An Artificial Intelligence Code of Conduct for Health and Medicine: Essential Guidance for Aligned Action (2025)

Chapter: 2 Background

2

BACKGROUND

DEFINING ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

The term “artificial intelligence” (AI) was first introduced by John McCarthy at the seminal 1956 Dartmouth Conference, where the vision of making “machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves” was articulated (McCarthy et al., 1955). Overall, AI refers to a subdiscipline of computer science and a constellation of technologies that perform tasks that have traditionally required human intelligence. Core AI research areas include methods for learning, reasoning, problem-solving, planning, language and speech understanding, and visual perception.

Howell and colleagues (2024) suggest three “epochs of AI.” In the first epoch, early AI was focused on symbolic and probabilistic reasoning (e.g., expert systems applied to decision pathways, Bayesian models used for clinical decision support). In medicine in the late 1950s, AI efforts centered on providing support for diagnosis and decision making, based on a foundation of probability and utility (Ledley and Lusted, 1959). In the second epoch, endeavors explored the use of logic-based inference (Buchanan and Shortliffe, 1984). Research in the 1980s sparked a statistical revolution in AI founded on principles of probability and utility that provide a frame for today’s efforts and methods (Horvitz et al., 1988); this included advances in AI-powered medical diagnosis with rich representations known as Bayesian networks and related representations of probability and utility (Heckerman et al., 1992; Pearl, 1988).

In the last 20 years, AI has transitioned from a niche scientific pursuit to a foundational set of technologies poised to have impact in multiple domains, including health, health care, and biomedical science (NAM, 2022a). In the early 2010s, deep learning methods emerged and allowed programs to dramatically

improve data-driven classification and prediction tasks (e.g., identification of diabetic retinopathy in retinal images (Gulshan et al., 2016). In the third and most recent “epoch of AI,” foundational models and generative AI (including Large Language Models [LLMs]) have further extended deep learning methods, changing the paradigm from task-specific tools to tools that “can do many different things without being retrained” (Howell et al., 2024) (e.g., chatbots that can interact with patients for varied purposes). Taken together, recent advances in data availability, computing power, and computational methods have resulted in rapidly accelerating innovation (Horvitz and Mitchell, 2024). As noted above, advances in AI in recent years in data-driven machine learning (ML) techniques were foundational for these advances. ML-powered advances have been particularly impactful in the areas of language and vision. The advances with ML were also deeply dependent on the voluminous increases in data made available as a result of the massive digitalization of processes and communications as well as the pooling of such data made possible with broad interconnectivity, along with the dramatic decrease in storage costs. Additionally, ongoing specialization in computer chips (e.g., from central processing units, designed for general-purpose, sequential processing, to graphic processing units capable of high-speed parallel processing) have enabled the more intense computational demands of advanced ML procedures (Dean, 2022).

Several forms of data-driven ML have been employed in medicine. These include supervised, unsupervised, reinforcement learning, self-supervised learning, and newer techniques using deep neural networks. Figure 2-1 provides an overview of the categories and basic characteristics of both knowledge- and rule-based systems (noted above) and data-driven ML.

Supervised learning relies on labeled datasets, where the input data (e.g., findings and symptoms presented by a patient) are paired with the desired output (e.g., diagnoses). This approach has been used to train ML models to predict medical outcomes based on evidence presented to the AI systems. Supervised ML has been the basis for advances in performing medical diagnosis and predicting outcomes (Bayati et al., 2014; Wiens and Shenoy, 2018) and image analysis. Supervised ML has also been used to perform diagnoses from radiological and photographic imagery (e.g., skin, pathological sections, blood smears).

Unsupervised learning involves analyzing data without pre-defined labels. The goal is to find hidden patterns or intrinsic structures within the data. A common technique would be clustering. This type of learning is particularly useful for exploratory data analysis, such as grouping similar patients together based on presentation patterns (Alizadeh et al., 2000).

Self-supervised learning is a subset of unsupervised learning that generates its own labels from the data. It typically involves tasks such as predicting missing parts of

the data. For example, a model might learn to predict the next word in a sentence or the next frame in a video sequence based on the context provided by previous words or frames. This method is a foundational training mechanism behind recent advances in natural language analysis and vision-based AI systems as it enables the training of models using vast amounts of unlabeled data.

Reinforcement learning is a method in which the purpose is for an agent to learn the optimal action path toward a stated goal or “reward” using experience in an environment rather than labeled datasets. Generally, these algorithms optimize for a long-term reward maximization based on the Markov decision process that recommends actions at discrete time steps based on this framework. This type of learning is particularly useful for recommendations based on user interactions and optimization challenges (Komorowski et al., 2018). An example of this would be to help decide on optimal treatment pathway recommendations in complex cancer treatments and surgical approaches, to maximize the probability of an outcome that should be prioritized, such as quality of life or lifespan (Khezeli et al., 2023).

On another dimension, ML can be defined by target uses and goals of the system. The uses can be broadly divided into discriminative and generative models, each with distinct objectives and application categories. Discriminative models classify items based on input features, such as medical diagnoses, laboratory tests, and wearables’ data, mapping inputs to outcomes of interest. Generative models, on the other hand, learn from the patterns and relationships in training datasets, enabling the creation of new data instances that resemble training data. Generative models power AI applications in language generation, image creation, and scientific simulations.

Discriminative ML is highly promising for high-stakes medical decision support, as the methods are founded in well-characterized approaches to learning and reasoning under uncertainty. A few examples of this type of AI have been used in clinical practice widely as early examples were adapted to be calculated and used manually by clinicians (Bayati et al., 2014; Gomes et al., 2022; Mumtaz et al., 2023; Rajaguru et al., 2022; Xing et al., 2018).

Deep neural network (DNN) models—the development for which the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable ML with artificial neural networks” (Nobel Prize Outreach AB, 2024)—are based on the automated construction of multilayered computational neural networks (often compared to the structures in the brain in their layered connectivity) that have propelled AI capabilities forward. This approach used in models, such as DeepFold (Pearce et al., 2022) and AlphaGo (Kemmerling et al., 2024), may hold promise if applied to various challenges in health research and care delivery. AI is currently experiencing an inflection point, driven by DNNs over

the last decade. Great amounts of data and advances in computer power coupled with core algorithmic innovations (e.g., back-propagation and convolution), and developments with larger computing architectures (e.g., Transformers) have contributed to AI success in tasks such as speech recognition and image analysis. Significant progress has been made possible by DNNs, including reducing word error rates in speech recognition and achieving expert-level performance in medical image interpretation. There has been much excitement about the power of neural-network-based generative AI systems to produce language and imagery and to perform problem-solving. Applications of the technology are wide-ranging and include creating art, writing code, designing products, and helping with scientific hypothesis generation and research.

ML tools and technologies, including discriminative ML and foundational models and generative AI, offer distinctive benefits in health and health care applications. For example, the algorithm-driven technologies have demonstrated power and robustness for high-stakes diagnostic reasoning and therapy planning, and the generative AI technologies are showing early signs of potential for assisting with diagnostic and therapeutic reasoning and perhaps with even more prowess with natural language, illustrated by their strength in supporting tasks such as summarization of notes and report generation. It is particularly important to note that, notwithstanding the excitement about the most recent technologies, algorithm-driven ML continues to demonstrate its value with its complementary powers and applications in medicine and is also at an early stage of adoption.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE USE OF AI IN HEALTH, HEALTH CARE, AND BIOMEDICAL SCIENCE

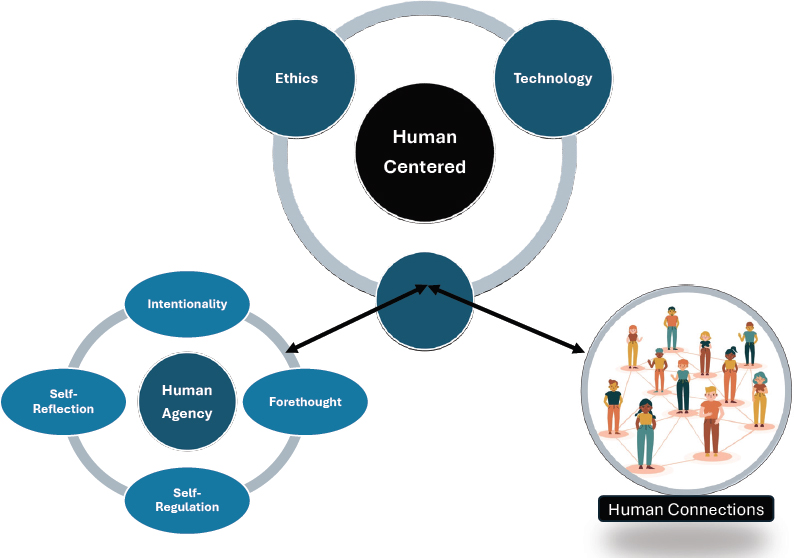

The use of AI technologies that mimic or exceed human capacities is expected to be transformational in health care, along with almost every other sector of society. AI is being or may be used to support medical research, design new therapies, diagnose illness, identify personalized treatment plans, write patient care summaries, translate clinical advice for patient education, submit claims, appeal insurance denials, among a myriad of possibilities. Amid these advances of AI technologies and their applications in health, health care, and biomedical science, the criticality of human primacy, agency, and connection must be paramount. See Figure 2-2.

First, until there is adequate evidence that AI is equivalent or superior to human decision making within the context of each use case, and this performance can be safely and equitably sustained, AI systems may best be designed to support human decision making, as assisted by AI rather than ceded to it. Applying

SOURCE: Bandura, 2006.

Human Factors Engineering principles and the concept of the copilot in aviation, AI developers can design systems that are subject to human oversight and communicate effectively with the human in the loop, yet still have assigned autonomous functions and clearly complementary skills and serve as a backup for human decision making (Sellen and Horvitz, 2024). Note, however, that humans can experience reliance bias from AI recommendations, and careful assessment of performance and feedback loops regarding AI-assisted human decision making in the context of use, and additional research into how to most effectively support human cognition with AI, is warranted (Jabbour et al., 2023).

Second, agency—defined here as the ability of individuals to make informed choices and take actions based on personal goals and values—is embedded in the LHS Shared Commitment, “Health and health care that is ENGAGED” (McGinnis et al., 2024) and is essential for AI systems developers to recognize and incorporate. Issues of personal control include both employing personal data in AI models as well as controlling recommendations or decisions made by AI systems (Li et al., 2022). Effective decision making is dependent on the

understandability of AI-generated recommendations or decisions, including issues of risks, benefits, accuracy, reliability, and robustness of the underlying models, as well as the provision of well-calibrated uncertainties about inferences and recommendations to both patients and providers (Nori et al., 2023). Another important direction is the explanation of inferences and recommendations to physicians and patients, with appropriate references to information from the patient, the electronic health record, and the relevant literature (Sellen and Horvitz, 2024).

Finally, the maintenance of human connection is foundational to health (HHS, 2023b) and to trust in the healing relationship. Patients have a critical need for human connection when it comes to their health and important medical decisions, and physicians derive professional satisfaction and meaning in work based on these relationships (Hiefner et al., 2022). Under ideal practice conditions, clinicians have a broader contextual understanding of patients and their care goals than any automated tool. In addition, clinicians are ultimately accountable for health-related recommendations and therapies rendered to patients. Ideally, great AI enhances the human connection by both automating tasks and supporting human cognition through algorithms and naturalistic interfaces, ensuring that the human connection is more informed, meaningful, and decisive. Thus, when developing and deploying AI in health care settings, maintenance of “human connection” must be prioritized amid a world of rising automation.

HOW ADVANCED AI IS DIFFERENT THAN RULE-BASED DIGITAL HEALTH TECHNOLOGIES

Underlying technological differences in data processing, algorithmic characteristics, programming techniques, and computational resources have resulted in distinct differences in the capabilities of AI systems using ML or foundational models/generative AI (FM/GAI) systems (advanced AI) as compared to knowledge and rule-based (KRB) digital health technologies. ML-based AI is being developed and deployed in a rapidly evolving environment, with a new array of available tools, creating new opportunities and risks (Topol, 2019); and in the context of necessary attention to management of data and models, development and deployment, algorithms and infrastructure, ML-based AI has potential to scale in ways unimaginable with rule-based systems (Carnegie Mellon University Software Engineering Institute, 2021).

At a basic level, static, rule-based engines execute commands on structured data inputs, which are often limited in complexity, while discriminative ML and

FM/GAI systems rely on probabilistic statistical models and pattern recognition to predict designated outcomes using very large, growing, and changing datasets, which can include both structured data and unstructured natural language, images, audio, sensor, and video data. While all these systems may be run in extremely powerful, distributed cloud-computing environments, KRB digital health systems are less likely to be designed to take advantage of advanced computing power and distributed, disparate, and more complex data resources.

Unlike digital health technologies which require a human being to modify the rule-based engine, discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems may learn from available data, changing over time, without human intervention, creating challenges with explainability and transparency (Band et al., 2023) and requiring ongoing monitoring (Feng et al., 2022). Generative AI can create new information based on predictions gleaned from data, both historical and real-time and sometimes producing inaccurate results or hallucinations (Howell et al., 2024). Additionally, some AI systems have the capacity to interact with users, delivering human-like responses (Fernandes and Goldim, 2024), while others, like the AI systems behind self-driving cars, are capable of autonomous decision making (Bitterman et al., 2020). A side-by-side comparison of these differences in and implications of AI system features is outlined in Table 2-1.

These distinctive capabilities of various types of AI systems have resulted in a major shift in scale and scope of available systems, with a large and growing set of new tools being used to solve a wide variety of potentially novel challenges for a broad audience in the health arena, including clinicians, patients, researchers, developers, administrators, device manufacturers, and policy makers (AHA, 2019). The speed of new development and uptake of these tools has been rapid; in a recent survey commissioned by Microsoft, more than three-quarters of health care organizations reported using AI technologies (IDC, 2023). Open AI’s chatbot, ChatGPT, had more than 180 million users with more than 1.6 billion visits per month as of February 2024 (Mortensen, 2024) many of whom may be turning to ChatGPT over traditional search engines for medical advice (Sandmann et al., 2024), thus making available the power of AI to a large majority of providers and patients in the United States.

Additionally, though not a systems feature, governance structures currently represent a point of divergence between rule-based digital health systems and payor AI systems. Rule-based systems are more mature and more limited in scope and have been carefully considered for inclusion and updating of existing governance frameworks, at the local, state, and national levels. AI governance structures can borrow from established risk management and health information technology governance frameworks, but some of the distinctive challenges in

TABLE 2-1 | Comparative Features and Implications of Various Categories of AI

| System Feature | Knowledge and Rule-Based Systems | Discriminative Machine Learning | Foundational Models and Generative AI | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Tasks | Static predefined tasks based on predefined logic | Delivers predefined tasks based on training dataset(s). Requires retraining for new tasks or application to new data | Capable of novel tasks based on extremely large training dataset. Retraining not required | Discriminative ML and FM/GAI offer opportunities to solve much more complex tasks. |

| Type of Data Employed | Typically, use structured or coded data and are often limited in complexity and number of sources of data As complexity and number of data features are more limited, data quality and characteristics (missingness, etc.) are easier to assess |

Can employ structured and unstructured data, including text, images, genomic, audio, video, and multimodal sources. Can access data across multiple platforms Large numbers of data features create challenges in assessing data quality, missingness, variability, and availability across the full set of source data |

Discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems may increase risk of exposure of personal health data, including protected health information. All technology types may introduce bias based on data characteristics or on how the features included in the logic or model are selected. Discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems are much more susceptible to these effects. |

|

| System Feature | Knowledge and Rule-Based Systems | Discriminative Machine Learning | Foundational Models and Generative AI | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Processing, System Learning, and Adaptation | Operate based on static, predefined rules and protocols. These systems do not adapt or improve unless manually updated and they are incapable of learning Generally curated to prioritize administratively or clinically meaningful features, which can limit performance but also improves interpretability and may limit overfitting to the local data context Challenge to keep these systems current and to harmonize content across rules |

Employ data-driven, adaptable computational models to learn from vast datasets, including patient records, imaging data, video, audio, and genomic information, allowing AI to continuously update its predictive outputs | Discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems are based on complex data and adaptable over time. Some methods do not have explainable underlying logic (black box), and transparency and interpretability can be challenges. Because discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems and data change over time, resulting accuracy may change (and degrade) over time (model drift). KRB technologies are unable to learn and adapt to accumulating data. |

|

| System Feature | Knowledge and Rule-Based Systems | Discriminative Machine Learning | Foundational Models and Generative AI | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern Recognition | Require human interpretation and coding of pre-defined patterns Rely on clinically or administratively meaningful data features that are human encoded and likely to be causal or associated with the purpose of the technology, improving interpretability but limiting performance |

Excel at identifying patterns in complex medical data, such as detecting anomalies in medical images, predicting disease outbreaks, or recognizing trends in patient symptoms | Discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems can be capable of making connections that are not readily transparent to end users, potentially leading to earlier and more accurate inference and application. However, these inferences may be subject to overfitting and lose accuracy outside of the population in which they were developed. KRB technologies may miss informative data features that are non-intuitive to human developers. |

|

| Prediction | Wide use of historical risk calculators and rule-based tools Can introduce bias and experience performance changes over time as data and clinical practice change |

Can predict patient outcomes based on comprehensive data analysis | Discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems may improve outcomes by forecasting disease progression, personalizing treatment plans, and identifying patients at high risk for complications. Different challenges arise for classification versus accurate individual risk prediction. |

|

| Can present challenges with portability and adaptation to the local context as AI overfits to the source data context and requires evaluation, monitoring, and local adaptation | Has an improved capacity to include context in predictions | |||

| System Feature | Knowledge and Rule-Based Systems | Discriminative Machine Learning | Foundational Models and Generative AI | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability and Robustness of Results | Consistently produce the same results with consistent inputs Unexpected inputs may result in clear error messaging as the inputs can be scored and tracked |

Provides consistent results from consistent inputs | May yield inconsistent and inaccurate results (hallucinations) with consistent inputs | Discriminative ML and FM/GAI may produce inaccurate results that are difficult to discern from accurate results. |

| Present significant challenges in determining etiology of change when the AI algorithm is a black box, and multiple source features are changing over time | ||||

| Automation of Complex Tasks | Capable of automation of straightforward tasks, including scheduling appointments, generating billing, and basic data entry, but lack the sophistication to handle more complex administrative and clinical tasks | Can automate complex tasks, including interpreting such things as radiology images and pathology samples, processing natural language in EHRs, and personalizing patient care plans | Discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems are better suited to model tasks as they become more complex. All types are susceptible to changes in the sequence and character of complex task processes and require maintenance and surveillance for intended function. | |

| Interactivity and Human-like Capabilities | Offer static user interfaces without the ability to understand natural language or engage in interactive, human-like communication | Produces relatively static output formats and fixed integration into user workflows. Fixed inputs although the development of the inputs can be done in a fully automated and data-generated fashion | Can provide context-aware interaction with end users. May power interactive technologies such as data visualization or synthesis as well as virtual health assistants and chatbots, which can understand and respond to end-user queries | FM/GAI systems may be anthropomorphized, which may be a benefit or a harm, depending on the use case and the level of user sophistication. Increasing end-user flexibility of interaction may come with unintended outcomes, both benefits and harms. |

| System Feature | Knowledge and Rule-Based Systems | Discriminative Machine Learning | Foundational Models and Generative AI | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scalability and Flexibility | Require significant modifications to adapt to new applications or scale with increased data. They are often less flexible and more challenging to customize |

With the appropriate guardrails, may be scalable across clinical settings and can be tailored to specific clinical needs and patient populations (Pouyan, 2024) Lower barriers to customization |

Discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems have shown that general-purpose systems can be developed at scale. However, overfitting to the development data environment and limitations in transportability of models require adaptation and customization for a local context of use (Lasko et al., 2024). For specific use cases, highly tailored KRB technologies may still have superior accuracy or reliability when compared to discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems. |

|

| Real-time Processing and Insights | Can provide real-time data processing with lower computing costs due to simplicity of rule-based systems | Provides real-time data processing and actionable insights, can integrate dynamic, changing data elements and variable processing intervals over time Requires attention to scalable architecture to manage computing costs |

All types of systems present challenges in ensuring that the data stream has sufficient fidelity and quality for the context of use due to real-time use. | |

| System Feature | Knowledge and Rule-Based Systems | Discriminative Machine Learning | Foundational Models and Generative AI | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testing and Ongoing Monitoring | Assessed based on the system’s functional conformance to specifications; identified errors and new features typically addressed in batch mode | Assessed based on statistical (quantitative) and qualitative model quality relative to requested task and desired outcomes | Assessment of outputs may be more complex due to changes to output over time Assessment relative to desired outcomes is essential |

All systems require ongoing monitoring, but discriminative ML and FM/GAI systems have more complex requirements to ensure safe, equitable performance. Ensemble AI automation (e.g., use of one model to monitor another model) can be applied to support monitoring and performance maintenance of complex AI systems. AI and economic performance measures. |

NOTE: EHR = electronic health record; FM/GAI = foundational models/generative AI; KRB = knowledge and rule-based; ML = machine learning.

these technologies have yet to result in mature AI-adapted governance structures. In addition, while access to large AI systems may be limited to organizations with significant resources, creating potential equity issues, access to AI systems has been democratized because of the availability on cell phones and via the Internet, making adherence to best practices more difficult to detect and address in some settings (e.g., physicians using LLM tools to summarize notes or to appeal insurance denials).

RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH THE USE OF AI

Novel attributes and rapidly changing capabilities of AI systems relative to rule-based digital health technology yield both impressive opportunities for new functionality along with both overlapping and risks (FDA, 2021, 2022). As briefly outlined in Table 2-1, there are considerations applicable to rule-based, discriminative ML, and FM/GAI-based systems which include data privacy and security; introduction of a variety of forms of bias from the process of tool development; the intended function and the context of use; reliability of results;

and impacts of automation on human experience and the workforce. Other considerations are more specific to discriminative ML, and FM/GAI-based systems, such as explainability and transparency; anticipated and unexpected bias from the training source data; anthropomorphizing technology, including deep fakes; model drift and the need for ongoing monitoring; and real-time processing and scalability. All these challenges have the potential to create snowball-like impacts for any of the issues noted here and negatively impact equitable access.

Data Privacy and Security

Massive amounts of data are essential for advancing AI in health and health care (Mandl et al., 2024) as they enable the development of sophisticated models capable of delivering personalized treatments, predicting patient outcomes, developing new therapies, and improving efficiency. However, the aggregation, management, and licensing of these extensive datasets introduce significant privacy and cybersecurity risks. Safeguarding patient data requires robust encryption, strict access controls, and adherence to regulatory standards to prevent unauthorized access and data breaches. Poorly understood, broad consents for use of personal data that consumers have granted to big tech firms in exchange for “free services” (e.g., chatbots, smart watches, and so forth) also present risks to individual privacy, yet remain unregulated. The licensing and sharing of health data by health delivery systems must balance the benefits of data-driven innovation with the ethical obligation to protect patient confidentiality and agency. For example, collecting deeply personal information—voice, eye movement, facial expressions, body movement, and reaction times—and employing these data in behavioral health applications hold promise to significantly improve access to treatment as well as quality of care, but also presents substantial risks for harm if these data are accessed and used nefariously (Olawade et al., 2024).

Bias

AI systems reflect the structural biases embedded in the data on which they are trained as well as the conscious and unconscious biases of developers and end users of AI. If the training data are biased or unrepresentative of the target population, including the predicted outcome of interest, AI systems can perpetuate and even exacerbate existing health disparities (Obermeyer et al., 2019); and the models may perform poorly on groups under-represented in the data. For example, facial recognition technologies developed on non-diverse

populations perform poorly on non-White populations (Grother et al., 2019). If used in diagnostic algorithms (Qiang et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2021) without eliminating the bias, it could lead to misdiagnoses and inappropriate treatments in health care applications. For example, lack of representative training data in pulse oximeters led to lower accuracy among patients with darker skin (Sjoding et al., 2020) and subsequently to delayed recognition of hypoxia during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fawzy et al., 2022). In health care, this can result in distorting model output, including recommendations or decisions, impacting patient care and outcomes.

Explainability and Transparency

As opposed to rule-based tools which were explicitly designed with explainability and interpretability in mind, many ML-based models, particularly those using DNNs, by nature behave as “black boxes,” making it difficult, even for their developers, to understand how they arrive at specific determinations (Saeed and Omlin, 2023). It should be noted that there are opportunities to combine more “black box” methods with either explainable discriminative ML or rule-based systems, and this is an area of ongoing research. However, in some contexts of use, this lack of explainability can hinder transparency (sharing with impacted parties information about data sources, methodologies, and testing results) and thus negatively impact trust and acceptance among health care professionals and patients. Moreover, while naturalistic interfaces in generative AI tools may support chain-of-thought reasoning, the identification and correction of errors may still prove challenging.

Reliability of Results

Given the potential for AI dependence on training datasets with particular attributes, some AI systems may falter when data not conforming to the training dataset attributes are presented (Finlayson et al., 2021), yielding inaccurate results, a concept known as overfitting on the training data attributes. This is particularly problematic for health care diagnostic and treatment recommendations, where outcomes have potentially life-altering impacts. This challenge is exacerbated by the issues of explainability and transparency noted above (Saeed and Omlin, 2023). New AI techniques are being employed to reduce these risks, including the use of more robust validation datasets as well as application of generative models, federated learning, and synthetic datasets (Hong et al., 2023).

Impacts of Automation on Health Care Decision Making, Human Experience, and the Workforce

AI systems capable of autonomous decision making pose the risk of over-reliance on technology for clinical decision making, loss of human connection (Quinn et al., 2021) and significant changes for the health workforce, including retraining needs and job loss (Reddy, n.d.). Among AI-assisted tools that provide recommendations or cognitive support, there is also a risk of users depending excessively on AI recommendations or visualizations, resulting in bias and over-reliance (Jabbour et al., 2023), as well as the potential for de-skilling (Aquino et al., 2023). And, while in some situations, interaction with AI chatbots could improve equity of access (Habicht et al., 2024), it is possible that when engaging with chatbots rather than humans, patients may feel isolated and their trust in the healing relationship could be eroded.

As AI systems become increasingly adept at performing tasks such as diagnostics, treatment planning, and administrative workflows, the traditional roles and skill requirements within the health care workforce are set to undergo profound changes (Davenport and Kalakota, 2019). Initially, AI is poised to ameliorate the workload of documentation, theoretically allowing clinicians to more fully engage with their patients (Tierney et al., 2024). Furthermore, the integration of AI could lead to important shifts in workforce composition. Various members of the health care workforce, supported by advanced AI tools, might take on responsibilities traditionally held by doctors, thereby altering the professional landscape. While AI may offer solutions for workforce shortages and enhance efficiency of operations, job displacement concerns as well as issues associated with electronic health record (EHR) use may dampen the appetite for AI adoption among physicians. There is also a need for training in use of AI, continuous education, and retraining. Clearly, workforce and educational implications are significant and are addressed in a later section in this publication.

Anthropomorphizing Technology

Anthropomorphism ascribes human qualities—those not seen in traditional systems including moral character, status, and judgment quality—to AI systems that do not in fact possess them (Placani, 2024). Yet, some AI outputs are presented with human-like characteristics such as emotion, physical appearance, and even self-consciousness (Steerling et al., 2023) and can be offered up in a conversational manner that mimics human communication, potentially leading to emotional response or overconfidence in outputs by the end users. While limited research

has been done in this arena (Liu and Tao, 2022), over-reliance or declining trust are both potential downstream risks that must be considered. In addition, increasingly granular data collection from facial expressions, voice patterns, and other human behavior, could be used to create AI outputs that are virtually indistinguishable from reality, so-called “deep fakes,” that can be used to impersonate an individual and could result in serious personal harm (Mirsky and Lee, 2021). Navigating these challenges is critical to harnessing the full potential of AI in health care while maintaining public trust and ensuring patient safety.

Data and Model Drift and Ongoing Monitoring

AI models that continuously learn, adapt, and encounter new data over time can improve their performance but must be properly monitored. Poor performance can result in suboptimal care, misappropriation of resources, and safety risks (Davis et al., 2017). Changes in data patterns or the emergence of new medical knowledge can render existing models outdated, not helpful, or even harmful (Kore et al., 2024). Conversely, online AI or ML that learns continuously from incoming data presents a different risk of drift in which the performance of the tool and outputs could shift in response to the data but not the underlying design or health goal. In all cases, implementing robust monitoring and updating mechanisms are essential to ensure that AI systems remain accurate and effective (Davis et al., 2022).

Real-Time Processing and Scalability

Given the real-time processing capacity of AI within clinical systems (e.g., colonoscopies and surgery) (Topol, 2019), any issues with the model (e.g., drift) may not be detected before clinical decisions are made, potentially leading to patient harm. Scalability presents an escalation of risks mentioned above, including data privacy, bias, model reliability, and model drift. Scaling AI also involves increased resource utilization. The use of AI in health care requires substantial energy consumption and affects the carbon footprint associated with training and operating advanced ML models (Jia et al., 2023). As health care (and other aspects of society) become more dependent on AI, the potential for increasing the impact of AI on the climate cannot be ignored. Data centers housing AI systems require vast amounts of electricity for computation and cooling, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. This results in a careful tradeoff of building new AI resources versus retraining or adapting existing resources given the computational and environmental impact of large model development.

Equitable Access

Substantial organizational resources are required to develop, acquire, implement, and govern health AI responsibly. Beyond the cost of development or procurement, needs for technical, analytic, and compliance expertise are typically expensive and can be out of reach for small, rural, or poorly resourced health organizations. One study demonstrated that AI was more likely to be incorporated into medical care in higher-income, metropolitan areas (by zip code) with academic medical centers (Wu et al., 2023). As a result, there is a risk of inequitable access to potentially life-extending AI tools for patients seeking care at lower-resourced organizations, further exacerbating existing inequities in care.

New and Emerging Tools, Including Large Language Models

“The foundation model (FM) is a family of machine artificial intelligence (AI) models that are generally trained by self-supervised learning using a large volume of unannotated dataset and can be adapted to various downstream tasks” (Jung, 2023). Foundational LLMs are distinguished by using a set of AI technologies and developing meta-parameters and internal representations entirely from a set of source data. Foundational LLMs can be adapted through few-shot learning (an ML technique that trains AI models to make predictions using a small number of labeled examples) and reinforcement learning for specific use cases. LLMs present new classes of risks not previously encountered in software as medical devices (FDA, 2021, 2022) and relying on them for high-risk health care functions will require special testing, monitoring, and oversight. Foundational LLMs can hallucinate by providing inconsistent results or omissions, and the quality of their responses can fluctuate over time (Perković et al., 2024).

The largest foundation language models also present risks for introducing or perpetuating bias. They have been trained on vast datasets, many from the public Internet, that reflect societal discourse replete with cultural, political, and scientific biases (Zack et al., 2024). Additionally, LLM development can employ an alignment approach called reinforcement learning with human feedback that involves human trainers providing feedback on the model’s outputs. Human trainers may unconsciously introduce biases during this process or be instructed in a manner that ultimately shapes model responses.

Yet, for consumers and patients, not since Google Search (Tang and Ng, 2006) has there been a widely available information technology innovation as impactful for health as LLM-based chatbots. They may fill in key gaps in consumer access to expert health advice. However, they introduce risks that warrant careful

consideration. Privacy and data security are paramount concerns, as chatbots often collect, store, and use sensitive personal information, perhaps in a manner not apparent to the user. Miscommunication and errors can arise from their limited understanding of context and nuance, potentially leading to misinformation or inappropriate responses. Additionally, consumer and patient reliance on chatbots for critical tasks could reduce important medical oversight. Ensuring ethical use, robust security measures, and continuous improvement in their accuracy and fairness is essential to mitigate these risks.

Regulation

Keeping pace with innovation poses a significant challenge for regulators; technologies, such as generative AI tools like ChatGPT, which produce unvalidated outputs, provide a clear example of a tool that may have unpredictable impacts on health care systems (Bouderhem, 2024).

Balancing innovation with transparency of the AI inputs, outputs, and expected operation as well as transparency of disclosure of AI use, equity, and safety needs are daunting, and much work is being done by AI researchers to address the data and technical challenges; simultaneously, governance efforts—local, national, and international, and including this AI Code of Conduct (AICC) framework—are being developed to address the risks to ensure that the benefits are realized evenly across society (HHS, 2024a; Hong et al., 2023; Quinn et al., 2021).

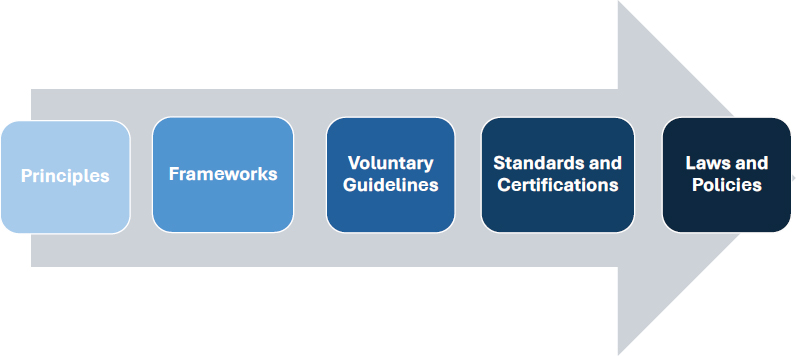

ALIGNING AI GOVERNANCE EFFORTS FROM THE ORGANIZATION TO THE GLOBAL ARENA

AI governance has been defined as “a system of rules, practices, processes, and technological tools that are employed to ensure an organization’s use of AI technologies aligns with the organization’s strategies, objectives, and values; fulfills legal requirements; and meets principles of ethical AI followed by the organization” (Mäntymäki et al., 2022). Governance can be employed at an organizational, local, national, international, or global level. The continuum of the forms of governance, from most conceptual to most enforceable and based on the work of Mills and colleagues (2023), is outlined in Figure 2-3.

Given the potentially transformative benefits of AI to improve health, health care, and biomedical science, along with the risks of AI outlined above, a central goal of the National Academy of Medicine AICC project is the alignment on a set of foundational principles and commitments designed to promote responsible use of AI across the health sector in the United States. There is a broad recognition and

SOURCE: Conceptually adapted from Mills et al., 2023.

clarity among the authors that while ethical principles and commitments provide a governance starting point, organizations that develop and/or deploy AI in the health sector will also require more detailed guidance enabled through broader accountability frameworks, standards, and policies. Additionally, AI systems and their accompanying opportunities and threats are not bounded by local, state, or national borders. Therefore, these alignment efforts across the governance continuum must also be viewed from a global perspective.

Several factors are driving and influencing global governance of AI. AI development involves transnational actors, particularly multinational corporations (Kshetri, 2024), for whom common rules could ease regulatory burden (Tallberg et al., 2023). AI has the potential to provide significant economic advantages, leading to competition in the international race for AI dominance, potentially stifling cooperation (Vijayakumar, 2023). AI systems create externalities that transcend national borders, necessitating international cooperation for effective regulation to create a level playing field in the interest of all parties (Tallberg et al., 2023). In addition, AI is financed, developed, used, and governed by a diverse set of international actors with varying resources and sometimes disparate or competing values, incentives, and motivations, creating a complex governance landscape (Gianni et al., 2022).

While there are growing efforts to promote international collaboration, AI governance efforts to date have been largely nationally focused. For example, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office for Civil Rights (OCR) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services issued a final rule

under the nondiscrimination section of the Affordable Care Act (HHS, 2024a), specifying that patient-care decision support tools, including ML and AI models, must not exhibit “discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability” (HHS, 2024a). Discriminatory practices are prohibited and will be enforced under existing federal laws, including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Department of Justice, n.d.). However, the specific policies and procedures needed to comply with the statute still require substantial development. Further complicating the ecosystem in the United States, state-level regulations are being enacted or considered. Across 48 states and Puerto Rico, a broad range of bills to address the risks of AI were introduced in 2025, and resolutions were adopted or bills passed in 26 states (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2025).

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) AI Policy Observatory recorded more than 700 national AI governance initiatives from 60 countries and territories (Tallberg et al., 2023). Despite having developed national AI strategies, many countries are now struggling to establish more robust governance, which require careful consideration of issues including risk-based frameworks, licensing agreements, liability structures, standards, and research and development support (World Economic Forum, 2024).

AI presents some challenges and special considerations for governance.

- Uncertainty: The performance of novel applications of AI techniques and tools is difficult to predict, including the intended and unintended outcomes of such applications. This presents challenges in proactive governing and confidently assessing the best approach to governance. Considerations include the types of governance models that are most appropriate, which aspects of AI should be included or excluded in governance, and at what level governance should occur—regional, national, or international level (Sepasspour, 2023).

- Rapid evolution: Breakthroughs in AI development have and are expected to continue to outpace the capacity of traditional governance approaches, which typically lag new technologies. This is in part because of the lengthy legislative process and in part due to the inability of regulators to assess rapidly the benefits and risks associated with the technology (World Economic Forum, 2023). Adaptation and collaboration with the private sector will be required to respond to this environment (Best et al., 2024).

- Societal impact: Given the apparent “general-purpose” nature of AI (Crafts, 2021), the scope of impact on society is quite broad and will be felt across most industries and sectors. The historical approach to technological innovation is one primarily focused on profit, which can result in societal

- harm; consideration for alignment of AI investment with the public interests—“economic, societal, and national security objectives”—is warranted (Mazzucato et al., 2022).

- Competition: Significant private investment in AI development (Ahmed et al., 2023b) can create fierce competition for market advantage, and result in a focus on speed over safety or profit over ethics (Dafoe, 2018). Additionally, such competition can create “winner-take-all” or “winner-take-most” scenarios, concentrating benefits, both economic and political, in a small number of organizations or countries (Muro and Liu, 2021).

- Fragmented governance: Various non-governmental parities are engaged in the creation and use of AI technologies and tools, and many are actively working on AI standards and governance frameworks. Broad collaboration and inclusive participation of parties with international influence and/or their deep technical expertise will be essential in the ongoing development of AI (Schmitt, 2022).

- Geopolitical competition: Competition is not limited to commercial interests; international competition is focused on geopolitical wealth and power advantages (Dafoe, 2018). In such a high-stakes environment, where national security is deemed a risk, cooperation to establish AI governance standards and regulatory frameworks can prove challenging, particularly among nations that are not ideologically aligned, as is seen in the oppositional positioning on AI between the United States and China (Roberts et al., 2024).

- Lack of consensus on priorities: Key stakeholders do not agree about which challenges associated with AI should be prioritized or about the policies that would address the issues. For example, the United Kingdom is focusing on existential harms, while the European Union is emphasizing near-term risks such as bias (Roberts et al., 2024).

In response to these challenges, a growing number of public and private international organizations have engaged in governance efforts from convening experts to developing international regulation to fill the gaps. As documented in the draft AICC literature review, there is significant synergy around the underlying principles of responsible AI (Adams et al., 2024). However, numerous approaches to governance are emerging. For example, at the G20 summit in New Delhi in September 2023, a human-centric AI governance framework was proposed by the Indian Prime Minister, and an AI risk monitoring body based on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was suggested by the president of the European Commission (Kshetri, 2024). Table 2-2 provides a sampling of key international AI governance efforts across the continuum since 2019,

TABLE 2-2 | A Sampling of Key International AI Governance Efforts Since 2019

| Form of Governance | Year | Sponsor | Description | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principles | 2019 | European Commission | High-Level Expert Group on AI presented Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence | https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai |

| 2019, Updated 2024 | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) | Adopted by OECD member countries focusing on ethical AI. G20 leaders committed to these principles | https://oecd.ai/en/ai-principles | |

| 2021 | United Nations (UN) Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization | Adopted by all 193 member states to guide legal frameworks for AI ethics | https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/recommendation-ethics-artificial-intelligence | |

| 2021 | World Health Organization (WHO) | Expert report and recommendations for principles to ensure AI works to the public benefit of all countries | https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029200 | |

| 2023 | G7, OECD | Presentation of background and principles for governing generative AI for G7 leaders in Japan | https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/bf3c0c60-en.pdf | |

| 2023 | United Kingdom | Bletchley Declaration, signed by 28 countries during the UK International Summit for AI Safety, emphasizing the need for collective management of AI risks | https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ai-safety-summit-2023-the-bletchley-declaration/the-bletchley-declaration-by-countries-attending-the-ai-safety-summit-1-2-november-2023 | |

| 2023 | United Nations | Interim Report: Governing AI for Humanity | https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_ai_advisory_body_governing_ai_for_humanity_interim_report.pdf | |

| 2024 | WHO | AI guidance on Large Language Models | https://www.who.int/news/item/18-01-2024-who-releases-ai-ethics-and-governance-guidance-for-large-multi-modal-models |

| Framework | 2023 | Council of Europe | Draft framework on AI and human rights, democracy, and rule of law | https://rm.coe.int/cai-2023-28-draft-framework-convention/1680ade043 |

| Regulation | 2024 | European Union | First international regulation on AI | https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AL_202401689 |

| Multilateral Initiatives | 2020 | Global Partnership on AI | Launched by 15 countries to support ethical AI adoption | https://gpai.ai/about |

| 2021 | EU-US Trade and Technology Council | Formed to coordinate activities in AI and other technologies | https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ai-public-good-eu-us-research-alliance-ai-public-good | |

| 2023 | BRICS AI Study Group | Formed to study global equity in AI | https://www.reuters.com/world/chinas-xi-calls-accelerated-brics-expansion-2023-08-23 | |

| 2023 | UN | Formed to support international collaboration on AI governance | https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/231025_press-release-aiab.pdf |

including the work of OECD, the United Kingdom, the European Union (EU), the Council of Europe, the United Nations, and the World Health Organization.

Despite a lack of global consensus on the best approach, there is a clear need and momentum for a governance framework for AI. Taking definitive action, the most stringent international governance of AI is being implemented in Europe via the AI Act, which was passed in March 2024 to ensure that AI development, deployment, and use in the European Union promotes innovation and EU values, while mitigating the risks of AI (Artificial Intelligence Act, EU Regulation 2024/1689). Furthermore, in April 2024, the European Union and the United States agreed on a risk-based approach to AI governance to ensure “safe and trustworthy AI” produced by the United States and the European Union (European Commission, 2024a).

AI governance involves a set of interwoven issues that require coordinated regulation and a nuanced policy agenda. Overarchingly, more international collaboration would be beneficial. This agenda should consider the promotion of innovation to address complex issues and prevent harmful proliferation in the context of a competitive marketplace. Given that the private sector currently controls most aspects of AI, its governance is particularly complex and politically sensitive. AI governance on the global level could be complicated by the dominance of major tech firms or the growing involvement of smaller players, such as emerging technology companies (Kshetri, 2024). In part to promote trust in AI tools and technologies, a variety of stakeholders, including big tech, researchers, and non-governmental organizations, have taken steps to define good governance and use those work products to inform public policy. For example, the Partnership on AI (PAI) was formed in 2016 to develop guidance and inform public policy (Schmitt, 2022), and in 2023, the Frontier Model Forum1 was established to ensure “the safe development and deployment” of cutting-edge AI technologies, known as frontier models. However, the complexity of self-governance by technology companies—particularly in the face of misaligned incentives—was demonstrated by resignation from PAI by Access Now, a digital rights organization, as they “did not find that PAI influenced or changed the attitude of member companies or encouraged them to respond to or consult with civil society on a systematic basis” (Access Now, 2020).

Multiple global bodies and coalitions have begun to formulate an approach to governing AI, with a primary focus on principles and frameworks. While rules and standards for the development and use of AI are being established, keeping pace with AI’s potentially disruptive effects will require major advancement in governance approaches (Sepasspour, 2023). Governing AI effectively will require

___________________

1 See https://www.frontiermodelforum.org/about-us (accessed April 4, 2025).

rapid cycle learning, adaptability, and correction, just as AI has the capacity to rapidly evolve and autonomously self-improve (Bremmer and Suleyman, 2023). The history of Internet governance provides an example, elucidating the potential and the constraints of governance innovation driven by societal and technical advancements while simultaneously emphasizing the critical role of the multistakeholder approach embraced by both national governance bodies and Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (Almeida et al., 2023). Applying these lessons and focusing on alignment will support the advancement of AI governance, locally, nationally, internationally, and ultimately globally.

APPLYING LESSONS FROM EHRs’ ADOPTION TO THAT OF AI

In addition to heeding lessons about governance, careful consideration of the experiences of broad adoption of technology into the health care workflow is warranted. In recent years, AI tools in health care, like EHRs preceding them, have become available commercially and have been met with both hope and skepticism (Cary et al., 2023; Lindsell et al., 2020; Matheny et al., 2020).

Similarly, early discussions about EHRs generated unwarranted claims about benefits (Bates and Gawande, 2003; Hillestad et al., 2005; Lohr, 2005)—consistent with the Gartner Hype Cycle, a widely applied management framework for the consideration of new innovations (Gartner, n.d.). This framework suggests that new innovations follow a replicable pattern whereby an innovation trigger yields inflated expectations followed by disillusionment, improvement, and eventually productivity and broad adoption. EHRs have certainly been the focus of high expectations and disappointments among end users. In this context, comparing EHRs to an unrealistic ideal rather than viewing them as a tool capable of contributing to incremental progress often fueled inflated expectations and subsequent frustration. For example, while a small study of early EHR adopters demonstrated that 81% of clinicians found the EHR to be superior to paper records (Kaelber et al., 2005), the 2021 National Electronic Health Records Survey (NEHRS) estimated that only 25% of physicians were very satisfied and 35% somewhat satisfied with their EHR system (CDC, 2021). Although the journey to an ideal EHR is far from over and similar risks of comparisons to an idealized target exist with the deployment of health AI, considering key lessons that led to broad EHR adoption by U.S. physicians is a valuable exercise as health AI adoption is burgeoning. These lessons are generally organized into two categories: (1) understanding the rationale for adopting health care AI, and (2) translating behavioral intent into practice.

Understanding the Rationale for Adopting Health Care AI

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1985) provides a useful scaffolding for understanding technology adoption and may be a practical construct for scaling health AI use. In the context of EHR adoption, TPB addresses (1) attitudes toward EHRs based on available evidence; (2) establishing an expectation to support adoption (subjective norms); and (3) perceived behavioral control—the belief that a behavior is under the control of the individual—which is influenced by an environment that fosters behavioral control and behavioral intention.

Using Evidence to Impact the National Dialogue

Although early clinical information systems were developed in the 1960s (Atherton, 2011), development and broad adoption was limited for decades. According to data provided by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), in 2008 fewer than 20% of hospitals and physicians had adopted EHRs (ONC, n.d.). The slow EHR adoption trend to that point was due, in part, to the lack of a clear rationale and supporting evidence for adopting an EHR in settings outside large hospitals. A series of Institute of Medicine (IOM, now the National Academy of Medicine [NAM]) reports that focused on health care quality were among the most influential compendia recommending the adoption of EHRs to minimize errors associated with missing data, erroneous data, unavailable clinical guidelines, and siloed patient information (IOM, 1991, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2007). These reports summarized the science around medical errors and poor health care quality. Following these reports, there was a robust conversation in the lay press and the scientific literature to better understand the need for funding (Anderson, 2007) and the potential benefits, pitfalls, and unintended consequences of the use of EHRs (Ash, 2004; Berg, 2001; Han et al., 2005). Importantly, literature from the major hospital systems with internally built EHRs described the efficiency and safety benefits, as well as challenges with the technology, shifting workload, and data security and privacy concerns (Chaudhry et al., 2006). Additionally, the National Research Council published a report in 2009 that identified “persistent problems involving medical errors and ineffective treatment…. Many of these problems are the consequence of poor information technology (IT) capabilities, and most importantly, the lack of cognitive IT support” (NRC, 2009). Federal legislation and regulation followed; the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act (HHS, 2009) provided financial incentives to support the cost of EHR adoption and encourage adoption and meaningful use of EHR technology with penalties for those that failed to do so (Blumenthal and Tavenner, 2010).

With regard to clear rationale and evidence for use of AI in clinical settings, like with EHR adoption, there are similar questions and concerns about the validity of recommendations (Cary et al., 2023; Habib et al., 2021; Obermeyer et al., 2019), potential issues with trust and reliability (Esmaeilzadeh et al., 2021; Liu and Tao, 2022), job displacement (Howard, 2022; Petersson et al., 2022), and ethical infractions (Li et al., 2022; Sartori and Theodorou, 2022). While many experts are touting AI’s benefit for disease prediction (Kumar et al., 2023) and equitable access to health/disease advice (Ayers et al., 2023; Kaur et al., 2024; Kurniawan et al., 2024), the most value in the near term may be in mitigating health care provider burnout (Borna et al., 2024; Levy et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023; Sallam, 2023). Evidence regarding the potential benefits, risks, and costs of partnering with AI in clinical settings is needed. Costs should be described and assessed broadly, and include financial, time, and workflow reduction estimates, to make transparent the degree to which benefits outweigh the risks and costs. This assessment may be an important part of improving attitudes toward using AI in clinical settings, as with EHRs. Many concerns about adopting EHRs were overcome through scientific evidence and communication to various stakeholder groups, it may be advisable to do the same with health care stakeholders to surface and address concerns about AI in health care over time. In addition, evidence generation will create an evidence-based practice of AI in health and health care that may generate reimbursement for its use, which could further accelerate use, and even more importantly, democratization of use in low-resource environments.

Subjective Norms

The health care system is enmeshed in the Era of Entanglement (Johnson et al., 2021), whereby various stakeholder expectations dictate how technology is to function, and health care providers struggle to navigate an ecosystem riddled with regulatory, quality reporting, and social determinants requirements that impact care decisions and delivery. This complex landscape exacerbates the social pressures and expectations health care providers perceive surrounding AI adoption. Colleagues from one setting may de-prioritize concerns about biased data in favor of improved access to tools that minimize burnout, while institutional leadership may discourage using these same tools because of concerns about sharing health information with non-covered entities that may lack strong privacy policies. Although federal incentives were critical to establishing supports and expectations to advance widespread adoption of EHRs across the United States, establishing a culture of acceptance for EHR adoption has been difficult, and challenges with usability and satisfaction persist (Holmgren et al., 2024).

Concerns about the trustworthiness of AI will also need to be overcome. Wherever it has been studied, concerns about reliability, fairness, and bias continue to surface. This is true in lay press as well as academic publications (Angwin, 2023; Sanders, 2024), adding kindling to the combustible notion that AI is not ready for any use at scale, despite some emerging evidence in medical journals suggesting otherwise in specific contexts, such as radiology.

Perceived Behavioral Control

An important lesson from EHR adoption is that many providers have arguably not achieved self-efficacy (confidence in their ability to learn and use EHR systems), resource availability (access to materials that maintain self-efficacy and technological resilience), and a realistic recognition of obstacles, such as technical difficulties, potential disruption to established workflows, and human factors engineering being a work in progress. This perceived lack of behavioral control has contributed to issues such as burnout (Melnick et al., 2020; Moy et al., 2021). These consequences are often attributed to design issues among the vendor community; however, there are data suggesting that health care providers who complete EHR skills training may have improved efficiency, time, and lower rates of burnout versus those who have not completed that training (Lee et al., 2023; Robinson and Kersey, 2018). As AI is implemented in the health care workflow, it will be important to provide necessary resources to improve perceived behavioral control, including education, time to learn and incorporate the technology into the workflow, technical support, and ongoing financial support. Technical support for AI-augmented clinical tools (as currently conceived) will need to consider new failure modes, such as feedback (Aikens et al., 2024) or data biases (Obermeyer et al., 2019; Temple and Rowbottom, 2024).

Translating Behavioral Intent into Practice

Perceived behavioral control is necessary but not sufficient to ensure the widespread adoption of new technologies required for meaningful transformation. While health care providers may feel capable of implementing AI tools, actual adoption requires more than just perceived capability; true transformation demands a multifaceted approach beyond mere availability and perceived ease of use. Based on lessons learned from EHR adoption, successful behavioral change required private and public messaging and assistance investments. As with EHR adoption, successful implementation of health AI may also require regulatory pressure to create technology standards, incentivize national adoption, and even impose penalties for failing to adopt normative approaches to care using AI. Finally,

long-term and sustainable success may benefit from viewing AI in health care as a Learning Health System (LHS) initiative, involving numerous stakeholders, standardized evidence generation, and summative feedback to developers, leading to data-driven innovation and improvement.

Promotion of Use Through Standards, Certification, and Technical Support

Additionally, promoting behavioral control, the HITECH Act established a technical support infrastructure through regional extension centers (RECs). Their mission was to provide state and regional support, including expert knowledge about certified EHRs, adoption strategies for small group practices, and other nuanced help to ease providers into using EHRs in their offices. RECs appear to have added value and some degree of self-efficacy (Furukawa et al., 2015; Green et al., 2015; Lynch et al., 2014; Riddell et al., 2014).

Soon after the passing of the HITECH Act, HHS issued regulations adopting “an initial set of standards, implementation specifications and certification criteria” for EHRs and creating a voluntary certification program (ONC, 2010). These standards and criteria are routinely updated to adapt to changes in standards and policy priorities, including adding requirements for algorithm transparency in the most recent final rule (ONC, 2024a,b). The ONC Health IT Certification Program, which was linked to the meaningful-use EHR incentives programs adopted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, continues today and remains crucial for assuring that EHRs incorporate required standards and functionality (ONC, 2011, 2016). This program manages an authorized testing laboratory and an ONC-authorized certification body responsible for issuing certifications and ongoing surveillance. The evidence for the impact of this program is mixed (Bowes, 2014; Pylypchuk and Johnson, 2022; Ratwani et al., 2024); however, as a result of this program, recent legislation has approved a voluntary EHR certification program for pediatric EHRs, suggesting that at least some communities find it to be of value (Thompson et al., 2022).

HITECH’s Impact

The multipronged approach, designed to advance from behavioral intention to full-scale adoption succeeded in many ways, including increasing EHR adoption (Cohen, 2016; Washington et al., 2017), impacting inpatient mortality rates (Trout et al., 2022), impacting care quality and efficiency (HHS, 2014), and catalyzing new discoveries through programs such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and All of Us that rely on voluminous EHR data. However, the rapid pace of EHR adoption has been associated with nursing and physician burnout (Halamka and Tripathi, 2017; Washington et al., 2017),

leading to initiatives such as Getting Rid of Stupid Stuff (Ashton, 2018), and ClickBusters (McCoy et al., 2022), as well as the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) 25×5 program to decrease the burden of health care provider documentation (Johnson et al., 2021; Moy et al., 2021). These initiatives were enabled by the ongoing evaluation and improvement science focusing on the EHR and will continue into the foreseeable future.

While the HITECH Act defined standards and incentivized adoption, cognitive supports (including user design, workflow integration, and clinical decision support) and interoperability were not adequately considered. Follow-up legislation, the 21st Century Cures Act (2016), included directives to reduce administrative (documentation) burden, improve interoperability, reduce information blocking, and increase patient access to their medical records. Efforts to incorporate user design and provide cognitive support were encouraged but not explicitly called out for regulation.

AI and Translation into Practice

Although the underlying drivers (e.g., incentives, political and economic forces) between EHR and health AI adoption are significantly different, steps to implement AI in health care appear to be following much of the same blueprint discussed above. For example, the Health Data, Technology, and Interoperability (HTI-1): Certification Program Updates, Algorithm Transparency, and Information Sharing (HHS, 2023a) enhances the ONC Health IT Certification Program by introducing pioneering algorithm transparency requirements for certified health IT and enabling clinical users to assess AI and predictive algorithms for fairness, validity, and safety. However, the HTI-1 rule has come under some scrutiny, in part because there are orders of magnitude more AI tools than there are predictive decision support interventions in regulated EHR systems (Sandalow, 2024); additionally, critical questions remain about the needed standards and specifications for reliable local validation and implementation. And challenges with the EHR certification program, such as self-attestation, periodic recertification, and post-market surveillance, are relevant to AI and will require careful consideration (Ratwani et al., 2024). Meanwhile, multiple parties are endeavoring to address risk by establishing certification standards and assurance procedures for currently unregulated health AI (Shah et al., 2024). Establishing the evidence to support such standards presents one of the greatest challenges to moving forward in certification or assurance programs for health AI.

In the context of planned behavioral theory, there is much to learn from the journey taken to make EHR technology commonplace in the United States. Box 2-1 highlights key lessons. As with the EHR, rigorous evidence is needed to support the use of AI to solve myriad problems to foster multidisciplinary

BOX 2-1

Applying Lessons from EHR Adoption to Health AI Implementation

Understand the Rationale for Adopting Health Care AI

- Use evidence to influence the national dialogue

- Change norms and expectations

- Support behavioral self-control

- Increase self-efficacy about use of AI

- Improve understanding about AI among the health care workforce

- Identify and ameliorate barriers to implementation

Translate Intent into Practice

- Promote standards and certification

- Provide technical support and assistive funding

stakeholder understanding of the rationale for the use of AI and to create the necessary subjective norms and standards for its adoption and ongoing use. And, similar to EHR implementation, promoting AI adoption will require training and education to support perceived behavioral control, including technical understanding as well as workflow integration. However, while existing regulations and implementation of EHRs may provide a foundation for adoption of AI, some features of AI implementation, such as issues with model sustainability, will require novel approaches to ensure equity, safety, privacy, and usability over time. Aligning the industry to solve these challenges is the goal of the AICC framework.

LEARNING HEALTH SYSTEM (LHS) CONTEXT

In 2006 the IOM (now the NAM) undertook an initiative to identify necessary actions to expand the evidence base for medical decision making, with the dual objectives of ensuring that necessary care is delivered and unnecessary care not delivered (IOM, 2007). A standing group of senior public and private health organization leaders was established with an IOM Charter that developed the concept and definitional parameters of progress toward a continuously LHS: “one in which science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement, innovation, and equity—with best practices and

discovery seamlessly embedded in the delivery process, individuals and families as active participants in all elements, and new knowledge generated as an integral by-product of the delivery experience” (NAM, n.d.). See Box 2-2.

However, inadequate progress has been made; central issues identified in the IOM report—evidence not being made available at point of care (Nilsen et al., 2024) and evidence not keeping pace with scientific and technological advances—persist and warrant application of complexity science (Braithwaite et al., 2020).

Recent innovations in AI technologies represent a significant opportunity to ameliorate these challenges. AI can support both basic medical science (such as molecule discovery or drug design) and implementation research with processes including literature reviews, study design, participant recruitment, data analysis, and generative modeling, making it possible to reduce the time from study execution to publication. Further closing the gap from publication to clinical practice, though it currently has limitations, AI shows promise in synthesizing systematic reviews (Nilsen et al., 2024) which may support more rapid updates to evidence-based practice guidelines. AI can also integrate new studies with existing research to produce rapid updates to evidence-based guidelines and provide more personalized treatment recommendations at the point of care. With its capacity to handle extremely large, distributed, and diverse datasets in real time, AI holds promise for improving evidence-based practice (EBP) through improved evidence generation, clinical decision support, and patient shared decision making, three essential components of EBP (Nilsen et al., 2024). AI also holds promise to advance the LHS, because at its core the LHS is predicated on the data generated in patient encounters as well as other sources such as wearables and public health surveillance, creating new information and learning to benefit all. See Figure 2-4.

However, AI introduces new risks and may also amplify existing risks. Considerations including data quality, bias, lack of explainability and transparency in some settings, and performance drift over time; these topics will be detailed

BOX 2-2

The Vision of the Learning Health System

Is “one in which science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement, innovation, and equity—with best practices and discovery seamlessly embedded in the delivery process, individuals and families as active participants in all elements, and new knowledge generated as an integral by-product of the delivery experience” (NAM, n.d.).