Frontiers of Engineered Coherent Matter and Systems: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 4 Atoms and Platforms

4

Atoms and Platforms

The workshop’s third session focused on atoms and platforms used for studying coherent matter and systems. The moderator was Fatima Toor of the University of Iowa.

OPTICAL CAVITIES

James Thompson of the University of Colorado Boulder and JILA described various ways that he uses optical cavities to study quantum properties, including entanglement and coherence. Specifically, he said, his laboratory focuses on harnessing light–matter interactions for quantum simulation and sensing.

He began by explaining that researchers in his field use laser cooling to get rid of the entropy of single atoms and get control of their motional degrees of freedom. They can optically pump the internal degrees of freedom and apply coherent rotations on those single atoms and build fantastic quantum sensors. But, he continued, what they would like to do is move to a sort of “collective physics.” That is, they wish to move beyond having independent atoms that are all doing exactly what they want them to do and start to build correlations and entanglement between the atoms and control groups of them.

They do this, he said, by using high-finesse mirrors—that is, mirrors with high reflectivity and low loss—and allowing light to bounce back and forth many times through atoms, and the interaction with that light field builds a sort of connection between the atoms. “We use all of quantum mechanics,” he said, including unitary dynamics, quantum measurement, and dissipation. The goal

is to use these systems to explore the fundamental science of quantum sensing and simulation.

Next, he went into detail on how his group accomplishes this, noting that a number of other groups at other institutions are doing related work. His laboratory is currently running three different types of optical cavities, but each uses laser cooling to slow down atoms and trap them between mirrors. One system uses rubidium atoms, and two use strontium atoms. This arrangement allows the group to take advantage of the strengths of different types of atoms and the types of internal structures they have, Thompson said.

In their experiments, they laser-cool the atoms down to less than 10 mK, and they are generally working with 1,000 to 1 million atoms. “We’re not trying to get down to one atom,” he said. “We want collective physics.” One of the key parameters in their experiments is the cooperativity parameter, C, which Thompson described as, in the case of a single atom inside the optical cavity, the ratio of how much the atom “talks to” the cavity mode versus how much it talks to all the other modes of free space. In their systems, C is about 1 for a single atom. But since they rely on collective enhancement, the ratio of talking to the cavity to talking to the rest of the universe becomes NC, where N is the number of atoms in the cavity. With collective enhancement, the cooperativity parameter can be between 1,000 and 1 million.

With that background, Thompson broke his talk into several parts, first describing the types of cavity-mediated interactions that his group can realize between atoms. Next, he spoke about emulating physics associated with Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) superconductors, using the measurement process to entangle atoms, and realizing an entanglement-enhanced matter wave interferometer. Finally, Thompson spoke about a new collective recoil mechanism his team has observed, and a new approach to breaking through thermal limitations to build very narrow-line-width lasers.

Cavity-Mediated Interactions

Thompson began by describing a simple example of a cavity-mediated interaction, a spin exchange interaction mediated by a detuned cavity. Consider two atoms of strontium, one in a singlet state and one in an excited triplet state. The one in the excited state emits a photon to drop into the singlet state, but before the photon has a chance to escape through the cavity mirror, the other atom absorbs it, moving into the excited triplet state. “So, what has happened in that process is they’ve exchanged which one is in the ground state and which one is an excited state,” he said. “They’ve exchanged their spin states by throwing a photon into the cavity and then another atom absorbing it.”

Recently, he continued, his team has figured out how to go beyond this simple two-body exchange. “We can now engineer three-body interactions,” he said. “For

instance, three atoms actually can flip their spin state at the same time.” They have data showing these sorts of three-body interactions, and they have gone beyond this and have seen signatures indicating that there are four-body interactions present in the system as well. Thompson said that he was leaving out the details of how this is done and really just wanted to provide a flavor of the sorts of things they are doing and to show that they are expanding the types of interactions that they can realize in these systems.

Emulating Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer Superconductors

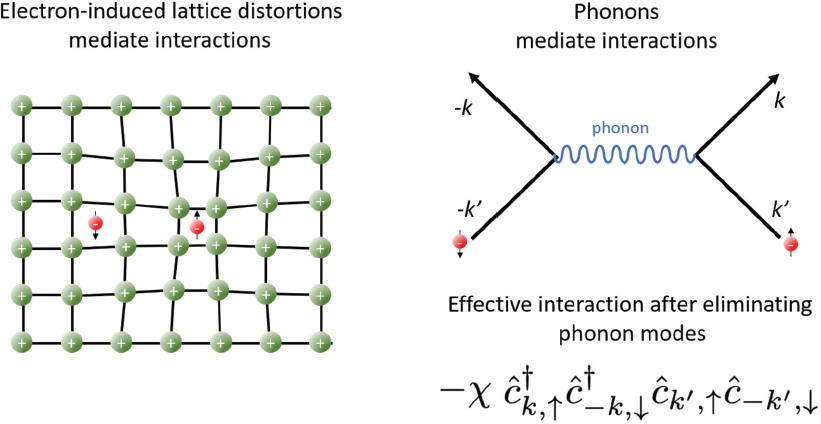

Next, Thompson spoke about how his group has used cavity-mediated interactions of this sort to emulate the dynamical phases of BCS superconductors. He began with an “experimentalist toy model of a superconductor,” with electrons flying through a crystal lattice, creating a distortion in the lattice that drives an interaction between the electrons (Figure 4-1). This distortion of the lattice can also be described in terms of a Feynmann-like diagram where the interaction is shown as an exchange of a phonon (a quantum of vibrational energy. Mathematically, the effective interaction can be described with a four-term Hamiltonian with a term for the attractive potential and three others.

To model this interaction with a cavity-mediated interaction, Thompson explained, the Hamiltonian would be modified so that, among other changes, the

SOURCE: James Thompson, University of Colorado Boulder and JILA, presentation to the workshop, October 3, 2024.

phonon would be replaced with a photon. Specifically, using Anderson pseudo-spin mapping, he rewrote the Hamiltonian in terms of spin operators so that the original problem was mapped onto a spin Hamiltonian where the original states occupied by electrons were identified as spin up and states with no electrons were identified as spin down.

In a superconductor, states with an energy above the Fermi edge tend to be unoccupied, while those below it are generally occupied, and states around the Fermi level are a superposition of occupied and unoccupied; in the corresponding situation for a cavity-mediated interaction, there is a superposition of spin up and spin down states. Similarly, while k represents momentum in the Hamiltonian for the superconductor, it represents a lattice site in the rewritten Hamiltonian.

The rewritten Hamiltonian can be realized in a group of atoms in an optical cavity, and experiments and measurements on that system will offer insights into BCS superconductivity. And one of the nice things about these cavity systems, Thompson said, is that one can get access to observables that are hard to access in other systems. For example, there is a certain amount of leakage of light out of the cavity that can be detected either with photo detectors or with homodyne detection, and it turns out that this leakage is proportional to the BCS gap, which is a quantity researchers wish to measure. So, he said, it is possible to track in real time how the amplitude of the BCS gap energy changes just by measuring the weak amount of light that leaks out of the cavity. This is a much easier measurement to perform, he continued, than other measurements done in, for instance, cold atom systems with degenerate gasses that would offer similar insights into the BCS gap energy U.

Next, Thompson described another way that this emulation of BCS superconductors with atoms in an optical cavity has been used to study superconductivity. Theorists had predicted what would happen in a BCS superconductor if the parameters in the Hamiltonian had a sudden change—were “quenched”—and they saw three different dynamical behaviors. One was a total collapse, where the BCS gap shrank to zero. In a second, the gap was protected and stayed approximately the same. In the third, there were oscillations (Barankov and Levitov 2006; Gurarie 2009).

When experiments were done in an optical cavity to emulate this quenching, they saw the predicted behavior. At very low numbers of atoms in the cavity, the coherence of the atoms (corresponding to the BCS gap) quickly collapsed to zero. But as the number of atoms was increased, the coherence was protected for a long time, which indicated that a transition had been made from the first type of predicted behavior to the second. They also observed the third type of behavior that had been predicted (Davis et al. 2020). “It turns out that people have been interested in seeing this, but it’s very difficult to do in real superconductors,” Thompson said, “because you might want to hit the system with an ultra-short laser pulse to kick the system out of equilibrium, but when you do that, there are all other kinds of

nasty things that can happen beyond just kicking the system out of equilibrium. You can get pair-breaking processes and other things that obscure the physics.”

The experiments offer other insights as well, he said. It is possible, for instance, to see Higgs oscillations at this quench. And it is also possible to redo the experiments done with ultracold gases to emulate the oscillations seen after a quench. The researchers doing the earlier experiments did not know how to measure the gap energy, so they did a kind of radio frequency spectroscopy to measure what they called the spectral gap. The experiments in the optical cavity can measure both—the BCS gap and the spectral gap—and show how they differ.

Looking to the future, Thompson said that the idea in these experiments so far has been to work with systems to emulate other physics by stripping out much of the complexity. “We can start going to more complex systems,” he said. “We can add complexity back in—in a controlled way…. So we think there’s going to be a lot of fun here.”

Entangling Atoms with Measurement

Switching to the topic of entangling atoms via cavity-enhanced measurements, Thompson said, “We’re going to somehow take all these little atoms, and we’re going to connect them with gooey entanglement.” Specifically, he added, his group is interested in entangling atoms for improving quantum sensing.

For a system of N atoms, there is some fundamental quantum fuzziness in the Bloch vector describing the system described by ∆θ∆φ≥1/N, where θ and φ represent the angular positions of the Bloch vector (Figure 4-2). “When I build a quantum sensor of time, of acceleration, of rotation, of magnetic field, of the electric field, that’s what we’re sensing,” he said. “You’ve got to see where this Bloch vector is pointing at the end of your sensing period,” and that inherent fuzziness limits the accuracy of the clock or sensor. However, he continued, by entangling the atoms, it is possible to reduce the noise in one dimension while increasing the noise in the other direction in such a way that the product of the fuzziness in the two directions never drops below the fundamental limit. “So we can make sharper sensors for measuring the universe around us,” he said.

It also turns out, Thompson said, that if a researcher carries out this sort of manipulation and has a phase resolution better than radians, where N is the number of atoms in the system, “then this is also an entanglement witness in the system, and it actually quantifies the degree of entanglement as well.” As an example, he briefly described some experiments where they used microwaves to essentially put every atom in the ensemble in a superposition of spin up and spin down. When they prepare that state, there is some quantum fuzziness along the z direction. So they measure the spin projection Jz using a QND Hamiltonian, which is a Hamiltonian where the cavity frequency shifts by an amount that depends on

SOURCE: James Thompson, University of Colorado Boulder and JILA, presentation to the workshop, October 3, 2024

Jz, and by doing that they get collective information about how many atoms are in spin up versus spin down, but not any information on which atoms are in spin up and which atom is at spin down. “This is really key,” he said. “This is what makes it different from your typical spin projection measurement.” They do a premeasurement of the noise in the spin project, then they carry out the experiment many different times at slightly different polar angles. What they can do, he said, is look at the differential quantity and essentially subtract out the quantum noise. “So now you have phase resolution below the standard quantum limit,” he said. “It works on every trial. It’s conditional in the sense that you have to keep track of the information you gain, but we’re not throwing away events.”

In fact, he continued, this experiment generates more quantum entanglement than any other that he is aware of in any experimental platform, ion trap, superconducting circuit, or other platform. They can get a factor of about 60 beyond the standard quantum limit by using an ensemble of 1 million atoms (Cox et al. 2016; Hosten et al. 2016). “And this technique scales very well with increasing atom number, which is what you want,” he said. “You want your life to get easier with increasing atom number.”

This sort of entanglement has also recently been used, Thompson noted, to show that they can improve an optical lattice atomic clock that’s operating with a frequency precision of 10−17 (Robinson et al. 2024).

Entanglement-Enhanced Matter-Wave Interferometers

Matter-wave interferometers are another type of quantum sensor that are very important, Thompson said. In such an interferometer, pulses of light put atoms in a superposition of having absorbed light and not having absorbed light—and therefore, because light carries momentum, having recoiled and not having recoiled. “You can actually have these atoms travel along two different paths, use pulses of light to recombine them, and get an interference signal,” he explained. This is single atom physics, he said. “You may run a million atoms through your interferometer, but essentially it’s just a million copies of the same experiment running in parallel.” Matter-wave interferometers can be used in a number of different, incredibly powerful technology applications, including navigation, gyroscopes, accelerometers, and gravimetry. And researchers use them in a wide variety of ways, including measuring the fine-structure constant, testing quantum electrodynamics, and detecting gravitational waves.

To try to improve the performance of matter-wave interferometers, Thompson’s team has run them inside of their optical cavities. “We send pulses of light along the cavity axis while the atoms fall under gravity,” he said, which allows them to put atoms in superpositions of different momentum states and move them to very large, separated momentum states. First, they had to show that they could do this in a high-finesse cavity, which had never been done before. Once they had accomplished that, they used quantum non-demolition measurement, or “one-axis twisting,” to generate entanglement, and then they injected that entangled state into an interferometer and showed that they had enhanced precision at the output. “That’s the first time that’s ever been achieved,” he said, “so we think this is a real milestone.”

Collective Recoil Mechanism

Noting that he had been focusing on spin degrees of freedom and interactions between spin states, Thompson said it is also possible to get interactions between momentum states. In particular, if 2 qubit states are two different momentum states, then it is possible to use lasers to induce a scattering event into the cavity that will cause the atoms to flip their momentum states. “It’s just like an exchange interaction, but now it’s between momentum states,” he said.

When these interactions are not turned on, the coherence time in the system decays relatively rapidly, but once the interaction is turned on, the coherence lasts for longer. “What’s up with that?” he asked. The reason for the collapse of coherence, he explained, is that the atoms go into a superposition of different momentum states, and their atomic wave packets no longer overlap with each other. The fact that the coherence is extended by the interactions implies that the wave packets are not separating anymore. “That’s weird,” he said.

To show how weird that is, he offered a gedanken experiment. First, imagine a collection of N atoms that are not interacting via the cavity mode, and a single photon is shot into that cloud and gets absorbed. A short amount of time later, a single photon with the same momentum as the first one will come flying out of the cloud. That is just conservation of momentum, he observed. But now suppose that the N atoms in the cloud are interacting through momentum-exchange interactions. In that case, if a single photon is shot into the cloud, the whole cloud will recoil collectively. “As an experimentalist, this is huge,” he said, “in the sense that this is really a collective recoil mechanism, kind of like what’s used to suppress Doppler dephasing in quantum sensors like Mossbauer spectroscopy or Lamb–Dicke spectroscopy.” Furthermore, he added, his team has recently extended this from a matter-wave interferometer and seen the same physics on an optical clock transition.

Breaking Thermal Limits by Hiding Phase Information in the Atoms

The last project that Thompson described is an effort to break through thermal limitations on achieving very-narrow-line-width lasers. The problem is that tiny movements of the mirrors scramble the phase of the light inside that cavity, and the approach his team is using to minimize that issue is to hide the phase information of the laser in a collective state of the atoms. “This may not be your problem,” he said, “but it turns out there’s a whole community that has spent multiple decades with this problem.” The issue is also of interest to the community working with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO).

Thompson did not describe the approach his group is taking, but he said that it is a completely different approach from what has been done before and, if it works, it would be “a huge quantum leap in our ability to make very precise measurements.” Currently the best coherence lengths of lasers are of the order of the distance from Earth to the Moon; his team is hoping to realize coherence lengths more like the distance from Earth to the Sun.

If their efforts bear fruit, he said, they may be able to go from lasers with pulsed superradiance to those with continuous superradiance and laser light that has an imprecision of 10−18 at 1 s. This would have important applications in high-bandwidth geodesy, gravitational wave detection, and searches for dark matter, he concluded.

After the presentation, Toor asked how the work Thompson described could be used for quantum computation. He answered that he is not in the computation field—he is interested in quantum simulation and quantum sensing—and he does not believe that the optical cavities he works with are well suited for quantum computation. However, he added, laser-cooled systems may be one of the leading platforms for quantum computing, but it would likely involve using Rydberg-mediated interactions and tweezers, not optical cavities, to do the computations.

PHOTONIC NETWORKS

Nick Peters, the head of the Quantum Information Science Section at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, spoke about photonic networks, beginning with why networks are valuable. “We are going to get the most out of our quantum resources if we can have quantum networks between those quantum resources,” he said. Metcalf’s law says that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of users, so joining resources in a network greatly increases the value of those resources. Furthermore, he added, for a quantum network the value may well grow exponentially with the number of users.

In building a quantum version of today’s Internet with a large number of interlinked quantum devices, photons will play a key role in carrying signals, Peters said (Figure 4-3). There are two major approaches that people talk about for how to transmit quantum information with photons, he continued—through free space and via wave guides. For wave guides, the approach that most people are considering today is to use standard, single-mode optical fiber, he added. However, depending on what types of quantum technologies will be interconnected and how far apart they are, people are likely to choose different ways to carry the photons.

Fiber transmission has a lot of signal loss, Peters noted, but it has a major advantage that the optical fibers can be curved rather than requiring the communication to follow a straight line, so that “we can bend it around any place we want and get our photons to locations where we can put our quantum repeater stations.” It is more difficult in free space, such as going from a low Earth-orbit satellite to the ground, he said, because repeater stations will probably not be installed between the two. “It’s possible, but not super likely.”

Going into further detail about the difficulties posed by signal loss, Peters first mentioned the no-cloning theorem, which says that it is not possible to just boost the quantum signal. “We add noise, and it screws everything up,” he said. Then Takeoka and colleagues (2014) showed that there is a fundamental rate/loss tradeoff bound. That paper is foundational, Peters said; although it was initially focused on quantum key distribution, the bound was later generalized. The bottom-line message from the paper, he said, is “everybody needs to be working on quantum repeaters if we want to have important, scalable quantum networks.”

Concerning signal loss with photons, he continued, most people focus on the channel loss, that is, the loss due to either diffraction in free space or the fiber loss, “but there are a lot of other losses that count and they do hurt you.” The other issues include efficiency in photon generation or in the detection of the photons as well as issues arising from manipulation of the photons, such as carrying out two-qubit operations between photons.

The fact that photons do not interact strongly with one another is both a strength and a weakness of using photons, he said. The weak interaction makes

SOURCES: Nick Peters, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, presentation to the workshop, October 3, 2024. Earth background from the Department of Energy.

them great for sending down an optical fiber, for instance, but then it is difficult to make two-qubit gates with photons. In designing quantum networks, one must not only deal with the quantum issues but also figure out how to make things work. “You have to look at the other physical constraints as well as the engineering constraints and how they impact your ability to do the quantum part of the protocol,” he said.

In speaking about quantum repeaters, there are two basic types of approaches, Peters said. The first, quantum teleportation, distributes entanglement over dis-

tance. It could be, for instance, a two-mode entanglement, either qubit entanglement or a two-mode continuous variable entanglement, such as amplitude and phase. Distributing the entanglement is a non-deterministic process, he noted, because there is channel loss. “What we do is we’ll grab our entanglement, we’ll store it in a memory, and then that memory is holding it until we need it,” he said. “And as that’s holding it, it’s decohering.” To deal with that, one can add additional entanglement and do operations on the stored entangled excitations which depend on exactly how they’re stored and also do things like entanglement purification or concentration. “We’ll take a large ensemble of imperfect entanglement and distill it down into a smaller ensemble of better entanglement so we can use that for our teleportation resource,” he continued, “and we’ll teleport quantum information just when we need it.”

The other major approach is to encode the quantum information in a quantum error correction code and then transmit that encoded state of multiple photons. Since the different photons could be distinguished by their different frequencies, Peters said, “I could pull the different photons apart and then do my quantum repeater station at the next node.” The basic idea is that the code itself protects the quantum information against both loss and operational errors.

Offering an example of how one might do this, Peters said one would start with input modes that are resource states; these could be single photons or squeezed states of light, for instance. One does some unitary operation on these input modes and has some detectors that will indicate conditional success in encoding things as desired. “Then,” he said, “you’ve created a heralded version of your quantum error correctable state”—that is, a version that is accompanied by a signal of success.

Noting that he had been vague about the details because “there are lots of ways to do the hard parts,” he said that one option was to perform linear optical operations, but if that is the choice, it is necessary to have some kind of nonlinearity in order to get a strong interaction. In linear optical quantum computing, one gets that sort of strong interaction by using quantum interference and then detection. But in general, he continued, to do these types of linear optical operations well, one needs photon sources that emit photons at specific wavelengths and, furthermore, that will emit exactly one photon and do it with a very high probability. “It turns out that is very, very difficult to do,” he said, noting that the annual Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics will have hours of talks on how to build single photon sources.

One possible way to address the issue with linear optical operations, Peters said, is to use what he called a linear optical frequency processor, noting that the steps taken to enable fault-tolerant quantum networking are pretty much the same as what is needed to enable linear optical quantum computing. The approach they use starts with a system where they define their logical qubit in two different frequency modes of light. Then they apply an electro-optical modulator, which uses

microwave energy in an electro-optic crystal to spread out the frequency of the input photon. Next, they send the photon into a pulse shaper, which allows them to individually tailor the relative phases of the different frequencies. With the right phases, he said, it is possible to effect arbitrary unitary operations. “Then you take those different frequencies of light with the specific phases imprinted on them, and you can use another electro-optic modulator to do interference and constructively or destructively interfere, depending on what your operation is, the things together to effect the operation that you want.”

Peters’s team tested this approach experimentally and, among other things, created a two-qubit gate. However, he added, that gate was not deterministic, and to make it deterministic it will be necessary to add an additional single photon. “That’s one of the weaknesses of linear optical types of quantum computers—it’s not deterministic unless you have additional resources,” he said.

The reason that his team picked the particular set of technologies for the experiment, Peters said, is because they are all standard components in the telecommunications world. This has the benefit that the technologies can be easily acquired and are very reliable. The disadvantage of these technologies is that they are made for telecommunications systems where a 50 percent loss of signal (or 3 dB) is not a big deal—one just puts the signal through an optical amplifier to bring it back to the original level. It is more of a problem for the quantum signals, he said. “If I have to have a network of two of these phase modulators and one of these pulse shapers, you’re looking at about 10 dB of loss, and so that’s a lot, especially in the context of trying to build things that are fault tolerant.” Instead, he would like to have much less than 50 percent loss so information can be retained between repeater stations.

Peters then briefly spoke about the practicality of putting quantum signals on the same optical fibers used for digital signals. Current optical fibers have a tremendous amount of bandwidth—almost 10 THz—and the available channels are typically not all taken up by digital signals, for a couple of reasons. First, if classical optical signals are spaced too closely together on the optical fiber, one gets four-wave mixing effects. Second, if a fiber is accidently broken by, say, a shovel or backhoe, it is important that the laser light that comes from it is eye-safe. The bottom line is that there is a great deal of available bandwidth on optical fibers to use for quantum communications, he said. “And so the question is, ‘Could I put my quantum signals on that same fiber as my classical signals?’ and it’s a little harder to answer that than you might at first think.”

In addressing the issue of putting quantum signals on existing fiber optic lines, Peters and his team first approached it in the context of quantum key distribution (QKD). QKD is probably the mature protocol that people talk about in quantum communications, he said, although “it is still not mature enough for people to say it’s good.” Creating a separate infrastructure for QKD would be very expensive, so the team examined the feasibility of sharing the existing fiber optic system. “When

you do that, it puts constraints on where you put your classical signals as well as how you route them,” he said, and his team showed that it would be possible to put a QKD signal in the O-band (1260–1360 nm), and for any noise that appears, the conventional signals around 1550 nm would have little effect on the quantum signals.

What about putting quantum signals on the same band as classical signals, he asked, given that there is very low transmission loss in that band? It turns out, he said, that it is impossible in that band to avoid the impact of Raman scattering of the classical signal. “In the context of doing direct detection with qubits, even using very narrow band filters, it [Raman scattering] adds noise to your system, and it’s very difficult to get rid of it.”

One of the things that might help to get around the issue of nondeterministic entanglement transmission, Peters said, is to encode more entanglement in the photons than just a single degree of freedom. His team has been studying hyperentanglement, which he defined as encoding multiple degrees of freedom on a pair of photons for a long time, and his team has shown that it is possible to build hyper-entangled sources and that these generate photons over a broad range so that they can use the bandwidth in optical fibers.

Another area where hyper-entanglement might be useful, he said, is in the idea of entanglement purification. “If we have extra entanglement on our pair of photons,” he said, “that may be useful to help mitigate the decoherence that we might get in one of these quantum repeater systems.” As a steppingstone toward that, his team showed that it is possible to build a good controlled-NOT gate in the context of having this entanglement. Ordinarily, he said, one might not think that hyper-entanglement would be useful for a system where one wants to do teleportation because when there are extra degrees of freedom, it usually causes problems because one ends up averaging over those degrees of freedom. However, he continued, because they can manipulate that frequency degree of freedom directly by using the linear optical gates, they think that they can turn something that has been a challenge into something they can use to make the problem easier to address.

As an aside, Peters showed a photo of the quantum network test bed at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and said that the test bed has recently installed a long fiber network that allows them to test systems up to 300 km in length. Using this practical fiber network instead of putting everything on a tabletop in a laboratory forces the researchers to figure out techniques that will allow their experiments to work in a more practical setting, he commented.

One useful technique for working on such practical networks is Procrustean filtering, which Peters described as a technique where one can take an ensemble of entanglement that is noisy, such as from crosstalk from classical-level signals, and reduce that noise by applying filters in a way that takes into account how the noise appeared in the ensemble. The result is an ensemble that has fewer pairs

coming through, but for which the quality of the ensemble is higher. His team used Procrustean filtering to improve an ensemble of entanglement enough that it could, in principle, be used for a protocol for which it would not otherwise have worked.

In closing, Peters said that he believes it is very important to look into continuous variables for possible use as a repeater engine to enable quantum repeaters. In a recent experiment, he said, his team generated two-mode squeezing and distributed it over a fiber network and then independently measured that squeezing. This could be a first steppingstone, he said, to one day being able to build quantum repeater networks and distribute squeezed states and squeezed-state resources in a way that could be practically useful. For instance, he suggested, it might make LIGO work better than it currently does, as LIGO is now a classical network of quantum sensors.

After the presentation, Thompson asked Peters about the thinking in the quantum networking community about using local quantum networks with local interconnects versus long-distance applications. “The idea,” Peters replied, “is that if I have things that are sitting next to each other, maybe I don’t have to pick a wavelength that goes down an optical fiber, because my optical fiber will be so short I can pick whatever wavelength I want. And that’s absolutely the case.” There is currently disagreement about the need for optical interconnects, he said, but “for most people, if I can build something that’s closely spaced, I don’t have to do frequency conversion, so that removes a complicated step.” It is absolutely the case, he continued, depending on how devices will be used, it may be possible to put them close together, which may be cheaper than connecting them over long distances. On the other hand, he said, there are also some applications where devices need to be placed very far apart, and he mentioned LIGO as an example where quantum processors must be spaced far apart to get rid of local noise in order to use them more effectively.

QUANTUM SIMULATION

Immanuel Bloch of the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Physics spoke about quantum simulations using ultra-cold atoms. As background, he noted that a major challenge in modern physics is developing a fundamental understanding of quantum many-body systems in and out of equilibrium. Both quantum computing and quantum simulation will play a major role in this quest, he said, and each has its particular advantages.

Quantum computing, which is a digital approach, involves creating a model of the Hamiltonian operator of interest and solving that model by carrying out calculations through a series of elementary gate operations. This digital approach is universal in the sense that it can solve any system, but it is resource hungry. Furthermore, it is necessary to get the full many-body wave function exactly right,

because if there is a single error on the wave function, the complete calculation might be wrong.

Quantum simulation, by contrast, is an analog approach and involves building a system that will implement the desired Hamilton directly. This is a very powerful approach, Bloch said, but it is not universal. “It is limited because you can only simulate what you can build in the lab.” However, he noted, a recent paper by some of his colleagues in Munich, Germany (Trivedi et al. 2024), showed mathematically how one can achieve quantum advantage in such quantum simulators. “You are generally dealing with systems which have no error correction, which have extensive amount of errors,” Bloch said, “but still, because generally you’re measuring intensive quantities in your system, you can actually, in many, many applications, reach quantum advantage.” It was very important to clarify this for the community, he added.

Next, Bloch offered some background on the past 25 years of work in the quantum simulation of strongly correlated states of matter. He first became interested in the field because of a 1998 paper by Jaksch and colleagues that modeled a transition from a superfluid to a Mott insulator in an optical lattice containing an ultracold dilute gas of bosonic atoms. The field has grown in the intervening years, and now a wide variety of quantum simulations have been studied across a number of different platforms, including ion traps, optical lattices, Rydberg tweezers, and superconducting devices. The focus of his talk, he said, would be on work in neutral atom systems, mostly in optical lattices.

In these neutral atom systems, the atoms are trapped in optical fields and made to interact with each other in a variety of ways—through collisions, dipolar magnetic or electric interactions, Rydberg dipole–dipole interactions, and cavity-mediated interactions, among others. These various types of interactions have different connectivities and offer very different possibilities of engineering interactions in the neutral atom systems.

Typically, Bloch continued, his group works in optical lattices, which are created by interfering laser beams. They put cold atoms into a lattice, and the atoms will move around. In these systems, he said, the quantum statistics matters. “It actually matters whether you put fermionic atoms or bosonic atoms in there, and that makes this a rather unique system,” he said. “I think the only other system where you have this possibility to study fermions directly is quantum dot platforms for quantum simulations.”

With today’s technology, it is possible to change from one lattice configuration to another at the push of a button, Bloch said, “so you don’t need to have intricate rearrangement of your laser beams.” With a single setup, researchers can move from square lattices to hexagonal lattices, triangular lattices, Kagomé lattices, superlattices, spin-dependent lattices, or flux lattices. They have full dynamical control over the lattice depth, geometry, and dimensionality. Such control is extremely

valuable because the physics of these systems depends very much on their geometry and other qualities.

A second crucial development in the field, Bloch said, was quantum gas microscopy, which makes possible an atom-by-atom detection of fermionic or bosonic atoms in optical lattices. It works on a large array of particles with very good signal-to-noise ratio, and the detection can be done in spin- and density-resolved ways simultaneously. “So we can tell whether it’s a spin-up or spin-down atom at a site, or whether there’s a vacancy or doubly occupied site there.”

This ability to detect the positions of particles in the lattice along with their properties allows researchers to essentially take a photo of the many-body wave function, Bloch explained. “You have a many-body wave function as a superposition of different configurations,” he said, and the quantum simulators make it possible to repeat an experiment thousands of times, measuring the configuration each time. This produces a probability distribution of configurations, which allows researchers to calculate “multi-point correlation functions that are simply inaccessible in real condensed matter materials,” he said.

This capability can be applied in a variety of ways in different fields. For instance, his team is interested in how dopants, holes, or doubly occupied sites that they introduce into the system interact with a magnetic background in the system.

To illustrate, Bloch showed images from a simulation in which his team put fermionic atoms in a lattice—a flat central region where they did the experiment—surrounded by and connected with a reservoir. “And the depth of the optical potential between the reservoir and the flat region—that’s what you would do in a condensed matter experiment by applying a voltage,” he said. “By just changing the depth from the reservoir to the flat region, you can actually change the chemical potential and tune through different quantum phases of matter.” In the simulation, when the system is tuned into a Mott insulating phase, that phase is clearly distinguished by having a higher average density than the surrounding metallic region with a lower density. And the transition from the Mott region in the center to the metallic region on the outside is clearly visible in the ring of fluctuations. The ability to see this transition is “really remarkable,” Bloch commented. Furthermore, if one maps the spins of the individual particles, the resulting map looks like a checkerboard, with spin-up and spin-down particles alternating consistently and showing that anti-ferromagnetic correlations extend across the entire system.

From here, Bloch said, one can introduce dopants into the systems to address fundamental questions that condensed matter scientists have been considering for decades, such as what happens when one has single dopants in such an anti-ferromagnetic background. When a hole is placed in such a background—for instance, if the hole moves—it destroys the anti-ferromagnetic background by causing the up and down spins to move; thus, the hole cannot move indefinitely because that would cost a lot of energy. “The hole cannot separate from the spin

it leaves behind, and this leads to a linearly confining potential,” Bloch said. “New particles are born, which are basically like the mesons in nuclear physics. And here, these quasi-particles are called magnetic polarons.”

He then showed a diagram illustrating a polaron and how spin correlations are modified by the presence of a hole, as determined by a quantum simulation. The simulation reveals a very intricate structure that extends a long way out from the hole, he commented. He added that his team is working with colleagues in Munich to see if that polaron can be calculated with quantum Monte Carlo methods.

Bloch also mentioned briefly research from other groups that have pushed the field forward. Martin Zwierlein’s group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has worked a lot on attractively interacting fermions. The groups of Markus Greiner at Harvard University and Waseem Bakr at Princeton University have exciting work in frustrated systems and kinetic magnetism and kinetically induced polarons. And Jian-Wei Pan’s group in China is doing remarkable work realizing large-scale, three-dimensional systems containing a million atoms at very cold temperatures. This is an exciting direction for the field, Bloch said.

Concerning where the field of equilibrium quantum simulations currently stands, Bloch said that it is now entering a new phase, and the next few years should see experiments pushing into the so-called pseudo-gap regime with very complicated questions to answer. “What is amazing now with the quantum simulation approaches,” he said, “is that we can combine macroscopic thermodynamic quantities from material science and putting microscopic, real-space measurements beneath that, revealing hidden orders, multi-point correlation functions, and fluctuations in these systems.” Connecting the microscopic picture with macroscopic quantities will open a whole new and exciting research direction in the future, he predicted.

Next, Bloch offered a brief overview of quantum simulation work that has been done in non-equilibrium dynamics. A typical approach, he said, is to apply a global quench to a system so that the global Hamiltonian parameters are suddenly changed, bringing the system strongly out of equilibrium and inducing dynamics. One early experiment his group did was to look at what happens when a quench is applied to a Mott insulating state, sending it to a regime of weaker interactions. This generates correlated quasi-particles like Bell pairs of double bonds and holes that race through the system in opposite directions, he said, and the speed at which they can race through the system is bound by the famous Lieb–Robinson bound predicted in the 1970s (Lieb and Robinson 1972). The experiments of Bloch’s group marked the first time that bound could be measured.

A good example of a local quench is an experiment on spin–charge fractionalization, where researchers take a one-dimensional, anti-ferromagnetic fermionic chain and removed a single electron from the system. This disintegrates the electron into a spinon and a chargeon, and by using quantum gas microscopy, the researchers could see this fractionalization process in real space in a time-resolved

way. The work provided a direct proof that the spinon had been removed from the chargeon, which was a direct proof of spin–charge fractionalization observed in real space. It was, Bloch observed, “a nice new way to observe these very well understood phenomena but with completely new detection methods.”

In the area of statistical physics, he continued, one highlight experiment from a group at Harvard University examined the question of how isolated quantum many-body systems actually thermalize. The group developed a method—basically Hong–Ou–Mandel interferometry on a many-body level—in which they interfered two identical copies that had undergone some time evolution, and this allowed them to infer the Rényi entanglement entropy, which bounds the von Neumann entropy. They showed that the von Neumann entropy basically corresponds to the usual thermal entropy from statistical physics, and they characterize thermalization in the system. “So locally the system looks thermal,” Bloch said, “but globally it still remains in a pure state.”

Next, Bloch said that the ability to take snapshots of the systems makes it possible to measure quantum transport atom by atom. “If you have many repetitions of an experiment and you look at local observables or subsystems, you actually now have access to the full counting statistics of transport measurements,” he said. “So you can not only measure the mean number of particles that have been transported through a certain region in space, but you can actually also look at fluctuations … and basically then look at the statistics of that.” This provides a wealth of information characterizing quantum transport.

Bloch closed his survey of applications of quantum simulation in non-equilibrium dynamics by mentioning two important experiments. One looked at high-temperature transport in Heisenberg magnets and found that for two-point observables, the system looks as if it falls into a special Kardar–Parisi–Zhang (KPZ) universality class, but for fourth-order moments this does not seem to be the case. “So we have really strange regimes of transport where we believe there’s a partial emergence of KPZ universality class in the system, but not full emergence,” he said, “and we don’t really understand what kind of universality classes are at heart here, and maybe they’re also completely new universality classes.”

In closing, Bloch offered a look ahead. Currently many people are pursuing the digital model of quantum computing, while others are exploring the analog model of quantum simulation, and perhaps, he said, the ideal would be to apply the best of both worlds. That is, researchers can harness the very long coherence times and coherent evolution found in analog quantum simulation but combine that with the very powerful digital readout of preparation methods. “And there are actually very many exciting directions that people are pursuing in this context,” he said. “One is, for example, the work of Adam Kaufman in Boulder, who’s combining the rich world of optical tweezers with that of optical lattices that I introduced.” Bloch also mentioned work done in optical cavities, as had been described earlier

in the workshop by James Thompson. Finally, Bloch pointed to the new field of sub-wavelength arrays of quantum emitters. It is, he said, “a very nice regime for open, driven quantum systems where we have a strong cooperative response when we bring quantum emitters closer than the wavelength of light at which they interact.” Such systems make it possible to do the sorts of things that Thompson described doing in optical cavities but without the physical mirrors, Bloch said; one could, for example, have cavities of strongly cooperatively interacting mono layers of quantum emitters, whether atoms, quantum dots, of some other quantum emitter. This type of system should be explored more deeply in the future, he said, as it has great potential for new types of quantum matter–light interfaces and new kinds of entanglement generation schemes.

After the presentation, Charlie Marcus asked Bloch about how one measures the degree of entanglement versus simply knowing that it is there. Bloch said that it is very difficult in the systems of thousands of particles that he works with. One approach is to measure the entanglement entropy, but that typically only works for smaller size systems, he said. More generally, he continued, the standard methods that people use for measuring entanglement will fail for these large systems. “You can do that maybe for 50 atoms or something, or 50 superconducting qubits,” he said, “but not for systems of thousands of particles.”

DISCUSSION

Toor began the discussion by asking Sarang Gopalakrishnan of Princeton University, who would be giving a presentation in the fourth session, to say a little bit about what his group has been doing and how it relates to what Bloch had been talking about. Gopalakrishnan began by saying that he agreed with the perspective that Bloch had laid out. In particular, he said, in thinking about the real objectives in the quantum simulation of many-body systems, “we’d like to isolate the mechanisms behind the actual phenomena that are going on in a way that allows us to make the effects we care about stronger.” That raises the question of what information researchers need, he said. “Do we need to know about entanglement? How much resolution into the microscopic details of physics do we actually need? … What do we actually want to learn from these simulations? and How do we go about learning it?”

Bloch added that, for him, the value right now is mostly to be found in the interplay between theory and experiment. In working on fermions, for instance, researchers are “benchmarking the best numerical methods that are out there against the output from the quantum simulators to check them against each other.” In doing so, he said, the field is making progress in understanding these systems better and understanding the results of experiments because researchers have completely new observables to work with, which is where the quantum systems show a lot of potential.

Noting the interest from industry in quantum science, Toor asked how the current research in the field may affect industry. Thompson answered that work in the field of quantum sensing is closer to having an impact on experiments outside of quantum science itself. More generally, in terms of commercialization, he said he believes that the work in quantum science is going to lead to real technologies. “I think companies are going to deliver products,” he said. “They’re going to be on airplanes, they’re going to be on submarines.” In particular, the enhancements that can be made to these technologies by figuring out how to extend their precision will be a “near-term win,” and they may be one of the things to help the nation see quantum science as something of value that it should continue to invest in.

On the research side, he said that currently there is an entire ecosystem of research with a large focus on quantum computing, which is important in providing jobs for students in the field. In the past, he said, many of the PhD graduates in the field would go into management consulting, finance, or other unrelated areas. “And therefore, while we were training PhD students on how to think, we were not maintaining a broader community outside of academia who were thinking about these problems and solutions to them.” The current large-scale, high-profile commercial efforts in quantum computing are extremely valuable because they are making it possible for the current cohort of very talented young people to stay in the field “and think long term about solutions to these very hard problems on a scale that is not suited for university efforts.”

It is impossible to predict whether quantum computers will ever emerge, he continued, but he himself is optimistic, even though it is a really hard challenge. And part of his optimism comes from the role that large companies are now playing, which he predicted will have “a payoff in terms of the long-term intellectual development of this field that expands beyond what we can do in universities.”

Charlie Marcus said he agreed with everything that Thompson said but wanted to add that it is important that funding agencies recognize the value of long-term projects for universities as well.

Thompson followed up on that by saying that some of the questions about scalability are best asked in the context of companies, while the role of universities and academic institutions is to be working on the next big idea. Companies are not the best place to work on that next big idea because there is so much pressure just to get something working and ready for market. Funding agencies should be more focused on planning for the future, he said, and they should recognize that the role of academic institutions is critical for this. “I’m not advocating against funding the development of technologies within traditional physics departments and maybe engineering departments now,” he said. “That’s also very important. But I think we really have to be planting the next generation of ideas.”

Marcus commented that this sort of division of labor between academia and industry has a silver lining. “In my experience in the solid-state world, there’s often

a drudgery phase,” he said, “particularly when you want to scale long after the idea has already been demonstrated and the paper has been published,” and this phase is often not as intellectually stimulating as the discovery work. “And so I think that with the existence of industry and a lot of engineers who are working in their day jobs to get things to scale, we can have our students working on things which are a higher percentage of just intellectually stimulating work, which then gets handed off when it’s done.”

Prineha Narang of the University of California, Los Angeles, asked about ways that the current work in coherent systems might provide insights or techniques that researchers in other areas of physics could use. Bloch said that there have certainly been examples of longstanding open questions from other fields being closed because of quantum simulation efforts. Gopalakrishnan added that quantum information and tensor networks have had an immense impact on the way that modern string theorists work, and papers on the black hole information paradox have a number of ideas that are completely recognizable to quantum scientists. Thompson noted that scientists looking for gravitational waves with LIGO have used entanglement to enhance their ability to detect those waves.

Edward Parker from RAND Corporation asked if, in the medium term, quantum simulation on quantum emulators is likely to get so good that it just completely replaces quantum Monte Carlo, DMRG, and tensor networks, and there is no reason to ever do digital simulation again. “Or,” he continued, “will we be in this murky ground where the quantum emulators are way beyond the ability to classically check them” so that when the emulators disagree with, say, DMRG results, there is no way to know which is giving the more correct answer? Thompson replied that theorists are pretty clever and that one of the advantages of quantum simulation is that it “gives something for the theorists to benchmark their techniques against and get even more clever.” Physicists prefer not to get their answers from a black box, he continued, because it does not give them any physical insights, but he said that, still, theorists can “use the black box to help us understand how to be more clever.”

REFERENCES

Barankov, R.A., and L.S. Levitov. 2006. “Synchronization in the BCS Pairing Dynamics as a Critical Phenomenon.” Physical Review Letters 96(23):230403.

Cox, K.C., G.P. Greve, J.M. Weiner, and J.K. Thompson. 2016. “Deterministic Squeezed States with Collective Measurements and Feedback.” Physics Review Letters 116(9):093602.

Davis, E.J., G. Bentsen, L. Homeier, T. Li, and M.H. Schleier-Smith. 2019. “Photon-Mediated Spin-Exchange Dynamics of Spin-1 Atoms.” Physical Review Letters 122(1):010405.

Gurarie, V. 2009. “Nonequilibrium Dynamics of Weakly and Strongly Paired Superconductors.” Physical Review Letters 103:075301.

Hosten, O., N.J. Engelsen, R. Krishnakumar, and M.A. Kasevich. 2016. “Measurement Noise 100 Times Lower Than the Quantum-Projection Limit Using Entangled Atoms.” Nature 529(7587):505–508.

Jaksch, D., C. Bruder, J.I. Cirac, C.W. Gardiner, and P. Zoller. 1998. “Cold Bosonic Atoms in Optical Lattices.” Physical Review Letters 81:3108.

Lieb, E.H., and D.W. Robinson. 1972. “The Finite Group Velocity of Quantum Spin Systems.” Communications in Mathematical Physics 28:251–257.

Robinson, J.M., M. Miklos, Y.M. Tso, C.J. Kennedy, T. Bothwell, D. Kedar, J.K. Thompson, and J. Ye. 2024. “Direct Comparison of Two Spin-Squeezed Optical Clock Ensembles at the 10−17 Level.” Nature Physics 20:208–213.

Takeoka, M., S. Guha, and M. Wilde. 2014. “Fundamental Rate-Loss Tradeoff for Optical Quantum Key Distribution.” Nature Communications 5:5235.

Trivedi, R., A. Franco Rubio, and J.I. Cirac. 2024. “Quantum Advantage and Stability to Errors in Analogue Quantum Simulators.” Nature Communications 15:6507.