A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health (2025)

Chapter: 4 Overview of the National Institutes of Health Investment in Women's Health Research

4

Overview of the National Institutes of Health Investment in Women’s Health Research

INTRODUCTION

This chapter describes how the National Institutes of Health (NIH) tracks funding and undertakes portfolio analysis; it then presents the committee’s assessment of NIH funding for women’s health research (WHR). Because women’s health includes diseases and conditions that are sex specific or affect women and men differently or disproportionally, the task of measuring the state of NIH funding for research on the health of women, the nature of the gaps, and establishing a standard for allocation each present challenges.

The easiest of these challenges may be assessing the funding for female-specific diseases and conditions. However, the domain also includes studying female development, including the effect of sex hormones over the life course, which have also been understudied and lack an institutional home within NIH (see Chapter 5). Adding to the complexity are decisions regarding how to account for research on pregnancy, which often focuses primarily or exclusively on fetal or infant outcomes rather than the health of the pregnant person. Such work may be of interest and importance to women, and presumably men, without being directly tied to their health.

Gaps in sex-specific research on women’s health include areas discussed in prior chapters, such as in the funding of research on endometriosis and reproductive cancers specific to women. This also raises the issue of how to count research on diseases and conditions experienced predominantly but not exclusively by women, such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis; the disease burden and research have focused largely on female patients, but the

evidence base and funding fall far below that of diseases experienced by male patients, either predominantly or exclusively (Mirin, 2021; Salari et al., 2021).

The more challenging category to assess is diseases that affect women and girls differently from men and boys. This depends on not just the funding that went to research on such diseases but also the extent to which that research examined whether there are sex or gender differences and the underlying mechanisms or drivers of those differences. Moreover, there is an additional question of what proportion of the study’s funding should be categorized as examining women’s health. At one extreme, that could include all the funding on a study that reported whether and how findings differed for women compared to men and the implications for treatment and future research. At the other extreme, it might only include the marginal costs of the additional analyses required. That proportion also might be seen as a function of both their representation in the research and the analyses proposed or conducted that contribute to evidence-based care for them. With perfect information, such a gold standard would be informative.

This chapter focuses on the proportion of NIH funding going to research on women’s health, not on what the gold standard could be. That would ideally reflect objective measures, including the relative and absolute burden of diseases and conditions. However, since the gaps in the evidence base also include a lack of research on the range of female development, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to hold all assessments to that standard. In addition, individual rare diseases, also known as “orphan diseases,”1 have a small effect relative to those experienced by a larger share of the population. The study of them not only is humane and needed but also can create opportunities for breakthrough science, as they almost by definition fall outside the existing evidence base and are often undercounted as a result.

A question frequently arises as to what portion of the NIH budget funds research on the health of men. Until the 1993 NIH Revitalization Act,2 that answer was simpler, as the vast majority of funding was for not only sex-specific diseases and conditions but also those that affect men and women. Unfortunately, including women as research participants and female animals and tissues in studies has had a limited effect on informing women’s health by having been built primarily on theories and evidence from a focus on men. For example, work ranging from heart disease to autism has been limited in part by diagnostic tools, criteria, and interventions based on studying male participants as normal and including female participants who either fit that model or were labeled “atypical presentation.” These limitations have been confounded by a lack of work

___________________

1 According to the Orphan Drug Act, orphan diseases or conditions are defined as those affecting fewer than 200,000 in the United States (Public Law 97–414). [This footnote was changed after release of the report to clarify the source of the definition.]

2 Public Law 103–143, 107 Stat. 122 (June 10, 1993).

systematically assessing whether and to what extent findings from studies conducted in mixed-sex samples hold for female patients. Assessing the extent to which studies propose to and do carry out such analyses is unfortunately beyond the resources and time frame of this report. However, the goal of clearly establishing to whom findings of a given study applies warrants considerable attention as part of the effort to build an evidence base on the health of women (IOM, 2001; Liu and Mager, 2016).

What is the ideal or optimal balance between spending on sex-specific diseases and conditions depends in large part on how much a given sex experiences and is burdened by them. For example, to the extent that women experience more diseases and disease burden from cancer in or related to reproductive organs or hormones, a higher allocation to funding of research on diseases specific to them is warranted. The size of the existing evidence base is also relevant; the issue is how well the sex-specific diseases and conditions have been studied and are understood. The gap is a function of the disease burden and the extent of the evidence base to date.

The long-standing emphasis of NIH funding on diseases and conditions affecting men has reinforced the idea that male bodies are the standard and treated female bodies as an exception. For example, most urologic conditions in men fall under the general practice of urology, whereas many in women are addressed almost exclusively in the subspecialty of urogynecology. Thus, the relative need for research specific to females versus males is in part a function of the long-standing and erroneous assumption that the latter could routinely be generalized to women’s health and health care.

ASSESSING DISEASE AND CONDITION FUNDING LEVELS AT NIH

The committee faced a fundamental challenge in evaluating NIH investment in WHR. It sought to examine current spending and the trajectory of spending on WHR over the past 10 years. On the surface, this should be a straightforward exercise. NIH expenditures are matter of public record, and the agency has a strong commitment to transparency. However, NIH uses multiple systems to account for its research expenditures, and the data needed for such an evaluation can be difficult to interpret. Some of the evaluation systems, such as the Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT) website and associated RePORT Expenditures and Results (RePORTER) tool, are public facing, meaning anyone can access them. Other tools, such as the Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) system and Search and Visualize intersect tool, are for internal use and people outside the government cannot access them. These tools can help NIH Institutes and Centers (ICs) analyze their portfolios in more depth and recognize trends and gaps in their research funding (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; ORWH, 2023).

Reporting Categorical Funding: Process and Challenges

Tracking NIH research expenditures is a monumental task. Each year, more than 58,000 NIH grants support more than 300,000 investigators at more than 2,700 different institutions (Lauer, 2024; NIH, 2023a). Since fiscal year (FY) 2008, the primary system used to account for NIH categorical expenditures is RCDC (NIH, n.d.-a). Congress mandated creating it in the NIH Reform Act of 20063 to uniformly categorize NIH-funded research projects at all ICs and better understand how research dollars are used (NASEM, 2024a; NIH, 2024a). The Division of Scientific Categorization and Analysis (DSCA) within the Office of Extramural Research in the NIH Office of the Director (OD) maintains and curates RCDC categories with the assistance of IC subject matter experts. Data and scientific information analysts and computational linguists staff DSCA (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024).

NIH is required to use RCDC to publicly report how much is spent for research through grants and other funding mechanisms annually in NIH-wide defined categories. The number of RCDC categories has increased over time, and each year, new ones are introduced (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024). For FY 2023 reporting, there were 324 public categories;4 NIH also uses nonpublic categories internally (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024). Requests from Congress, the White House, NIH leadership, and advocacy groups, as well as evolving research (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; NIH, n.d.-c,d), drive the development of new RCDC categories. An internal NIH working group decides if a newly proposed category should be added, with approvals prioritized by research urgency and the number of requests (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024). For example, because of the obvious omission, Congress requested a category for menopause, which was reported via RCDC in 2024 (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; NIH, 2024b). Subject matter experts from across NIH define the scientific parameters for RCDC categories and also validate individual projects to ensure category accuracy (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024). The RePORT website offers public access to a downloadable spreadsheet that summarizes NIH expenditures for each category; many advocacy groups have used these data to educate their constituents, lobby for additional funding, and highlight inequities in NIH funding (Baird et al., 2021; NASEM, 2024a,b; NIH, 2024a). New RCDC categories are not retroactively applied to past fiscal years, but NIH internally examines past research trends (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; NASEM, 2024a; NIH, n.d.-b). This limits public understanding of the trajectory of NIH funding. For example, the category for cervical cancer

___________________

3 Public Law 109–482, 120 Stat. 3675 (January 15, 2007).

4 See https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/ for a listing of all RCDC categories (accessed July 25, 2024).

was created in 2008, vaginal cancer in 2015, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in 2022 (NIH, 2024a). Research on these women’s health topics was occurring before their RCDC categories were established, limiting the accuracy of funding totals for diseases by NIH over time.

The RCDC system’s fundamental methodology has not changed, though improvements in natural language processing have been integrated to increase specificity and accuracy (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024). A category is made up of a list of weighted biomedical concepts, known as a “category fingerprint,” sourced from the RCDC Thesaurus that are relevant to it and may have many synonyms. For example, the ALS category comprises concepts such as “ALS pathology,” “ALS patients,” and “amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; NIH, n.d.-c). The Thesaurus is foundational to the RCDC system and amended as science and language advance.

To index a project, the automated system mines the title, abstract, public health relevance, and specific aims sections of each project application using natural language processing techniques. Thesaurus concepts in project text are compared to category fingerprints, and if enough overlap5 appears between these and the text, the project is reported in that category (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; NIH, n.d.-b,c). Nearly all RCDC categories are reported in this automated way, and dollars are reported at the full project amount for each category in which the project is listed (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; NIH, n.d.-b). According to NIH, the Women’s Health RCDC category is reported manually6—subject matter experts determine if projects need to be reported in a category. Dollars can be prorated (1–100 percent) based on the portion of the project that meets the category definition (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; Lauer, 2018; NIH, n.d.-b).

As the official source of categorical reporting for NIH-funded research projects, the system is consistent in its budgetary allocation methodology and offers standardized project-level reporting (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024). However, interpreting RCDC data has some important caveats. While new research areas continue to be added based on official requests, the RCDC categories do not encompass all types of biomedical research or all health conditions (Lauer, 2018). RCDC categories are not a sum of the total NIH expenditure, and NIH does not budget by RCDC categories (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; NIH, n.d.-a).

___________________

5 NIH has an empirical threshold value for each RCDC category that it has determined minimizes false positives and false negatives; “enough overlap” means a project has crossed that threshold (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; NIH, n.d.-b).

6 Email communication with Nancy Praskievicz, Division of Scientific Categorization and Analysis, National Institutes of Health on October 7, 2024.

In addition, categories overlap and are not mutually exclusive, so individual projects may be reported in multiple categories (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; NIH, n.d.-a). For example, a grant for a clinical trial to treat cachexia in breast cancer might meet the threshold for five different categories: Clinical Trials and Supportive Activities, Cachexia, Breast Cancer, Cancer, and Women’s Health (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024). As described, the entire budget of the grant is attributed to each RCDC category that it falls into, or, for manually reported categories, prorated to account for the percentage of the project meeting the category definition. The automated system cannot parse project funding by category, such as deciding that 50 percent went to one category, 30 percent to a second, and 20 percent to a third. According to NIH, this would require a burdensome manual process that could introduce data discrepancies (Cebotari and Praskievicz, 2024; Lauer, 2018; NASEM, 2024a). As a result, the overall total research spending reported via the RCDC system will be higher than the NIH budget (Lauer, 2018). Since the grants cannot be prorated across multiple categories, this approach results in an overestimate in spending for many categories, given that the full amount of a grant is included even if it focuses on more than one disease or condition. As a result, if members of the public were to use RCDC categories to sum the funding allocated for various women’s health–related categories, such as all female-specific cancers, this would overestimate the total funding because many grants study more than one female-specific cancer, so they would be counted across multiple categories.

NIH Reporting of Funding for WHR

Of particular interest to the committee is the RCDC category and reporting algorithm for Women’s Health.7 The specific definition used by RCDC to categorize Women’s Health grants is not publicly available, though it includes conditions that exclusively affect women, while other conditions that affect women either predominantly or differently are reviewed

___________________

7 NIH notes, “Reporting for this category now more closely follows the standard RCDC process compared with the project identification, cost pro-ration, and validation procedures used for FY 2018 and prior fiscal years. Individual Institutes, Centers, and Offices (ICOs) previously classified reportable awards using subjectively-defined criteria and assigned funding based on percentages of female subjects included in the studies. In FY 2019, subject matter experts across ICOs achieved consensus that the allocation of women’s health-related spending should be grounded on scientific relevance and developed new prorating guidance, accordingly. To ensure a robust reporting transition, starting FY 2019, ICOs applied the new definitions only to the competing projects and retained the previous prorating schemes for the non-competing awards and will gradually roll-out from the inclusion-based approach in the subsequent fiscal years. In conjunction with the described efforts, NIH also instituted the use of an automated Manual Categorization System (MCS) to enhance workflow efficiency and standardize the NIH-wide cost allocation practices” (NIH, 2024a).

by IC subject matter experts for relevance to Women’s Health; because it is a manual effort, approaches are unique to each IC, and reporting is at each IC’s discretion.8 As of 2023, NIH IC experts can include projects that (1) recruit female participants and (2) focus on female-specific diseases or conditions, such as breast or cervical cancers, endometriosis, PCOS, and maternal health.

NIH IC experts, at their discretion, can also include conditions that predominately affect women.9 Projects centering on child health outcomes are not included unless they focus mainly on girls. Funding for studies that involve both women and men or partially address women’s health can be manually prorated (1–100 percent of the obligated dollar amount) based on, for example, disease burden or the proportion of study aims related to women’s health, depending on each IC’s approach to coding and proration.10 Basic science studies can be prorated by the proportion of women’s health-related study aims or percentage of female research subjects; if that information is unknown, funding can be reported at 50 percent. DSCA has also confirmed that the category includes topics that do not have their own categories. For example, projects on menstruation could appear in the Women’s Health RCDC category even though no menstruation category exists.11 The Women’s Health category also includes relevant grants for women’s health career development and conferences. The RePORT website includes individual projects listed in the Women’s Health RCDC category since FY 2020 (NIH, 2024a).

However, based on its review of abstracts from RePORTER when preparing for its funding analysis (see Appendix A), the committee identified a large number of grants coded as Women’s Health that did not appear to be related, in that the grant did not focus on a female-specific condition or a condition more common in women and was not assessing sex differences for a condition present in both sexes. The committee did not have access to the full grant and so could only base this assessment on the title, abstract, and public health relevance statement. However, the committee found a smaller proportion of grants on WHR than what is reported in the Women’s Health category (see funding analysis), further indicating that some of the grants in that category could be miscategorized, leading to an overestimate of funding for WHR.

___________________

8 Email communication with Nancy Praskievicz, Division of Scientific Categorization and Analysis, National Institutes of Health on October 7, 2024.

9 Email communication with Nancy Praskievicz, Division of Scientific Categorization and Analysis, National Institutes of Health on October 7, 2024.

10 Email communication with Nancy Praskievicz, Division of Scientific Categorization and Analysis, National Institutes of Health on October 7, 2024.

11 Email communication with Nancy Praskievicz, Division of Scientific Categorization and Analysis, National Institutes of Health on January 26, 2024.

Based on current RCDC methods, NIH is estimated to spend $4.6 billion on Women’s Health in FY 2024 (approximately 10 percent of the NIH Congressional appropriation) and $5 billion in FY 2025 (NIH, 2024a). Recent evaluations by NIH of its spending for Women’s Health are documented in the biennial Report of the Advisory Committee on Research on Women’s Health: Fiscal Years 2021–2022 (ORWH, 2023). It defined women’s health using language from Section 141 of the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993,12 which also established the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH). Specifically, the advisory committee defined women’s health as “all diseases, disorders, and conditions: (1) that are unique to, more serious in, or more prevalent in women, (2) for which the factors of medical risk or types of medical intervention are different for women or for which it is unknown whether such factors or types are different for women, and (3) with respect to which there has been insufficient clinical research involving women as subjects or insufficient clinical data on women.” This definition also includes research on prevention of such conditions (ORWH, 2023).

ORWH summarized funding data for three broad areas in the report: (1) female-specific diseases and conditions, (2) diseases and conditions that occur predominantly among women, and (3) other ORWH-selected diseases and conditions that have particularly important implications for women even though they may affect both men and women.

Before FY 2020, NIH (and all Department of Health and Human Services agencies) used the Moyer Women’s Health Crosscutting Category report (Moyer Report) to classify research funding by disease and condition categories annually using mandated specific categories and budget allocation definitions. Since then, the best available data come from the RCDC system and some of its internal tools. Among the 315 RCDC categories in FY 2022, about 40 were regarded as highly relevant to women’s health and analyzed in the biennial report from the advisory committee (ORWH, 2023). Unfortunately, the change in policy for reporting created a discontinuity, and categories used after FY 2022 may not be directly comparable to those used in prior years (ORWH, 2023).

ORWH reports NIH’s spending for WHR was $4.59 billion in FY 2022, a 2.8 percent increase from FY 2020 (ORWH, 2023). For many RCDC categories, exclusive focus on women—Fibroid Tumors (Uterine), Endometriosis, and Uterine Cancer, for example—can be identified clearly, so all expenditures are justifiably attributable to Women’s Health. For conditions that affect both women and men, however, it is necessary to estimate the proportion of expenditures that apply to Women’s Health. To make these estimates, ORWH used the internal Search and Visualize intersect tool (ORWH, 2023). As expected, variability in expenditure was wide across

___________________

12 Public Law 103–143, 107 Stat. 122 (June 10, 1993).

RCDC categories. Categories with the greatest total expenditure in FY 2022 include Breast Cancer; Maternal Health, including Maternal Morbidity and Mortality as a subcategory; Pregnancy; and Contraception/Reproduction. However, Aging, Autoimmune Disease, Cardiovascular, Diabetes, Mental Health, and Substance Misuse RCDC categories had the largest expenditures overall, in the billions of dollars. The proportion attributed to women’s health within these categories was estimated to be 16–28 percent of the total. Except for breast cancer, total investments for female-specific diseases tend to be more modest (ORWH, 2023).

ORWH also reports significant increases in expenditure from FY 2020 to FY 2022 for several conditions within each of the three broad categories analyzed. For example, among female-specific diseases and conditions, ORWH reported increases in the research budget for Cervical and Uterine Cancers (29.5 percent and 13.5 percent increases, respectively), Endometriosis (89.7 percent), and Maternal Health (37.2 percent) (ORWH, 2023). Cervical cancer and maternal health funding have benefited in part from efforts that focused more attention on these issues, including the Congressionally mandated 2021 ORWH conference on Advancing NIH Research on the Health of Women, which included static cervical cancer survival rates and maternal morbidity and mortality as two of three major priority areas (ORWH, n.d.), and NIH-wide Implementing a Maternal Health and Pregnancy Outcomes Vision for Everyone Initiative and its associated national network of Maternal Health Research Centers of Excellence launched in FY 2022 (NICHD, n.d.; NIH, 2023b). Ovarian Cancer, Fibroid Tumors (Uterine), and Vulvodynia were among the categories with decreased research expenditures from FY 2020 to FY 2022 (5.5, 15.1, and 37.9 percent decreases, respectively) (ORWH, 2023).

PORTFOLIO ANALYSIS

NIH established the Office of Portfolio Analysis (OPA) in 2011 within the Division of Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives under the OD, in response to the NIH Reform Act of 2006.13 OPA’s goal is “to accelerate biomedical research by providing access to improved methods of data-driven decision making” (OPA, 2021). This goal guides OPA’s objectives of improving data and tools to help NIH policy makers optimize decisions and investments and creating and distributing high-quality metrics and standards for portfolio analysis at NIH (OPA, 2021). OPA’s strategic plan emphasizes enhancing decision-making processes through refined analytics and tools, supporting NIH’s strategic goals. OPA supports NIH leadership and ICs and Offices (ICOs) through data cleaning and analysis

___________________

13 Public Law 109–482, 120 Stat. 3675 (January 15, 2007).

and developing new analytics and computational tools to answer critical questions about the NIH portfolio, including potential gaps (OPA, 2021). OPA also maps research topics and can measure productivity and effect of NIH-funded research. It disseminates best practices for portfolio analysis through trainings and symposiums. OPA collaborates across NIH, such as with the National Library of Medicine and Offices within the OD, such as the Offices of Extramural and Intramural Research and the Office of Science Policy. These actions help NIH in strategic planning and portfolio management and in assessing resource allocation to ensure a comprehensive distribution of biomedical research investment (OPA, 2021).

OPA uses a variety of internal- and external-facing methods and tools to evaluate current and emerging research areas and the progress of the scientific enterprise. For example, OPA uses artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms to create metrics to quantify research investment productivity and effect, characterize the scientific workforce, and predict breakthroughs in key research areas likely to yield significant advances within 2–12 years (NASEM, 2024a; OPA, 2021). Data sources for these metrics include grant applications and awards, publications, clinical trials, patents, and associated metadata, such as authorship, affiliations, and citations (OPA, 2021). Specific tools include iSearch, an internal, next-generation analysis suite, and iCite, a public dashboard of bibliometrics for published papers associated with a research portfolio, such as endometriosis or osteoporosis. Tools within iCite quantify scientific influence of published papers and predict the likelihood of citation by clinical trials and clinical guidelines (iCite, n.d.; OPA, 2021).

However, focusing on publications as a measure of effect, even via a sophisticated metric, does not necessarily capture whether research grants are leading to improved health outcomes (see Chapter 8 for a discussion of publication bias, which also affects the usefulness of this measure). It would be beneficial to track and publish information on the WHR workforce, including how many NIH-funded early-career investigators continue to publish, continue to be awarded NIH grants, remain in academia, or remain in science, for example (see Chapter 9 for a discussion of metrics).

OPA’s approach to analyzing topics such as NIH-funded WHR starts with the women’s health RCDC category and then extends beyond that using machine learning, input from subject matter experts, and artificial intelligence and language modeling to examine the whole NIH portfolio. OPA trains its artificial intelligence model on scientific data from the whole research landscape of 40 million publications and 4 million grant documents categorized based on computational model–based assessments and then checked by subject matter experts (NASEM, 2024a).

SUMMARY OF NIH ASSESSMENTS OF FUNDING FOR WHR

In summary, the approach used to assess funding for WHR at NIH has limitations. The major limitations include inaccurate grant content curation, lack of transparency, and the potential for overestimation of spending in RCDC categories. First, the system does not always accurately identify grants as related or unrelated to women’s health, and the full definition of women’s health NIH uses for research expenditures is not public, limiting transparency and reproducibility. This issue is intrinsic to research topics or areas that are broad or crosscutting, given that conventional search tools are unable to easily distinguish, for example, if a grant is actually focused on women’s health or mentions that women are in the study but is not focused on measuring outcomes directly or indirectly related to their health. When grants are manually categorized by NIH, it is not clear what process (i.e., for coding and proration of dollars) is used because it is implemented differently by each IC and not done systematically across NIH. Second, the publicly available data (i.e., NIH RePORTER) overestimate the total expenditure on WHR (and other research areas) because it allows for each relevant grant to be counted multiple times. Because of these limitations, in addition to other limitations discussed (e.g., some RCDC codes were only recently created, so cannot be used to assess trends over time, and many diseases and conditions do not have a code), the committee undertook a different approach, described in Appendix A and the following section.

The committee suggests implementing alternative accounting systems and methods to improve accuracy. First, more advanced systems and tools are needed to curate grant content to more accurately discern relevance to a given topic or area, such as women’s health. This may involve asking grantees to assist with classifying and categorizing their topic area and focus. It may also involve using more advanced tools, such as large language models, to curate grant content to more accurately identify any grant relevance and then discern the degree of relevance to a given topic area such as women’s health. An ideal solution might use both approaches.

Second, more systematic approaches are needed when reporting spending categories in RePORTER to avoid multiple counting of grants with potential relevance to a given topic. This could involve categorizing grants by main funding priorities for NIH first, such as women’s, children’s, or men’s health, and then subcategorizing by disease or condition. This could also involve applying a weighting system to assign proportions of the expenditure for each grant relevant to multiple spending categories in a consistent manner so that the full amount is not simultaneously assigned to multiple diseases and condition spending categories. For example, the full budget of a cancer center grant should not be counted multiple times for each of the many different types of cancers being studied, as this would not accurately

reflect the resources devoted to study each cancer. Ultimately, the sum of expenditures across categories would equal the actual research budget.

The committee heard from DSCA staff, in addition to leaders from OPA and the Office of Evaluation, Performance, and Reporting, at its second committee meeting (see Appendix C for public meeting agendas), and these groups acknowledged the limitations of the RCDC system.

THE COMMITTEE’S ANALYSIS OF NIH FUNDING FOR WHR

As noted in Chapter 1, the committee defines WHR as the scientific study of the range of and variability in women’s health and the mechanisms and outcomes in disease and non-disease states across the life course. It considers both sex and gender and how these affect women’s health and wellbeing, disease risk, pathophysiology, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. This work also addresses interacting concerns related to women’s bodies, roles, and social and structural determinants and systems14 (see Key Terms at the beginning of this report).

As described in Chapter 3, NIH funds several types of research, including basic science, preclinical, clinical, population-based, and implementation research, all of which have a role in broadening understanding of women’s health (e.g., exploring risk and protective factors; see Recommendation 8 for more examples). Funding for research on women’s health is provided through both extramural and intramural grants awarded by various ICOs at NIH, including the OD. Of the total 27 ICs, two do not provide funding, the Center for Scientific Review and NIH Clinical Center. The remaining 25, in addition to the OD, receive funding each FY for awarding grants across various domains of biomedical research. Using publicly available data from NIH RePORTER15 and the methodology in Appendix A,16 the committee conducted an analysis to determine trends over time in the allocation of NIH grants to fund WHR. It involved a comprehensive review of the abstract text extracted for all NIH grants funded during FY 2013–FY 2023. The grants related to WHR were identified from systematic abstract text curation coupled with human adjudication. Funding data on WHR was examined for

___________________

14 Adapted from Canada’s National Women’s Health Research Initiative.

15 RePORTER is an electronic database that “allows users to search a repository of NIH-funded projects and access publications and patents resulting from NIH funding” (NIH, n.d.-d). It draws data from several databases, including eRA databases, Medline, PubMed Central, the NIH Intramural Database, and iEdison. It is updated weekly to reflect both new projects and revisions to existing projects (such as if a grantee’s institution has changed or the award amount has changed) (NASEM, 2022; NIH, n.d.-d).

16 See Appendix A for a description of the methods for this analysis, limitations, and supplemental data tables and figures. Additional data tables are available in the project’s Public Access File and upon request from PARO@nas.edu.

NIH as a whole and each of the 25 funding ICs plus the OD, henceforth referred to as the “ICs” for the purposes of this analysis.

Overall Funding Trends

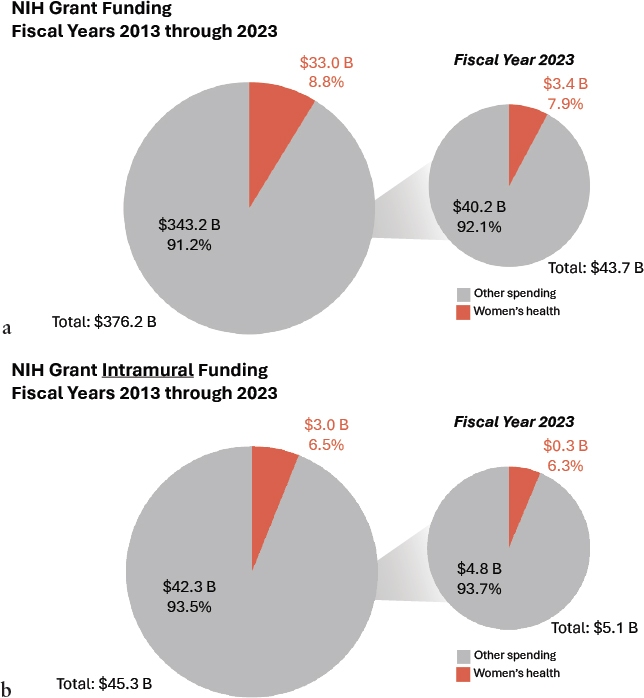

During FY 2013–FY 2023, the total grant funding for WHR amounted to 8.8 percent of all NIH spending on research grants awarded for these years, while NIH has reported 10 percent of its budget is spent on WHR17 (Clayton, 2023; ORWH, 2023). The proportion of total NIH grant funding for WHR was 7.9 percent in FY 2023 (see Figure 4-1). A low proportion

___________________

17 See the Concluding Observations section for a discussion about this discrepancy.

of funding for WHR was seen for NIH intramural grants (6.5 percent) and the aggregate of extramural and internal grants (see Figure 4-1). Overall, NIH grant funding has steadily increased FY 2013–FY 2023 in both dollars spent and the number of projects funded. However, the proportion of funding for research related to women’s health remained low and decreased during the same period (Figure 4-2 and Appendix Table A-1). Of the $33 billion NIH spent on WHR grants in the analysis period, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) accounted for approximately $9.2 billion,

NOTE: Percentages in both panels indicate the specific proportion of spending (Panel A) or grants (Panel B) designated as women’s health research.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) $5.3 billion, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) $4.1 billion, and the other ICs about $2 billion or less (see Figure 4-3).

NOTE: CIT = Center for Information Technology; FIC = Fogarty International Center; ICO = Institute, Center, or Office; NCATS = National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NCCIH = National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NEI = National Eye Institute; NHGRI = National Human Genome Research Institute; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIAAA = National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIAMS = National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIBIB = National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; NICHD = Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDA = National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIDCD = National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; NIDCR = National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; NIDDK = National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIEHS = National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIGMS = National Institute of General Medical Sciences; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health; NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NINR = National Institute of Nursing Research; NLM = National Library of Medicine; OD = Office of the Director; RMOD = Road Map/Common Fund.

Grant Funding for WHR by NIH Institute or Center

The low proportion of funding for WHR was seen across all ICs (see Figure 4-4 and Appendix Table A-2). The temporal trend of a flat or decreasing proportion of funding for WHR was seen in each IC, including those with the largest portfolio of spending on it (see Appendix Figure A-2). The IC with the largest proportion of its funding allocated to WHR was the NICHD (37 percent of its spending); all other ICs spent less than 20 percent, and many less than 10 percent, on WHR (see Figure 4-4 and Appendix Table A-2).

Grant Mechanisms for Funding WHR

All NIH grant funding is awarded through a selection of established mechanisms, each designated to fund a certain type of research project or program. These include extramural research (R and P grants); cooperative agreements (U grants); fellowship, training, and training center activities (F, K, and T grants); and intramural research activities (Z grants) (Table 4-1). WHR funding is provided across ICs through a variety of grant mechanisms, though it is predominantly through research project grants (R series) (Figure 4-5).

Distribution of NIH Grant Funding for Women’s Health Conditions

To understand how NIH grant funding for WHR has been spent over time, the committee selected funding patterns for a list of 67 conditions (and a category for other diseases and conditions) it prespecified as relevant (see Appendix Table A-3). Given the committee’s time frame, resources, and lack of access to full grant content, it was not able to prorate spending on each grant by topic, a limitation noted in the current spending category reporting by NIH. This will be an essential step to include in future assessments to gain a clearer picture of spending on each condition (see Appendix A for additional limitations of the committee’s analysis).

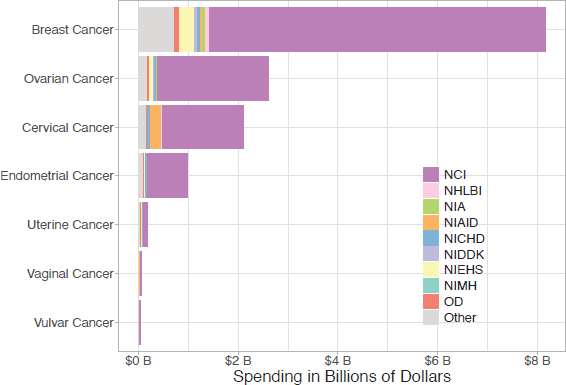

NIH grants funded to study conditions relevant to women’s health favored certain conditions; among the studied conditions, the 10 highest funded included breast cancer and some female-specific cancers, pregnancy and infertility, and perimenopause and menopause, as well as conditions that also affect men, such as HIV/AIDS, diabetes, and depressive disorders (see Figure 4-6). For FY 2013–FY 2023, the women’s health condition that received the most grant funding was breast cancer, with most granted by NCI. Relatively disparate rates of funding were seen for other female-specific cancers, with uterine, vaginal, and vulvar cancer receiving far less research investment (see Figure 4-7). The second most funded area among

NOTE: CIT = Center for Information Technology; FIC = Fogarty International Center; NCATS = National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; NCCIH = National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NEI = National Eye Institute; NHGRI = National Human Genome Research Institute; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIAAA = National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIAMS = National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIBIB = National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; NICHD = Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDA = National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIDCD = National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders; NIDCR = National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; NIDDK = National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIEHS = National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIGMS = National Institute of General Medical Sciences; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health; NIMHD = National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NINR = National Institute of Nursing Research; NLM = National Library of Medicine; OD = Office of the Director; RMOD = Road Map/Common Fund.

TABLE 4-1 Types of NIH Grants

| Activity Code | Purpose | |

|---|---|---|

| Extramural Research | ||

| R | Research Projects | Research project grants may be awarded for discrete, specific research projects to individuals at universities, medical and other health professional schools, colleges, hospitals, research institutes, for-profit organizations, and government institutions. Typically, these grants are awarded for 3–5 years. The most common award is R01. |

| P | Program Project/Center Grants | “Program project/center grants are large, multi-project efforts that generally include a diverse array of research activities.” |

| Cooperative Agreements | ||

| U | Cooperative Agreements | Cooperative agreements are “a support mechanism frequently used for high-priority research areas that require substantial involvement from NIH program or scientific staff.” |

| Fellowships, Training, Training Centers | ||

| F | Fellowships | Fellowships “provide individual research training opportunities (including international) for trainees at the undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral levels.” |

| K | Career Development Awards | Career Development awards “provide individual and institutional research training opportunities (including international) to trainees at the undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral levels.” |

| T | Institutional Training Grants | Institutional Training awards enable institutions “to provide individual research training opportunities (including international) to trainees at the undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral levels.” |

| Intramural Research | ||

| Z | Intramural Research | Z grants support research activities of NIH intramural researchers. |

SOURCES: Excerpts from NIAID, 2023; NIH, 2017a,b,c, 2023c.

selected conditions related to women’s health was HIV/AIDS research, with most granted by NIAID and NICHD. Relatively low rates of funding were seen for many other conditions that affect women differently than men, such as coronary heart disease, and female-specific conditions, such as endometriosis, PCOS, and fibroids.

In analyses of funding trends over time, the relative predominance of funding for the 10 highest women’s health conditions was fairly consistent for FY 2013–FY 2023, except for an increase for pregnancy-related conditions

NOTES: Dollars are presented in billions. Percentages represent the portions of women’s health research funded by different grant mechanisms. FY = fiscal year.

(see Figure 4-8). Trends in funding for cancers specific to and more common in women were relatively flat for FY 2013–FY 2023 (see Figure 4-9). For prevalent chronic conditions that affect both sexes, funding oriented toward women’s health increased over time for some but not all (see Figure 4-10). Substantial increases were seen for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, coronary heart disease, and diabetes, with relatively little or no change for osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and pulmonary hypertension. Among other select female-specific conditions, funding increased for perimenopause and menopause and endometriosis but was static for conditions such as fibroids, pelvic inflammatory disease, PCOS, premature ovarian failure, and menstrual disorders (see Figure 4-11). Among select autoimmune diseases relevant to women’s health, systemic lupus erythematosus was the highest funded, though it experienced a recent decrease, and funding for the others was relatively constant (see Figure 4-12).

Overall, when compared to the steady and significant rise in total NIH grant funding for FY 2013–FY 2023 (see Figure 4-1), the proportionate funding for women’s health in general, and for funding that is specific to many morbid and fatal conditions, has not kept pace. These trends have contributed to the persistently low and even decreasing rate of funding for WHR that is most recently estimated at 7.9 percent of total NIH funding (see Figure 4-1). Notably, the funding for several conditions, such as diabetes, pregnancy-related conditions, and menopause and perimenopause, appeared

NOTE: NCI = National Cancer Institute; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NICHD = Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDDK = National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIEHS = National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health; OD = Office of the Director.

NOTE: NCI = National Cancer Institute; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NICHD = Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDDK = National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NIEHS = National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health; OD = Office of the Director.

to derive from multiple IC sources (see Figure 4-6), indicating that these have not been consistently identified as within the purview of any single IC. The relatively scant funding for the majority of the 67 conditions determined to be relevant to women’s health suggests that they have also lacked a consistent IC source of funding or, in some cases, any IC funding at all.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

In summary, the committee’s analysis of NIH funding for WHR found that despite steady increases in total grant funding over the past 11 years, the proportion for WHR has remained low, at an overall average of 8.8 percent, and decreased over time, from 9.7 percent in FY 2013 to 7.9 percent in FY 2023. This analysis produced consistently lower estimates than those NIH reported for two main reasons: the analysis employed recently available advanced tools that allowed for more reliably identifying grants related to women’s health and used an approach that avoids duplicate or multiplicative counting of grants when tabulating total funding amounts. Differences could have also occurred due to the definitions used. Since the committee did not have access to NIH’s full definition for the women’s health RCDC category, it is difficult to determine if some of the variance resulted from definitional differences of what constitutes WHR. Another limitation of the analysis is the inability to determine an ideal funding level or percent allocation for WHR. The nature and scope of conditions and diseases that exclusively or predominantly affect women are recognized to change over time, and highly prevalent conditions and diseases affecting both women and men can involve varying degrees of sex-divergent presentations and outcomes in ways that have yet to be fully

understood, thus warranting more research (Pattisapu et al., 2021; Taqueti, 2018). Additionally, conditions and diseases with sex-differential effects can emerge from year to year—and involve a prevalence and burden in women that require time and effort to estimate (Bai et al., 2022; Cantrell et al., 2024). For all of these reasons, the ideal research funding level or allocation could not be reliably predicted. Notwithstanding these limitations, the analysis produced reproducible results regarding observable trends in NIH funding for WHR over time.

In addition to the overall low and declining funding rates for WHR, the analysis revealed several additional key findings. Although many research areas pertinent to women’s health could fall under the purview of the existing ICs, the rate of funding was low across all ICs. The limited funds granted for WHR have had markedly uneven distribution across the major conditions affecting women’s health. Furthermore, the analysis showed that many conditions that predominantly or exclusively affect women’s health have received relatively little to no funding. Taken together, these findings indicate the need for substantially augmented funding for WHR across the existing ICs and a well-defined and stable funding home to enable research on underfunded or unfunded conditions affecting up to half the U.S. adult population.

REFERENCES

Bai, F., D. Tomasoni, C. Falcinella, D. Barbanotti, R. Castoldi, G. Mulè, M. Augello, D. Mondatore, M. Allegrini, A. Cona, D. Tesoro, G. Tagliaferri, O. Viganò, E. Suardi, C. Tincati, T. Beringheli, B. Varisco, C. L. Battistini, K. Piscopo, E. Vegni, A. Tavelli, S. Terzoni, G. Marchetti, and A. D. Monforte. 2022. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: A prospective cohort study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 28(4):611.e619–611.e616.

Baird, M. D., M. A. Zaber, A. Chen, A. W. Dick, C. E. Bird, M. Waymouth, G. Gahlon, D. D. Quigley, H. Al-Ibrahim, and L. Frank. 2021. The WHAM report: The case to fund women’s health research: An economic and societal impact analysis. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Cantrell, C., C. Reid, C. S. Walker, S. J. Stallkamp Tidd, R. Zhang, and R. Wilson. 2024. Post-COVID postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): A new phenomenon. Frontiers in Neurology 15.

Cebotari, E., and N. Praskievicz. 2024. NIH’s research, condition, and disease categorization (RCDC) system. Presentation to the NASEM Committee on the Assessment of NIH Research on Women’s Health, Meeting 2 (January 25, 2024). https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/docs/D0195AEF81CCEAE1E0BEA79C3AA37C7D6EE52D5DFAF3?noSaveAs=1 (accessed February 26, 2024).

Clayton, J. A. 2023. NASEM Committee on the Assessment of NIH Research on Women’s Health. Presentation to NASEM Committee on the Assessment of NIH Research on Women’s Health, Meeting 1 (December 14, 2023). https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/41452_12-2023_assessment-of-nih-research-on-womens-health-meeting-1-part-3 (accessed August 22, 2024).

iCite. n.d. iCite. https://icite.od.nih.gov/ (accessed August 15, 2024).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Exploring the biological contributions to human health: Does sex matter? Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Lauer, M. 2018. RCDeCade: 10 Years and Still Counting. https://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2018/06/12/rcdecade-10-years-and-still-counting/ (accessed August 7, 2024).

Lauer, M. 2024. FY 2023 by the Numbers: Extramural Grant Investments in Research. https://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2024/02/21/fy-2023-by-the-numbers-extramural-grant-investments-in-research/ (accessed August 11, 2024).

Liu, K. A., and N. A. Mager. 2016. Women’s involvement in clinical trials: Historical perspective and future implications. Pharmacy Practice 14(1):708.

Mirin, A. A. 2021. Gender disparity in the funding of diseases by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Journal of Women’s Health 30(7):956–963.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2022. Enhancing NIH research on autoimmune disease. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2024a. Discussion of policies, systems, and structures for research on women’s health at the National Institutes of Health: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2024b. Overview of research gaps for selected conditions in women’s health research at the National Institutes of Health: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases). 2023. Cooperative agreements (U). https://www.niaid.nih.gov/grants-contracts/cooperative-agreements (accessed August 22, 2024).

NICHD (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development). n.d. Implementing a Maternal Health and pregnancy Outcomes Vision for Everyone (IMPROVE) initiative. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/supported/IMPROVE (accessed August 7, 2024).

NIH (National Institutes of Health). n.d.-a. About RCDC. https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending/rcdc (accessed August 7, 2024).

NIH. n.d.-b. Frequently Asked Questions About Research, Condition, Disease Categorization (RCDC) System and the NIH Categorical Spending Reports. https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending/rcdc-faqs (accessed August 7, 2024).

NIH. n.d.-c. RCDC: Categorization Process. https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending/rcdc-process (accessed August 7, 2024).

NIH. n.d.-d. Report: Frequently Asked Questions. https://report.nih.gov/faqs (accessed October 2, 2024).

NIH. 2017a. Individual Fellowships (F) Kiosk. https://researchtraining.nih.gov/programs/fellowships (accessed August 22, 2024).

NIH. 2017b. Institutional Training Grants (T) Kiosk. https://researchtraining.nih.gov/programs/training-grants (accessed August 22, 2024).

NIH. 2017c. Research Career Development Awards (K) Kiosk. https://researchtraining.nih.gov/programs/career-development (accessed August 22, 2024).

NIH. 2023a. Impact of NIH Research: Direct Economic Contributions. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/impact-nih-research/serving-society/direct-economic-contributions (accessed August 7, 2024).

NIH. 2023b. News Release: NIH Establishes Maternal Health Research Centers of Excellence. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-establishes-maternal-health-research-centers-excellence (accessed September 8, 2023).

NIH. 2023c. Type of Grant Programs. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/funding_program.htm (accessed August 22, 2024).

NIH. 2024a. Estimates of Funding for Various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories (RCDC). https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/ (accessed August 7, 2024).

NIH. 2024b. New FY 2023 Categorical Spending Data Are Now Available. https://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2024/05/14/new-fy-2023-categorical-spending-data-are-now-available/ (accessed August 7, 2024).

OPA (Office of Portfolio Analysis). 2021. Office of Portfolio Analysis strategic plan: Fiscal years 2021–2025. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health.

ORWH (Office of Research on Women’s Health). n.d. Advancing NIH Research on the Health of Women: A 2021 Conference. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/research/2021-womens-health-research-conference (accessed August 7, 2024).

ORWH. 2023. Report of the Advisory Committee on Research on Women’s Health, fiscal years 2021–2022: Office of Research on Women’s Health and NIH support for research on women’s health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health.

Pattisapu, V. K., H. Hao, Y. Liu, T. T. Nguyen, A. Hoang, C. N. Bairey Merz, and S. Cheng. 2021. Sex- and age-based temporal trends in Takotsubo Syndrome incidence in the United States. Journal of the American Heart Association 10(20):e019583.

Salari, N., H. Ghasemi, L. Mohammadi, M. H. Behzadi, E. Rabieenia, S. Shohaimi, and M. Mohammadi. 2021. The global prevalence of osteoporosis in the world: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 16(1):609.

Taqueti, V. R. 2018. Sex differences in the coronary system. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1065:257–278.