nature Communications 14(1):175.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1994. Women and health research: Ethical and legal issues of including women in clinical studies: Volume 2: Workshop and commissioned papers. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2010. Women’s health research: Progress, pitfalls, and promise. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Isiadinso, I., P. K. Mehta, S. Jaskwhich, and G. P. Lundberg. 2022. It takes a village: Expanding women’s cardiovascular care to include the community as well as cardiovascular and primary care teams. Current Cardiology Reports 24(7):785–792.

Jiang, J., J. Cui, A. Wang, Y. Mu, Y. Yan, F. Liu, Y. Pan, D. Li, W. Li, G. Liu, H. Y. Gaisano, J. Dou, and Y. He. 2019. Association between age at natural menopause and risk of Type 2 diabetes in postmenopausal women with and without obesity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 104(7):3039–3048.

Johnson, J. D., I. V. Asiodu, C. P. McKenzie, C. Tucker, K. P. Tully, K. Bryant, S. Verbiest, and A. M. Stuebe. 2019. Racial and ethnic inequities in postpartum pain evaluation and management. Obstetrics & Gynecology 134(6):1155–1162.

Karlamangla, A. S., A. Shieh, and G. A. Greendale. 2021. Hormones and bone loss across the menopause transition. Vitamins and Hormones 115:401–417.

Keteepe-Arachi, T., and S. Sharma. 2017. Cardiovascular disease in women: Understanding symptoms and risk factors. European Cardiology Review 12(1):10–13.

Kling, J. M., B. L. Clarke, and N. P. Sandhu. 2014. Osteoporosis prevention, screening, and treatment: A review. Journal of Women’s Health 23(7):563–572.

Kohl, J., A. E. Autry, and C. Dulac. 2017. The neurobiology of parenting: A neural circuit perspective. BioEssays 39(1):e201600159.

Lange, E. M. S., S. Rao, and P. Toledo. 2017. Racial and ethnic disparities in obstetric anesthesia. Seminars in Perinatology 41(5):293–298.

Lee, B., Y. Wang, S. A. Carlson, K. J. Greenlund, H. Lu, Y. Liu, J. B. Croft, P. I. Eke, M. Town, and C. W. Thomas. 2023. National, state-level, and county-level prevalence estimates of adults aged ≥18 years self-reporting a lifetime diagnosis of depression—United States, 2020. MMWR 72(24):644–650.

Lemaître, J.-F., V. Ronget, M. Tidière, D. Allainé, V. Berger, A. Cohas, F. Colchero, D. A. Conde, M. Garratt, A. Liker, G. A. B. Marais, A. Scheuerlein, T. Székely, and J.-M. Gaillard. 2020. Sex differences in adult lifespan and aging rates of mortality across wild mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(15):8546–8553.

Liese, K. L., M. Mogos, S. Abboud, K. Decocker, A. R. Koch, and S. E. Geller. 2019. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity in the United States. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 6(4):790–798.

Liu, K. A., and N. A. Mager. 2016. Women’s involvement in clinical trials: Historical perspective and future implications. Pharmacy Practice 14(1):708.

Long, M., B. Frederiksen, U. Ranji, A. Salganicoff, and K. Diep. 2022. Experiences with Health Care Access, Cost, and Coverage: Findings from the 2022 KFF Women’s Health Survey. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/experiences-with-health-care-access-cost-and-coverage-findings-from-the-2022-kff-womens-health-survey/ (accessed August 20, 2024).

Long, M., B. Frederiksen, U. Ranji, K. Diep, and A. Salganicoff. 2023. Women’s Experiences with Provider Communication and Interactions in Health Care Settings: Findings from the 2022 KFF Women’s Health Survey. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/womens-experiences-with-provider-communication-interactions-health-care-settings-findings-from-2022-kff-womens-health-survey/ (accessed August 20, 2024).

Lopes, L., A. Montero, M. Presiado, and L. Hamel. 2024. Americans’ Challenges with Health Care Costs. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/americans-challenges-with-health-care-costs/ (accessed August 8, 2024).

Lu, Z., J. K. Guo, Y. Wei, D. R. Dou, B. Zarnegar, Q. Ma, R. Li, Y. Zhao, F. Liu, H. Choudhry, P. A. Khavari, and H. Y. Chang. 2020. Structural modularity of the Xist ribonucleoprotein complex. Nature Communications 11(1):6163.

Magnan, S. 2021. Social determinants of health 201 for health care: Plan, do, study, act. NAM Perspectives 2021.

Marsh, E. E., G. Wegienka, and D. R. Williams. 2024. Uterine fibroids. JAMA 331(17):1492–1493.

Mauvais-Jarvis, F., D. J. Clegg, and A. L. Hevener. 2013. The role of estrogens in control of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Endocrine Reviews 34(3):309–338.

McPhee, C., I. O. Aninye, and L. Horan. 2022. Recommendations for improving women’s bone health throughout the lifespan. Journal of Women’s Health 31(12):1671–1676.

MD Anderson Cancer Center. 2023. ESMO: PARP Inhibitor Plus Immunotherapy Lowers Risk of Endometrial Cancer Progression Over Chemotherapy Alone. https://www.mdanderson.org/newsroom/esmo-parp-inhibitor-plus-immunotherapy-lowers-risk-of-endometrial-cancer-progression-over-chemotherapy-alone.h00-159622590.html (accessed October 21, 2024).

Mishra, S., H.-F. Chung, M. Waller, and G. Mishra. 2021. Duration of estrogen exposure during reproductive years, age at menarche and age at menopause, and risk of cardiovascular disease events, all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 128(5):809–821.

Montalmant, K. E., and A. K. Ettinger. 2024. The racial disparities in maternal mortality and impact of structural racism and implicit racial bias on pregnant Black women: A review of the literature. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 11(6):3658–3677.

Muehlenbein, M. P., J. Gassen, E. C. Shattuck, and C. S. Sparks. 2022. Lower testosterone levels are associated with higher risk of death in men. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health 11(1):30–41.

NAMS 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. 2022. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 29(7):767–794.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2019. Vibrant and healthy kids: Aligning science, practice, and policy to advance health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2022. Improving representation in clinical trials and research: Building research equity for women and underrepresented groups. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2023a. Federal policy to advance racial, ethnic, and tribal health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2023b. Inclusion of pregnant and lactating persons in clinical trials: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2024a. Advancing research on chronic conditions in women. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2024b. Ending unequal treatment: Strategies to achieve equitable health care and optimal health for all. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. 1979. The Belmont Report. Washington, DC: Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Nichols, T. R., A. Welborn, M. R. Gringle, and A. Lee. 2021. Social stigma and perinatal substance use services: Recognizing the power of the good mother ideal. Contemporary Drug Problems 48(1):19–37.

OASH (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health). 2023. Menopause Symptoms and Relief. https://www.womenshealth.gov/menopause/menopause-symptoms-and-relief (accessed September 13, 2024).

Okoro, O. N., L. A. Hillman, and A. Cernasev. 2020. “We get double slammed!”: Healthcare experiences of perceived discrimination among low-income African-American women. Women’s Health 16:1745506520953348.

Opoku, A. A., M. Abushama, and J. C. Konje. 2023. Obesity and menopause. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 88:102348.

ORWH (Office of Research on Women’s Health). n.d.-a. Clinical Research and Trials. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/womens-health-equity-inclusion/clinical-research-and-trials (accessed August 21, 2024).

ORWH. n.d.-b. NIH Inclusion Outreach Toolkit: How to Engage, Recruit, and Retain Women in Clinical Research: History of Women’s Participation in Clinical Research. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/toolkit/recruitment/history (accessed August 8, 2024).

ORWH. 2021. Historical Timeline—30 Years of Advancing Women’s Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health.

Öztürk, R., T. L. Bloom, Y. Li, and L. F. C. Bullock. 2021. Stress, stigma, violence experiences and social support of U.S. infertile women. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 39(2):205–217.

Payne, J. L., and J. Maguire. 2019. Pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in postpartum depression. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 52:165–180.

Plevkova, J., M. Brozmanova, J. Harsanyiova, M. Sterusky, J. Honetschlager, and T. Buday. 2020. Various aspects of sex and gender bias in biomedical research. Physiological Research 69(Suppl 3):S367–S378.

Prather, C., T. R. Fuller, K. J. Marshall, and W. L. Jeffries. 2016. The impact of racism on the sexual and reproductive health of African American women. Journal of Women’s Health 25(7):664–671.

Puhl, R. M., T. Andreyeva, and K. D. Brownell. 2008. Perceptions of weight discrimination: Prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. International Journal of Obesity 32(6):992–1000.

Raman, S., and A. Cohen. 2023. Ob-Gyn Workforce Shortages Could Worsen Maternal Health Crisis. https://burgess.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=403659 (accessed August 8, 2024).

Robson, M., S. A. Im, E. Senkus, B. Xu, S. M. Domchek, N. Masuda, S. Delaloge, W. Li, N. Tung, A. Armstrong, W. Wu, C. Goessl, S. Runswick, and P. Conte. 2017. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. New England Journal of Medicine 377(6):523–533.

Salsberg, E., C. Richwine, S. Westergaard, M. Portela Martinez, T. Oyeyemi, A. Vichare, and C. P. Chen. 2021. Estimation and comparison of current and future racial/ethnic representation in the U.S. health care workforce. JAMA Network Open 4(3):e213789.

Saylor, P. J., R. B. Rumble, and J. M. Michalski. 2020. Bone health and bone-targeted therapies for prostate cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology endorsement summary of a Cancer Care Ontario guideline. JCO Oncology Practice 16(7):389–393.

Sayres Van Niel, M., and J. L. Payne. 2020. Perinatal depression: A review. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 87(5):273–277.

Schmidt, P. J., L. Nieman, M. A. Danaceau, M. B. Tobin, C. A. Roca, J. H. Murphy, and D. R. Rubinow. 2000. Estrogen replacement in perimenopause-related depression: A preliminary report. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 183(2):414–420.

Schofield, C. A., S. Brown, I. E. Siegel, and C. A. Moss-Racusin. 2024. What you don’t expect when you’re expecting: Demonstrating stigma against women with postpartum psychological disorders. Stigma and Health 9(3).

Schreier, H. M. C., M. Bosquet Enlow, T. Ritz, B. A. Coull, C. Gennings, R. O. Wright, and R. J. Wright. 2016. Lifetime exposure to traumatic and other stressful life events and hair cortisol in a multi-racial/ethnic sample of pregnant women. Stress 19(1):45–52.

Shamsi, H. A., A. G. Almutairi, S. A. Mashrafi, and T. A. Kalbani. 2020. Implications of language barriers for healthcare: A systematic review. Oman Medical Journal 35.

Soares, C. N., and B. Zitek. 2008. Reproductive hormone sensitivity and risk for depression across the female life cycle: A continuum of vulnerability? Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 33(4):331–343.

Soldin, O. P., and D. R. Mattison. 2009. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 48(3):143–157.

Sosinsky, A. Z., J. W. Rich-Edwards, A. Wiley, K. Wright, P. A. Spagnolo, and H. Joffe. 2022. Enrollment of female participants in United States drug and device Phase 1–3 clinical trials between 2016 and 2019. Contemporary Clinical Trials 115:106718.

Srikanth, N., L. Xie, J. Francis, and S. E. Messiah. 2023. Association of social determinants of health, race and ethnicity, and age of menarche among U.S. women over 2 decades. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 36(5):442–448.

Stall, N. M., N. R. Shah, and D. Bhushan. 2023. Unpaid family caregiving—the next frontier of gender equity in a postpandemic future. JAMA Health Forum 4(6):e231310.

Steele, L. S., A. Daley, D. Curling, M. F. Gibson, D. C. Green, C. C. Williams, and L. E. Ross. 2017. LGBT identity, untreated depression, and unmet need for mental health services by sexual minority women and trans-identified people. Journal of Women’s Health 26(2):116–127.

Still, C. H., S. Tahir, H. N. Yarandi, M. Hassan, and F. A. Gary. 2020. Association of psychosocial symptoms, blood pressure, and menopausal status in African-American women. Western Journal of Nursing Research 42(10):784–794.

Superville, D. R. 2023. Women in the K–12 Workforce, by the Numbers. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/women-in-the-k-12-workforce-by-the-numbers/2023/03 (accessed October 3, 2024).

Taylor, A. M., D. L. H. Chan, M. Tio, S. M. Patil, T. A. Traina, M. E. Robson, and M. Khasraw. 2021. PARP (poly ADP-ribose polymerase) inhibitors for locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4(4):Cd011395.

Temkin, S. M., S. Noursi, J. G. Regensteiner, P. Stratton, and J. A. Clayton. 2022. Perspectives from advancing National Institutes of Health research to inform and improve the health of women: A conference summary. Obstetrics and Gynecology 140(1):10–19.

Temkin, S. M., E. Barr, H. Moore, J. P. Caviston, J. G. Regensteiner, and J. A. Clayton. 2023. Chronic conditions in women: The development of a National Institutes of Health framework. BMC Women’s Health 23(1):162.

Thase, M. E., R. Entsuah, M. Cantillon, and S. G. Kornstein. 2005. Relative antidepressant efficacy of venlafaxine and SSRIs: Sex-age interactions. Journal of Women’s Health 14(7):609–616.

Trost, S., J. Beauregard, G. Chandra, F. Njie, J. Berry, A. Harvey, and D. A. Goodman. 2022. Pregnancy-related deaths: Data from maternal mortality review committees in 36 U.S. states, 2017–2019. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Valentine, J. A., L. F. Delgado, L. T. Haderxhanaj, and M. Hogben. 2022. Improving sexual health in U.S. rural communities: Reducing the impact of stigma. AIDS and Behavior 26(1):90–99.

van Oosterhout, R. E. M., A. R. de Boer, A. H. E. M. Maas, F. H. Rutten, M. L. Bots, and S. A. E. Peters. 2020. Sex differences in symptom presentation in acute coronary syndromes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association 9(9):e014733.

Vohra-Gupta, S., L. Petruzzi, C. Jones, and C. Cubbin. 2023. An intersectional approach to understanding barriers to healthcare for women. Journal of Community Health 48(1):89–98.

Wang, S. S. Y., Y. E. Jie, S. W. Cheng, G. L. Ling, and H. V. Y. Ming. 2023. PARP inhibitors in breast and ovarian cancer. Cancers 15(8).

Weinberger, A. H., S. A. McKee, and C. M. Mazure. 2010. Inclusion of women and gender-specific analyses in randomized clinical trials of treatments for depression. Journal of Women’s Health 19(9):1727–1732.

Whitman, A., N. De Lew, A. Chappel, V. Aysola, R. Zuckerman, and B. D. Sommers. 2022. Addressing social determinants of health: Examples of successful evidence-based strategies and current federal efforts. Washington, DC: Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

WHO (World Health Organization). n.d. Social Determinants of Health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed October 21, 2024).

Williamson, L. 2024. Families Often Have Chief Medical Officers—and They’re Almost Always Women. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2024/04/17/families-often-have-chief-medical-officers-and-theyre-almost-always-women (accessed October 3, 2024).

Yan, B. W., E. Arias, A. C. Geller, D. R. Miller, K. D. Kochanek, and H. K. Koh. 2024. Widening gender gap in life expectancy in the U.S., 2010–2021. JAMA Internal Medicine 184(1):108–110.

Yermachenko, A., and V. Dvornyk. 2014. Nongenetic determinants of age at menarche: A systematic review. BioMed Research International 2014(1):371583.

Zhao, H., M. DiMarco, K. Ichikawa, M. Boulicault, M. Perret, K. Jillson, A. Fair, K. DeJesus, and S. S. Richardson. 2023. Making a “sex-difference fact”: Ambien dosing at the interface of policy, regulation, women’s health, and biology. Social Studies of Science 53(4):475–494.

This page intentionally left blank.