Toward a New Era of Data Sharing: Summary of the US-UK Scientific Forum on Researcher Access to Data (2024)

Chapter: 4 Data for Net Zero, Biodiversity, and Climate Adaptation

4 | DATA FOR NET ZERO, BIODIVERSITY, AND CLIMATE ADAPTATION

ENVIRONMENTAL DATA, whether focused on climate, severe weather events, biodiversity loss, or air pollution, represent “both the challenge and the opportunity that we have in grappling with questions of researcher access to data,” observed Gina Neff, professor and executive director of the Minderoo Centre for Technology and Democracy at the University of Cambridge, who filled in for Marian Scott, professor of environmental statistics at the University of Glasgow, in introducing the third panel at the forum.

On the one hand, we have wicked hard problems to solve in terms of meeting climate goals and mitigating climate disaster. On the other hand, there are real challenges involved in terms of ever-increasing computer power and the energy and resources that it takes to make science. What are we, individually and collectively, doing to think through some of our own practices? How can we think through the data challenges that will help contribute to getting to net zero and other goals?

Neff summarized the framing that Scott, who was unable to attend the forum, planned for the beginning of the session. As observations of the world become increasingly extensive and voluminous through digital technologies, researchers need to think in terms of systems, she said. Some of the issues involved in systems thinking include the following:

- Technical:

- Integration of data across misaligned spatiotemporal resolutions and from different domains

- Data fusion—qualitative and quantitative data structures

- Assimilation of real-time data

- Operational and Societal:

- Data silos and ownership, to allow discovery

- Privacy and commercial aspects

- Security

The nature and diversity of environmental data mean that new ways must be found to link them, which is complicated by the different structures of data sources, Neff observed. Nevertheless, data fusion of related datasets provides complementary views of the same phenomenon and allows more accurate inferences than a single dataset can yield. This is both technically and organizationally challenging and involves the social sciences as well as the natural sciences.

Neff particularly emphasized the concept of a digital Earth, “an interactive digital replica of the entire planet that can facilitate a shared understanding of the multiple relationships between the physical and natural environments and society.” Creation of a digital Earth involves data from an evolving set of data streams, models, and other sources, including citizen science. It combines qualitative and quantitative methods and data, deals with issues of scale and scaling, and leverages new types of data and sources. “This gives us a model of what’s possible when we bring new types of data together and what the opportunities are around the kinds of conversations that we’re having in this room.”

The Environmental Costs of Data

The environmental consequences of gathering, analyzing, storing, and sharing data are “striking,” said Loïc Lannelongue, research associate in biomedical data science and green computing at the University of Cambridge. The global greenhouse gas emissions of data centers are an estimated 100 megatons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year, which is about the same as the emissions of U.S. commercial aviation. Storing a terabyte of data consumes about 10 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent annually. Transferring data uses about 0.006 kilowatt-hours per gigabit. A genome-wide association study of 1,000 traits in UK Biobank can generate up to 17 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent—which is about the same as 350 passengers flying from London to Paris—and a large language model like ChatGPT can create 550 tons, without taking into account the large-scale deployment of its latest versions. Furthermore, none of these numbers counts the energy and materials that go into manufacturing the electronics for these activities. “We’re talking about very large numbers,” said Lannelongue. “It doesn’t mean that all computing has this kind of impact or that we need to be paranoid about every keystroke. But because some analyses have such large impacts, and because we’re discussing large amounts of data today, it’s important to think about consequences for the environment.”

To address these issues, Lannelongue and his colleagues have created the Green Algorithms project to promote environmentally sustainable computational science. It provides tools to calculate carbon footprints. It also was the basis for a deep dive into bioinformatics, resulting in guidelines to make computing more environmentally sustainable. Among the guidelines developed by the Green Algorithms project are the following:

- Keep, repair, and reuse hardware and equipment.

- Promote efficient data centers.

- Estimate and report footprints for projects and include this in cost-benefit analyses.

- Carefully choose computing facilities.

- Optimize or use optimized code and software.

- Account for sustainability in hardware renewing policies.1

Recently, the group has brought in stakeholders from computational biology to create GREENER, a set of principles designed to make environmental sustainability a core element of computational research. The principles are organized around governance, responsibility, estimation, energy and embodied impacts, new collaborations, education, and research.2 In the area of responsibility, for example, the principle reads as follows: “Embracing both individual and institutional responsibility regarding the environmental impacts of research. This involves being

___________________

1 Lannelongue, L., J. Grealey, A. Bateman, and M. Inouye. 2021. Ten simple rules to make your computing more environmentally sustainable. PLoS Computational Biology 17(9):e1009324.

2 Lannelongue, L., H.-E.G. Aronson, A. Bateman, et al. 2023. GREENER principles for environmentally sustainable computational science. Nature Computational Science 3:514–521.

transparent about these and initiating bold initiatives to reduce them.” Achieving this and the other principles requires both bottom-up grassroots movements and top-down approaches, said Lannelongue, “because there’s only so much postdocs and PhD students can do.” Funding bodies and heads of institutions must be involved both to generate the data on environmental impacts and to act on those data.

The next goal is an institutional dashboard to monitor and reduce carbon footprints from computing across research groups, units, and departments. A longer-term goal is the development of standards to certify research groups that achieve sustainability—for example, by moving a compute to regions where more renewable energy is available or performing a compute when less polluting energy can be used. Progress requires educating people and doing more research to understand, for example, exactly how computers use power and how their power use can be made more efficient.

Lannelongue concluded with a quotation from the Royal Society’s 2020 report Digital Technology and the Planet: Harnessing Computing to Achieve Net Zero. “Digital technologies developed and deployed in pursuit of net zero must be energy-proportionate—i.e., they must bring environmental or societal benefits that outweigh their own emissions.”3

From Tools to Trust

CarbonPlan uses the best available science to increase the use of climate solutions that work and decrease the use of ones that do not work, said the organization’s executive director Jeremy Freeman. Based on his experience at CarbonPlan, Freeman discussed two similarities and one major difference between his current field and the one in which he used to work—computational biology and neuroscience.

The first similarity is that the data tools available to both fields work well. “I’m not sure I would have said that 10 years ago, [but] I definitely feel that now.” Though many fields of research have to work with very large datasets, the number of people who deal with such data on a day-to-day basis is actually fairly small. The vast majority of research is focused on information that has been extracted from data. Furthermore, as large datasets grow, people have become adept at developing tools to deal with those data.

The second similarity is that “speed really matters” in both fields. For example, the rapid dissemination of data and preprints during the COVID-19 pandemic fostered public conversation and maintained focus on ongoing issues. With climate change, though the basic facts have been known for decades, new information needs to be disseminated rapidly to inform time-sensitive decisions. When the Inflation Reduction Act was being debated in the U.S. Congress, for example, researchers were doing rapid modeling of individual proposals to predict the implications of those provisions for greenhouse gas emissions. “The biggest challenge there,” said Freeman, “is how to do research that is fast but also rigorous, and where we can be confident in what we’re saying and hold ourselves to a very high bar but also get the information out as fast as possible.”

The major difference between the two fields, Freeman said, is the absence of regulation around climate issues. In biomedical science, an extensive regulatory apparatus surrounds the roles of data and science in informing public decision making. With climate change, such a regulatory apparatus is “basically nonexistent.” Government agencies generate data and support work on climate models, but the use of data to inform decisions about such topics as risk management or insurance is vanishingly scarce. For example, the provision of offsets to compensate for the carbon emissions from flying or having something delivered is totally unregulated. “Those claims might be true, [or] they might be false; you have no idea.”

Another example Freeman cited involves risk maps for wildfires. The state of Oregon supported an initiative to build a new fire map to document the risk of wildfire across the state, but the map was withdrawn from public

___________________

3 The Royal Society. 2020. Digital technology and the planet: Harnessing computing to achieve net zero. London: The Royal Society.

access when people objected to how high the risk was in their locations. Meanwhile, the insurers in the state have access to very similar data, which they have been using to increase insurance rates or not offer fire insurance at all. “It’s a major disconnect around the role of data in public decision making around climate change.”

Trust in science and the scientific process is essential for science to inform public policy and public decision making, Freeman concluded. “It matters in biology. It matters in climate change. We have to trust each other as scientists, and the public has to trust science. That’s a big challenge for all of us.”

Grounding Indigenous Rights in Biodiversity Data

Indigenous Peoples represent about 5 percent of the global population, but they steward about 20 percent of the total land base and 80 percent of global biodiversity, observed Lydia Jennings, a presidential postdoctoral fellow at Arizona State University and a research fellow at Duke University. Furthermore, contemporary stewardship practices encompass not only ecological data but also Traditional Ecological Knowledge; geospatial data; and air, soil, and water quality data. Environmental data must “embrace the stewardship that Indigenous Peoples clearly have but also support their data needs,” Jennings said.

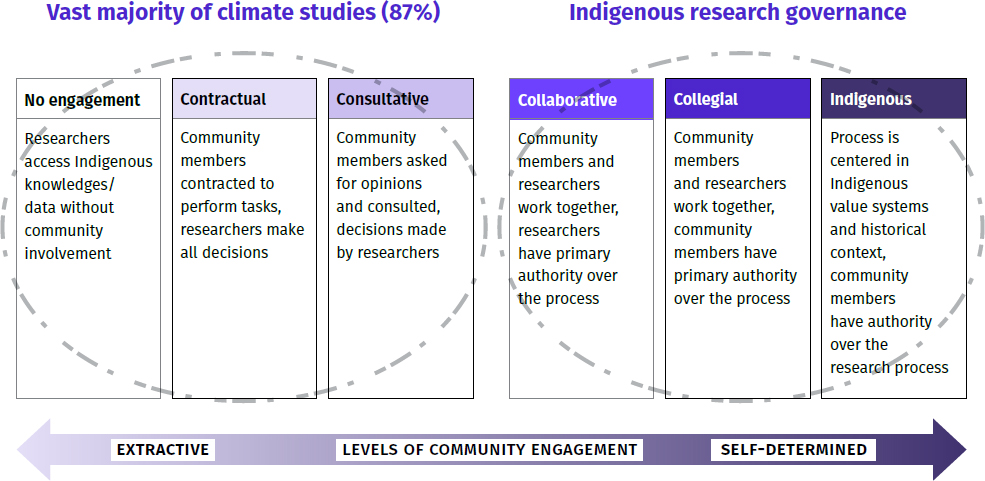

A study of engagement with Indigenous Peoples from 20 years of climate studies found that about 87 percent of studies were working in an extractive capacity or had minimal consultation with Indigenous groups, said Jennings (see Figure 4-1). Meanwhile, many Indigenous communities do not have a data scientist, access to data, or even connections to the internet. “How truth-grounded is the data that we generate around climate studies,” asked Jennings, “without involving the expertise of Indigenous Peoples?”

SOURCE: David-Chavez, D. 2022. Testimony Before the United States House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space, and Technology Hearing on “Now or Never: The Urgent Need for Ambitious Climate Action.” https://static1.squarespace.com/static/618d2a970c299b1a94c7d5ed/t/62bcafcf3e31910c9da3b2f2/1656532944074/chavez_testimony.pdf.

Jennings presented a set of principles for Indigenous data governance, known as the CARE principles, developed by a coalition of Indigenous scholars.4

- Collective Benefit—Data ecosystems shall be designed and function in ways that enable Indigenous Peoples to derive benefit from the data.

- Authority to Control—Indigenous Peoples’ rights and interests in Indigenous data must be recognized and their authority to control such data respected.

- Responsibility—Those working with Indigenous data have a responsibility to share how those data are used to support Indigenous Peoples’ self-determination and collective benefit.

- Ethics—Indigenous Peoples’ rights and well-being should be the primary concern at all stages of the data life cycle and across the data ecosystem.

By bringing a focus on people and purpose to data governance, the CARE principles are complementary to the FAIR principles that data should be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable, Jennings said. “We think about how the FAIR and CARE principles go hand in hand, with data being as open as possible but as closed as necessary to support the needs of Indigenous communities.”

Major challenges arise in data governance for Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples largely are not the legal rights holders of their data, even as more researchers than ever are collecting data from and with Indigenous communities. Huge amounts of data reside in archives, museums, repositories, and online databases collected from colonial expeditions, and in many cases Indigenous communities are not even aware of what data exist, much less how they should steward and govern those data. Information about community names, provenance, and data protocols is missing from collections. Issues of responsibility and ownership surround environmental data, and metadata are often missing, incomplete, or marked by racist terminology.

Jennings discussed several solutions to these challenges. Indigenous intellectual property can be recognized through authorship and attribution. “Who are the community members who are contributing to the data? How are they involved in the entire life cycle of the research process?” Metadata can be enriched using local context tags derived from community use. Data use and reuse should be tracked to see who is accessing data and how those data are being used. Data review committees can apply the CARE principles to specific data repositories. Data access and sharing protocols between Indigenous Peoples and other data actors can provide Indigenous Peoples with governance authority so that the data are grounded in the truth and expertise of the communities from which they came, ensuring more accurate and ethical data to address biodiversity and ecological challenges. “We all have a role within these data life cycles,” she said. “Whether you’re a community, an individual researcher, a data repository, or a funder, all of us have a role to support ethical Indigenous data governance practices.”

In response to a question about the CARE principles, Jennings observed that the principles were created to uphold Indigenous sovereignty, but “what has been really fascinating within this work has been how many people from other marginalized communities are coming forward and saying, ‘The CARE principles are some of the only data principles that bring back the people relationships to data.’” Perhaps with some modifications, she said, they could be applied to other populations, such as Black communities in the United States and other groups that want to share their data while protecting their rights.

Jennings also pointed out, later in the forum, that just as Indigenous communities think about the implications of decisions seven generations into the future, data scientists need to think beyond their own careers to the needs and data responsibilities of future generations.

___________________

4 Jennings, L., T. Anderson, A. Martinez, et al. 2023. Applying the “CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance” to ecology and biodiversity research. Nature Ecology and Evolution 7(10):1547–1551.

Involving Communities

Following the presentations, moderator Neff asked the panelists about the best ways to encourage communities of researchers to adopt different ways of thinking about responsible data collection, use, and participation. Jennings responded that researchers need more engagement with the communities on the ground. As an environmental scientist, she said, she is in favor of using data from Indigenous sources. “But as an Indigenous person, I think a lot about our rights and the issues with having all of our data open.” Processes are needed that not only generate benefits but also share those benefits with communities from which the data are derived. “Otherwise, we’re going to continue to have a slowed-down process in the long term and potentially not hav[e] information.”

Freeman agreed that communities are not centered enough in working with data. This can result, for example, in harm to communities by climate initiatives designed to achieve some sort of collective benefit. Transparency and accountability can help ensure that such initiatives serve broader ends while not directly damaging communities.

Lannelongue emphasized the importance of cost-benefit analysis but with broader definitions of both costs and benefits. A benefit to groundbreaking research might be making the same research available more quickly. Costs can be not only environmental harms but also harms incurred by Indigenous Peoples and local communities involved in research.

An incentive to incorporate community perspectives is to require that authors from affected communities be included in published papers, said Jennings. Researchers could also be encouraged strongly or required to have training in ethical practices, with such training starting early in a person’s career and with support from funding agencies. “During my undergraduate and graduate school years, these aspects of ethics as they apply to ecological scholarship were not on the radar, really, until 2020. Then a lot of us started to question how [we were] engaging in ecological research that does cause harm to the stewards of the lands.”

Acting on Data

The discussion also turned to incentives and disincentives to act on estimates of the environmental costs of data collection and analysis. Simply increasing awareness of the carbon footprint of various actions can be a powerful incentive, said Lannelongue. Similarly, acknowledgment in a paper of the energy used in achieving a result can motivate conservation among others.

Freeman added that incentives to reduce energy usage have proven much more effective and acceptable in the United States than disincentives. “Taking away people’s perceived personal freedoms, especially in this country, is incredibly hard to do.”

Breakout Group Questions

What are the challenges in bringing together (fusing/integrating) environmental datasets, and how can we move forward?

- Federated data may be a more appropriate term than integrated data, since the diversity of datasets makes integration at scale very difficult. Federation requires developing common languages, common tools, and common understanding of purpose, not just in the environmental sciences but also in any research discipline.

- Different communities have evolved different standards, practices, and data cultures. For communities to collaborate and provide each other with a system of checks and balances, they must share not only their data but also their challenges, such as reducing their carbon footprints.

- Cultural differences between nations and parts of nations can influence responses to the use of environmental data.

- Data are much more densely connected and available in some parts of the world than in others, which can create biases in models used to predict the future.

- Representation matters in the use of facial recognition data, to take just one example. More generally, combining datasets can pose the risk of privacy challenges and a misalignment of purposes. Clarity about those purposes—and a resolve to do no harm—can help avoid problems.

- Unlike many scientific data, the data needed to assess progress toward net zero often are not shared. Defining net zero as a shared problem would allow different communities to learn from each other and shape the culture of individual disciplines. There is also a business case for sharing these data, because validation for progress can provide companies with a competitive advantage.

- Getting products into the market can be an incentive for speed in data gathering and analyses, in contrast to publishing an academic paper.

- A federal agency could be in charge of developing and interconnecting datasets from both public and private sources.

How can we frame these challenges in systems thinking, especially as we would also wish to consider the interconnections (known and unknown)?

- Combining datasets implies interconnectedness, which requires systems thinking. If oceanography has implications for climate and climate has implications for food security, these fields, and many more, are all interconnected. A shift toward systems thinking will be required to bring these fields together.

- Systems thinking needs to extend from the modeling of individual assets to the modeling of entire systems.

- Because not everyone has the same capabilities and backgrounds, tiered systems should be available for using data at different levels and in different ways.

- In addition to CARE and FAIR, the concept of TRUST—transparency, responsibility, user focus, sustainability, and technology—is an important and valuable perspective.

Environmental data may be open or protected, and we may wish to link them to health and economic data. How do we overcome the challenges of linking such data sources?

- Bringing people together across disciplines is required to tie economic data to environmental data to health data to other forms of data.

- Linking natural world impacts with economics is difficult but necessary when adding social behaviors into the modeling of climate impacts. Expertise from sources like Wall Street, for example, can provide data on the operations of financial systems.

- The basic understanding that someone’s metadata may be someone else’s core data provides an impetus to share data. With data that need privacy protections, making metadata available can create an implementation-level alignment for later sharing of data, even though some asymmetries are likely to remain.

- Ensuring long-term investments in data stewardship and sustainability is a major challenge. With some exceptions, the missions of federal and non-federal funders tend not to cover indefinite commitments to repositories and data management. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration is an exception, in part because the data the agency has collected are expensive and cannot be replaced.

- Data are embedded in computational and analytical infrastructures, including the software that supports query, correlation, and analysis, and this infrastructure also needs long-term support.

- The loss of expertise in data annotation and curation can cause difficulties in data stewardship. That is why metadata and annotation need to be done at the birth of the data, not after the fact.

- Building tools, such as big data visualization tools, helps create the infrastructure for data stewardship. These tools can also help communities that may not have the capacity to access and use data themselves.

- Applying the movement toward modularity and abstraction that has characterized software systems in recent decades to data infrastructure would help make data stewardship sustainable over the long term.

- Long-term stewardship requires a diversity of funding streams so that stewardship does not depend on any one organization.