Issues at the Intersection of Engineering and Human Rights: Proceedings of a Symposium (2025)

Chapter: 5 Addressing Inequalities in Public Infrastructure

5

Addressing Inequalities in Public Infrastructure

The symposium’s fourth session explored how public infrastructure and policies for its implementation can give rise to disparities among communities and how engineering through a human rights lens can help reduce those disparities. Kimberly Jones, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Associate Provost at Howard University and Chair of the Environmental Protection Agency Science Advisory Board, discussed her work related to water engineering, the effect of access to water on human rights, and potential actions by engineers to improve access and make access more equitable. Bethany Gordon Hoy, Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington, described how community engagement and engineer positionality can enable the design of a more equitable built environment that facilitates environmental justice and climate adaptation. Eric Buckley, Director of Oxygen Engineering and Senior Structural Engineer at Build Health International, spoke about infrastructure for health services and its role in supporting a range of human rights and promoting health equity, and the role that engineers play in building high-quality health infrastructure in resource-constrained settings around the globe. Davis Chacón-Hurtado, Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Co-Director of the Engineering for Human Rights Initiative at the University of Connecticut, explained why a human rights framework is useful for engineering and how transportation infrastructure and human rights intersect. Chacón-Hurtado also moderated the discussion that followed the panelists’ remarks.

ADDRESSING WATER INEQUITIES IN PUBLIC INFRASTRUCTURE

Kimberly Jones said that, in 2010, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly deemed access to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation a human right and asserted that everyone should have enough water to support their daily needs within 30 minutes of their home. She added that not only is access to water a human right, but also, because water is a basic human need, it is also essential to the fulfillment and enjoyment of all other rights. Nonetheless, a global water crisis has existed for years, evidenced by the following statistics: As of 2019, more than 800 children die from water-related diseases every day; 1.8 billion people have no on-premise drinking water; more than 100 million people collect untreated drinking water directly from rivers and lakes; over 2.2 billion people lack access to safely managed drinking water services (UNICEF and WHO, 2019); and billions of dollars in revenue are lost from avoidable deaths resulting from lack of access to basic water and sanitation needs (WaterAid, 2021).

Jones noted that even in the United States, despite years of state and federal regulatory action, from 1982 to 2015, 9–45 million Americans receives water from a source that violated the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), and some 63 million Americans have been exposed to

potentially unsafe water more than once during the past decade. In addition, 3–10 percent of U.S. water systems violate SDWA annually. To meet U.S. water regulations, water utilities need to invest an estimated $384 billion, she added. “Despite years of regulations, we still have large percentages of people in this country and around the world who do not benefit from all our excellent engineering and all our science-backed regulations every day,” said Jones. Moreover, said Jones, “the burdens of this water crisis affect communities very disproportionately.”

Citing the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, Jones stated that these situations are often more an issue of implementation than poor engineering. “These are policy decisions driven largely by economics, by how expensive it is to provide adequate infrastructure to pipe water to people’s homes, for example. And so we have to talk about the intersection of engineering and policy and finances and management, because all these things have to align in order to deliver water safely and consistently to these communities,” said Jones. Addressing the resulting inequities requires investing in infrastructure that specifically targets underserved communities and policy reforms that accomplish that task. These policies must go beyond setting maximum contaminant levels or stating best practices, and engineers should be “really thinking about how we can set these policies so that water can be affordable and it can be reliable and it can be safe.”

Also critically needed, said Jones, are community-led initiatives and capacity building that includes providing training and resources for sustainable water management and upskilling members of communities so that there are professionals who can work together in their communities to ensure their water systems remain safe. Community engagement, according to Jones, is essential to conversations about designing solutions. “We really need to bring those in a community who are going to be impacted by this at the table in the beginning to have these conversations,” she said. Investments must be strategic to ensure that they reach those affected communities, and progress needs to be monitored over the long term because the necessary solutions will not be quick. “We have to be ready to stay, invest, and continue to work in these communities,” said Jones.

ENGINEERING IN CONTEXT

Bethany Gordon Hoy began her remarks by discussing a case study examining water and sanitation utilities for climate refugees in Germany (Kaminsky and Faust, 2017). This study explored the question of when infrastructure is a right versus a service. According to Gordon Hoy, the study’s authors described the responses as “deeply contextual,” and respondents were willing to provide free water and wastewater services for displaced persons entering Germany for approximately 2.9 years. Contextual factors in this case included existing policy and system capacity to meet demands, and whether the necessary infrastructure was already present. Other factors included an awareness of any historical context, the positionality of the decision makers, and the sense of community, all of which led to effective community engagement. Gordon Hoy said that although community engagement is not a space in which engineers are typically comfortable working, it is important to start moving in that direction.

Understanding the historical context, said Gordon Hoy, matters for equitable decision making. For example, knowledge of racial history affects perceptions of systemic racism (Bonam et al., 2018; Nelson et al., 2013). “As engineers, it is important for us to educate ourselves on the history of the places we are going to,” said Gordon Hoy. She has found that when participants received a racial history context that they deemed relevant, they distributed climate adaptation resources differently than participants without that context (Gordon et al., 2023).

Gordon Hoy explained that positionality—the social and political context that shapes a person’s identity—is not a new concept, but one that engineers would benefit from having a deeper understanding of. When she introduces this concept to her engineering students, they often retort that all of their decisions are quantitative and not affected by their identity. She responds that they may not see certain aspects of their social, political, and cultural identity as relevant to engineering because these aspects align with existing systems of power and are therefore normalized. Meanwhile, those same systems can create challenges or negative impacts for others.

Once someone has identified the aspects of their identity that may influence their engineering decision making, they should engage in self-reflection, a concept known as reflexivity. Reflexivity, said Gordon Hoy, involves questioning who one is as an engineer and how one’s positionality influences one’s work (Jamieson et al., 2023). Also important, she added, are accountability and reciprocity, or acknowledging and compensating the expertise of lived experience (Kovach, 2021). These concepts are important when working with communities and for acknowledging the different types of expertise essential for climate adaptation and human rights. They move engineers from a position of needing to maintain their credibility by holding power to one that builds relationships and trust with communities. However, said Gordon Hoy, just as engineers prepare themselves to address inequities, they must prepare their organizations to practice systemic equity. Systemic equity, she explained, requires distributive equity—the fair administration of resources—along with procedural equity regarding relevant policies and recognitional equity, or addressing the cultural needs of those who are marginalized systematically (Bozeman et al., 2022). Without all three of these components, systemic equity cannot be achieved.

BUILDING THE FOUNDATION OF GLOBAL HEALTH EQUITY

The World Health Organization, said Eric Buckley, has stated that health equity is achieved when everyone can attain their full potential for health and well-being, which he believes infrastructure can play a large role in accomplishing. “Your geography should not determine your access to health care, whether you are based here in the United States or anywhere else across the world,” said Buckley.

Infrastructure enables health care, he said, by being the backbone of the ability to deliver care. In his work assessing hundreds of facilities around the world, he has found that inadequate infrastructure is a primary barrier to the ability to deliver care and the primary barrier to patients accessing care. Infrastructure, said Buckley, includes the structural integrity of a facility, its sanitation system and access to clean drinking water, and the roads and transportation system connected to the facility that enables both patients and necessary supplies to get to the facility. Another significant barrier to delivering care is a facility’s access to reliable, safe, high-quality, and sufficient electricity. Buckley questioned, “Can the patients within the community and the community members get to the facility to receive treatment? Are the roads passable? And in the same sense, can the materials, resources, equipment get from where they need to be to the hospital to be able to build and provide the services for those facilities?”

Buckley explained that his organization’s team includes architects; structural engineers; civil engineers; mechanical engineers; plumbing, electrical, medical gas engineers; construction management professionals; and global health professionals working in more than 18 countries. Together, these experts bring their varied experiences and perspectives to bear on developing

appropriate and sustainable solutions for a given context and problem. Sustainability, he explained, encompasses both the climate aspects of sustainability as well as the sustainability of a facility and its operations once a project is completed, which includes local training and capacity building.

As a final comment, Buckley emphasized that engineers are in a unique position to advance health equity and health care access. “We have the responsibility to design for those outcomes, and every infrastructure decision is a health care decision, and every health care decision is a human rights decision,” said Buckley. “The link between engineering and human rights, certainly when it comes to health care access and health equity, is very direct.”

A HUMAN RIGHTS-BASED APPROACH TO ENGINEERING

Davis Chacón-Hurtado said that although engineers may think some of their work affects issues such as forced labor or inadequate access to safe drinking water, they struggle to see a direct connection between these human rights challenges and their daily responsibilities. In response, he and his colleagues have developed a framework for engineering for human rights that highlights “actionable things that as engineers, we can actually control, that we can actually do” to protect and fulfill human rights. The five principles of engineering for human rights upon which this framework is based include distributive justice, participation, consideration of duty bearers,15 accountability, and the indivisibility of rights16 (Chacón-Hurtado et al., 2024).

A human rights-based approach benefits the field of engineering in several ways, said Chacón-Hurtado. First, it provides new language to describe the work that engineers are already doing and a framework for ensuring that engineering decisions do not violate human rights. In addition, it improves public awareness and understanding of engineering, as well as recruitment and retention of students in engineering education. Regarding engineering education, Chacón-Hurtado educators must show students how a preventive approach, remedial approach, and proactive approach to engineering design are linked to human rights. A preventative approach focuses on preventing rights violations. A remedial approach considers actions that engineers can take, such as performing forensic work, to help remedy rights abuses. The proactive approach, according to Chacón-Hurtado, is the most important and involves exploring how engineers can actively work to fulfill human rights

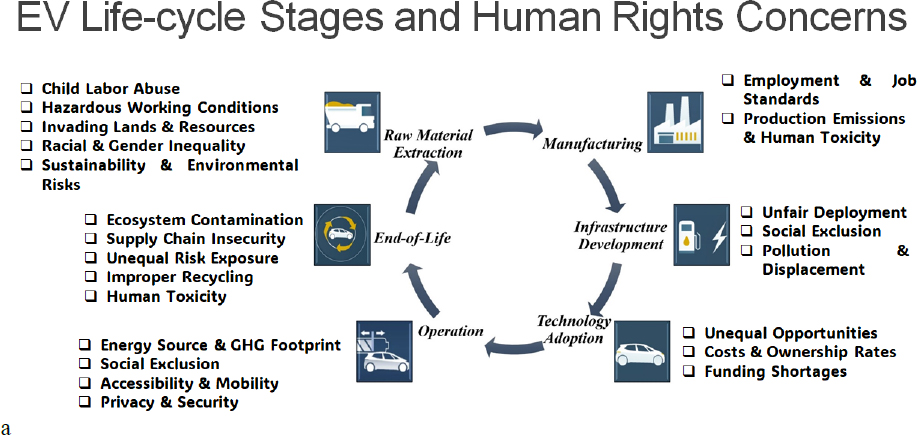

Getting engineers to think about the potential effects of their activities on human rights moves them beyond the simple designing and release of a product into the public domain. By employing the concept of “life cycle thinking,” engineers can contemplate how each stage of design and implementation could be associated with a human rights violation. As an example, Chacón-Hurtado discussed the electric vehicle revolution from a human rights perspective (Figure 5-1) (Rouhana et al., 2024). Considerations include the use of child labor in raw material extraction, inequitable deployment of charging stations, disparate opportunities to purchase an

___________________

15 Duty bearers are “[t]hose actors who have a particular obligation or responsibility to respect, promote and realize human rights and to abstain from human rights violations” [https://www.unescwa.org/sd-glossary/duty-bearer].

16 The indivisibility of rights may be thought of as the principle that all human rights are equally essential and cannot be separated or prioritized one over another.

electric vehicle, and how electric vehicles might or might not benefit some communities in terms of environmental justice.

SOURCE: Adapted from Rouhana et al., 2024 (Figure 3; published under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 license); Chacón-Hurtado slide 15.

Chacón-Hurtado offered two important questions to ask: “Does an infrastructure investment risk violating human rights for the affected community?” and “Will that community will truly benefit from the interventions engineering can bring?” Answering these questions is one way he believes a human rights framework can be useful.

DISCUSSION

The discussion opened with a symposium participant commenting that at a recent conference on water and health, they heard repeatedly that framing water as a human right is negatively impacting the sector. The concern is that people expect their water system to function without additional investments for maintenance, because they consider access to water to be a human right. Jones replied that she understands the rationale for that opinion, but, the fact is, water infrastructure is expensive and is subsidized by the tax base. As a consequence, areas that are of low socioeconomic status, are rural, or have a limited tax base often struggle to maintain their water systems or comply with new regulations and frequently experience SDWA violations. “I do not think your community’s access to safe drinking water should be based on how much money is in that community, but that is very much what we see,” said Jones. Gordon Hoy added that the water community—including engineers—must figure out how to communicate to the public the responsibilities to care for others in their community, especially in the United States.

In response to a participant’s comment that they understand how water and a clean environment are basic human rights, but not how transportation is a basic human right, Chacón-Hurtado explained that transportation is considered an “instrumental right.” Instrumental rights are not necessarily fundamental rights themselves, but they enable the fulfillment of fundamental rights. As an example, he explained that engineers can help promote civil and political rights,

such as the right to privacy or the right to vote, by building the infrastructure, such as secure voting equipment, necessary for the fulfillment of those rights. The engineers in this case are not necessarily protecting the right to vote directly, but they are contributing to the infrastructure necessary to realize that right. According to Chacón-Hurtado, working on instrumental rights17 is often how engineers can contribute toward the fulfillment of fundamental human rights.

A participant asked about opportunities for current engineering professionals to move into more human rights-oriented roles. Buckley replied that UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations such as Engineers Without Borders and Build Health International are involved in global infrastructure projects that would benefit from the input and technical capacity of engineers. He suggested that the participant contact one of those relevant organizations or agencies whose work aligns with their interests.

When asked how to integrate human rights principles into one’s work, Jones said it takes intentionality. For example, most engineers do not think about working with the community that will be affected by their project, and yet studies have shown that working with the community improves project design (Acero et al., 2024). “Educating the next generation of engineers to really understand this and take this on as a way that they do their work will be a huge step, in my opinion, in the right direction in terms of really engaging those communities at the front end,” she said.

Chacón-Hurtado addressed a question about the difference between a human rights–based approach to engineering and universal design, that is, the design of products and systems that are accessible and usable by people of all abilities and backgrounds without the need for adaptation or specialized design. He clarified that engineering for human rights is not intended to replace universal design or any other framework. “These are not competing frameworks,” said Chacón-Hurtado, “They are actually related. And human rights could be included in any of these other frameworks.”

___________________

17 Instrumental rights, such as the right of access to technology, are those rights that are integral to fulfilling other primary rights, such as the right to education (Chacón-Hurtado et al., 2024).