Transporting Freight in Emergencies: A Guide on Special Permits and Weight Requirements (2024)

Chapter: 2 Special Permitting for Overweight Divisible Loads in Emergencies and Disasters

CHAPTER 2

Special Permitting for Overweight Divisible Loads in Emergencies and Disasters

Introduction

Emergency and disaster declarations can cause confusion in the freight community because such declarations may rely on different elements of law that define emergency and disaster differently. More specifically, special permitting for overweight divisible loads during disasters includes two different elements of federal law, though only one applies broadly to all states.

Further, while federal law applying to emergencies and disasters affects overweight special permitting for divisible loads and state-issued permitting on the Interstate Highway System, states can also issue special permits for overweight loads on a state level according to state law. State-level declarations can only apply to state roads. In both cases, federal and state, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations (FMCSR) may allow states to waive elements of the law related to hours of service.

Federal- and state-level disaster declarations for special permitting may also include FMCSR waivers in the same declaration. This fact, along with the differing state-level laws for special permits, emergency and disaster definitions and authorities, and an overlay of interstate and federal rules and regulations, can cause confusion for carriers, CMV enforcement officers, and state permitting offices when these different conditions come into effect in an emergency or disaster.

This chapter attempts to define these matters as they apply to overweight special permitting of divisible loads in emergencies and disasters, with the note that at a state, tribal, or territorial level, the specifics may vary significantly according to the laws governing that nonfederal jurisdiction. Consequently, this guide groups states into two general groups—permissive and restrictive—recognizing that these groupings both constitute a wide range of individual circumstances.

Understanding Legal Citations

Because this chapter refers to laws, codes, regulations, and guidance, a quick explanation may assist readers in understanding the way these elements of the law relate to one another. When Congress or a state passes a law [public law (PL) at the federal level], that law adds to, deletes, or amends the state’s code of laws [United States Code (USC) at the federal level]. Often these laws, as implemented in the code, grant authority to a federal or state agency or department to issue regulations according to an established process defined in some other element of the federal or state code. When these agencies or departments issue regulations, they become part of the federal or state regulations [U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) at the federal level] and carry the weight of the law that authorized the agency or department to issue them.

This guide, when referring to codes or regulations, will use the common legal citation method of title, source, chapter, or section when identifying specific elements of the law. Such citations typically leave out the chapter or subchapter of the citation since sections of the law and regulations are numbered sequentially across the entire title. For example, 23 USC 127 refers to a specific part of the U.S. Code, Title 23, Section 127, titled “Vehicle weight limitations—Interstate System.” Congress amended this section of the USC many times over the years since it first established this section of the code in PL 85-767 in 1958, the last time in PL 117-58 in 2021. 23 USC 127 (i) refers to a specific part of Section 127 of 23 USC, in this case, “Special Permits During Periods of National Emergency.”

Similarly, Title 23 of the U.S. CFR, “Highways,” in Chapter I, Subchapter G, Part 657, cited as 23 CFR 657, implements federal vehicle size and weight limits on the Interstate Highway System. Finally, legal citations may use the Latin abbreviation “et seq.,” which means “and what follows,” when citing a section of the law that covers multiple subsections. For example, a citation that reads “23 CFR 657 et seq.,” refers to the entirety of Part 657 of 23 CFR.

Federal Emergency and Disaster Declaration Legal Framework

23 USC 127(i) requires a presidential declaration under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 USC 5121 et seq.) (also referred to as the Stafford Act) before states may issue special permits to overweight vehicles for divisible loads. When PL 112-141, the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act, added the language for 23 USC 127 to the USC, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) issued implementation guidance for states. This guidance explicitly stated the three conditions necessary for states to issue special permits under 23 USC 127 (i):

- The president has declared a major disaster under the Stafford Act;

- The permits are issued in accordance with state law; and

- The permits are issued exclusively to vehicles and loads that are delivering relief supplies.

However, the preceding section of the law, 23 USC 127 (h), which applies only to fuel shipments between Augusta and Bangor, Maine, on Interstate 95 for use by the Air National Guard base at Bangor, requires only a “national emergency.” 23 USC 127 (h) thus refers to emergency powers in the USC under Title 10, as regulated by the National Emergency Act (50 USC 1601 et seq.), not the Stafford Act (42 USC 5121 et seq.). Thus, outside of this one specific circumstance in Maine, no other national emergency declaration for any purpose can affect overweight special permitting for divisible loads on the Interstate Highway System—only a Stafford Act declaration under 42 USC 5121 can do that.

The Disaster Relief Act of 1974 and the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act of 1988 that amended the 1974 law define an emergency as the following:

Any occasion or instance for which, in the determination of the President, federal assistance is needed to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe in any part of the United States.

That definition is the only one that applies to Stafford Act declarations.

There is a separate and different definition related to the FMCSR that regulates hours of operation. This emergency definition, contained at 49 CFR 390.5, states the following:

Emergency means any hurricane, tornado, storm (e.g., thunderstorm, snowstorm, ice storm, blizzard, sandstorm, etc.), high water, wind-driven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, mud slide, drought, forest fire, explosion, blackout, or another occurrence, natural or man-made, which interrupts the delivery of essential services (such as electricity, medical care, sewer, water, telecommunications, and

telecommunication transmissions) or essential supplies (such as food and fuel) or otherwise immediately threatens human life or public welfare, provided such hurricane, tornado, or other event results in: (1) A declaration of an emergency by the President of the United States, the Governor of a State, or their authorized representatives having authority to declare emergencies; by Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA); or by other Federal, State, or local government officials having authority to declare emergencies; or (2) A request by a police officer for tow trucks to move wrecked or disabled motor vehicles.

Further, 49 CFR 390.5 defines several other emergency conditions and emergency relief:

Emergency condition requiring immediate response means any condition that, if left unattended, is reasonably likely to result in immediate serious bodily harm, death, or substantial damage to property. In the case of transportation of propane winter heating fuel, such conditions shall include (but are not limited to) the detection of gas odor, the activation of carbon monoxide alarms, the detection of carbon monoxide poisoning, and any real or suspected damage to a propane gas system following a severe storm or flooding. An “emergency condition requiring immediate response” does not include requests to refill empty gas tanks. In the case of a pipeline emergency, such conditions include (but are not limited to) indication of an abnormal pressure event, leak, release, or rupture.

Emergency relief means an operation in which a motor carrier or driver of a commercial motor vehicle is providing direct assistance to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives or property or to protect public health and safety because of an emergency as defined in this section.

Confusion arises in the freight community because state and federal emergency declarations affecting overweight vehicle special permits may refer to the special permitting process under 23 USC 127(i) and the FMCSR waivers in the same declarations, but they are unrelated in how they define emergency and how states and the federal government implement them.

At the state level, the declaration of a state emergency or disaster is more varied. States codified elements of the Stafford Act to qualify for federal assistance in disasters, thus establishing a state system of disaster declaration. Governors and state legislatures also possess widely divergent emergency powers under their state’s constitution and laws. The form and limits of these powers vary significantly from state to state.

For example, some states grant broad emergency authority to governors with little or no legislative oversight. A few states reserve emergency powers to the state legislature. Therefore, the state powers available to some governors at the state level may be broader than those available to the president at the federal level, while in other states, the governor may possess limited or proscribed emergency powers.

Likewise, disaster and emergency declarations can overlap and relate to one another. For example, following a hurricane, a state may (1) request a federal disaster declaration under the Stafford Act; (2) issue a declaration waiving hours of service under the FMCSR for drivers delivering emergency relief supplies, while also establishing special permits for overweight divisible loads under 23 USC 127; (3) declare a state emergency under state law and deploy the National Guard to prevent looting in damaged areas; and (4) request that federal troops assist with restoring order in an area with rioting under elements of the Insurrection Act (PL 9-39, implemented in various parts of the USC). Another subsequent weather disaster could happen within days or weeks, affecting some but not all of the same geography.

Likewise, as the COVID-19 pandemic showed, the same event or incident can have a public health emergency that is covered under different laws and codes than the Stafford Act, presidential and state disaster declarations defined under the Stafford Act, and state and federal emergency powers under the law related to insurrections and martial law invoked by the president, governors, Congress, or state legislatures. In each case, the authority cited for the declaration, the powers invoked, and the role played by federal and state agencies will vary depending on the circumstances.

Only a Stafford Act major disaster declaration by the president (as defined in 42 USC 5121 et seq.) brings the authority of 23 USC 127 (i) into effect. This is the only condition under which states may issue special permits for overweight divisible loads on the Interstate Highway System.

However, for the purposes of special permitting on the Interstate Highway System, only a 42 USC 5121 et seq. Stafford Act disaster declaration by the president brings the authority of 23 USC 127 (i) into effect, authorizing states to issue special permits for overweight divisible loads on the Interstate Highway System.

State Disaster and Emergency Declarations

Stafford Act disaster declarations are the system by which local communities, counties and parishes, states, and the federal government respond to disasters, natural and man-made. Because of their frequency of use, Stafford Act declarations and disaster authority are a well-established and practiced process across the United States, and presidential declarations occur under every presidential administration and have done so since the Stafford Act’s inception. This system of disaster declaration is the one most associated with natural disasters in the United States, even though its authority extends to other kinds of disasters.

Federal Stafford Disaster Declarations

The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 USC 5121 et seq.), signed into law on November 23, 1988 (PL 100-707), established the present statutory authority for federal disaster responses. Each state within the United States has implemented some aspect of the federal law into state law, thus creating a system across states of requesting a declaration between county or parish and the governor, like the system the Stafford Act implemented between governors and the president. At the federal level, disaster response generally falls under the authority and responsibility of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), part of the Department of Homeland Security since 2002.

When a state requests a federal disaster declaration through FEMA, the president can then declare a federal disaster. In a known, impending disaster (e.g., a hurricane), a state can preemptively declare an emergency or disaster and apply for federal assistance. In addition to aid from federal agencies to a state or local government, a disaster or emergency declaration allows for the reimbursement of some state and local expenditures in responding to the disaster through programs administered by FEMA. In significant disasters, Congress may authorize additional funding and create special relief programs, as it did after Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy or during the COVID-19 pandemic.

State Disaster Declarations

Although the system varies in each state, in the event of a disaster that overwhelms the ability of a local jurisdiction (e.g., town, city, county, parish) to respond with local response assets or those provided through mutual aid, a jurisdiction lead executive (e.g., mayor or county official) may request aid from the governor, who can declare a county- or parish-level or state-level disaster.

Under provisions of the Stafford Act, governors can then make a request from the federal government for assistance if the disaster exceeds the ability of the state to respond. Not all emergencies or disasters rise to the level of presidential declarations. Some emergencies or disasters may apply only at a local jurisdiction or state level. While these incidents do not meet the requirements necessary for the special permitting of overweight vehicles under federal statutes, they may meet the requirements for FMCSR relief in some cases, which affects more than just overweight vehicles with divisible loads. FMCSR relief is not part of the overweight special permitting process.

Additionally, different states have different laws governing what constitutes an emergency or disaster and different processes and procedures for implementing OS/OW permitting within the state, on state roads, to respond to that emergency or disaster. Thus, some states may declare an emergency or disaster through the governor, a state legislature, or another public official. This state declaration, which may specify specific routes, then implements overweight special permitting on state roads to address the emergency or disaster. For example, a governor may declare an emergency due to a fuel shortage or an untimely harvest, permitting overweight divisible loads to obtain special permits (with or without obtaining FMCSR relief).

Generally, in a state-only emergency or disaster (without a presidential Stafford Act disaster declaration), states may issue special permits for overweight divisible loads only for state roads not part of the Interstate Highway System under the specific provisions of their state law governing such circumstances.

The important distinction is that a state-level declaration affects only state roads not defined as part of the Interstate Highway System as defined in the USC. Further, the Interstate Highway System includes more than just interstate highways, and several specific routes on the Interstate Highway System in certain states have clauses set in law that allow for OS/OW vehicles to exceed federal restrictions, addressed in 23 USC 127 (j) to (q), (u), and (w).

Divisible versus Nondivisible Loads

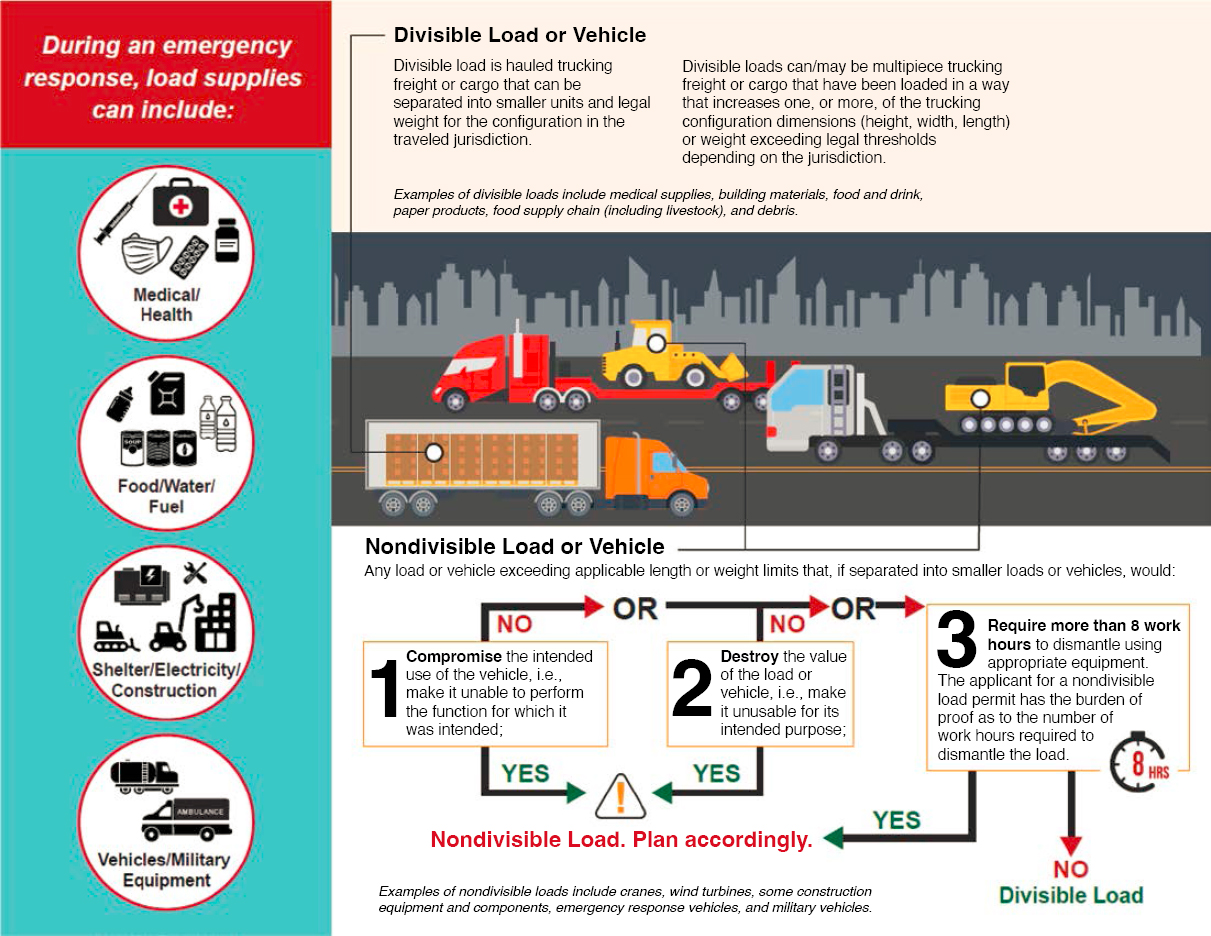

Divisible load definitions and interpretations about divisible loads can vary by state. One way to define divisible loads is by defining what they are not—that is, by defining nondivisible loads.

FHWA defines nondivisible loads as “any load or vehicle exceeding applicable length or weight limits which, if separated into smaller loads would: (i) compromise the intended use of the vehicle (i.e., make it unable to perform the function for which it was intended); (ii) destroy the value of the load or vehicle (i.e., make it unusable for its intended purpose); or (iii) require more than eight work hours to dismantle using appropriate equipment” (2024a).

Thus, a divisible load is anything other than a load defined by FHWA as nondivisible, since a shipper could otherwise divide, dismantle, or separate the load in less than 8 work hours so as not to exceed width, length, or weight limits.

Some confusion in the freight community may still exist regarding the nondivisible load definition. FHWA issued a clarification in 2018 noting, “the word ‘or’ at the end of (ii) means that a load that meets any one or more of the three definitions shall be considered nondivisible. States are required to use the federal definition only when considering whether to issue a nondivisible load permit allowing an overweight vehicle or load to operation on the Interstate System and roads providing reasonable access to and from the Interstate” (Heavy Duty Trucking 2018).

In practice, many states in the past tended to focus on the third part of the FHWA definition (the 8-work-hour standard), particularly as it related to counterweights or other items that take less than 8 hours to remove. However, FHWA noted, “loads may still be defined as nondivisible if the removal of the objects will make the load unable to perform the function . . . and/or unusable for which it was intended” (Heavy Duty Trucking 2018). This clarification notes the conditions of the first part of the FHWA definition. As such, a nondivisible load is one that meets any one of the three parts of the FHWA definition (see Figure 1).

In practice, however, for most emergency supplies shipped during disasters under divisible load special permits, the loads are often readily divisible (e.g., loads of lumber, pallets of bottled water). In any case, under special permitting, only divisible loads qualify, and any nondivisible loads require a regular permit through the normal process administered by the state (the same is true of oversize loads).

Additionally, several state-only emergency declarations in the past related to fuel shortages may affect FMCSR-related relief more than overweight special permitting. Hazardous materials shipments have load-specific safety requirements not related to weight but to headspace left in tanks to allow for expansion or off-gassing to prevent leaks or incidents. No regulation relieves carriers of these safety parameters. Thus, while there are some hazardous materials that could be shipped in overweight situations because of their specific gravity being the determining factor, the determining factor may relate more often to tank capacity and safety parameters for shipment rather than the weight of the liquid or gas in the tank, given that shippers already have an economic incentive to maximize the amount shipped within safety parameters under normal conditions.

Exemptions to Federal Weight Limits Not Requiring Special Permits

In addition to the specific state-level or road segment exemptions in 23 USC 127 (e) to (g), (j) to (q), (u), and (w), 23 USC 127 (s) contains an overweight exemption for Natural Gas and Electric Battery Vehicles: “A vehicle, if operated by an engine fueled primarily by natural gas or

powered primarily by means of electric battery power, may exceed the weight limit on the power unit by up to 2,000 pounds (up to a maximum gross vehicle weight of 82,000 pounds) under this section.” Some states have the authority to issue permits under grandfather clauses, such as found in 23 CFR 658 Appendix C.

More significant for emergencies, 23 USC 127 (r) contains overweight exemptions for emergency vehicles that never require an overweight permit under the following conditions:

(r) Emergency Vehicles.—

- In general.—Notwithstanding subsection (a), a State shall not enforce against an emergency vehicle a vehicle weight limit (up to a maximum gross vehicle weight of 86,000 pounds) of less than—

- 24,000 pounds on a single steering axle;

- 33,500 pounds on a single drive axle;

- 62,000 pounds on a tandem axle; or

- 52,000 pounds on a tandem rear drive steer axle.

- Emergency vehicle defined.—In this subsection, the term “emergency vehicle” means a vehicle designed to be used under emergency conditions—

- to transport personnel and equipment; and

- to support the suppression of fires and mitigation of other hazardous situations.

State Systems of Special Permitting for Overweight Divisible Loads

State permit-issuing offices for OS/OW permits have unique state legal and regulatory requirements for OS/OW permits, operations, and what constitutes OS/OW within their state. Special permitting implemented under 23 USC 127 (i) or state-road-only emergency or disaster special permitting can equally vary from state to state and on tribal land or in U.S. territories.

The processes and structures by which state offices issue overweight permits can vary substantially (for example, state DOTs issue the permits in some states, while other states may issue them through the highway patrol or department of motor vehicles). In addition, special permitting for overweight divisible loads is optional. For a complete list of state permit-issuing offices, with contact details provided, see Appendix A of this guide.

While a presidential declaration allows for states to implement special permitting, they must actively do so through a state-level declaration. Further, despite the variations between states in who issues the permits, the requirements for permit holders while operating, and how the state issues OS/OW permits, there are two general models in use in the United States for implementing overweight special permitting for divisible loads—permissive or restrictive (see Figure 2). This categorization serves the purpose of enhancing a high-level understanding of approaches undertaken at the state level.

Permissive Special Permitting

The permissive special permitting model prioritizes efficiency and urgency of delivery over enforcement and roadway damage prevention. States adopting this model use one of two general systems to issue special permits. Some permissive states issue a blanket special permit for overweight divisible loads in emergencies that carriers can obtain at any time, with or without an emergency declaration, which becomes effective during the emergency when paired with the state-level emergency declaration implementing special permitting under 23 USC 127 (i) or state law (for state-only emergencies or disasters). Other states include provisions in state law or regulation that declares that a copy of the state-level emergency overweight special permitting declaration is the permit during the period of emergency.

Permissive states do not usually restrict special permit loads to specific routes or designate specific commodities allowed for special permits. These states largely leave routing up to the carrier and enforcement decisions to individual CMV enforcement officers. States may advise CMV operators to consult routing assistance tools to help avoid load-restricted infrastructures. While this system has the advantage of speeding up the delivery of essential goods in a disaster or emergency, it may increase roadway damage and lead to bad actors attempting to use the special permitting process for goods or loads not needed or destined for disaster areas.

Restrictive Special Permitting

The restrictive special permitting process balances efficiency and urgency with enforcement and roadway protection. These approaches vary more in their implementation than do permissive states but share some commonalities. The most restrictive states issue special permits through their normal permitting process, with the only difference being that they allow permits for carriers exceeding weight limits for divisible loads of emergency supplies.

Restrictive states may also specify the emergency commodities allowed to obtain special permits or restrict special permitted loads to specific routes or destinations. Less restrictive states may not define the commodities or limit loads to certain routes or destinations, or they might implement an expedited permitting process for emergency loads or issue more generalized permits than they would otherwise.

Special Permit Validity

Several key questions related to permit validity and enforcement arise during special permitting. Permissive states issuing blanket permits that become valid with a disaster declaration can create confusion among some carriers, especially those not accustomed to shipping overweight loads. The period of permit validity is the period of the emergency in the declaration. For presidential declarations this is usually 120 days, unless extended by another declaration, which would also need to accompany the permit. For state-only emergency or disaster declarations the period is often 120 days, and, like federal permits, they may require renewal beyond that date through additional declarations. However, the specific period of the emergency for special permitting is defined by state law and regulation and the language contained within the state declaration.

Some enforcement officers reported using the Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance (CVSA) portal to check permit validity. State permitting offices should encourage and work with state and local law enforcement to disseminate information and produce training that law enforcement agencies can implement to increase this practice more widely. The second question regarding permit validity relates to interstate movements of goods under another state’s special permit. For more on the ways to coordinate interstate movements under special permitting please see Part II of this guide.

Interstate Movement Under State-Only Declarations

For state-only declarations, interstate permit recognition occurs through MOUs before the disaster or emergency or via coordination during the emergency or disaster response and recovery. While most state-only emergencies and disasters do not impact interstate movements, there are situations where interstate travel may be an issue. For example, two neighboring states declaring untimely harvests may wish to coordinate their special permitting.

Several options exist for such coordination. Neighboring states may wish to enter a mutual aid compact via an organization like regional American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) mechanisms, or they can incorporate their coordinating and mutual aid mechanisms for special permitting into existing emergency management MOUs that exist between states.

Interstate Movements Under Presidential Disaster Declarations

For interstate movements under presidential disaster declarations that activate the provisions of 23 USC 127 (i), interstate coordination can be essential to speeding critical supplies into a disaster area. There is no federal requirement for states to recognize OW divisible load permits outside the state issuing the disaster declaration that implements special permitting. Therefore, permits, even those issued under 23 USC 127 (i), require shippers to obtain regular or special permits from every state they pass through en route to the disaster area. This could potentially impact disaster response for some shipments and slow the arrival of associated supplies.

Consequently, interstate coordination of overweight special permits for divisible loads and logistical planning for disasters and emergencies are essential to a speedy and effective response. Interstate coordination can occur through two mechanisms or some combination of the two. The first mechanism is the same as that for state-only emergencies. As noted above, states may wish to coordinate declarations, prepare MOUs, implement regional compacts, or include special permitting in existing emergency management mutual aid agreements.

The second mechanism shifts the coordination to shippers, carriers, and emergency management. Essentially, shippers and carriers coordinate and ship to logistics hubs or sites with pre-positioned stockpiles, where regular shipments of material (not overweight) may collect inside the declared disaster state or near it, for transfer to other vehicles that can ship overweight divisible loads within that state under that state’s special permitting system. Federal, state, and local emergency management can assist in coordinating, establishing, and managing such hubs and should include such planning in the transportation emergency support function annexes of their state and local emergency operations plans. State permitting offices can and should assist state emergency management in this planning as it relates to their role and functions.

This page intentionally left blank.