Research on the Dynamics of Climate and the Macroeconomy: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 2 Nonlinear, Cascading, and Compounding Risks in the Climate

2

Nonlinear, Cascading, and Compounding Risks in the Climate

The focus of the first day was to compare perspectives on nonlinear, cascading, and compounding risk to inform how climate science and macroeconomics may collectively increase the understanding of climate risk. The first session opened with an overview from David Armstrong McKay (University of Exeter) on the characteristics of weather/climate changes and variability, including temporal and spatial manifestations. Next, a group of experts discussed translating climate risks into impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability of coupled human-natural systems. These experts included Matthew Huber (Purdue University), Kristie Ebi (University of Washington), Elisabeth Gilmore (Carleton University), and Mikhail Chester (Arizona State University). The presentations included discussions on more sophisticated macroeconomic modeling driven by climate change scenarios, understanding complex risk interactions with an emphasis on vulnerable populations, and adapting infrastructure and governance to better cope with the impacts of climate change. Speakers discussed climate and social tipping points, with one suggesting that social tipping points are expected to precede climate tipping points. Additionally, a couple of speakers highlighted the complexity of societal responses to risk.

OVERVIEW

Evidence of Climate Change

Armstrong McKay provided an overview of the state of science on climate impacts, focusing on tipping points and their implications for

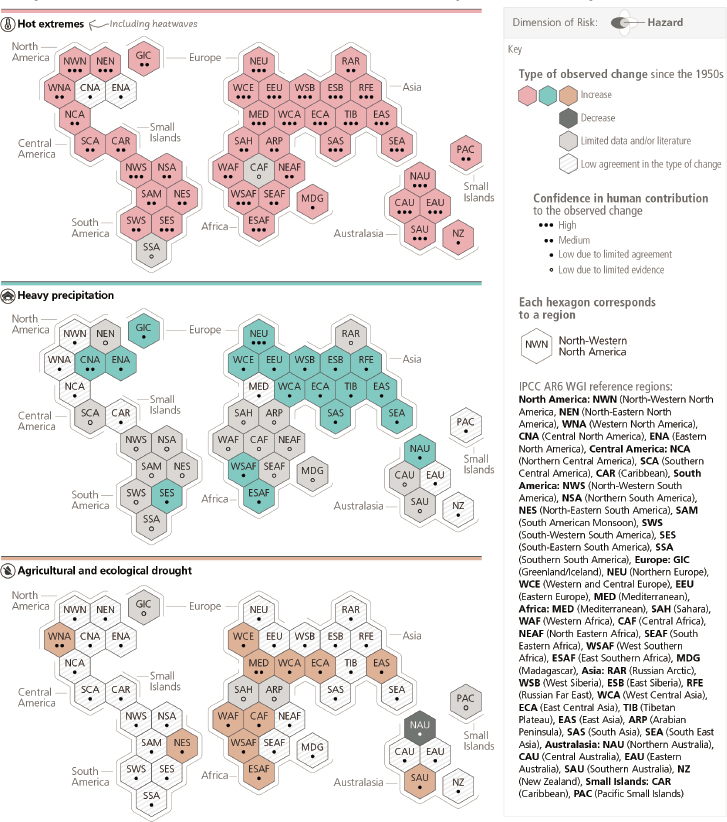

cascading risks. Drawing from the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report (IPCC, 2023), he presented evidence indicating increasing heat extremes, heavy precipitation, and agricultural and ecological droughts globally (see Figure 2-1). He noted the high confidence that heat extremes are increasing across all continents. There is also a clear pattern of increasing heavy precipitation events and agricultural and ecological droughts in many regions, particularly Eurasia and Africa.

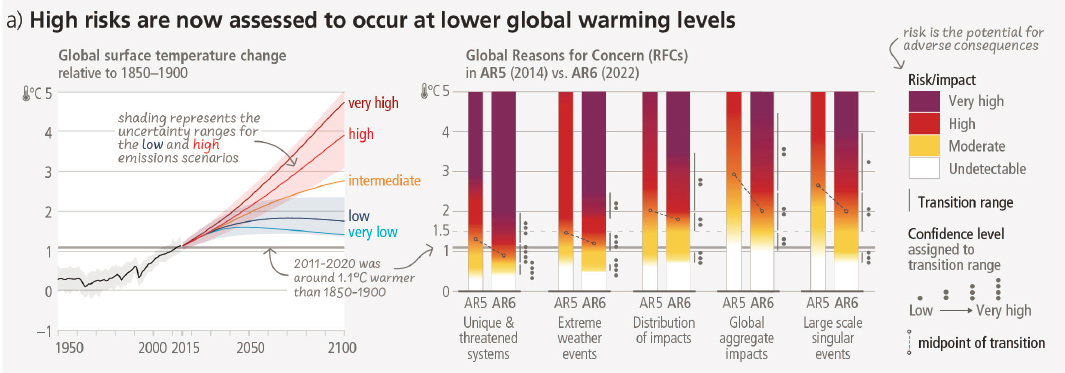

The IPCC (2023) report also underscored escalating impacts and risks with each incremental rise in global warming, illustrated graphically as “burning embers” (see Figure 2-2). Armstrong McKay noted that the global aggregate impacts are mostly concerned with economics, and many of the large-scale singular events are tipping points. Many regions are projected to face high and very high risks by 2°C and above, which Armstrong McKay said is reachable even in the low- to medium-emissions scenarios (see Figure 2-2).

Focusing on heat and humidity, Armstrong McKay highlighted findings by Lenton et al. (2023), revealing warming scenarios exposing more people to unprecedented heat, defined as a mean annual temperature ≥29°C. He emphasized that the current policy trajectory is projected to reach near 2.7°C warming by the end of the century (2080–2100), which would result in over 1 billion people (over 20 percent) living in extreme heat (Lenton et al., 2023). The most affected regions include the Amazon, West Africa, Sahel, Arabia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, where population densities are high. However, Armstrong McKay noted that in high-emissions scenarios, unprecedented heat exposure could affect billions of people.

Nonlinear and Tipping-Point Climate Risks

Armstrong McKay acknowledged that many climate impacts increase steadily with warming. Furthermore, he said that climate scientists expect many climate impacts to increase proportionally through warming; however, he noted that nonlinear changes may occur after surpassing certain thresholds. Drawing from the IPCC (2021) special report on 1.5°C, he showed through a figure the nonlinear escalation of risks associated with a 1.5 and 2°C increase in temperature (adapted in Table 2-1). For example, extreme heat exposure is 2.6 times worse at 2°C compared to 1.5°C, the loss of sea ice in the Arctic is 10-fold, and species loss doubles or triples with just a half-degree of additional warming. More differences are outlined in Table 2-1.

Next, Armstrong McKay focused on tipping points, which he defined as a change in a system that becomes self-sustaining once forced beyond a particular threshold. He cited the collapse of ice sheets as an example,

SOURCE: Figure 2.3 Panel (a) in IPCC (2023).

illustrating feedback loops amplifying melting. As the ice sheet surface melts, the top of the ice sheet lowers into lower, warmer altitudes, creating a self-reinforcing cycle with further melting and height loss. At a low enough elevation, even if global warming were halted, the ice sheet would continue melting because of this feedback process.

NOTES: Left: These changes were obtained by combining CMIP6 model simulations with observational constraints based on past simulated warming, as well as an updated assessment of equilibrium climate sensitivity. Very likely ranges are shown for the low and high greenhouse gas emissions scenarios (SSP1-2.6 and SSP3-7.0). Right: Diagrams are shown for each reason for concern, assuming low to no adaptation (i.e., adaptation is fragmented and localized and comprises incremental adjustments to existing practices). However, the transition to a very-high-risk level has an emphasis on irreversibility and adaptation limits. The horizontal line denotes the present global warming of 1.1°C which is used to separate the observed, past impacts below the line from the future projected risks above it. Lines connect the midpoints of the transition from moderate to high risk across AR5 and AR6.

SOURCE: Figure 3.3 Panel (a) in IPCC (2023).

TABLE 2-1 The differences between a +1.5°C and +2°C world

| 1.5°C | 2°C | 2°C Impacts | |

| Extreme Heat Global population exposed to severe heat at least once every 5 years |

14% | 37% | 2.6× worse |

| Sea-Ice-Free Arctic Number of ice-free summers |

At least 1 every 100 years | At least 1 every 10 years | 10× worse |

| Sea Level Rise Amount of sea level rise by 2100 |

0.40 m | 0.46 m | 0.06 m more |

| Species Loss: Vertebrates Vertebrates that lose at least half of their range |

4% | 8% | 2× worse |

| Species Loss: Plants Plants that lose at least half of their range |

8% | 16% | 2× worse |

| Species Loss: Insects Insects that lose at least half of their range |

6% | 18% | 3× worse |

| Ecosystems Amount of Earth’s land area where ecosystems will shift to a new biome |

7% | 13% | 1.86× worse |

| Permafrost Amount of Arctic permafrost that will thaw |

4.8 million km2 | 6.6 million km2 | 38% worse |

| Crop Yields Reduction in maize harvests in tropics |

3% | 7% | 2.3× worse |

| Coral Reefs Further decline in coral reefs |

70–90% | 99% | Up to 29% worse |

| Fisheries Decline in marine fisheries |

1.5 million tons | 3 million tons | 2× worse |

SOURCE: Adapted from WRI (2018) figure. WRI figure reformatted data from IPCC (2022).

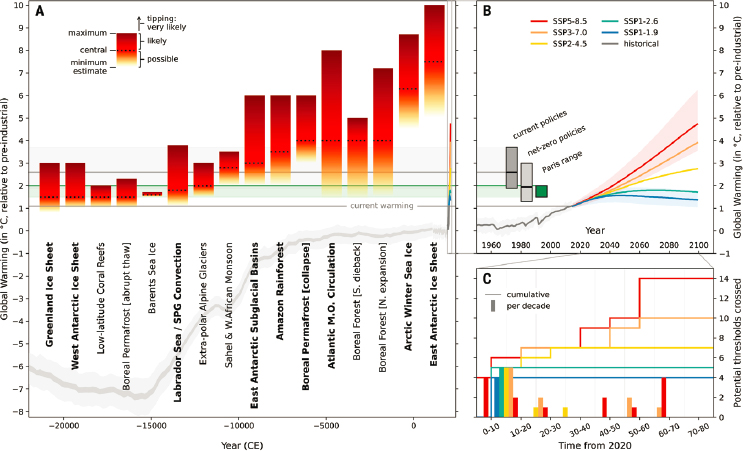

Moreover, he referenced a recent comprehensive reassessment of climate tipping points, which identified 16 elements and their potential tipping points (Armstrong McKay et al., 2022). These elements range from large-scale events, such as the collapse of ice sheets, to shifts in ocean currents and ecosystem disruptions, such as coral reef die-offs. Using the burning ember system from IPCC (2023), Armstong McKay et al. (2022) evaluated the likelihood of tipping points occurring across different systems (see Figure 2-3a). They found that the chance of passing a tipping point increases with warming up each burning ember, with tipping thresholds

NOTES: Bars in (A) show the minimum (base, yellow), central (line, red), and maximum (top, dark red) threshold estimates for each element (bold font, global core; regular font, regional impact), with a paleorecord of global mean surface temperature over the past ~25 ky and projections of future climate change from IPCC (2021) shown for context. Future projections are shown in more detail in (B) along with estimated 21st-century warming trajectories for current and net-zero policies (gray bars, extending into A; horizontal lines show central estimates, bar height the uncertainty ranges) as of November 2021 versus the Paris Agreement range of 1.5 to <2°C (green bar). The number of thresholds potentially passed in the coming decades depending on SSP trajectory in C is shown per decade (bars) and cumulatively (lines).

SOURCE: Armstrong McKay et al. (2022). Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

likely to be surpassed beyond the central estimate and tipping possible (but not yet likely) above the minimum estimate.

Armstrong McKay emphasized that current global warming trends are approaching several climate tipping-point thresholds, with some minimum estimates already exceeded, especially as temperatures approach and surpass 1.5°C above preindustrial levels. By the Paris Agreement range (1.5–2.0°C), four best-estimate tipping thresholds have been surpassed and have a higher likelihood of occurring. At 2.7°C of warming, multiple

climate tipping points have passed their likely levels. He said that despite mitigation efforts, lower-emissions scenarios may not prevent all tipping points from being crossed within the next few decades.

Addressing caveats, Armstrong McKay noted mixed confidence in estimates and emphasized the potential for interactions between tipping points. For example, he explained how the Greenland ice sheet collapse can trigger a cascade of events, such as disrupting the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), potentially leading to drying in the Amazon and increasing the risk of Antarctic ice sheet collapse (Wunderling et al., 2023).

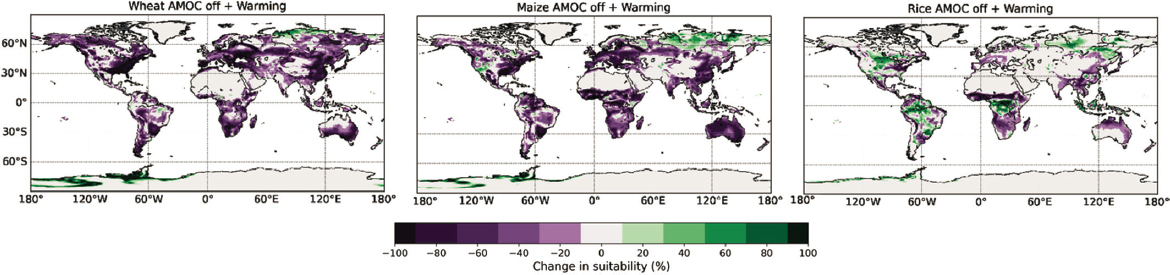

Differences Between Climate and Economic Modeling

Using the collapse of the AMOC as a case study, Armstrong McKay demonstrated the significant climate shifts that could occur, including cooling in the North Atlantic and warming in the Southern Hemisphere (OECD, 2021). Moreover, it could have substantial impacts on precipitation and agriculture, particularly in regions such as the Amazon, West Africa, South Asia, and Europe. OECD (2021) showed how these changes could substantially impact agriculture, with decreased global yields for wheat, maize, and rice (see Figure 2-4). Localized socioeconomic impacts could be seen with, for example, substantial cooling and drying in the United Kingdom, making arable agriculture economically unviable (Ritchie et al., 2020).

Although natural scientists anticipate net negative consequences of AMOC collapse, many economic models suggest a potentially positive impact (e.g., Anthoff et al., 2016; Diaz and Moore, 2017; Dietz et al., 2021), such as from temporarily reduced global warming. However, Armstrong McKay highlighted the complexity and nonlinearities involved, noting that economic models that assume a “smooth” damage function1 often overlook these factors, leading to underestimating their impacts. He suggested that incorporating tipping points into economic models could lead to a better understanding of their consequences, although attempts remain limited. Overall, he underscored the need for further research and interdisciplinary collaboration to address the uncertainties surrounding tipping points and their implications for society.

___________________

1 In some reduced-complexity economic models, a damage function represents the relationship between changes in climate variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation, sea level rise) and the economic impacts (Roson and Sartori, 2016). A “smooth” damage function exhibits a continuous and gradual change in economic impacts. In other words, it implies a linear or smoothly curving relationship between the level of climate change and its economic impact.

NOTES: The change in suitability is represented by a color spectrum from dark purple (–100 percent change) to dark green (+100 percent change). Land suitable for wheat and maize shows a significant loss. Although land suitable for rice crops increases slightly in some regions, this is offset by the land lost for wheat and maize crops.

SOURCE: OECD (2021).

MOIST HEAT STRESS AND HUMAN HEALTH AND PRODUCTIVITY IN MACROECONOMIC MODELS

Matthew Huber presented the implications of climate change within macroeconomic models. He highlighted the advantages of using sophisticated macroeconomic modeling approaches driven by climate change scenarios. Rather than relying on simplistic damage functions tied solely to temperature levels, these sophisticated models can offer granular, quantitative responses to climate change. However, Huber cautioned that this method applies only to specific types of shocks.

Huber shared some insights from his work examining moist heat stress (a combination of high temperature and humidity) and its effects on human health and productivity. He explained how it can significantly impact individuals engaged in outdoor labor, where the body’s ability to dissipate heat through sweating becomes less effective in high humidity. This can lead to decreased productivity and adverse health outcomes, particularly in labor-intensive sectors. He and other researchers apply these principles to labor functions that can be computed as a function of wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) (e.g., Kong and Huber, 2022).

To model the economic implications of moist heat stress, Huber and his colleagues integrated labor functions based on WBGT into the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) model.2 They employed these labor functions to evaluate the impact on outdoor labor in response to projected accumulated heat stress across different sectors over time, using scenarios from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project scaled by global mean surface temperature. Huber and his colleagues assessed the shock to labor capacity and its effects on GDP (see Figure 2-5). Their analysis revealed significant variations in labor capacity depending on the proportion of the workforce exposed to hotter, more humid conditions, which is not confined to outdoor labor. Their modeling approach can provide detailed, granular data, including insights into poverty changes in West Africa by country and strata. Huber’s modeling demonstrated substantial poverty shifts resulting from this one shock.

Moreover, Huber and his colleagues considered survivability thresholds (Vecellio et al., 2023), which indicate conditions under which it becomes difficult for individuals to work outdoors without protection. He highlighted the exponential nature of the relationship between global warming levels and socioeconomic consequences, underscoring the profound impact that each degree of warming could have on billions of people. He noted the importance of research to understand how to incorporate such detailed insights into macroeconomic models effectively.

___________________

NOTE: Labor capacity losses are relative to 1961–1990. Country-level labor capacity losses are constructed as weighted average of labor capacity losses across all 65 sectors and four labor types using employment shares from GTAP database version 10 as weights.

SOURCE: Saeed et al. (2022).

CLIMATE CHANGE RISKS, VULNERABILITY, AND SOCIETAL RESPONSES

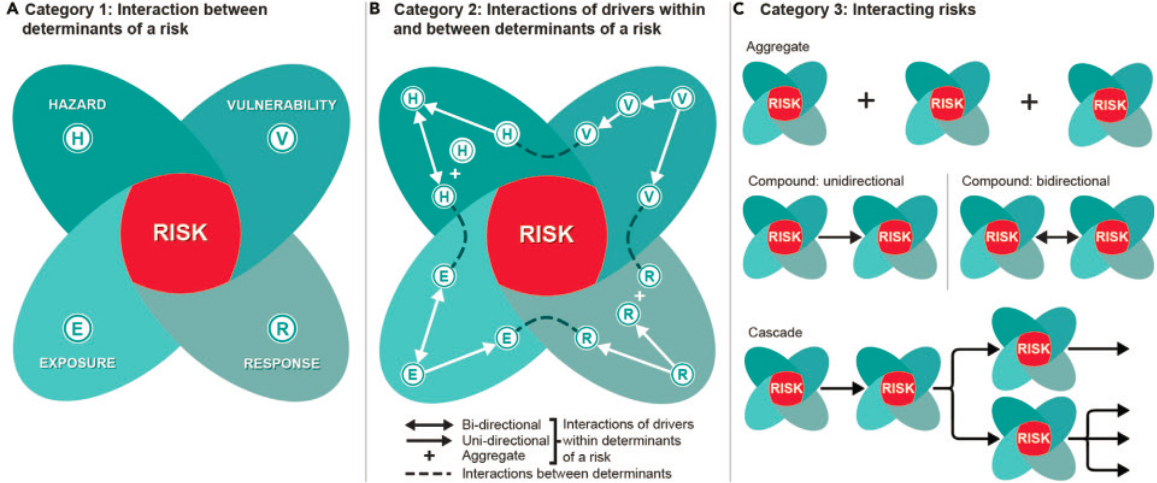

Kristie Ebi reflected on the progress in understanding risk components and their interactions between IPCC Working Groups I and II over the past 20 years. She emphasized the importance of recognizing the complexity of risk, particularly in the context of compounding and cascading risks. Ebi discussed a framework for understanding these risks, outlined in three categories of complex climate change risk: (1) interaction between determinants of a risk, (2) interactions of drivers within and between determinants of a risk, and (3) interacting risks (see Figure 2-6). Determinants include hazard, vulnerability, exposure, and response; a driver is an individual component

SOURCE: Simpson et al. (2021).

of these, such as temperature or income, that interacts to affect the overall nature of risk (e.g., heat mortality) (Simpson et al., 2021). Ebi noted that societal responses to risk are complex and likely to change significantly, with social tipping points expected to precede climate tipping points.

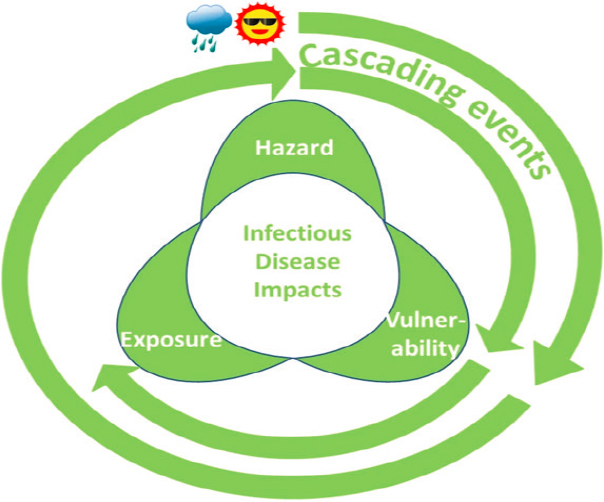

Using health as an example, Ebi illustrated the dynamics of cascading events resulting from climate change risks. She explained that various climate-sensitive health outcomes can arise from factors such as increased temperatures and extreme weather events. Demographic, socioeconomic, environmental, and other factors can influence the magnitude and patterns of risks (Haines and Ebi, 2019). Different exposure pathways can lead to climate-sensitive health outcomes, such as injuries and fatalities from extreme weather events. Ebi emphasized the cascading effects due to the interactions between hazard, vulnerability, and exposure (see Figure 2-7; Semenza et al., 2022). She explained how climate hazards, such as extreme weather events, can be exacerbated by societal weaknesses, leading to additional hazards, such as floodwaters tainted with pathogens or increased mosquito populations. These infectious disease risks can cause cascading events, amplified by newly acquired vulnerabilities, ultimately exposing populations to waterborne or mosquito-borne disease outbreaks, respectively. Ebi emphasized that more than 80 percent of the risks of the changing climate affect children. Because they bear the brunt of the risk to many hazards, she said, focusing on them is important when examining compounding and cascading risks.

Elisabeth Gilmore continued the discussion on the intricate dynamics of social response to climate change. Applying an IPCC Working Group II perspective to cascading and nonlinear risks, she explores the complex dynamics in socioeconomic conditions and governance, perhaps even more so than climate change. She said that she focuses on vulnerability, distribution of adaptive capacity, management of these risks, and ways to generate more positive outcomes. In particular, she emphasized vulnerability as a key factor in societies’ ability to manage these risks, highlighting climate change as a multiplier of vulnerability. Using conflict as an example, she demonstrated how climate hazards exacerbate vulnerabilities, leading to conflict-affected countries trapped in both vulnerability and violence (Buhaug and von Uexkull, 2021).

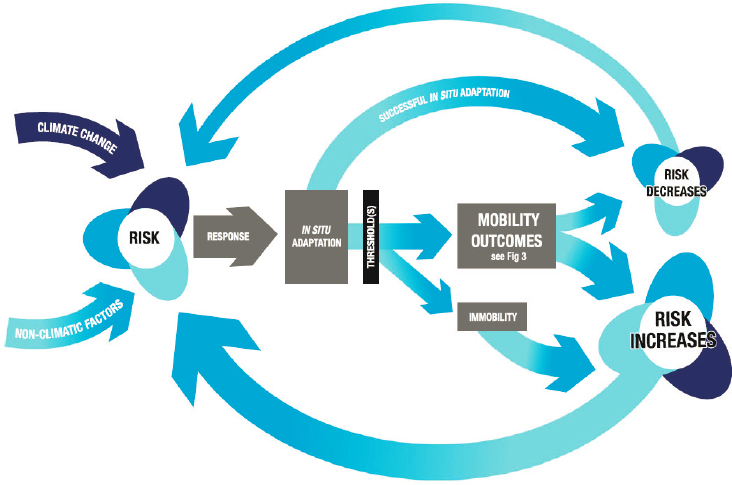

Additionally, Gilmore explored the impacts of migration, noting both positive and negative outcomes for households. She emphasized the importance of understanding the decision-making processes behind migration, influenced by climatic and nonclimatic factors, which can lead to a threshold at which mobility and immobility strategies come into play (McLeman et al., 2021). Gilmore said that when households have choice and agency, they tend to leverage human and financial assets, reducing their risks and generating positive outcomes for receiving and sending locations. On the

SOURCE: Semenza et al. (2022).

SOURCE: McLeman et al. (2021).

other hand, Gilmore explained, distress migration and involuntary immobility, driven by vulnerability, can generate negative outcomes and increase risks for these migrants. She highlighted that policies that support migrants, shifts away from narratives of migration as a security threat, and climate adaptation can improve outcomes.

INFRASTRUCTURE AND CLIMATE CHANGE

Mikhail Chester provided an overview of the relationship between infrastructure and climate change, emphasizing the macroeconomic implications of their interaction. He highlighted his research focus on understanding how climate dynamics impact infrastructure and lead to vulnerabilities, collapses, and failures. Chester emphasized the concept of “decoupling” between what infrastructure can currently do and what is required in a rapidly changing environment due to climate change. He pointed out that infrastructure design—from roads to power lines to stormwater pipes—traditionally relies on norms that are quickly unraveling due to a shifting climate.

Discussing challenges for the macroeconomy, Chester highlighted the vulnerability of aging infrastructure, complexity of modern infrastructure systems, and limitations of rehabilitating all infrastructure at the necessary scale and pace. Chester underscored the challenge of adapting legacy infrastructure to the landscape of climate change, technological advancements, and societal shifts. He noted that significant barriers to adaptation include the inherent rigidity in infrastructure technologies, slow governance processes, and lack of consideration for climate change uncertainty in engineering education. He proposed a shift toward designing infrastructure with failures in mind and emphasized the importance of integrated governance processes that manage failures while enabling adaptation. See Box 2-1 for a longer discussion on governance.

When asked about key factors contributing to infrastructure vulnerability, Chester outlined three.

- Older infrastructure is generally more vulnerable due to being less tolerant of changes associated with climate.

- Infrastructure operating close to or beyond its capacity is at risk, especially when climate stressors are added.

- Relying solely on more rigid infrastructure approaches to combat environmental challenges is likely to be problematic in the face of deep uncertainty associated with climate change.

Ultimately, Chester stressed the need for infrastructure to become more agile and flexible, emphasizing the importance of a focus on “coupling”

BOX 2-1

Governance

Reevaluating governance structures emerged as a discussion topic, particularly regarding infrastructure planning and development. Chester highlighted the importance of understanding the governance structures of agencies responsible for infrastructure, which he described as a “division bureaucracy” inherited from the railroads in the 19th century. Although it is efficient under stable conditions, Chester explained that it can struggle during instability. He suggested reimagining governance structures, especially during unstable periods, and exploring models that allow for bottom-up decision making as potentially more effective.

When asked about bridging the gap in decoupling, Chester emphasized the importance of agility and flexibility in infrastructure. He questioned the conventional approach of planning infrastructure to last a specific number of years (e.g., 50 or 80 years) without considering deep uncertainty in climate and technological changes. Instead, Chester proposed a shift toward agility, flexibility, and a more probing and testing approach for complex infrastructure systems.

infrastructure with environmental dynamics to ensure rapid responses to climate change impacts.

DISCUSSION

During the open discussion, the panelists covered a wide range of topics, including the economic impacts of AMOC collapse, vulnerability in economic structures, and U.S. infrastructure governance challenges. A participant inquired about leading indicators or key variables for climate and economic tipping points, particularly in complex, nonlinear systems. Armstrong McKay discussed early warning signals in complex systems that may exhibit bifurcation, increased variability, and slower variability as they approach thresholds. However, he acknowledged the challenges of distinguishing signals from noise and that some systems can lack any warning signal. He stressed that a lack of early warning signals does not indicate that these thresholds are not approaching or being reached.

Ebi noted the importance of focusing on specific time frames and regions for policy decisions and cautioned that models with distant future positive outcomes may have significant near-term negative outcomes. On the broader question of early warning indicators for societal and security risks, Ebi highlighted the uncertainty in predicting tipping points at various scales. She mentioned the challenges of monitoring and measuring societal vulnerability over the long term, noting the lack of comprehensive datasets.

She expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of existing short-term indicators as reliable forewarnings of significant societal changes.

Probing deeper into vulnerabilities, one participant asked about economic structures as vulnerability multipliers or dampeners. Gilmore highlighted that some of the vulnerability is driven by existing development strategies, which can promote maladaptation, but expressed optimism regarding the potential for policy and governance to address vulnerabilities, particularly in distributions of risk and inequities. She emphasized the importance of equitable development and methods to enable people to enact self-determined strategies for alleviating climate and economic stressors. Ebi emphasized considering specific contexts and prioritizing relevant criteria across different contexts, considering both high- and low-income countries. Huber discussed differential vulnerability to extreme heat and humidity, noting that adjustments to labor and capital to flow as a compensating mechanism in economic optimization models, such as the GTAP model, can absorb shocks. However, he acknowledged that these adjustments tend to favor high-income countries.

Another participant asked the panelists to address the apparent disconnect between economic climate impact analyses and climate modeling. Gilmore responded that some of it may come from the specifications in the economic models that might be missing many steps in the processes, leading to underestimations. She pointed to the need to consider feedback, dependencies, vulnerability, armed conflict, and migration (see Box 2-2),

BOX 2-2

Migration and Transdisciplinary Research

Ebi highlighted the opportunity for transdisciplinary collaboration in addressing the issue of integrating migration. She suggested learning from macroeconomic modeling focused on shocks (see Chapter 3) and incorporating migration as one of the shocks. Gilmore acknowledged the complexity of integrating migration into macroeconomic models and pointed to innovations in agent-based modeling that differentiate between households and consider individual characteristics and aspirations. She recognized the importance of understanding who is moving and the types of mobility available. Despite advances in data, she highlighted the challenge in evaluating such models. Similarly, Huber discussed efforts to use household surveys to gather information for decision making but emphasized the need for a substantial investment, effort, and time to improve the representation of migration in models. Lori Hunter, University of Colorado Boulder, highlighted the scholarship on migration from demographers, emphasizing the opportunity for collaboration between demographers and macroeconomic modelers to ensure the effective integration of migration into models.

emphasizing the potential ethical implications of modeling some economic impacts as inevitable rather than societally mandated. Similarly, Ebi highlighted the tendency for economic models to use overly simplistic damage functions. She suggested transdisciplinary collaboration to improve modeling estimates by incorporating insights from various sectors. Huber and Armstrong McKay echoed Ebi’s point about damage functions, emphasizing that many negative climate impacts are not effectively integrated into economic models. Huber questioned the assumption of perpetual growth built into these models, overriding other considerations, that may not be realistic. Overall, the panelists’ responses underscored the importance of more realistic and interconnected modeling that considers climate impacts’ complexity, vulnerabilities, and ethical implications.

One participant asked each panelist to provide the top three research gaps they think need to be addressed in the space of cascading and compounding climate risks. The responses highlighted the benefit of improved modeling, a deeper understanding of vulnerability, the integration of social dynamics and infrastructure components, and a shift toward transformative change and equitable solutions. Armstrong McKay suggested improving Earth system models with a focus on resolving tipping point dynamics, such as improving spatial resolution. Furthermore, he noted the importance of exploring interactions to understand cascades. He proposed model intercomparison that runs simpler models in large ensembles to have a more statistical approach to interactions and cascades. Last, he noted the importance of considering early warning signals, including better metrics for these signals.

Ebi highlighted vulnerability as a key research gap, emphasizing the need for a deeper understanding of vulnerability metrics that can be applied across diverse contexts. Second, she emphasized the importance of SSPs and the need to extend them to better integrate social dynamics. Last, she noted the importance of addressing social tipping points and working toward greater integration across societal sectors. Gilmore agreed that the need to understand fundamental drivers of vulnerability is important, considering internal measures that may have more salience to affected individuals. She also called for more transformative change that foregrounds equity and justice considerations. Last, she highlighted the importance of improving how equity, justice, and distribution dynamics are integrated into these efforts, specifically through co-production approaches.

Huber acknowledged that physical climate system uncertainties are relatively small compared to the uncertainties of translating physical modeling into social systems impacts. He recognized the need for improved understanding of social system dynamics, better methods, and more accurate data. Furthermore, he stressed the importance of a more dynamic relationship between physical and social sciences with the infrastructure component,

noting the importance of bringing engineers to the table. Finally, he said that it will be important to understand the role of institutions—whether they are government or social—in finding optimal pathways to the future.

Chester suggested investing in agility and flexibility in infrastructure, allowing for adaptability as climate and social needs change. Highlighting the interplay between social, ecological, infrastructural, technological, and cyber systems, he suggested that creative solutions may be needed for infrastructure to provide more adaptive capacity. Finally, he emphasized the role of infrastructure as knowledge systems and called for a shift in thinking, innovation, and restructuring of mental models among civil engineers to address the evolving challenges of climate change.

To close, Lenton asked each expert to highlight examples of methods to better capture systemic risks in the process. Ebi mentioned increased collaboration and funding support from various sources to facilitate collaborative modeling among different sectors and disciplines. She stressed the need for collective solutions, incorporating diverse perspectives. Gilmore supported the idea of diverse lenses in modeling, suggesting that different perspectives, such as a strong mobility lens, can reveal new possibilities for systemic change. She urged funders to consider interventions that incorporate various lenses, particularly in data collection and drawing on diverse knowledges, to gain a comprehensive understanding of climate change impacts and responses.

Huber discussed the importance of building specific modules within modeling frameworks, such as migration and poverty modules. He highlighted the need for co-development throughout the modeling process—extending beyond professors and research scientists—and suggested transparency in sharing frameworks and results. He said that opening the frameworks could create a more inclusive, collaborative ecosystem. Armstrong McKay agreed with the importance of additional resources and the development of interdisciplinary models. In summary, the panelists stressed the importance of collaboration, funding support, diverse perspectives, co-development, and transparent frameworks to advance the understanding of systemic climate-related risks and develop effective solutions.