Toward a New Era of Data Sharing: Summary of the US-UK Scientific Forum on Researcher Access to Data (2024)

Chapter: 3 Accessing and Sharing Health Data

3 | ACCESSING AND SHARING HEALTH DATA

THE SECOND PANEL of the forum explored approaches to health data collection, access, and sharing. Health data encompass information about people’s behaviors and locations, phenotypes and genotypes, medical histories, and responses to clinical trials. Whether gleaned from mobile apps or patient records, insights from health data are critical for advancing biomedical research.

However, accessing, processing, and sharing health data also entail major legal, ethical, and technical challenges. The panel’s presentations and the subsequent discussion addressed key issues around sensitive health data and data governance and how these can be addressed to improve future health research, including research in crises. The panel examined how health data access and use are managed in different contexts, how trusted research environments work, and how public trust can be fostered to increase the sharing of sensitive health data.

Data Sharing During the COVID-19 Pandemic

As examples of the benefits of sharing, and hazards created by withholding, health data, Michael Worobey, professor and head of the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Arizona, described the critical role health data played in understanding and responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. On December 30, 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission in China released a confidential urgent notice to hospitals that “the Huanan Seafood Market in our city has successively witnessed patients suffering from pneumonia of unknown cause. In order to effectively respond to the situation, every medical institution must thoroughly investigate and provide the statistics of patients suffering from pneumonia of unknown cause and exhibiting similar characteristics that you have treated in the past week.” Within 11 minutes of its release, the notice was leaked and spread throughout Chinese social media. Later that day, a free email service, which had previously spotted outbreaks of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, the Zika virus, and the Ebola virus, broke the news to the wider world. Five days after that, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the outbreak of what would become known as COVID-19 was underway.

On January 10, 2021, a consortium led by Professor Yong-Zhen Zhang of Fudan University publicly shared the genome sequence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which “became immediately the blueprint for the Moderna vaccine,” said Worobey. However, the first genome had actually been sequenced 2 weeks earlier, on December 27, and Chinese authorities at the national level, like the then–Director General of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, did not learn of the outbreak—let alone this sequence—until days later. Even municipal and provincial public health authorities did not grasp that an important new outbreak was underway until December 29, 2019.1 In early January 2020, the national government blocked the sharing of SARS-CoV-2 genome data, with this embargo broken on January 10 by Zhang’s team.

___________________

1 Worobey, M. 2021. Dissecting the early COVID-19 cases in Wuhan. Science 374(6572):1202–1204.

More than a year later, in March 2021, a joint WHO–China study was released. Case data in that report revealed not only that many of the early cases were linked to the Huanan Seafood Market but also that cases not linked directly to the market were among people who lived near the market.2 More recently, on April 5, 2023, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention published a paper on the genetic evidence of wild and illegal animals at the market and shared the data in public Chinese sequence data repositories. That followed a preprint (i.e., not peer reviewed) of the same study, released about 1 year earlier, which did not mention animals and implied that species other than humans were not a source of the virus. An earlier WHO–China joint report from 2021 similarly stated, “No verified reports of live mammals being sold around 2019 were found.”

“The genetic data published this year tell a very different story than what the same folks were saying a couple of years ago,” Worobey observed. In fact, the genetic data in the 2023 report were actually produced in January and February of 2020, “so it took 3 years for these data to be shared.” In the meantime, said Worobey, “the world became convinced that this virus emerged from a lab.” According to a poll by The Economist/YouGov, two-thirds of U.S. adults said in 2023 that it is definitely or probably true that the COVID-19 virus originated from a lab in China, up from about half in 2020.3 “We’ve taken our eye off the real threat, which is the interface between wildlife that carry these viruses and humans in big cities.” If the data had been shared more recently, Worobey said, “this pattern would have looked very different.”

Using Health Data While Protecting Privacy

OpenSAFELY is a secure platform for analyzing the primary care records collated, updated, and used by general practitioners in the United Kingdom’s National Health Service. But “that’s underselling what it is we have,” said Pete Stokes, director of platform development at the University of Oxford’s Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science. The electronic health records (EHRs) in OpenSAFELY have data for 58 million people, which is more than 99 percent of the population of England. The data include detailed information on all general practitioner contacts and some information about nearly all health issues dating back to birth. The data are updated in real time by general practitioners, so they are never more than 10 days out of date. “There’s huge power in these data,” said Stokes.

Until a few years ago, the results made possible by OpenSAFELY were not available because of the challenges posed by working with health data. Working with hugely detailed EHR datasets is slow and difficult, and needless duplication of effort is common. EHRs contain confidential medical information, and access raises privacy concerns. Patients, professional groups, and campaigners want robust public transparency around what is done with records when access is granted. And code typically is not shared among groups, which hinders quality assurance, review, reuse, and the development of trust.

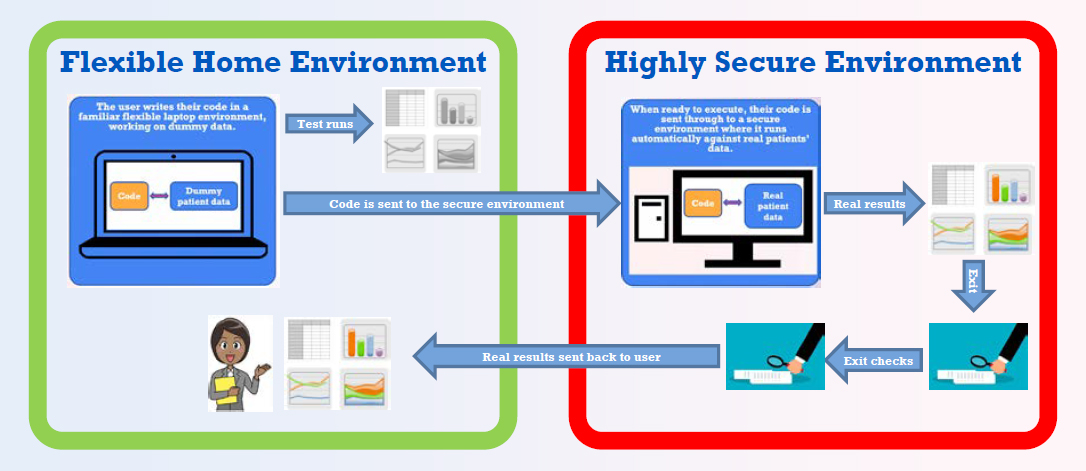

OpenSAFELY overcomes these problems through a new approach to data analysis. Rather than downloading data to a laptop or working on pseudonymized or de-identified data in a trusted research environment, OpenSAFELY is a set of software tools that can be combined to form a platform built on top of any database. In effect, it turns the database into a trusted research environment at the source of the data rather than in a remote location. “Rather than bringing the data to us, we take the software to the data.” Researchers receive structurally correct synthetic data against which they write their code (see Figure 3-1). They then submit their code to be run with real patient data in a secure environment. The results are checked by members of the OpenSAFELY team to ensure that those outputs do not jeopardize patient confidentiality. Then the researchers receive the results.

___________________

2 Worobey, M., J.I. Levy, L. Malpica Serrano, et al. 2022. The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was the early epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. Science 377(6609):951–959.

3 Sanders, L., and K. Frankovic. 2023. Two-thirds of Americans believe that the COVID-19 virus originated from a lab in China. YouGov, March 10. https://today.yougov.com/politics/articles/45389-americans-believe-covid-origin-lab.

SOURCE: Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science.

Besides solving security problems, this system has other benefits, Stokes said. Because users do not write their code inside a secure environment, they can share the code and results more easily. The site has public logs that show who is running code at any given time along with the details of their projects. “Everything is transparent, which helps build public trust and ensure proper and ethical use of data.” Federated analytics also have benefits; medical records are stored by two different companies in the United Kingdom, and the code can be run against each of the datasets and the results compared. Researchers can work more quickly, improving their productivity, and they can adopt and modify code that has been used previously. “If you want to do some analysis of asthma, for example, you can see who has already done analysis on asthma, how [they have] curated the data, [and] how [they have] selected their sample of people.”

As of the date of the forum, more than 150 projects from 22 organizations had made use of these data, even though OpenSAFELY has not yet publicized the tool. Meanwhile, every user contributes code and knowledge to a growing open stack of knowledge. OpenSAFELY has received strong formal letters of support from governmental and nongovernmental organizations, including several citizen juries.

In response to a question, Stokes elaborated on the process of generating synthetic data against which to test code. The first step in generating such data is defining the characteristics of the people in a sample. The synthetic data then incorporate those categories, making it easier to write and test code. “It doesn’t slow [researchers] down,” said Stokes, “because it’s not that different from running your code on real data.” Researchers like this approach, he added, because they can generate results much faster than they can using other approaches.

Lessons from Analyses of Epidemics

When working with health data, different countries deal with the issue of privacy in different ways, observed Christl Donnelly, professor of applied statistics at the University of Oxford. In the United States, under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), data are anonymized or de-identified by removing identifying data from a record, including names, addresses, and social security numbers, said Donnelly. However, it has

been shown that people can be re-identified by combining the remaining data with other types of available data. As a result, below a lower limit of the number of people who appear similar in a database, those data cannot be published.

In the United Kingdom, data are protected under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which specifies that data cannot be made available in datasets if those data can be re-identified by any means reasonably likely to be used. This is an interesting distinction, said Donnelly, because “what’s reasonable to one person may not be reasonable to another depending on how dedicated you are. Also, what may be reasonably easy or reasonably difficult to do now may not be so difficult in [the] future.”

Responding to epidemics is in everyone’s interest, but sensitivities nevertheless arise. With the first epidemic of SARS, the Hong Kong police were involved in analyzing data on contacts between people who had been exposed to the virus, said Donnelly. Also, in epidemics in general, some of the key data require individuals to be identifiable in order to make links—for example, in contact tracing. The West African Ebola epidemic from 2013 to 2016 was an example of an epidemic that prompted ongoing public debates about the ethical, practical, and scientific implications of wide data access.

Policy questions and data needs can change across the different phases of an epidemic. Also, many data sources may be available to answer the many questions that exist. For example, monitoring of wastewater to detect ongoing levels of disease can provide fully anonymized data, Donnelly observed, since sewer systems tend to serve large groups. The combination of epidemiologic data with measures of mobility among populations can provide very useful information.

WHO has published five data principles to guide its actions:

- WHO shall treat data as a public good.

- WHO shall uphold Member States’ trust in data.

- WHO shall support Member States’ data and health information systems capacity.

- WHO shall be a responsible data manager and steward.

- WHO shall strive to fill public health data gaps.

Application of these principles can help in the sharing of data needed to understand epidemics, but there can also be disincentives to data sharing, Donnelly observed. For example, data comparing outcomes among hospitals may disincentivize the sharing of data if a hospital feels that its reputation will be harmed by the release of such data.

Responsible Stewardship of Data

A question was asked during the discussion period about who has the responsibility for stewarding data and how that stewardship should be accomplished, especially given cases where data were available but then were withdrawn. Stokes noted in response that one depository for genomes is privately owned and that the owner of the repository could “just turn off the switch, and all of that disappears. That seems a tremendous vulnerability.” Besides establishing websites that mirror data, Donnelly urged that a mechanism be established for explaining why data were removed from public access, whether for correction or some other reason.

Stokes also observed that single answers about stewardship are not possible, in part because different groups have different interests in data availability. A better option than designating a single group as a gatekeeper would be principles that govern stewardship. In that way, organizations specifically interested in enabling research would be responsible for data stewardship while providing access to anyone with a good research question.

Ensuring Adequate Privacy

Issues of stewardship also arise in protecting the privacy of people with health information in a database. Standards regarding the amount of privacy needed vary by the type of data being considered, from the medical records gathered by health care providers to sample survey data to other types of data, and deciding on the level of protection needed is “very difficult,” said Stokes. For example, the GDPR requires that privacy protections make it not reasonably likely that someone could re-identify a person from the available data, but there is no empirical test of this standard. “You will know when you have it wrong because someone will break it.” People have to err on the side of caution while making judgments about what is necessary, he said.

A related issue is how long data must be kept private—in other words, when do they become the “patrimony of humanity”? When people die, they stop having the same privacy protections in law, Stokes responded, “but that doesn’t mean you want to make [the data] freely available.” In the United Kingdom, for instance, census data are released after 100 years. This question will come up with increasing frequency as more historically important datasets become available, Stokes predicted. It also may need to be revisited in light of data that have implications for someone’s children or grandchildren.

COVID-19 as an Impetus for Change

Finally, a question was asked about how the COVID-19 pandemic changed the ways in which data are handled. Donnelly emphasized the importance of “not just doing the right thing but [also] being seen to do the right thing.” Data privacy systems need to build trust so that people are willing to participate in the systems established to respond to a pandemic. One way Donnelly has done this in her work has been to involve advisory panels that include not just academics but also community members who can see and understand the processes involved in gathering and protecting data and provide input to these processes.

Stokes agreed, pointing out that the law in the United Kingdom gives authorities the right to release some kinds of data if they judge that such a release would serve the public interest. In addition, emergency legislation during the pandemic made some forms of data available, though these provisions have expired, and data protections have moved to a different legal basis. Nevertheless, Stokes concluded, during the COVID-19 pandemic “we made, worldwide, huge advances in the access to data, the timeliness of access to data, and the timeliness of publishing research. Those are legacy gains that came from a terrible situation that we need to collectively bank and not go back to where we were.”

Breakout Group Questions

Are de-identified health data the “patrimony of humanity”? If so, when does this happen?

- The terms “de-identified,” “standards,” and “health data” can each have different definitions. The last term, for example, could refer specifically to a designated record set held by a covered entity in the United States, or it could be the broader set of health-related data generated from someone’s browser history or social media interactions. The definitions used affect what people might consider to be the patrimony of humanity, which may mean that the data are available to all for use in any way that they are needed.

- Though some data clearly qualify as health data, ambiguities surround classifying other kinds of data as health data, such as societal or environmental factors that impact health.

- Making de-identified data widely available may benefit a community while having quite different impacts on individuals. People within a community may have different levels of vulnerability to discrimination.

- Protections may vary between countries. People may give consent for the use of data without realizing that the data may be used for sensitive purposes, that new purposes may be developed, or that the data may be used by industry and academia.

- Individuals can provide consent for themselves but not for their entire communities, which can create conflicts between reconciling the rights of the individual and the community with potential benefits to society.

- Different kinds of data have different standards for their release, from 100 years for census data to 50 years postmortem for data under HIPAA to no time under the common rule that governs human subjects’ protections.

- Social norms change over time, and what may be acceptable or unacceptable to people today could be different in the future, which complicates decisions about when potentially sensitive data should be made available.

Are common standards needed for sharing health data?

- While common standards upon which everyone agreed would be desirable, various complications can make this goal ethically difficult to achieve. For example, the significance of race and ethnicity can vary by context, people can be more or less sensitive about particular kinds of data, contested boundaries in data definitions can be difficult to establish, and the existence of incentives in such areas as diagnosis reimbursement models can make standards difficult to transfer from one context to another.

- Common standards do exist in some fields, but they may be based on only some populations, such as North American or European populations, and may not apply in the same way to other populations.

- A challenge for the use of data is to document the context in which data are gathered and used. Collaboration with local researchers is one way to provide context, but bringing in representatives of communities, such as Indigenous populations, may be necessary as well.

- Without common standards, researchers need to be careful to define terms and make their research transparent so that people can interpret and replicate results accurately and in the appropriate context.

- A complication with setting standards is that data can be generated by entities not involved directly in research, and the resulting data may not lend themselves easily to research. Standards may be needed upstream of research to influence how those data are being generated.

- Standards predicated on reducing the risk to individuals to zero can be too strict. A better approach would be to balance and minimize the risks without compromising the ability of the data to be used, for example, in responding effectively to a pandemic.

- The goals to be achieved through common standards can motivate and guide their creation.

Is there a moral and ethical imperative for sharing health data?

- Making de-identified health data available generally serves a public good, which creates a moral imperative to do so, but this imperative has limits. Broad consent to use data may later result in sensitive uses that were not envisioned. People differ in their perceptions of how industry and academia will use data, and the line between these two can be blurred in practice. One possibility is that a company could go bankrupt and void the contracts and accompanying protections on the data to which it has access.

- Most people do want to share their data because they recognize a societal benefit, but they also want their data to be used appropriately for public benefits and in a way that is not detrimental to them personally if

- the data were identified. This also creates an imperative to use data responsibly and rapidly and to ensure that they are protected.

- Pre-existing policy frameworks, the existence of standard operating procedures and institutional experience, the adaptability of infrastructure, and access to cross-disciplinary expertise can help in making decisions about whether data should be made available in times of crisis.

- Defining a patient’s rights in legislation is more practical than relying on ethical arguments that may prove difficult to enforce.

- Retaining the trust of the public is imperative.