A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health (2025)

Chapter: 8 A Workforce to Advance Women's Health Research

8

A Workforce to Advance Women’s Health Research

The committee’s charge included providing recommendations to improve training and education efforts to build, support, and maintain a robust women’s health research (WHR) workforce (i.e., researchers who undertake such research, not only women researchers) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and recommendations to achieve an NIH-wide workforce to effectively solicit, review, and support WHR. The committee was asked to look broadly at NIH’s structure (extra- and intramural) systems and review processes within all domains, including workforce. The NIH intra- and extramural workforce is essential—without a properly trained and supported workforce, the nation cannot address the research needs and gaps highlighted in Chapters 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7. This chapter reviews some of NIH’s programs, grants, and processes that affect the WHR workforce. For this report, the “workforce” includes extramural researchers who could or have applied for NIH funding and intramural staff at NIH: scientists and researchers who are part of the NIH Intramural Research Program (IRP), NIH program staff who oversee grants and programs, and other NIH staff, such as in the Center for Scientific Review, who organize, review, and administer peer review. The committee focused on the extramural research workforce and needed support, as that is where NIH spends the majority of its research dollars and where data are available to assess. However, the committee recognizes that the entire NIH workforce has a critical role in shaping the WHR workforce nationally.

EXTRAMURAL WORKFORCE

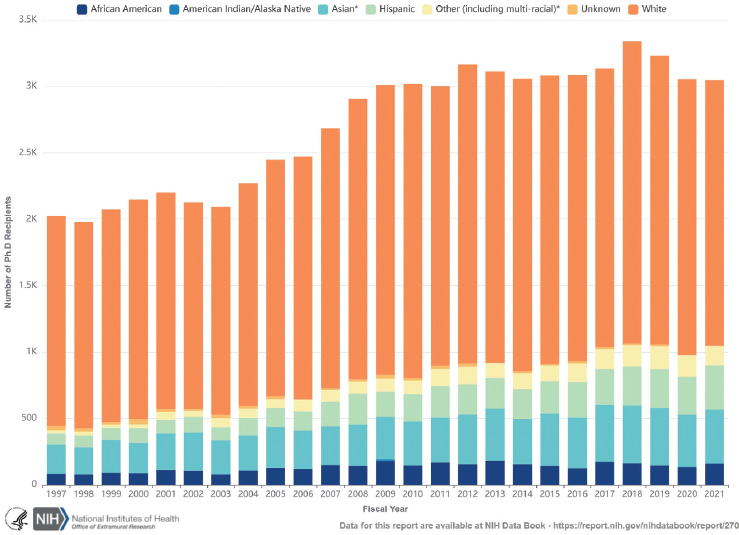

To ensure a diverse workforce, including those with expertise in women’s health and sex differences research, workforce development grants are essential to support researchers’ development and ability to continue to progress in their research in a given field (see Figure 8-1 for trends of funded career development grants). The role of NIH in workforce development is crucial as the primary funder of biomedical research in the United States; it is essential to ensure these funds are allocated to maximize their effect on research discoveries and researchers have the needed experiences, training, and expertise from high school forward.

NIH provides a range of grants to extramural researchers that vary by career stage, focus, length, funding level, and mechanism. Not all NIH Institutes and Centers (ICs) offer all grant types, and the number they award varies over time (see Table 8-1 for types of workforce support/development grants). When looking at all grants, including for career development, NIH awards over 58,000 extramural grants each year, representing nearly 83 percent of its budget, that directly support more than 300,000

SOURCE: NIH, 2024i.

TABLE 8-1 Categories for Fellowship, Training, and Training Center Grants

| Types of NIH Grants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Activity Code | Purpose | |

| Fellowships, Training, Training Centers | ||

| F | Fellowship Programs | Fellowships provide individual research training opportunities (including international) for those at the undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral levels. |

| K | Research Career Development Programs | Research Career Development awards provide individual and institutional research training opportunities (including international) to those at the undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral levels. |

| T | Institutional Training Programs | Institutional Training awards enable institutions to provide individual research training opportunities (including international) for those at the undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral levels. |

SOURCES: Data from NIH, 2017a,b,c.

NOTES: Specific grant awards and programs in other grant mechanisms also support workforce development, such as some D (Institutional Training and Director Program Projects), R (Research Projects), and supplemental grant awards. More information on these grants is available at https://researchtraining.nih.gov/ (accessed August 5, 2024).

researchers at more than 2,700 different institutions (Lauer, 2024; NIH, 2023a, 2024a). Who can obtain these grants depends heavily on their understanding of the NIH application process, expertise in research, support offered by their home institution, and time available to apply. Whom NIH funds also depends on the priorities of the IC to which the researcher is applying—topics that do not align with an IC’s priorities or purview are less likely to be funded by it. As previous chapters noted, this is problematic because many women’s health conditions do not align with the purview or priorities of ICs, leaving such researchers with fewer funding opportunities.

Based on the committee’s funding analysis (see Chapter 4 and Appendix A), from 2013 to 2023, extramural funding on WHR was predominantly research project grants (R series). Workforce training and development grants that focused on WHR had a low level of funding. Across ICs 2013–2023, $1.01 billion (3.05 percent) was spent on career development (K series), $0.16 billion (0.49 percent) on fellowships (F series), and $0.12 billion (0.37 percent) on training grants for WHR; the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) invested the most on career development grants, followed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the Office of the Director (OD). For training grants, NICHD invested the most, followed by NCI and the

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). NCI invested the most in fellowships, followed by NICHD and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH).

Whom Does NIH Fund?

This section briefly summarizes the makeup of the NIH extramural workforce by sex, race, and ethnicity as reported by NIH (see later in this chapter for an overview of the intramural workforce). Trends of NIH grant funding can serve as one indicator of the level of support for WHR, including support of investigators from minoritized populations. Ensuring a diverse pool of funded researchers across sex, race, ethnicity, and other demographic characteristics can lead to a broader range of perspectives and innovative approaches in research, including for WHR. When available, data at the intersection of gender/sex and race and ethnicity are reported.

Distribution of Grantees by Sex

NIH tracks the sex but not the gender identity of extramural researchers receiving grants. For fiscal year (FY) 2016–2022, female principal investigators (PIs) supported by R01-equivalent grants1 increased from 29.4 to 34.0 percent. This represents an average annual increase of about 0.8 percentage points (see Figure 8-2) (ORWH, 2023).

For all research project grants (RPGs), the proportion of female PIs grew from 30.8 percent in 2016 to 36.2 percent in 2022, with an average annual increase of 0.9 percentage points (ORWH, 2023), and the percentage of female PIs on R01-equivalent grants who identified as non-Hispanic White decreased from 70.6 percent to 63.0 percent, with a rise in the percentage of female PIs from Asian, Hispanic, Black, and other racial and ethnic groups. The NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) reported that during that FY 2016–FY 2022 period, 32 percent of PIs supported on research career, other research, and RPG awards were female and 31 percent or fewer were supported by center grants, Small Business Innovation Research grants, and Small Business Technology Transfer awards (ORWH, 2023). In FY 2021, women made up 60 percent of the postdoctoral institutional trainees, up from 56 percent in FY 2020 and 2022. Female postdoctoral fellows increased from 50 percent in FY 2020 to 57 percent in FY 2021 but then dropped slightly to 55 percent in FY 2022. Female predoctoral trainees decreased from 58 percent in FY 2020 to 53 percent in FY 2021 before rising again to 61 percent in FY 2022 (ORWH, 2023).

___________________

1 The Research Project (R01) grant is an award to support a discrete, specified, circumscribed project to be performed by the investigator(s) in an area representing their specific interest and competencies, based on NIH’s mission.

NOTES: Data were drawn from the frozen Success Rate Demographic file on February 14, 2023. Data were produced by the Division of Statistical Analysis and Reporting within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Extramural Research’s Office of Research Reporting and Analysis. Percentages do not add up to 100 percent because of rounding. R0-1-equivelent grants are defined in Annex B of the original source. Data on sex profiles are maintained by the investigator in the NIH Electronic Research Administration (eRA) system and are subject to change. Data include direct budget authority only and include all competing applications.

SOURCE: ORWH, 2023.

Since FY 2016, female PIs accounted for 50 percent or more of those receiving research career and training awards, and in FY 2022, they had funding rates comparable to male PIs (see Figure 8-3). However, for R01-equivalent grants between FY 2016 and FY 2022, female PIs represented 31–34 percent of applicants and 29–34 percent of recipients. In FY 2022, female PIs constituted 48 percent of early-stage R01-equivalent grant recipients (ORWH, 2023) and received about the same or higher funding amounts for R01-equivalents 2016 to 2022. Male PIs generally receive higher average funding overall than their female counterparts and are more likely to receive certain types of grants, such as center grants. While funding rates for female PIs from minoritized backgrounds have improved since FY 2016, these populations are still funded at lower rates than non-Hispanic White female PIs (ORWH, 2023).

NOTES: Data from NIH IMPAC Pub File. Data were produced by the Division of Statistical Analysis and Reporting within the NIH Office of Extramural Research’s Office of Research Reporting and Analysis and drawn on December 16, 2022. Each data point reflects only current dollars and is not adjusted for inflation. R01-equivelent grants are defined in Annex B of the original source. Research grants are defined as extramural awards made for research centers, research projects, Small Business Innovation Research/Small Business Technology Transfer program grants, and other research grants. Research grants are defines by the following activity codes: R, P, M, S, K, U (excluding UC6), DP1, DP2, DP3, DP4, DP5, DP42, and G12. Analysis is restricted to Principle Investigators who reported their sex. Data on sex profiles are maintained by the investigator in the NIH eRA system and are subject to change.

SOURCE: ORWH, 2023.

Race and Ethnicity

A 2011 review of grants awarded over a 7-year period revealed that, for independent research grants, applications from White PIs were 1.7 times more likely to be funded than those from Black PIs (Ginther et al., 2011). A 2019 follow-up study showed no change (Hoppe et al., 2019) and that the decision to discuss applications at a study section and the impact score combined accounted for 42 percent of gap in funding, with the proposed research topic accounting for 20 percent. A 2018 analysis found that factors related to higher success rates in general, such as being a full professor or

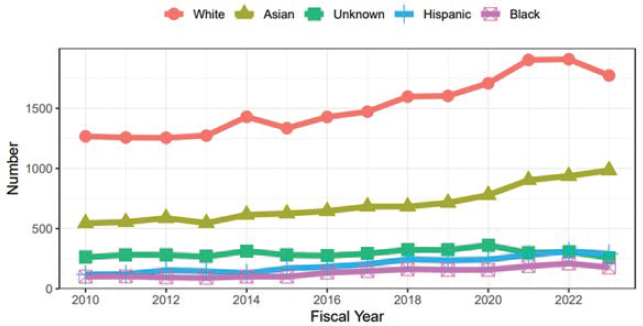

SOURCE: NIH, 2024e.

publishing with coauthors who publish in the upper quartile of their fields, did not close the funding gap (Ginther et al., 2018). See Figures 8-4 and 8-5 for funding by race and ethnicity for NIH grants.

A 2018 Government Accountability Office (GAO) study also found disparities for underrepresented racial and ethnic groups and female investigators from 2013 through 2017 (GAO, 2018). In 2017, about 17 percent of Black, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) applicants combined for large grants received them, compared to approximately 24 percent of Hispanic or Latino, 24 percent of Asian, and 27 percent of White applicants. The GAO report concluded that “NIH has taken positive steps such as establishing the position of Chief Officer of Scientific Workforce Diversity, who in turn created a strategic workforce diversity plan, which applies to both extramural and intramural investigators. The plan includes five broad goals for expanding and supporting these investigators. However, NIH has not developed quantitative metrics, evaluation details, or specific time frames by which it could measure the agency’s progress against these goals” (GAO, 2018).

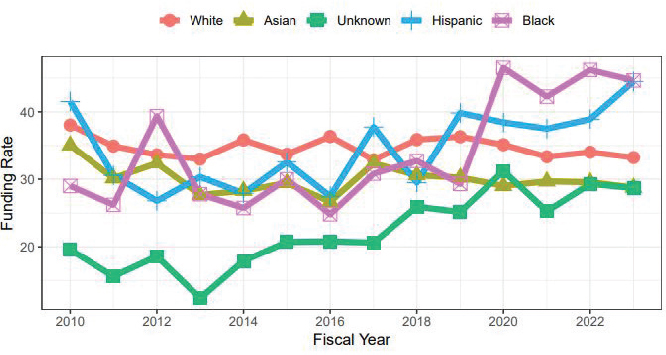

NIH has developed programs and initiatives to close these gaps and is making some progress (NIH, 2022b, 2024b, n.d.-d). In July 2024, NIH published a report on mentored career development application (K award)

NOTES: From 1982 to 2000, the racial categories used in the Survey of Earned Doctorates included “Asian and Pacific Islander.” In 2001, the survey was revised, and “Asian” and “Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander” became separate categories. For the purposes of reporting, Native Hawaiians are included in the “Other” category.

SOURCE: NIH, 2023c.

funding rates2 (Figures 8-6 and 8-7) (Lauer and Roychowdhury, 2024). For scientists designated as a PI on at least one K application submitted in FY 2011 and FY 2023, Black applicants in FY 2023 were more likely to submit a K01 application and less likely to submit K08 or K23 applications compared to White applicants. Black applicants were more likely to submit proposals including human participants and less likely to submit proposals including animal models (Lauer and Roychowdhury, 2024).3 This analysis

___________________

2 Data include K01, K08, K23, K25, and K99 career development awards. Some ICs use the K01 mechanism to enhance workforce diversity.

3 A separate analysis by NIH showed that Black applicants were more likely to be associated with topics such as health disparities, disease prevention and intervention, socioeconomic factors, health care, lifestyle, psychosocial, adolescent, and risk and that, in general, applications using those terms were less likely to be funded than topics such as neuron, corneal, cell, and iron (Hoppe et al., 2019).

SOURCE: Lauer and Roychowdhury, 2024.

did not include data on NHPI and AIAN researchers, likely the result of the larger problem of AIAN and NHPI researchers being underrepresented in NIH grants.

These data show applicants and funding rates from underrepresented groups trending upward. However, AIAN and NHPI researchers are not visible in NIH data reporting of grant funding for almost all years (NIH, 2022c). This is also the case when looking at the funding mechanisms and who is funded by race and ethnicity, including research grants, training grants, and fellowships. Overall, while the race and ethnicity gaps in funding are beginning to narrow, significant gaps for certain groups persist.

SOURCE: Lauer and Roychowdhury, 2024.

Summary of Whom NIH Funds

Unfortunately, data on racial and ethnic trends in funding among women are not readily available on the NIH dashboard. Such data would indicate whether there are multiplicative effects of being a woman and racially minoritized in the NIH workforce. However, given research on the scientific workforce and trends in the general workforce, it would be expected that AIAN and Black women in particular are funded at lower rates than White women (Kaiser, 2023; Malcom et al., 1976; Nguyen et al., 2023). Furthermore, the data do not indicate any information on transgender or nonbinary identities among investigators, and the measurement of sex is inadequate to assess gender.

NIH EXTRAMURAL GRANTS TO DEVELOP AND SUPPORT WHR WORKFORCE

In this section, the committee reviews some career development grants awarded by NIH and how they affect the initiation and sustainability of research careers. This section also reviews workforce development and support programs for the NIH extramural workforce that specifically focus on women or on sex differences (see Table 8-2). It was beyond the scope of this report to review all NIH programs that could potentially impact the WHR workforce.

TABLE 8-2 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Extramural Workforce Programs Focusing on Women’s and/or Sex Differences Research Reviewed

| Program | Target Population | Type of Award | Duration* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) | Early-career faculty who have recently completed clinical training or postdoctoral fellowship and plan to conduct interdisciplinary basic, translational, behavioral, clinical, and/or health-services research relevant to women’s health | K12, Internal K | Up to 5 years |

| Women’s Reproductive Health Research (WRHR) | Obstetrician-gynecologists who recently completed postgraduate clinical instruction | K12 | 5 years |

| Reproductive Scientist Development Program (RSDP) | Early-career physician-scientists | K12 | Up to 5 years |

| Specialized Centers of Research Excellence (SCORE) on Sex Differences | Any individual(s) with the skills, knowledge, and resources necessary to carry out the research | U54 | 5 years |

NOTE: * Duration based on the most recent NIH Request for Proposal for each program.

SOURCES: Data from HHS, 2018; NICHD, 2023b; NIH, 2022d,e, 2024f,g.

Research Career Development Awards (K)

I am fortunate to have experienced over a decade some kind of support from the NIH and it would not have been possible without a K award. I see far too many capable junior researchers fall away because of the lack of time to really pursue important research questions and because the clinical mission is what is emphasized.

—Participant at committee information-gathering meeting

External Research Career Development Program K awards are available to early-career researchers to apply for mentored research projects. They support and protect time for faculty to develop research skills and ultimately ensure a pool of highly trained research scientists and enable scientists with diverse backgrounds to enhance their careers in biomedical research and provide support for senior postdoctoral fellows or faculty-level candidates. Individual ICs fund K awards for up to 5 years, and the specific terms vary, particularly regarding salary limitations. K awards fall into three categories (see Appendix B for examples):

- Mentored awards to individuals are intended primarily for researchers at the beginning of their careers and provide a transition to full independent research awards.

- Independent or nonmentored awards provide protected research time for midcareer or even senior faculty to enhance their research potential.

- Institutional awards provide mentored experiences for multiple individuals.

The objective of K awards is to provide candidates with the experience and support needed to be able to conduct their research independently and be ready to compete for major grant support. These are traditional mentored research awards, and applicants are judged on their ability to perform research and publish, the mentor’s ability to advance the careers of their mentees, and their institutional support. External K awards are the mechanism for most Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) awardees (see later in the chapter for more information) to progress in developing into independent researchers. However, not all K awardees continue to conduct research after their award ends (Jagsi et al., 2017). The reasons for this attrition for M.D.s and Ph.D.s are multifaceted but center around the need for higher income for researchers to pay off large training debts, lack of a tenure or other funded position at their home or other research institutions, inability to become independent from their mentors (e.g., acquisition of R01 or R01 equivalent), and caregiving responsibilities (Bates et al., 2023; Jagsi et al., 2017). This is an especially

salient issue in women’s health and sex differences research. However, some WHR-focused workforce programs demonstrated greater success in retaining clinician-researchers (see later in this chapter for more information).

A shortcoming of the mentored K awards is that there is no direct financial support for the mentor, limiting their ability to guide their mentees. In addition, support for K awardee salaries is capped at $100,000 per year, which is often not sufficient for physicians to juggle debt repayment and the cost of living near most academic medical centers (NIH, 2019, 2024j). After 5 years of K funding, some awardees may not be ready to launch an independent research program with R awards, with no clear mechanisms to obtain supplemental funding to extend the mentored training period to achieve independent funding.

This section discusses three K award workforce development programs that support WHR. All are either administered by or offered in coordination with ORWH.

BIRCWH

Through a partnership among ORWH and other Institutes, Centers, and Offices (ICOs), the BIRCWH career development K12 program was established in 2000 (ORWH, n.d.-a). It focuses on training early-career faculty, the BIRCWH scholars, and provides them with the opportunity to develop research skills to investigate women’s health and sex differences. The main goal is to provide early-career faculty with protected time to conduct research, write manuscripts, and obtain peer-reviewed funding to advance the understanding of this research (ORWH, n.d.-a). The program has played a significant role in launching the current generation of researchers who go on to become tenured professors and lead impactful research on women’s health and sex differences nationwide (Berge et al., 2022; Choo et al., 2020; Nagel et al., 2013). In turn, those researchers will acquire the expertise to train new researchers.

A key component of the program is mentorship by senior faculty who share interests in women’s health and sex and gender differences and have obtained peer-reviewed funding (NIH R01s or an equivalent). The program supports scholars in interdisciplinary basic, translational, behavioral, clinical, and health services research on these topics. Individuals who have completed clinical training or a postdoctoral fellowship and are within 6 years of their terminal degrees or have not had protected time to research since that degree are eligible; they will plan and conduct relevant research within their discipline.

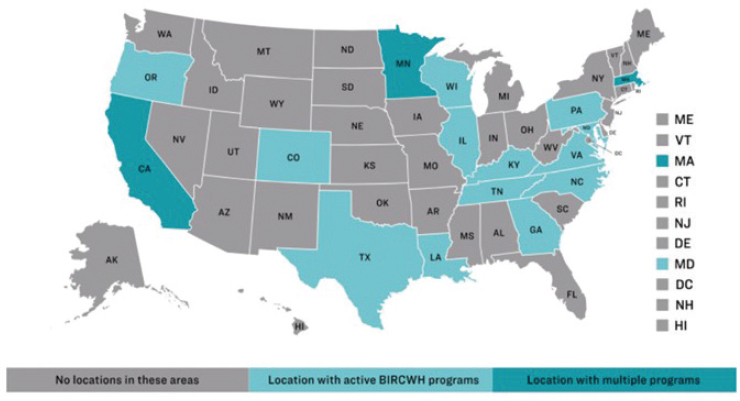

Since its inception in 2000, over 750 BIRCWH scholars have received career development training (ORWH, n.d.-a). ORWH and its partner ICs provide over $15 million per year to the 19 active BIRCWH programs (see

SOURCE: ORWH, n.d.-a.

Figure 8-8).4 For example, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) and National Institute on Drug Abuse provide grant management for BIRCWH awards (ORWH, n.d.-a).5

BIRCWH has focused on supporting early-career faculty, typically newly appointed assistant professors. Initially, it provided support for four scholars at each program site. Over time, the program budget has changed, resulting in a reduction or addition of the number of scholars per site (NIH, 2020). Starting in FY 2023, the program expanded to include a postdoctoral fellow (clinical degree, Ph.D., or comparable degree) or instructor-level faculty for each BIRCWH program for 1 additional year of support to obtain additional methodological training and conduct a mentored research project (HHS, 2024). The April 2024 funding announcement for renewal of the grants includes a budget in direct dollars (not including indirect costs) of $840,000 per program, which will fund up to five scholars each (HHS, 2024) This increase in sponsored scholars per program could have lasting impact on the size of the workforce of women’s health researchers with

___________________

4 For active 2024 BIRCWH programs, see https://orwh.od.nih.gov/our-work/building-interdisciplinary-research-careers-in-womens-health-bircwh/funded-programs-and-principal-investigators (accessed June 11, 2024).

5 Past cosponsors include NICHD, NCI, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIAID, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), NIMH, and the Office of AIDS Research.

the goal of improving women’s health and understanding sex differences across the nation.

One unique aspect of this program is mentorship by a senior faculty member with experience in obtaining NIH or equivalent funding and expertise in mentoring early-career researchers. However, a significant shortcoming is that they receive no funds to cover their time and effort. In addition to the primary mentor, the BIRCWH program requires “mentoring teams” who provide career advice, additional research direction, and education about how to navigate early careers at research institutions. It also requires scholars to write career development plans that are reviewed by their mentors at least twice a year to ensure they are progressing and identify challenges that need to be addressed to advance their research and careers. Scholars across the sites are networked and work together through quarterly virtual meetings organized by ORWH and BIRCWH programs on issues related to career advancements. ORWH brings all scholars and program directors to the NIH campus each year for in-person career advancement education and scientific exchanges.

An important benefit of BIRCWH is that it educates researchers on how to integrate sex and gender differences into clinical research and connects scholars to national resources. A 2020 study found that 45 percent of BIRCWH institutions offered education on integration in clinical translational research; of those, 54 percent offered in-person training and 31 percent offered content within existing for-credit courses (Libby et al., 2020).

Individual programs have conducted their own assessments to identify best practices and program outcomes and an overall evaluation of the success of the BIRCWH scholars in obtaining funds or success in academic research. One program conducted an electronic survey and in-person discussions with BIRCWH program leaders and concluded that the programs have been highly successful; the most commonly cited factors associated with success were sufficient time for mentors and scholars to meet and the interdisciplinary and collaborative team mentoring approach (Guise et al., 2012). A 2017 study found that interdisciplinary teams helped BIRCWH scholars strengthen study designs, expand their research topics, and expose them to research areas in which they were not directly trained (Guise et al., 2017). Other benefits noted by scholars include opportunities to meet local and national investigators with whom they subsequently established research collaborations.

A 2017 review of BIRCWH found that mentoring plays a critical role in academic success. Fellows and faculty who are mentored are more likely to report greater job satisfaction, pursue and remain in an academic career, experience improvements in annual performance reviews, are more than two times more likely to be promoted to professor, and are two to three times more likely to become a PI on research grants. These outcomes

underscore the importance of mentored grant programs to developing a WHR workforce. One study found that BIRCWH directors identified persistence and resilience and developing community, networks, and other support opportunities as elements of scholar success and noted the critical role of mentors (Choo et al., 2020). A 2022 review evaluated 16 BIRCWH scholars against a comparison group of 17 non-BIRCWH scholars for traditional bibliometric impact (Berge et al., 2022). This review found that BIRCWH scholars had significantly more publications from pre- to post-BIRCWH experience and accelerated network growth, interdisciplinary collaborations, international citations, and policy impact. Specifically, BIRCWH scholars had a 38 percent grant award success rate in comparison to the NIH overall early-stage investigator rate of 29 percent.

Another study reviewed the Minnesota BIRCWH program and showed that a rigorous evaluation plan can increase the effectiveness of a research career development plan (Raymond et al., 2018). This study demonstrated the importance of a formal research career development program and found that 28 of 29 BIRCWH programs incorporated structured evaluations of mentoring and training components.

In summary, the BIRCWH program has successfully trained a workforce of investigators in women’s health and sex differences research. It provides protected time to perform research, write, and publish and oversight of scholars’ work and career progression by both mentors in their disciplines and program directors. In addition, the annual meeting of scholars from all programs enables them to share research, build collaborations, and gain perspectives on future career directions. The recent increase from two to five scholars for each program is a sufficient size to form a supportive and cohesive group for feedback on grant ideas and career advice.

However, BIRCWH could be strengthened. Although many of the programs function as stepping-stones for scholars to obtain an external K award and give them more time to develop an independent research career, it does prolong training. While the mentors have a history of or current NIH funding, they do not receive salary support for their mentoring, and as most seasoned mentors are keenly aware, it can take over 10 percent effort to train a mentee to become a successful independent researcher. In addition, the institution receives only 8 percent indirect costs for the BIRCWH training grant, which can disincentivize it from adding the needed extra support for administering these grants (HHS, 2024).

To improve the effectiveness of the BIRCWH program to further grow women’s health and sex differences research and the WHR workforce, NIH could consider expanding funding to allow mentors to be funded at 10 percent time to allow them time to be more effective and involved (i.e., an increased budget of approximately $100,000 per year for a mentoring component). Extending the term of support to up to 5 years per scholar—some

have only 2–3 years—would increase their ability to obtain and analyze data, publish a paper, and have the necessary research portfolio to write and obtain an R01 or equivalent grant. NIH could consider designing a K99/R00 for BIRCWH scholars to allow them to develop an independent research program and stay at the same institution or be able to move to another. This would allow for a two-tier program in which the scholar would be mentored within the institution and then be eligible for a K99/R00 within the same institution and become independent. One additional consideration would be to develop a Request for Application exclusive for BIRCWH graduates for independent funding related to women’s health and sex differences. This could be done through the NIH Foundation, which would allow for industry and philanthropy to partner with NIH in areas of women’s research and sex differences that are poorly funded and in need of novel interventions. See Chapter 9 for recommendations in this area.

Women’s Reproductive Health Research (WRHR) Career Development Program

The WRHR Career Development Program was launched in 1998 by NICHD with support from ORWH. It aims to enhance the research capabilities of newly trained obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYNs) (NIH, 1998, n.d.-b). It offers academic opportunities to receive state-of-the-art education and practical experience in women’s reproductive health research, spanning basic science, translational, and clinical research (NICHD, 2023b). This includes providing obstetrics and gynecology departments with investigators specializing in women’s reproductive health research.

Experienced investigators from well-established research programs offer an intellectual and technical base for mentoring WRHR scholars, addressing a wide range of basic and applied biomedical and biobehavioral sciences in obstetrics, gynecology, and partnering departments. The program sites for 2020–2025 include the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, University of Colorado, Duke University, Johns Hopkins University, Oregon Health & Science University, University of Pennsylvania, Stanford University, Harvard University, University of California, San Diego, University of Utah, Northwestern University, University of California, San Francisco, University of Washington, and Yale University (NICHD, 2023b).

The Gynecologic Health and Disease Branch in NICHD funds WRHR as part of NICHD’s K12 Institutional Career Development Program and is co-sponsored by ORWH, which supports local institutions that foster the development of OB/GYNs into independent research investigators (NIH, 2023d). WRHR covers the entire spectrum of obstetrics and gynecology research, including both general and specialized topics. Areas of focus

include maternal and fetal medicine, gynecologic oncology, reproductive endocrinology and infertility, and female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery, along with related fields, such as perimenopausal management and adolescent gynecology. This is essential because the OB/GYN workforce is small, and even fewer are clinician-scientists (see later in this chapter for more information). Funding is approximately $315,000 in direct costs per center each year for a maximum of 5 years (NIH, 2024l).

In 1998, WRHR started with 12 programs, growing to 20 in 1999, with three scholar slots per program for a total of 60 slots nationally. However, in 2024, there are only 15 programs with two slots per program for a total of 30 slots nationally, as a result of decreased funding. Since its inception, 28 institutions have participated; departmental benefits include developing and expanding research programs and the number of physician investigators (Coutifaris, 2024). Benefits to scholars are dedicated time for research, networking, and exposure to NIH (Coutifaris, 2024). However, there are drawbacks because the investment of time in the program by scholars (75 percent) is more than what is financially covered by the grants. In addition, mentor time is not covered (Coutifaris, 2024).

One group evaluated the WRHR program and found that 40 percent of scholars received additional independent NIH funding. Moreover, the return on investment was substantial, with 25 and 13 percent of scholars receiving at least one R01 or two to five R01 grants, respectively (McCoy et al., 2023). In addition, 81 percent continue to hold an academic position, with 75 percent achieving leadership in departmental or institutional positions, including vice chair (20 percent), chair (9 percent), or dean (3 percent). Fifty-two percent had participated in a NIH study section. The authors concluded that “the infrastructure provided by an institutional K award is an advantageous career development award mechanism for obstetrician-gynecologists,” who are predominantly women surgeons and noted that it “may serve as a corrective [program] for the known inequities in NIH funding by gender” (McCoy et al., 2023, p. 425.e1).

There are several opportunities to improve WRHR. For example, NICHD could allow flexibility for the percent of effort K awardees allocate to research (as some ICs do). Since OB/GYN is a surgical specialty that has a multistage certification process and examinations for 3–5 years after training, it is reasonable to consider flexibility in assigning the time dedicated to research effort. In addition, depending on the career path of the scholar (laboratory focused vs. clinical research focused), such flexibility would be advantageous for the overall development of their academic career. For example, developing laboratory researchers who have had no or minimal experience at the bench would likely need 75–100 percent dedicated time for research at the beginning. However, an M.D./Ph.D. starting out their faculty years as laboratory investigators may be equally

successful with 50–75 percent time. Allowing such flexibility (50–100 percent protected time for research, with the ability to change the percent during the program) based on the candidates’ qualifications, past experience in research, and lines of investigation being pursued could be beneficial for career development of surgeon-scientists.

Because the WRHR career development slots have been decreased by 50 percent since the program’s inception, it would be beneficial for the development of the WHR workforce to earmark a certain number of individual K awards for research focused on women’s health (with some being specifically earmarked for OB/GYNs).

Reproductive Scientist Development Program (RSDP)

RSDP, launched in 1988, is a national K12 career development program aimed at developing a “cadre of reproductive physician-scientists based in academic departments who could employ cutting-edge cell and molecular technologies to address important problems in the field of obstetrics and gynecology” and training physician-scientists with a particular emphasis on developing basic science skills (NICHD, 2023a). Early-career faculty receive mentored research opportunities to advance as independent physician-scientists.

RSDP is primarily funded by NICHD’s Fertility and Infertility Branch, with nongovernmental organizations and corporations offering additional support.6 It is administered centrally through the PI’s home institution and grants individual awards to scholars throughout the United States and Canada (Lo et al., 2023). RSDP scholars study a broad array of reproductive science topics, such as the molecular mechanisms of preeclampsia, transposons and piwi-interacting RNA and their roles in gynecological health and disease, and epigenetics mechanisms involved in the prenatal origins of age-related disease (NICHD, 2023a).

The program historically accepted approximately two to three scholars each year for a 5-year training period (Lo et al., 2023; Schust, 2024). During the first 2–3 years, scholars receive intensive basic science training at a research laboratory while under the supervision of experienced mentors. Scholars then spend an additional 2 years establishing their research programs as early-career faculty in an OB/GYN department, with 75 percent of their time in the laboratory as they return to their sponsoring clinical department duties (Lo et al., 2023; NICHD, 2023a). In 2023, the program

___________________

6 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Bayer HealthCare, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, National Cancer Institute, Ovarian Cancer Research Fund, Inc., and Society for Gynecologic Investigation (NICHD, 2023a).

was reduced from 100 percent protected time during the first 2–3 years and 75 percent for the remainder of the program to 75 percent in both phases (Lo et al., 2023). The overall training program was reduced from 5 to 4 years (Schust, 2024).

The program receives an annual budget of $770,000 a year for seven scholars, with enough funding to cover the salaries of two new scholars for 4 out of 5 years and only one new scholar using NIH funds in 1 of the 4 years of the grant (Schust, 2024). Although the RSDP award states that the scholars will receive $25,000 per year for supplies and travel, no NIH funds in the grant are available to cover these costs (Lo et al., 2023; Schust, 2024). RSDP is meant to be a stepping-stone for a successful career as a physician-scientist and provides a salary and fringe support, research supply costs, protected research time, the ability work with accomplished researchers in biomedical research, potential collaborations for future projects, and continuous scientific and career support (Lo et al., 2023; Schust, 2024).

A 2023 study on RSDP provides data on scholars’ academic achievements (Lo et al., 2023).7 Seventy percent have remained active in academia and span from instructor (4 percent), assistant professor (19 percent), associate professor (21 percent), to full professor (25 percent), with many in leadership roles—academic director (32 percent), medical director (10 percent), department chair or vice chair (15 percent), and dean or associate dean or vice dean (3 percent). The study found that RSDP’s unique two-phase structure has affected scholars’ career development and highlights how programs like this are critical for maintaining a well-trained workforce of OB/GYN scientists, especially in light of that workforce diminishing and underinvestment in WHR (Lo et al., 2023). For example, compared to K08 and K23 recipients from other medical specialties, and OB/GYN K08 and K23 recipients, RSDP scholars had similar R01 success rates. In addition, the 8-year conversion time from RSDP K12 to an R01 was comparable to published rates for K08 and K23 (6 and 7 years, respectively) (Lo et al., 2023).

The Effect of NICHD K Awards

In addition to the program successes described, several authors have studied the success of K award programs. One group evaluated the outcomes for NICHD career development and training grant awardees from 1999 to 2001 and reported that M.D.s with individual K awards were more successful at achieving independent funding compared to those with institutional K12 support. M.D.s/Ph.D.s had no significant difference in subsequent funding whether they had an individual or institution career

___________________

7 A 30-item survey was used to assess the demographics and career details of all current and former RSDP scholars.

development award (Twombly et al., 2018). Both the individual K and institutional K12 awards led to successful development of a cohort of research, with 75.2 percent who remained in academic medicine.

Another group also reported on recipients who received K08, K12, and K23 awards from 1988 to 2015 (Okeigwe et al., 2017). Their findings demonstrated that OB/GYN physician-scientists who received mentored early-career development K programs had a higher likelihood of receiving NIH independent research funding compared to nonrecipients. This study identified 388 K award recipients, including 66 percent women and 82 percent M.D.s. Over 80 percent were K12 awards, while 10 percent and 8 percent were K08 and K23, respectively, with 22 percent succeeding at obtaining an R01 between 1988 and 2009. There did not appear to be significant differences in sex, educational degree, or subspecialty and successful independent funding (Okeigwe et al., 2017).

These studies, along with those discussed regarding the BIRCWH, WRHR, and RSDP programs collectively, reveal the importance of NIH K awards in training a WHR workforce. While individual K awards may lead to higher success in NIH funding, the value of institutional K12 awards indicated high retention of the workforce in academia. NIH could improve these and similar K awards by increasing the duration of appointments to allow flexibility in effort, such as providing more protected time for bench and translational research and clinical and health services research. See later in this chapter for additional opportunities to address barriers to becoming a clinician-researcher.

Other Programs and Awards

Specialized Centers of Research Excellence (SCORE) on Sex Differences

SCORE programs focus on identifying the role of biological sex differences on women’s health through research at multifaceted levels. SCORE is the sole NIH Center program dedicated to disease-agnostic research on sex differences (NIH, 2024h). It is a U54 grant mechanism managed by ORWH and a significant initiative aimed at understanding the role of biological sex differences in health outcomes. It serves as a national resource for translational research and promotes integrating sex as a biological variable in biomedical research. It is not limited to specific diseases but rather focuses broadly on sex differences across conditions affecting women (ORWH, n.d.-c).

SCORE was established in 2018, but before that, the Specialized Centers of Research P50 program funded scientists making contributions to sex differences research related to women’s health from 2002 to 2017 (NIH, n.d.-w). SCORE established 12 new Centers: Los Angeles, CA (2 Centers), Denver,

CO, Rochester, MN, Atlanta, GA, Augusta, GA, Charleston, SC, Baltimore, MD, New Haven, CT, and Boston, MA (3 Centers), with investigators studying varied topics, such as aging, cardiovascular disease, influenza, microbiome, fatty liver, inflammation, and stress (ORWH, n.d.-c).8 Each SCORE Center receives $1.5 million a year in funding (NIH, 2022e).

The program implemented SCORE’s Career Enhancement Core to train the next generation of sex difference researchers. It consists of financial resources for early-career and senior faculty, educational curricula for graduate and medical students, standards for researching sex differences, and state-of-the-art research methodologies, along with pilot projects and complementary training programs (HHS, 2018). Each SCORE Center acts as a national hub for research on sex and gender, facilitating collaboration among researchers from academia, private industry, and federal settings. This collaborative environment enhances the program’s ability to address complex scientific questions.

The program has led to significant contributions in the field of sex differences research, influencing the development of new medical interventions and improving health outcomes for women (ORWH, n.d.-c). In 2023, the Journal of Women’s Health published a special issue highlighting the program’s work. The studies found that it has significantly advanced the field’s understanding of how sex differences affect health and disease and highlighted how biological, physiological, and behavioral differences between men and women influence the prevalence, progression, and treatment outcomes of various diseases. The research has employed innovative methodologies to better capture and analyze sex differences, including nuanced experimental designs and analytical techniques that account for gender-specific variables (Agarwal et al., 2023; Bennett et al., 2023; Reue and Arnold, 2023).

SCORE programs allow for studying women’s health and sex differences with more focus on individual research areas and for projects to mature to the point they are ready for R01 or equivalent funding. They also provide a community of researchers and trainees within the programs who come together and share their science annually. Their challenge is that they tend to be limited to a research focus that has funding support by individual ICs. Therefore, SCORE programs, like many program project grants, need individual IC support and buy-in while the application is being developed; if it receives a good score, it will be funded. It is likely that many investigators do not know this, limiting the SCORE grants on sex differences and

___________________

8 Augusta University, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Emory University, Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Mayo Clinic, Medical University of South Carolina, University of California, Los Angeles, University of Colorado, and Yale University have SCORE programs.

women’s health to the ICs that want to fund the applications. At this time, few ICs participate in the funding,9 which constrains the breadth and depth of the research.

R35 Grants

Most programs and grant mechanisms described have focused on early- and midcareer researchers. R35s are one mechanism designed to better support more senior investigators. “The purpose is to promote scientific productivity and innovation by providing long-term support and increased flexibility to experienced [PIs]” and those “whose outstanding record of research demonstrate their ability to make major contributions” to the particular IC’s mission (NIH, 2024d). The R35 is intended to support a research program, rather than a research project, by providing the primary source—and most likely the sole source—of funding for an investigator receiving an individual grant award (NIH, 2024d). The advantage over standard R01 grants is the amount and duration. For example, a standard R01 can be funded up to $500,00010 in direct costs per year without asking permission from the IC. However, these grants are for 5 years at most. In contrast, the R35 provides up to $750,000 per year in direct costs for up to 7 years (length varies by IC), allowing investigators more freedom to perform experiments that might be hypothesis generating and conduct follow-up studies based on data generated in prior research.11 Only select ICs offer R35s.

Recently, Congress mandated greater funding for Type 1 diabetes research to make breakthroughs in both the biology and treatments to improve the outcomes of this chronic debilitating disease (NIDDK, 2024). The investigators have been allotted $250 million annually. This mechanism could be used as a model to catalyze women’s health and sex differences research and allow for rapid discoveries at both the laboratory and the clinic in areas that desperately need funding and attention. Research funded by such a mechanism could, for example, study the changes in activity levels controlled by estrogen in the hypothalamus that may reduce dementia in women. The R35 mechanism could also be used to provide foundation funding for interdisciplinary groups that study the biology and treatments of endometriosis. Since R35s provide 7 years of continuous funding,

___________________

9 The following ICs support one or more SCORE programs: NIA (6 centers), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1 center), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1 center), National Institute on Drug Abuse (1 center), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI; 2 centers), and NIMH (1 center) (NIH, n.d.-w).

10 See, for example, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/grants-and-training/policies-and-guidelines/applications-with-direct-costs-of-500000-or-more-in-any-one-year (accessed October 22, 2024).

11 See, for example, https://www.aamc.org/news/nih-funds-more-long-term-grants (accessed October 22, 2024).

investigators can take the time needed to study the underlying mechanisms in depth and translate the findings to the clinic.

A senior NIH-funded investigator can obtain funding for their grants for up to 5 years via other grant mechanisms. Grant renewal efforts need to start after 3 years of funding to allow time for peer review. In addition, only about 20 percent of all R grants are funded (Lauer, 2024), making it a competitive climate. For these reasons, it often takes approximately 3 years for a senior investigator to obtain funding for a new R01 grant. A 7-year grant would allow them to make foundational observations, publish their work, and inform clinicians about both the biology of and best treatments for ailments that affect women or have sex differences in presentation or outcomes. In summary, IC support of R35 grants for specific investigators who are experienced and can undertake research to address important women’s health questions could be an effective mechanism to increase and support those studying women’s health and sex differences and make significant breakthroughs.

Reentry and Retention of Women’s Health Researchers

A large number of trained women’s health and sex differences researchers, particularly those who are female, need to leave their field or scale back research because of other demands, both career and external, that prevent them from finishing current projects (NASEM, 2024c). This includes pregnancy and the number and timing of children as a particular point of inflection in women’s careers in submitting applications and funding applications. These factors prevent them from being competitive for peer-reviewed funding from NIH or other peer-reviewed grant applications. Lack of policies that support informal caregiving and eldercare also have a negative effect on the physician workforce conducting WHR. A recent study found that among midcareer, full-time medical school faculty aged 55+, 22 percent of women and 17 percent of men were caregivers, and 90 percent of them were experiencing mental or emotional strain from those responsibilities (Skarupski et al., 2021). In another study, women faculty were 2.5 times more likely to be caregivers than men, as were older compared to younger faculty (Rennels et al., 2024). Among physicians who were mothers, those with additional informal caregiving responsibilities experience more burnout and mental health concerns than those without (Yank et al., 2019). Without investment in policies, programs, and resources to support women faculty engaged in informal caregiving, women academicians in WHR and clinical care delivery are at risk of leaving the workforce, further impeding progress in women’s health equity. Data on researchers who leave the workforce due to caregiving responsibilities and on reentry are important to collect to assess impact on the careers of the NIH intra- and extramural workforce.

To encourage researchers to re-enter the workforce, ORWH put out a Notice of Special Interest (NOSI) in 2023 titled Research Supplements to Promote Reentry and Reintegration into Health-Related Research Careers (NOT-OD-23–170). The Reentry Supplements Program was established in 1992, and since 2012, 24 ICs have participated in this career development program for full- or part-time research. The program has three components: reentry supplements, reintegration, and retraining and retooling. Designed to enhance existing research skills and knowledge in preparation for grantees to apply for a fellowship (F), career development (K) award, a research grant (R), or another type of independent research support, these programs allow administrative supplements to be given to existing NIH research grants for researchers to continue their work after leaving the workforce for family care responsibilities12 or if they were affected by hostile work environments. The program is also open to those who want to broaden their skill set (ORWH, n.d.-b). Twenty-four ICs have participated, with the NCI and National Institute of General Medical Sciences being the most active (ORWH, n.d.-b).

The reentry program provides mentored research training for at least 1 year. A researcher needs to have at least 6 months of career interruptions arising from qualifying circumstances, such as family responsibilities, and a doctorate or equivalent degree. Some ICs also consider predoctoral students or those enrolled in dual-degree programs (ORWH, n.d.-b). The reintegration program is for pre- and postdoctoral students who have experienced unlawful harassment and helps them find a new work environment that is safe and supportive. The retraining and retooling program, which provides up to $90,000 per year in salary support and $50,000 per year in program-related expenses, is aimed at early- or midcareer researchers and provides new environments to expand skill sets while continuing to support their parent grant; the aim is cross-sectional collaboration and interdisciplinary partnerships to prepare and successfully apply for independent research funding.13 According to ORWH, 80 percent of the awardees have been women, with 61 percent of applicants receiving awards (ORWH, n.d.-b).

Recommendations from a 2024 National Academies Report

In 2024, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released the report Supporting Family Caregivers in STEMM: A Call to Action (NASEM, 2024c). It describes how the labor and contributions of caregivers are often invisible and undervalued, with a specific focus on the academic science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine

___________________

12 Childrearing is the most cited reason for hiatus among applicants.

13 See https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-23-170.html (accessed August 11, 2024).

(STEMM) ecosystem, including undergraduate and graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, resident physicians and other trainees, tenure-track and non-tenure-track faculty, staff, and researchers. That report made several important recommendations to federal agencies for improvement (see Box 8-1), so this committee focused its recommendations on other areas to improve the women’s health and sex differences research workforce.

BOX 8-1

Relevant Recommendations from the 2024 report Supporting Family Caregivers in STEMM: A Call to Action

- Allow and support flexibility in the timing of grant eligibility as well as grant application and delivery deadlines for those with caregiving responsibilities and provide support for coverage while a grantee is on caregiving leave (e.g., decrease and streamline the paperwork and approval processes for grant applications).

- Allow no-cost grant extensions based on caregiving needs.

- Provide flexibility in eligibility timelines when an investigator has taken caregiving leave, such as eligibility deadlines for early-career scholars.

- Consider caregiving leave and acute caregiving demands as valid reasons for acceptance of a late application along the same timelines as other late applications.

- Introduce and allow grant supplements or the redistribution of funding within a grant budget to support coverage for someone to continue scholarly work while the grantee is on caregiving leave.

- Facilitate the leave and reentry processes for those who take a caregiving leave (e.g., provide research supplements to promote reentry following a period of caregiving leave; make supplements available to all types of caregivers, not solely parents; and cover costs associated with restarting a laboratory or research program as well as professional retraining).

- Fund innovative research on family caregiving in academic STEMM by providing competitive grants to institutions to support pilot projects and develop policy innovations.

- Congress should enact legislation to mandate a minimum of 12 weeks of paid, comprehensive caregiving leave. This leave should cover various contexts of caregiving, including childcare, older adult care, spousal care, dependent adult care, extended family care, end-of-life care, and bereavement care.

SOURCE: NASEM, 2024c.

Additional Workforce Support from ORWH

To address in part the inadequate representation of women in biomedical research, the NIH ORWH Working Group on Women in Biomedical Careers released two NOSIs in December 2022 that aim to retain early-career researchers. One, Administrative Supplements to Promote Research Continuity and Retention of NIH Mentored Career Development (K) Award Recipients and Scholars (NOT-OD-23-031), supports individuals with K awards during their shift from a mentored career development to independent research. The second, Administrative Supplement for Continuity of Biomedical and Behavioral Research Among First-Time Recipients of NIH Research Project Grant Awards, aims to improve the retention of first-time recipients of NIH research project grant awards who are experiencing a critical life event, including high-risk pregnancy, childbirth, adoption, serious personal health issues, or primary caregiving responsibilities for an ailing child, partner, parent, or immediate family (NOT-OD-23-032). During FY 2020 and 2021, the first 2 years of the program, data showed 87 percent of awardees were women and 10 percent were men. The racial breakdown of the participants was 60 percent White, 23 percent Asian, 6 percent African American or Black, and 5 percent more than one race (6 percent did not report). The most common reason for requesting the supplement was childbirth (77 percent) (NIH, n.d.-l).

ORWH is also involved in other mentored career development programs in partnership with ICs, such as the Team Science Leadership Scholars Program launched in 2022 with the NIAMS as a pilot with $2.5 million from ORWH. The program aims to fund four to five applicants with 20–50 percent protected time.

Loan Repayment Programs (LRPs)

Congress established NIH LRPs “to recruit and retain highly qualified health professionals into biomedical or biobehavioral research careers.” The programs are designed to address increasing costs of education that are causing scientists to leave research (NIH, n.d.-e). They offer applicants up to $50,000 annually to repay qualified educational debt in return for their commitment to engage in NIH mission-relevant research (NIH, n.d.-e). Specifically, awardees are required to conduct “qualifying research supported by a domestic nonprofit or U. S. government (federal, state, or local) entity” for at least 20 hours per week over a 2-year period (NIH, n.d.-h). There are several basic eligibility requirements, including holding an advanced degree, having qualifying educational debt, conducting qualifying research that represents 50 percent or more of total level of effort, and being a U.S. citizen (NIH, n.d.-h).

The LRPs are available to both researchers not employed by NIH (extramural) and those employed by the agency (intramural) under one of the following subcategories (NIH, n.d.-c):

- “Clinical Research: Patient-oriented and conducted with humans.

- Pediatric Research: Directly related to diseases, disorders, and other conditions in children.

- Health Disparities Research: Focuses on minority and other health disparity populations.

- Research in Emerging Areas Critical to Human Health: For researchers pursuing major opportunities or gaps in emerging areas of human health.

- Clinical Research for Individuals from Disadvantaged Backgrounds: Available to clinical investigators from disadvantaged backgrounds.

- Contraception and Infertility Research: On conditions affecting the ability to conceive and bear young.”

LRP awards are intended to support and build a scientist’s research career rather than fund research related to these specific topics. New LRP awards are typically offered for 2 years. Repayments for a new award are calculated using the eligible educational debt at the start of the contract (NIH, n.d.-f). Renewal award applicants must have eligible debt of at least $2,000 to apply (NIH, n.d.-f). Payments are made quarterly, starting with the highest-priority loan, with no limit on the number of renewal awards someone can receive. Until their debt is repaid, successful renewal award applicants may continue to apply for, and potentially receive, competitive renewal awards (NIH, n.d.-f).

Each IC convenes external peer reviewers to assess applications to identify those most closely aligned with the IC’s mission and priorities. Criteria include the potential to pursue a career in research and the quality of the overall research environment (NIH, n.d.-h).

Extramural LRP Awards and Success Rates

Between 2011 and 2023, $991,946,952 was awarded through the extramural LRP; 33,611 LRP applications were received (new and renewals), with 17,584 awarded—a success rate of 52 percent. The mean award was $56,412 (NIH, n.d.-n). During this same period, 20,270 new applications were received, with 8,460 of these awarded—a success rate of 42 percent. The mean award was $72,079. There were also 13,341 renewal applications; 9,124 of these were awarded, with a success rate of 68 percent. The mean renewal award was $41,885 (NIH, n.d.-n).

While success rates for applications have steadily increased, from 50 percent to 69 percent between 2011 and 2023, applications overall have declined from 3,159 in 2011 to 1,906 in 2023 for reasons that are unclear but could be related to fewer researchers staying in academia (Rothenberg, 2024; Wosen, 2023). Total funding for the program, however, has grown from $72 million in 2011 to $93 million in 2023 (NIH, n.d.-n).

Table 8-3 includes LRP grant success rates by race for all, new, and renewal awards in 2011 and 2023. Success rates have generally increased among all races. Among all awards, Black/African American success rates increased the most (from 37 to 67 percent); however, they continued to lag slightly behind White, Asian, and Other applicants (70, 69, and 68 percent, respectively). This trend is also noted among success rates for new awards,

TABLE 8-3 Loan Repayment Program Grant Success Rates for All, New, and Renewal Awards by Race

| Success Rate (All Awards) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2023 | |

| Race of Applicants | ||

| Asian | 52% | 69% |

| Black/African American | 37% | 67% |

| White | 52% | 70% |

| Other | 49% | 68% |

| Success Rate (New Awards) | ||

| 2011 | 2023 | |

| Race of Applicants | ||

| Asian | 43% | 63% |

| Black/African American | 30% | 57% |

| White | 39% | 62% |

| Other | 41% | 59% |

| Success Rate (Renewal Awards) | ||

| 2011 | 2023 | |

| Race of Applicants | ||

| Asian | 68% | 77% |

| Black/African American | 50% | 83% |

| White | 70% | 82% |

| Other | 64% | 83% |

SOURCE: Data from NIH, n.d.-g.

while Black/African American and Other race applicants have the highest success rates (83 percent) for renewal awards (see Table 8-3).

In 2023, LRP funding varied significantly by IC, with NHLBI providing $15.67 million, NCI $13.97 million, NICHD $7.53 million, and NIAID $7.41 million being the largest funders by dollar amount (not percentage); the NIH OD, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and National Library of Medicine provide some of the lowest levels at $144,023, $183,694, and $313,818 respectively. NICHD and the OD allocate a higher percentage of their total budgets to LRP, though they have smaller budgets (NIH, n.d.-i).

Intramural LRP Awards and Success Rates

Within the intramural LRP, the overall success rate has increased between 2015 and 2023, while the number of applications and awards has fallen. In 2015, 82 applications were received and 69 funded, for an 84 percent success rate. In 2023, 68 applications were received and 63 funded, for a 93 percent success rate (NIH, n.d.-k).

Regarding funding and awards by IC, in 2023, NCI, NIAID, and NIMH provided the most funding, with NIH Clinical Center and National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) funding the least (see Table 8-4) (NIH, n.d.-k).

Table 8-4 Intramural Loan Repayment Program Awards By Institutes and Centers in 2023

| IC | Awards | Funding |

|---|---|---|

| CC | 1 | $92,580 |

| NCI | 9 | $1,374,374 |

| NHGRI | 1 | $92,580 |

| NIAID | 5 | $651,962 |

| NICHD | 2 | $185,160 |

| NIDCR | 1 | $231,450 |

| NIMH | 5 | $511,946 |

| NINDS | 2 | $266,943 |

| Total | 26 | $3,406,995 |

NOTE: CC = Clinical Center; NCI = National Cancer Institute; NHGRI = National Human Genome Research Institute; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NICHD = Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDCR = National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; NIMH = National Institute of Mental Health; NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

SOURCE: Data from NIH, n.d.-k.

NIH LRP Evaluations

Evaluations of the LRP program have been conducted, with varying results, though several studies have noted that it has been helpful in retaining researchers and increasing their productivity. A 2009 evaluation of the extramural LRP noted that it has been effective in recruiting and retaining its physician doctorate target population overall, but has not as effectively retained women Ph.D.s, stating that “the LRPs are selectively losing women awardees.” The report further noted it “would be appropriate to examine program design and retention in more detail to determine how the LRP can better serve women PhDs” (National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Program Evaluation Working Group, 2009). It also commented the LRPs are attracting more African American and Black applicants compared to the demographics of recent M.D. and Ph.D. graduating classes, with no racial or ethnic differences in success rate (National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Program Evaluation Working Group, 2009).

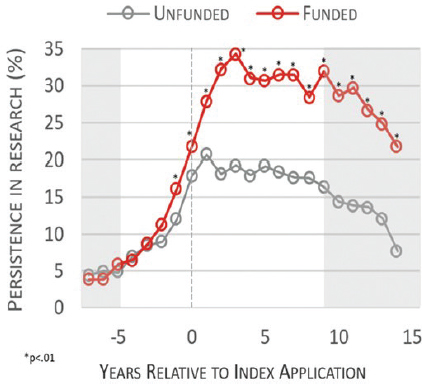

Another evaluation examined research productivity among LRP participants followed for 10 years after receiving an award between 2003 and 2009 (Lauer, 2019). Results indicated that awardees demonstrated consistently higher levels of “persistence in research,” defined as submitting grant or fellowship applications, receiving grant or fellowship awards, and publications (see Figure 8-9). Over time, LRP-funded individuals demonstrated an approximate twofold increase in research productivity, compared to those who did not receive awards, a difference that continued at 14 years after their LRP application (Lauer, 2019).

SOURCE: Lauer, 2019.

In a survey of 1,938 LRP awardees, nearly all discussed benefiting professionally and personally from participating in the program, citing ability to pursue research goals, reduced clinical duties, and added confidence in their research career (Lauer, 2019). Another evaluation followed two cohorts of NHLBI LRP applicants who received awards in 2003 and 2008 over a 10-year period; obtaining the LRP award was strongly associated with increased submission of and success in obtaining grant funding and publications. Furthermore, “the LRP award appears to enhance retention in the biomedical research workforce when measured using metrics of grant application and award rates as well as research publications over a 10-year period” (Kalantari et al., 2021). Similarly, in a 2005 assessment of the intramural LRP, participation was associated with higher rates of both NIH and research retention, including in HIV/AIDS-related and clinical research (Glazerman and Seftor, 2005).

Student Loans and Early-Career Salaries in Academia

The burden of student loans differs significantly between women and men, with women generally facing a heavier financial load. This disparity is influenced by several factors, including the amount of debt taken on, repayment periods, and wage gaps.

Women hold approximately 64 percent of all U.S. student loan debt, totaling some $929 billion (Education Data Initiative, n.d.-b). On average, women graduate with $3,120 more (an average debt of $22,000 compared to $18,880 for men) (AAUW, n.d.-b). Men are less likely to take out loans, though parents of White male students are more likely to take out loans on their behalf or pay out of pocket than they are for female students. This difference in debt is exacerbated by disparities in salaries after graduation, with women earning between 26 and 81 percent of what their male counterparts do, making repayment more challenging (AAUW, n.d.-a; Education Data Initiative, n.d.-b). For women of color, the wage gap is even more pronounced, with Black women earning 64 cents and Latinas earning 51 cents for every dollar paid to White, non-Hispanic men (National Partnership for Women and Families, 2024).

Women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields, including scientists, face unique challenges. Women are more likely to pursue advanced degrees, which increases their overall student debt, and women in these fields often earn less than their male counterparts. This disparity can exacerbate the financial strain of repaying student loans and deter women from pursuing lengthy and costly training programs required for physician-scientist roles (Fry et al., 2021; Hardy et al., 2021). The average debt for medical school alone is approximately $202,453 (Education Data Initiative, n.d.-a).

Having fewer women scientists contributes to gaps in knowledge about women’s health, as women are more likely to study relevant diseases and conditions. For example, a study that analyzed the sex of PIs for cardiovascular clinical trials found that only 18 percent were led by women, but those enrolled more female participants (Yong et al., 2023). Furthermore, a study of 1.5 million papers in the medical literature found that studies authored by women were more likely to include gender and sex analysis (Nielsen et al., 2017). Another study analyzed biomedical research articles from 2002 to 2020; women were more likely to study topics that benefit women (Koning et al., 2021). That study also reviewed biomedical patents and found that female research teams are 35 percent more likely to create treatments for women’s conditions than male teams.

Importantly for WHR, 85 percent of OB/GYN medical residents are female (Vassar, 2015). Women are less likely to stay in academic medicine and more at risk of not independently obtaining grants because of the barriers discussed in this chapter. Since OB/GYNs are more likely to conduct research on related topics, failing to support OB/GYN physician-scientist development will continue to widen the gaps in WHR related to these conditions.

LRPs Summary

Women scientists and women’s health researchers in general are essential to grow the WHR portfolio at NIH. However, early-career investigators with potential to study women’s health and sex differences have a substantial debt burden from training, leading them to exit research because of the need for higher salaries and lack of steady funding to support them as they apply for grants at the start of their career. The LRP program, by relieving debt, might enhance their ability to stay on the research and physician-scientist path. Since women earn less money in research and academic positions, LRP may be an even greater and more urgent need for them. If the goal is to increase such research, retaining and supporting the workforce is key.

OVERVIEW OF THE NIH PROGRAM AND INTRAMURAL WORKFORCE

As of September 2023, the NIH workforce was 19,595 staff (including administrative) working in a wide range of positions in ICOs throughout the agency; over 60 percent were female. The racial and ethnic breakdown of the workforce is as follows (NIH, n.d.-q).

- 5.1 percent (1,006) identify as Hispanic or Latino.

- 51.5 percent (10,097) identify as White.

- 20.6 percent (4,031) identify as Black or African American.

- 20.6 percent (4,027) identify as Asian.

- 0.1 percent (21) identify as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

- 0.7 percent (134) identify as American Indian or Alaska Native.

- 1.4 percent (279) identify as two or more race groups.

The following section summarizes the workforce of Offices with a role in grantmaking or other responsibilities relevant to WHR, such as portfolio analysis. However, because limited information is publicly available detailing the composition of the intramural workforce by function and IC, the committee was constrained in its ability to characterize it. Data on specific expertise related to women’s health or sex differences were not readily available.

Center for Scientific Review (CSR)

CSR is the primary Center that assesses grant applications for scientific merit. It organizes peer review groups and study sections to evaluate them. CSR’s mission is to ensure that all grant applications receive “fair, independent, expert, and timely scientific reviews—free from inappropriate influences” (CSR, 2022). See Chapter 3 for more information.

According to FY 2023 data, 476 staff worked at CSR, with 61.6 percent (293) females and 38.4 percent (183) males (NIH, n.d.-p). As of 2021, Black and Hispanic individuals accounted for only 18.7 and 6.5 percent of CSR staff, respectively, indicating a lack of diversity among those evaluating grant applications (NIH, n.d.-q). These staff are experts who work with the external reviewers (CSR, 2022). Each CSR scientific division has six scientific review branches, including specific groups with key staff supporting those reviews (CSR, 2022). Staff have expertise in a large range of areas, corresponding to the ICs they support (CSR, 2022). Women’s health and sex differences are not listed among the areas of expertise on the CSR website, although individuals within the listed categories could have such expertise.

Given the lack of focus on WHR in general at NIH, staff with expertise in this area may be inadequate. Moreover, if there is an influx of grants on women’s health and sex differences research, such as in response to the recommendations of this report (see Chapter 9), the insufficiency will be exacerbated.

ORWH

ORWH has almost 30 staff members with a diverse range of professional and scientific expertise in areas to support and advance the consideration of women’s health and sex and gender influences across the entire research continuum to improve women’s health (NIH, n.d.-x). Staff

have expertise in autoimmune ocular diseases, the role of sex and gender in health and disease, gender and women’s studies, community-led HIV research, reproductive justice, applied developmental psychology, children’s development, sex and gender differences in autoimmune diseases, orthopedics, obstetrics, gynecologic oncology, obesity, diabetes, aging, and community-based epidemiology, among many others (NIH, n.d.-x).

Division of Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives (DPCPSI)

“DPCPSI plans and coordinates trans-NIH initiatives and research supported by the NIH Common Fund, and develops resources to support portfolio analyses” (NIH, n.d.-o). Twenty staff with a wide range of expertise support the division in the main office and over 500 staff makeup the offices within DPCPSI, including those with backgrounds in biochemistry, biophysics, health science policy, substance use disorder, bioethics, and nutrition, among others (NIH, 2024c, n.d.-o).

DPCPSI’s Office of Portfolio Analysis has 34 staff with a wide range of expertise, including molecular biology, systems biology, chemical engineering, computer science, machine learning, electrical engineering, science policy, chemistry, toxicology, biomedical science, molecular genetics, epidemiology, international science policy, data analytics and data science, bioinformatics, and neuroscience (NIH, n.d.-s).

OD’s Office of Extramural Research (OER)