Emerging Hazards in Commercial Aviation—Report 2: Ensuring Safety During Transformative Changes (2024)

Chapter: 4 Safety Culture

4

Safety Culture

In theory, an organization’s safety culture will drive how well it can actively manage safety, and the practices required for safety management can serve as a learning process to mature that safety culture. In this chapter we focus on two critical aspects of safety management: organizational processes and culture. First, as part of its overall charge to “assess whether … available sources of information are being analyzed in ways that can help identify emerging safety risks” the committee is also tasked to “draw on the results of FAA’s [Federal Aviation Administration’s] annual internal safety culture assessments and also advise the agency on data and approaches for assessing safety culture to assure that FAA is identifying emerging risks to commercial aviation.”

Thus, the first section of this chapter provides an update on the annual safety culture assessment by FAA’s Office of Aviation Safety (AVS).1 Because other safety-critical industries, particularly nuclear power, have begun to explore the safety culture of regulators and its effect on operators, the second section introduces this relatively new concept and discusses whether this construct should be adopted by AVS. Consistent with the overall emphasis of this report on new entrants, the third section describes strategies FAA could use to ensure that industry—especially “new entrants”—develops

___________________

1 AVS is responsible for the certification, production approval, and continued airworthiness of aircraft; certification of pilots, mechanics, others in safety-related positions, commercial airlines, operational and maintenance operations, civil flight operations; and for safety regulations. See https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs.

mature safety cultures by monitoring, evaluating, and responding to the safety management practices industry adopts.

STATUS OF THE OFFICE OF AVIATION SAFETY’S SAFETY CULTURE ASSESSMENT

Safety Culture and Its Assessment

From Culture to Safety Culture

Organizational culture is widely acknowledged by experts in the field as difficult to define and challenging to measure. Many experts rely on theory developed by Schein (2010), who proposes that organizational culture has three levels:

- Artifacts—visible manifestations of culture (logos, history, headquarter design/layout, dress code, styles of communication, how people are rewarded or punished, how to get ahead, how conflicts are managed);

- Espoused beliefs and values—mission statements, stated core principles, written policies, public statements, etc.; and

- Shared assumptions—collective understanding of how an organization faces and overcomes significant challenges, including adapting to external events and internally integrating these adaptations.

For Schein, shared assumptions are typically deeply rooted and taken for granted, so much so that they are not readily articulated by participants or leaders. Shared assumptions within organizations include collective understanding about past behavior and values, including how important decisions were reached in the past, and their consequences, in response to significant challenges for the organization as a whole or within operating divisions.

Weick and Sutcliffe (2015) summarize and slightly modify Schein’s formulation as follows:

In Schein’s view, culture is defined by six formal properties: (1) shared basic assumptions that are (2) invented, discovered, or developed by a group as it (3) learns to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration in ways that (4) have worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, (5) can be taught to new members of the group as the (6) correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems. The one addition we would make to point 6 is that culture is as much about practices and actions as it is about mindsets. [Emphasis added.] When we talk about culture, therefore, we are talking about

- Assumptions that preserve lessons learned from dealing with the outside and the inside;

- Values derived from these assumptions that prescribe how the organization should act;

- Practices or ways of doing business;

- Artifacts or visible markers that embody and give substance to the espoused values.

Artifacts are the easiest to change, assumptions the hardest.

What Schein has spelled out in careful detail, people often summarize more compactly, “how we do things around here.” For our purposes, we amend that slightly and argue that culture is also “what we expect around here.”

There are several overlapping conceptualizations of the safety culture of an organization. At its core, it can be thought of as the priority that an organization assigns to safety as represented by its assumptions, values, practices, and artifacts. In the private sector, this priority often reflects the priority given to safety against other goals since companies must be profitable to survive and the only way for an airline to be 100% safe is to not operate. That said, companies have demonstrated the ability to operate at very high levels of safety while also being profitable. For example, under the leadership of Paul O’Neill over the 1989–2000 time period, Alcoa achieved a remarkable record of both safety and profitability. “O’Neill has been quoted as saying ‘Safety should never be a priority. It should be a prerequisite’” (Leveson, 2023, p. 430).

FAA’s conceptualization of safety culture, both for the companies it regulates and itself, has been influenced by Reason’s (1997) conceptualization of an “informed” culture and its four critical, interrelated subcomponents: a reporting culture, a just culture, a flexible culture, and a learning culture. From a safety perspective, great weight is placed on employees feeling free, if not obligated, to speak out about incidents or issues, even if they have made a mistake or violated a procedure. Creating this environment for openness requires ensuring that employee-reporters will not be punished or reprimanded for unintentional mistakes or violations. It also requires that (a) organizations focus on learning from mistakes, including building non-punitive reporting and information systems that inform decision making and (b) are flexible enough to change when processes or procedures are helping to create errors or not adequately minimizing them.

Influenced by the views of anthropologist Geert Hofstede (Reason, 1997, p. 194), Reason’s view of safety culture is rooted in what it “has” and “does” (Schein’s artifacts and espoused beliefs and values) and less so on what it “is” (Schein’s shared assumptions). Reason’s emphasis on the “having” and “doing” dimensions of safety culture has been embraced in

definitions of the essential traits of organizational safety culture by national and international regulatory bodies.

The recent formulation of safety culture traits by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is a modest re-wording of an earlier policy statement by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (IAEA, 2020; Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2011) (see Table 4-1). While recognizing that theorists and organizations vary in their definitions of safety culture traits and emphasis on them, an extensive body of research supports the traits defined by a committee of the National Academies of Sciences (NASEM, 2016). Recent AVS research reports on safety culture (Key et al., 2023; Worthington et al., 2023), as well as the culture survey AVS used in 2023–2024, have relied heavily on the IAEA 2020 formulation.

Assessment of Safety Culture

The committee’s first report (NASEM, 2022) provides an overview of best practices in organizational culture assessment; these best practices, in turn, are more fully summarized in NASEM (2016) and IAEA (2019). In this report, the committee further emphasizes that culture assessment is an ongoing process that involves management engagement with employees through surveys, focus groups, dialogue, interviews, and other means of probing and understanding how organizational mindfulness and commitment to safety permeates and varies across an organization. Culture or climate surveys are often popularly believed to represent culture, which they can only do at a surface level and at a specific moment in time. Moreover, the metrics such surveys generate are “the least important aspect of culture assessment and change” (NASEM, 2016, p. 150). Their primary benefit is to “prompt conversations about and broaden understanding of the organization’s safety processes, as well as [senior leadership and employee] participation in generating innovative paths forward and continuing conversation to learn from these efforts” (NASEM, 2016, p. 150, citing Carroll, 2015).

AVS Culture Assessment 2022

The initial survey instrument that AVS used was the Human Synergistics’ Organizational Culture Inventory (OCI), a representation of organization culture based on a definition of culture as “the shared beliefs and values guiding the thinking and behavioral styles of its members” (Cooke and Rousseau, 1988). Thus, the OCI is a general-purpose survey of organizational culture, not a safety culture survey per se. The OCI is described as an instrument for assessing:

TABLE 4-1 Safety Culture Organizational Traits

| 1. Leader Responsibility | Leaders demonstrate a commitment to safety in their decisions and behaviors. Leaders are role models for safety. |

| 2. Individual Responsibility | All individuals are personally accountable for safety. All individuals feel it is their duty to know the standards and expectations and rigorously fulfill those standards and expectations. There is personal ownership for safety. They have a commitment that promotes safety both individually and collectively. |

| 3. Problem Identification and Resolution | Issues potentially impacting safety are systematically identified, fully evaluated, and promptly resolved according to their significance. |

| 4. Decision Making | Decisions are systematic, rigorous, thorough, and prudent. Leaders support conservative decisions and the ability to recover quickly from unforeseen circumstances. Leaders follow the decision-making process. Responsibility for decision making is clear. |

| 5. Work Planning | The process of planning and controlling work activities is implemented so that safety is maintained. Work is managed in a deliberate process in which work is identified, selected, planned, scheduled, executed, and critiqued. The entire organization is involved in and fully supports the process. All relevant parts of the organization work together to support the process of controlling work. |

| 6. Continuous Learning | Learning is highly valued. The organizational capacity to learn is well developed. The organization employs a variety of approaches to stimulate learning and improve performance, including human, technical, and organizational aspects. Individuals and teams are highly competent and seek opportunities for improvement. |

| 7. Raising Concerns | Personnel feel free to raise safety concerns without fear of retaliation, intimidation, harassment, or discrimination. The site creates, maintains, and evaluates policies and processes that allow personnel to raise concerns freely. |

| 8. Communications | Communications support a focus on safety. Leaders use formal and informal communication to frequently convey the importance of safety. The organization maintains a variety of communication channels including direct interaction between managers and workers. Effective dialogue is encouraged. Effective communication in support of safety is broad and includes workplace communication, reasons for decisions and expectations. |

| 9. Work Environment | Trust and respect permeate the organization. A high level of trust is cultivated in the organization. Differing opinions are encouraged, discussed, and thoughtfully considered. Employees are informed of steps taken in response to their concerns. |

| 10. Questioning Attitude | Individuals remain vigilant for assumptions, anomalies, conditions, behaviors, or activities that can adversely impact safety and then appropriately voice those concerns. All employees are watchful for and avoid complacency. They recognize that minor issues may be warning signs of something more significant. Individuals are aware of conditions and alert to potential vulnerabilities. |

SOURCE: IAEA, 2020.

12 sets of norms that describe the thinking and behavioral styles that might be implicitly or explicitly required for people to “fit in” and “meet expectations” in an organization or organizational subunit. These behavioral norms specify the ways in which all members of an organization—or at least those in similar positions or locations—are expected to approach their work and interact with one another. (Cooke and Szumal, 2000)

Organizations are assumed in the OCI to have clusters of 12 norms and behaviors that can be bundled into Constructive, Passive/Defensive, and Aggressive/Defensive categories. The OCI is designed to estimate how organizational perceptions and behaviors are distributed across and within these three dimensions. Senior managers or organizations using the OCI can use this three-part construct to define their ideal organizations, which can be compared to how employees view the organization as indicated from results from the survey.

AVS staff briefed the committee on the results of the OCI in September and October 2023. The survey was conducted during the month of September 2022 by Human Synergistics and achieved a 30% response rate. The results of the OCI survey suggested that the staff viewed the organization as more “Passive/Defensive” and less “Constructive” than senior managers’ aspirations for the organization. AVS subsequently used focus groups to probe more deeply into employee perceptions but did not have the results of that process at the time of the 2023 briefings.

Although widely used by many other organizations to assess culture, the OCI does not directly measure specific safety culture traits such as those listed in Table 4-1. Translating the results of a general culture survey to one that focuses on the specific safety-related values and behaviors of safety culture requires a considerable inferential leap to map the values and behavioral styles the OCI measures against the values and behaviors that organizations’ safety culture would reflect.

At AVS’s request, Human Synergistics appended 13 questions to the standard OCI. Ten of these questions probed employee perceptions about AVS’s openness to, and encouragement of, AVS employees reporting safety

concerns, doing so without blame or recrimination, existing mechanisms for reporting, and management responsiveness to reports. These questions addressed employee perceptions of Reason’s “reporting and just culture”; only three questions focused on AVS’s “flexible and learning culture.” AVS officials indicated to the committee that some respondents found the formal OCI survey to be lengthy and they had difficulty understanding the relevance of the questions to their work and the working conditions in AVS.

AVS has decided against using the OCI for its second annual safety culture assessment and rely instead on a set of questions designed to address safety culture traits directly. The committee views this as appropriate. Although undue importance should not be placed on the survey element of culture assessment, starting with a survey of employee perceptions based on key organizational safety culture traits is likely to lead more directly to insights about the strong and weak aspects of organizational safety culture.

AVS Safety Culture Assessment 2023

For the 2023 survey stage of its safety culture assessment, FAA tasked experts at its Civil Aerospace Medical Institute to develop a survey based on the 10 IAEA traits along with a few supplemental questions drawn from other relevant sources, such as the IAEA safety culture perceptions survey (IAEA, 2017) and an organizational culture survey used by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2020). The speed with which the second AVS survey was developed precluded extensive psychometric testing, but the committee’s review of the questions indicates face validity with the IAEA traits. Following considerable outreach from senior management as well as from the neutral third party that conducted the survey (to ensure anonymity), AVS employees were invited to participate and given four weeks to respond (October 12 and November 9, 2023). The total questionnaire had more than 80 questions, but in an effort to improve the response rate, respondents were randomly given a total of 20 questions, with each IAEA trait being addressed with two questions. On average, employees were able to complete the survey in less than 8 minutes.

AVS officials briefed the committee on the general results on March 11, 2024. The overall response rate reached 37%, which represented a 7 percentage point improvement over the 2022 survey. AVS officials indicated this response rate approached the 40% normally experienced in surveys of federal government employees, but they also acknowledged that it fell well short of the 70% or more achieved in the safety culture surveys conducted periodically by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2020). Responses were anonymous, but the demographic information provided suggests that the distribution of respondents across frontline and management positions was consistent with that of the AVS

workforce. The general results of the survey as interpreted by AVS officials indicated that AVS employee commitment to safety is evident in the behaviors and work practices of individuals.

Furthermore, individuals adhere to established standards (i.e., policies, processes). AVS also appears to have a strong “just” and “reporting” culture. Employees feel free to speak up without fear of retribution. In terms of being a “learning” culture, AVS officials pointed to areas needing improvement in the IAEA traits of “communications” (leadership explaining reasons for decisions) and “continuous learning” (better sharing of lessons learned and in use of results to make improvements in safety oversight). Regarding AVS’s overall safety culture, there are also opportunities for greater “leadership responsibility” (greater visibility of senior leaders as role models in their commitment to safety). Regarding AVS’s “flexible” culture, officials expressed uncertainty about the amount of flexibility available to AVS given that its oversight derives from specific rules derived from its legislated authority and the limits of its resources. Plans for follow-up to respondents were in review by senior management at the time of the briefing.

REGULATORY SAFETY CULTURE

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)2 investigation of the Fukushima Daiichi disaster implicated the culture of Japan’s primary nuclear safety regulator as contributing to the multiple failures that occurred in preventing, mitigating, and responding to the massively disruptive earthquake and tsunami of 2011 (IAEA, 2015). The Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA)3 subsequently set forth an initial set of principles and attributes of regulatory safety culture (NEA, 2016). This section explores possible lessons AVS could draw from this relatively new concept and the status of research about how it could be assessed.

Drawing from Leveson’s (2023, pp. 640–657) review, five relevant threats to the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency’s (NISA’s) effectiveness in anticipating and preventing the Fukushima disaster include (1) a lack of independence from industry, (2) unwillingness or inability to act decisively in response to credible warnings, (3) inadequate staffing, (4) insufficient technical competence, and (5) complacency due to an “unrealistic risk assessment and reliance on redundancy.”

___________________

2 IAEA is a United Nations (UN) agency created in 1957 to work with UN member states and stakeholders worldwide promote “safe, secure, and peaceful nuclear technologies.” See https://www.iaea.org/about/overview/history.

3 NEA is an advisory organization representing nuclear power regulators from 31 nations that operates under the auspices of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). See https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/tro_5705/about-us.

Safety Culture Principles and Attributes for Regulators

NEA’s 2016 report, based on insights of experts and nuclear regulators from several nations, set forth an initial set of principles and attributes for the safety culture of nuclear regulators (see Table 4-2). This guidance follows the authors’ recognition that, if regulators expect the organizations that they regulate to have good safety cultures, regulators have to understand and model safety culture principles and behaviors themselves.4

Fleming, Harvey, and Bowers (2022) further refined the NEA list of regulatory culture principles in their effort to develop a survey instrument that regulators could use to initiate assessment of their safety cultures:

- Leadership commitment to creating a positive safety culture;

- Unwavering ethical standards;

- Transparency through communication;

- Proactive risk informed approach;

- Continuous learning and self-improvement.

Fleming, Harvey, and Bowers’s list overlaps with that of NEA but gives greater emphasis to their principle 2 of “unwavering ethical standards,” which they interpret to include regulator independence, compared to the NEA attribute 2.c of “moral courage” and “doing the right thing.” Their principle 4 substitutes “proactive risk-informed approach” for NEA’s principle 4 of “implementing a holistic approach.” Both lists overlap with most of the IAEA safety culture traits for operators, but also indicate different levels of emphasis more appropriate for regulators than operators. For example, the IAEA trait 5 regarding the planning of work is appropriate for operators directly managing the hazards associated with their work, whereas the NEA attribute 4.c for a “clear regulatory framework” would document what regulators expect to see in the organizations they are regulating and, presumably, as well, what they will do to assure that the entities they regulate are doing what is expected of them.

Regarding the regulatory culture failures associated with the Fukushima disaster, NEA attribute 1.e is the only one that speaks directly to leaders ensuring that adequate resources are available to carry out the regulator’s safety mission. Although it may be implicit in the overall construct of NEA’s principles and attributes, they do not speak directly to the independence of the regulator or to its technical competence. The AVS 2023 safety culture survey questions, although they could be more pointed, out of the five NISA failures, address elements of four: independence (in the sense that decisions reflect safety regardless of industry or other pressures), competence (the

___________________

4 IAEA guidance to regulatory self-assessment accepts this conclusion, but its recommended practice for regulatory self-assessment nonetheless appears to rely on a survey instrument that it also recommends for use by nuclear power plant operators (IAEA, 2019).

TABLE 4-2 Principles and Attributes of Regulator Safety Culture

| Principles | Attributes |

|---|---|

| 1. Leadership for safety is to be demonstrated at all levels in the regulatory body. |

|

| 2. The culture of the regulatory body promotes safety and facilitates cooperation and open communication. |

|

| 3. All staff of the regulatory body have individual responsibility and accountability for exhibiting behaviors that set the standard for safety. |

|

| 4. Implementing a holistic approach to safety is ensured by working in a systematic manner. |

|

| 5. Continuous improvement, learning and self-assessment are encouraged at all levels in the organization. |

|

SOURCE: NEA, 2016. CC BY 4.0.

emphasis is on training, which is a necessary but not sufficient condition for competence), resource adequacy, and questioning attitude. The Fleming, Bowers, and Harvey initial survey instrument, discussed next, also covers four of the five indicated NISA failures. Although they appear to be implied, the ability and willingness of the regulator to take decisive action in response to an existing or potential emerging hazard is not addressed directly in any of the regulator culture constructs proposed to date.

Regulator Culture Assessment

Fleming, Harvey, and Bowers’s aim was to develop a psychometrically tested survey instrument for regulators since none of the ones developed for regulators have applied this technique to help ensure quality. They began by evaluating the three then-existing models of regulator behavior they were aware of (Bradley, 2017; Fleming and Bowers, 2016; NEA, 2016). With the help of 13 nuclear power industry safety culture experts, Fleming, Harvey, and Bowers organized the principles and attributes into 11 dimensions (see Box 4-1).5

Working with 14 other safety culture experts, Fleming, Harvey, and Bowers (2022) developed and tested a 71-item survey instrument using an initial convenience sample of 114 international regulatory staff. However, after factor analysis of survey results, six theoretically important dimensions were not correlated, leadership, ethics and moral courage, independence,

BOX 4-1

Hypothesized Dimensions of Regulator Safety Culture

- Leadership Actions

- Regulator Independence

- Responsibility and Accountability

- Continuous Learning, Improvement, and Competence

- Questioning Attitude

- Ethics and Moral Courage

- Psychological Safety

- Systematic Regulatory Approach

- Decision Making

- Interdisciplinary Internal Cooperation

- Openness, Transparency, External Cooperation, and Communication

SOURCE: Fleming et al., 2022.

___________________

5 Note that in 2019 the Safety Management International Collaboration Group (SMICG) developed its own instrument for “initial” aviation regulator self-assessment (SMICG, 2019, Appendix 1). The 40-item survey appears to cover some of the same dimensions as indicated in Table 4.3, but the theory or principles on which the survey was developed are not explained. SMICG does recognize that assessment requires far more than a survey.

interdisciplinary internal coordination, decision making, and questioning attitude. The lack of correlation with such key safety culture dimensions led the authors to recommend use of a random sample of a larger set of respondents to better ensure valid results. At the time of this writing in early 2024, the concept of regulatory safety culture is still in a nascent state with relatively little research and analysis to support it (Fleming et al., 2022). However, the committee believes the regulatory safety culture concept has promise and encourages AVS to study and learn from the regulatory failures at Fukushima as well as other cases involving regulatory inadequacies, such as the Deepwater Horizon/Macondo well disaster of 2010 (NAE and NRC, 2012). AVS could also monitor and learn from the ongoing efforts to develop the regulatory safety culture concept and a self-assessment instrument for it.

Findings and Recommendations: The Office of Aviation Safety’s Safety Culture Assessment Including Regulatory Safety Culture

Finding 4-1: The committee supports the AVS shift in 2023 to a survey based on the 10 IAEA safety culture traits and its efforts to improve the response rate. The appointment by AVS of a manager with experience in the safety culture assessment process is appropriate. These steps represent good progress, although the committee observes that the congressional request for the annual assessment of the AVS safety culture was enacted in December 2020; while the second survey had been completed at the time of the committee’s briefing in March 2024, the overall second annual assessment was incomplete.6

Finding 4-2: A safety culture survey represents but the initial step in an ongoing dialogue and discovery process between senior management and employees about the safety culture of an organization and how it can be strengthened. For the committee to carry out its charge of reviewing AVS’s annual safety culture assessment requires greater insight into the steps being taken by AVS to assess its culture beyond the survey and how it is using what it is learning to strengthen the AVS safety culture.

Finding 4-3: Success in strengthening the AVS safety culture depends heavily on the direct, visible, and frequent engagement of senior AVS

___________________

6 In its mandate that AVS conduct an annual safety culture assessment in December 2020, Congress specified that the assessment include an annual survey of AVS employees. The committee’s charge is to review the annual safety culture of AVS mandated in P.L. 116-260, Division V, Sec. 132. The scope of its review does not include other FAA organizations.

management with front-line employees in enabling, enacting, and elaborating the AVS safety culture. These are not responsibilities that can be delegated to the manager responsible for the safety culture survey. At the time of this writing, the committee lacks evidence about such a level of engagement by the highest levels of AVS management in learning from safety culture assessment and implementing actions aimed at strengthening AVS’s safety culture.

Finding 4-4: The emerging concept of the safety culture appropriate for a regulator reflects the view of IAEA that, if regulators expect the organizations that they regulate to have good safety cultures, they have to understand and model safety culture principles and behaviors themselves. To date, there is insufficient research in defining, and distinguishing between, the traits and behaviors of the safety cultures of regulators and the safety culture of those they oversee. The emerging concept of regulatory safety culture is one that AVS can monitor and learn from. Moreover, FAA could support the development of this concept and its assessment through its research budget.

Finding 4-5: The safety culture of any large organization does not change quickly. An annual survey is too frequent to pick up shifts in employee perspectives about the organization’s safety culture. (The Nuclear Regulatory Commission conducts a survey every 3 to 5 years.) The ongoing assessment process of the AVS safety culture can also employ appropriate cycles of other processes, such as focus groups, ongoing dialogue with front-line employees, and input from the employee voluntary reporting system can help AVS articulate and mature its safety culture.

Recommendation 4-1: Congress should continue requiring the Federal Aviation Administration Office of Aviation Safety (AVS) to assess its safety culture, but allow AVS the flexibility to reduce the frequency of the safety culture survey, and in alternate years allow AVS to focus more of its annual assessment efforts on formal and informal communication by leadership, conduct of focus groups and other forms of dialogue with employees about their perceptions of AVS’s safety culture, and feedback to employees about what leadership is learning through the assessment process and the changes it is making in response. Within this process, AVS should identify two or three major goals the organization has for strengthening its safety culture and a short list of actions it will be taking, and evaluating in the next assessment, to help achieve these goals. Likewise, AVS should identify the safety culture traits and behaviors it should model as a regulator to the industry organizations it oversees.

The committee, in its next study, will continue with its required review of AVS safety culture assessment, and will incorporate these items.

Recommendation 4-2: The safety culture assessment manager that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Office of Aviation Safety (AVS) has added to its staff should report regularly to the AVS Associate Administrator and the FAA Administrator, both of whom should be responsible for appropriate actions to enable a strong, and continuously improving, AVS safety culture.

MATURING SAFETY CULTURE ACROSS THE INDUSTRY

Innovation may ultimately bring societal benefits. However, such innovations may stress current industry with changes in business model and changes from their historic products and operations; likewise, innovators may include new entrants who, as noted in Chapter 1, may not have an organization and culture steeped in aviation safety. The very deeply embedded assumptions and behaviors (Schein, 2010) that make an entrepreneurial new entrant successful in product development may be counter to what is required to achieve FAA certification and operational approval.

However, organizational cultures can be steered to improve, as described in the next three parts of this section:

- Safety culture maturity;

- Regulator role in safety culture maturity; and

- New entrant safety management and metrics and implications for AVS oversight.

Safety Culture Maturity

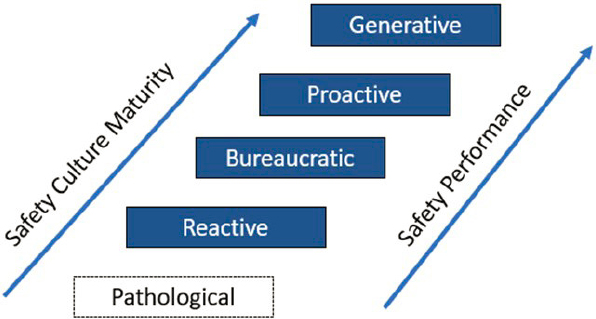

The safety culture maturity concept (Fleming, 2001; Parker et al., 2006; Westrum, 1993) illustrates stages of organizational safety culture maturity, which range from being uncommitted to safety to integrating safety into everything that an organization does. The safety culture maturity concept is not a predictive model nor, in itself, a specific guide to action. Rather, it can help people recognize that cultures vary along the dimensions of maturity it describes, use this concept to help them assess their organizations’ cultures, and illustrate how organizations’ safety cultures can grow through deliberate actions on the part of leaders and employees. However, it is simplified by its implication that organizations have monolithic cultures. In fact, organizations have subcultures that differ across levels and professions (Schein, 2010). The culture of large organizations also likely differs across divisions and regional offices. Moreover, the stages that organizations are

depicted to move through do not necessarily progress upward. Organizations can regress due to a change, or lack of, leadership or they can simply become complacent about the presence of latent conditions that, in combination with local conditions, can penetrate layers of defense (Reason, 1997). Progression up the maturity ladder, and even maintenance of an organization’s place on the ladder requires active engagement by management and employees. That said, the maturity concept is a useful heuristic for representing how safety cultures can grow stronger and how regulators can influence that process.

The stages of safety culture development postulated by Parker, Lawrie, and Hudson (2006) build on the work of previous scholars and have since been modified by many others and applied across multiple safety-critical industries (Filho and Waterson, 2018). The descriptions of the maturity stages below draw on Hudson (2001) and Parker, Lawrie, and Hudson (2006) and have been modified to apply to the commercial aviation industry.

Pathological: Companies at this stage lack any real commitment to safety, as indicated by its name (see Figure 4-1). This category was included as a benchmark, highlighting organizations that lack the requirements and expectations that exist in commercial aviation.

Reactive: An organization that is reactive with regard to safety implies that its communications are mostly top-down; management believes failures are caused by individuals; incident information is being gathered but not necessarily volunteered and procedures changed in response but without follow-up; regulations are implemented but without strong commitment; and management statements about safety are not always believed by the workforce.

SOURCES: Parker et al., 2006; SMICG, 2019.

Bureaucratic: In this stage, management is exercising top-down control of safety but with little bottom-up information about what might be going wrong; the workforce is becoming more involved in items such as improving procedures and reporting incidents but receives little feedback from management; a safety officer is collecting and reporting statistics to management and developing standardized procedures but with few checks on their use or employee understanding of them; safety indicators are increasingly quantitative but may not be measuring actual risk.

Proactive: In the proactive stage, management engagement in safety is more visible and tangible to the workforce; information is flowing back and forth between senior management and the front line; safety discussions are permeating into other meetings; the workforce is more engaged; procedures are rewritten with input from employees; training is complemented with measures to determine competency; safety is given high priority; the safety director has a high-status role in advising top management; frequent discussions are held across the organization about near misses and their proximate, organizational, and cultural causes and how to reduce them; and emerging hazards are being identified and monitored, and corrective actions taken.

Generative: The generative stage may be more aspirational than common, but at this stage safety would be fully incorporated into all decision making and behaviors, and the organization is committed to continuous improvement in all phases of its safety management and performance. Indicators of such maturation would be that of an organization fully dedicated to learning through communication and information flowing freely across the organization; hazards being anticipated and managed before they result in incidents; management and the workforce working in effective partnerships; and employees at all levels actively resisting complacency by constantly focusing on what might go wrong, which Reason (2000) also described as a mindset of “intelligent wariness.”

One would not expect new entrants that are developing and proposing new technologically based aviation services to be prepared to operate systems safely at the proactive stage of cultural maturity. However, having a well-conceived set of safety policies, procedures, operating plans, and SMS, including generating and sharing information with FAA demonstrating effective safety management, could be conditions FAA places on allowing new entrants to test their proposals and ultimately begin to implement them (if successful) and expand them (if warranted) through demonstrated safety performance. This is part of the additional data collection and analysis needing to be built into the safety assurance component of safety management discussed in the previous chapter.

Regulator Role in Safety Culture Maturity in the Industry

One approach for maturing a new entrant’ safety culture would be through collaboration and coaching from FAA, a role recommended by the Safety Management International Collaboration Group (SMICG) (2019).7 For a regulator to do so effectively, it would need to understand what a mature safety culture is, be fully cognizant of how its culture and behaviors are influencing the operators it regulates, and have sufficient competence in assessing the culture of operators and influencing them effectively. A regulator that is itself at the bureaucratic stage of maturity and reliant on prescriptive authorities and regulations may struggle to help operators mature beyond this stage.

In 2020 the U.S. Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General (OIG) faulted FAA for not providing its aviation safety inspectors with guidance on how to “evaluate and oversee an air carriers’ safety culture” (USDOT OIG, 2020). Given the vague dimensions of safety culture, and multiple approaches needed for assessing it, evaluating the culture of an operator through inspections alone would be beyond what a regulator could be expected to accomplish. Consistent with the guidance offered above and in the committee’s first report, SMICG (2019) recommends use of a full set of quantitative and qualitative methods (such as surveys, workshops, and interviews) to assess an operator’s safety culture. However, AVS concluded that this level of assessment would (a) be too resource intensive for routine surveillance of certificate holders, (b) require specialized expertise, and (c) be inconsistent with FAA leadership direction in response to the OIG report to implement a method that was achievable by its existing workforce and could be incorporated into FAA’s Safety Assurance System (SAS)8 (Worthington et al., 2023).

AVS researchers therefore modified existing data collection tools in the SAS to prompt inspectors to record concerns about safety culture-related behaviors and activities across the seven organizational safety attributes used in the SAS.9 They also recommended additional training for inspectors in safety culture (Worthington et al., 2023). The AVS approach may be sufficient to train inspectors to identify and record surface level indicators of a weak safety culture. The data entered into the SAS can be used by the

___________________

7 SMICG was founded by FAA, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency, and Transport Canada Civil Aviation. It is a joint cooperation between many aviation regulatory authorities for the purpose of promoting a common understanding of safety management and Safety Management System (SMS)/State Safety Program (SSP) principles and requirements.

8 SAS is FAA’s risk-based, data-supported oversight tool used by AVS offices to carry out certification, surveillance, and continued oversight of operational safety. It contains policies, processes, and data collection tools that AVS can use to capture data when conducting oversight.

9 Procedures, Responsibility, Authority, Controls, Interfaces, Process Measurement, and Safety Ownership.

principal AVS staff responsible for certificate holders to trigger a formal evaluation. However, whether AVS has the collective expertise to assess safety culture is not obvious given that best practice in safety culture assessment is an ongoing process involving multiple methods (quantitative and qualitative). Instead, evaluation of an organization’s safety management process and SMS may be a more tractable and promising approach.10

Federal Aviation Administration Monitoring of Safety Culture Through Safety Management Systems

This chapter begins with the observation that an organization’s safety culture will drive how well it can actively manage safety, and the practices required for safety management can serve as a learning process to mature that safety culture. Enabling, enacting, and elaborating can change culture through implementing, practicing, learning, and improving (Vogus et al., 2010). The conditions AVS places on new entrant safety management and its monitoring of the new entrant’s safety management processes would provide AVS opportunities to encourage organizational learning and safety culture maturity.

Insights from Safety Management into New Entrant Safety Culture

By their nature, new entrants are proposing to provide novel services with novel technologies by new organizations. As noted in the previous chapters, established criteria, measures and processes for both the safety risk management and safety assurance components of safety management cannot rely entirely on historic practice in aviation. Likewise, examining the organizational structure and culture components of safety management, new organizations may lack experience in structuring an organization to emphasize safety. The safety management plan proposed by a new entrant would provide FAA insight into how a new entrant proposes to address these safety issues and concerns, and then its execution would provide the data, analysis and process for change management and continuous improvement that FAA could use to assess how effectively they are addressing these concerns.

Evaluation of Proposed Safety Management Systems and Processes

AVS can analyze any applicant’s proposed safety management plan by analyzing the descriptions of the components and elements of the SMS. In

___________________

10 In this chapter, the committee relies on the ICAO (2018) SMS formulation, particularly the safety risk management and safety assurance processes of SMSs.

terms of organizational structure and culture, this assessment can include questions such as:

- How insightful the stated safety policy is, whether it was developed in concert with representatives of its workforce, whether it has all the necessary elements to allow for an “Informed Culture,” and how management will communicate and reinforce this safety policy;

- How the new entrants’ management commitment to the stated safety policy will be expressed through communications, resource allocation, and managers’ evaluations and compensation;

- The experience, competence, seniority, authority, and access of the top safety official to senior leadership; and

- How the competence of the workforce would be maintained through training and testing for competence.

Execution of Safety Management

The information generated as part of safety management would guide new entrants’ development of a safety culture, and the sharing of this information would provide AVS with insight into new entrants’ commitment to safety management and safety culture. The data collected during safety risk management and safety assurance should also include indicators of organizational and cultural concerns, such as tolerance for routine operating errors; failures in carrying out procedures and policies or updating them in a timely way in response to employee feedback; and weakening and misalignment of organizational culture (differences in espoused and actual behavior). Other indicators that could be monitored include staffing levels, turnover, and competency records; resource allocation for training; task performance records; defect tracking systems; maintenance and repair effectiveness and backlog, internal and independent audits, missed audits, corrective actions taken, and missed deadlines in corrective action plans (CIEHF, 2016).

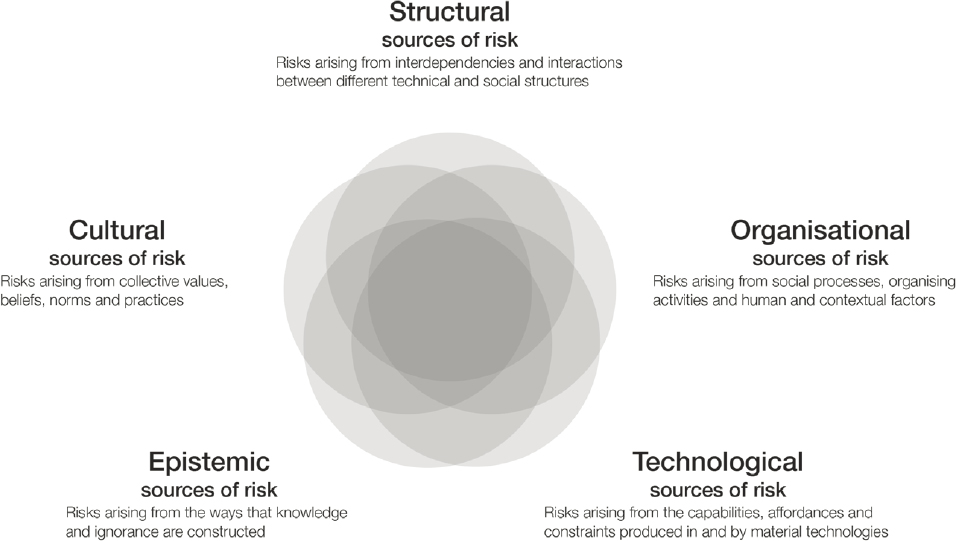

A framing for these risks must extend beyond just separating measures of the technology, of the operation of the technology, and of the organization: Macrae’s (2021) framework, for example, defines and categorizes sociotechnical risks of autonomous and intelligent systems (AISs) and the multiple interactions among advanced technologies, organizational operations, limits in the understanding of AIS performance, and organizational culture (see Figure 4-2).

SOURCE: Macrae, 2022. CC BY.

Finding 4-6: The components of safety management, the data they generate, and their implementation in a SMS, can provide FAA with a primary mechanism for oversight of organizations’ safety culture maturity, how safety management will be integrated into operations and management by new entrants, and how safety management can be applied throughout the organization for continual improvement.

Finding 4-7: Promising safety indicators to support both industry organizational structures and safety culture and FAA oversight would include testing of employee competence in understanding and executing risk controls; feedback between front-line employees and system developers regarding identification and management of hazards; identification and response to unanticipated emerging hazards within the organization; results from employee voluntary reports, SMS audits, audit deficiencies, and corrective action plans and timeliness of response to them; and other indicators of the organizations preoccupation with what might go wrong and continual improvement.

The findings here on safety culture contribute to recommendations made in the next chapter, which discusses how safety management needs to be integrated across disciplines, organizations, and the lifecycle of new products and operations.

REFERENCES

Bradley, C. S. 2017. A Framework for Regulator (Oversight) Safety Culture: How Regulatory Culture Influences Safety Outcomes in High Hazard Industries (doctoral dissertation). Fielding Graduate University.

Carroll, J. S. 2015. Making sense of ambiguity through dialogue and collaborative action. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 23.

CIEHF (Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors). 2016. Human factors in barrier management. https://ergonomics.org.uk/resource/human-factors-in-barrier-management.html.

Cooke, R., and D. Rousseau. 1988. Behavioral norms and expectations: A quantitative approach to the assessment of organizational culture. Group and Organizational Studies 13.

Cooke, R., and J. Szumal. 2000. Using the Organizational Culture Inventory® to understand the operating culture of organizations. In N. Ashkanasy, C. Wilderom, and M. Peterson (eds.). Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate. Sage.

FAA (Federal Aviation Administration). 2015. Safety Management Systems for Aviation Service Providers. Advisory Circular 120-92B, p. 3.

Filho, A., and P. Waterson. 2018. Maturity models and safety culture: A critical review. Safety Science 105.

Fleming, M. 2001. Safety Culture Maturity Model. HSE Books.

Fleming, M., and K. Bowers. 2016. Regulatory Body Safety Culture in Non-nuclear HROs: Lessons for Nuclear Regulators. No. IAEA-CN-237.

Fleming, M., K. Harvey, and K. Bowers. 2022. Development and testing of a nuclear regulator safety culture perception survey. Safety Science 153.

Hudson, P. 2001. Safety culture: Theory and practice. Paper presented at the RTO HEM Workshop “The Human Factor in System Reliability: Is Human Performance Predictable?” held in Siena, Italy, 1–2 December 1999, and published in RTO MP-032.

IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency). 2015. The Fukushima Daiichi Accident: Technical Vol. 2, Safety Assessment. https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/AdditionalVolumes/P1710/Pub1710-TV2-Web.pdf.

IAEA. 2017. IAEA Safety Culture Perception Survey for License Holders. Working Document. https://gnssn.iaea.org/NSNI/SC/TRWSSCA/Working%20Material%20incl%20IAEA%20SCPQ-LH/IAEA%20Safety%20Culture%20Perception%20Questionnaire%20for%20License%20Holders_V12.pdf.

IAEA. 2019. Guidelines for Safety-Culture Self-Assessment by the Regulatory Body. https://www.iaea.org/publications/13562/guidelines-for-safety-culture-self-assessment-for-the-regulatory-body.

IAEA. 2020. A harmonized safety culture model. IAEA Working Document. https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/20/05/harmonization_05_05_2020-final_002.pdf.

ICAO. 2018. Safety Management Manual, 4th ed. https://skybrary.aero/sites/default/files/bookshelf/5863.pdf.

Key, K., P. Hu, and I. Choi. 2023. Safety culture assessment and continuous improvement in aviation: A literature review. DOT/FAA/AM-23/13.

Leveson, N. 2023. An Introduction to System Safety Engineering, Chapter 14. MIT Press.

Macrae, C. 2022. Learning from the failure of autonomous and intelligent systems: Accidents, safety and socio-technical sources of risk. Risk Analysis 42(9). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/risa.13850.

NAE and NRC (National Academy of Engineering and National Research Council). 2012. Macondo Well Deepwater Horizon Blowout: Lessons for Improving Offshore Drilling Safety. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. Strengthening the Safety Culture of the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NASEM. 2022. Emerging Hazards in Commercial Aviation—Report 1: Initial Assessment of Safety Data and Analysis Processes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NEA (Nuclear Energy Agency). 2016. The safety culture of an effective nuclear regulatory body. OECD. https://www.oecd-nea.org/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-12/7247-scrb2016.pdf.

Nuclear Regulatory Commission. 2011. Final safety culture policy statement. Federal Register (76/114), June 14, pp. 34773–34778. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2011-06-14/pdf/2011-14656.pdf.

Nuclear Regulatory Commission. 2020. NRC Office of the Inspector General Safety Culture and Climate Survey 2020. https://nrcoig.oversight.gov/reports/other/nrc-office-inspector-general-safety-culture-and-climate-survey.

Parker, D., M. Lawrie, and P. Hudson. 2006. A framework for understanding the development of safety culture. Safety Science 44.

Reason, J. 1997. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Ashgate Publishing.

Reason, J. 2000. Human error. BMJ 320:768.

Schein, E. 2010. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th ed. Jossey-Bass.

SMICG (Safety Management International Collaboration Group). 2019. Organizational culture self-assessment tool and guidance for regulators. https://skybrary.aero/articles/organizational-culture-self-assessment-tool-regulators.

USDOT OIG (U.S. Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General). 2020. FAA has not effectively overseen southwest airlines’ systems for managing safety risks.

Vogus, T., K. Sutcliffe, and K. Weick. 2010. Doing No Harm: Enacting, Enabling, and Elaborating a Culture of Safety in Health Care. Academy of Management Practices.

Weick, K., and K. Sutcliffe. 2015. Managing the Unexpected: Sustained Performance in a Complex World, 3rd ed. Wiley.

Westrum, R. 1993. Cultures with requisite imagination. In J. A. Wise et al. (eds.). Verification and Validation of Complex Systems: Human Factors Issues. Springer-Verlag.

Worthington, K., R. Gay, P. Hu, I. Choi, and D. Schroeder. 2023. Safety culture assessment by aviation safety inspectors. Aviation Safety, Office of Aerospace Medicine, Federal Aviation Administration, DOT/FAA/AM-23/39.