Research on the Dynamics of Climate and the Macroeconomy: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 5 Past and Contemporary Lessons in Macroeconomic Shocks and Risks

5

Past and Contemporary Lessons in Macroeconomic Shocks and Risks

This session was designed to probe the sources of nonlinear, cascading, and compounding macroeconomic risk through a series of recent historical examples. The aim was to draw out specific lessons about the nature and mechanisms of macroeconomic risk that are potentially relevant to climate-related risk (interpreted as both physical and transition risks). The panelists were Laurence Ball (John Hopkins University), Markus Brunnermeier (Princeton University), Vellore Arthi (University of California, Irvine), and Joseph Tainter (Utah State University). The presentations provided a multifaceted understanding of macroeconomic risks, and the speakers highlighted the importance of proactive and flexible policy responses, studying past events to inform current strategies to mitigate the effects of climate change, and strategic investments in resilience and innovation.

PERSISTENT EFFECTS OF RECESSIONS

Laurence Ball discussed the long-term effects of macroeconomic shocks on the economy, such as financial crises, monetary policy tightening, and pandemics. Although mainstream macroeconomic theory suggests these shocks of transitory effects, leading to temporary recessions followed by a return to the long-run trend, an alternative view called “hysteresis” proposes that recessions can leave lasting scars on the economy. Hysteresis,1 a

___________________

1 “Hysteresis in the field of economics refers to an event in the economy that persists even after the factors that led to that event have been removed or otherwise run their course” (Investopedia.com).

term borrowed from physics, implies that the impact of recessions extends beyond the short term, leading to persistent reductions in output and higher unemployment rates.

Ball outlined potential channels through which this occurs, including the long-term effects on unemployed workers, reduced investment in physical capital during recessions, and potential disruptions to technological progress and new firm formation. Despite hysteresis not being fully understood, Ball noted that empirical evidence suggests that recessions can have lasting effects on aggregate employment and output levels, as seen in the aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession, where output failed to fully recover to its prerecession trend.

Despite these challenges, Ball suggested that appropriate macroeconomic policies can help mitigate or reverse the long-term damage caused by recessions. He said that expansionary fiscal or monetary policies can help stimulate the economy and counter some of the long-term damage caused by shocks, a concept he refers to as “reverse hysteresis.” He highlighted the rapid recovery after the 1980s U.S. recession, attributed to aggressive monetary policy. He contrasted this with the slower recovery after the 2008 Great Recession (Ball, 2014), emphasizing the importance of effective policy responses.

Finally, Ball briefly discussed the COVID-19 pandemic, noting that the strong fiscal response might have contributed to a quicker recovery compared to the 2008 recession. He highlighted macroeconomists’ understanding of how macroeconomic shocks can cause long-term impacts on the economy and the potential for appropriate policy responses to mitigate these impacts. However, he acknowledged that the relevance of these insights to the effects of climate change remains a topic for further exploration.

MACRO AND CLIMATE RISKS: A RESILIENCE PERSPECTIVE

Markus Brunnermeier contrasted different approaches for understanding and addressing shocks, especially in the context of climate change and other complex systems. A risk approach is framed in terms of probabilities and quantifying impacts, and a resilience approach is more dynamic, focusing on the ability to rebound from shocks through agile responses. Ex-ante2 agility enhancing investments can improve resistance. In contrast, a robustness approach aims to avert the worst outcomes via rigid rules.

Brunnermeier elaborated on the concept of resilience by drawing an analogy between an oak tree (rigid yet vulnerable) and a reed (flexible yet resilient) facing hurricane winds. He discussed resilience barriers, such as

___________________

2 The term “ex-ante” describes future events that are based on forecasts rather than real-world outcomes (https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/exante.asp).

traps, where systems can become entrenched and struggle to recover (hysteresis). He highlights that tipping points are even worse than traps, as they trigger feedback loops that induce the system to escalate out of control. Brunnermeier noted that tipping points in climate change were identified as critical threats.

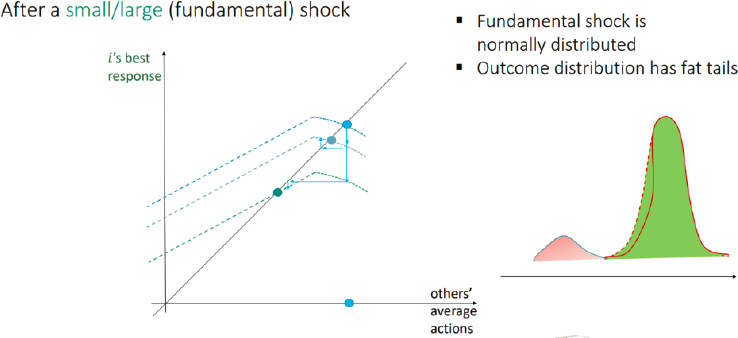

Emphasizing the importance of understanding feedback loops, particularly adverse ones and spillover effects, Brunnermeier explored strategic complementarities and substitutes in reaction to externalities, highlighting their role in either amplifying or stabilizing shocks. Systems can react to shocks as either stabilizing (shock absorber) or exacerbating (shock amplifier) the situation. He discussed risk metrics such as co-value at risk (CoVaR) and nonlinearities, connecting them to fat tails in probability distributions (see Figure 5-1). Furthermore, he suggested that resilience depends significantly on the speed of change, comparing sequences of small shocks to one large shock.

When asked about the challenges posed by irreversible shocks and strategies for addressing them, Brunnermeier emphasized the importance of distinguishing between risk shocks from which recovery is possible and those that are irreversible, requiring proactive measures. He suggested that resilience can be built by preparing for recoverable shocks and acting swiftly against irreversible ones. He was also asked about the idea of extending resilience into a transformative framework, considering long-term changes beyond incremental responses. He highlighted that resilience depends on the speed of transition. Slow transition can be positive, but fast transition can lead to adverse movements, ultimately hitting a tipping point that destroys resilience. For example, in the green transition, rapid transitions may incur

SOURCE: Presented by Markus Brunnermeier on November 2, 2023.

high costs, whereas a gradual approach allows for a natural replacement of capital stock, albeit at a slower pace.

Brunnermeier underscored the complexity of understanding and managing risks, resilience, and robustness amid uncertainties, particularly in the context of climate change and systemic dynamics.

USING A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE TO STUDY SHOCKS

Vellore Arthi examined the relationship between climate/environment, macroeconomy, and human populations, with an emphasis on the value of historical perspectives for studying the consequences of environmental or macroeconomic shocks on human welfare. Arthi outlined some of the specific advantages of a historical approach:

- Diverse natural experiments: Historical data offer a variety of environmental and macroeconomic incidents, providing diverse natural experiments to study.

- Longer timescale: History provides a longer timescale, crucial for studying phenomena with long-term effects, such as climate change, intergenerational wealth transmission, and human capital development over the life course.

- Rich data: Historical data are extensive, enabling the study of impact to human populations with detailed, linkable microdata often unavailable in modern settings due to privacy concerns.

Arthi illustrated these advantages with three examples from her research:

- Dust bowl exposure: By studying cohorts exposed to the Dust Bowl during childhood, Arthi examined the long-term effects of compounding exposures on health and labor market outcomes. The results indicated a significant impact of exposure in early childhood, emphasizing the importance of early interventions (Arthi, 2018).

- Great Depression’s impact on career trajectories: Using longitudinal cohort studies, Arthi and her collaborators investigated how cohorts experiencing the Great Depression in their early careers fared later. Contrary to expectations, highly impacted cohorts did as well or better than those less impacted, with macroeconomic shocks accelerating sectoral and occupational changes (Arthi et al., 2023).

- Health effects of recessions with migration responses: Arthi and her collaborators explored the health effects of a recession in

- Britain caused by the U.S. Civil War. Correctly estimating results amid unobserved migration revealed that it negatively impacted health—contrary to both the procyclical findings typical in the broader recession-mortality literature and results in this same setting produced by standard methods that implicitly ignore migratory responses. These divergent results highlight the importance of accounting for migratory responses to macroeconomic conditions (Arthi et al., 2022).

In each example, Arthi demonstrated how the historical approach allows for a better understanding of adaptive responses and can enable researchers to overcome particular challenges in estimating the impact of macroeconomic shocks on human populations. Although Arthi acknowledged the vastly different socioeconomic and environmental contexts of modern settings, she noted that historical and some modern contexts share similarities, such as low levels of baseline income and health and weak social safety nets. She emphasized that the diversity in historical episodes can help identify relevant factors for modern challenges. By studying historical examples, Arthi suggested, researchers can gather evidence on which mechanisms are relevant in a particular setting and apply this knowledge to contemporary issues, even without direct data. She concluded by emphasizing the need for nuanced analysis in understanding the complex interplay between climate, macroeconomy, and human welfare.

COMPLEXITY IN THE MACROECONOMY

Joseph Tainter discussed the changing landscape of innovation and its impact on society’s ability to tackle complex challenges, such as climate change. Despite a long-standing belief in innovation as a solution for societal problems, Tainter argued that the nature of scientific research is evolving, with growing complexity and costliness potentially shifting research into diminishing returns. He noted that innovation has evolved from the era of individual geniuses to large interdisciplinary teams. He suggested that this shift toward complexity can have a significant cost. Tainter illustrated this with examples such as Moore’s Law, which describes the exponential growth in computing power over time. Tainter pointed out that although Moore’s Law has fueled technological advancements, sustaining this growth requires exponentially more researchers and resources, leading to a decline in research productivity.

To support his claim, Tainter discussed his research (with Deborah Strumsky and José Lobo) analyzing data from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office encompassing over 5 million patents worldwide. His findings revealed that although innovation has become more complex, the productiv-

ity of research (patents per author) is declining with larger patenting teams (Strumsky et al., 2010). He asserted that this reduction in productivity is likely to continue due to the growing complexity of research questions.

Tainter connected these trends in research productivity to their potential impact on society’s ability to address climate change. As research becomes more resource intensive and yields diminishing returns, he noted a risk that appropriators, such as government funders, may be less inclined to support lines of research with decreasing productivity. This could have significant implications for initiatives aimed at mitigating and adapting to climate change, potentially hindering progress in finding effective solutions.

Tainter concluded by questioning the assumption that innovation will continue to solve complex societal problems, highlighting the escalating costs and declining productivity in research, which could impact society’s ability to address challenges, such as climate change.

DISCUSSION

The open discussion began with a question about whether to intensify or abandon innovation efforts, particularly for complex issues, such as climate change. Tainter suggested that the answer depends on the government’s policy priorities and future vision. A participant asked about the impact of the energy transition on employment compared to the pace of innovation. Ball answered that economists’ primary focus on innovation and technological progress is the role in economic growth rather than job creation. Brunnermeier added that transitioning to clean energy may produce more employment opportunities as more green investment is needed.

Another participant suggested focusing on social governance innovation rather than technological innovation to address climate change. Tainter suggested that this might require government attention to both technical and societal aspects as issues become more complex. Brunnermeier noted that large shocks, such as those caused by climate change, can shift social norms and governance issues.

A participant asked if the dynamics of shock absorbers or amplifiers are influenced by the underlying network structure. Brunnermeier explained that all shocks propagate through the network, and the extent of interconnections in the network affects the magnitude of spillovers. He mentioned both physical and “virtual” connections (where entities are not directly linked but are exposed to similar shocks, leading to coordinated reactions). He emphasized that reactions are intensified when networks are closely linked, which can exacerbate situations.

A participant raised the question of learning from historical events to better prepare for the future. Ball noted that significant shocks have driven the economy toward equilibrium (i.e., the Great Depression and Social

Security, World War II [WWII] and women in the labor force). However, he acknowledged that not all instances align with this pattern. Brunnermeier emphasized that shocks can have both positive and negative impacts on the economy, but the ability to envision new outcomes and draw lessons from history are crucial for decision making. Without leveraging historical insights, prediction becomes more challenging, especially during transition phases, such as the Great Depression and WWII. Arthi underscored the importance of understanding history in responding promptly to major shocks, citing the 1918 influenza pandemic and COVID-19. Data from the 1918 pandemic informed early efforts to determine the human capital damage posed by COVID-19. Data from both the 1918 pandemic and COVID-19 may enable quicker responses in the future. Arthi also highlighted the cost-effectiveness of using historical data compared to devising responses from scratch to mitigate shocks.

A participant inquired about the impact of climate change on business responses and the potential for positive feedback loops. Tainter suggested that the innovation of new products could generate numerous investment opportunities and foster competition in business. Ball highlighted that climate change introduces new risks to the economy that could trigger financial crises and economic recessions. Brunnermeier raised the issue of tipping points, noting that many climate risks evolve slowly until a sudden collapse occurs. He pointed out that although tipping points already exist in the financial sector, the effects may not be immediately apparent until the climate reaches a critical tipping point.

Another participant asked how to measure the net benefits of innovation amid rising costs. Tainter offered an example from the military sector, where he observed diminishing returns due to increasing complexity, illustrated by the reduced production of advanced weapons, such as bombers. However, he acknowledged his limited exploration of the commercial sector and its broader complexities. Ball suggested that the decline in patents may indicate not necessarily a decrease in innovation but rather an improvement in patent quality. Tainter posited that the commercial sector could determine the net benefit of innovation by gains in market shares. Brunnermeier highlighted that innovation might be increasing in some sectors (e.g., green technology) and decreasing in others. He proposed that innovation levels might also be rising within these expanding sectors. Tainter countered by stating that his research across various sectors, including newer ones, such as nanotechnology and biotechnology, revealed a decline in innovation trends, spanning both old and emerging sectors, such as pharmaceutical and chemical.

A participant raised a question about using microlevel data and causal inference to inform larger-scale modeling, especially regarding the impact of major shocks on long-term productivity. Arthi highlighted the difficulty

of scaling up such estimates and the importance of producing a diverse range of estimates using various methods to better understand contextual features. For example, she highlighted the differences in effects and mechanisms between localized industrial shocks and large macroeconomic recessions, suggesting that more evidence and context could help provide a basis for empirical choices that are better conceptually justified.

Another participant asked Ball about whether hysteresis is observed solely in economic growth rate or also in levels. Ball noted that most economic examples can be looked at in terms of levels, citing the 2008 Global Recession as an example. He explained that some of the more affected countries, such as Spain and Greece, experienced a decline in growth levels, leading to widening gaps with less affected nations. However, he noted that hysteresis is typically discussed primarily in terms of its effect on levels.

Addressing the slowdown in the rate of innovation, a participant speculated on whether climate change might be a contributing factor, as research efforts shift to address it. Tainter considered this a value judgment that can only be fully understood in the future, as society determines which research areas are most critical in addressing climate change. Brunnermeier highlighted how climate change affects global public goods, which tend to lack investments as well as innovation. He suggested that shifting innovation on combating climate change could lead to a collective effort that fosters rather than hinders innovation.