Aging in Place with Dementia: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 3 Community-Level Built Environments and Infrastructure

During the second session of the workshop, speakers had been asked to discuss how aspects of the built environment and community infrastructure affect aging in place for people with dementia by considering the following questions: What aspects of infrastructure affect the ability of people living with dementia to age in place? Can public spaces, transportation systems, and architecture be made more friendly for people living with dementia? Are there differences in urban and rural communities in the features that are most important to people living with dementia?

COGNABILITY: AN ECOLOGICAL THEORY OF NEIGHBORHOODS AND COGNITIVE AGING

Jessica Finlay (Assistant Professor of Geography, University of Colorado Boulder) explained that while studying aging in place experiences among racially and socioeconomically diverse older adults she learned that being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia was one of people’s greatest fears. Referencing the synthesis by Livingston et al. (2020) on how factors across the life course may theoretically prevent or delay dementia, she highlighted the specific role of built and social environments in affecting these risk factors.

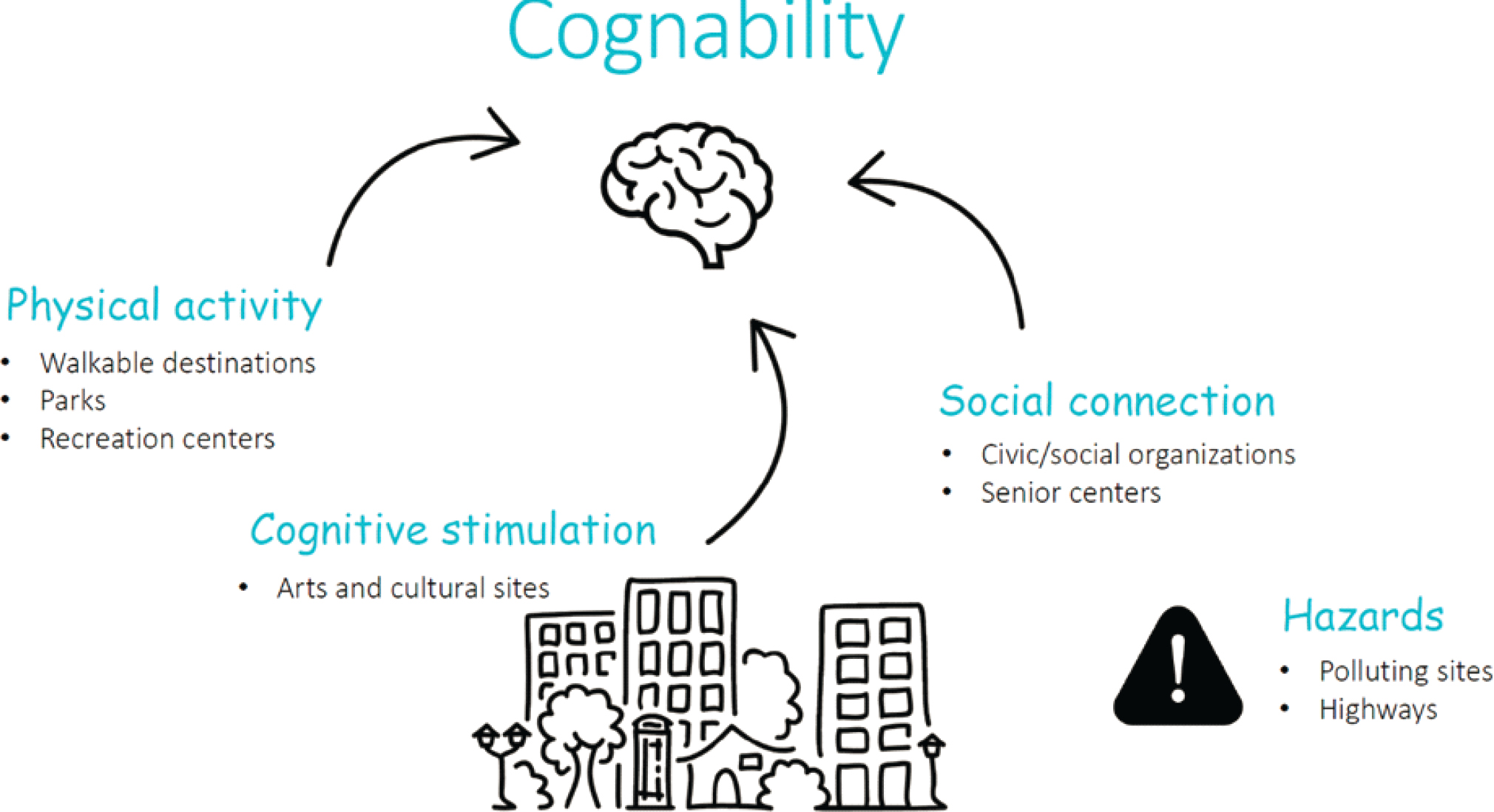

Finlay and a team at the University of Michigan created the cognability project to study this connection between neighborhoods and dementia risk. They coined the term “cognability,” which they initially defined as a theory of how supportive an area is to cognitive health through built and social environmental features that encourage physical activity, social connection, and cognitive stimulation in later life: for example, public libraries, educational programs, visual landmarks, coffee shops, shaded benches, well-designed crosswalks, traffic calming, mixed-use design, and public green spaces. To identify specific neighborhood features that may support healthy cognitive aging, Finlay and her team used a mixed-methods approach. Qualitative data collection and analysis helped understand where and how older adults socialize, exercise, and engage in cognitively stimulating activities outside of their homes; quantitative data collection and analysis helped determine how the availability of and access to these neighborhood sites are associated with cognitive function.

Finlay first provided an overview of the qualitative data collection. As part of the Aging in the Right Place (AIRP) study, 125 interviews were conducted with older adults from 2015 to 2016 in 3 demographically and geographically varied areas of Minneapolis to learn about their neighborhood experiences and their perceptions of necessary supports for aging in place. The average age of the interview participants was 71.3 years; 67% identified as female and 33% as male; 57% identified as White, 25% identified as Black, and 18% self-identified as other races and ethnicities; 34% identified as married and 66% as not married; 33% were living alone;

and 57% had a high school education and 43% had some postsecondary education (Finlay & Bowman, 2017). To capture a broader set of experiences and places, Finlay also conducted an ethnography with a subset of 6 participants over 12 months.

Finlay next presented an overview of the quantitative data collection, which leveraged the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Ongoing since 2003, the REGARDS study includes more than 30,000 non-Hispanic Black and White adults. Annual follow-up with participants includes cognitive testing, residential address tracking, and physical and mental health measurement. She explained that multiple sources of information from the REGARDS study—for example, tests for language and executive function, learning and memory, and recall and orientation—were used to develop a global measure of cognition. The quantitative sample included 21,151 participants, limited to those in urban and suburban areas to align with the sample in the AIRP study. The average age of the REGARDS sample at assessment was 67 years; 56% identified as female and 44% as male; 60% identified as White and 40% as Black; and 60% had a high school education and 40% had some postsecondary education. Interestingly, cognition varied widely depending on where the person lived.

Finlay emphasized that the AIRP study was used for a qualitative thematic analysis to understand how and why participants perceived and used their local environments. The REGARDS study was used for a quantitative analysis using multilevel linear regression models and generalized additive models to measure global cognitive function and neighborhood features (with consideration for kernel density, individual buffers, and census tracts) among participants active 2006–2017, adjusted for individual- and area-level covariates.

Findlay explained that these qualitative and quantitative analyses were used to create pathways to build the concept of cognability. The qualitative analysis revealed that places for social connection and support among older adults included senior centers, civic and social organizations, and food and drinking establishments that were physically and economically accessible and often walkable destinations (Finlay, Esposito, Li, Kobayashi, et al., 2021). The quantitative analysis revealed that civic and social organizations and senior centers were positively associated with cognitive function. Although she noted that this exploratory work primarily uncovered correlations, it also helped to determine that social connection is one of the pathways to cognability.

To establish another pathway to cognability in relation to physical activity, Finlay and her team found, through the qualitative analysis, that places for active aging included walkable destinations, local parks, and recreation centers (Finlay, Esposito, Li, Colabianchi, et al., 2021). The quantitative analysis suggested that walkable destinations, parks, and recreation

centers were all positively associated with cognitive function. She noted that the influences of cognitive stimulation through arts and cultural sites, as well as the hazards from highways and pollution sites, were also explored to better understand the full concept of cognability (Finlay, Yu, et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2023): see Figure 3-1.

Finlay indicated that all of these findings about the connections between neighborhood and cognitive health can be combined to create a whole-neighborhood model (Finlay et al., 2022). First, the quantitative analysis revealed that civic and social organizations had a strong positive association with better health outcomes. Positive associations were also identified for the arts, museums, and recreation centers. Highways had a strong negative association with cognitive health, and coffee shops and fast food establishments had a negative association with cognitive function. Second, Finlay and her team considered whether neighborhood features were more or less important to different subpopulations given that structural racism, sexism, and classism could make sites less accessible and thus less beneficial for some people. She explained that, although allowing the full set of neighborhood drivers of cognitive function to vary by race, gender, and education did not yield substantial improvements to the full model, some individual neighborhood features differed significantly by group. For example, religious organization density was significantly and positively associated with cognitive health among Black adults (Taylor et al., 2017). As this work continues in the future, Finlay described an opportunity for theoretically motivated and targeted investigations.

In closing, Finlay emphasized that much work remains to refine the concept of cognability. She and her team developed a website that maps cognability scores by location,1 which may help determine where to target limited resources to bolster neighborhoods more equitably. Next steps include validating and extending the concept of cognability with nationally representative samples, as well as advancing understanding of earlier life environments and exposures, gene–environment interactions, rural communities, international contexts, and perceived social environments and expectations. Because COVID-19 significantly changed neighborhood landscapes and aging in place, she noted that mixed methods analyses are under way to develop “cognability 2.0.”

DRIVING AND AGING IN PLACE: EMOTIONS, MOBILITY, AND TECHNOLOGY

Emmy Betz (Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine) highlighted the need to develop strategies to address difficult topics in a more supportive way as people age. She described a

___________________

SOURCE: Adapted from Finlay, Yu, et al. (2021); Yu et al. (2023).

study on how people make decisions about the appropriate time to stop driving, noting that people’s needs change over time, and most people outlive their ability to drive safely by approximately 10 years (Foley et al., 2002). Many older adults without cognitive impairment can recognize sight and other deficits and may restrict themselves from driving at night, driving long distances, or driving in bad weather; some may simply choose not to drive as their lifestyles change. However, other older adults, especially those in rural communities or those without reliable public transit, have a practical need for transportation and thus continue to drive. Furthermore, for some older adults, the act of driving symbolizes an important sense of freedom. Therefore, she cautioned against making assumptions about people’s needs as they age.

Betz noted that while these aspects of physical and mental health may make continuing to drive important, associated risks also exist. For example, driving is a way to maintain social engagement and avoid isolation, but physical conditions can affect driving ability. She emphasized that balancing the physical and mental health needs of older adults with the physical and mental health needs and financial and logistical issues of family members (who may be called on to transport them or, conversely, need their assistance in transporting grandchildren) is critical. This interrelationship between older adults and their families is complicated, and not all older adults have a family structure surrounding them.

Betz indicated that communities play a key role in preserving safety, reducing stigma, distributing resources equitably, and maintaining engagement for older adults. Elaborating on the issue of stigma against older drivers and road safety, she noted that driver injury and death rates increase with age; however, because older adults are more likely to drive slower, less likely to drive at night, and less likely to drive impaired than younger drivers, the predominant risk to pedestrians is from younger drivers. She explained that location is also key to understanding the risks and resources for older adults who drive, as well as to making decisions about when to stop driving (Payyanadan et al., 2018). For example, those who live in cities can have their groceries delivered, which means that driving is not needed for essential tasks. Those who live in rural areas may need to keep driving to meet their daily needs; however, because rural areas are less densely populated, residents have less chance of hurting someone while driving.

Betz reiterated that meeting the physical and emotional needs of older people (e.g., going to religious services, to the doctor, to the grocery store) and avoiding physical and emotional harms (either from vehicle accidents or from negative health outcomes that may result in stopping a person’s freedom to drive) is a challenge. Cognitive impairment in particular is a serious risk for driving, so she encouraged normalizing conversations about “driving health” by engaging people in planning for and decision making

about the future before significant impairment develops and harm results (Betz et al., 2013, 2016). She noted that caregiver perspectives are particularly important in this space.

Betz proposed that some of these difficult issues could be addressed by designing interventions that are person centered and that leverage technology to meet the varied needs of older adults. She presented a transtheoretical model in relation to driving, in which adults move from thinking about the issue when mobility remains unchanged, to recognizing when mobility begins to change, to preparing with reduced driving, to stopping driving and maintaining mobility in other ways (Meuser et al., 2013). Factors that affect this journey include cognitive ability, attitudes, and social circumstances. She noted that work is under way to understand how a decision aid could help with this decision-making process. For instance, she and her team conducted a randomized controlled trial that leveraged this transtheoretical model with older adults who are currently driving but have a medical condition that may compel them to stop driving in the next few years. Results of the trial indicated that the decision aid reduced ambivalence, decreased decisional conflict, and increased knowledge about decisions to stop driving (Betz, Hill, et al., 2022).

Betz explained that this randomized controlled trial also revealed that older adults’ experiences during COVID-19 provided important insights about the potential for and benefits of virtual engagement. For example, Betz, Fowler, et al. (2022) noted that 70% of older people reduced their driving during COVID-19 for a variety of reasons compared with only 26% before COVID-19. Furthermore, despite the increased social isolation of COVID-19, increased depression and stress were not observed among the older adults in this study.2 Some learned how to use Zoom for social connection and realized that they could survive by driving less, while others drove just to escape the confines of their homes, thus reinforcing the complexity of people’s psychological relationship with driving and the challenges of decision making about driving.

Moving forward, Betz advocated for the use of technology to enable increased alternative transportation options (e.g., Uber Central or Lyft’s Lively Senior Ride Service, which caretakers can use to schedule rides for older people who may have difficulty navigating the platforms), as well as for efforts to make these alternatives financially feasible. She noted, however, that additional alternatives to transportation are needed—for example, online religious services, grocery delivery, and telehealth appointments. In closing, Betz mentioned that work is ongoing to create plans for safe mobility among older adults; she encouraged workshop participants to read Transportation and Aging: An Updated Research Agenda to Advance Safe

___________________

2 Betz indicated that the cohort was comprised of educated and socioeconomically wealthy adults.

Mobility among Older Adults Transitioning from Driving to Non-driving (Dickerson et al., 2019).

AGING IN PLACE WITH DEMENTIA-FRIENDLY HOUSING

Terri Lewinson (Associate Professor, Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice) began her presentation by sharing words from Dolores Hayden: “Whoever speaks of housing must also speak of home; the word means both the physical space and the nurturing that takes place there” (Hayden, 1984, p. 63). Lewinson noted that when discussing housing plans and policies, people often lose focus of these social and communal experiences that occur in the physical space of the home. The dynamic psychosocial constructs that influence whether one calls a “house” a “home” include shelter and protection, autonomy and privacy, warmth, personalization and self-identity, aesthetics, continuity (i.e., patterned behaviors), and centrality (i.e., where you return at the end of every day and are welcomed). She asserted that many of these constructs may be disrupted or difficult to achieve in an institutional setting, in public housing, or when transitioning to a new place.

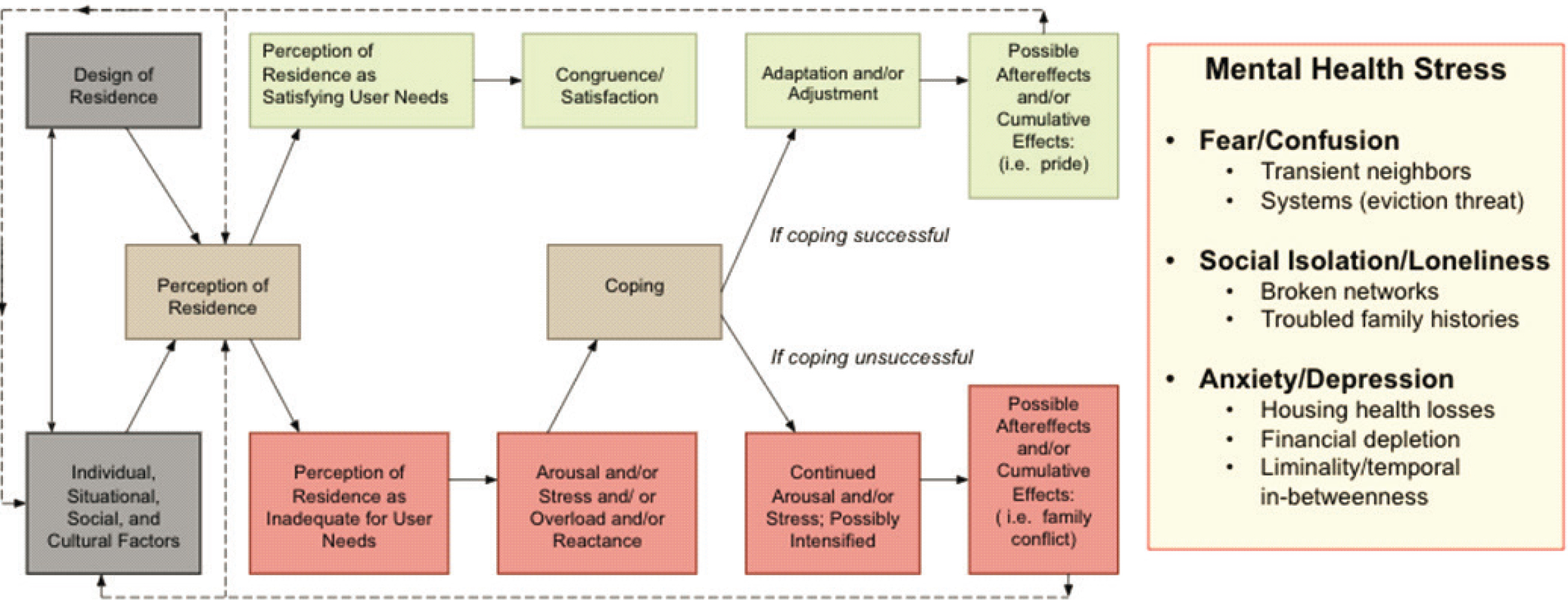

Lewinson explained that one’s “perception of residence” helps understand whether a person’s environment is healthy or unhealthy. The residential stress model, an environment–behavior model for residential settings (see Bell et al., 2001), can be leveraged to help understand these perceptions, which are influenced by the design of the residence; by the person’s role(s) in community, family, and social groups; and by the ability of the residence to meet the person’s needs: see Figure 3-2.

For those who are “precariously housed,” often in extended-stay hotels and on the verge of homelessness, Lewinson noted that this model illuminates numerous mental health stressors—such as fear and confusion about the potential harm from transient neighbors and of systems that could initiate eviction; social isolation and loneliness owing to broken networks and troubled family histories related to abuse or nonacceptance of identity; and anxiety and depression over environment-related health losses, financial depletion, and temporal housing “in-betweenness.” She emphasized that these mental health stressors combine with social and physical stressors to compound housing stressors; however, this model also highlights possible coping strategies that people can leverage to improve their housing experiences and thus their overall well-being.

Lewinson remarked that the housing and health disparities conceptual model (Swope & Hernandez, 2019), which identifies structural oppressions that keep people in precarious housing, is another valuable tool to help understand the relationship between housing and health. For example, it identifies how people lose financial and health equity throughout their

SOURCE: Adapted from Bell et al. (2001, pp. 402–403).

lives. Because 39% of extremely low–income renters are older people, she indicated that aging in place for people who are precariously housed is incredibly difficult because of a lack of resources. She highlighted current research funded by the National Institute on Aging that explores how people experience their homes and some of the stressors they confront and address. In particular, this research considers the role of resident service coordinators in supporting aging in place with the inclusion of dementia-friendly programming.

With consideration of these challenges related to the relationship between housing and health that impacts one’s ability to age in place, Lewinson presented the key necessities for aging in place and dementia-friendly planning: (a) safe, accessible, and affordable housing; (b) community support services that are integrated and accessible; (c) accessible health care and crisis intervention; (d) transportation; (e) safety measures; (f) social and recreational opportunities; (g) caregiver support; (h) legal and financial support; (i) technology and communication; (j) collective advocacy and policy support; as well as (k) dementia-friendly spaces and resources, including sensory-friendly environments and recreational facilities, parks, and activities.

DISCUSSION

Sharing questions from workshop participants, Wendy Rogers (Khan Professor of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign; planning committee member), moderated a discussion among the session’s three speakers. She highlighted several themes that emerged across their presentations: the value of person-centric approaches, problematic issues of ageism and related stigma, variance in individual issues across older people, and the potentially helpful role of technology.

Rogers asked the speakers to identify key issues in urban versus rural settings related to the study of older people with dementia. Finlay replied that neighborhood measurement should change to accommodate rural and urban contexts. Although the types of community organizations in rural and urban areas may be very different, she noted that commonalities also exist that support aging in place in any setting. Betz added that the differences between urban and rural settings are also influenced by the type of place in which older adults live—for example, in a multigenerational home with caregivers or in a home alone. Furthermore, she stressed that the exploration of older adults’ experiences is important; rural areas have many strengths owing to their tight-knit communities, but both urban and rural areas have several unique positive and negative features related to aging in place with dementia. Lewinson commented that resources may be restricted or unavailable in rural areas. She also explained that in both rural and

urban areas, providing coordinated services is essential, and existing local relationships and frameworks are important for building engagement and support for people living with dementia. For example, she said that simple signage helps older people navigate their communities, and diverse housing design helps enable aging in place—but the United States is lagging in its housing offerings for people living with dementia and their caregivers.

Workshop planning committee member Sarah Szanton (Dean and Patricia M. Davidson Health Equity and Social Justice Endowed Professor, Johns Hopkins University) mentioned that Carehaus,3 located in Baltimore and Houston, creates buildings of housing units both for people with and without dementia and for their direct care workers and their families. Over time, these direct care workers receive equity in the building in addition to their wages. She described this as a promising model of creating new “third spaces” for older people with dementia. Lewinson cited another model, Hotel Louisville4 in Kentucky, which integrates social service agencies in the same buildings where precariously housed people live.

Szanton remarked that structural racism across the life course influences how activity spaces are used, as many people may feel like these spaces were not built for them. Finlay observed that using geography as a measure of access is inadequate—for example, a local park with a confederate statue is not accessible to all neighborhood residents, despite its proximity. Issues related to ableism also arise for spaces that are difficult for people to navigate. She advocated for the increased use of mixed methods research to begin to expand access, equity, and justice, especially for underserved communities.

Rogers posed a question to Finlay about variance within neighborhoods and another question about whether scent sensitivity has been explored as an explanation of why people do not frequent certain places. Finlay replied first that understanding variance within neighborhoods is difficult with quantitative research; qualitative research is more valuable. For example, while conducting interviews, she found that people who lived next door to each other reported completely different experiences of the same environment. Second, she said, that although limited research exists related to the sense of smell, there is much more research on auditory experiences and innovations in soundscapes because many locations are too loud for older people.

Rogers then asked Lewinson whether research has been conducted on the role of pets in aging in place for people with dementia. Lewinson replied that studies of residents in assisted living places found that pets help calm residents and improve their socialization with other residents. She described this as an interesting area for future research.

___________________

Rogers inquired about other certifications, training, or frameworks to guide people in age-inclusive design. Lewinson highlighted the notion of green design and encouraged the creation of more aesthetic spaces where older people can engage with nature and their senses. Betz expressed her hope that vehicle designers would begin to consider the needs of older adults and those with visual or physical challenges as they design new vehicle technology (e.g., simplified touchscreens and navigation tools).

Finlay pointed to work in the field of environmental gerontology, such as implementing different colored doors and noise-reduction strategies, to help older people navigate complex settings. She suggested building on successful training in occupational therapy to help people with cognitive impairment develop strategies to navigate new environments. She also noted that there are effective models for facilitating connections and care for older adults who might not yet be identified as vulnerable. For example, postal workers in the United Kingdom were trained to chat with isolated older adults on their route as a way to check-in, build community, and provide support if needed. Szanton encouraged an increased focus both in research and in practice on engaging older adults with dementia who live by themselves—which is approximately one-third of people with dementia. Some of these adults do not have caregivers or a support network, and they are often excluded from research because they are more socially isolated and thus more difficult to enroll in studies.

Rogers asked Betz about issues of technology acceptance among older adults with dementia and strategies to ensure the availability of instructional support. Betz responded that research is under way to explore the uptake and value of various vehicle technology features: For example, some evidence supports the benefits of passive interventions, such as automatic braking capabilities (Eby et al., 2018). However, the effectiveness of other features, such as flashing lights in sideview mirrors to warn of blind spots, remains in question. She added that financial equity is a critical dimension of any discussion about technology interventions, because not everyone can afford to buy a new car with these or other features. She noted that there is a study among older drivers that showed significant variance in technology readiness, and she underscored that instructional support is essential for the success of any technology intervention, as is developing strategies to embed support resources instead of making people find the resources themselves.

SUMMARY OF WORKSHOP DAY 1

Planning committee chair Emily Agree (Research Professor and Associate Director, Hopkins Population Center, Johns Hopkins University) summarized her key takeaways from the first two sessions of the workshop. Speakers discussed frameworks and conceptual models for thinking about aging in place for people with dementia. Several speakers indicated that the

concept of place varies (e.g., geographically, virtually, by community type) and should be considered broadly, not only as a diverse context in which people live, but also as an interactive space that evolves in tandem with the way people live their lives. Furthermore, the preference to age in place is not universal. For instance, some older adults are “stuck” in place as they age and unable to improve their environments because of lifelong exposure to structural discrimination and disadvantages.

Agree noted that several speakers had discussed the way researchers approach this work. For example, the community plays a critical role in supporting people with dementia, and these ideas about community can be translated into programs in diverse communities. Working with existing community groups and leaders is essential to implement interventions in the real world. Additionally, several speakers had discussed the role that the built and community-level environment plays for aging in place for people with dementia—including such “third spaces” as senior centers, parks, and recreation centers outside the home—in maintaining cognitive health and improving well-being. However, different communities experience different benefits from different institutions. She noted that several speakers asserted that exploring the physical barriers that might hinder access to those spaces is essential.

Agree highlighted that one speaker had discussed the central role that driving plays in U.S. culture and identity. Decision aids could be helpful to reduce stress and conflict within families over this issue and to make decisions about stopping driving more acceptable to older people as they move into their next stage of life. Alternatives to driving would also be beneficial, as would forming alliances with new stakeholders to promote livable and age- and dementia-friendly communities with transportation options. Finally, some speakers had described the meaning of home and how housing instability and residential insecurity exacerbate problems for people aging with dementia. Strategies to provide safe and affordable housing as well as community support services are needed, especially for those who are the most vulnerable because of their earlier life experiences and current situations.

REFERENCES

Bell, P. A., Greene, T. C., Fisher, J. D., & Baum, A. (2001). Environmental psychology (5th ed.). Harcourt Publishers.

Betz, M. E., Fowler, N. R., Duke Han, S., Hill, L. L., Johnson, R. L., Meador, L., Omeragic, F., Peterson, R. A., & DiGuiseppi, C. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adult driving in the United States. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(8), 1821–1830.

Betz, M. E., Hill, L. L., Fowler, N. R., DiGuiseppi, C., Duke Han, S., Johnson, R. L., Meador, L., Omeragic, F., Peterson, R. A., & Matlock, D. D. (2022). “Is it time to stop driving?”: A randomized clinical trial of an online decision aid for older drivers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(7), 1987–1996.

Betz, M. E., Jones, J., Petroff, E., & Schwartz, R. (2013). “I wish we could normalize driving health”: A qualitative study of clinician discussions with older drivers. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(12), 1573–1580.

Betz, M. E., Scott, K., Jones, J., & DiGuiseppi, C. (2016). “Are you still driving?”: Metasynthesis of patient preferences for communication with health care providers. Traffic Injury Prevention, 17(4), 367–373.

Dickerson, A. E., Molnar, L. J., Bédard, M., Eby, D. W., Berg-Weger, M., Choi, M., Grigg, J., Horowitz, A., Meuser, T., Myers, A., O’Connor, M., & Silverstein, N. M. (2019). Transportation and aging: An updated research agenda to advance safe mobility among older adults transitioning from driving to non-driving. Gerontologist, 59(2), 215–221.

Eby, D. W., Molnar, L. J., Zakrajsek, J. S., Ryan, L. H., Zanier, N., Louis, R. M. S., Stanciu, S. C., LeBlanc, D., Kostyniuk, L. P., Smith, J., Yung, R., Nyquist, L., DiGuiseppi, C., Li, G., Mielenz, T. J., Strogatz, D., & LongROAD Research Team. (2018). Prevalence, attitudes, and knowledge of in-vehicle technologies and vehicle adaptations among older drivers. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 113, 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2018.01.022

Finlay, J. M., & Bowman, J. A. (2017). Geographies on the move: A practical and theoretical approach to the mobile interview. The Professional Geographer, 69(2), 263–274.

Finlay, J., Esposito, M., Langa, K. M., Judd, S., & Clarke, P. (2022). Cognability: An ecological theory of neighborhoods and cognitive aging. Social Science & Medicine, 309, 115220.

Finlay, J., Esposito, M., Li, M., Colabianchi, N., Zhou, H., Judd, S., & Clarke, P. (2021). Neighborhood active aging infrastructure and cognitive health: A mixed-methods study of aging Americans. Preventive Medicine, 150, 106669.

Finlay, J., Esposito, M., Li, M., Kobayashi, L. C., Khan, A. M., Gomez-Lopez, I., Melendez, R., Colabianchi, N., Judd, S., & Clarke, P. J. (2021). Can neighborhood social infrastructure modify cognitive function? A mixed-methods study of urban-dwelling aging Americans. Journal of Aging and Health, 33(9), 772–785.

Finlay, J., Yu, W., Clarke, P., Li, M., Judd, S., & Esposito, M. (2021). Neighborhood cognitive amenities? A mixed-methods study of intellectually-stimulating infrastructure and cognitive function among older Americans. Wellbeing, Space & Society, 2, 100040.

Foley, D. J., Heimovitz, H. K., Guralnik, J. M., & Brock, D. B. (2002). Driving life expectancy of persons aged 70 years and older in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 92(8), 1284–1289.

Hayden, D. (1984). Redesigning the American dream: The future of housing, work, and family life. W. W. Norton & Co.

Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne, C., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Costafreda, S. G., Dias, A., Fox, N., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Kivimäki, M., Larson, E. B., Ogunniyi, A., . . . Mukadam, N. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet, 396(10248), 413446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

Meuser, T. M., Berg-Weger, M., Chibnall, J. T., Harmon, A. C., & Stowe, J. N. (2013). Assessment of Readiness for Mobility Transition (ARMT): A tool for mobility transition counseling with older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 32(4), 484–507.

Payyanadan, R. P., Lee, J. D., & Grepo, L. C. (2018). Challenges for older drivers in urban, suburban, and rural settings. Geriatrics (Basel), 3(2), 14.

Swope, C. B., & Hernandez, D. (2019). Housing as a determinant of health equity: A conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine, 243, 112571.

Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., Lincoln, K., & Woodward, A. T. (2017). Church-based exchanges of informal social support among African Americans. Race and Social Problems, 9(1), 53–62.

Yu, W., Esposito, M., Li, M., Clarke, P., Judd, S., & Finlay, J. (2023). Neighborhood “disamenities”: Local barriers and cognitive function among Black and White aging adults. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 197.