Aging in Place with Dementia: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 4 Evaluating Successful Programs

For the third session of the workshop, speakers explored how to measure and evaluate programs and other interventions for people with dementia aging in place. Speakers and workshop participants had been asked to consider the following questions: To what extent should the goals of programs that support aging in place with dementia be targeted to keep people in their own homes versus in a community or social environment that might better suit their needs? Can aging in place for people living with dementia be evaluated in terms of improvements in quality of life, deferred transitions to facility-based care, or other metrics?

AN INTERVENTIONIST’S PERSPECTIVE

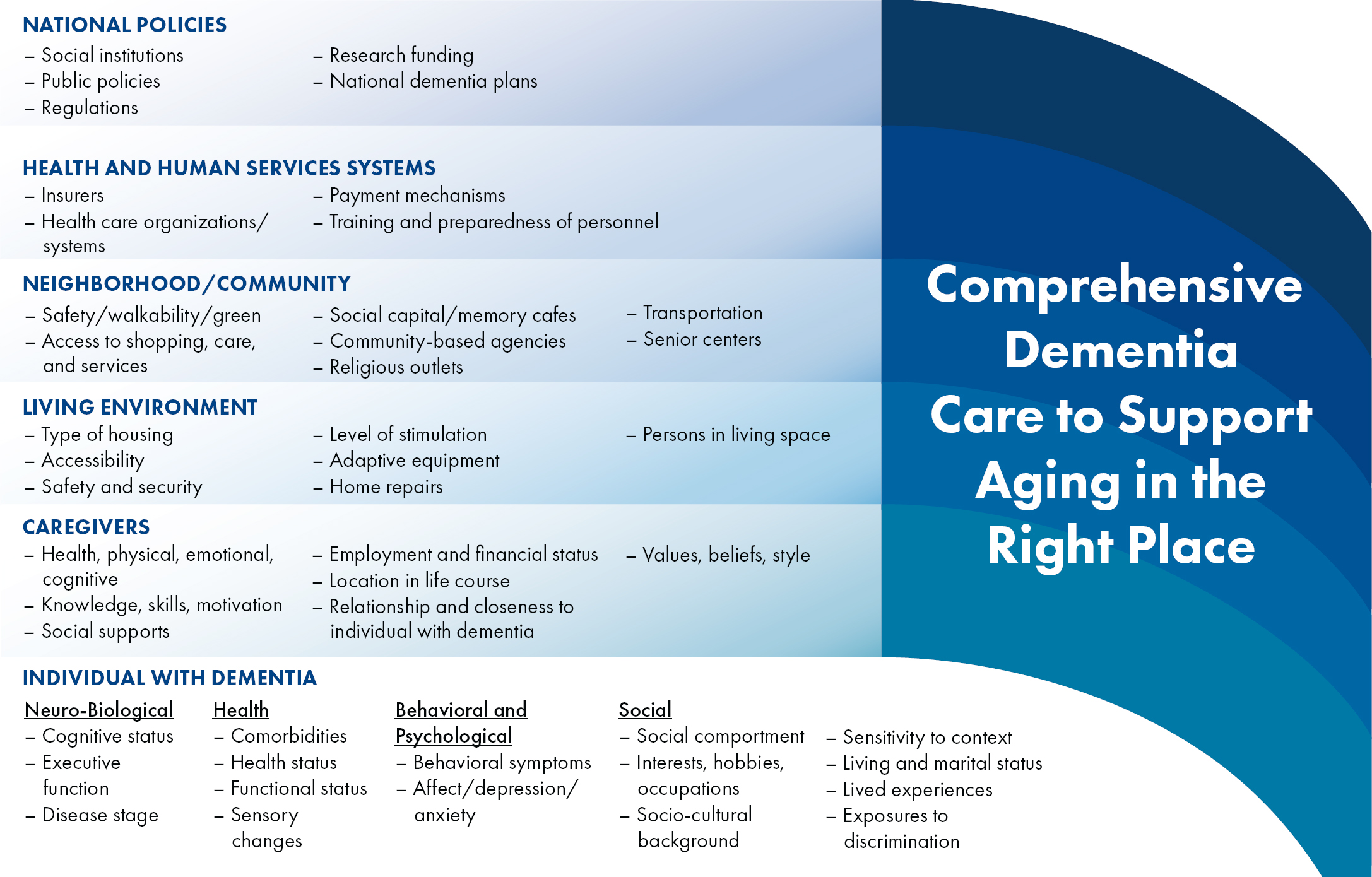

Laura Gitlin (Distinguished Professor and Dean Emeritus, College of Nursing and Health Professions, Drexel University) asserted that comprehensive dementia care is needed to support people aging in the right place, and she presented a socio-ecological model for guiding appropriate interventions (Gitlin & Hodgson, 2018). Constructing these multilevel, complex interventions to enable aging in the right place and to improve well-being requires consideration of individual-level neurobiological, behavioral, health, and social factors; an understanding of the “right place” in relation to how it affects family members and other caregivers; awareness of different kinds of living environments and related issues of accessibility, safety, maintenance, and stimulation; consideration of community-level services and supports; participation of health and human services systems (including Medicaid-funded home- and community-based services and adult day services); and implementation of national policies: see Figure 4-1.

Gitlin indicated that because dementia is a progressive disease, a person’s needs will change with each new stage. Thus, the right place for aging may change as the disease progresses, which creates additional challenges. She emphasized that this concept of aging in place has not been well defined in the past 50 years of dementia care research, which primarily developed interventions to address the clinical symptoms of dementia, as well as more than 200 types of interventions to provide support, knowledge, and strategies to family caregivers. However, she noted, the emerging research considers more complex interventions through a health equity lens. Instead of only targeting individuals and their caregivers, these interventions help create a knowledgeable workforce in community-based services (e.g., at the agency level and for home modifications) to better support those individuals and their families.

Gitlin shared the following lessons learned from hundreds of clinical trials targeting individuals or caregivers, which could be useful as the next generation of interventions is designed:

- Supportive programs for caregivers are highly effective at addressing psychosocial outcomes, but evidence of the effectiveness

- of programs targeting only the people living with dementia is inconsistent.

- Interventions are most successful when they are multicomponent—combining counseling, support, education, stress, mood, management, and skills training—and when they are tailored to the specific needs of either the individual living with dementia or the caregiver. Which groups benefit most from these interventions remains unclear because samples underrepresent racial, cultural, linguistic, ethnic, and geographic diversity.

- Most programs and their outcomes focus on mood, stress, health, quality of life, management of clinical symptoms, nursing home placement, and health utilization, but no single program is effective for all desired outcomes.

- The benefits of aging in place for the person’s family unit are unclear. Relocation is typically due to a need for 24/7 supervision, mobility changes, and particular care and medical needs. Housing stock and housing repair needs are also unclear.

- Goals for aging at home should be balanced with family responsibilities and burdens, but the needs for people living alone are unclear.

Gitlin next described outcomes relevant to aging in place from the Tailored Activity Program, which supports individuals living with dementia, and the Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment (COPE) Program, which also supports the family caregivers (Clemson et al., 2021; Gitlin et al., 2010, 2021; Fortinsky et al., 2020; Pizzi et al., 2022). For example, caregivers who participated in the COPE Program were less upset and had higher confidence, and people living with dementia had fewer behavioral symptoms, reduced physical dependencies, and enhanced engagement. She asserted that improving well-being for caregivers is essential to enable aging in place for people living with dementia. Such interventions also increase home safety and save money for health systems. In the Tailored Activity Program, nearly 50% improvement was observed in health-related events that often trigger relocation for people living with dementia, and there was a reduction of more than 60% in the number of hospitalizations for program caregivers (Gitlin et al., 2021). In a COPE Program intervention that integrated an activity approach with caregiver support over a 4-month and a 9-month period, caregivers reported improved quality of life for the person with dementia, helping to keep that person living at home (Gitlin et al., 2010).

Gitlin shared additional data from a study on the use of the Adult Day Service Plus Program1 over a 12-month period, which also showed an in-

___________________

1 According to Alzheimers.gov, this program includes five components: care management, resource referrals, dementia education, situational counseling with emotional support and stress reduction techniques, and skills to manage behavioral symptoms (e.g., rejection of care, agitation, aggression).

crease in confidence and well-being among caregivers, as well as a decrease in depression (Gitlin et al., 2006, 2023; Reever et al., 2004). She explained that by increasing the ability of adult day service staff to provide evidence-based support for family caregivers, the families’ ability to use adult day service increased and nursing home placement decreased by 50%. This study demonstrates that adult day services play a critical role in enabling aging in place for people with dementia. She pointed out that these outcomes were particularly important for Black caregivers in the study, who missed fewer of their own medical appointments by using the adult day service for those for whom they provide care.

Gitlin presented the results of another important study, which compared four interventions (Maximizing Independence at Home, New York University Caregiver, Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care, and Adult Day Service Plus) to usual care. Results indicated that the interventions reduced nursing home admission, improved people’s quality of life, increased cost savings for the community, increased time for people to spend in the community, provided more effective care, and reduced cost for delivery of care (Jutkowitz et al., 2023). She underscored that although these interventions share certain principles, they differ, which reinforces the notion that there will never be one single approach to meet all of the needs of both people living with dementia and their families.

In closing, Gitlin offered recommendations for four areas of research. First, new approaches to intervention development that involve interested parties (e.g., people living with dementia, caregivers, other family members, other stakeholders) and that use community participatory processes are needed. Mixed-methods research would help to understand feasibility, acceptability, effectiveness, and implementation outcomes of interventions for diverse individuals and communities. She underscored that researchers should consider context, delivery, sustainment, training, and cost from the start of intervention development, as well as considerations of equity at each methodological decision point. Additional research on the benefits of theory- and mechanism-based interventions would also be beneficial. She stressed that multilevel interventions, which add complexity but may reduce health disparities, should be prioritized. New interventions to support people with dementia who live alone, to offset responsibilities of family caregivers, to address a broader range of needs at different disease stages, to examine dyadic relationships, and to examine informal networks for decision making are also needed (Gitlin & Czaja, 2016).

Second, she said that new or adapted frameworks are needed to understand the meaning of and ability to age in the right place with dementia, such as expanded models to address the unique lived experience and the range of clinical symptoms of dementia that are triggers for relocation; expanded or adapted models to address the needs of family members and

long-distance caregivers; models for people living alone; and theories and models to understand the impact of relocations for the individual and family members.

Third, she advocated for aligning outcome measures with stakeholder values; using targeted measurement strategies to reflect what matters most to families; and developing complex, multilevel metrics, including individual, family and caregiver, home environment, and community.

Finally, in terms of implementation, she suggested adopting new methodologies to move evidence more rapidly to practice so that more individuals and their families can benefit from interventions. She cautioned that many implementation challenges remain, including those related to payment models, regulatory issues, staffing availability, workflow alignment, and housing stock. As interventions move to the real world, evaluating implementation outcomes—such as acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, cost, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability—will be critical (Proctor et al., 2011).

ADOPTING A HOUSING LENS

Jennifer Molinsky (Project Director of the Housing an Aging Society Program, Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University) suggested that in addition to being viewed through medical and public health lenses, aging in place for people with dementia should be considered through a “housing lens”—that is, recognizing that where people live shapes challenges and limits solutions. Enabling aging in place for people with dementia requires understanding the complex interplay of housing as a home, as a site of care, as a financial burden, and as a physical environment. However, she explained, barriers to creating robust and effective interventions often arise because housing and health interventions emerge from different fields of research and are supported by different federal programs.

Although “aging in place” is interpreted differently by different people, Molinsky continued, definitions are rarely established in research or policy discussions. For example, for some people, aging in place means never leaving their homes; for others, it means staying in their homes only as long as possible. Additional definitions of aging in place include aging in a particular community, avoiding a nursing home, not moving between aged care facilities, or having choices about where to live. She pointed out that these differences have important implications for research, policy, and intervention (Forsyth & Molinsky, 2021; Molinsky & Forsyth, 2018; see Table 4-1). Furthermore, questions remain about individuals’ actual preferences about where they would like to age, which are difficult to study and measure. She proposed adopting Gitlin’s terminology of “aging in the

TABLE 4-1 Definitions of Aging in Place by Context

| Definitions: Older people should/can: | Common rationales and/or motivations | Examples of policy implications | Examples of policy implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place-related | |||

|

Apparent simplicity of not moving, familiarity of environment, cost savings from not moving | Modify and service existing homes | Overhousing of older people, limiting supply; problems modifying housing; difficulties providing services; cost of in-home services at end of life; stuck in place |

|

Simplicity, along with options late in life | Provide options for high care at end of life | If only the very ill are in purpose-built housing and nursing homes, then there could be concentrations of only the very sick in facilities; different understandings of as long as possible within household/family |

|

Allows downsizing/rightsizing but maintaining familiarity of area | Provide housing options nearby | Options may not be available or may be more costly |

| Services based | |||

|

Can be anywhere, including with distant family | Flexible care options outside facilities; making nursing homes less repulsive | Inefficiency, lower quality care, household strain |

|

Not moving within care facility | Flexible care options in facilities | Regulatory barriers, staff training |

| Definitions: Older people should/can: | Common rationales and/or motivations | Examples of policy implications | Examples of policy implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | |||

|

Self-determination | Individual housing options | Moving may be a better option |

|

User choice, government cost savings | Provide housing options including upgrading; age-friendly communities | Moving may be a better option for fit |

SOURCE: Forsyth & Molinsky (2021, Table 1). Reprinted with permission.

right place” or even “living in the right place,” which highlights the benefits of aging instead of the degenerative process.

Molinsky noted that a housing lens provides insight because it centers on the complexities of where people live. Home is perceived as a platform for well-being based on its affordability, its physical suitability, its connections to supports and services, and its potential to contain memories and bolster one’s sense of self. A housing lens also reveals housing disparities among older adults, such as unstable, inadequate, unaffordable, or inaccessible housing, as well as a lack of nearby caregivers or community supports. Finally, she indicated that a housing lens acknowledges that home-focused interventions depend on a home’s stability, its resources, and its capacity to function as a site of care and a site of employment for both care providers and unpaid family members (Molinsky et al., 2022).

Applying this housing lens, Molinsky commented that older adults have unique housing challenges that affect their health. For example, although a lack of affordable housing affects everyone, it is more prevalent among older adults. Eleven million households in the United States use more than 30% of their income for housing, and more than five million households use more than 50% of their income for housing. She stressed that cost burdens are more prevalent among people of color; renters who have little control over their housing costs because of fixed resources (e.g., typical renters ages 65 and older have less than $6,000 in total net wealth); and owners with mortgages, which is the case for 27% of adults aged 80 and older (see Federal Reserve Board, 2019; U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). The gap between Black and White homeownership in particular is at a 30-year high among older adults, which affects the availability of resources to pay for care. These lifetime disadvantages compound in older age, widening disparities in health and financial security. People whose housing costs consume most of their resources have little to spend on other necessities, such as food, health care, transportation, and medication (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2018). Yet, she noted, only one-third of older, low-income households who are eligible for housing assistance actually receive resources.

Furthermore, even though accessibility needs increase with age and an increasing number of older adults experience difficulties using and navigating their homes, Molinsky reported that less than 1% of all U.S. housing is fully wheelchair accessible, and only 3.5% offers basic accessibility features (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2011, 2019). This lack of accessibility increases the risk for injury and increases the need to rely on others for assistance with activities of daily living. She added that caregivers are also an integral part of the residential setting to enable aging in place (Molinsky et al., 2023), yet they too may be experiencing stress related to increasing housing costs or decreasing housing quality.

Molinsky underscored that aging in place requires more than affordable and accessible housing; many older adults need in-home support for household tasks and self-care, which is expensive and difficult to obtain. An increasing number of older adults are living in low-density areas, which may be difficult to reach for service providers. Loneliness is also a health risk, she noted, but many older people have a difficult time navigating spaces outside their homes and having access to transportation in their communities. Older people are also susceptible to weather-related risks, such as extreme heat or disruptions in health care after a storm. She noted that strategies to address some of these deficiencies in the current housing stock as well as to monitor and deliver better care in the home through technology, are being explored, but more research is needed into the disparities related to access to broadband, inaccessible housing, and housing insecurity that exclude people from these opportunities.

Molinsky also identified challenges in the coordination among housing, social services, and health care sectors needed to enable aging in place for people with dementia. For example, eligibility for subsidies differs across housing and service programs, leaving some people without critical supports. Furthermore, programs that make housing healthier and safer do not necessarily result in cost savings. Thus, additional research that investigates the health outcomes of housing or home-based interventions would be beneficial. Another significant challenge is a lack of data integration. For example, data on housing typically lack sufficient information on health, and health data typically lack sufficient details on housing. She cautioned against relying on data that focus on health care utilization, which could emphasize research questions based on cost savings rather than overall wellbeing or health (Molinsky et al., 2022).

Molinsky offered two concluding thoughts. First, using a housing lens to focus on older adults’ homes in relation to their health and wellbeing (including financial security, social engagement, physical safety, and access to services and supports) serves as a reminder that older adults are more than their illnesses or clinical experiences. This perspective also helps illuminate the economics of aging in the United States, including the “dual burden” often posed by both housing and care costs. She asserted that considering where people live might change the way issues of aging in place are addressed.

Second, Molinsky said, increased dialogue between housing and health researchers could help illuminate the specific ways that housing influences health for people with dementia, support the development or integration of datasets that enable evaluation of housing-based interventions for health, highlight how disparities in housing affect the outcomes of other interventions, and support outcome measures beyond those focused on health care utilization (Molinsky et al., 2022).

EVALUATION: TOWARD A VALUE PROPOSITION

Louise Lafortune (Principal Research Associate, Cambridge Public Health, Cambridge University) observed that “home” is embedded in interconnected community, social, and policy environments, and the aging experience can be successful only to the extent that these environments enable such an outcome. She argued that programs that support aging in place both for people with and without dementia should optimize the fit between individuals and their living environments. However, she pointed out that the evidence base on what works, for whom, and under what circumstances is limited, creating barriers to implement and scale interventions.

Lafortune asserted that a successful later life is possible at all stages of health and frailty if supports are well targeted and delivered equitably: that is, by understanding the factors that influence successful aging, developing interventions and solutions that are tailored to people’s needs, and demonstrating what works and adds value. Although evaluation efforts of interventions at the individual level are increasing and evidence is accumulating, the evidence for interventions that target dyads, social networks, cities, and policies is lacking.

Using the framework from the World Health Organization for age-friendly cities and communities, Lafortune discussed how capacity is being built for such evaluations. Age-friendly cities and communities leverage an approach in which policies, services, settings, and structures support and enable people to age actively (World Health Organization, n.d.). These communities “are created by removing physical and social barriers and implementing policies, systems, services, products and technologies that address the social determinants of healthy aging, and enable people, even when they lose capacity, to continue to do the things they value” (United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing, n.d., p. 13). Much has been invested in these communities, but further research is needed to better understand how and if they are effective.

Lafortune emphasized that because there will never be enough funding to evaluate all that needs to be evaluated, her team is building capacity for evaluation by providing the practice-focused tools and the understanding of the process for evaluating complex interventions. The first step in building this capacity was creating a survey to understand the needs of members of the U.K. network of age-friendly communities, which highlighted a lack of capacity for evaluation in practice. However, to sustain investment in age-friendly initiatives, demonstrating their impact is critical. Thus, her team developed a process evaluation tool in collaboration with practice stakeholders that identifies and assesses the “active ingredients” of a sustainable age-friendly community. The tool included ten evidence input areas to guide information collection: political support; leadership and governance; finan-

cial and human resources; involvement of older people; priorities based on needs assessment; application of existing frameworks for assessing age-friendliness; provision; interventions rooted in evidence base; coordination, collaboration, and interlinkages; and monitoring and evaluation (Buckner et al., 2018; Buckner, Pope et al., 2019). She explained that this evaluation tool for age-friendly communities was piloted for an intervention in Liverpool, in a dementia-friendly community in Sheffield, and to inform the creation of a new community in Northstowe. The tool used a scale of 1–5 to determine whether enough evidence exists in each area to assess both the process and the progress of the age-friendly communities. In one instance, the tool revealed that despite political support, leadership and governance were lacking, which made it difficult to monitor progress and implement the right types of interventions.

After this pilot experience, Lafortune and her team became involved in a national evaluation of dementia-friendly communities in England called the DEMCOM study.2 Providing context on this effort, she noted that in 2015, the Prime Minister’s Challenge set a target to have more than half of England’s population living in areas recognized as dementia-friendly communities by 2020. She noted that these communities, guided and officially recognized by the Alzheimer’s Society, vary by size and shape, but the common goal is to ensure that people affected by dementia can continue to be active and to be valued citizens. The DEMCOM study attempted to better understand the characteristics and areas of focus of dementia-friendly communities, how different types of communities enable people affected by dementia to live well, what is needed to sustain the communities, what value the communities generate, and how the communities can be assessed.

Lafortune and the DEMCON team piloted the evaluation tool developed for age-friendly communities in two dementia-friendly communities, conducted a survey among national stakeholders, and developed a revised evaluation framework better suited to evaluate dementia-friendly communities and to guide evaluators’ work. The revised framework included thematic domains—activities and environments, basis of dementia-friendly community, leadership and governance, resources, and monitoring and evaluation—and crosscutting issues—evolution, equalities, and involvement of people affected by dementia (Buckner et al., 2022; Buckner, Darlington et al., 2019; Darlington et al., 2020; Mathie et al., 2022; Woodward et al., 2019). A suite of evaluation resources for dementia-friendly communities that accompanies the framework includes a theory of change tool (i.e., how dementia-friendly communities can make a difference and what outcomes

___________________

2 https://arc-eoe.nihr.ac.uk/research-implementation/research-themes/ageing-and-multi-morbidity/demcom-study-national-evaluation

they can achieve at what stage) and a matrix for assessing community maturity (which can inform community aspirations; Buckner et al., 2022).

Lafortune also provided an economic perspective on dementia-friendly communities, describing efforts from the DEMCOM study to implement simple tools to better understand the resources that drive these communities. Increased awareness of these resources makes it possible to inform decision making for investments and sustain key activities in dementia-friendly communities. Using an approach known as social return on investment (i.e., an approach building on cost-benefit analysis) and data derived from DEMCOM to explore the social value of dementia-friendly communities for people with dementia, she and her team found that dementia-friendly communities have the potential to generate a significant social return on investment.

For age-friendly community initiatives in particular, however, Lafortune noted that little is known about short- and long-term benefits and resource implications. She described current efforts to understand the health-related outcomes of age-friendly community interventions and their social value for older adults, as well as the resources needed to sustain these complex interventions at different geographical scales. Preliminary evidence from a systematic review suggests that aging-well interventions, including those targeting people with dementia, generate a positive social return on investment.3 The next step is to explore how that information can be used in practice to support implementation.

In closing, Lafortune offered suggestions for future work. She encouraged the formation of interdisciplinary research programs to create the knowledge to understand the mechanism of action of complex interventions, their impact on phenotypes of aging in context, and barriers to the implementation of research findings. She also proposed that evaluations embrace the complexity of aging in place for people with dementia by engaging older adults and practice stakeholders from the design to the implementation of evaluation, developing a theory of change to guide impact assessment, and tailoring research questions and methods to the maturity of the intervention. She noted that economic and social value implications need to be better understood to help implement and sustain aging in place initiatives. Lastly, she encouraged researchers to embrace an equity lens to avoid intervention-generated inequalities.4

___________________

3 An overview of the review can be found at: https://arc-eoe.nihr.ac.uk/research-implementation/research-themes/population-evidence-and-data-science/evidencing-social

DISCUSSION

Sharing questions from workshop participants, Jennifer Ailshire (Associate Professor of Gerontology and Sociology, Assistant Dean of Research, and Associate Dean of International Programs and Global Initiatives, University of Southern California; planning committee member) moderated a discussion among the session’s three speakers. She highlighted the speakers’ points about the costs and benefits of interventions, strategies to reduce future costs, and renewed concepts of aging in place that are determined by the least financial hardship. She invited the speakers to share any additional commentary on issues of cost and aging in place.

Lafortune emphasized the importance of understanding both the costs related to people’s living conditions and the costs of interventions. She explained that the effects of an aging in place intervention on the utilization of health care services can be measured relatively easily as long as people recognize that this is an outcome to support the sustainability of the intervention. An intervention can be deemed “cost-effective” when additional health benefits accrue from investing in that particular intervention. However, she pointed out, the budget implications of rolling out an intervention are often not captured in these analyses. Thus, unless an evaluation program captures the effects of the intervention on health outcomes, as well as the consequence of maintaining people in that state of health, funders may not understand why they should invest in an intervention.

Gitlin noted that defining cost is important, especially because decreasing societal financial cost could increase family caregiver financial cost. Furthermore, because U.S. systems are fragmented, even when community-based programs help people to remain living at home and reduce health care utilization, they do not share in the cost savings that benefit the health care systems. Evaluating complex financial elements is critical, she continued, owing to different implications for different people.

Emily Agree (Research Professor and Associate Director, Hopkins Population Center, Johns Hopkins University; planning committee chair) wondered whether any financial and housing problems could be addressed if Medicaid paid for assisted living. In response, Molinsky underscored that assisted living is not accessible for most people in the United States because they cannot afford to pay for it out of pocket and do not qualify for a subsidy. She urged researchers to explore how to better support low-income people, as well as how supporting housing and care together could improve this situation. Gitlin agreed that finances are a significant issue for families, especially when thinking about living situations, and they would benefit from increased guidance about and awareness of alternative options for care.

Ailshire pointed out that sometimes institutionalized care may be the best outcome for people with dementia and their caregivers. She asked about studies that compare quality of life outcomes and life expectancy for those aging in a nursing home versus those aging at home. Lafortune replied that comparing quality of life in these two different settings is difficult: people in nursing homes tend to be more advanced in the disease than people living at home, which complicates the potential for a direct comparison. Molinsky agreed and noted that comparisons about quality of life often include a self-selection problem. Although quality of life is an important issue, she continued, much of the current evidence is only anecdotal; data to evaluate the true value of different settings in which people age are needed.

Gitlin raised the issue that extreme variability in care exists across facilities, and no known databases help address this problem. Elena Fazio (Director of the Office of Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias Strategic Coordination, Division of Behavioral and Social Research, National Institute on Aging [NIA]) mentioned that the National Health and Aging Trends Study follows individuals from setting to setting, providing a robust data resource for researchers in the United States interested in studying quality of life across settings. However, she said that more data that follow people across settings are needed, especially given the complexity of meaningfully defining and measuring quality of life.

Reflecting on Ailshire’s and others’ comments that aging at home may not be optimal for several reasons, Lis Nielsen (NIA) posed a question about whether deferring transition to facility-based care should still be a primary goal or if researchers should also consider an agenda around how people can age well in place in appropriate facility-based environments. Molinsky championed the value of considering multiple settings in discussions on aging in place and indicated that robust data are needed to evaluate components of both health and home, such as cost, accessibility, and interconnectedness with other community services.

Nielsen then asked how to better prepare employees at community sites, volunteers, and professional care staff to support people living with dementia to age in place. Lafortune said that in the United Kingdom, the Alzheimer’s Society developed the Dementia Friends Program,5 which trains people in different communities using a “train the trainers” approach. For example, in one of her dementia-friendly community case studies, one grocery store employee was trained to train his employees to recognize signs of dementia in shoppers. Regina Shih (Professor of Epidemiology and Health Policy and Management, Emory University, and Adjunct Policy researcher, RAND)

___________________

5 The program is an initiative of the Alzheimer’s Society; https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-involved/dementia-friendly-communities/dementia-friends

noted that a few villages in the Village to Village Network are beginning to train their staff using the AARP Dementia-Friendly Communities Program.6 Gitlin described online training programs that are available for community-based health care providers and aides, although these options have not been rigorously tested in terms of what works best for each group in terms of improving care delivery and outcomes. She added that the information that should be transmitted about good dementia care is well known, but gaps remain in how to disseminate this information to individuals and to monitor outcomes.7

REFERENCES

Buckner, S., Darlington, N., Woodward, M., Buswell, M., Mathie, E., Arthur, A., Lafortune, L., Killett, A., Mayrhofer, A., Thurman, J., & Goodman, C. D. (2019). Dementia friendly communities in England: A scoping study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5123

Buckner, S., Lafortune, L., Darlington, N., Dickinson, A., Killett, A., Mathie, E., Mayrhofer, A., Woodward, M., & Goodman, C. (2022). A suite of evaluation resources for dementia friendly communities: Development and guidance for use. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 21(8), 2381–2401.

Buckner, S., Mattocks, C., Rimmer, M., & Lafortune, L. (2018). An evaluation tool for age-friendly and dementia friendly communities. Working with Older People, 22(1), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-11-2017-0032

Buckner, S., Pope, D., Mattocks, C., Lafortune, L., Dherani, M., & Bruce, N. (2019). Developing age-friendly cities: An evidence-based evaluation tool. Journal of Population Ageing, 12, 203–223. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12062-017-9206-2

Clemson, L., Laver, K., Rahja, M., Culph, J., Scanlan, J. N., Day, S., Comans, T., Jeon, Y.-H., Low, L.-F., Crotty, M., Kurrle, S., Cations, M., Piersol, C. V., & Gitlin, L. N. (2021). Implementing a reablement intervention, “Care of people with dementia in their environments (COPE)”: A hybrid implementation-effectiveness study. The Gerontologist, 61(6), 965–976.

Darlington, N., Arthur, A., Woodward, M., Buckner, S., Killet, A., Lafortune, L., Mathie, E., Mayrhofer, A., Thurman J., & Goodman, C. (2020). A survey of the experience of living with dementia in a dementia-friendly community. Dementia, 20(5). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1471301220965552

Federal Reserve Board. (2019). 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/scf_2019.htm

Forsyth, A., & Molinsky, J. (2021). What is aging in place? Confusions and contradictions. Housing Policy Debate, 31(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1793795

Fortinsky, R. H., Gitlin, L. N., Pizzi, L. T., Piersol, C. V., Grady, J., Robison, J. T., Molony, S., & Wakefield, D. (2020). Effectiveness of the care of persons with dementia in their environments intervention when embedded in a publicly funded home- and community-based service program. Innovation in Aging, 4(6).

Gitlin, L. N., & Czaja, S. J. (2016). Behavioral intervention research: Designing, evaluating, and implementing. Springer Publishing Company.

___________________

6 https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/network-age-friendly-communities/

7 See the end of Chapter 5 for a summary of this session and the following one.

Gitlin, L. N., & Hodgson, N. (2018). Better living with dementia: Implications for individuals, families, communities, and societies. Academic Press.

Gitlin, L. N., Reever, K., Dennis, M. P., Mathieu, E., & Hauck, W. (2006). Enhancing quality of life of families who use adult day services: Short- and long-term effects of the Adult Day Services Plus Program. The Gerontologist, 46, 630–639.

Gitlin, L. N., Roth, D. L., Marx, K., Parker, L. J., Koeuth, S., Dabelko-Schoeny, H., Anderson, K., & Gaugler, J. E. (2023). Embedding caregiver support within adult day services: Outcomes of a multi-site trial. The Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnad107

Gitlin, L. N., Winter, L., Dennis, M. P., Hodgson, N., & Hauck, W. W. (2010). A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: The COPE randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 304(9), 983–991.

Gitlin, L. N., Marx, K., Piersol, C. V., Hodgson, N. A., Huang, J., Roth, D. L. & Lykestsos, C. (2021). Effects of the Tailored Activity Program (TAP) on dementia-related symptoms, health events and caregiver wellbeing: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics (21)581. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02511-4

Jutkowitz, E., Pizzi, L. T., Shewmaker, P., Alarid-Escudero, F., Epstein-Lubow, G., Prioli, K. M., Gaugler, J. E., & Gitlin, L. N. (2023). Cost effectiveness of non-drug interventions that reduce nursing home admissions for people living with dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 19(9), 3867–3893.

Mathie, E., Arthur, A., Killet, A., Darlington, N., Buckner, S., Lafortune, L., Mayrhofer, A., Dickinson, E., Woodward, M., & Goodman, C. (2022). Dementia friendly communities: The involvement of people living with dementia. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 21(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012211073200

Molinsky, J., & Forsyth, A. (2018). Housing, the built environment, and the good life. The Hastings Report, 48(S3). https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.914

Molinsky, J., Berlinger, N., & Hu, B. (2022). Advancing housing and health equity for older adults: Pandemic innovations and policy ideas. Joint Center for Housing Studies. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_Hastings_Advancing_Housing_Health_Equity_for_Older_Adults_2022.pdf

Molinsky, J., Scheckler, S., & Hu, B. (2023). Centering the home in conversations about digital technology to support older adults aging in place. Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Pizzi, L. T., Jutkowitz, E., Prioli, K. M., Lu, E., Babcock, Z., McAbee-Sevick, H., Wakefield, D. B., Robison, J., Molony, S., Piersol, C. V., Gitlin, L. N., & Fortinsky, R. H. (2022). Cost–benefit analysis of the COPE program for persons living with dementia: Toward a payment model. Innovation in Aging, 6(1).

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(2), 65–76.

Reever, K. E., Mathieu, E., Dennis, M. P., & Gitlin, L. N. (2004). Adult Day Services Plus: Augmenting adult day centers with systematic care management for family caregivers. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 5(4), 332–339.

United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing. (n.d.). WHO’s work on the UN Decade of Health Ageing (2021–2030). https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Consumer Expenditures in 2018. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/consumer-expenditures/2018/pdf/home.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). 2021 American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/news/data-releases.2021.html

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2011). American Housing Survey for the United States: 2011. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2013/demo/h150-11.html

___. (2019). American Housing Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/ahs/data.2019.List_1739896299.html#list-tab-List_1739896299

Woodward, M., Arthur, A., Darlington, N., Buckner, S., Killett, A., Thurman, J., Buswell, M., Lafortune, L., Mathie, E., Mayrhofer, A., & Goodman, C. (2019). The place of dementia friendly communities in England and its relationship with epidemiological need. International Journal of Geriatrics, 34, 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4987

World Health Organization. (n.d.). The WHO Age-friendly Cities Framework. Age-Friendly World. https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/age-friendly-cities-framework