Applying Neurobiological Insights on Stress to Foster Resilience Across Life Stages: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 5 The BrainBody Connection Between Stress Susceptibility and Resilience

5

The Brain–Body Connection Between Stress Susceptibility and Resilience

Highlights

- Stress affects multiple bodily systems beyond brain function. Early trauma can alter inflammatory cascades, autonomic function, hormone regulation, and microbial communities, thereby predisposing individuals to neuropsychiatric, cardiovascular, and endocrine dysregulation later in life. (Bremner, Gur, Krystal, Montalvo-Ortiz)

- Vagus nerve stimulation could be a promising intervention to improve resilience and physiological regulation. (Bremner)

- Peripheral immune markers, hormonal transport, and blood–brain barrier permeability allow systemic inflammation to impact central processes, raising questions about the complexity of immune regulation and its role in brain health. (Montalvo-Ortiz)

- Stress can alter gut microbial composition, affecting inflammation and neurotransmitter balance—factors linked to psychiatric disorders and the long-term neurodevelopment in infants. Moreover, the microbiome has emerged as a central factor in resilience, with probiotic interventions showing potential to counteract negative effects. (Gur)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

This chapter shifts the focus to the broader physiological effects of stress, examining its influence on cardiovascular, immune, endocrine, and metabolic functions. Deanna Barch highlighted that stress affects nearly every system in the human body, extending beyond its impact on the brain. She noted that the data presented will illustrate how resilience emerges within these systems and how physiological shifts may shape brain and behavioral outcomes. By exploring these interconnected processes, Barch emphasized the importance of a comprehensive approach to understanding stress susceptibility and resilience.

EPIGENETIC REGULATION AND IMMUNE DYSREGULATION IN STRESS-RELATED OUTCOMES

Janitza Montalvo-Ortiz, assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University, described the role of epigenetic mechanisms in trauma-related disorders. She began by explaining that epigenetics refers to modifications on DNA—such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and noncoding RNAs—that alter gene activity without changing the underlying DNA sequence. In DNA methylation, methyl groups attach to specific regions of the DNA (often in gene promoter regions), influencing whether a gene is expressed or is silenced; when present, these modifications usually correlate with decreased gene expression and condensed chromatin (Montalvo-Ortiz et al., 2022). “DNA methylation patterns are established during brain development,” she said, and evidence has shown that “childhood trauma can lead to alterations in DNA methylation causing downstream gene expression changes that may influence long-term health and mental health outcomes” (Parade et al., 2021).

Montalvo-Ortiz introduced data from her study, which integrated psychological assessments, epigenetic profiles, and neuroimaging, to illuminate how early life trauma influences long-term mental and physical health. For instance, her team evaluated the methylation of the PCK2 gene, which encodes the mitochondrial phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase—a key enzyme driving gluconeogenesis, the process that synthesizes new glucose from noncarbohydrate precursors to sustain stable blood sugar levels when carbohydrate

intake is low (Kaufman et al., 2018). PCK2 has been previously linked to an altered methylation pattern that acts as an indirect mediator between childhood trauma and body mass index. Her team focused on OTX2 (orthodenticle homeobox 2), a gene implicated in long-term stress susceptibility, and found that heightened methylation levels predicted higher depression scores among children who had experienced early adversity (Kaufman et al., 2018). Kaufman and colleagues (2018) further linked these epigenetic changes with alterations in neural connectivity—specifically, increased functional connectivity between the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex, regions that play a crucial role in emotion regulation.

Beyond peripheral tissue studies, Montalvo-Ortiz referenced some of Michael Meaney’s work on postmortem brain samples (Lutz et al., 2017). In donors with a history of childhood abuse, discrete changes in DNA methylation were noted in oligodendrocytes—cells responsible for myelin production—accompanied by downregulation of myelin-related genes and structural alterations in the anterior cingulate cortex, which is important in emotional regulation, cognitive processing, and integrating stress responses. Furthermore, genome-wide approaches investigating DNA methylation in trauma-related disorders have highlighted dysregulation in pathways governing the primary conduit between the brain and peripheral stress responses, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, as well as inflammatory processes (Katrinli et al., 2022; Nunez-Rios et al., 2022). Complementary imaging studies using positron emission tomography (PET) have linked lower availability of translocator protein—a microglial marker—with greater post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) severity, while peripheral markers of systemic inflammation like C-reactive protein appear to correlate inversely with central immune activity. Collectively, these observations point to a systemic imbalance in immune function, where PTSD appears to drive peripheral inflammation while simultaneously altering neuroimmune responses.

MATERNAL STRESS, THE GUT MICROBIOME, AND INFANT NEURODEVELOPMENT

Tamar Gur, associate professor at The Ohio State University College of Medicine and endowed director of the Sarah Ross Soter Women’s Health Research Program, focused on the intricate relationship between maternal stress, gut microbiome composition, and infant neurodevelopment. She explained that during stress the immune system, the HPA axis, and the sympathetic nervous system trigger increases in hormone levels in the gut and intestinal motility, which leads to a disruption in the normal balance of gut microbes—a condition commonly referred to as “dysbiosis” (Gur et al., 2017, 2019).

Under healthy conditions, the gut hosts a complex community of beneficial microorganisms that produce key metabolites. One such metabolite, butyrate—a short chain fatty acid—has significant roles in regulating epigenetic processes. Gur highlighted tryptophan, an essential amino acid obtained solely through diet, which is normally metabolized by specific gut bacteria into beneficial compounds that play key roles in neurodevelopment and immune regulation, such as indole-3-acetic acid and kynurenic acid (Galley et al., 2023, 2024). In experimental models, prenatal stress was shown to reduce the presence of key tryptophan-metabolizing microbes, leading to an altered metabolic profile that could affect the function of microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain known to be critical in synaptic pruning and neurogenesis (see Figure 5-1).

Employing a prenatal mouse model approximately corresponding to the human second trimester with chronic restraint stress, Gur’s team demonstrated that even a single episode of maternal stress can set lifelong trajectories in the offspring’s microbiome (Gur et al., 2017). Gur assessed variations in the microbial community between experimental groups, revealing distinct shifts in the microbial composition of stressed mouse mothers compared to controls. In parallel, offspring exposed in utero to maternal stress exhibited increased microglial activation—evident by ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 immunolabeling—in the prefrontal cortex. These neuroimmune changes were further paralleled by deficits in social behaviors and, in female animals, heightened anxiety-like behavior.

Integrating clinical findings, Gur referenced a study where pregnant women with elevated anxiety, as measured by the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale,1 transmitted a microbial signature characterized by reduced bifidobacteria dentium to their infants (Galley et al., 2023). Interestingly, experimental supplementation with this microbe in stressed mice led to reductions in interleukin 6 (IL-6) production by microglia and improvements in social behavior (Galley et al., 2024). Such findings underscore the potential for altered microbial profiles to serve as indicators of stress exposure and risk for adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.

___________________

1 The Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale is a five-item self-report measure designed to evaluate the severity and functional impact of anxiety across various anxiety disorders. It provides a standardized approach for assessing anxiety-related distress and impairment (Campbell-Sills et al., 2009).

NOTES: In this process, the interaction between the gut microbiome, immune cells, and tryptophan metabolism is a key factor. More specifically, maternal stress reduces microbes responsible for metabolizing tryptophan, disrupting key neurodevelopmental processes in the fetus. ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; CO2H = carboxyl group; HPA = hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis; NH2 = amino group; O = oxygen; O- = oxygen anion; SNS = sympathetic nervous system.

SOURCE: Presented by Tamar Gur on March 25, 2025.

CARDIOVASCULAR CONSEQUENCES OF STRESS AND BRAIN–HEART COMMUNICATION

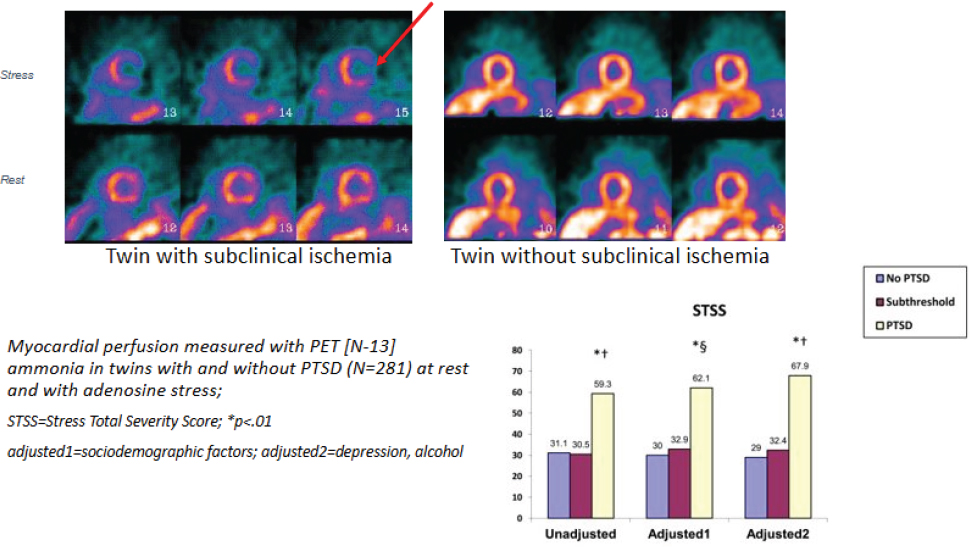

Douglas Bremner, professor of psychiatry and radiology at Emory University and director of the Emory Clinical Neuroscience Research Unit, provided insights into how stress and trauma, particularly in PTSD, are interconnected with cardiovascular function. Using data from studies involving Vietnam-era twin pairs, where one twin was exposed to combat and the other was not, Bremner illustrated that stress may precipitate heart problems such as myocardial ischemia even in the absence of extensive atherosclerotic disease, a heart disease marked by fat buildup in the arteries (Moazzami et al., 2020; Vaccarino et al., 2013, 2021, 2022; see Figure 5-2). PET imaging studies revealed reduced heart-related (myocardial) flow reserve, a measure of the heart’s ability to increase blood flow under stress conditions, in individuals with elevated PTSD symptoms (Vaccarino et al., 2013).

Bremner emphasized that the altered myocardial blood flow could be linked to changes in autonomic function. Specifically, reduced heart rate variability, particularly in the high-frequency range—a reflection of parasympathetic nervous system activity—is associated with stress-induced myocardial ischemia. Additionally, inflammatory markers, notably IL-6, were observed to show dramatic increases following mental stress tasks (e.g., public speaking challenges and personalized trauma scripts; Vaccarino et al., 2021). These findings point to a scenario in which an overactive sympathetic response, coupled with an inadequate parasympathetic counterbalance, may drive both cardiac dysfunction and heightened inflammatory activity.

The connection between the brain and heart is further exemplified by neuroimaging data. In individuals who exhibited stress-induced ischemia, increased activation in the anterior cingulate and rostromedial prefrontal cortex was detected (Moazzami et al., 2020). These regions are known to process emotions and stress, suggesting that abnormal brain responses could serve as biomarkers for heightened cardiovascular risk. Complementary autonomic measures, such as the pre-ejection period, provided further evidence of sympathetic overdrive during stress. Studies exploring vagus nerve stimulation demonstrated that enhancing parasympathetic activity might attenuate these stress-induced cardiovascular responses, as shown by improvements in myocardial blood flow, stabilized respiratory patterns, and reduced levels of inflammatory cytokines (Bremner et al., 2020). Bremner underscored the profound impact of PTSD and stress on cardiovascular health, highlighting autonomic dysfunction and systemic inflammation as critical mediators of disease progression while presenting vagus nerve stimulation as a promising intervention for both psychological and physiological resilience.

NOTES: Myocardial perfusion was measured using PET in twins with and without PTSD, both at rest and under adenosine-induced stress. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; STSS = Stress Total Severity Score.

SOURCES: Presented by Douglas Bremner on March 25, 2025; adapted from Vaccarino et al., 2013. The scans were created by Viola Vaccarino, and the bar chart is from Vaccarino et al., 2013.

DISCUSSION

Early Adversity and Peripheral Health Outcomes

Nadine Burke Harris shared her curiosity on whether individuals who do not meet criteria for psychopathology but were exposed to early adversity might be linked with adverse peripheral outcomes, such as inflammatory cardiovascular or endocrine dysregulation. Bremner elaborated on this point by noting that although he had previously assumed such outcomes were confined to those with PTSD or other mental health conditions, emerging evidence suggests that early adversity may also manifest in adverse pathophysiology among those without overt clinical disorders. Gur described a pilot study involving 36 women from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. In these nonpsychiatric participants, her team observed significant relationships between stress, subtle depressive symptoms, and both changes in specific chemokine levels (e.g., CCL2) as well as shifts in the composition of the vaginal and fecal microbiomes (Rajasekera et al., 2024). Bremner later mentioned collaborative work with Rob Anda of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicated increased cardiovascular risk in broader populations.

John Krystal, chair of psychiatry and the Robert L. McNeil Jr. Professor of Translational Research at Yale University, explained that biological findings can have different implications in psychopathological and nonpsychopathological populations. He referenced studies on Special Forces trainees, noting that while high norepinephrine levels are often associated with pathology in PTSD cases, their meaning depends on accompanying factors, such as neuropeptide Y (NPY) levels (Morgan et al., 2000). Morgan and colleagues (2000) found that resilient trainees exhibited both high norepinephrine and high NPY, suggesting that biological profiles must be interpreted within a broader context when assessing their relationship to psychopathology. Various perspectives pointed to the potential for early life stress to shape peripheral biological and cardiovascular profiles irrespective of psychiatric diagnosis.

Tryptophan Metabolism and Neuropsychiatric Signaling

Kerry Ressler raised a question regarding the role of tryptophan in the broader context of microbiome influences on stress response and if tryptophan could explain some of the individual differences in efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Gur explained that while tryptophan metabolism is likely one among several mechanisms affected by stress, it may represent a major pathway through which peripheral signals influence the developing brain (Verosky et al., 2025). In her presentation, Gur emphasized not only correlations between stress and altered tryptophan metabolism but

also changes in beneficial versus potentially pathogenic microbial populations, especially in historically marginalized populations. Gur presented a nuanced perspective on how tryptophan’s interaction with gut health may contribute to individual differences observed in responses to SSRIs. Using pregnancy-related depression as an example, she reaffirmed her stance that treatment is necessary when indicated, as untreated depression itself can negatively affect neurodevelopment. However, Gur raised an important question about whether SSRI treatment might be less effective in individuals with reduced serotonin tryptophan-metabolizing capacity, noting that 95 percent of serotonin is found in the gut rather than the brain. She suggested this area warrants further investigation. Husseini Manji rounded out the discussion by remarking on emerging therapeutic strategies, including targeted immune modulation, and highlighted that while SSRI treatments may alleviate some symptoms of depression, they often do not normalize the diverse biological imbalances observed in stress-related conditions.

The Implications of Blood–Brain Barrier and Gut Permeability for Resilience

Nadine Kabbani, neuroscientist from George Mason University, inquired about the active transport of tryptophan across the blood–brain barrier and whether developmental changes in blood–brain barrier permeability might create periods of heightened vulnerability. While she was less familiar with the blood–brain barrier, she emphasized the placenta’s complex role in neurodevelopment and invited further exploration. Montalvo-Ortiz expanded on immune system crosstalk, describing three mechanisms by which peripheral inflammatory signals can enter the brain through the blood–brain barrier: direct active transport, leakage through weak barrier regions, and receptormediated transmission. Barch stressed the importance of investigating how stress at different developmental stages affects transport mechanisms and blood–brain barrier function, suggesting further research in offspring. Bremner added insights from single-cell transcriptomic research, noting that vascular endothelial cells show changes in PTSD, including shifts in cell adhesion molecules, which could indicate altered blood–brain barrier permeability in adults.

Complementary to this dialogue, Brian Dias introduced the idea of extracellular vesicles as an alternative mechanism of communication across biological barriers—thus broadening the discussion to consider nontraditional carriers of biological signals beyond immune function and hormone signaling. Montalvo-Ortiz acknowledged the complexity of the question and speculated on how hormones might cross the blood–brain barrier, highlighting the role of HPA-axis activation in peripheral inflammatory signaling. Regarding extracel-

lular vesicles, tiny carriers of molecular signals, Gur highlighted research led by Banu Gumusoglu at the University of Iowa, which examines their role in preterm birth. She noted that severe depression during pregnancy has been linked to preterm birth, a relationship that may or may not be mitigated by antidepressant treatment (Gumusoglu, 2024). Gur suggested that extracellular vesicles could play a key role in transmitting stress-related biological information between mother and offspring. She reflected on previous assumptions in the maternal immune activation field, where it was believed that inflammation in the mother directly led to inflammation in the offspring. However, her research indicates that this is not necessarily the case for stress-related signaling. Instead, she proposed that extracellular vesicles might serve as crucial mechanisms in this process, potentially shaping fetal development and stress susceptibility. Barch underscored the importance of examining these permeability mechanisms developmentally, noting the need for more research on how stress at different time points impacts transport mechanisms and regulatory systems.

Laura Bustamante shared insights from her personal experience with fructose malabsorption and its impact on her mental health and mood, which brought attention to the promise of dietary and probiotic interventions as vehicles for mitigating stress-induced microbiome alterations. Gur pointed out the lack of discussion on gut permeability, expanding the discussion beyond the blood–brain barrier to include gut permeability and placental function. She noted that gut permeability, often referred to in discussions of “leaky gut,” has implications for both individual health and intergenerational effects. Disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease frequently co-occur with psychiatric conditions, raising questions about the interplay between gut permeability, stress, and mental health. Gur pointed out that stress-induced permeability changes may not only affect the individual but could also have consequences for the next generation, potentially influencing neurodevelopmental outcomes. She also referenced research on extracellular vesicles in relation to preterm birth, linking them to maternal stress signaling and the broader question of how biological information is transmitted from mother to offspring.

The Intersection of Inflammation and Mental Health

Andrew Fuligni, professor of psychology and psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, asked about the challenges in assessing neuroimmune functioning across development. He wondered how best to conceptualize healthy versus unhealthy immune states in infants, children, and adolescents when most available models are derived from adult populations. Gur and Montalvo-Ortiz pointed out that measures taken from adult populations

may not directly translate to younger individuals. Montalvo-Ortiz agreed that there is no clear consensus on immune function, even in adults, especially concerning PTSD and developmental psychopathology. She discussed the variability in immune signaling across different biological systems, highlighting inconsistencies in pro-inflammatory markers and neuroimmune suppression in PTSD. She also highlighted the complexity of IL-6, which has both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects, depending on its role in the brain and periphery. As research expands beyond peripheral markers to brainspecific immune function, she emphasized the need for further exploration of these relationships across development. Gur acknowledged the complexity of Fuligni’s question and expanded on the topic by discussing pregnancy as another critical period of immune changes. She emphasized the lack of a clear definition of normal immune function across the lifespan, particularly regarding the microbiome and immune markers. Gur noted that without a full understanding of what constitutes a healthy microbiome, defining immune dysfunction remains challenging.

Herman Taylor observed that the mortality curves for patients with PTSD and stress-induced myocardial ischemia were reminiscent of those seen in studies of post-myocardial-infarction depression. In his remarks, Taylor queried whether interventions in the psychiatric domain might have measurable effects on cardiovascular outcomes and whether these outcomes might ultimately depend on addressing underlying inflammatory processes. Bremner recalled past trials—such as the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study (Writing Committee for the ENRICHD Investigators, 2003)—and acknowledged that interventions for depression have yielded only modest benefits in terms of cardiovascular endpoints. Complementing these clinical insights, Krystal remarked that the relationship between systemic inflammation and mental health is intricate; the presence of depression may sometimes serve as a biomarker of a broader inflammatory state rather than acting as an isolated causal factor. Huda Akil added to the conversation by emphasizing that individual variability in biological responses (including differences in insulin resistance and microbiome composition) could help explain why some individuals are more vulnerable than others to the cascading effects of stress. As a unifying theme, Gur invoked a Greek phrase that links mental and physical well-being, “a sound mind and a sound body,” suggesting that a harmonious balance between the two is critical even if such a balance is challenging to achieve in practice.

Montalvo-Ortiz highlighted the rapid advancement of bioinformatics tools in helping researchers analyze and interpret complex datasets. She discussed efforts to disentangle cause from consequence in the role of inflammatory signaling in PTSD, citing studies that use polygenic risk scores of inflammatory markers from large datasets like the UK Biobank. She also noted that

methods such as Mendelian randomization2 are being employed to explore mediation mechanisms and causality. As data and analytical tools continue to evolve, Montalvo-Ortiz emphasized their potential to enhance understanding of the biological factors underlying stress susceptibility.

Workshop participants discussed the profound interconnectedness of stress with physiological systems, demonstrating its impact on neuroimmune function, cardiovascular health, metabolism, and microbiome regulation. As research advances, integrating perspectives from psychiatry, immunology, and neuroscience may help develop targeted interventions that promote resilience across both mental and physical health.

___________________

2 Mendelian randomization is a research method that uses genetic differences people inherit from their parents to help scientists determine whether certain environmental factors directly cause health effects rather than just being associated with them. This approach helps researchers make stronger conclusions about cause and effect in health studies (Smith and Ebrahim, 2003).