Emerging Hazards in Commercial Aviation—Report 2: Ensuring Safety During Transformative Changes (2024)

Chapter: 2 Current Predictive Processes for Aviation Safety Risk Management Relative to Transformative Changes in Aviation Technologies and Operations

2

Current Predictive Processes for Aviation Safety Risk Management Relative to Transformative Changes in Aviation Technologies and Operations

The starting point for managing aviation safety must be during design of new technologies and operations and continue through their testing and evaluation before implementation. Known as safety risk management, this discipline includes appropriate processes for identifying hazards, assessing their risk, and implementing appropriate safeguards and mitigations commensurate with risk; these are vital contributions to identifying, categorizing, and analyzing emerging safety trends in aviation. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) plays three vital roles in safety risk management:

- Certification of individual products, personnel and practices of designers, producers, maintainers and aircraft operators (managed by the Office of Aviation Safety [AVS]).

- Establishing the collective Operating and Flight Rules and procedures by which aircraft are operated within the National Airspace System (NAS) (managed by AVS and Air Traffic Operations [ATO]).

- Deployment, operation and maintenance of the air traffic management system (new equipment, operations and procedures) that provide aircraft separation, air traffic control and air traffic management (managed by the ATO).

This chapter focuses on the safety risk assessment processes for which FAA’s AVS organization is responsible, namely, oversight of those operating in the NAS, reviews how these processes are conducted and assesses their capability to provide safety risk management (SRM) for transformative changes in aviation technologies and operations.

SUMMARY: FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION PROCESSES FOR CERTIFICATION

To better understand FAA’s current processes for certifying technologies, flight operations, operators, and personnel, the committee invited testimony from current and former representatives from FAA and examined the “parts” of the 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) defining current processes.1

There are five main categories of FAA certificates and approvals needed to operate an aircraft commercially in the NAS:

- Certification for Products and Articles: Under the purview of regulation 14 CFR Part 21, type certification includes the approval of new aircraft, engines, and propellors, which may then be incrementally updated through Supplemental Type Certifications (STCs). The regulations define a number of categories, each with more detailed regulations covering their airworthiness standards, including Part 23 for Normal Category Airplanes, Part 25 for Transport Category Airplanes, Part 27 for Normal Category Rotorcraft, Part 29 for Transport Category Rotorcraft, Part 33 for Aircraft Engines, and Part 35 for Propellors. Parts Manufacturer Approvals (PMAs) are the mechanisms for approving other aircraft systems that can be installed on multiple different aircraft, ranging from simple wiring harnesses and brackets to sophisticated avionics systems; if their use requires modifications to the aircraft, then the aircraft may also require an STC. This process certifies that the product meets applicable air worthiness requirements, with the resulting approval then serving as intellectual property that the holder may use to directly produce the aircraft or product, or may license to others.

- Production Certification: Under the purview of regulation 14 CFR Part 21, a certified product has to be produced in an organization that has proved to FAA that they can faithfully reproduce an airworthy design. The certification is unique to the manufacturer. Common types of articles (tires, seats, etc.) may be applied that meet the minimum performance standard (MPS) defined under a Technical Standard Order (TSO), but their installation still needs to be shown by the manufacturer to comply with the type certification or approval for the combined system (Parady, 2023).

- Airworthiness Certification: Under the purview of regulation 14 CFR Part 21, each aircraft must meet established standards to

___________________

1 “Parts” here refer to the parts of Chapter 1 of CFR Title 14 “Federal Aviation Regulations,” which defines classes of aircraft operators and establishes the standards that each must apply.

- Operator Certification: Commercial operations are primarily divided into three tiers: Parts 91, 135, and 121. Part 91 establishes the general operating and flight rules for all operations, and by itself allows only those commercial operations in which an operator does not carry passengers for compensation or hire, such as flight training, aerial surveying crop dusting, and aircraft owners paying services to provide the pilots to transport them in their own aircraft. Part 135 adds additional specifications for operators seeking to provide commuter and on-demand operations and Part 121 adds further specifications for scheduled domestic, international, and large-aircraft charter flights; these higher-level operating certifications require, among other things, additional pilot training, flight attendant training, maintenance, record keeping, scheduling, compliance to financial rules, etc. The certification is unique to the air carrier.

- Personnel Certification: Many types of personnel need to be certificated: Part 61 details certification of pilots, flight instructors and ground instructors, Part 63 details certification of other flight crew members (flight engineers and flight navigators), and Part 65 details certification of “airmen other than flight crew members” including air traffic control operators, dispatchers, mechanics, repairment, and parachute riggers. To illustrate what personnel certification covers using pilots as an example, pilots have to be approved across several dimensions, which includes their training, medical status (14 CFR Part 67), behavioral health, etc. Pilots earn a progression of types of certificates, ratings, and endorsements corresponding to different classes of aircraft and operations. The certification is unique to an individual pilot.

ensure it is in a safe operating condition. The certification is unique to an aircraft, which is usually indicated by serial numbers. The certification must be maintained over time and can be revoked if something happens to the aircraft. An airworthiness certification is issued to the operator/owner of the aircraft.

Three general trends exist within this certification structure. First, allowable risk, and the commensurate degree of safety that must be demonstrated, varies depending on the type of aircraft and operation. Relevant certification requirements establish standards relevant to these different aircraft and operations under different “Parts” of the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs). For example, light-sport aircraft and experimental aircraft are limited to private flights and thus have comparatively fewer, and less stringent, requirements for the operations, personnel, and technologies. In contrast, there are progressively more, and more stringent, requirements

for commercial operations of small aircraft, regional airline operations, and the most tightly regulated scheduled air transport operations. This report focuses on the more stringent requirements associated with commercial operations.

Second, FAA certification is structured around current technologies and operations. For example, the pilot is certificated for specific extant classes of aircraft, and the aircraft is mostly certified on the assumption that it will be flown by someone with the skills associated with current pilot certificates. With new technologies, these assumptions may not hold true, such as with an aircraft, otherwise appropriate for certification under the “airplane” class, whose flight control is automated to the point that there is no need for control mechanisms like “yoke and rudder pedals” and the pilot will not need to demonstrate manual flight control skills.

Third, each certificating office within FAA mostly requires demonstration of compliance using methods and measures that have been developed over years or even decades. In some cases, the regulations exactly specify requirements for demonstrating compliance to certification standards, established through a lengthy formal rule making process and development of associated industry standards. In many other cases, the regulations only specify a general requirement, and FAA has developed Advisory Circulars—more detailed guidance on a specific acceptable method for complying with a requirement named in the regulations. While ACs are not mandatory, they offer organizations an accepted method of compliance.2 As new technologies are developed, Industry Standards Development Organizations develop standards and associated testing guidelines to meet FAA’s safety requirements. In many cases, an FAA TSO or AC will, in turn, reference an industry standard and its guidance as a means of compliance with their order.

When seeking certification for technologies and operations fitting within these current structures, organizations generally identify which parts of the FAR apply, and work with the different offices within the FAA AVS to certify separately the technology, its production, the personnel, and their operations. Within each of these separate certification processes, the most unambiguous route is to apply existing demonstrated means of compliance such as provided by ACs and TSOs and referenced industry standards. There are often some gaps in the available guidance, which can be covered by “special conditions” as per 14 CFR Part 11 §11.19 when FAA finds “that the airworthiness regulations for an aircraft, aircraft engine, or propeller design do not contain adequate or appropriate safety standards, because of a novel or unusual design feature.”

At the time of this report, for example, a special condition has been proposed by Safran Electric & Power and posted in 2024 for public comment

___________________

2 For some examples, see https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/advisory_circulars.

for use of an electric motor as the primary source of propulsion for small aircraft certified under Part 23 (e.g., small training aircraft), following an original application for certification in 2020.3 The proposal cites several difficulties in applying the current regulations, 14 CFR §33, including:

The existing part 33 airworthiness standards for aircraft engines date back to 1965 [and] are based on fuel-burning reciprocating and turbine engine technology…. Therefore, the existing engine regulations in part 33 address certain chemical, thermal, and mechanically induced failures that are specific to air and fuel combustion systems operating with cyclically loaded, high-speed, high-temperature, and highly stressed components…. In addition, the technology comprising these high-voltage and high-current electronic components introduces potential hazards that do not exist in turbine and reciprocating aircraft engines.

The proposal then provides a substantive list of alternate requirements for certification.

Thus, when proposing transformative changes, organizations face a critical decision: Should they attempt to align with existing certification paths and existing operating procedures with current FAA certification processes? If they do, their process will likely depend on arguing for special conditions, waivers, and exemptions to the existing means of compliance, such as the example in the previous paragraph. They may also find that they need to adjudicate among different certificating offices when, for example, the autonomous aircraft they seek to certify requires different skills and tasks in the pilot certification process. Applicants have reported to the committee cases where they perceived a need to avoid new features for which there is no means of showing compliance, such as control stations supporting flight-critical functions for one or more remotely piloted aircraft, even when these new features may improve safety when viewed in a holistic safety risk management perspective.

Technically, it is allowable for organizations to propose different safety risk management processes to FAA tailored to their new attributes, instead of seeking certification under established means of compliance. However, the process is open-ended and starts with petitions: a petition for an exemption for an individual case, which must include why the request would be in the public interest and proof that the exemption would not adversely affect safety or provide an equivalent level of safety. In a broader case, petitions for rule making may ask for changes to federal aviation regulations and must address a number of societal concerns with cost and benefit, regulatory burden, and effect on the natural and social environments (14 CFR §11.71).

___________________

3 See https://drs.faa.gov/browse/excelExternalWindow/FR-SCPROPOSED-2024-05101-0000000.0001.

As an example, a petition submitted in May 2021 asked for exemptions from the regulations that prevent allowing use during on-demand commercial cargo operations of an aircraft reduced from its normal certified status to being certified experimental by adding the capability for nominal flight to be conducted by onboard autoflight and a ground station operator, with an onboard safety pilot ready to take over as necessary; these regulations include §61.113(a), §91.7(a), §91.319(a), §135.25(a), §135.93, §135.115, and §135.143(a) and (b). FAA’s response in June 2022 denying the petition demonstrates the careful attention to precedent and the detailed level of scrutiny that is applied, including seeking public comment.4

The committee does not have the access to specific data to assess the merits of this particular case, but note it is an exemplar of a key question with implementing transformative technologies and operations: How to gather the experience and data examining their safety in realistic conditions sufficient to gain approval? The petitioner stated that gathering sufficient data to prove safety only in separate, experimental conditions during non-revenue flights would be both “financially infeasible” and also “may not adequately represent actual part 135 operations.” In response, FAA stated that it “has previously issued multiple denials of exemptions in response to similar requests to operate an experimental aircraft for compensation or hire as presented in the petition” and that “the manufacturer must accomplish each major modification and alteration to the aircraft in accordance with FAA-approved data … to qualify the aircraft for a standard airworthiness certificate” to remove the limits on how and where it operates—and thus requiring all flight data in support of certification be gathered outside commercial operations in the United States. This reflects the fact that some operators are collaborating with the U.S. military for authorization to fly in the NAS (Clouse, 2024), and others first started operations in other countries (Baker, 2017).

SUMMARY: AIR TRAFFIC AND GENERAL OPERATING RULES WITHIN THE NATIONAL AIRSPACE SYSTEM

FAA operates the NAS, within which they define the flight rules by which all entities will interact. These flight rules are defined in Subchapter F “Air Traffic and General Operating Rules,” which spans Parts 89 through 107 of the 14 CFR. These rules are also translated into the point of view of specific actors through documents such as the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) for pilots5 and the FAA Job Order (JO) 7110.65 Air Traffic Control

___________________

4 See https://drs.faa.gov/browse/excelExternalWindow/FAA0000000000000000000000EX19138.0001.

5 See https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/aim_html.

for air traffic controllers.6 Appendix A describes, as an exemplar, how the requirements in 14 CFR §91 for instrument landing system approaches are then further codified and detailed in the design of airspace and approach procedures, and in the training and testing material for pilots in the AIM and in JO 7110.65 for air traffic controllers.

The current rules and procedures for the NAS has evolved over decades, constantly being refined any time new safety (or efficiency) concerns have come to light. However, they assume many things about aircraft and pilots. For example, 14 CFR §91 assumes that a pilot is onboard and can visually look out the window. In visual flight rules, this visual capacity is the basis for “see and avoid” of other aircraft, for avoiding terrain and obstacles, and for maneuvering in the traffic pattern around the airport. This visual capacity is required specifically in 14 CFR §91.175 for the transition from performing an approach on instruments to landing the aircraft by visual reference, and must be in place for the pilot and aircraft to be allowed to operate under instrument flight rules.

Throughout this collective set of specifications defining NAS procedures, there are many references to existing certification standards; for example, an instrument flight procedure may require that the aircraft is certified within a designated vehicle “class,” which stipulates many aspects of the vehicle’s performance, that the ground-based aids to navigation are confirmed to be in operation, and that the pilot has specific ratings within the current system of pilot certification. Likewise, this collective set of specifications provides the performance and safety requirements for many other elements of the NAS: the standards for Certified Professional Controllers, for example, trace to the specifications of NAS procedures, as do the requirements for all the systems supporting the controllers, ground infrastructure at airports, ground navigation aids, etc. (FAA, 2005). Thus, an applicant requesting changes to NAS operations may also be creating requirements for other personnel and other systems throughout the NAS, whose safety also needs to be verified.

In some cases, the same aircraft may operate under different flight rules depending on where or when it flies: for example, a small unmanned aircraft system (sUAS) may operate within newer 14 CFR §107 flight rules tailored to UAS operations as long as its radar transponder is OFF and its Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) Out equipment is not in transmit mode (and many UAS will not even install these equipment)—but, if the UAS desires to operate beyond the limits of 14 CFR §107 it may instead operate within the general flight rules of 14 CFR §91 if this equipment is turned on, the many additional requirements for the aircraft certification, pilot

___________________

6 See https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/atc_html.

certification, and so on are met, and the aircraft as operated by its remote pilot demonstrates it can perform all the required flight operations.

Especially if the ATO organization has not been involved from the start, when the technology changes, there can be a substantial lag after a product’s certification until updates to operating rules, and all the corresponding changes in airspace design, pilot and controller training, and so on, allow for new, different operations capitalizing on that technology. For example, enhanced flight vision systems (EFVS), which combines imagery from imaging sensors with flight information to show the runway environment during approach and landing, were first certified by FAA in 2001.7 However, because 14 CFR §91.175 still required pilot visual acquisition of the runway published decision altitudes/heights or minimum descent altitudes, use of EFVS to enable landing in lower visibility conditions—the motivation for implementing the technology—was then only incrementally allowed through a lengthy process. For example, an AC published in 2010 provided a process by which operators could make specific requests to use EFVS, to be considered on a case-by-case basis.8 Ultimately, following a Notice of Proposed Rule Making in 2013, use of EFVS by pilots was permitted without requiring operators to get special approval under a final rule first published in December 2016 and amended in January 2017.9

Highlighting the complexity of operating the vehicle in a new way enabled by a new technology, this EFVS final rule involved amendments in the General Operations and Flight Rules (i.e., the addition of a section, 14 CFR §91.176,10 allowing an alternative to 14 CFR §91.175) and corresponding changes to 14 CFR §66 adjusting pilot training and recent flight experience, changes to the rules within which aircraft operated by air carriers certificated under 14 CFR §121 and §135 are allowed to initiate and continue an instrument approach, and aircraft certification rules to allow portrayal of vision system video on a heads-up display in 14 CFR §23, §25, §27, and §29 (FAA, 2017). These amendments became effective in March 2018.

This example typifies how merely certifying a new technology does not necessarily translate to allowing for its use in the NAS. The collective set of regulations and guidance defining the general operating and flight rules of the NAS also must be updated if any change to operations is required, particularly if these new operations impact other stakeholders in the system, including other aircraft and air traffic control.

___________________

7 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2001-06-18/pdf/01-15333.pdf.

8 See https://www.faa.gov/documentlibrary/media/advisory_circular/AC%2090-106.pdf.

9 See https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/12/13/2016-28714/revisions-to-operational-requirements-for-the-use-of-enhanced-flight-vision-systems-efvs-and-to.

10 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title14-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title14-vol2-part91.pdf.

RELATING CURRENT FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION PROCESSES TO FORESEEABLE TRANSFORMATIVE CHANGES TO TECHNOLOGY AND OPERATIONS

An instance where the difficulties of new entrants proposing transformative new technologies and operations led to a significant change in certificating processes has been the rapid wide-spread development of sUASs. The first FAA airworthiness certificate for a civil unmanned aerial vehicle was issued in 2005.11 With the growing number of applications to certify UASs, FAA established the UAS Integration Office in 2012 and, by 2013, they began issuing type certificates for UAS. This immediately enabled case-by-case approval of specific operations such as managing wildfires (FEDWeek, 2013) and arctic surveys (FAA, 2012). FAA issued their first broad operational rules for the use of sUAS in 2016.12 Since the establishment of the UAS integration office and its commensurate Part 107 regulations, there are more than 781,000 registered sUAS and more than 375,000 licensed sUAS pilots as of February 2024.13 These Part 107 regulations only directly apply, however, to a limited set of conditions, including operations controlled by a ground pilot via Visual Line of Sight (VLOS), flight under 400 feet Above Ground Level, and vehicles weighing under 55 lbs. Part 107 ends with a description of how to apply for waivers to 10 limits currently in Part 107, and in the past 4 years the FAA UAS Integration Office reports issuing more than 600 waivers to Part 107 regulations.14

However, the UAS Office and Part 107 stand out as a singular development. Other proposed transformative changes to technologies and operations today face similar challenges in navigating the certification process as small UAS did before Part 107 was issued in 2016. Looking forward, FAA is faced with a myriad of new entrants to the airspace, proposing transformative new type of operations using substantially different technologies and architectures, creating a challenge an order of magnitude more complex than previous modernization efforts.

In reviewing the current regulations and processes for safety risk management via certification and operational approval, the committee noted their thoroughness and the decades of experience that they represent. The flip side of these established processes, however, becomes apparent when evaluated for their ability to predict the risk of transformative changes to technology and operations. These processes can be sufficiently specific to current technology and operations that they may be inappropriate for evaluating the safety risk of transformative changes. During the committee’s

___________________

11 See https://www.faa.gov/uas/resources/timeline.

12 See https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/uas/resources/policy_library/Part_107_Summary.pdf.

13 See https://www.faa.gov/uas.

14 See https://www.faa.gov/uas/commercial_operators/part_107_waivers/waivers_issued.

workshops, which brought together FAA personnel from the safety organization with industry proposing transformative changes to technology and operations, the committee was impressed with the openness of FAA officials who engaged in the workshops and briefings about their recognition of the need to accommodate transformative changes. However, these officials also noted that they envision the need for substantial amounts of testing and evaluation, and they do not yet have established metrics and criteria for applicants to plan toward. Likewise, the committee noted that such accommodations are not pervasively reflected through the line personnel in their organizations.

Finding 2-1: Proposals for certifying transformative changes pose a unique challenge when current methods of demonstrating compliance do not sensibly describe their characteristics. Literal adherence to the existing regulations may unnecessarily complicate and delay any attempt at certification or suggest workarounds that do not necessarily support safety. FAA’s role should be viewed as ensuring an acceptable level of risk while at the same time providing a reasonable path for innovation within the broad intent of safety risk management.

Recommendation 2-1: The Federal Aviation Administration Office of Aviation Safety should evaluate current regulations, guidance, and standards to determine if they limit or preclude certification of transformative changes in technologies and commensurate changes in personnel, production, and operating certificates, or appear to disincentivize new features that may enhance safety in different ways than historically assumed. Where such a situation is found, certification processes and standards should be updated to promote effective safety risk management within these new developments, including collaboration with industry where appropriate.

Promoting safety risk management without unduly limiting or delaying the introduction of transformative change in the NAS will require new ways of doing business. It will require a thorough understanding of the operational environment (procedures, equipage, etc.) into which a new aircraft, technology or way of operating will be integrated, as well as analysis of risk in situations in which current distinctions between the functions provided by different personnel and by technology, and where geographically and organizationally they are situated, may no longer apply. Currently, the offices within AVS and ATO that provide safety risk management in certification and in developing new operating rules are largely structured as independent entities. The committee identified numerous cases that cannot be comprehensively addressed independently by current AVS and ATO offices, such

as technologies that may not fit current distinctions of what functions are performed on the aircraft versus on ground-based systems and what functions are performed by humans versus machine; novel flight operations that are different from, yet still need to interact with, current airspace routes and procedures; novel operator practices for safety management; and novel personnel roles not covered by current requirements for personnel certification and training. Thus, addressing transformative changes to technology and operations will require the offices within AVS, and between AVS and ATO, to work together in ways they have not typically done.

Finding 2-2: For most types of operations, the FAA AVS does not currently have mechanisms for comprehensive safety risk management that spans the different organizations certifying technologies, personnel, and operating certificates, and governing the general operating and flight rules of the NAS. Since the regulatory offices are organized around how the NAS operates today, transformative changes can be difficult, if not impossible, to address.

Recommendation 2-2: The Federal Aviation Administration should establish cross-cutting positions, staffed by officials responsible for examining proposed transformative changes that simultaneously seek to manage safety and risk by purposeful, integrated changes to technologies, personnel, and operating certificates, and authorized to identify suitable means of compliance for, and certify, such transformative changes based on their collective mitigation of risk.

PERFORMANCE-BASED STANDARDS

As stated earlier, the committee found that promoting safety risk management without unnecessarily limiting the introduction of transformative change is a challenging problem, which is particularly magnified by certification methods and metrics that focused on historic technology and personnel roles. One specific method to reduce this challenge is to increasingly apply performance-based standards. The term “performance-based standard” is defined here as one that stipulates metrics of performance in executing a flight-critical function, regardless of the technology and personnel executing the function and where they are situated. By eschewing prescriptive standards that establish specific technoluogies or equipment, and instead defining performance outcomes that must be achieved, industry is free, even encouraged, to find innovative solutions that meet a safety performance requirement. For example, a prescriptive standard for an emergency exit would specify something like “Emergency exits must be movable windows, panels, canopies, or external doors that provide a clear

and unobstructed opening large enough to admit a 19-by-26-inch ellipse.” A performance standard might say, “The aircraft must be designed to facilitate rapid and safe evacuation in conditions likely to occur following an emergency landing.” With this shift from prescriptive to performance-based standards, the metrics governing certification are focused on safety, while also being open to innovative methods of meeting the requirement.

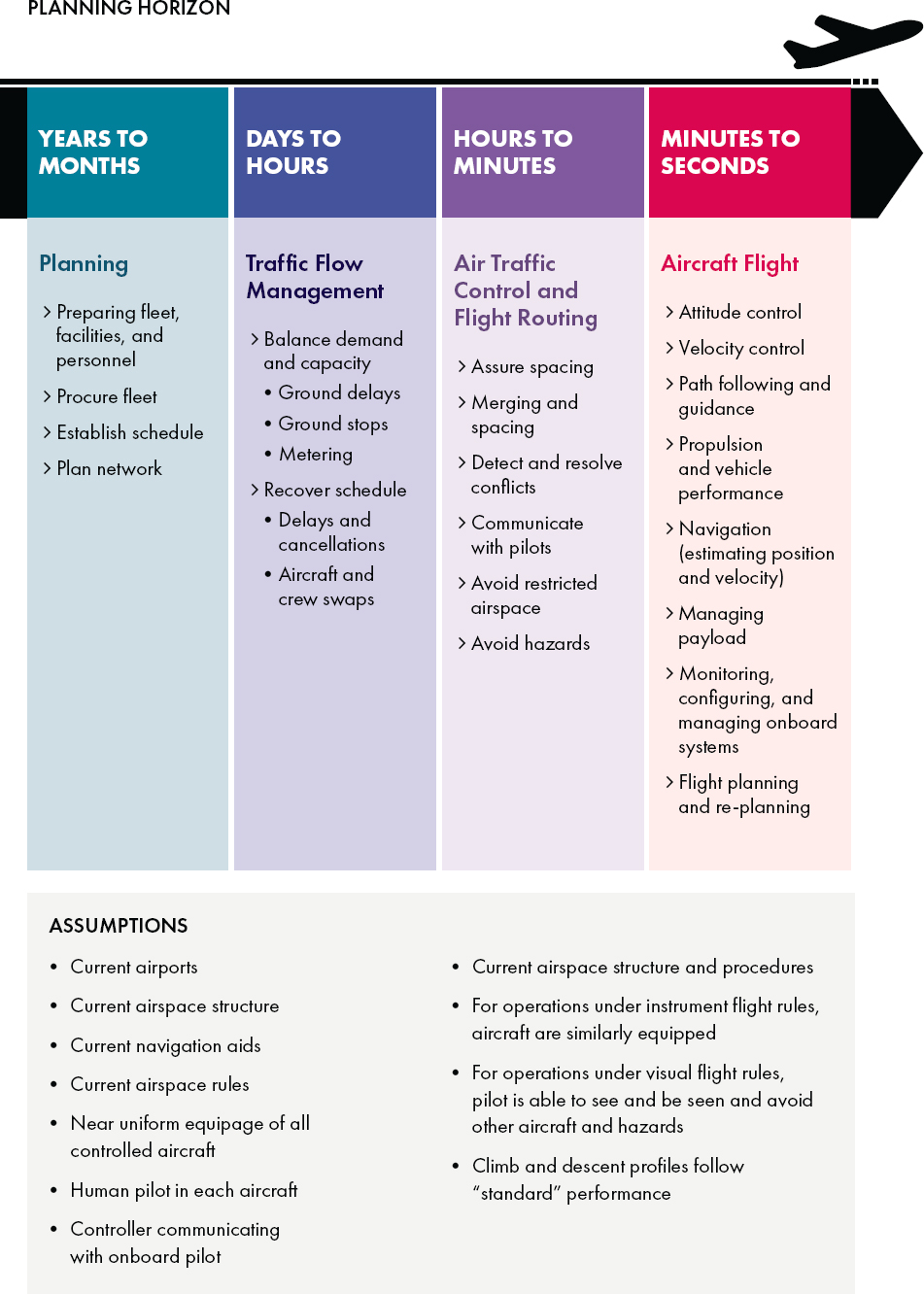

The NAS has enjoyed a decades-long exemplary safety record due in part to the layered levels of safety assurance for air traffic operations. If a safety issue makes it through one layer, for example, a demand/capacity imbalance creating a high density of aircraft in one sector of the airspace, air traffic control separation assurance will ensure that aircraft remain a safe distance apart. If that layer fails, onboard collision avoidance systems provide the last line of defense against an accident. However, as illustrated in Figure 2-1, these layers are predicated on a list of assumptions reflecting current technology and operations. These assumptions are then often deeply embedded in regulations and standards; transformative changes upend these assumptions and expose where standards are specified in terms appropriate only for current systems and thus do not allow for innovation.

Not all these assumptions are required for safe flight: what is required is effective execution of the set of critical functions as shown in Box 2-1, spanning the safe flight of each aircraft, aircraft respecting airspace rules and procedures, and aircraft remaining separated from hazards including hazardous weather, terrain, and other aircraft. How an aircraft performs these functions may vary. For example, if the pilot is in the aircraft, there may be no need for a ground control station with a reliable communication link to the aircraft; on the other hand, if the aircraft is remotely piloted, then a ground-based pilot and control station may need to demonstrate they can nominally perform these functions, with the additional requirement that any potential gaps or delays in air/ground communication must be compensated for by onboard capabilities.

Since the 1930s, government and industry have worked together to develop technical standards for critical components of the NAS that can be used as a means of compliance with FAA regulations. These have been upgraded as the system has evolved. However, most standards have been prescriptive. For example, 14 CFR §25.1303 specifies a list of specific instruments that must be installed on large aircraft, and that must be visible from each pilot station; with some transformative technologies, other types of sensors may provide equivalent information and/or there may not be a pilot station onboard the aircraft.

For some functions in some cases, FAA and industry have recently moved away from prescriptive standards to performance-based standards. Standards bodies, such as the RTCA (originally chartered as the Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics) and the American Society for

BOX 2-1

Aircraft Safety-Critical Functions

Flight

- Attitude control

- Velocity control

- Path following/guidance as appropriate for each phase of flight

- Propulsion and vehicle performance

- Navigation (technically, estimating vehicle position and velocity)

- Managing payload

- Monitoring, configuring, and managing onboard systems (including sensors and controls)

- Flight planning and re-planning

Respecting Airspace Riles and Procedures

- Identifying allowable airspace (potentially defined dynamically)

- Steering to stay in allowable airspace, and performing according to its operating rules

- Stay out of restricted airspace and airspace in which the vehicle cannot meet operating rules

Safe Separation

- Locating the hazards

- Planning and executing maneuvers to avoid them

- Surveillance (technically, locating aircraft within a given airspace)

- Conflict detection and avoidance

- Collision detection and avoidance

Testing and Materials (ASTM), for example, have been working to develop standards (e.g., RTCA Minimum Aviation System Performance Standards [MASPS] and Minimal Operational Performance Standard [MOPS]) that are technology independent. Such standards, when used as a means of compliance with FAA regulations enable multiple means of compliance, thereby supporting innovation. Having said that, much work remains to create the performance-based standards sufficient to cover transformative technologies and operations (e.g., pilot on the ground, pilot controlling more than 1 a/c).

A notable example of the shift from prescriptive to a performance-based standard is for the function of navigation. Early certification standards required aircraft to carry specific systems, such as particular types of navigation radios, which were each certified separately. However, as many different potential systems emerged supporting navigation (e.g., technologies such as Inertial Navigation Systems [INS], long range navigation [LORAN],

and global positioning/navigation satellite systems [GPS/GLONASS] supporting area navigation, rather than depending on routes defined by flight to/from ground navigation radios)—and as computing technologies and algorithms for fusing multiple navigation sensors together created integrated systems more accurate than any one component—FAA and the global air traffic system shifted to certify navigation systems based on their ability to precisely locate the aircraft, with requirements on their accuracy, integrity, reliability, and other safety-critical evaluations of potential failure modes. This provided a shared definition of navigation performance that can be applied to both independent components and integrated aircraft systems, and which refer to outside navigation signals as well as, or instead of, depending on onboard systems. Furthermore, navigation systems now self-monitor their navigation performance, and can flag what performance they are achieving at any instant, including in the face of component failures or gaps in ground/satellite reference signals.

This ability to certify an aircraft’s navigation performance also then dovetails with defining airspace operating rules. Starting in the 1990s, specific air traffic operations, such as instrument approach procedures, could be extended to allow any aircraft meeting its Required Navigation Performance (RNP) standard to execute procedures that previously were not possible. For example:

In 1996, Alaska Airlines flew the first RNP procedure in the terrain challenged environment surrounding Juneau, Alaska. Through the establishment of specific requirements for the execution of radius to fix legs [enabling] … curved procedure segments, which followed the Gastineau Channel, [this airspace procedure provided] a safer and predictable path to the airport. (ICAO, 2019)

As integrated navigation systems became more widespread, many other new operations were defined; unlike historic definitions of operations that required specific technologies distributed between air and ground, these new operations are open to any aircraft demonstrating the RNP.

However, many other functions do not have the same definition of required performance to a degree that allows for transformative changes to technology and operations. Examples of proposed transformative changes for which performance-based standards either do not exist or are only in early stages of development or partially apply include:

- Alternate propulsion and energy-storage and power-generation technologies, including those that use electricity to power the aircraft propulsion (whether created by onboard generators or provided by batteries), hybrid systems that use two different types of

- Alternate vehicle configurations involving multiple rotors, in some cases also supplemented by lifting surfaces that themselves may be tilted or freely rotating.

- Airspace and air traffic functions performed by different technologies than those assumed in the operating rules, such as those assuming the vision of an onboard human pilot as the primary mechanism for detecting other aircraft and/or for detecting the runway during approach and landing.

- The shift of any aspect of the “Aircraft Functions” from being performed onboard the aircraft to being performed by some combination on onboard autonomous technologies and a pilot located on-the ground and beyond visual line of sight, or by a third-party service provider.15

propulsion power (e.g., electric for cruise, supplemented by gas for climb), and radically new fuel types such as hydrogen.

These efforts show the challenge, and the potential, of expanding performance-based standards for certification and operational approval, but they are also notable for being limited to isolated cases. A more pervasive and comprehensive development of performance-based standards could enable a much wider range of innovations in technology and operations.

To illustrate how performance-based standards may be developed by FAA alone or by industry-wide committees, RTCA minimum performance standards begin with an Operational Services and Environment Definition (OSED). As new entrants with unique concepts of operation, such as UASs emerged, RTCA (2022) published an OSED to guide its development of Detect and Avoid (DAA) standards for these remotely piloted systems. The purpose of this OSED was to provide a basis for assessing and establishing operational, safety, performance, and interoperability requirements for DAA systems.

As even more innovative technologies and operational concepts are developed, it will become necessary to develop more performance standards accommodating how they perform the critical functions noted in Box 2-1 in innovative ways. These will require OSED-like documents to identify all assumptions that could affect safety for both the applicant and all those potentially impacted by them in the airspace. For example, to certify operations in which one ground pilot could be remotely piloting multiple aircraft,

___________________

15 One industry participant in the committee’s workshops perceived that, at this time, there is no standard for certifying the ground control station for remotely operating an autonomous midsize cargo aircraft. If such a standard is based on component technologies, it would be difficult to establish without limiting it to particular specifications of which functions are performed remotely by the pilot or ground-based technology and which are performed automatically onboard the aircraft.

all such characteristics of the operation and the airspace in which it intends to operate, and the airports or landing sites from which it intends to takeoff or land, must be spelled out, and safety requirements must be allocated to each component of the operation. In this example, standards will need to capture all aspects of these operations in a manner that allows for a range distribution of technology-specific implementations of what people and systems collectively perform the function, including a range of possible variants between what occurs onboard the aircraft and what is executed on the ground, and a range of autonomous functions between minimal pilot support to fully autonomous functions. Only this level of detail will allow for the necessary detailed examination of the skills the personnel will need and confirmation these personnel have appropriate workload, information, and control authority. and a commensurate detailed specification of the behaviors required from technologies both onboard the aircraft and on the ground.

Finding 2-3: Current standards for certification and operational approval for many functions necessary for safe flight prescribe technologies, roles, and skills for personnel, and operating rules that assume historic concepts of operations and architectures. These assumptions do not fit with, and can conflict with, proposed transformative changes to aviation technology and operations. Instead, performance-based standards can direct assessments of how well a proposed technology or operation meets safety standards and do so in a manner directly supporting certification and operational approval.

Recommendation 2-3: The Federal Aviation Administration Office of Aviation Safety should lead the definition of performance-based standards for flight-critical functions that allow for different equipage, different methods of performing the functions, and a different distribution of who or what is performing the functions’ constituent activities, including changes in distribution of activity between human or machine, on the aircraft or on the ground, by the operator (e.g., airline), air traffic or a third party. These performance-based standards should be developed to the point that they can serve as a basis for certification and for approving new operations within the National Airspace System.

CHANGES TO GENERAL OPERATING AND FLIGHT RULES

The committee recognized that a central feature of many transformative changes is the applicants’ need for changes to general operating and flight rules governing how aircraft operate in the NAS. For example, some proposed aircraft for very short air taxi flights or last-mile airborne cargo

delivery may not operate out of current airports and may never reach the altitudes at which most air traffic control functions are invoked. Others, such as supersonic or high-altitude long-endurance aircraft, may cruise at high altitudes but require very different speeds and climb/descent rates to get there.

Where they cannot meet the specifications defined in 14 CFR Part 93 or Part 107, they will require exceptions to current general operating and flight rules or generation of new operating rules. Unlike certification of individual systems or entities, these operating rules must also address concerns of all stakeholders impacted by the new operations. Short, low air taxi and cargo delivery flights, for example, may need low altitudes and routes of flight over urban areas that interact with low-level medevac and law enforcement helicopter operations and that must address community concerns with noise, privacy, and safety of sensitive locations on the ground.

These operating and flight rules can be central to a holistic assurance of safety in that they can help define the performance-based standards for what the technology and the personnel need to do. However, as noted earlier in this chapter, there is a long history of having technologies certified but then a lengthy delay until their commensurate new operations are approved.

Unfortunately, while engineering methods exist for failure-assessment of technology in support of technology certification, there is no equivalent systematic, rigorous, broadly documented method for assessing novel operating and flight rules. Thus, while the certification path has (to varying degrees) some definition that an applicant can use to predict timeline, test and evaluation requirements, and so on, there is no clear path to operational approval. As noted earlier and characterized in an example in Appendix A, operational approval can require many changes throughout the NAS.

At this time, these challenges are being addressed by examining proposed changes each on a case-by-case basis. For example, a recent Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) examining Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) UAS operations,16 and an RTCA forum on Digital Flight Rules, each advocated for specific changes in operating rules.17 These exemplars illustrate the careful and detailed attention required for changes to operating rules, and the significant number of stakeholders and types of analyses that are necessary to evaluate changes to operating rules. Of note, in the absence of an established framework and methods for analyzing operating rules, these studies each approached their task in different ways, and needed to develop metrics and methods from first principles.

___________________

16 See https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/rulemaking/committees/documents/index.cfm/document/information/documentID/5424.

Furthermore, different operators cannot create competing operating rules. For example, if several advanced air mobility (AAM) applicants and commercial drone package delivery services each propose their own preferred operating rules independently, they can’t all be approved simultaneously if they might in any way conflict or obstruct each other (e.g., differing assumptions of how to define low-level air routes or safe operating zones or altitudes). Likewise, unless there is some mechanism for ensuring new types of operations are decoupled (commonly described as “segregated”) from current operations, they must be made interoperable and not adversely impact others in the airspace.

Finding 2-4: Radical transformations to general operating and flight rules are being proposed, or will be necessary, to safely operate proposed vehicles. However, there are no systematic, rigorous, broadly documented methods for identifying, categorizing, and analyzing the risks that may emerge with novel operating and flight rules, especially where the changes are sufficiently transformative that they cannot be predicted via extrapolations from the present day.

Recommendation 2-4: Congress should ensure that fundamental and generalizable research is chartered to establish a systematic and repeatable framework for analyzing and designing civil aviation general operating and flight rules that enable novel technologies and operations to share the airspace with current operations. This requires fundamental and generalizable research beyond the Federal Aviation Administration’s current research expertise and portfolio, and may need the support of other agencies conducting fundamental research into operational system-wide safety. These methods must calculate the appropriate performance requirements for all the functions noted earlier, be able to identify and characterize safety concerns created or mitigated by the operating and flight rules, and be detailed enough to articulate the specific activities, and required information needs and control authority, of all actors and stakeholders and how these activities combine to create safe operations.

Finding 2-5: Different aircraft operators cannot use conflicting general operating and flight rules in the same airspace, highlighting that these flight rules cannot be developed independently by individual applicants, but must have some guiding structure and constraints that is fair to all in terms of access to the airspace and safety for all in the airspace while minimizing undue constraints on innovation.

Recommendation 2-5: The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the aviation industry should develop a process for defining the general operating and flight rules that enable new, innovative operations to coexist in the airspace with other innovative operations as well as legacy operations. FAA should launch a single-purpose group (e.g., task force, aviation rule making committee) including representatives of all relevant stakeholders from legacy and new operations for the purpose of identifying the fundamental structure of and constraints on operating and flight rules for broad classes of current and proposed new operators in the National Airspace System. This should include consensus-based recommendations for development of technical standards that characterize all relevant aspects of the proposed operations relevant to assessing their safety and that identify the essential constraints on and performance measures of new operating rules needed to address potential risks emerging from changes in the operations.

REFERENCES

14 CFR §11.19. n.d. What is a special condition? https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-11/section-11.19 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR §11.71. n.d. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2024-title14-vol1/pdf/CFR-2024-title14-vol1-sec11-71.pdf (accessed June 5, 2024).

14 CFR §25.1303. n.d. Flight and navigation instruments. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-25/section-25.1303 (accessed June 5, 2024).

14 CFR §91.175. n.d. Takeoff and landing under IFR. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-91/section-91.175 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Chapter I. n.d. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Chapter I Subchapter C Aircraft. n.d. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/chapter-I/subchapter-C (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Part 21. n.d. Certification procedures for products and articles. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-21 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Part 61. n.d. Certification: Pilots, flight instructors, and ground instructors. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-61 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Part 63. n.d. Certification: Flight crewmembers other than pilots. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-63 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Part 65. n.d. Certification: Airmen other than flight crewmembers. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-65 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Part 67. n.d. Medical standards and certification. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-67 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Part 91. n.d. General operating and flight rules. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-91 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Part 107. n.d. Small unmanned aircraft systems. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-107 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Part 121. n.d. Operating requirements: Domestic, flag, and supplemental operations. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-121 (accessed June 3, 2024).

14 CFR Part 135. n.d. Operating requirements: Commuter and on demand operations and rules governing persons on board such aircraft. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-14/part-135 (accessed June 3, 2024).

Baker, A. 2017. These American drones are saving lives in Rwanda. TIME.com (blog). https://time.com/rwanda-drones-zipline.

Clouse, M. 2024. AFWERX Autonomy Prime Partners Demonstrate Autonomous Flight Capabilities, Make History At. One AFRL – One Fight. https://www.afrl.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/3669627/afwerx-autonomy-prime-partners-demonstrate-autonomous-flight-capabilities-make.

FAA (Federal Aviation Administration). 2001. Federal Register. 66. Vol. 117. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2001-06-18/pdf/01-15333.pdf.

FAA. 2005. Air traffic technical training. Order 3120.4L. https://www.faa.gov/documentlibrary/media/order/nd/3120-4l.pdf.

FAA. 2010. Enhanced flight vision systems. Advisory Circular 90-106. https://www.faa.gov/documentlibrary/media/advisory_circular/AC%2090-106.pdf.

FAA. 2012. Expanding use of small unmanned aircraft systems in the Arctic, Implementation Plan, FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012. U.S. Department of Transportation.

FAA. 2016. Summary of small unmanned aircraft rule (Part 107). FAA News. https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/uas/resources/policy_library/Part_107_Summary.pdf.

FAA. 2017. Advisory Circular AC No: 90-106A: Enhanced Flight Vision Systems. U.S. Department of Transportation.

FAA. 2018. United States Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS). Vol. 8260.3D. https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Order/Order_8260.3D_vs3.pdf.

FAA. n.d.a. Completed Programs and Partnerships. https://www.faa.gov/uas/programs_partnerships/completed#uoa (accessed June 5, 2024).

FAA. n.d.b. Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM). https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/aim_html (accessed June 3, 2024).

FAA. n.d.c. Air traffic control. Order JO 7110.65AA. https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/atc_html (accessed June 3, 2024).

FAA. n.d.d. Part 107 waivers issued. https://www.faa.gov/uas/commercial_operators/part_107_waivers/waivers_issued (accessed June 5, 2024).

FAA. n.d.e. Petition for exemption or rulemaking. https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/rulemaking/petition (accessed June 5, 2024).

FAA. n.d.f. Unmanned aircraft systems (UAS). https://www.faa.gov/uas (accessed June 5, 2024).

FEDweek. 2013. FAA authorizes drone use to help fight Yosemite fire. FEDweek, September 11. https://www.fedweek.com/federal-managers-daily-report/faa-authorizes-drone-use-to-help-fight-yosemite-fire.

ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization). 2019. ICAO Working Paper A40-WP/173. Efficiency in air traffic management through required navigation performance authorization required (RNP AR). Vol. 40th Session. ICAO. https://www.icao.int/Meetings/a40/Documents/WP/wp_173_en.pdf.

Parady, C. 2023. TSO 101. Presented at the TSO Workshop, September 20. https://www.faa.gov/aircraft/air_cert/design_approvals/dah/tso101.

RCTA. 2022. DO-398A Operational Services and Environment Definition (OSED) for Uncrewed Aircraft Systems Detect and Avoid Systems (DAA).

RTCA. n.d. Standards oversight committee acts on emerging technologies and safety oversight. RTCA (blog). https://www.rtca.org/news/6937-2 (accessed June 5, 2024).

“Revisions to Operational Requirements for the Use of Enhanced Flight Vision Systems (EFVS) and to Pilot Compartment View Requirements for Vision Systems.” 2016. Federal Register. December 13, 2016. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/12/13/2016-28714/revisions-to-operational-requirements-for-the-use-of-enhanced-flight-vision-systems-efvs-and-to.

Safran Electric & Power S.A. 2024. Special Conditions (Proposed) 33-23-01-SC. FAA-2023-0587. https://drs.faa.gov/browse/excelExternalWindow/FR-SCPROPOSED-2024-05101-0000000.0001?modalOpened=true (accessed June 3, 2024).

San Antonio Air Charter. 2022. FAA Exemption Request 19138. FAA-2021-0489. https://drs.faa.gov/browse/excelExternalWindow/FAA0000000000000000000000EX19138.0001?modalOpened=true.OversightEmergingSafetySmallAircraft.