An Artificial Intelligence Code of Conduct for Health and Medicine: Essential Guidance for Aligned Action (2025)

Chapter: 6 The Components Required to Advance Responsible AI

6

THE COMPONENTS REQUIRED TO ADVANCE RESPONSIBLE AI

Promoting positive change at scale in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to impact health, health care, and biomedical science is challenging, in part due to the multitude of interacting activities and stakeholders. Advancing successful development, implementation, and sustained use of trustworthy health AI will require careful coordination and consideration of critical elements and how they work together. Identification of activities that are amenable to collaboration, consolidation, and centralization is warranted to ensure both efficiency and quality of outcomes.

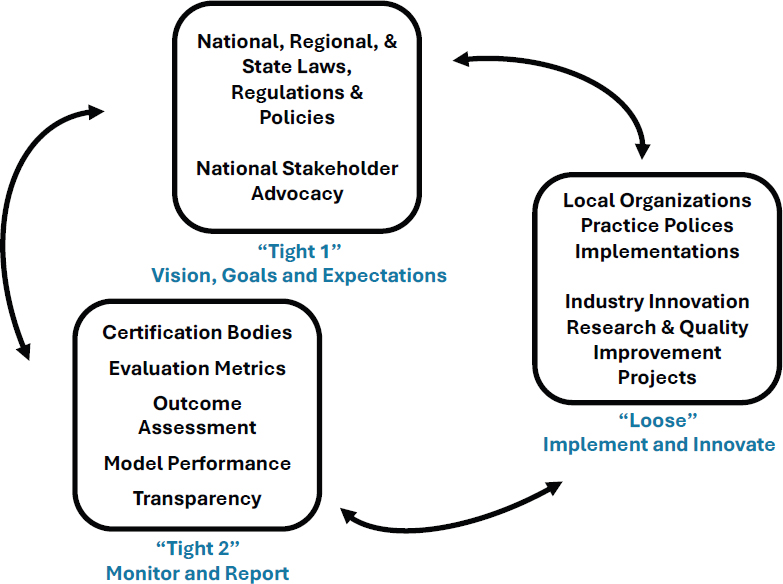

Caldwell and colleagues’ model for leading change at scale provides a useful organizing framework (Caldwell et al., 2005). The Tight-Loose-Tight leadership model describes how change can be effectively propagated through complex systems while maintaining flexibility, supporting a shared ownership, and ensuring stakeholder engagement at all stages. This model is particularly relevant to advancing responsible AI in the health sector. By design, the Tight-Loose-Tight model balances innovation and control, encourages collaboration and builds trust, and supports an iterative, dynamic, and scalable approach that is needed for emerging technologies subject to multilevel governance. The stages of the model are depicted in Figure 6-1 and are described here in more detail.

- Tight 1: Define Vision, Values, Goals, and Expectations: This portion of the model is focused on aligning vision and values through a shared set of principles and commitments (such as the Code Principles and Code Commitments) and on establishing clearly defined goals and expectations as well as desired outcomes and approaches. In the context of health AI, it is driven by key stakeholders, including policy makers, technology firms, health leaders, and various advocacy groups, toward the development and alignment

SOURCE: Conceptually adapted from Compton-Phillips, 2019.

- of principles, laws, regulations, and standards adopted to reflect desired health outcomes in the context of societal norms and needs.

- Loose: Implement and Innovate: This portion of the model addresses the implementation of the goals and vision and the translation of the principles into practice in the context of the laws, regulations, and standards established in the initial phase (Tight 1), with the implicit expectation that testing, adaptation, and flexibility will be necessary to address the local context. In the context of health AI, testing of models, local governance, implementation support, research innovation, supports for new technology, and public–private partnerships are included in this phase. It is important that flexibility of thought, practice, and execution be promoted where possible, if fidelity to the overarching requirements described in the Tight 1 phase is to be maintained and conscious attention to standardization in the Tight 2 phase occurs as well.

- Tight 2: Monitor and Report Outcomes: This third aspect of the Tight-Loose-Tight model is about assessing the degree to which the first two phases have produced the intended outcomes. It represents a more standardized approach to establishing the measurable outcomes and metrics for the process. This phase is focused on assessing whether the health AI processes, tools, and workflows have met the pre-established vision and goals and align or comply with the governing principles, laws, and regulations, including local policies and procedures. It is important that these are reproducible, measurable, transparent, and interpretable, so that all stakeholders involved in the use of health AI understand whether the intended use was achieved.

TIGHT 1: VISION, VALUES, GOALS, AND EXPECTATIONS

Alignment of Health Care AI Principles, Guidelines, and Frameworks Nationally

Internal alignment and coordination on health AI strategies, policies, and relevant regulations across federal agencies are all well underway. As previously noted, in July 2024, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced a reorganization designed to “streamline and bolster technology, cybersecurity, data, and AI strategy and policy functions” (HHS, 2024b). This reorganization addressed the decentralization of AI policy and operations responsibility, which had been jointly managed by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), the Assistant Secretary for Administration, and the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response. A new role of Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy (ASTP) and ONC was established to consolidate these functions and to provide centralized “oversight of technology, data, and AI policy and strategy” (HHS, 2024b). ASTP ONC established an Office of the Chief Technology Officer, which is responsible for overseeing “cross-agency technology, data, and AI strategy and policy” and includes the Offices of the Chief AI Officer, Chief Data Officer, and Digital Services (HHS, 2024b). This internal alignment is an important step to ensuring consistency regarding vision, values, goals, and expectations for health AI across the federal government.

The AI Code of Conduct (AICC) Code Principles and Code Commitments were drawn from a landscape review encompassing both peer-reviewed literature and federal guidance available at the time of publication (Adams et al., 2024). Similarly, there is an ongoing need for alignment of the myriad sets of principles, guidelines, and frameworks for responsible health AI currently proposed by various national organizations. The Code Principles and Commitments are

not intended to be a “one-size-fits-all” vision or goals statement that should be adopted wholesale by other groups, but rather as a reference point to promote national alignment. Wholesale adoption of the Code Principles and Commitments without identifying organizational values and goals would not bring about the same level of commitment, given that people support what they help create (Christiano and Neimand, 2018). During the process of cross-walking with the AICC, in addition to furthering national alignment, organizations and individuals could contribute to the continual improvement of the AICC if they identify gaps or opportunities for revision of the current Code Principles and Code Commitments.

Alignment Among Federal and State Governmental Agencies

An additional need for alignment exists in the context of state and federal legislation and regulation. A patchwork of disparate regulations within the United States can create a costly, complicated compliance environment and present a risk of impeding innovation, in part because small, innovative companies may struggle to track and comply with regulations across all states and territories, and some companies may avoid bringing innovations to states with burdensome regulations. But small innovators and idea incubators contribute significantly to the innovation of new technologies (Kesavan and Dy, 2020). Additionally, fragmented regulations may lead to uneven consumer protections across various jurisdictions as seen with “health settings outside the hospital and clinic” (Aggarwal et al., 2020).

Alignment of federal and state regulations to ensure consistency in AI governance across different jurisdictions could be facilitated by establishing task forces or working groups composed of federal and state legislators and regulators to address AI policy and regulatory issues. These groups could work to ensure ongoing communication, joint decision making, the development of unified or aligned strategies, policies, and regulation, and collaborative learning. They could also develop shared metrics for evaluating the impact and effectiveness of AI regulations, allowing for consistent assessment and improvement (IOM, 2002).

National Standards for Responsible Health AI

Multiple public and private entities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) have drafted or produced guidance on AI development and testing (FDA, 2022; ISO, 2023). However, there is currently no governing body responsible

for the codification of health AI evaluation standards, resulting in inconsistent evaluations of AI solutions (Saria, 2022). Convergence on shared standards is foundational to consistently optimized outcomes.

A fundamental need is for objective and verified assessment of conformity to standards around processes and outputs, including reports on long-term model performance across various populations and sites. There is an opportunity to learn from the electronic health record (EHR) certification processes established by the ONC. Lessons include the need to (a) test and certify products in settings and on data comparable to real-world applications; (b) address misaligned incentives for certification bodies paid by developers; (c) provide public evidence in support of adherence to standards rather than to rely solely on attestation; (d) recertify periodically; and (e) conduct post-market surveillance to promote maintenance of certification and local governance (Ratwani et al., 2024). There is currently “no publicly available, nationwide approach that enables objective assessment of health AI models and the consequences of their use” (Shah et al., 2024, p. 245). Verifiable, objective, and ongoing standards-driven assessment of health AI models and systems is critical to ensure that the risks of AI in health care and biomedical research are identified and proactively mitigated and to engender trust among all key stakeholders. Such an assessment should be supplemented by the need for an infrastructure for local validation and implementation science framing to ensure effective use of AI.

National Standards for Education About AI

An essential component of establishing shared goals and expectations about health AI is establishing a baseline, a common understanding about what exactly AI is, how it works, what benefits it presents and risks it poses, as well as what accountabilities various parties have in its use. While AI is playing an increasingly important role in health care delivery, AI is typically identified as a gap in medical education (Krive et al., 2023). Establishing admission requirements, core medical education curriculum and/or continuing medical education, and board certification requirements could reduce the knowledge gap in the field (Paranjape et al., 2019). Similarly, guidance around health AI in nursing and allied health training and practice is limited (Glauberman et al., 2023). Collaboration among educational accrediting bodies to establish curriculum standards for medical education and health care professional education in general warrants further consideration.

LOOSE: IMPLEMENT AND INNOVATE

Local Implementation and Governance

Local implementation of health AI applies the vision, values, goals, and expectations set out in the Tight 1 phase with consideration for the local organizational culture and requirements as well as sub-population patient preferences. It is an exercise in change management and addresses issues including leadership support, alignment with organizational vision and priorities, communication strategies to ensure understanding and ongoing alignment, and establishing goal posts to measure success (Phillips and Klein, 2023).

Broadly, governance is a “systemic, patterned way in which decisions are made and implemented” (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2016), and local governance typically refers to the applications of policies, procedures, and oversight mechanisms by non-governmental organizations. It includes alignment and compliance with federal, state, and local regulations and contractual requirements, and alignment with national consensus organizations. It provides for ethical oversight and ensures appropriate processes and metrics for testing and monitoring of new and existing systems (Kim et al., 2023). Local governance also defines skill requirements and training expectations for teams using health AI and establishes authorities and accountabilities for the use of health AI in the local context.

An example of local adaption of AI applications would be for a rural hospital that cares for a large migrant farm-worker community to include workflow elements intended to reflect data collection, patient communication and language preferences, and re-contact needs. The goal would be to achieve pan-stakeholder agreement on health outcomes. Another example is an urban setting in which transportation, access, and health care delivery trust are primary care barriers, and an emphasis on adapting AI applications to focus on patient needs and preferences in these settings aimed at promoting human health is warranted.

There has been considerable focus on the development of frameworks and maturity models to measure the capability of health care delivery systems to deploy, use, and monitor AI solutions frameworks, including national coordinating groups such as the Health AI Partnership (HAIP, n.d.) and the Coalition for Health AI (CHAI, n.d.), as well as commercial entities such as MITRE (2024), and large clinical systems such as Duke AI Health (n.d.). However, there has been limited reflection on the whole of health AI governance, and there are currently no national standards against which organizations can measure their performance on all aspects of local health AI governance. While

some of these standards could be addressed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services (CMS) safety requirements for health systems (Fleisher and Economou-Zavlanos, 2024), there remain safety challenges for health AI that are likely to require AI-specific safety controls. As these controls mature, they could be incorporated into expectations set by accrediting bodies such as The Joint Commission or the National Committee for Quality Assurance. Within the context of health AI, components warranting consideration for maturity models include presence and adherence to organizational policies and procedures, a program for monitoring outcomes, clear accountability structures, and training and communication plans.

Technical Implementation Support for Under-Resourced Health Care Organizations

When considering the establishment of sound health AI governance and the adoption of health AI, local context is important. For under-resourced organizations such as those that are small, that function in rural settings, or that serve populations at risk, the ability to attend to the complexities of health AI is limited when those organizations are compared to larger and better-resourced entities. This could lead to such systems not adopting health AI or being unable to properly control the management of health AI adoption and use; either case could result in an expansion of disparities and/or the digital divide. A similar risk was identified during the adoption and use of standardized health information technology (IT) such as EHRs by health care organizations. As noted earlier in this chapter, to address this risk, Congress used the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act to direct HHS to establish the Health IT Regional Extension Center (REC) Program (ASTP ONC, n.d.). The $720 billion REC program was aimed primarily at helping providers who were treating underserved populations, promoting dissemination of information and assistance on best practices for health IT adoption and ongoing use. The types of local entities receiving REC funds to train providers included health IT research and consulting organizations, universities, quality improvement organizations, and health center networks (Lynch et al., 2014).

Most providers who received assistance from RECs had adopted EHRs, and nearly half had met the criteria for “meaningful use” for obtaining the HITECH federal incentive dollars (Farrar et al., 2015). A similar program with funding to support development and dissemination of best practices for health AI could help entities (under-resourced entities in particular) to develop and implement strategies for deploying responsible AI.

Promotion of Innovation

Novel AI tools offer a transformational opportunity to improve human health and to create meaningful value for all key stakeholders. Flexibility in the Loose phase is required to foster innovation supported by a culture of creativity, collaboration, and measured risk-taking, as well as rigorous assessment, all conducted within the parameters set forth in the Tight 1 phase. Advances can be derived from efforts and investment by public agencies, private organizations, or public–private partnerships.

In the context of public efforts and investment, federal agencies engaged in the support and conduct of research can provide guidance on the needs, gaps, and priority areas in health AI research and fund special initiatives and consortia for critically needed research that may not be feasible in a small setting. For example, HHS’s Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) is seeking to develop calls for research proposals and funding to develop democratized real-world health care data sources from EHRs, claims data, social determinants of health, and environmental data, among others. They are also seeking to provide mechanisms to use these data for AI training through federated mechanisms that facilitate wider and more equitable AI tool development (ARPA-H, 2024). Another example of this is the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning Consortium to Advance Health Equity and Researcher Diversity (AIM-AHEAD, n.d.) whose focus is to advance health equity and develop capacity for AI experts among underserved populations. At a more foundational level, the National Science Foundation (NSF) has been funding a wide range of AI research projects through many initiatives, including the National Artificial Intelligence Research Institutes (NSF, n.d.). Some of the innovations from these initiatives have diffused into the health space and are driving some of the innovation in this sector. Ongoing funding for robust scholarly study is essential to build the needed evidence base to advance AI for human health.

Big tech has poured hundreds of billions of dollars into AI research and development (Ahmed et al., 2023b). However, as noted earlier, while small innovators and idea incubators generate important solutions and new technologies (Kesavan and Dy, 2020), they are often unable to compete at scale, and as a result, their advances may not be realized or may be delayed in the market. It may be beneficial to consider developing governmental programs that support entrepreneurs, start-ups, and small businesses, particularly minority-owned, as an alternative to those that require such commitments as an equity stake in the company or a share of future revenues.

Public–private partnerships offer another means of promoting innovation in health AI. Of particular interest is the role of government agencies partnering

with private organizations (such as academic institutions and/or technology companies) “to facilitate the translation of health data into actionable insights to streamline operations, improve care coordination, and enable greater insights” (Arnaout et al., 2023). Public–private partnerships can yield innovation that would otherwise be impossible, impractical, excessively time consumptive, or cost-prohibitive for any individual academic group, private organization, or government agency, and as such, provide an important path forward to advancing health through AI.

Regulatory Innovation

Rapidly evolving technologies can present challenges for regulatory bodies, both in assessing whether and how existing laws, rules, and frameworks apply to the new technology and in responding thoughtfully and rapidly to identified gaps. In this Loose phase of change at scale, innovation in policy making through regulatory sandboxes presents an opportunity to mitigate the risks associated with unintended consequences of maintaining current policy by granting individual exceptions to existing regulations, allowing policy makers to monitor the differences in outcomes that current rules yield relative to the exception (Leckenby et al., 2021). The results of these exceptions then inform legislative or regulatory changes based on “more robust regulatory knowledge” (Buocz et al., 2023). Although they have been used in regulation of financial technology, regulatory sandboxes also present an important opportunity in areas such as health AI to inform policy making, to reduce time to market for new products, and to promote greater safety for consumers (OECD, 2023).

Another innovative regulatory approach has been proposed by Blumenthal and Patel (2024) who posit that the novel challenges of generative AI (GAI) require special consideration for governance. Given a general-purpose technology that is subject to model drift, and which may produce unreliable results, they suggest “one possible direction would be to treat these GAI-based clinical applications not as devices but as a new type of clinical intelligence” (Blumental and Patel, 2024). This novel approach would require managing these GAI-based tools much the way a clinician is treated, through proper training, testing, supervision, ongoing retraining, periodic reporting on quality to regulatory authorities, and so forth.

Financing AI in Health Care Delivery Systems

While the integration of AI into health care delivery systems holds much promise, it is also fraught with financial challenges that raise significant

concerns. Testing various means of paying for health AI is consistent with the local application of new technology in the Loose phase. The high initial costs of acquiring AI tools, the ongoing expenses related to maintenance and updates, and the need for specialized personnel to manage these systems represent substantial financial burdens. Moreover, the disparities in financial resources among various stakeholders can exacerbate existing inequalities, leading to unequal access to cutting-edge AI innovations. Foregoing some type of financial support for AI may not be desirable. Like telemedicine, without adequate reimbursement for AI in its early stages, longer-term benefits of AI for health outcomes and operational efficiency may not be realized (Parikh and Helmchen, 2022). The pressure to demonstrate return on investment is significant; AI has been used by providers and payors to improve their financial position. Providers have used AI to maximize revenue by optimizing coding, improving billing accuracy and completeness, and streamlining the prior authorization processes (Zhu et al., 2024). Simultaneously, much attention has been given to using AI to detect fraud in medical billing (du Preez et al., 2025). Payors have used AI to automate claims adjudication, resulting in more and more-rapid denials, leading to iterative and escalating responses between providers and payers (Williams, 2024). The application of the Code Commitments to Advance Humanity and Ensure Equity by all parties will be necessary to ethically address competing priorities during this Loose phase.

Some AI tools may offer benefits that are not immediately reflected in a health system’s bottom line, making the investments more challenging to justify from a purely financial perspective. For example, AI tools can analyze a patient chart and identify pertinent information for a clinician, potentially significantly reducing provider time for record review, and thereby potentially improving clinician well-being (Parikh and Helmchen, 2022). These financial hurdles necessitate an exploration of potential funding models, cost-benefit analyses, and strategies for ensuring equitable access to these tools by health systems. Ensuring that the advantages of AI in health care delivery are accessible to all, regardless of financial standing, is crucial for fostering innovation and assuring equitable distribution of the benefits.

Costs Associated with Implementing AI in Care Delivery

Estimates of the costs of investment by health sector stakeholders in implementation of AI, for either in-house solutions or purchased systems, are opaque and dependent on the specific applications deployed. For example, the total cost of deployment of a chatbot might be several thousand dollars per year, while the total cost, including integration of a complex predictive model into an existing system could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars over time (Sanyal,

2021). Many cost estimates consider only the up-front costs. A comprehensive understanding of the total cost of AI systems is important and includes not only up-front costs, but also integration with existing systems, ongoing data management and security, system monitoring and maintenance, staff acquisition and training, and regulatory compliance.

Financial Benefits Associated with Implementing AI in Care Delivery

A major driver of the use of AI in the sector is clearly improved health. Beyond improved clinical outcomes, economists have predicted significant financial benefits from the use of health AI, including one estimate of a 5–10% reduction in annual health care spending (Sahini et al., 2023). Anticipated efficiencies yielding cost reduction opportunities abound. Using AI, health systems may improve efficiency in patient–provider matching, scheduling, referrals, and reduction of missed appointments. AI-powered clinical decision support systems can speed health care professionals’ workflows by providing real-time recommendations based on evidence-based guidelines (Sutton et al., 2020).

Beyond self-funded AI implementation, several innovative approaches are being tested or could be tested in this Loose phase to support equitable access to the benefits of health AI. CMS is currently approaching AI reimbursement in three ways: (1) simply including AI as part of existing payments for services, (2) providing an additional transitional payment, or (3) creating a new procedure and paying for it independently of other services (Zink et al., 2024). CMS could incorporate AI costs into existing bundled payments for services while modifying the price of the bundled reimbursement based on quality of the AI and costs for its development, balancing innovation and affordability for clinicians (Zink et al., 2024). AI device manufacturers could consider offering volume-based pricing and accept downside risk if patient outcomes are not realized; or, gain-sharing models could be established between device manufacturers and clinical systems (Parikh and Helmchen, 2022). Expansion of effective approaches and/or the development of novel reimbursement strategies should be pursued, ensuring that they balance innovation and uptake with responsible, value-based use in practice.

TIGHT 2: MONITOR AND REPORT OUTCOMES

Evaluation Metrics

During this phase of scaling health AI, the objective is to assess the performance of health AI in the local context, considering adherence to stated processes and

requirements, as well as performance relative to intended outcome goals identified in the Tight 1 phase. As stated earlier, reproducible, measurable, transparent, and standardized, interpretable metrics are needed.

Health AI applications cover a broad range of technologies, from traditional predictive models to more evolutionary GAI. Each such domain requires tailored evaluation methods, yet the absence of standardized metrics leads to fragmented and difficult-to-compare assessments. This diversity complicates direct comparisons and undermines the consistency of performance claims. While it may not be possible to specify the exact metric applicable to a specific use case and no single standardized metric can be used to assess performance of all health AI applications (Hicks et al., 2022), there are a number of frameworks by which metrics can be deemed sufficient and the processes used to establish and evaluate health AI, and the downstream actions, surveillance, and eventual decommissioning standardized.

FDA (2021) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA, 2021) provide some relevant guidelines for AI evaluation; however, these are not universally applicable or consistently used across different types of AI systems. In 2023, ISO issued an international standard for the management of AI technologies in practice with the intention of addressing challenges in ethics, transparency, and continuous learning; it specifically includes sections on performance evaluation and improvement (ISO, 2023). However, this standard is high level and is intended to be a starting framework to grow as AI maturity grows.

The Joint Commission’s Responsible Use of Health Data certification program assesses controls for secondary uses of health care data (including AI training or local validation) in areas of de-identification, data controls, limitations of use, and transparency to patients, as well as the process an organization has put into place for validation of any data-based algorithm.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has published guidance on standards for evaluation of health AI for medical devices (WHO, 2021); this guidance is relevant to health AI more generally and local implementation specifically. It includes consideration of discriminating measures capable of identifying patients who will, versus those who will not, have an adverse event, as well as calibrating measures capable of assessing the accuracy of risk prediction (Alba et al., 2017). The WHO model also calls for evaluation of AI performance on sub-populations as appropriate as well as for comparison outcomes relative to care delivered without AI. Furthermore, the model calls for careful consideration of issues such as sample size, inclusion criteria, and follow-up periods, and at a minimum recommends measurement of clinical processes and outcomes, potential harms, user and recipient experience, and comparisons to gold standard.

Robust local evaluation of implemented AI systems is essential to ensuring that health goals are achieved, and trust is built and maintained. Collaborative development, broad stakeholder engagement, and standards alignment between and among organizations and agencies seeking to govern or accredit local health AI users warrants careful consideration. Specific issues that must be addressed include those that follow.

Reliability and Validity

Shared, standardized performance metrics are essential for ensuring the reliability and validity of health AI systems. These metrics ideally encompass various dimensions of performance, including accuracy, generalizability, interpretability, and fairness (Kiseleva et al., 2022; McCradden et al., 2023). By standardizing such measures, stakeholders can more accurately gauge and understand the effectiveness of AI applications, leading to more informed and empiric decision making when selecting, designing, optimizing, and monitoring AI platforms.

Accuracy and Generalizability

Accuracy, a critical performance metric, determines the correctness of AI predictions or classifications. Generalizability, on the other hand, assesses the system’s ability to maintain performance under varying conditions (Daneshjou et al., 2021; Fehr et al., 2024). Standardizing these metrics would allow for consistent benchmarking, enabling stakeholders to identify the most reliable systems.

Interpretability and Fairness

Interpretability refers to the ease with which stakeholders can understand and trust AI decisions. Fairness ensures that AI applications do not perpetuate or exacerbate biases in underlying data or as encoded in algorithms (Fehr et al., 2024; Vollmer et al., 2020). Again, establishing shared metrics for these dimensions of health AI is crucial for enhancing trust and ensuring ethical AI deployment in various clinical settings.

AI Model Performance Transparency

As is the case for AI evaluation metrics, transparency standards are essential to demonstrating efficacy and building trust, and such standards currently do not exist, from the perspective of either researchers or end users or the recipients of AI. With an agreed-upon set of standard performance metrics, dissemination of results will be important for various audiences. An initial set of requirements for algorithm transparency came from ASTP ONC in the form of transparency requirements for algorithms incorporated into certified health IT (ONC, 2024a).

Additionally, reporting frameworks for AI-focused clinical studies have been adopted by major peer-reviewed publications in biomedical and life sciences. Such reporting standards emphasize transparency, reproducibility, and clarity in the documentation of AI methodologies and results. Key frameworks, such as Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials for AI and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials–Artificial Intelligence (SPIRIT-AI), provide guidelines for reporting clinical trials involving AI, focusing on detailed descriptions of the AI intervention, data pre-processing, model training, and validation processes (Ibrahim et al., 2021). These standards also stress the importance of disclosing performance metrics, such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and any potential biases. Furthermore, they require authors to describe the clinical context, intended use, and limitations of the AI system, ensuring that peer reviewers and readers can critically assess the validity and applicability of the research findings.

In the context of a clinician assessing an individual algorithm, model cards or labels may provide a template for ensuring transparency (Sendak et al., 2020). The proposed model labels aim to provide frontline clinicians with an easy-to-digest, one-page document with the necessary information to help end users to know when and how to apply AI model output in decision making. In addition to statistical performance of the AI model, facts include essential information such as an overview of the model, outcomes and outputs, data sources, uses and directions, and warnings.

From the perspective of patients and their advocates, transparency is essential to ensure clinical benefits and mitigate risk of harms (The Light Collective, 2024). The group is calling for transparency about why and how their data are being used in AI models; when AI is guiding their care; and what the level of evidence is to support the use of AI in their care.

Capacity for Shared Learning Between and Among All Stakeholders

A feedback loop from the Tight 2 local context (bottom up) to the Tight 1 broader governance context (top down) stages of change at scale is essential to ensure ongoing learning and adaption across the whole of the health ecosystem. There are a variety of capacity-building approaches to consider. Interdisciplinary coalitions, collaboratives, and networks may hold joint meetings, workshops, or conferences to exchange insights, recognize shared obstacles, and create joint solutions.

Collaborative research projects involving health care providers, patients, AI developers, and academic institutions offer an opportunity to explore AI

applications and their implications in clinical settings. Funding specifically in support of multidisciplinary collaboration could promote diverse perspectives in AI health care research.

Shared learning could also be advanced through online learning platforms with e-learning modules tailored for different stakeholder groups, including clinicians, developers, and patients and through communities of practice where stakeholders could share experiences, best practices, and resources related to AI in health care.

Additional opportunities include pilot projects with planned and structured debriefing sessions to capture learnings and insights and simulation-based training to allow stakeholders to experience AI-driven health care scenarios. Knowledge brokers could bridge the gap between AI developers and health care practitioners, translating technical AI knowledge into practical insights for clinical use. And finally, it is essential that researchers and AI practitioners regularly publish their findings from AI health care initiatives in accessible formats, such as white papers, case studies, and reports, to inform and educate stakeholders.

Key components for successful implementation of safe, effective, trustworthy health AI can be considered from a Tight-Loose-Tight framework, summarized in Table 6-1, where broad, shared agenda setting is followed by local implementation and innovation, and then monitoring and reporting of outcomes for shared learning. In the Tight 1 phase alignment on vision, values, goals, and expectations can be advanced through state, federal, international, and public–private collaboration on shared standards and assurance. Innovation and implementation in the Loose phase can be supported through local governance, public and private investment, and regulatory experimentation. Finally, standardized evaluation metrics, transparency, and ongoing feedback and shared learning are needed to ensure success in the Tight 2 phase to promote change at scale. Critical collaboration and work remain for all stakeholders across all phases of change to ensure that the benefits of health AI are realized.

TABLE 6-1 | Summary of Key Components to Advance Health AI via the Tight-Loose-Tight Framework

| Key Components to Advance Health AI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tight 1 | Loose | Tight 2 | |

| Goal | Align vision, goals, and expectations | Innovation and implementation | Promote change at scale |

| Actions | State, federal, international, and public–private collaboration on shared standards and assurance |

|

|

| Stakeholders |

|

|

|

| Priorities |

|

|

|