Research on the Dynamics of Climate and the Macroeconomy: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 3 Nonlinear, Cascading, and Compounding Risks in the Economy

3

Nonlinear, Cascading, and Compounding Risks in the Economy

Karen Fisher-Vanden opened the next session with an overview, delving into the propagation mechanisms of systemic risk across sectors, regions, and time. The panel discussions spanned experts who consider micro-behavioral responses to risks cascading through the economy to those who consider risks cascading through the macroeconomy in an attempt to bridge the micro- and macrolevels and find linkages between the two. These experts included Catherine Hausman (University of Michigan), Etienne Espagne (World Bank), Stephie Fried (Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco), Yongyang Cai (The Ohio State University), and Matthew Kahn (University of Southern California). Some speakers discussed the economic implications of individual decision making and individual exposure to climate risks, with one highlighting the importance of considering both aggregate and individual risks. Additionally, some discussed the risks associated with the transition to cleaner energy sources and noted the importance of understanding market and distributional impacts. Several modeling approaches and opportunities were discussed. One speaker called for models capable of capturing self-reinforcing processes and negative feedback loops within the energy transition, and another emphasized the value of integrated modeling frameworks to understand regional challenges.

OVERVIEW

Karen Fisher-Vanden provided an overview of the methodology her research team employs to understand the propagation of risks across diverse systems. They approach the complex, interconnected nature of

risks in the context of climate change by asking fundamental scientific questions. Specifically, they explore questions concerning the spatial and temporal resolutions within subsystem models, crucial feedback mechanisms between different systems, and nuanced propagation of risks and uncertainties across interconnected networks. Fisher-Vanden emphasized the importance of considering overlapping and interacting networks of natural and human systems with distinct spatial and temporal variability, where specific patterns can converge to create impacts. For example, power system blackouts can occur from the convergence of high temperatures from the atmospheric system, low water levels from the hydrologic system, a higher demand for electricity, and reduced power generation due to lack of water for thermal cooling.

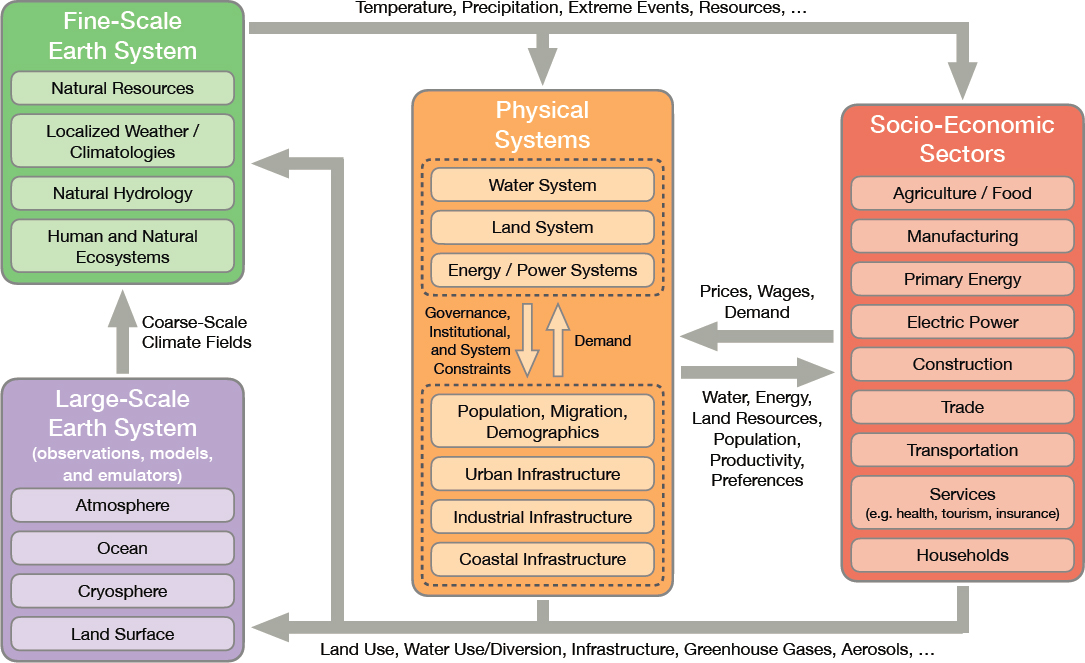

Through their involvement with the Program on Coupled Human and Earth Systems (PCHES) Project,1 Fisher-Vanden and her team aim to develop integrated modeling tools capable of addressing a wide array of challenges, including cascading and compound stressors, multiscale dynamics, and adaptive responses. Fisher-Vanden presented their model, which integrates comprehensive Earth systems data with sophisticated physical models of energy, water, and land dynamics (see Figure 3-1). This holistic approach considers various socioeconomic factors, including population dynamics, demographic shifts, and infrastructural development.

Illustrating their approach with tangible examples, Fisher-Vanden elucidated the intricate interplay between natural and human systems through two studies. Webster et al. (2022) examined the effects of high temperatures and water scarcity on the power system. They integrated fine-scale Earth system data into a coupled water-power-economy model, representing interconnected networks including the atmosphere, watersheds, power grid, and regional economy. By overlaying temperature and precipitation data onto the watershed network at daily and grid-cell levels and adding layers for the power grid (hourly) and regional economy (annual and state levels), they traced how external shocks propagate through these networks.

Fisher-Vanden explained that the study found that water and power networks intersect where generators draw water for cooling and use it for hydropower. The electricity transmission network transfers energy from generators to demand centers, which economic sectors, such as manufacturing, use to produce goods and services for consumption. Using high temperature and water scarcity, Webster et al. (2022) modeled how an external

___________________

1 The PCHES Project is a university-based, integrated research team supported by the Department of Energy’s MultiSector Dynamics program. The project is highly collaborative and works in interdisciplinary teams; the goal is to create new, state-of-the-art integrated modeling tools to capture the complex dynamics, including cascading and compounding stressors in interdependent systems, multiscale and multisector dynamics, and risk and response behaviors. For more information, see https://www.pches.psu.edu/.

SOURCE: https://www.pches.psu.edu/frame.

shock is transformed and transported throughout the interconnected networks, which dampen or amplify its impacts. Fisher-Vanden explained that without fine-scale analysis, predicting these impacts is challenging. The study showed water shortages leading to generator shutdowns, causing outages and congestion on transmission lines in unexpected locations. Despite adverse effects on economic sectors and consumption due to outages and higher electricity prices, feedback loops involving responses to market changes can help mitigate overall economic impacts (Webster et al., 2022).

In Fan et al. (2018), Fisher-Vanden and her collaborators investigated climate-induced migration and its regional economic impacts. They used an econometric residential sorting model with a regional economy-wide model to analyze population changes under different climate scenarios. Fisher-Vanden explained that, although research often stops at predicting migration patterns, this study considered how migration impacts wages and housing prices. By integrating these factors, they achieved a more nuanced understanding of the potential outcomes. The results showed that although climate-induced migration initially led to an increase in population movement northward, the endogenization of wages and housing prices significantly mitigated this trend (Fan et al., 2018; see Table 3-1). Fisher-Vanden explained that migration could dampen wages and increase housing prices, which may mitigate further migration. The study also examined regional economic impacts, including changes in gross regional product and per capita income (see Table 3-2).

Fisher-Vanden concluded with three key takeaways. First, she emphasized the importance of capturing interactions across scales for impacts and adaptation. She explained how considerations such as location, timing, and duration can significantly influence outcomes, as demonstrated by the macroeconomic implications of power shortages or household location choices. Second, she stressed the importance of capturing interactions and feedbacks within and between systems. She reiterated that feedback loops involving demand, wages, and price can dampen or amplify impacts, emphasizing the importance of their inclusion in modeling efforts. Last, she noted the significance of accounting for compound risks and uncertainty across networks. Fisher-Vanden said that a response to risk in one network can propagate to affect others, underscoring the benefit of capturing these complexities for more accurate assessments.

COMMUNICATION AND INDIVIDUAL DECISION MAKING

Matthew Kahn highlighted the multifaceted challenges presented by climate change and adaptation strategies and their implications for household decision making. He discussed ongoing research conducted in partnership with Redfin and First Street Foundation, aimed at bridging the gap between

TABLE 3-1 Regional population shares (%) in 2065

| Regions | Census 2010 | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | Scenario 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast | 18.70 | 12.48 | 15.68 | 15.05 | 21.37 | 16.42 |

| Midwest | 20.77 | 14.10 | 19.70 | 21.33 | 21.51 | 20.35 |

| South | 39.13 | 46.23 | 40.36 | 41.53 | 34.64 | 38.18 |

| West | 8.84 | 13.72 | 9.73 | 8.78 | 9.17 | 10.07 |

| California | 12.56 | 13.47 | 14.52 | 13.31 | 13.30 | 14.98 |

| Climate-induced migration | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Endogenous wages | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Endogenous housing price | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

NOTES: The Census 2010 column shows population shares obtained from the U.S. census for the base year 2010 that were incorporated into the computable general equilibrium (CGE) model. The Scenario 1 column shows population shares in 2065 from CGE Scenario 1, where population growth is assumed to follow census population projections. The Scenario 2 column shows population shares after iterating between the random utility model (RUM) and CGE model to achieve consistency in regional population shares and regional wage rates. The Scenario 3 column shows results from iterating between the RUM and CGE models to achieve consistency between both wage rates and housing prices. The Scenario 4 column presents baseline climate-change scenario results based on Fan et al. (2018, Eq. 11), which does not endogenize wages and housing prices. The Scenario 5 column shows population shares with endogenous wages and housing prices incorporating climate change–induced migration generated by the RUM.

SOURCE: Adapted from Fan et al. (2018). Permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

TABLE 3-2 Regional economic impacts from climate-induced migration in 2065 (%)

| Regions | Population | GRP | Consumption | Per Capita Income | Net Exports | Welfare |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast | 9.11 | 6.57 | 6.37 | –2.86 | 6.80 | 6.05 |

| Midwest | –4.58 | –3.14 | –3.14 | 1.50 | –4.63 | –3.16 |

| South | –8.07 | –5.55 | –5.49 | 2.97 | –7.58 | –5.38 |

| West | 14.67 | 10.41 | 9.95 | –4.28 | 8.42 | 9.43 |

| California | 12.52 | 8.69 | 8.23 | –4.28 | 8.42 | 7.78 |

| United States | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.09 |

NOTES: The table reports the percentage in gross regional product (GRP), consumption, per capita income, net exports, and welfare between Scenario 5 (climate change–induced migration after endogenizing wages and housing prices) and Scenario 3 in 2065. The results show that in regions with a decline (increase) in population, a decrease (increase) in GRP and consumption is observed because of a reduction (increase) in demand for goods and services. Net exports are lower (higher) in these regions because of the reduced (increased) output. The welfare impacts are positive in the Northeast, West, and California but negative in the South and Midwest.

SOURCE: Adapted from Fan et al. (2018). Permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

complex climate science and actionable information for individuals. It involved integrating climate science into real estate platforms, such as Redfin, to inform individual homebuyers.

First Street Foundation developed a 10-point scale to rate flood risk, providing a tangible way to communicate risk severity associated with different geographic areas. In a randomized experiment on Redfin, millions of U.S. people searching for housing were divided into treatment and control groups. The treatment group received information about flood risk without being aware of their participation in an experiment. This real-world setting allowed researchers to observe how individuals respond to climate risk information when making housing decisions.

Kahn highlighted a pattern from the study’s findings: individuals searching for homes in high-flood-risk areas tended to adjust their preferences and opted for safer properties upon learning about the risks, but those searching in low-risk areas did not. Furthermore, Kahn noted that the flood score treatment information was equally effective for those searching in counties that voted for Donald Trump and those that voted for Joe Biden in 2020, which suggests that private efforts to adapt to new risks that one is informed about is not influenced by political ideology. Ultimately, he highlighted the potential for climate science to drive individual behavioral changes and adaptation strategies.

ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Catherine Hausman discussed the complexities surrounding the energy transition and the potential risks it poses to both the macroeconomy and individual actors within it. She began by highlighting her focus on energy markets, noting their significance as one of the primary contributors to climate change and the potential for policy makers to intervene in their regulatory authority over these markets. Hausman identified three key reasons that the energy transition and associated policies may introduce risks. First, she argued that energy markets already suffer from inherent inefficiencies and failures, diverging from the idealized economic model of perfectly efficient markets devoid of regulatory or market failures. She explained that these imperfections become more prominent and are exacerbated during the transition to cleaner energy sources and when exposed to physical climate risks. Hausman noted the extensive economic scholarly engagement with these issues, exemplified by studies on topics such as fossil fuel subsidies (e.g., Parry et al., 2021), transmission policy (e.g., Davis et al., 2023), methane (e.g., Hausman and Raimi, 2019), and misaligned incentives (e.g., Blonz, 2023).

Second, Hausman emphasized the unequal distribution of the transition’s impacts on households, underscoring existing societal disparities

and incomplete safety nets (Dorsey and Wolfson, 2024). She highlighted how policies designed to foster cleaner practices in energy markets may disproportionately affect specific households. For example, Davis and Hausman (2022) explored how natural gas utility firms navigate the recovery of their capital costs within a specific legal and regulatory framework, considering the energy transition’s implications for shareholders, customers, and households reliant on utilities such as natural gas for heating.

Last, Hausman highlighted how energy policy for a cleaner transition will likely involve substantially redistributing risks among various stakeholders. She predicted that this may lead to incumbent energy firms seeking to protect their interests, potentially resorting to lobbying and other tactics to influence policy decisions. She also warned of potential conflicts and threats to democratic processes. She emphasized the benefit of further research in this domain.

Overall, Hausman emphasized the necessity of regulation in navigating the risks inherent in the energy transition. Acknowledging the importance of regulatory interventions, she also underscored the importance of careful design to mitigate unintended consequences and ensure the protection of vulnerable populations amid these transformations in the energy landscape.

Etienne Espagne explained the concept of a “midtransition” in the context of climate change and its cross-border dimensions. Grubert and Hastings-Simon (2022) define the midtransition as a phase characterized by the coexistence of emerging zero-carbon and fossil fuel systems, each imposing constraints on the other. Espagne underscored the potential length of this phase if not managed properly, highlighting the benefit of policies and instruments aimed at minimizing its duration and ensuring smooth progression of the energy transition across social, economic, and financial domains (Espagne et al., 2023).

Espagne noted that the midtransition will inevitably have some instability (Mercure et al., 2021). For example, he highlighted the potential for supply–demand mismatches in energy production because of the coexistence of two conflicting systems (Mercure et al., 2021), which can lead to volatility in energy prices and supply disruptions. Espagne also emphasized the coordination problems that may arise, especially in declining industries (Espagne and Magacho, 2022). These industries, often reliant on fossil fuels, face the challenge of managing their decline while ensuring a smooth transition for workers and communities dependent on them. Failure to address these coordination issues could exacerbate social and economic tensions, hindering the overall transition process. Moreover, Espagne discussed the risk of stranded assets (investments in fossil fuel infrastructure that may become economically unviable in a low-carbon future). He explained that this poses challenges for both energy companies and countries heavily reliant on fossil fuel exports for revenue and economic stability. Stranded assets

can influence countries’ positions on climate action, energy security, and geopolitical relations, adding another layer of complexity to the transition (Mercure et al., 2021).

Espagne argued that midtransition is a cross-border problem. He explained that different countries play distinct roles in the global energy landscape, with some being major fossil fuel exporters and others exporting clean energy technologies. His work at the World Bank endeavors to distill the complexity of cross-border risks during this phase by introducing country archetypes, elucidating their interactions via trade, social dynamics, and financial mechanisms.

Espagne expressed a need for macroeconomic models capable of encapsulating diverse self-reinforcing processes and negative feedback loops. For example, the energy transition involves self-reinforcing processes—cost reductions and increased deployments reinforce each other (Mercure et al., 2021; Nijsse et al., 2022; Way et al., 2022). However, he noted that there may be reverse processes, such as bottlenecks in the supply chain and constraints on critical minerals for low-carbon technologies (Boer et al., 2021; Lapeyronie and Espagne, 2023; Miller et al., 2023). Addressing the financial aspects, Espagne discussed the World Bank’s support for interventions in the green financial sector, acknowledging potential ramifications on macroeconomic stability, particularly for fossil fuel–exporting nations reliant on technology imports (Donnelly et al., 2023; Monasterolo et al., 2022).

During the open discussion, Kemp-Benedict asked about the necessity of studying transition risks solely from a global perspective, prompting Espagne to underscore the importance of capturing cross-border dynamics within country-specific macroeconomic models. He suggested that overlooking the cross-border dimension can lead to a misunderstanding of country dynamics that may misinform adaptation and mitigation strategies.

ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF PHYSICAL CLIMATE RISKS

Stephie Fried presented on the physical risk of climate change, highlighting both aggregate and idiosyncratic components of risk. She explained that the former involves uncertainties in the total amount of climate damage, such as damages associated with sea level rise or the change in frequency and severity of storms. The latter refers to uncertainties in the damage experienced by individual households or firms. Despite much attention on the aggregate risk (e.g., Cai and Lontzek, 2019; Bakkensen and Barrage, 2019; Lemoine, 2021; Lemoine and Trager, 2016; van den Bremer and van der Ploeg, 2021), Fried emphasized the importance of considering idiosyncratic risk, which is less studied but also important. Using storms as an example, she explained how only some households may be affected, and climate change can alter the distribution of these idiosyncratic shocks.

Fried compared two approaches to modeling climate damage from storms. The first assumes perfect insurance where every household experiences the average damage. This approach is commonly used in the integrated assessment literature, which uses aggregate damage functions. The second approach incorporates idiosyncratic risk, acknowledging that only some households may be affected. Her findings revealed significant differences in adaptation investment (e.g., reinforcing roofs, building stilts) between the two approaches, with investment being 80 percent lower under the aggregate approach. This is due to homeowners being risk averse and therefore more likely to invest in adaptation due to high idiosyncratic risk (Fried, 2022).

Moreover, Fried stressed the importance of considering both aggregate and idiosyncratic risks to understand how households and firms respond to climate change and the implications for the macroeconomy. Despite the limited study of idiosyncratic risk in the climate literature, she suggested leveraging insights from macroeconomic tools (e.g., Bewley–Huggett–Aiyagari models [Aiyagari, 1994; Huggett, 1993; Imrohoruglu, 1989]) to explore its implications further.

During the discussion, Fried addressed a question regarding the correlation between storm shocks and existing inequities. She emphasized the importance of considering adaptive capacity within the model, noting that it is endogenous. This means that people of different income levels adapt differently. Fried illustrated this point by discussing how individuals with low incomes who have stretched their resources to afford a home are particularly vulnerable to storm-related shocks due to limited resources for adaptation. The discussion highlighted the nuanced relationship between income levels, homeownership, and vulnerability to climate impacts in the modeling framework.

INTEGRATED REGIONAL ECONOMIC MODELING

Yongyang Cai discussed two projects: Dynamics Integration of Regional Economy and Spatial Climate under Uncertainty (DIRESCU) and Dynamic Regional Integrated Framework of Food, Energy, and Water Systems (DRFEWS).

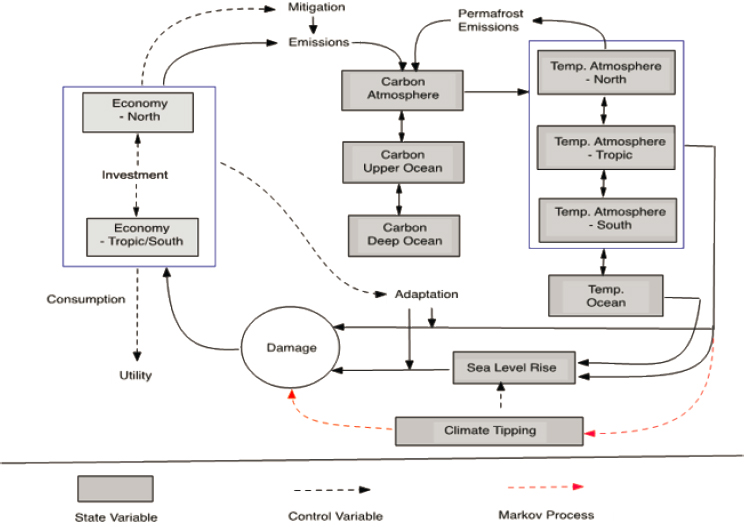

DIRESCU considers factors such as economic activity, carbon emissions, temperature variations, and climate tipping points, dividing regions into northern and tropics/southern areas to reflect economic and climatic disparities (see Figure 3-2). Cai emphasized the model’s inclusion of a Markov chain to simulate irreversible damages from climate tipping points, suggesting a comprehensive approach to inform policy formulation. Using DIRESCU to analyze policy scenarios, Cai found that developed regions have higher optimal carbon taxes than developing regions under both

cooperation and noncooperation scenarios. Additionally, he noted that climate tipping risks can significantly increase regional social cost of carbon (SCC) under either scenario, with noncooperation potentially resulting in lower carbon taxes.

DRFEWS integrates multiple models to assess sustainability, including dynamic regional, five-state CGE, a local land use, and farmer land decision models. By combining these models, researchers can analyze the impacts of global changes (e.g., climate change, carbon pricing) on local land use patterns, farmer decision-making processes, and regional ecosystem sustainability, Cai said. He underscored the importance of integrated modeling frameworks in understanding and addressing regional stability challenges through informed policy interventions.

DISCUSSION

During the open discussion, the panelists considered several unique aspects of climate economics as a discipline. Hausman and Cai noted its interdisciplinary nature, with Cai emphasizing its global dimension, which can require international cooperation that may add a political dimension. Hausman underscored the flexibility of climate economics in using various methodologies based on real-world questions. She stressed the importance of bridging the gap between environmental or climate economists and the broader economic community. Kahn discussed the challenge of dealing with a moving target in a nonstationary setting, highlighting the uncertainties and unknowns of climate change. Espagne agreed, suggesting that the traditional optimization models may not be suitable for this situation, where countries are not on track to reduce emissions. He suggested developing specific tools to address the structural change aspect of economies in the context of climate change. Last, Fisher-Vanden suggested incorporating climate into national accounts, proposing a green GDP that considers natural capital. This prompted a discussion on how accounting for climate in national economic models could change the baseline.

One participant asked each panelist to identify three research gaps that could advance the field of climate and economic modeling. Fisher-Vanden outlined the challenge of conducting uncertainty analysis in large coupled systems, emphasizing the importance of innovation to avoid oversimplifying models into emulators. Furthermore, she emphasized the need for data to improve understanding of institutional behavior and responses. Last, she underscored the importance of enhancing the interconnection of different models so they can inform each other, such as by incorporating the impacts of social costs of greenhouse gas emissions back into the macroeconomy.

Hausman emphasized the significance of ensuring that macroeconomic models can incorporate the latest microlevel insights, encouraging ongoing

SOURCE: Presented by Yongyang Cai on November 1, 2023.

dialogue between the micro- and macroeconomic research communities. Furthermore, she stressed the value of papers exploring the growth versus levels question, considering statistical and macroeconomic theoretical approaches to discern when climate change will affect levels versus growth and its implications for estimating the SCC. Last, she highlighted political economy questions as an area of interest, noting the benefits of considering endogenous firm behavior and the role of companies in shaping policies to comprehensively understand corporate influence on climate-related decisions.

Kahn emphasized the need for macroeconomic advancements on endogenous adaptation. He argued that a significant asymmetry exists in environmental economics, with more optimism regarding endogenous progress on decarbonization compared to adaptation efforts. He suggested collaboration with macroeconomists to address this gap and achieve symmetry in economic approaches to both mitigation and adaptation challenges.

Another participant inquired about the significance of integrating climate factors into baseline economic projections. Specifically, they asked

whether macroeconomists should construct a baseline explicitly considering the physical impacts of climate change and subsequent responses from households, firms, and policies. Both Fried and Cai expressed support for incorporating climate effects into baseline projections if they were likely to be relevant for the economic question. Fried discussed the challenges associated with incorporating various types of climate damage and suggested a targeted approach focusing on specific types, such as storm or heat damage. Although she acknowledged potential interactions between types of damage, she highlighted the importance of incremental progress in this direction. Similarly, Cai acknowledged computational difficulties, particularly in disaggregating damage within DIRESCU, suggesting that feasibility is contingent on controlling the level of disaggregation. He also noted the difficulty in estimating uncertainty for adaptation costs and damage levels.

Espagne suggested carefully considering when to use optimization models versus simulating possible futures based on real-world economic factors. He highlighted two potential research themes: addressing geoeconomic fragmentation in the low-carbon transition and integrating finance into macroeconomic models to understand the impetus behind financial flows, especially in emerging and developing economies. He also stressed the importance of representing the role of financial flows, including nonclimate finance, in driving economy dynamics.

Last, the panelists were asked to provide their thoughts on the main limitation of models that economists use to assess the macroeconomic impact of climate change. Kahn expressed uncertainty about the probabilities of fat-tail events,2 influenced by Weitzman (2011), and noted the challenge of understanding low-probability but severe events. Fisher-Vanden highlighted the difficulty in forecasting long-term outcomes due to uncertainties in future economies, technologies, adaptation strategies, and individual preferences. She emphasized the challenge of modeling far into the future and suggested that macroeconomic approaches could provide assistance. Last, Hausman acknowledged the diversity of macroeconomic models in use and recognized that different models possess distinct limitations.

___________________

2 A fat-tail event, or fat-tail distribution, is a statistical distribution with a higher probability of extreme outcomes than a normal or bell-shaped distribution. In other words, these are scenarios where rare but extreme events are more likely than would be predicted by a normal distribution.

This page intentionally left blank.