Aging in Place with Dementia: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 2 Frameworks for Aging in Place

2

Frameworks for Aging in Place

For the first session of the workshop, speakers examined how existing frameworks for aging in place could be adapted to incorporate people living with dementia. Speakers and workshop participants had been asked to explore the following questions: How well do models of the neighborhood and community factors that facilitate aging in place fit people who are living with dementia? What additional factors need to be taken into account? Are there unique challenges that differ from those of people with physical

disabilities or chronic diseases? How do structural sources of disadvantage affect people living with dementia in their communities?

THEORIES OF PLACE AND AGING: AN ENVIRONMENTAL GERONTOLOGY PERSPECTIVE

Frank Oswald (Professor of Interdisciplinary Aging Research, Goethe University, Frankfurt) discussed how, over the past few decades, home- and community-based environments have gained increased attention in the field of environmental gerontology. The process of theorizing place and aging includes (a) reconsidering “aging in place” and the “place of place” in the everyday lives of older adults, (b) identifying “enduring” and “novel” issues that have shaped theory on place and aging, and (c) exploring both traditional and more recent theoretical perspectives from environmental gerontology that provide context for further research on aging in place for people with dementia.

First, Oswald explained, the concept of “aging in place” indicates a person’s desire and opportunity to remain in the home and live independently, with some assistance, for as long as possible without having to move to another place (Pani-Harreman et al., 2021). However, he noted, instead of using the phrase “aging in place,” some scholars believe that “place” should be an overarching concept to address “aging” in the context of its many challenges, opportunities, and risks (for example, see Cutchin, 2018; Rhodus & Rowles, 2023; Rowles, 1993). This concept of “place” helps to understand how older adults are embedded in contexts, how they shape contexts, and how contexts influence the course of aging (for example, see Lewis & Buffel, 2020). Therefore, in addition to its importance at the micro-level, place relates to the meso- and macro-levels of neighborhood and community (for example, see Greenfield et al., 2019). As a result, he continued, place and aging interact and depend on historical development and cohort flow, and they are constantly changing in response to historical–cultural influences and transitions and global trends, such as digitalization or climate change.

Second, Oswald outlined the “enduring” perspectives of place: it may enhance or hinder access, orientation, and resource use at home, in the neighborhood, and in the community; it may support or constrain the experiences of privacy, comfort, recreation, social exchange, and community embeddedness; it may serve as a source of identity and meaning-making on different contextual layers; and it may provide the socio-physical frame for processes of continuous change over various time metrics. In addition, “novel” perspectives of place are shaped by ongoing megatrends (e.g., technology that enables or constrains place-making), increased diversity among older adults (e.g., ethnicity, cognitive status, lifestyle), and

environmental and social innovations in community-based housing and support networks.

Third, Oswald noted, three generations of theories have conceptualized place and aging (Oswald et al., 2024). From the 1960s to the 1990s, many scholars viewed a person and the environment as independent entities. During this first generation of theory, research primarily focused on the physical dimension of the environment. From 2000 to 2015, the person and the environment were viewed instead as interwoven entities that influenced one another. New emphases on “agency” (i.e., becoming an agent in one’s own life through intentional behaviors imposed on the socio-physical environment; for example, see Bandura, 2001, 2006) and “belonging” (i.e., non-goal-oriented cognitive and emotional process that makes a space a place; for example, see: Rowles, 1983; Rubinstein, 1987) emerged, and digitalization became a critical issue during this era of research. He remarked that current theoretical approaches have expanded this understanding of place to include more diverse contexts. Approaches in this third generation of theory include transactional and co-constructed perspectives on the interrelationship between person and place. New approaches are inspired by fields beyond environmental gerontology (e.g., human geography and material gerontology) that could influence future theory development as well as the application of interventions (e.g., Höppner & Urban, 2018; Rhodus & Rowles, 2023).

Oswald offered the following key takeaways from this review of theories of place and aging. New developments in the concept of place support the notion that people and environments are co-constitutive. Therefore, second- and third-generation theories are more appropriate than first-generation theories to address enduring and novel issues of place and aging in research and application. He added that differentiated measures have led to differentiated findings on the level of transaction (e.g., processes of agency and belonging) and on the level of participatory approaches (e.g., age-friendly communities). He advocated for a new focus on how people and places develop together or apart in a certain environment, instead of on what an age-friendly environment is and how place attachment1 can be facilitated in later life.

Oswald next turned to a discussion of existing empirical evidence on person–environment exchange processes for people in the early stages of dementia. He described a scoping review based on a model of context dynamics in aging as a framework for aging in place for people with dementia (Niedoba & Oswald, 2023). This model categorized the study design and different environmental dimensions of individuals’ life spaces, as well as the person–environment exchange processes of agency and belonging. He explained that 55% of the studies in the review used qualitative methods (e.g.,

___________________

1 The term is explored in detail in Diener & Hagen (2022).

ethnography, photovoice); quantitative methods were used primarily to measure processes of agency (e.g., global positioning system assessments). Most of the studies prioritized the social and the physical environments, and only a few addressed care, technology, or socioeconomic factors.

Describing the review’s evidence on the process of agency, Oswald indicated that people living with dementia can deliberately reduce, maintain, use, or expand their life spaces. Although people in the early stages of dementia often experience a “shrinking world” (Duggan et al., 2008), with reduced global movement (Tung et al., 2014) and increased mobility restriction (Wettstein et al., 2015), the extent to which places are visited depends on their type and meaning. For example, consumer, administrative, and self-care places, as well as social, cultural, and spiritual places and places for recreational and physical activities, are visited less often than they used to be; places with contact with nature, for medical care, for staying in touch with their social network, and the neighborhood continue to be visited (Margot-Cattin, 2021). Therefore, according to Ward et al. (2021), even after being socially excluded, people living with dementia can rebuild their social networks, strengthen existing relationships, and find spaces where they can establish new social contacts.

Describing the review’s evidence on the process of belonging, Oswald commented that people living with dementia still perceive connectedness and familiarity with the socio-physical environment, although a feeling of belonging may decrease. Studies indicate a persistent desire for belonging (for example, see Han et al., 2016; Mattos, 2016) and the promotion of community belonging through participation in social groups (for example, see Söderhamn et al., 2014), as well as perceived familiarity and safety at home (for example, see Duggan et al., 2008; van Gennip et al., 2016), to reinforce continuity of one’s sense of self and identity (Margot-Cattin, 2021). Besides the home (Li et al., 2019), objects (Dooley et al., 2021) and, interestingly, clothing can also support identity (Buse & Twigg, 2016), especially in the early stages of dementia. As dementia progresses, visits to relatively new current places may become unfamiliar and less important than visits to known past places (Duggan et al., 2008; Genoe, 2009; Pace, 2020). According to van Wijngaarden et al. (2019, p. 14): “Gradually, the world becomes an increasingly alien place. The feeling of basic familiarity diminishes. Meaningful connections between the self and the outside space are interrupted, creating feelings of not-being-at-home and insecurity.”

Oswald shared the following key takeaways from this review of evidence on person–environment exchange processes. He noted that “place” plays a significant role in either enabling or impeding the transition into dementia. Although people making this transition may experience a loss of agency and sense of belonging, stigmatization, and social exclusion, they are not victims of their environments because they can co-create life spaces proactively. He underscored that environmental stability; familiar

surroundings; and possibilities to engage with people, places, and objects might foster continuity of one’s feeling of self despite this progression of dementia. Because current findings are limited to a traditional framework on distinct physical and social environments and conventional concepts of person–environment exchange processes (for example, see Oswald & Wahl, 2019), he suggested directing more attention toward new theories as well as studying both places outside one’s home (for example, see Sugiyama et al., 2022) and the technological environment (for example, see Gaugler, 2023).

STRUCTURAL DETERMINANTS OF AGING IN A PLACE: A STORY

“AJ” Adkins-Jackson (Assistant Professor of Epidemiology and Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University) provided an overview of the relationship between social and structural determinants and aging in place, inspired by the lived experience of her grandmother, Helen Musick. Following Gómez et al. (2021), Adkins-Jackson defined social determinants as the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, seek health care, and age.

Reflecting first on the social determinant of education, Adkins-Jackson noted that Helen, born in 1930, attended an integrated elementary school in Syracuse, New York, and pointed out that much of the discussion surrounding the social determinant of education focuses on the relationship between education and future cognitive ability. She cited a report that suggested that addressing disparities in access to education early in life might reduce the risk factor for dementia prevalence by 7% (Livingston et al., 2020). However, she said, the issue is far more complex: education does not necessarily provide cognitive exposure, especially for today’s older adults of color who experienced pain and trauma as schools became desegregated. Although the evidence is mixed on the benefits of integrated education in particular, she underscored that education provides access to future occupations and income that then influence one’s ability to have a good quality of life and the potential to age in place.

Although Helen attended an integrated school, she lived in a segregated neighborhood, the borders of which were policed. Thus, Adkins-Jackson explained, where a person lives is another critical social determinant. She asserted that communities deprived of resources were (and are) located across from thriving communities by design, not by happenstance. For example, she shared a 1937 map of Syracuse that displayed highways built directly through Black neighborhoods, causing extensive disruption and displacement.

Moving to Los Angeles in 1949, Helen encountered similar community segregation. She married and found work cleaning homes and caring for children of White families located 10 miles from her own neighborhood.

Adkins-Jackson indicated that where a person works is another key social determinant. For instance, the workplace might expose employees to toxins that could affect physical and cognitive abilities later in life. However, she explained, most of the dementia research focuses on the relationship between work and cognitive stimulation. Labor-intensive jobs are thought to be less cognitively stimulating than “desk jobs,” yet, in reality, using both the body and the mind for work is incredibly cognitively stimulating. She described this as an example of how people and their work are devalued across generations and added that society often underestimates the role that work plays in people’s potential to age in place. For instance, often only full-time employment provides the health insurance and financial stability required to enable a good quality of life. According to the National Partnership for Women and Families (2023), Black women are at a particular disadvantage, making only 64 cents to the dollar in comparison with White men, and their quality of life is directly and negatively affected by this wage theft.

In addition to the distance Helen had to travel for work, she had to ride a bus to take her children to the park because her neighborhood did not have one. Adkins-Jackson highlighted that this social determinant—where a person plays—is influenced significantly by the notions of both “choice” and “access.” She explained that structural policies, such as eminent domain, allow governments to take property from residents and convert it for public use. For instance, Central Park, where people now play, was constructed after the predominantly Black Seneca Village residents were forced to leave in 1857 and their homes were subsequently torn down.

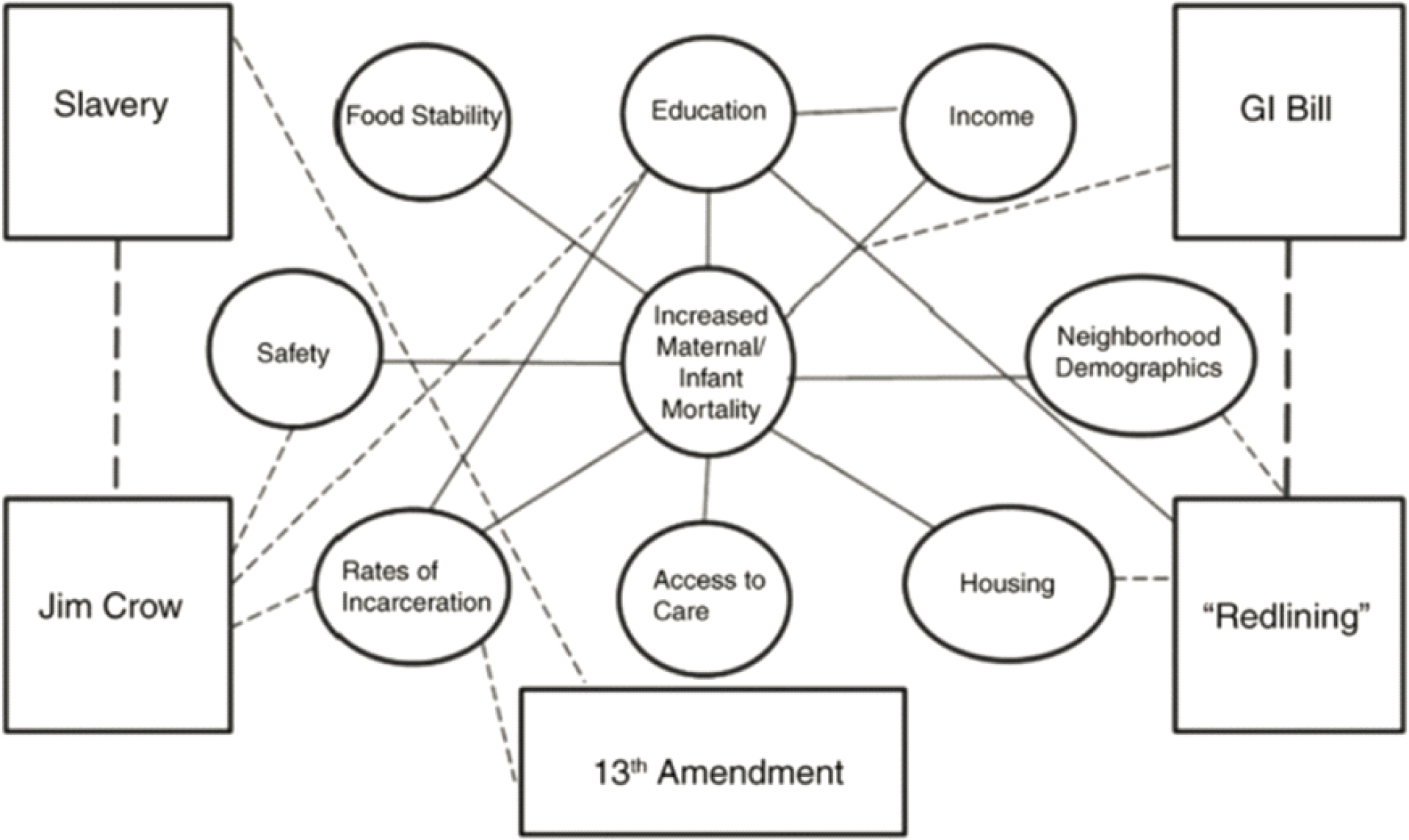

With consideration for this historical context, Adkins-Jackson transitioned from the discussion of social determinants to a discussion about structural determinants—which she defined as the pervasiveness and deliberateness with which policies, societal norms and structures, and governing processes result in inequities in the distribution of power, resources, opportunities, and social determinants of health (Gómez et al., 2021; Crear-Perry et al., 2021): also see Figure 2-1.

Adkins-Jackson commented on several structural determinants that merit additional research, including homophobia, ageism, ableism, capitalism and other socioeconomic biases, religious biases, xenophobia and other geographic biases, structural sexism and genderism, and structural racism and other ethnocultural biases—all of which determine a person’s quality and quantity of life (Adkins-Jackson et al., 2023). In particular, structural racism operates by grouping individuals on the basis of categories of perceived similarities; groups are then assigned value through a ranking system; and racism structures opportunity and dictates how people within the system treat others. With particular attention toward the structural violence that many Black communities have endured, she asserted that structural racism determines who has the opportunity to age—and to age

NOTE: Boxes connected by dashed line = structural determinants; circles and solid lines = distribution of social determinants

SOURCE: Roach (2016). Reprinted with permission.

in place. Health thus becomes a commodity in a discriminatory system, she continued; people try to survive, but the system causes them to die in place (Gee et al., 2019). Furthermore, this exposure to racism occurs across the life course reflected in, among other things, certain anticrime bills, intergenerational poverty, racist encounters with medical professionals, and accumulating pollution in communities (Glymour & Manly, 2008).

Resuming the story of her grandmother, Adkins-Jackson noted that the concept of aging in place is complicated; tragically, some people are surviving in place because they are unable to plan for aging and thus unable to age in place. Where one is surviving in place dictates where that person receives care. For example, Helen, who is now experiencing dementia, commutes 10 miles outside of her community to receive health care, and her health concerns are often dismissed in these predominantly White care settings. Adkins-Jackson explained that Helen’s experiences with residential segregation; displacement; pollution; occupational segregation; wage theft; and challenges related to food, health care, transportation, and access to social supports created this situation of “surviving in place.” She underscored that this “aging in (dis)placement” has occurred for hundreds of years and continues through the multigenerational determinants that prevent people from accessing the resources that would allow them to age well in place.

In closing, Adkins-Jackson asserted that structural determinants, structural racism, and social determinants are critical to the notion of aging in place; what happens in the present was determined in the past, and our elders who have endured such disparities deserve to age how and where they choose.

FRAMEWORKS FOR AGE- AND DEMENTIA-FRIENDLY COMMUNITY INITIATIVES

Emily Greenfield (Professor of Social Work and Director of the Hub for Aging Collaboration, Rutgers University) opened her presentation with a discussion of conceptualizing communities as a social unit for aging and dementia. She said that communities are defined broadly as connections across a set of people through a combination of shared beliefs, circumstances, priorities, relationships, or concerns, typically formalized through institutions at the local level, such as faith-based and civic groups (Chaskin, 1997). In aging research in particular, communities are often thought to be formed by people with shared social identities who connect across space and time through digital technologies; around specific organizations, such as churches, senior centers, and residential housing settings; or geographically—that is, where they live, work, or play.

Greenfield explained that communities are one of the many contexts in which aging individuals are embedded. Therefore, conceptual models

often place individuals at the center. However, she indicated, theorizing about aging extends beyond the role of the individual, as researchers may be more interested in theorizing on and changing the communities in which individuals live. As a result, a new conceptual framework for community gerontology situates communities in the meso-level context, interacting with micro-level social dynamics and macro-level social contexts (Greenfield et al., 2019). She asserted that adopting this perspective offers new insights into developing frameworks for interventions, as well as into systematically changing micro-level social interactions to improve communities for aging with dementia.

Greenfield underscored that this understanding of how communities both affect people and are affected by people contrasts historical representations of communities by aging and health researchers, in which communities were often described as settings to receive services and as external forces acting on people (e.g., social determinants of health). Instead, she advocated for community-centered approaches to health and aging, especially for people aging with dementia. Community-based social innovations for aging and community-centered approaches to public health view communities as both a target of and an engine for change (South, 2015; Yasumoto & Gondo, 2021). For example, Public Health England’s community-centered approaches to public health concentrate on enhancing a community’s capacity to change social determinants of health, tapping community members’ networks and information channels for health, encouraging multisectoral collaboration on health, and facilitating civic engagement as a means for health (South, 2015). Although not specifically described as community-centered approaches to aging, she noted that several U.S. programs—such as Memory Cafes,2 Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities,3 the Village to Village Network,4 and other age- and dementia-friendly community initiatives—exemplify the principles of these approaches.

Greenfield next turned to a discussion of advancing frameworks specifically for age- and dementia-friendly community initiatives. She noted that the World Health Organization initially developed the concept of age-friendly communities more than 20 years ago by creating a framework of eight characteristics encompassing social, built, and service environments that make cities amenable to aging.5 Public-sector involvement is centered at the subnational level to advance these age-friendly communities. In the United States, the age-friendly national network is supported by American

___________________

2 https://www.memorycafedirectory.com

3 https://aging.ny.gov/naturally-occurring-retirement-community-norc

5 The 8 characteristics are: Community and health care; transportation; housing; social participation; outdoor spaces and buildings; respect and social inclusion; civic participation and employment; as well as communication and information.

Association of Retired Persons (AARP). The concept of dementia-friendly communities first emerged in Japan in 2005, she explained, expanded to the United Kingdom, and began in the United States in the early 2010s—specifically, in Minnesota. Dementia Friendly America,6 a national network of dementia-friendly community efforts supported by USAging, emerged in 2015. She explained that dementia-friendly communities highlight strategies to make local communities more responsive to aging in place for people with dementia, focus broadly on inclusion of and supports for people living with dementia and their care partners, improve design and service of physical infrastructure, and reduce the stigma around aging with dementia.

Greenfield emphasized that age- and dementia-friendly community efforts have developed separately but in parallel. Both initiatives prioritize multisector collaboration across public, private, civic, and academic stakeholders; the joining of place-based communities with global, national, state, and regional networks; and social planning models that convene multisector groups to conduct participatory community assessments, create action plans, implement those plans, and measure progress in meeting goals (Rémillard-Boilard et al., 2020; Scher & Greenfield, 2023). If age- and dementia-friendly initiatives are to serve as interventions for aging in place for people with dementia, she continued, such interventions have to be theorized as complex interventions (Hawe, 2015). She underscored that such interventions help improve the health and well-being of people who are already aging in place (Thomas & Blanchard, 2009). For example, Scharlach (2017) describes “constructive aging” as involving six interrelated processes: continuity, compensation, control, connection, contribution, and challenge. Greenfield noted that these developmental outcomes are of greatest relevance when theorizing about the population health significance of age- and dementia-friendly community initiatives.

Before concluding her presentation, Greenfield highlighted opportunities for research. She remarked that researchers and research funders with a shared vision play an important role across sectors to improve community contexts for aging in place for people with dementia. Research can serve as a tool to:

- help move from programmatic initiatives to community interventions,

- optimize the roles of people with lived experience involved in the work to drive community change, and

- motivate consortiums to support (a) the people in communities who are doing the work, (b) learning and action networks for community leaders, and (c) science for impact, equity, sustainability, and scalability.

___________________

DISCUSSION

Sharing questions from workshop participants, the session chair, Jennifer Manly (Professor of Neuropsychology at Columbia University; planning committee member) moderated a discussion among the session’s three speakers. She asked how dichotomies among people and places—for example, mentally healthy versus cognitively impaired people, or residential setting versus nursing home settings—limit the effectiveness of research.

Oswald replied that researchers in some academic disciplines are more comfortable with poststructuralist thought than others, but he encouraged all researchers to overcome their biases and develop creative new solutions by viewing dementia as a transition. Adkins-Jackson remarked that more voices that represent lived experiences need to be included in the research canon. She also cautioned that diversifying disciplines of study does not automatically result in diverse perspectives. Greenfield added that because current methods are limited in their capacity to honor the complexity of people’s lived experiences, researchers should be humble. As one strategy to address this level of complexity, she advocated for communities to become the units of analysis. Manly observed that dementia experiences differ for each person, which further complicates efforts to understand aging in place for people with dementia.

Elena Fazio (Director of the Office of Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias Strategic Coordination, Division of Behavioral and Social Research, National Institute on Aging) asked how well existing frameworks of neighborhood and community factors that facilitate aging in place fit for people with dementia. Oswald argued that as processes of individuals’ agency decrease over time later in life, processes of belonging might increase. However, this assumption does not apply for people with cognitive impairment or dementia, which creates additional challenges.

Expanding on the discussion of strategies to conduct more effective research, Manly inquired about how people with dementia are included in the conduct, analysis, and presentation of research. Greenfield remarked that she and her team are learning how to do this incrementally and thoughtfully. They recently reviewed a case study of participatory approaches in research on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias and concluded that much variety exists in how researchers are including people with lived experience: few clear norms on how that information should be reported have emerged. She advocated for more transparent processes in publications as well as greater clarity and intentionality in the language used and in the limitations of participatory studies, which could result in a more just and more rigorous use of participatory methods for research.

Adkins-Jackson referenced Andrea Gilmore-Bykovskyi (Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al., 2022), who has published suggestions on how to conduct participatory research, and Northwestern University, which has a mentorship program that pairs a medical student with a person living with dementia. Adkins-Jackson also highlighted the value of providing background information to, having conversations with, and seeking feedback from not only the person with dementia but also the family and caregivers—and obtaining consent from all—when conducting research.

Oswald referenced several relevant studies, including an interdisciplinary study on how to guarantee informed consent processes when engaging people with dementia in research (Haberstroh & Müller, 2017). He also described a study that provides empirical evidence on the best environment for people to receive a dementia diagnosis (Florack et al., 2023), as well as a study about a program in Frankfurt that draws on and expands a program at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that offers a course for people with dementia and their relatives that included museum visits and workshops to maintain and promote social participation and a sense of belonging to the community (Adams et al., 2022).

Terri Lewinson (Associate Professor, Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice) wondered how to encourage people of color to trust the health care system, seek medical care, and be involved in medical research after years of historical wrongs committed against the Black community. Adkins-Jackson suggested offering reparations and restorative justice to initiate healing and serve as a step to mend the relationship before asking people to participate in research.

A workshop participant posed a question about how technology can enable place-making processes in the digitalized world. Greenfield said she expected an increased focus on the use of new technologies to address longstanding issues. For example, the state of New York used public funds to purchase approximately 70,000 voice-operated smart technology devices for people aging in place who are at risk for isolation and loneliness. She underscored the need for cross-disciplinary efforts to develop and evaluate such approaches that could accelerate social change.

Oswald explained that as digitalization continues to expand in Germany, the divide continues to grow between younger generations who are online and older generations who are not. He noted that digitalization affects daily social exchange processes, such as voting or reading a newspaper. Referencing Adkins-Jackson’s presentation, he added that one’s biography, history, and lived experience affect one’s use of technology, especially later in life. Therefore, he said, leveraging technology solutions to enable people to age in place is complex owing to issues of barriers and access. Adkins-Jackson added that technology often exacerbates existing disparities and

inequities, and she advocated for emerging technology efforts to focus on equity at the start of innovation.7

REFERENCES

Adams, A-K., Oswald, F., & Pantel, J. (Hrsg.) (2022). Museumsangebote für Menschen mit Demenz. Ein Praxishandbuch zur Förderung kultureller und sozialer Teilhabe. Kohlhammer.

Adkins-Jackson, P. B., George, K. M., Besser, L. M., Hyun, J., Lamar, M., Hill-Jarrett, T. G., Bubu, O. M., Flatt, J. D., Heyn, P. C., Cicero, E. C., Zarina Kraal, A., Pushpalata Zanwar, P., Peterson, R., Kim, B., Turner 2nd, R. W., Viswanathan, J., Kulick, E. R., Zuelsdorff, M., Stites, S. D., . . . Babulal, G. (2023). The structural and social determinants of Alzheimer’s disease related dementias. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 19(7), 3171–3185. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13027

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 52, 1–26.

___. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164–180.

Buse, C., & Twigg, J. (2016). Materializing memories: Exploring the stories of people with dementia through dress. Ageing and Society, 36(6), 1115–1135.

Chaskin, R. J. (1997). Perspectives on neighborhood and community: A review of the literature. Social Service Review, 71(4), 521–547. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30012640

Crear-Perry, J., Correa-de-Araujo, R., Lewis Johnson, T., McLemore, M. R., Neilson, E., & Wallace, M. (2021). Social and structural determinants of health inequities in maternal health. Journal of Women’s Health, 30(2), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8882

Cutchin, M. P. (2018). Active relationships of aging people and places. In M. W. Skinner, G. J. Andrews, & M. P. Cutchin (Eds.), Geographical gerontology: Perspectives, concepts, approaches (pp. 216–228). Routledge.

Diener, A. C., & Hagen, J. (2022) The power of place in place attachment, Geographical Review, 112(1), 1–5.

Dooley, J., Webb, J., James, R., Davis, H., & Read, S. (2021). Everyday experiences of post-diagnosis life with dementia: A co-produced photography study. Dementia, 20(6).

Duggan, S., Blackman, T., Martyr, A., & Schaik, P. V. (2008). The impact of early dementia on outdoor life: A “shrinking world”? Dementia, 7(2).

Florack, J., Abele, C., Baisch, S., Forstmeier, S., Garmann, D., Grond, M., Hornke, I., Karakaya, T., Karneboge, J., Knopf, B., Lindl, G., Müller, T., Oswald, F., Pfeiffer, N., Prvulovic, D., Poth, A., Reif, A., Schmidtmann, I., Theile-Schürholz, A. Ullrich H., & Haberstroh, J. (2023). Project DECIDE, part II: Decision-making places for people with dementia in Alzheimer’s disease: Supporting advance decision-making by improving person-environment fit. BMC Medical Ethics, 24(26). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-023-00905-0

Gaugler, J. E. (2023). Introductory editorial: Cultivating the formidable legacy of the gerontologist. The Gerontologist, 63(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac166

Gee, G. C., Hing, A., Mohammed, S., Tabor, D. C., & Williams, D. R. (2019). Racism and the life course: Taking time seriously. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S43–S47. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304766

Genoe, M. R. (2009). Living with hope in the midst of change: The meaning of leisure within the context of dementia. UWSpace. http://hdl.handle.net/10012/4500

___________________

7 See the end of Chapter 3 for a summary of this session and the following one.

Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A., Croff, R., Glover, C. M., Jackson, J. D., Resendez, J., Perez, A., Zuelsdorff, M., Green-Harris, G., & Manly, J. J. (2022). Traversing the aging research and health equity divide: Toward intersectional frameworks of research justice and participation. The Gerontologist, 62(5), 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab107

Glymour, M. M., & Manly, J. J. (2008). Lifecourse social conditions and racial and ethnic patterns of cognitive aging. Neuropsychology Review, 18, 223–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-008-9064-z

Gómez, C. A., Kleinman, D. V., Pronk, N., Wrenn Gordon, G. L., Ochiai, E., Blakey, C., Johnson, A., & Brewer, K. H. (2021). Addressing health equity and social determinants of health through Healthy People 2030. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 27(Suppl 6), S249–S257. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001297

Greenfield, E. A., Black, K., Buffel, T., & Yeh, J. (2019). Community gerontology: A framework for research, policy, and practice. The Gerontologist, 59(5), 803–810.

Haberstroh J., & Müller T. (2017). Einwilligungsfähigkeit bei Demenz: Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 50(4), 298–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-017-1243-1

Han, A., Radel, J., McDowd, J. M., & Sabata, D. (2016). Perspectives of people with dementia about meaningful activities: A synthesis. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 31(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317515598857

Hawe, P. (2015). Lessons from complex interventions to improve health. Annual Review of Public Health, 18(36), 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114421

Höppner, G., & Urban, M. (Eds.). (2019). Materialities of age and ageing: Concepts of a material gerontology. Frontiers in Sociology. https://doi.org/10.3389/978-2-88945-863-9

Lewis, C., & Buffel, T. (2020). Aging in place and the places of aging: A longitudinal study. Journal of Aging Studies, 54, 100870.

Li, X., Keady, J., & Ward, R. (2019). Transforming lived places into the connected neighbourhood: A longitudinal narrative study of five couples where one partner has an early diagnosis of dementia. Ageing and Society, 13, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X1900117X

Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Sommerlad, A., Ames, D., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne, C., Burns, A., Cohen-Mansfield, J., Cooper, C., Costafreda, S. G., Dias, A., Fox, N., Gitlin, L. N., Howard, R., Kales, H. C., Kivimäki, M., Larson, E. B., Ogunniyi, A., . . . Mukadam, N. (2020). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet, 396(10248), 413446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

Margot-Cattin, I. (2021). Participation in everyday occupations and situations outside home for older adults living with and without dementia: Paces, familiarity and risks [Doctoral dissertation, Karolinska Institutet]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Mattos, M. K. (2016). Mild cognitive impairment in older, rural-dwelling adults [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburg]. ProQuest Information & Learning. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/78482992.pdf

National Partnership for Women & Families. (2023). Quantifying America’s gender wage gap by race/ethnicity fact sheet. https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/quantifying-americas-gender-wage-gap.pdf

Niedoba, S., & Oswald, F. (2023). Person-environment exchange processes in transition into dementia: A scoping review. The Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnad034

Oswald, F., & Wahl, H.-W. (2019). Physical contexts and behavioral aging. Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.399

Oswald, F., Wahl, H.-W., Wanka, A., & Chaudhury, H. (2024). Theorizing place and aging: Enduring and novel issues in environmental gerontology. In M. P. Cutchin & G. D. Rowles (Eds.), Handbook of aging and place. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pace, J. (2020). “Place-ing” dementia prevention and care in NunatuKavut, Labrador. Canadian Journal on Aging, 39(2, SI), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980819000576

Pani-Harreman, K. E., Bours, G. J. J. W., Zander, I., Kempen, G. I. J. M., & van Duren, J. M. A. (2021). Definitions, key themes, and aspects of “ageing in place”: A scoping review. Ageing & Society, 41(9), 2026–2059.

Rémillard-Boilard, S., Buffel, T., & Phillipson, C. (2020). Developing age-friendly cities and communities: Eleven case studies from around the world. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010133

Rhodus, E. K., & Rowles, G. D. (2023). Being in place: Toward a situational perspective on care. The Gerontologist, 63(1), 3–12.

Roach, J. (2016). ROOTT’s theoretical framework of the web of causation between structural and social determinants of health and wellness—2016. Restoring Our Own Through Transformation. https://www.roottrj.org/web-causation

Rowles, G. D. (1983). Geographical dimensions of social support in rural Appalachia. In G. D. Rowles & R. J. Ohta (Eds.), Aging and milieu: Environmental perspectives on growing old (pp. 111–129). Academic Press.

Rowles, G. D. (1993). Evolving images of place in aging and “aging in place.” Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, 17(2), 65–70.

Rubinstein, R. L. (1987). The significance of personal objects to older people. Journal of Aging Studies, 1, 225–238.

Scharlach, A. E. (2017). Aging in context: Individual and environmental pathways to age-friendly communities. The Gerontologist, 57(4), 606–618. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx017

Scher, C. J., & Greenfield, E. A. (2023). Variation in implementing dementia-friendly community initiatives: Advancing theory for social change. Geriatrics, 8(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8020045

Söderhamn, U., Aasgaard, L., & Landmark, B. (2014). Attending an activity center: Positive experiences of a group of home-dwelling persons with early-stage dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 1923–1931.

South, J. (2015). A guide to community-centered approaches for health and wellbeing. Public Health England. https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/1229

Sugiyama, M., Chau, H.-W., Abe, T., Kato, Y., Jamei, E., Veeroja, P., Mori, K., & Sugiyama, T. (2022). Third places for older adults’ social engagement: A scoping review and research agenda. The Gerontologist, 63(7), 1149–1161. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac180

Thomas, W. H., & Blanchard, J. M. (2009). Moving beyond place: Aging in community. Generations, 33(2), 12–17.

Tung, J. Y., Rose, R. V., Gammada, E., Lam, I., Roy, E. A., Black, A. E., & Poupart, P. (2014). Measuring life space in older adults with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease using mobile phone GPS. Gerontology, 60(2), 154–162.

van Gennip, I. E., Pasman, H. R. W., Oosterveld-Vlug, M. G., Willems, D. L., & Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D. (2016). How dementia affects personal dignity: A qualitative study on the perspective of individuals with mild to moderate dementia. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 71(3), 491–501.

van Wijngaarden, E., Alma, M., & The, A.-M. (2019). “The eyes of others” are what really matters: The experience of living with dementia from an insider perspective. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214724

Ward, R., Rummery, K., Odzakovic, E., Manji, K., Kullberg, A., Keady, J., Clark, A., & Campbell, S. (2021). Beyond the shrinking world: Dementia, localisation and neighbourhood. Ageing and Society, 42(12), 2892–2913. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21000350

Wettstein, M., Wahl, H.-W., Shoval, N., Auslander, G., Oswald, F., & Heinik, J. (2015). Identifying mobility types in cognitively heterogeneous older adults based on GPS-tracking: What discriminates best? Journal of Applied Gerontology, 34(8), 1001–1027.

Yasumoto, S., & Gondo, Y. (2021). CBSI as a social innovation to promote the health of older people in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 4970. https://doi.org/3390/ijerph18094970