Issues at the Intersection of Engineering and Human Rights: Proceedings of a Symposium (2025)

Chapter: 8 Participation and Inclusion in Engineering Decision Making

8

Participation and Inclusion in Engineering Decision Making

The first panel of Day 2 examined methods for and the importance of early and continuous community participation in engineering decision making. The panel emphasized that meaningful participation not only is important in terms of inclusion and responsibility but also improves engineering results. Amy Smith, Founding Director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) D-Lab and Senior Lecturer of Mechanical Engineering at MIT, discussed D-Lab’s motivation, ethos, and its work to facilitate community engagement. Michael Ashley Stein, Co-Founder and Executive Director of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, spoke about disability rights, how engineers can and should design with people with disabilities rather than for them, and why co-development of ideas leads to better engineering outcomes. John Kleba, Full Professor of Social Sciences at ITA, the Institute for Aeronautics Technology in Brazil, discussed his work leading the Citizenship and Social Technologies Laboratory’s efforts on engaged engineering and participatory methodologies in a Latin American context. Following the presentations, Smith moderated the ensuing discussion with the symposium’s participants.

THE INTANGIBLE BENEFITS OF PARTICIPATION AND INCLUSION

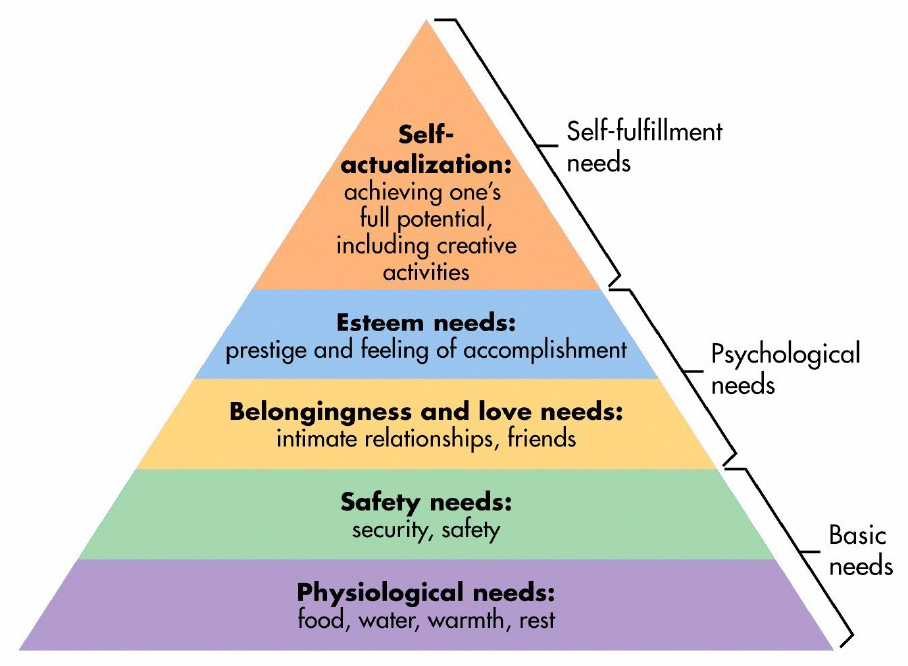

Amy Smith began the session with an interactive activity in which audience members used one word to describe their feelings after making something, whether that thing was a part of a large engineering project or an Ikea bookcase. Answers included joy, agency, self-esteem, and pride, each of which Smith described as intangible benefits derived from the process of problem solving—rather than the products. Such benefits, she said, are important when thinking about human rights and the things people need to live fulfilled lives, which range from physiological and safety needs to psychological and self-fulfillment needs (Figure 8-1).

SOURCE: Smith and Thompson, 2023, Figure 1. Presented by Amy Smith on November 19, 2024 (Smith slide 4).

Using technology, said Smith, often satisfies many basic needs, but designing and creating technology can satisfy higher-level needs. For example, technology design usually occurs in teams, so the design process enables the building of relationships with colleagues as well as the creation of something. “So, when we talk about inclusion and participation in engineering decision-making, I think that it is incredibly important for us to think about the process of design and engineering as well as the products of design and engineering,” said Smith. “Because I think that is fundamentally where a lot of the transformation happens.” Smith referred to the right to be creative,28 which we do not want to take away from people, because exercising that right can enable feelings of accomplishment, pride, joy, and agency. In that regard, the right to be creative—and the intangible benefits that come from it—provides a framework for understanding the value of participation in engineering.

Smith said that in the context of engineering decision making, who is making decisions and who benefits from those decisions must be considered. Being included and participating in the creative problem-solving process can lead to personal transformation that can help combat a

___________________

28 Article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states, “The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to respect the freedom indispensable for scientific research and creative activity.” See https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights.

sense of dependence that many people, such as refugees and those affected by conflict and crisis, might feel because of the aid they receive.

Too often, said Smith, engineers believe they have addressed inclusion and participation if they have spoken with people to understand their problems and to solicit feedback on the solution the engineers created. Smith offered an alternative framework for thinking about types of participation and possible roles of stakeholders. This framework situates participation into three categories: consultation, partnership, and leadership. Consultation offers end users the opportunity to provide information, share opinions, and give feedback through a one-way flow of information, such as a survey, a two-way flow of information, such as a focus group, or an iterative process. Partnership provides end users with an equal role in problem-solving and decision-making authority, through collaboration or co-creation. Leadership allows end users to direct the process and direction of the project, such as through empowerment or ownership. “Frequently we’re limited to the learn and test side when we think about participation, but the imagine and create side is such an important part to engage people in participation,” said Smith. For Smith, problem solving with a community has four components: learning about a problem, imagining what the solution might be, creating the solution, and getting feedback (Figure 8-2).

SOURCE: Presented by Amy Smith on November 19, 2024 (Smith slide 15).

In South Sudan, Smith collaborated with the local Youth Social Advocacy Team29 on a project to build resilience and social cohesion by engaging people in the design process. By conducting community design trainings and establishing maker spaces, the MIT team helped to

___________________

develop a local innovation ecosystem in which people could work together on projects that improve their lives. Project participants were from different tribes, some which were in conflict with one another. To Smith, this project exemplifies the power of inclusion and participation, as reflected by quotes from the participants:

- “I felt happy and proud of myself for having developed a wheel cart, some of my friends asked me where I got it from, I told them that my team and I developed it and they were shocked and proud of the great work.”

- “In fact, I met a lot of friends from here where we have sat and eaten together. Some of them I used to see… as enemies, but now we are tight friends, and [it] is the CCB [Community Capacity Building training] that did that.”

As a final comment, Smith challenged the engineers attending the symposium to think about who is doing the problem solving and what benefits they are accruing. “Are you the only one getting the joy of creativity or is that spread throughout the people who are experiencing the challenge themselves?” she asked.

NOTHING ABOUT US WITHOUT US

Michael Ashley Stein said that if he had to describe the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in one sentence, he would use the slogan of the international disability rights movement: Nothing about us without us. “Do not make decisions for us. Do not plan our lives out. Do not create legislation, policies, and day-to-day existence without us being part of it,” explained Stein. This attitude applies not only to ableism and paternalism but also to situations involving gender, race, sexuality, and so on, Stein said.

Stein stated that people with a disability account for approximately 15 percent of the global population, or 1.3–1.5 billion people (World Health Organization, 2023). However, said Stein, people with disabilities have generally been excluded from international treaties and human rights mechanisms. Even when disability is mentioned, it is usually at the bare minimum, according to Stein. For example, the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child merely states that children with disabilities should not be discriminated against and that they should be included in schools to the extent possible. The CRPD directly addresses participation and inclusion, but Stein emphasized that the participation must be meaningful. Determining how to implement and apply the principles of the CRPD in engineering practice or any other context requires gathering together members of impacted populations for a discussion, which happens, but rarely, according to Stein. As an example, he cited a September 2024 workshop that he conducted with the joint research wings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank on climate change. Stein pointed out the exclusion of disability from national-level climate programming, which led to a several-hour discussion on ways to effect change while protecting the rights of people with disabilities who will be disproportionately challenged by climate change. He further noted that people with a disability are overrepresented in fatalities and health risks due to fires and extreme heat, citing examples from Australia and British Columbia (British Columbia Coroners Service, 2022; Coates et al., 2022; Stein et al., 2024). Despite this fact, people with disabilities, according to Stein, are systematically excluded from discussions about climate policy and solutions. These conversations—which can lead to disability inclusive co-design—are crucial for effecting change, said Stein. “We have toolkits that are published, we have guidance notes, but we don’t actually have the sort of really nuts and bolts, no pun intended, kind of how do you implement rights?”

Stein cited the “climate justice” approach to policy making, which views people with disabilities as change agents and knowledge holders, makers, and doers. This approach lends itself to co-designing climate-responsive solutions alongside people with disabilities, which helps ensure that those solutions will be inclusive, desired, functional, and intuitive. “When we don’t think about the group, we don’t include them,” said Stein. For example, charging stations that people with disabilities cannot reach, hybrid and electric vehicles that are silent and pose a danger to those who are blind, and all-digital appliances that lack the tactile feedback of “old-fashioned” dials, result from a failure to include people with disabilities in the design and problem-solving process, which often leads to costly retrofitting.

When Stein hears community leaders argue that the disability community is too diverse to accommodate, he challenges them by asking whether they believe that all women have the same needs, highlighting the flaw in using “diversity” as an excuse to not accommodate people with disabilities.

Following the “nothing about us without us” mantra is a matter of not only human rights, decency, and ethics, said Stein, but also efficiency. “Nobody knows their lives as well as the actual stakeholders,” said Stein, and retrofitting is almost always more expensive than designing accessible solutions from the start. He added that inclusion and participation create significant opportunities to design technologies that are inclusive, accessible, assistive, and responsive to the local context.

ENGAGED ENGINEERING

John Kleba explained that he works to effect social change by rethinking engineering practice through what he calls “engaged engineering,” referring to sociotechnical movements and initiatives that consider themselves to be agents of transformation. He asked, “what if the social groups you work with don’t have the same conception and expectation about participation and inclusion as we do?” and referenced a required course at ITA that addresses “citizen formation,” in which engineering students work on projects with various partnerships, including cooperatives and social movements.

Some classwork involves interactions with students at local schools. Kleba stated that nearly half of those local students face economic hardships that have caused them to disengage from educational and job opportunities. By contrast, ITA’s engineering students generally come from more economically privileged backgrounds. When ITA students work with the local schools, a “clash of cultures and expectations” can result. Critical in these situations, said Kleba, is striving for a balance between each project participant’s values and lived experiences. While engineering students often value high technical proficiency, for example, local students seem to engage better with novel and creative undertakings and speak highly of activities such as field trips. Although such activities may seem trivial to some people, they ignite enthusiasm and scientific curiosity among the students.

Kleba emphasized that recognizing students’ unique talents is also a key to fostering participation among students facing barriers to engagement, such as using their illustrations in a project to co-design a technical manual. This approach goes beyond training technical skills—it supports emotional and cognitive shifts to empower students and reinforce the concept that everyone is entitled to equal treatment as citizens.

Kleba described strategies to incorporate human rights principles into his technical projects, such as collaborating with social movements, emphasizing empowerment and

decolonial perspectives, and exploring participatory mapping initiatives. He shared an example of a map that tracks attacks against Indigenous communities30 utilizing satellite technology to provide a reliable overview of issues such as violence, arson, deforestation, and oil exploitation. Kleba also cited the work of TECHO,31 a nonprofit based in several Latin American countries that focuses on infrastructure and implements participatory methodologies to fight extreme poverty in favelas, or informal settlements. TECHO works to empower communities to self-organize and utilizes cartography to inform efforts to secure their rights to education, health services, and adequate and safe housing, especially in areas threatened by climate change, including heavy rainfall and extreme heat.

DISCUSSION

A symposium participant asked Stein for more information on the costs of integrating accessibility features at the onset of a project versus retrofitting. Stein stated that including such features at the onset adds less than 1 percent to the total cost of the project (Steinfeld, 2005), but the cost of retrofitting depends on what needs to happen. Installing an elevator shaft in an existing building, for example, will likely be more expensive than including it in the original design. Stein added that rigorous cost-benefit analysis has yet to be done on this topic and that the World Bank is likely the only entity currently equipped to undertake such a study.

Building on Stein’s comments about inclusive design and retrofitting, Smith discussed the adoption, rejection, and re-purposing of technologies by communities. She noted that most humanitarian aid organizations measure success based on the number of technologies that have been distributed rather than the number that have been adopted and used. As an example, she noted one study that suggests that less than two percent of the solar cookers distributed in a Burkina Faso refugee camp were used to cook food one year after distribution (Troconis, 2017). A more common use in areas with thatched huts is to turn the solar cooker upside down and use it to cover the top of the roof to prevent rain from entering the house.

Sometimes, said Smith, people resist adopting technologies that are new to them. A colleague’s study showed that simply exposing a community to water treatment technologies before introducing them makes them more trusted when implemented in a relief situation. She wondered whether involving people in the process of creating one relevant technology would make them more likely to adopt other technologies implemented in the future.

When asked about the role of engineering in addressing human rights issues where the root problem is political, Smith replied that involving people in the problem-solving process can provide some control in a political situation. Certainly, she added, that approach is not sufficient—political constraints lie far beyond the capacity of simple design projects to address—but it can alleviate some of the challenges posed by an authoritarian regime. In her work, she tries to hold co-creation sessions that include nongovernmental organizations and people from different ethnic groups so that they can better hear each other’s voices and understand each other’s challenges.

Smith briefly described a project organized by her colleague John Jal Dak, Executive Director of the Youth Social Advocacy Team in Uganda. Dak’s community-based and refugee-

___________________

led organization assembled youth from different tribes in a refugee camp to create a radio station to help combat conflict due to the spread of misinformation within the camp. Here, Dak is building off the confidence these youth have developed through their co-creation of simpler technologies, such as a wheel cart or cassava processing, to tackle the design process for a more systemic and larger challenge. She noted that people in these camps are now considering how they can design things to help address gender-based violence.32

An attendee asked whether any for-profit companies are designing from a human rights perspective. Panelists replied that some for-profit organizations are driven by a social mission. Smith noted that several of her students have started for-profit organizations to address poverty-related challenges through market means. She believes that some larger for-profit organizations engage well with end-users. She explained that Unilever has tried to respond to the needs of people living in poverty by, for example, offering its products, such as shampoo, in individual sachets so that people who cannot afford a full bottle can still access the product.

Smith also commented that people often become engineers because they enjoy being problem solvers. However, engineers should have a mindset shift and realize that, in some situations, it may be more appropriate to be a facilitator of the problem solving rather than the actual problem solver—particularly when working with stakeholders who are traditionally marginalized. Engineers, according to Smith, should still value their own contributions, but not overshadow the process. “I think it is incumbent on the engineers to think about what their role in problem solving is, not take themselves completely out of it, but make sure they bring people into it,” said Smith. “Hence the importance of inclusion and participation in the engineering process.” Kleba added that engineers should study ethnocentric bias and positionality to help them understand that what is obvious to one person may not be obvious to another. This is one reason why local or indigenous knowledge must be incorporated into the design process.

When asked about the lessons she learned when developing D-Lab’s community-based design trainings, Smith said that participants should “choose the problems that they’re solving instead of being told what the problems are for them to address.” Even though this approach complicates the curriculum and problem identification processes, Smith stated, “I think is one of the things they value most about the program.” Another takeaway is the need to move away from use of the term “failure” during the design process, because learning from mistakes is simply a part of the process and not a failure. Kleba stressed the importance of conveying to students the need to adapt constantly to challenges that arise during the design process, and of being cognizant of the words one uses and how they might be interpreted in different contexts. For example, he has found that Indigenous people tend not to like the word “inclusion” because they believe it means assimilation into the dominant Western culture and erasure of their heritage. Learning about the context in which you are working, according to Kleba, is essential to co-constructing sound solutions. Stein added that engineers should speak plainly, clearly, and without jargon, particularly when working with people with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities or for whom English is not their native language. Most important, said Stein, is to be “the conduit rather than driver” and listen to people with humility. “We serve these communities, and we do so with great joy, but we serve these communities.”

___________________

32 See, for example, https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/working-group/iasc-guidelines-integrating-gender-based-violence-interventions-humanitarian-action-2015.