Frontiers of Engineered Coherent Matter and Systems: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 2 Overview of Engineered Coherent Matter and Systems

2

Overview of Engineered Coherent Matter and Systems

The workshop’s first session offered an introduction to and overview of the field of engineered coherent quantum matter and systems. Three speakers provided overviews from three different perspectives, after which the speakers and audience members took part in a discussion session.

A BIG PICTURE OVERVIEW

Planning committee member Nadya Mason, dean of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago, began by providing what she called a “big picture overview” of how the workshop was conceived and created. The germ of the idea for the workshop came, she said, from workshop chair Charles Marcus, University of Washington, who noted that a number of people in the condensed matter physics community were working on different aspects of coherent quantum networks and suggested that perhaps there might be some interesting ideas that would arise from getting people together to talk about their research.

For example, a number of researchers—including Mason and Marcus—had been carrying out research on Josephson junction arrays (see, e.g., Lesser et al. 2024). “These are very old systems,” Mason observed, “and yet there are new ideas there about how, for example, to look at topological phases using Josephson junction arrays that are locally controlled and to control interactions in them.” Similarly, she continued, there has been tremendous progress in qubit systems and using large-scale coherent entangled systems to simulate different quantum materials and different properties.

It was natural to ask, she continued, if there were any new scientific ideas, new technologies, or new connections that researchers could make by talking together about these different types of systems. The timing seemed particularly auspicious, she said, because of recent progress in fabrication, in capabilities, and in theoretical understanding relevant to these systems. “So how do we put that together in a new way?” she asked. “And how do we think about it?” Thus, the decision was made to hold the workshop.

In explaining what topics the workshop would cover, Mason began by defining the terms in the workshop title Frontiers of Engineered Coherent Matter and Systems. Coherent matter and systems, she said, are systems of interacting quantum elements that are coherent—that is, that do not lose energy to the environment at some longer time scale. Because the systems do not lose energy to the environment but instead retain their coherence, they interact in a way that can lead to properties and behaviors that are different from non-coherent systems. The term “engineered” was included in the title, she said, because engineering such systems makes it possible to design a system’s potentials and thus control its interactions on a microscopic level. Just as the development of heterostructures provided materials scientists with new capabilities and “playgrounds” compared with bulk materials, she said, engineered coherent systems offer “new playgrounds to control interactions and to induce different types of states.”

The workshop would be considering two related but different types of coherent systems, she said. The first would be active quantum materials, which she described as being “governed by designer Hamiltonian systems, where you really know and can design and control the potential states.” Such systems might have local interactions, for example, but they are coherent. The second are systems in which measurements also steer the evolution of the system, in addition to the Hamiltonian; an example would be many-body entangled states where making a measurement affects the evolution of the system. One question the workshop will examine, she said, is the connections between these different types of systems. Are there, for instance, things that comparing one with the other will help illuminate?

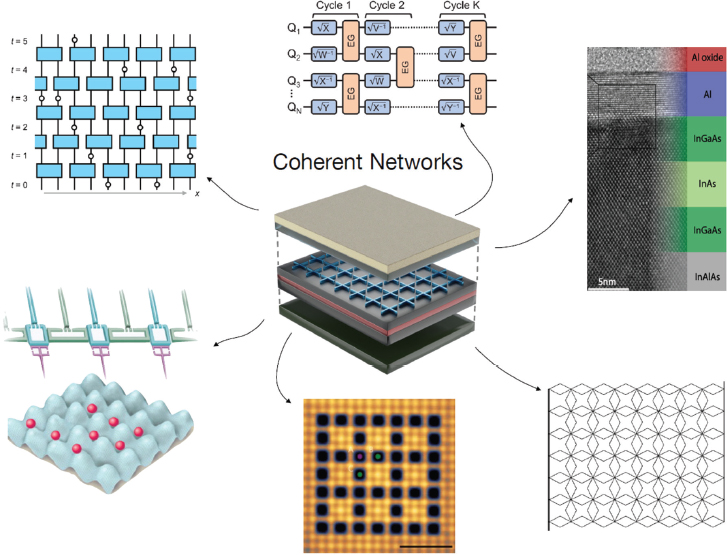

Next, Mason showed an “inspiration board” that she and Marcus had assembled for the workshop (Figure 2-1). “We just put together a whole bunch of ideas, papers, and thoughts about what are the systems that might be relevant to understanding these sort of coherent systems and networks,” she said, and she offered a few details about each entry.

As exemplified by the entry in the upper righthand corner of Figure 2-1, for instance, there has been a great deal of improvement in making heterostructures of semiconductors and superconductors. This in turn has given researchers new ways to tune Josephson junction arrays, she said, allowing them to “start thinking about creating controllable interactions in these sort of systems, to simulate topo-

SOURCES: Nadya Mason, University of Chicago, presentation to the workshop, October 3, 2024. Images clockwise: (top left) Reprinted with permission from Y. Li, X. Chen, and M. Fisher, 2019, “Measurement-Driven Entanglement Transition in Hybrid Quantum Circuits,” Physical Review B 100(13):134306, http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.100.134306. Copyright 2019 by the American Physical Society; (top center) From X. Mi, P. Roushan, C. Quintana, et al., 2021, “Information Scrambling in Quantum Circuits,” Science 374(6574):1479–1483. Reprinted with permission from AAAS; (top right) Reprinted with permission from J. Shabani, M. Kjærgaard, H.J. Suominen, et al., 2016, “Two-Dimensional Epitaxial Superconductor-Semiconductor Heterostructures: A Platform for Topological Superconducting Networks,” Physical Review B 93(15):155402, http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.93.155402. Copyright (2016) by the American Physical Society; (bottom right) From B. Douçot and L.B. Ioffe, 2012, “Physical Implementation of Protected Qubits,” Reports on Progress in Physics 75(7):072001. © IOP Publishing. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved; (bottom center) R. Drost, T. Ojanen, A. Harju, and P. Liljeroth, 2017, “Topological States in Engineered Atomic Lattices,” Nature Physics 13(7):668–671, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4080, Springer Nature; (bottom left) From I. Butula and F. Nori, 2009, “Quantum Simulators,” Science 326(5949):108–111, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1177838. Reprinted with permission from AAAS; (center) Charlie Marcus, University of Washington, presentation to the committee, October 3, 2024, created by D. Sanchez.

logical materials, to create new sorts of topological superconductors. This is really a networked array of a coherent system,” she said.

The six topic areas in Figure 2-1 were meant as an example of the breadth of research being done in this area. A team of researchers has been examining the thermalization of entangled states (upper middle entry). They have been able to distinguish operator spreading and operator entanglement. “This is another system where … we can start thinking of what new physics and understanding we can gain out of them,” Mason said. Work from Matthew Fisher’s group at the University of California, Santa Barbara (upper left), has examined how measurements can affect entanglement and if it is possible to long-range entanglement even while something is being continuously measured. Complementary work has been done on quantum simulators (lower left). The other studies she mentioned were one in which engineered atomic lattices were created with atoms placed at different points in the lattice by a scanning tunneling microscope to induce topological states (bottom middle) and a theoretical exploration of the relationship between topologically protected states and entangled states (lower right).

These topic areas, however, would not cover all of the topics that would be touched on during the workshop, Mason said. Generally speaking, the workshop covered two broad categories of networks. The first was networks of coherent quantum systems at the small scale, from individual atoms to nanometer-scale clusters of atoms. The second was coherent quantum networks created from interconnections of active quantum devices that form nodes that are replicated to form a network at a large scale—spanning large distances that could cover a metropolitan area. Such large-scale networks could then again be replicated to form a network-of-networks easily spanning continental landmasses. The goal of the workshop, she said, would be to think as a group about the connections between these various areas and what sorts of research can be done with the new capabilities and understandings that are being developed.

With that, she offered a list of questions that the workshop organizers hoped would be considered at the meeting:

- What are the real open questions, problems, and applications that motivate us doing this, and which systems are the most promising?

- What can we learn from engineering quantum “active” matter about real, complex materials relevant to condensed matter, materials physics, and quantum information?

- What kinds of optimization or other problems can be mapped onto these networks?

- What are the organizing principles of quantum interactive dynamical phases?

- What kinds of equilibrium states can be implemented using measurement-based efficient approaches?

- What are the prospects for current and near-term experimental platforms that demonstrate interactive dynamics?

Finally, Mason offered two questions that can be asked of each of the systems under discussion. What are the connections and universal principles of engineered coherent matter and systems? and How can work on the various platforms help inform each other and employ applications? “It may be that someone has an idea about one platform that actually could be implemented better on a different platform,” she suggested. “Or it may be that understanding from one platform can inform understanding of another.”

With that in mind, she continued, the workshop organizers decided to structure the workshop so that there would be interaction among people discussing different platforms. To that end, there would be three sessions—on solid-state platforms, on atoms and platforms, and quantum information dynamics: natural and synthetic. The session on solid-state platforms would include talks on superconducting qubits and quantum simulation, nitrogen–vacancy centers, and defect candidates. The session on atoms and platforms would include talks on cavities, photonic networks, and atoms. The session on quantum information dynamics would include talks on monitored quantum circuits and synthetic topological systems. In each session, the presentations would be followed by a panel discussion.

In closing, Mason said that the planning committee intentionally did not include any talks specifically on quantum error correction. That was because it is such a big topic that it could serve as the topic of a workshop all by itself, she explained, although people were certainly welcome to offer their thoughts on it. Still, she concluded, the main goal of the workshop was to “think of different platforms and different ideas that use similar sorts of entangled states and coherent networks to access new physics and new ideas.”

COMPLEXITY AND QUANTUM-NESS

Workshop chair Marcus opened his presentation by saying that presenting the information in the workshop would be a challenge for two reasons. First, the planning committee decided that the presentations should be geared for people outside of the particular area—coherent quantum networks—being discussed. And second, the area itself is so broad that even people working in it are not familiar with everything going on in it. “I’m really here to learn,” he said, “and I think that the rest of my committee is also here to learn, because the field is that broad.”

As Mason had also done, Marcus offered an overview of the workshop, but he came at it from a different direction. He described scientific research in terms of factors—complexity and “quantum-ness”—and he illustrated that with a two-dimensional graph, with complexity plotted on the horizontal axis and quantum-

ness on the vertical axis. Even in cases where there is no quantum component, he said, great complexity can make research and understanding extremely difficult, and he offered the human brain as an example. Recent research in artificial intelligence is another example, he said. “We’re making headway in that direction, just along the horizontal axis.”

However, when one adds even the smallest amount of complexity to a quantum system, he continued, it is the sort of research issue that leads to Nobel Prizes. “Even just having two single quantum elements is already so hard that it took two generations of scientists before ideas became experiments,” he said. And the topics being covered in the workshop sit up in the upper right corner of that graph, where both complexity and quantum-ness are high.

The difficult issues in quantum mechanics arise not so much from the interference between quantum waves, which is a well understood phenomenon, Marcus said, but from the superposition of two or more quantum states. Even Bohr and Einstein, two of the early giants of quantum physics, were puzzled by how to think about superposition, Marcus noted. Nonetheless, he continued, the description of quantum mechanics in terms of superposition and probabilities is now “settled law.”

One of the most mind-boggling aspects of quantum mechanics is what Einstein referred to as “spooky action at a distance.” Marcus said, “We’re living in a world in which it appears that something akin to voodoo is really real. You really can stick a pin in a doll somewhere, and someone else, somewhere else, will say ouch, or maybe a better way to say it is the sticking of the pin and the shouting of the ouch will be correlated.” The fact that two actions can be correlated across a distance would seem to be quite unbelievable, he continued. “Yet, the correlation between the sticking of a pin in one location and the shouting of ouch in another location is a fact. If we have any facts in our world, that’s a fact.”

Furthermore, it is a remarkably useful fact, he said, because such correlations are at the heart of quantum computers, which have been shown to be able to do things that digital computers cannot. Although a digital computer was generally believed to be an efficient, universal computer, Peter Shor (1997) showed that this may not be true when quantum mechanics is taken into consideration. More recently, Leone and colleagues (2021) showed that if one wishes to model the quantum behavior of a system whose classical dynamics are chaotic, it is necessary to have a quantum computer. Thus, there are certain problems that need a quantum computer to solve, Marcus said, but it is not yet clear just how common such problems are.

Switching from quantum-ness to complexity, Marcus showed a diagram of a spin glass, which he called a “paradigm of complexity for a physicist.” One puts either classical dipoles (such as magnets) or quantum spins at various vertices in a lattice and asks what alignment they will settle into. Since magnets or spins placed near one another tend to align head to tail—with, in the case of magnets, the north pole on

one lining up with the south pole on the other—the multipole dipoles in the array will interact with one another. If there are just two magnets, or if multiple magnets are arranged in a straight line, it is easy to figure out their ultimate alignment. The dipoles will be alternating, pointing up, down, up, down, and so on. But in any more complicated arrangements, the dipoles will settle into some arrangement that balances the various forces among them. Figuring out exactly what that balanced alignment would be is sufficiently complex, Marcus said, that “if you try to make a computer algorithm to find out what direction all of those will spin, you’ll find yourself probably going down some long channel of options, making mistakes, and ending up in some metastable configuration, not the best possible arrangement.”

This sort of optimization problem, with trees of options and many possible wrong turns, has great technological relevance, Marcus said, because it arises in many areas, such as the problem of protein folding and determining the precise three-dimensional structure of a folded protein and knowing the sequence of amino acids that make up the protein. “These complex landscapes with lots of wrong turns are the generic working definition that I would like to present for complexity,” he said, noting the complexity is a sufficiently important problem that it was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2021. The three winners, he noted, were Giorgio Parisi, who wrote down the mathematics of how to deal with the sorts of valleys inside of valleys inside of valleys that appear in the complex landscapes when dealing with such problems as spin glasses, and two scientists, Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann, who worked on predicting climate change. The complexity of the environment does not necessarily involve quantum mechanics, he said, “but the complexity of the environment and the complexity of a simple system of spins pointing in different directions are two nice examples of the complexity of our world.”

Transitioning to networks, Marcus said that there are many different kinds of networks, each with its own flavor. In many respects, a tree network is the simplest because it has no loops in it, which means, among other things, that it cannot have the feedback interactions of the sort found in a spin glass. Lattice networks such as a square lattice or a Kagomé lattice both have loops, but those two types of lattice behave very differently when dipoles or spins are placed at the intersections, he said. Small-world networks characterize how a brain or the Internet is wired, consisting of clusters of tightly connected networks that are themselves connected by long “axons” or “Internet connections.” Another type is the random network, which might, for instance, reflect social connections in a population.

Finally, Marcus introduced the concept of frustration with the example of placing spins at the vertices of an equilateral triangle. If the rule is that each spin should point in a direction opposite to a neighboring spin, it is complicated to find a solution, he said. The first two spins placed at two vertices of the triangle will line up in opposite directions (up, down), but when a third spin is placed at the final vertex, its interaction with the existing spin that points up pushes the new

one to point down, while the interaction with the down-pointing spin pushes it to point up; thus, it is frustrated, with no orientation that allows it to do everything it “wants” to do. And, Marcus continued, if spins are placed on the vertices of a Kagomé lattice, the situation gets much more complicated.

With that background, Marcus then described some research he has done on complexity in quantum problems. He referred to a material that Mason had mentioned in her talk, an epitaxial, hetero-structured material grown with a semiconductor and a superconductor in epitaxial registry (Figure 2-1, upper right). It is a material that did not exist 10 years ago, and the invention of that material allowed a property of semiconductors, the ability to control conductivity with a voltage, and a property of superconductors, the ability to pass electricity with zero resistance, to coexist on the same wafer. And that combination allowed Marcus to study complexity that arises in quantum systems.

To do that, he used a device called a Josephson junction, which is made out of two superconductors separated by an insulating barrier. One interesting feature of a Josephson junction is its current–voltage characteristics. Unlike a resistor or capacitor or many other typical electronic components, the current–voltage relationship in a Josephson junction in nonlinear; the current depends on the sine of the phase difference across the insulator, while the voltage is proportional to the time derivative of the phase difference, so the current and voltage are related in a nonlinear way. Using such Josephson junctions, Marcus said, “enabled us to begin to fabricate the material systems that we’re studying in my laboratory that can be arbitrarily complex, while at the same time being something that can be fabricated in the laboratory rather easily.”

He then described the results of some work that has been done in his laboratory using arrays of Josephson junctions. In one case, for example, the researchers took measurements of the temperature at which such arrays globally lost their resistance to a current (i.e., became superconducting). The results showed that this critical temperature depended on an external magnetic field applied across the device; when the flux of the magnetic field passing through one of the squares of the array was zero or an integer multiple of a particular critical value, the critical temperature of the array reached a local maximum, or peak. There were also smaller peaks that appeared halfway between the larger peaks, still smaller ones halfway between those, and so on.

This problem had actually been solved mathematically in 1983 by Teitel and Jayaprakash, Marcus noted, and that paper showed where a superconducting vortex—which Marcus described as “a twist of the wave of the superconducting Josephson junction”—can be found in the array. “And from the 1980s until the 2000s,” he continued, “that became a more complicated and beautiful problem: where does the vortex live?” Recent work has shown that the patterns of vortices in the array of Josephson junctions will vary according to the applied magnetic field—specifically,

according to the magnetic flux going through a single cell of the array expressed as a fraction of a critical flux. For instance, Marcus said, when that fraction is ⅓, “the vortices like to stay away from each other, so they make these nice rows.” And at ½, the vortices make a simple checkerboard pattern.

The patterns get more complicated if one moves away from simple fractions. For instance, if one deviates from ½ by 2 percent, he said, “what you see is a crystallization of the defects. The defects themselves form a lattice.” Furthermore, he continued, “if I were to deviate in the next higher level of the hierarchy, you would see defects of the crystal of defects that would form.” This is an example of a behavior that rates high on both the complexity scale and the quantum-ness scale.

To sum up, he pointed to a review article that discussed how to make materials with certain band structures artificially and then see what sorts of structures they produce (Leykam et al. 2018). “One of the connecting points on our theme for today,” he said, “is the ability to build systems to specifically address questions and to complement the alternative approach to solid-state physics, which is to find rocks in the ground and see how they behave. We’ve now almost transcended the rocks-in-the-ground phase of solid-state physics, and now we’re building things to address specific questions.”

In closing, Marcus showed two papers that he said pointed to topics beyond his overview that would be addressed during the workshop. The first was a paper that discussed building quantum networks in which it would be possible to have multiple entangled objects (Alshowkan et al. 2021). Physicists have already built systems with a pair of entangled objects, he noted, “but now we need to build a network out of these things. We need to have all of these nodes all connected where there’s massive entanglement between all of them.” Building such a system will be a very hard problem, he predicted.

The second paper, published shortly before the workshop, which discussed a newly defined characteristic called “magic” (Niroula et al. 2024). Magic is the quantity that prevents one from classically computing a result, Marcus explained. “And now that there’s a way to quantify the non-classical computability of a system, we can now watch that quantity spread inside of an entangled network, and we can see what happens when the system is measured or communicated or spread.”

He ended by saying that life is getting very interesting now that information theory, materials science, solid-state physics, and quantum physics are all being merged into a challenge for this generation.

QUANTUM NETWORKS

Vedika Khemani of Stanford University offered yet another overview talk, this one focused on quantum networks and why they represent a new frontier for condensed matter physics.

Networks are ubiquitous, she said. Examples include satellites in space, people in a social network, or a graph showing the evolutionary connections among primate species. And the connections in a network can represent different things—ancestry and genetic closeness for the phylogenetic network of primates, for instance, or who is friends with whom in a social network. In short, one way to think about a network is that it is a system of interconnected elements representing the organization or flow of information, resources, or other entities.

Khemani then defined a quantum network as “a system of many strongly interacting quantum elements organized into different structures.” Much of condensed matter physics, she continued, can be thought of as a study of quantum networks, since all matter arises from interacting electrons self-assembling into some structure—atoms, molecules, crystals, glasses, topological insulators, superconductors, etc.—and condensed matter physicists seek to understand the different emergent structures (or networks) that the electrons organize themselves into.

About 20 years ago, she continued, there was a major conceptual shift in the field of condensed matter physics that has proved to be extremely powerful and extremely consequential. What happened is that researchers went from thinking about structures of phases in a more abstract, information theoretic way to characterizing ground-state phases of matter in terms of patterns of quantum information and quantum entanglement. And what they have come to appreciate, she said, is that graphical representations from quantum information theory, either unitary circuits or tensor networks, are very powerful for thinking about and understanding how entanglement is organized and how different phases can be distinguished by their entanglement structure. From this perspective, a quantum network can be thought of as a system of many strongly interacting quantum elements organized by the structure of quantum information.

This approach has really transformed condensed matter physics, Khemani said, particularly in bringing together the fields of many body physics and quantum information. “The reason we’re having this workshop today,” she continued, “is that all of us here believe that we are on the precipice of … another massive paradigm shift.” And this paradigm shift, instead of being driven by abstract theoretical ideas, is being driven by experimental breakthroughs in the ability to coherently and controllably assemble large, complex structures of many strongly interacting quantum elements.

A key feature of the engineered quantum networks that are being built today is that they allow researchers to control the interactions among the multiple quantum elements. Furthermore, researchers are thinking about the organization of these networks not just in terms of their structures or the patterns of quantum information that they represent, but in terms of the flow of quantum information through the network. “That is a big theme that I want to really emphasize here,” Khemani said. “We’re going to move from thinking about patterns of entanglement in static

equilibrium, low-temperature states, to thinking about networks characterized by the flow of quantum information through space-time, with intrinsically non-equilibrium dynamical quantities.”

With that, she modified her definition of a quantum network even further to be “a system of many strongly and controllably interacting quantum elements organized by the structure and flow of quantum information.”

Thinking in this way raises a host of fundamental questions, she said. First, how does an isolated quantum system reach thermal equilibrium under its own dynamics? This question dates back nearly to the dawn of quantum mechanics, but the new tools now available should reveal layers of new insight. Specifically, the question refers to coherent quantum systems, and the simplest way to make such a system coherent is to isolate it from its environment, so that it is not subject to environmental decoherence. But this means that there is no reservoir that the system is coupled to, which is the textbook approach to reaching thermal equilibrium. So, she asked, how does an isolated quantum system undergoing unitary evolution, which is perfectly reversible, reach thermal equilibrium, which should be a completely irreversible process under its own dynamics?

A second question is, Can a system evade thermal equilibrium? Can this thermalization process fail or at least be delayed for a very, very long time so that it seems as if the system does not thermalize on any timescale relevant to an experiment? “When thermalization fails, we are in totally new territory,” Khemani said. “All of our understanding of phases of matter is based on equilibrium statistical mechanics, so if we have systems that can be made to controllably evade thermal equilibrium, how should we think about phases of matter?”

This in turn leads to a third question, What intrinsically non-equilibrium phases of matter exist? This will require serious thinking and experimentation.

Fourth, How should a quantum network’s capacity to retain coherent quantum information be characterized? This may require moving beyond the usual types of order parameters thought about in condensed matter physics and bringing in concepts from quantum information theory. A network’s capacity to retain coherent quantum information is closely related to the threshold transition in quantum error correction “because there you imagine a system that’s subject to some kind of noise and the noise is trying to destroy quantum coherence,” Khemani said. “But is there some threshold? Is there a phase transition in how much noise is acceptable, how much noise can you tolerate while still retaining coherent quantum information?”

Additional questions include the following: How should the computational capacity of a quantum network be characterized? Is there magic in the network? Are there classes of states that can be used as a resource to perform quantum computation? “This is going to be a theme of this workshop,” she said, “which is really focused on the flow of quantum information through these different networks and in thinking about universal features that arise in the dynamics.”

The second big theme, she continued, is controllable interactions. The field is now moving into a really exciting domain where researchers are not limited to electrical charges interacting according to the laws that nature provides, but rather researchers can get the electrons to engage in completely different and new types of interactions that are allowed by the laws of quantum mechanics but that do not exist naturally in nature.

Khemani offered two examples of the sort of exotic phases that could be created experimentally now. The first was Kitaev’s toric code, which she described as a “paradigmatic example of an error correcting code.” In particular, she showed a model in two dimensions of a Z2 spin liquid. It is a solvable model and has been transformational in researchers’ understanding of Z2 spin liquids, she said. “And now, engineered quantum systems can build these types of interactions,” making it possible to experimentally probe quantum spin liquids.

The second example was the Haah cubic code for a model in three dimensions, which provides a different type of quantum error correcting code that is more robust than the toric code. “But it also has been really interesting for condensed matter physicists,” Khemani said, “because it gives you an exotic type of phase called a fracton phase.” Much rich physics has come out of studying phases like this, she said.

Khemani then briefly described some experimental work where researchers are able to control the interactions in a system. In the first, which was work coming out of the neutral atoms community, researchers were able to pick up individual atoms, move them in space, and get them to controllably interact with each other in groups (Bluvstein et al. 2022). “By doing this, a sequence of these types of moves,” she said, “you can really engineer all of these types of multi-body interactions that I was mentioning.”

A second example was work done using cavities (Kollár et al. 2019). “You can use cavity-mediated interactions to engineer geometries at will,” she said.

In a third example, from Monika Schleier-Smith’s group at Stanford University, the researchers worked with an array of atomic ensembles inside an optical cavity, with photons carrying information between atomic spins. The group was able to engineer a variety of effective geometries for the system (Periwal et al. 2021).

Putting it all together, Khemani said, “the new frontier from many-body physics is to think about these networks with controllable interactions.” They go beyond Euclidean lattices and simple two-body electromagnetic interactions. “And we ask, what are the types of equilibrium or non-equilibrium structures that we can get in these types of general engineered networks?” That, she said, would be the major theme of the workshop.

Having finished the major portion of her presentation, Khemani spent the rest of her presentation talking about some of the issues in the area that she finds particularly interesting and that would be touched on later in the workshop. She began

with universality in quantum dynamics. “If we have a generic, strongly interacting, isolated quantum system,” she said, “we expect this system to thermalize, which means that if you take a small subsystem in this strongly interacting system and you wait, that small subsystem at times looks like it’s reached some equilibrium state, and that equilibrium state … maximizes entropy subject to whatever constraints might exist in your problem.”

Generally speaking, she said, that end state is not particularly interesting. It is just some highly entangled state that is not very structured, so the entanglement is mostly useless. However, she continued, “there’s a lot of beautiful physics in understanding how the approach to thermal equilibrium happens.” How, for instance, does a system that is isolated get entangled? How do the different subsystems of a system get entangled in time? Are there universal features in the growth of that entanglement? How does quantum information scramble across the entire system? When subsystems come to thermal equilibrium, all information about the initial state is preserved for all times, but it can get very scrambled. What are the dynamics of this information scrambling? How can it be probed?

These questions have proved to be theoretically very rich, Khemani said, but what is really exciting is that along with researchers’ ability to generate controlled interactions in these systems, there also comes an ability to controllably probe these systems and to measure observables. “You can directly look at the dynamics of quantum entanglement,” she said. Something that would have been unthinkable even 10 years ago, and the ability to make these sorts of measurements is leading researchers to ask questions that would not have made sense to ask until a few years ago.

Moving one step further, Khemani asked how such systems can be prevented from reaching thermal equilibrium. She briefly described two approaches.

The first was many-body localization. “This is an approach where, by controllably engineering the types of disorder landscapes that a system moves in or the types of interactions that a system has, you can prevent the system for arbitrarily long times from reaching local thermal equilibrium,” she explained. This approach was used, for example, in an experiment by Immanuel Bloch’s group at the Max Planck Institute where they started with an atomic cloud whose atoms were all located in one half of an optical lattice and which never completely spread out over the lifetime of the experiment (Choi et al. 2016). “In this case, we prevented this growth of entropy,” Khemani said, and they did it by periodically driving the many-body localized system. With this approach, she said, it is possible to engineer “new kinds of out-of-equilibrium orders that wouldn’t have been possible in any equilibrium setting.”

The second way to keep such a system from reaching thermal equilibrium is by making controlled measurements. Usually, she said, people think of the environment making measurements on a system as something that leads to the destruction

of quantum coherence in that system. The environment making measurements acts as noise, and that noise will destroy coherence. But this can be counteracted by an experimentalist making controlled measurements in the system and using those measurements to provide feedback that removes the entropy generated by the environmental decoherence. “Measurements and feedback can suck entropy out of the system,” she explained, “while some unstructured measurements can add entropy, and the balance between these is at the heart of kind of active approaches for error correction.” This has led to a new approach in many-body physics where researchers, instead of treating measurements as probes, treating measurements as part of the many-body dynamics, which can have a dramatic effect on the state being measured. Measurements, she said, “can create, destroy, and restructure quantum correlations, and this can allow you to get new types of non-equilibrium phases driven by how these measurements are behaving.”

As a third example, she pointed to work from the Google Quantum AI group where they observed measurement-induced phase transitions in individual quantum trajectories labeled by controlled measurements. The work involved a new type of error-correcting code called the Hastings-Haah-Floquet code, generated by a periodic sequence of local measurements with some particular symmetries and structure.

Finally, she mentioned a theoretical breakthrough from 2 years ago—the discovery of good quantum low-density parity check (LDPC) codes. “This had been a holy grail, something that we’d been looking for in error correction for about 25 years,” she said. Since that discovery, her group has been thinking about the physics of these LDPC codes. “Every other phase of matter, or every other scheme of error correction corresponds to some non-trivial phase of matter,” she explained. The classical error correction used on magnetic hard drives, for instance, is related to the phenomena of spontaneous symmetry breaking for magnets. The toric code, which is the best error correcting quantum code that is currently known, is a model of Z2 topological order. It turns out, Khemani said, that LDPC codes are very complex and rich spin glasses—new types of spin glasses that have not been seen before.

DISCUSSION

For the discussion session following the presentations, Marcus and Khemani were joined by Pedram Roushan of Google, Charles Tahan of Microsoft, and Ana Maria Rey of JILA and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, who joined remotely. Mason served as moderator.

Mason began by asking the panelists how the quantum systems being discussed might be useful in materials science. “What sort of simulations can we do? Are there specific topics that are more relevant than others?”

Marcus answered that the field is entering an era in which researchers may understand enough to build materials unlike anything that nature has created.

The best analogy may be with the development of light-emitting diodes, which are objects that are not found in nature and which were designed deliberately to create materials with certain properties. When coherent quantum mechanical systems become many-body interacting systems, he said, it opens up an entire new vista in which human imagination can play.

Tahan offered a different sort of answer, noting that 20 years ago the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency started a project called Quantum Entanglement Science and Technology (QuEST) that examined, among other things, the issue of whether it was possible to create many-body states to solve optimization problems. “And none of that really worked because the systems were just not ready,” he said. “It took 20 years of developments to get to where we are now,” where such projects are becoming possible.

Khemani added that one way in which the current work on coherent quantum networks has relevance for real materials is through the back-and-forth between theory and experimentation. When physicists want to understand some very complex phenomena, they will often model it with some “toy system” that captures much of the physics. “The next step that’s now been really exciting,” she said, “is that we can actually probe these toy models in a laboratory setting because you can engineer these interactions.” As an example, she referred back to the spin glasses and LDPC codes that she had spoken about that were a model of error correction. “The people who wrote these models were not thinking about spin glasses,” she said. “But using tools from computer science that we use to study these codes, we can actually now say things about this new type of regime where you can get spin glasses,” which in turn are relevant to things that are seen in nature. “So I think that there is a very close kind of connection between all of these ideas and this flow of insights from one domain to the other,” she concluded.

Marcus briefly commented that the advances in the field have come about through a combination of government- and corporate-sponsored research, as reflected by the split on the panel between people from government agencies and those from corporations.

On a different topic, planning committee member Nicolas Peters said that two-qubit entanglement is a strong correlation between two particles, but when one looks at larger and larger systems, the entanglement is actually different and does not behave the same way that two-qubit entanglement does. “So when we start to do entanglement among multiple objects, we can’t convert between some of the forms of entanglement using local operations and classical communications,” he said. “What that means is we have to do something that’s a much more interesting and difficult operation in order to convert between the different types of entanglement,” and how one wishes to achieve quantum coherence among many different objects has some implications for how one would want to be able to shift around between the different types of entanglement.

Khemani added that it is not enough just to talk about how entangled a state is. The actual structure of entanglement matters. “An infinite temperature state is highly entangled,” she said, “but much of that is not useful. You can’t compute with it.” On the other hand, she continued, it is possible to have ground states that are topologically ordered and very entangled, which is a more structured and useful form of entanglement that can be exploited for computation.

Then Prineha Narang, University of California, Los Angeles, commented that how one optimizes and spreads entanglement over a larger network also depends on what one wants to do with the network. “That’s actually an interesting optimization problem in itself,” she said. “How smart do you want the end nodes to be, versus somewhere in the middle, which would be essentially asking, do you want to put quantum processors in every city, as opposed to in 10 cities?”

In response to an audience question about practical limits to scaling the sorts of coherent quantum networks being discussed, Marcus said that he has not been able to get the networks to work with high-temperature superconductors, so it is still necessary to cool the devices down to near absolute zero rather than to the 77 K of liquid nitrogen. This is a materials science problem, he said.

Tahan said that the refrigeration issue is not necessarily the biggest challenge to scaling up these devices. “We know how to build fridges,” he said. “So yes, there’s a question of, how big can it be built? Is it worth the cost? Stuff like that. But it doesn’t necessarily become the riskiest thing in terms of a scalable system.”

Marcus added that there is also a cultural hurdle because there is often a disconnect between how physics and materials science approach the world. “It’s hard to find people working on exactly that problem,” he said. There are people working on high-temperature superconductors, and there are people working on qubits, and they are each interested in their own issues.

Next, Rey triggered an extended discussion by asking about the quantum-ness of the materials and systems being discussed. Certainly quantum behavior can be observed in experiments with maybe 10 or 20 particles, she said, “but otherwise, I don’t think we have actual probes of entanglement.” So, she asked, “when is really entanglement coming into a play to describe a material?” In the case of macroscopic systems, she questioned to what extent entanglement has actually been observed and what role entanglement plays in describing a property of a material.

At this point, Matteo Ippoliti, University of Texas at Austin, mentioned measurements of the quantum Fisher information (QFI) of a material as good evidence of entanglement in materials, but Rey responded by questioning whether current measurements are really genuine measurements of QFI or are actually measurements of some proxy of QFI. Narang agreed that there are currently very few techniques to actually measure QFI in materials. Khemani noted that measurements of entanglement have been made in systems of up to 70 qubits, but Rey responded that this is still a small system.

Rey elaborated on her point by saying that if, for example, she wanted to understand high-temperature superconductivity or some other phenomenon that is really at the frontier, how big a role would genuine entanglement really play? Or to what extent is entanglement a key feature in a phase transition? “I’m not saying that these systems are not quantum,” she said, but how important is this quantum-ness once one starts to go to a more macroscopic level?

Eun-ah Kim, Cornell University, commented that it is important to distinguish between quantum-ness and entanglement. “When you have just a pure state, you have only entanglement to think about,” she said. “But a lot of the times in macroscopic systems, we a have mixed state. Even simulators are in an obviously mixed state, but they are close enough to pure state. So we think about pure state, and the only thing we’ve got is entanglement.” But what is really interesting, Kim continued, is how one bridges between pure states, which are the starting points of simulators, and dynamics and quantum fluctuation in macroscopic systems, which are in mixed states.

Marcus spoke of the example of superconductors and Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer theory. It is a mean field theory, so the entanglement is hidden, but that is different from saying the entanglement is absent, he said. The Cooper pairs that carry a superconducting current are clearly entangled, and, indeed, the entire Fermi sea of electrons in a conductor is a massively entangled system.

Of course these things are entangled, Rey answered, “but what I’m talking about are the tools that we need to model their behavior.” Superconductors are modeled with a mean field theory that can be solved in a very simple computer. So while entanglement is at the heart of individual properties, she is interested in to what extent entanglement is a key factor in modeling and understanding the properties of materials and which properties require taking entanglement into account for their explanation.

REFERENCES

Alshowkan, M., B.P. Williams, P.G. Evans, N.S.V. Rao, E.M. Simmerman, H.-H. Lu, N.B. Lingaraju, et al. 2021. “Reconfigurable Quantum Local Area Network Over Deployed Fiber.” PRX Quantum 2:040304.

Bluvstein, D., H. Levine, G. Semeghini, T.T. Wang, S. Ebadi, M. Kalinowski, A. Keesling, N. Maskara, H. Pichler, M. Greiner, V. Vuletić, and M.D. Lukin. 2022. “A Quantum Processor Based on Coherent Transport of Entangled Atom Arrays.” Nature 604:451–456.

Choi, J.Y., S. Hild, J. Zeiher, P. Schauß, A. Rubio-Abadal, T. Yefsah, V. Khemani, D.A. Huse, I. Bloch, and C. Gross. 2016. “Exploring the Many-Body Localization Transition in Two Dimensions.” Science 352(6293):1547–1552.

Kollár, A.J., M. Fitzpatrick, and A.A. Houck. 2019. “Hyperbolic Lattices in Circuit Quantum Electrodynamics.” Nature 571:45–50.

Leone, L., S.F.E. Oliviero, Y. Zhou, and A. Hamma. 2021. “Quantum Chaos Is Quantum.” Quantum 5:453.

Lesser, O., A. Stern, and Y. Oreg. 2024. “Josephson Junction Arrays as a Platform for Topological Phases of Matter.” Physical Review B 109(14):144519.

Leykam, D., A. Andreanov, and S. Flach. 2018. “Artificial Flat Band Systems: From Lattice Models to Experiments.” Advances in Physics: X 3(1):14730552.

Niroula, P., C.D. White, Q. Wang, S. Johri, D. Zhu, C. Monroe, C. Noel, and M.J. Gullans. 2024. “Phase Transition in Magic with Random Quantum Circuits.” Nature Physics 20:1786–1792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-024-02637-3.

Periwal, A., E.S. Cooper, P. Kunkel, J.F. Wienand, E.J. Davis, and M. Schleier-Smith. 2021. “Programmable Interactions and Emergent Geometry in an Array of Atom Clouds.” Nature 600:630–635.

Shor, P. 1997. “Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Prime Factorization and Discrete Logarithms on a Quantum Computer.” SIAM Journal on Computing 26(5):1484–1509.

Teitel, S., and C. Jayaprakash. 1983. “Josephson-Junction Arrays in Transverse Magnetic Fields.” Physical Review Letters 51(21):1999–2002.