An Artificial Intelligence Code of Conduct for Health and Medicine: Essential Guidance for Aligned Action (2025)

Chapter: Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In the past decade, significant advances in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have created transformational opportunities for health, health care, and biomedical science, offering new tools to improve effectiveness and efficiency in a myriad of applications in the health field. Advancing AI capabilities are arriving contemporaneously to new and exacerbated challenges in health care, including staff burnout and shortages, an aging population with growing disease burden, increasing costs of care, and persistent issues with equity in access and outcomes. Despite sustained attention, conventional strategies have not yielded the desired improvements in population health, cost containment, patients’ experience, clinician well-being, or equitable outcomes. The need for new approaches to address these long-standing challenges is evident; AI offers both new hope and new concerns.

AI is being used and championed to drive transformative progress in diagnostics, population health, care quality, patient safety, clinician experience, and clinical and administrative efficiency. AI risk prediction tools, such as cardiovascular risk calculators, have been in use for decades. AI use in radiology is widespread (Yordanova, 2024); AI tools are showing promise in improving speed and accuracy of pathology results (Greeley et al., 2024; McGenity et al., 2024); and AI tools are being used to automate clinical documentation and other routine tasks (Abdelhady and Davis, 2023). AI is increasingly being used and evaluated in clinical decision support applications to support more tailored and targeted recommendations. And generative AI interactive chatbots are being employed in a variety of health and health care settings (Kurniawan et al., 2024).

However, certain concerns about AI have also been raised. Much attention has been given to risks of exacerbation of existing system biases as well as introduction of new forms of bias (Obermeyer et al., 2019; Topol, 2019). An important issue related to equity is scope of access to the benefits of AI and the need to ensure availability to transformative tools in to both high- and low-resource health care settings. Additional concerns include data security and individual privacy; accuracy

and reliability of results; explainability, transparency, and accountability; and influences on humans, whether through impacts of automation on the workforce or through influences of AI anthropomorphism on individuals and patients. Other challenges are related to user preferences and workflow integration, which are present in any health technology, but have distinct manifestations in health AI.

The integration of AI into health, health care, and biomedical science applications requires realization of AI’s transformative potential. The ethical deployment of AI necessitates proactive harm-reduction strategies to ensure that its positive effects are maximized while minimizing negative externalities. To this end, many entities, from the organizational to the global level, have developed AI governance frameworks to address these concerns.

The objective of the AI Code of Conduct (AICC) project is to harmonize the existing principles, address identified gaps, and map these principles to the National Academy of Medicine’s Learning Health System (LHS) Shared Commitments (McGinnis et al., 2024). From this set of aligned principles, a small number of simple rules were developed based on complex adaptive systems theory which posits that individuals adhering to a concise set of agreed-upon simple rules can create change at the system level (Adams et al., 2024). The AICC framework is deliberately designed as a touchstone for organizations and groups developing their own approaches and considerations to consider for inclusion and alignment when assessing internal guidance for completeness in their specific context, thereby advancing trust and minimizing the likelihood of actors across the field working at cross-purposes. This set of simple rules is presented as Code Commitments. Described in detail in Table ES-1, they are intended to serve as guideposts for all stakeholders as they develop and use AI.

Commitment 1: Advance Humanity

- Development of standards and other governance structures to assess alignment by developers and users of health AI with societal and cultural goals for health AI

- Incentives and structures for independent evaluation, certification to the AI Code Commitments, and public and transparent reporting on certification status

Commitment 2: Ensure Equity

- Standardized metrics to assess and report bias in data, AI output, and AI use, in the interest of equitable distribution of benefit and risk

- Incentives and supports to low-resourced organizations and communities to ensure equitable access to the benefits of AI

Commitment 3: Engage Impacted Individuals

- Participation by all key stakeholders across the health AI lifecycle

- Local governance bodies that include all stakeholders in the AI lifecycle cross-purposes

- Common understanding and education of all affected parties

Commitment 4: Improve Workforce Well-Being

- Positive work and learning environments and culture (NAM, 2022c)

- Measurement, assessment, strategies, and research (NAM, 2022c)

- Reskilling and training programs for workforce AI competency

- Disruptive technologies with change management strategies that promote

- worker well-being

Commitment 5: Monitor Performance

- Standardized quality and safety metrics to be used to assess the impact of the use of health AI on health outcomes

- Aligned frameworks for safety, equity, and quality in AI performance

Commitment 6: Innovate and Learn

- A well-supported national health AI research agenda

- Participation in shared learning across all stakeholders

- Innovation as a core investment

Key stakeholders—including developers, researchers, health systems and payors, patients, ethics and equity experts, quality experts, and former leaders of federal agencies—considered the role of their respective groups in applying the Code Commitments. Chapter 5 of this publication details their work efforts. Within the main report, a table is provided that describes commonalities in stakeholder actions, and Table ES-1 describes elements in which one stakeholder group has distinguishing or leading roles and responsibilities. This includes important considerations such as ensuring broad stakeholder participation throughout the AI lifecycle, assessing AI tools initially and continuously for technical and health outcomes, promoting transparency, promoting continuous learning, identifying and addressing conflicts of interest and objectives, considering and addressing bias, implementing incentives to encourage desired behavior, promoting user-centered design, promoting local governance, and creating and supporting a culture of safety.

To achieve trustworthy health AI at scale, the development, implementation, and use and monitoring of and ongoing learning about health AI will require intentional and sustained collaboration between and among all impacted

| Stakeholder | Distinct Contribution |

|---|---|

| Developers | Developers have vast experience in methods and practices, and their active participation in developing standards for the industry will be foundational. |

| Researchers | Researchers are positioned to provide scientifically sound and independent assessment of both methods and outcomes associated with health AI, including issues of data de-identification and sharing and the associated implications of societal benefits and burdens, as well as the best practices and standards in workflow integration. |

| Health Systems and Payors | Local adaptation that facilitates human agency and promotes patient-centered care is the purview of health systems and payors, as is the training and support of the health care workforce in the use of AI in the local health care delivery context. They have an opportunity to create financial incentives that support equitable and effective health AI, using both increases and decreases in reimbursement to support desired best practices around AI use. |

| Patients and Advocates | Patients, as the recipients of health AI, are uniquely positioned to describe in detail their experience about the impacts of health AI on their lives. Only they can articulate their preferences about critical issues such as access controls over their data or explanations about when and how AI is used in their care. Only patients can share their own personal experiences, both positive and negative, of engagement with developers and the health care system as the use of AI for diagnosis, treatment, and payment advances. And patients are by definition the only source of patient-reported outcomes. |

| Federal Agencies | The funding and regulatory authority held by the federal agencies has the power to shape the future of health AI. Some examples of how these tools could take form include through support for studies to measure how AI can influence patient health, human agency, goals of care, and human–human interactions in the presence of AI interventions; through recognition of standards for collection and exchange of relevant data and encouraging use of the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement for making data available for training algorithms, and prioritized research projects; or through the expansion of requirements in AI product labeling based on real-world performance. |

| Health Care Workforce | As end-users of some types of health AI, the health care workforce is situated to identify workflow needs and priorities, and as purchasers or influencers of purchasing decisions, clinicians in particular may have contracting opportunities to require disclosure of AI models’ alignment with the Code principles and commitments and to address liability concerns should model outputs cause harm. |

| Quality and Patient Safety Experts | Quality and patient safety experts and accrediting organizations play the role of an independent auditor, ensuring that processes are designed and implemented and that metrics are developed and routinely assessed to ensure the quality of outputs and reduce the risk of harm from health AI tools. |

| Ethicists and Equity Experts | Ethics and equity experts are uniquely qualified to consider and weigh the novel tensions that health AI presents across various stakeholder priorities, always holding the greatest good for the health of the individual and the community as the north star. They are positioned to serve as guides on the path to implementing trustworthy AI. |

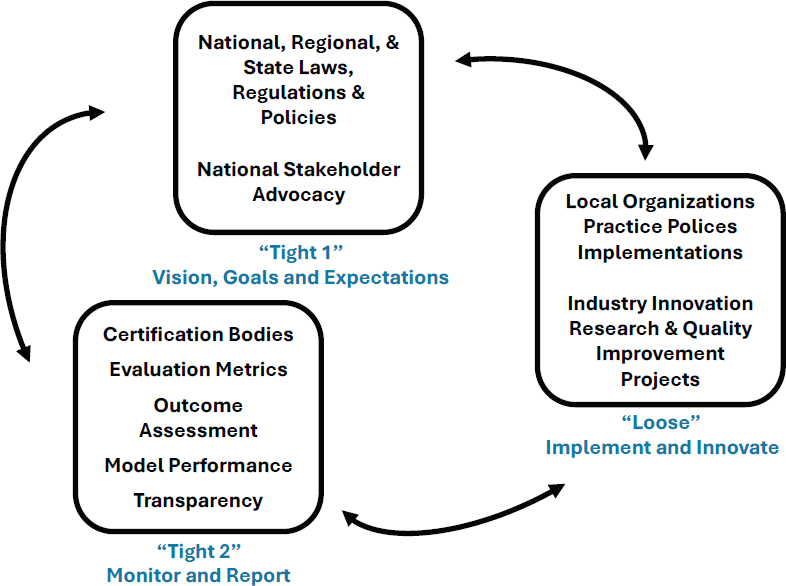

stakeholders. Herein, the Tight-Loose-Tight leadership model (see Figure ES-1) is applied as a construct to scale change in complex systems. It is designed to balance innovation and control through an iterative, dynamic approach that encourages collaboration and builds trust. During the first Tight phase, the goal is to align stakeholders on vision and expectations; an example is alignment on governance frameworks. During the Loose phase, local implementation leads to learning and innovation. Finally, the second Tight phase promotes change at scale through evaluation metrics, and standards, among others. Key components to advance health AI through the Tight-Loose-Tight framework are presented in Table ES-2.

Finally, a small number of strategic priorities were identified by the authors as most likely to support the achievement of each Code Commitment. These key priorities with associated actions and responsible actors are described in Table ES-2 by Code Commitment.

With intentional, sustained effort and ongoing communication, feedback, and collaboration by all stakeholders, safe, effective, and efficient advancement of responsible health AI is possible. Realizing the benefits and mitigating the

SOURCE: Conceptually adapted from Compton-Phillips, 2019.

TABLE ES-2 | Summary Priority Actions to Operationalize the AICC Code Commitments

| Commitment | Action | Involved Parties |

|---|---|---|

| Advance Humanity |

|

|

| Ensure Equity |

|

|

| Engage Impacted Individuals |

|

|

| Improve Workforce Well-Being |

|

|

| Commitment | Action | Involved Parties |

|---|---|---|

| Monitor Performance |

|

|

| Innovate and Learn |

|

|

NOTE: ASTP ONC = Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

risks will require significant engagement, which will be more likely to come to fruition if it is easy and rewarding to abide by the shared vision, values, goals, and expectations described in the nationally aligned AI Code Principles and Code Commitments.

This page intentionally left blank.