A Roadmap for Disclosure Avoidance in the Survey of Income and Program Participation (2024)

Chapter: 9 Maintaining Usability While Preserving Confidentiality: Potential Strategies

9

Maintaining Usability While Preserving Confidentiality: Potential Strategies

In Chapters 4 to 8 the panel discussed several alternative methods for increasing privacy protection and reducing disclosure risk. In this chapter the panel explores how adoption of these methods might affect the usability of Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data and how reductions in usability could be mitigated through the provision of multitiered modes of access. The panel also explores more open two-way communications about data privacy and access between SIPP users and the Census Bureau. Finally, the panel discusses Title 13 and how its interpretation may be modernized to improve data access and usability.

As the Census Bureau evaluates potential privacy solutions and develops new modes of access to SIPP data, it will be important to evaluate those solutions in terms of their potential impact on the three dimensions of usability discussed in Chapter 4: accuracy, feasibility, and accessibility. Detailed discussions about various privacy protection methods are provided in the other chapters.

This chapter uses the following five potential modes of access as illustrations, arrayed here from the most to the least accessible:

- Online tabular/analysis builder, a tool for online analysis of SIPP data, particularly for tabular outputs and statistical analyses, with limits on the outputs that can be generated (i.e., no minimums, maximums) and differential privacy protections applied to the results (see Chapter 7).

- Public-use microdata, a publicly available microdata file that includes a limited number of variables, possibly along with synthesized

- variables for information that is too disclosive to release (see Chapters 2 and 3).

- Synthetic data, a synthesized dataset with a gold standard verification or validation server (see Chapter 6).

- Secure online data access (SODA), a secure virtual environment where approved users can access stand-alone SIPP data and obtain results following data disclosure review or infused with noise and correct inferences, but with lower start-up costs than when working through a Federal Statistical Research Data Center (FSRDC; see Chapter 5).

- FSRDCs, the secure labs already in place, at which SIPP and administrative record linkages are available to users holding Special Sworn Status and who have approved proposals. Users may need to work in the lab rather than remotely if they are working with tax or other administrative data.

Now consider each dimension of usability in greater detail with illustrative examples of how they may be assessed across different modes of access.

ACCURACY

As introduced in Chapter 4, the core element of the most traditional, but also the narrowest, definition of usability—often called validity and sometimes called accuracy—builds on basic concepts of statistics. A statistic is any function of a set of observations from a dataset. Some statistics are simple, such as a mean, a variance, a correlation coefficient, or cells in a contingency table. But others are not so simple, such as the coefficients on variables included in a linear regression estimated by ordinary least squares. Yet others may be even more complex, such as the parameters in a generalized or nonlinear model, or the parameters in a sophisticated causal-effects design using propensity scoring, instrumental variable, or other methods. A statistic may be computed from a cross-sectional dataset, like one wave of SIPP, or from multiple waves, as would be the case if the statistic measured income mobility over time, for example.

Two important dimensions of the accuracy of a statistic from a particular dataset are unbiasedness and consistency, on the one hand, and reliability in terms of confidence intervals, on the other. Unbiasedness and consistency are related concepts, one relying on finite samples and one relying on asymptotically large samples. They signal whether, on average or with large datasets, a particular statistic is equal to its true value, either in the finite population or in an imagined super-population. The panel uses the term reliability to mean whether the uncertainty surrounding a statistic, measuring how far off it is from a true value (usually measured with confidence intervals), is small enough that one can be reasonably sure (at a particular “level”

of confidence, say 5% or 10%) what the true value in the population is or is not. A closely related concept in statistics is what is called the power of a statistic, which is the ability of a particular statistic from a particular dataset to “detect” a particular value with a reasonable degree of confidence.

With these concepts, when considering the impact on usability of any data analysis system method, the relevant comparison is between the original dataset and the released dataset. Assuming that a statistic from the original dataset can be used to obtain unbiased and consistent estimates of a parameter, the question is whether the released dataset will also allow such estimates to be obtained. In the extreme case in which a variable necessary for the computation of the statistic is not released at all, the answer is clearly no (note that this issue falls under the category of “feasibility” in the classification scheme in Figure 9-1 and will be covered in greater detail in the next section). In other cases, the released data may be so highly distorted from the original that while unbiased and consistent estimates are possible they can only be obtained with difficulty, and only if the user is given the details of the data analysis system method (to be able to compensate for it statistically). For reliability, the right comparison is between confidence intervals and power in the original data versus those intervals and power in the released dataset. A released dataset is effectively unusable if, by comparison with the original dataset, the confidence intervals widen so much and power is so greatly reduced that no reliable inferences can be made.

For any particular statistics obtainable from the original dataset, whether proper inferences can be made and validity can be obtained will depend on the mode of access of the data as well as the information in the released data. The panel listed five types of access at the beginning of this chapter. It is the combination of a particular model with a particular released dataset that determines whether valid and reliable estimates can be obtained. A good example of such an assessment is the study conducted by Stanley and Totty (2023), which compared estimates generated from the SIPP Synthetic Beta dataset with the Gold Standard File (which were discussed both in Chapter 2 and in Chapter 6). The authors found that simple statistics generated from the synthetic data (e.g., means, medians, trends, ordinary least squares coefficients) closely replicated estimates based on gold standard data, but analyses that relied on data features that were not explicitly modeled (e.g., quarter of birth in instrumental variable models) or more complex analyses (e.g., two-stage least squares or factor models) performed less well. Similar designs could be employed to compare original SIPP data (i.e., gold standard) with proposed public-use releases or synthetic datasets. This illustrates how usability interacts with the mode of access (which, in this case, is a synthetic dataset).

While the assessment of accuracy through comparisons with a gold standard is relatively straightforward in principle, the difficulty in applying this methodology to a high-dimensional dataset like SIPP is that there are thousands of different statistics that have been calculated and, looking to

the future, could be computed for any topic area of interest. Any particular data analysis system method, resulting in a particular released dataset to be used in a particular mode, may have little effect on some uses of statistics produced from SIPP, only a modest effect on other uses, and a significant effect on still others, and may make the use impossible for others. In the sections below, the panel reviews the various ways SIPP has been used, aiming to illustrate the wide range of uses to consider when assessing the different dimensions of statistical usability from data analysis system methods.

Once assessments are made of the validity and reliability of SIPP-based estimates for a given data product, it will be important for the Census Bureau to clearly communicate its findings to the SIPP user community. It is possible that estimates based on some variables are more accurate than those based on other variables. For example, for a given synthetic data file, it is possible that estimates of repeated cross-sectional trends in poverty would be highly accurate while estimates of within-person income volatility would be less accurate. Users who study income volatility may then especially depend on the verification process that uses the gold standard data or may seek to access the data in other ways.

FEASIBILITY

Feasibility is a dimension of usability that refers to the degree to which analysts can use the data to investigate the range of scientific questions that the data were designed to answer and, thereby, to obtain valid and reliable estimates, as discussed in the previous section. In the case of SIPP, the key mission is to monitor and study population levels, disparities, trends, and within-person dynamics in public program use, income, poverty, hardship, wealth, and disability, and to monitor and study their relationship with public policies. Of key importance is whether users have access to the variables required to conduct such analyses. A related consideration that impacts feasibility is whether users have access to individual data records and computer platforms that permit them to manipulate the data, including functions that enable users to recode, reshape, and merge data files and conduct statistical analyses.

Feasibility is contingent on the specific ways the data are being used. Rather than trying to evaluate feasibility for any possible way SIPP data could be used, it is important to prioritize uses that build on the key strengths of SIPP data, namely their substantive foci and longitudinal design. To that end, a survey of SIPP research literature identified five broad uses of SIPP data:

- Analyses relying on unique SIPP content (whether for a descriptive or multivariate analysis),

- Longitudinal analyses (including both repeated cross-sectional and within-panel),

- Analyses relying on granular data and complex recoded data (necessary for some policy-relevant analyses),

- Analyses of causal effects of public policies and other analyses that depend on geographic identifiers, and

- Analyses relying on administrative record linkages.

These five uses are examined in more detail, in sequence, in the remainder of this section.

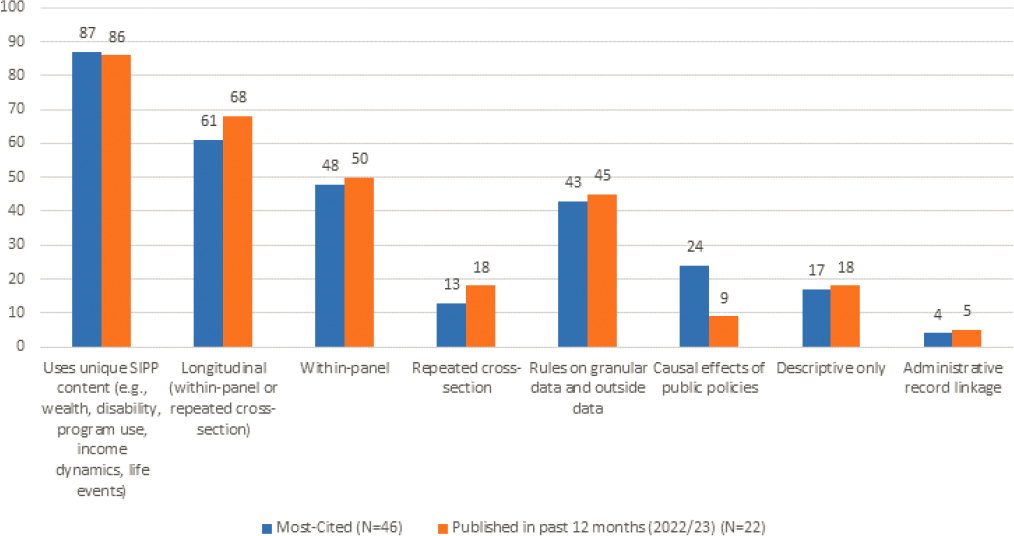

Next, consider the distribution of SIPP research across use categories. This information is important to consider when deciding which uses to prioritize, especially when it is necessary to make tradeoffs between usability and privacy. For this report, the top-50 most cited articles that used SIPP were examined, as measured through Scopus1 (N = 46; four studies were dropped because they did not actually use SIPP data in their main analysis). Because frequently cited articles tend to be older than less frequently cited articles, the panel supplemented this list with every SIPP-based analysis published in the past 12 months (N = 22). Each article was classified according to how SIPP data were used. Note that articles could use the data in multiple ways. For example, a study could be both longitudinal and rely on unique SIPP content. Studies were coded as “descriptive only” if they did not use multivariate statistical analyses. The results are shown in Figure 9-1.

Use 1: Analyses Relying on Unique SIPP Content

SIPP provides uniquely detailed information about income and public program use, income (including poverty, hardship, and wealth), detailed relationships between all household members, and life events (including marriage, cohabitation, fertility, schooling, work, and migration). For example, SIPP has been used to obtain estimates of household clustering in public program use across multiple programs (Borjas & Hilton, 1996), trends in the use of means-tested public programs (Shaefer & Edin, 2013), and trends in children’s coresidence with distant kin and unrelated household members (Pilkauskas & Cross, 2018). This content is a core strength, and its dissemination is central to SIPP’s mission. Yet the rich detail may pose disclosure risks, particularly for individuals who are known to be SIPP respondents.

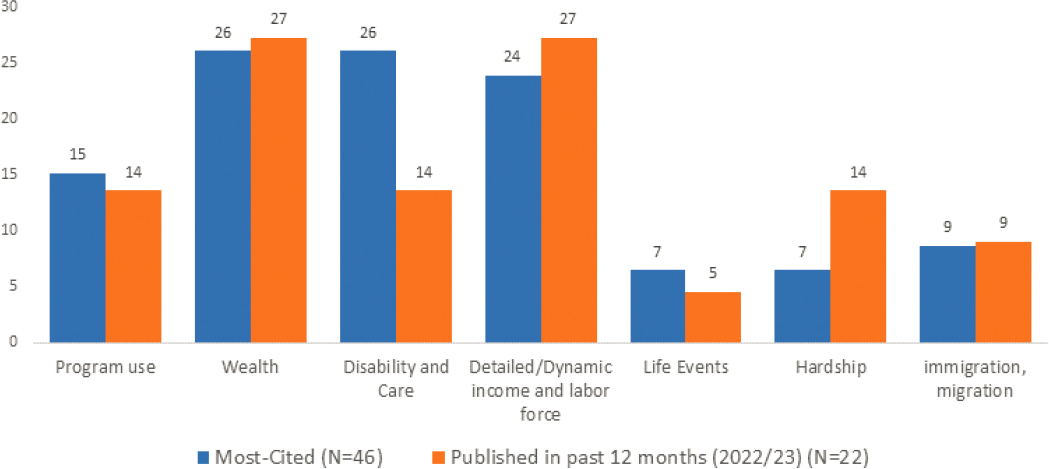

In the analysis of the most cited and recent articles, the key independent and dependent variables were also identified. As shown in Figure 9-2,

___________________

1 Scopus performs a search on titles and abstracts, and would not detect studies that mention SIPP only in the main text. Google Scholar performs a full-text search, and thus detects additional studies; however, Google Scholar counts multiple versions of the same article separately. Google Scholar also incorporates a wider range of literature, while the Scopus review was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles. Both types of searches may identify publications in which SIPP was mentioned but not used as a data source.

NOTES: Each article can be included in multiple categories. Articles were drawn from a search using Scopus on February 7, 2023. The articles included in this literature review are listed in Appendix F.

NOTE: Each article can be included in multiple categories. Articles were drawn from a search using Scopus on February 7, 2023. The articles included in this literature review are listed in Appendix F.

roughly a quarter of the articles relied on data on wealth, disability and care, and (detailed) income or labor force measures as an independent or dependent variable (one exception is that only 14% of articles published in the past 12 months relied on disability or care variables). Roughly 15 percent relied on public programs that use indicators, and between 5 percent and 10 percent relied on SIPP data on life events (e.g., the timing of marriages, births, educational degrees), hardships (with even more among articles on hardship published in the past 12 months), and immigration. Overall, nearly all studies surveyed (86% of the most-cited articles and 87% of recent articles) used variables in these categories as key independent or dependent variables.

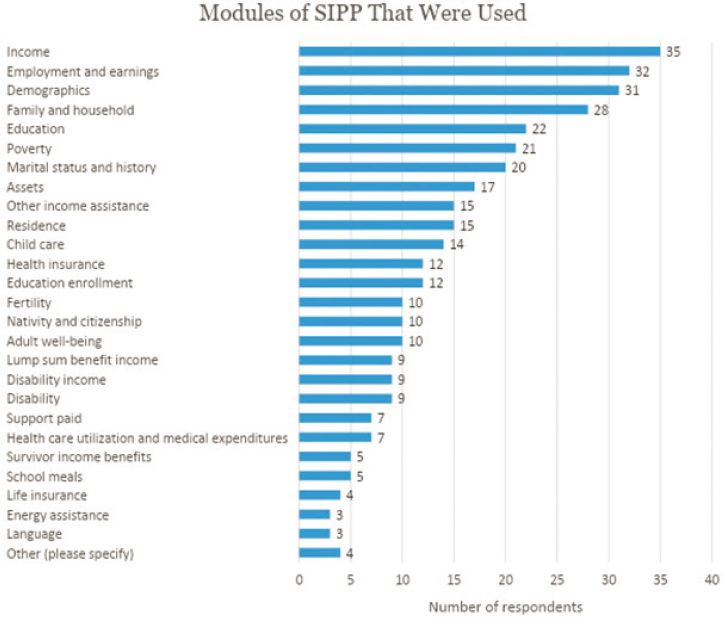

However, while the articles focused on a few key subject areas, their analysis spanned a larger range of areas. Based on responses to the call for information from SIPP users (see Appendix E), most responding SIPP users tend to use variables gathered across multiple subject areas. Though the call for information was not designed to produce nationally representative results, two questions in the call are particularly relevant here. One question asked which components of the data had been used, and another asked in what fields the respondent had published based on SIPP. Every one of 26 listed modules (or topic areas) was used by at least three respondents, with four respondents adding in additional topic areas (Figure 9-3). The most commonly used modules were income, employment and earnings, demographics, family and household, education, and poverty. SIPP data users typically used multiple modules, with every respondent using at least two of the listed modules, and one using all 26. More than half used between one and 10 modules, but if a package of the top 10 modules was created, that would have met the needs of only six of the 41 users. No two respondents used exactly the same set of modules.

This last point is important because one way to reduce disclosure risk might be to create separate, non-linkable files, each with a different subset of variables. For example, one file could include demographics, income, poverty, and program use; another file could include demographics and life history events; and so forth. Nevertheless, the panel’s findings suggest that this approach might not be feasible.

Use 2: Longitudinal Analysis

Another core strength of SIPP is its ability to monitor change. The longitudinal design of SIPP enables users to examine short-term change for individuals, families, and households for the various indicators noted above, including stability and instability in outcomes like employment, income, program participation, household composition, and family structure. A particularly valuable feature of SIPP that distinguishes it from another

SOURCE: Call for information (see Appendix E).

major longitudinal survey, the Current Population Survey (CPS), is that it follows individuals even if they move to new households. The longitudinal data design of SIPP supports statistical methods like fixed-effect models, difference-in-difference methods, event history models, and repeated measurement designs. Assembling multiple SIPP panels over time also enables researchers to monitor trends in outcomes and transitions for groups or populations. This allows SIPP to be used as repeated cross-sections for trends analysis, such as trends in poverty, wealth, marriage/cohabitation, and so on.

Other data sources, such as CPS or the American Community Survey, are also suitable for repeated cross-sectional analysis, but SIPP’s content allows for some use cases not possible in these other data sources. Furthermore, SIPP allows one to combine longitudinal and cross-section applications, such as trends in income instability or program dynamics. However, the detail of longitudinal data, particularly dates of events (e.g., births, marriages), may pose disclosure risks. As with data on program participation and income

(noted above), longitudinal data may require protection through perturbation—that is, through swapping, masking, noise infusion, synthesis, or other techniques. It may be particularly challenging to create synthetic data that adequately represent within-person and within-household longitudinal relationships.

As shown in Figure 9-1, 61 percent of the most-cited SIPP studies and 68 percent of recent SIPP studies capitalized on the longitudinal features of SIPP. Of these, the majority—roughly half of all studies the panel surveyed and about three-quarters of the longitudinal studies—examined within-person or within-household change over time.

Use 3: Analyses Relying on Granular Data and Complex Recoded Data

Data analysts often combine variables in creative ways to extract information that is not directly asked about in the SIPP questionnaire. For example, analysts overlaid respondents’ marriage and birth histories to infer unmarried childbearing (Gibson-Davis, 2011) and multiple-partner fertility (Stykes & Guzzo, 2019). Another study combined information on the timing of the entry and exit of all household members as well as their relationships to the householder and found high levels of household instability among Mexican immigrants due to the rapid entry and exit of friends and non-nuclear kin (Van Hook & Glick, 2007). Still others combine SIPP data with outside information to glean insight about people’s lives. For example, Hall and Greenman (2015) linked SIPP data on occupation to Bureau of Labor and Statistics data on occupational fatalities and hazards. They found that undocumented immigrants are more likely to work in dangerous jobs and were rewarded less in earnings for working in such jobs than other groups.

Of the studies the panel surveyed, nearly half (43% of the most-cited studies and 45% of recent studies) used SIPP data in a complex way as just described. This is important because these kinds of analyses require access to detailed codes (e.g., timing of life events, occupational codes) that have disclosure risks. Such information may be masked or distorted in public data (depending on mode of access), and it is unclear whether synthesized data could account for complex interactions of multiple variables, particularly if measures are constructed with outside information.

These findings are consistent with results from the panel’s call for information from SIPP users. As discussed in Chapter 2, some of the difficulties experienced by SIPP data users of the public-use files reflect their need for extensive and detailed data: eight respondents stopped their analysis or changed their approach because of a lack of detailed data, and four reported that the SIPP files lacked needed measures. Although those reporting difficulties were in the minority (24%), these responses have implications for whether data suppression or recoding would significantly damage data usability.

Use 4: Causal Effects of Public Policies

As mentioned before, SIPP is frequently used to analyze the impact of public policies. Across the studies the panel surveyed, about one-quarter (24%) of the most highly cited studies fell in this category. Fewer recent studies (9%) made causal inferences about policies (the panel suspects this difference is partially attributable to causal analyses being more likely to be cited). These analyses capitalize on SIPP’s rich data on income and program use and on its ability to track changes for individual and family outcomes over time and across a variety of policy contexts. Such analyses often rely on state-level policy variables, whereby state-level policies and policy changes (e.g., Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program rules, minimum wage) are attached to individuals, matching on state of residence (Sabia & Nielsen, 2015). Sometimes, more detailed geographies are required, such as county or metropolitan area (e.g., Ribar, 2005). Policy effects are then estimated with difference-in-difference models, state or county fixed effects models, and instrumental variable approaches, many of which depend on the availability of geographic identifiers.

Despite the importance of this type of work, geographic identifiers are disclosure risks and often may not be released in raw form in public-use data files (as discussed in Chapter 8 relating to SIPP). Because of its reliance on geographic identifiers, public policy research could be particularly sensitive to masking, noise infusion, and synthetic data that distort geographic identifiers.

Use 5: Analyses Relying on Administrative Record Linkages

Finally, SIPP users have linked SIPP data with administrative records from the Social Security Administration and other agencies to supplement information collected in SIPP. This research tends to be highly innovative, yielding new findings that would not be possible with SIPP data alone, such as work on income (Meyer et al., 2021; Medalia et al., 2019) and public program misreporting (Bruckmeier et al., 2014), earnings growth across the life course (Kim et al., 2018; Tamborini et al., 2021), and the long-term self-sufficiency of former welfare recipients (Vaughan et al., 2021). Such analyses require access to administrative data and individual-level linkage variables (i.e., the Protected Identification Key) that are available only at an FSRDC. For this reason, analyses that use administrative data are limited to researchers with access to FSRDCs, typically those at or near institutions with FSRDCs or who have time and money to travel to one.

Only a small share of articles among those surveyed relied on administrative record linkages (4% of the most cited and 5% of the recent articles). This may reflect the costs and difficulties of obtaining access to and working in an FSRDC (a topic discussed later in the section on accessibility), and the fact that most of the published research could be accomplished with public-use data.

After identifying the most common uses of SIPP, it is important to evaluate how difficult it would be to carry out such analyses for the different modes of access. Such an exercise would help ensure that core SIPP strengths remain intact even as changes are made in mode of access. Table 9-1 illustrates how such an evaluation could be organized, with separate evaluations conducted within each cell. One would assess whether the necessary variables, response categories, and linkage variables would be available to conduct the analysis. To consider a simple example, a descriptive analysis of demographic trends or disparities in poverty levels—measures collected routinely in SIPP—may be feasible in any access mode. A specific example is provided in Box 9-1 of a descriptive study of visual impairment, which would be feasible to conduct using the simplest mode of access, an online tabular/analysis builder.

However, a more complex study may be feasible when using some but not other modes of access. Consider a potential study in which a researcher wants to estimate the impacts of working in a hazardous job. The researcher creates a measure of occupational hazard by merging occupational characteristics obtained from an outside source to SIPP respondents’ records. This kind of analysis, relying on granular occupational codes and outside data, is quite common, so the Census Bureau will want to preserve the ability of researchers to conduct this type of study. Yet this kind of analysis would not be feasible to conduct with an online tabular/analysis builder because of the complexity of the data manipulations that would need to occur. Additionally, it is possible that a review of disclosure risk would indicate that the release of granular occupational codes in a public-use file would pose too large a privacy risk. As a consequence, these codes may be suppressed

TABLE 9-1 Matrix for Evaluating Feasibility with the Context of Various Modes of Access

| Uses | Mode of Access | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online analysis builder | Public-use microdata | Synthetic data | SODA | FSRDC | |

|

|||||

from the public-use data, thereby making them inadequate for the analysis. Synthesized data may also be inadequate, because such data would not necessarily account for outside data on occupational characteristics; the relationships of interest are unlikely to have been modeled when the synthetic data were created. However, the study may be feasible to conduct through SODA. Another example of a feasibility analysis for a similarly complex longitudinal study on the effects of spouses’ work on employment is provided in Box 9-2.

Overall, a feasibility analysis such as illustrated here will help the Census Bureau anticipate how changes in mode of access will impact the volume and type of research being conducted with SIPP data.

ACCESSIBILITY

Accessibility is a dimension of usability that refers to the cost and difficulty of accessing data. As accessibility declines, the number of SIPP users will also likely decline, particularly among those with fewer resources, reducing the potential impact of SIPP. An important task facing the Census Bureau is to determine how users would be impacted by making particular

modes of access available or unavailable, how the impact would vary across different user groups, and how to mitigate any negative consequences.

In Table 9-2, three types of users are considered: (1) those with limited resources and expertise, such as undergraduate students and researchers without access to Institutional Review Boards (IRBs); (2) those with moderate levels of resources and expertise, such as researchers at lower-resourced institutions, some nongovernment think tanks, or researchers-in-training such as graduate students; and (3) users with high levels of resources and expertise, such as researchers who have grant funds and work at FSRDC member institutions with the staffing to manage Data Use Agreements and are close to an FSRDC.

Additional user categories may be required to recognize users with distinctive data needs. The survey of SIPP publications described earlier suggests that the bulk of SIPP users probably fall in the second and third categories above—that is, those with the greatest resources available. Nearly all the first authors were faculty members at universities or researchers in

| User Type | Mode of Access | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Table maker | Public-use microdata | Synthetic data | SODA | FSRDC | |

|

4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

|

4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|

4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

NOTE: The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education divides institutions into multiple categories. Among doctorate-granting universities, R1 universities have the highest level of research activity, R2 universities have the next highest level, and R3 universities have the least. Other categories include baccalaureate colleges, master’s colleges and universities, baccalaureate/associate’s colleges, and associate’s colleges.

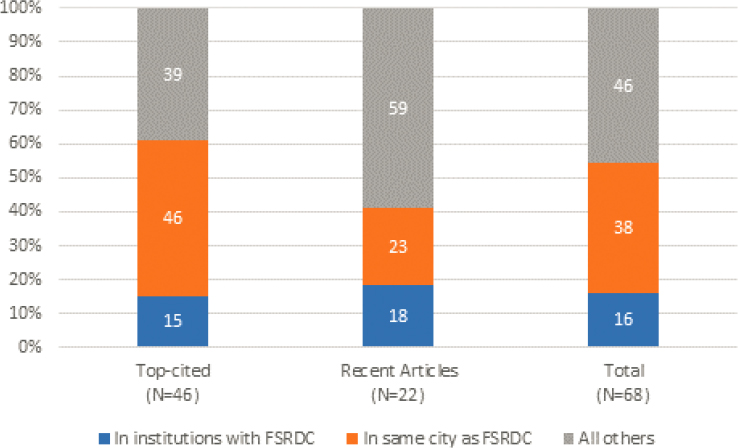

research organizations. Sixty-one percent of the first authors of the top-cited articles were either based at institutions that hosted an FSRDC (15%) or worked in a city with an FSRDC (46%; Figure 9-4). The first authors of recently published articles were not as proximately located: 41 percent were located near an FSRDC (18% in the same institution and 23% in the same city). Nevertheless, between 40 percent and 60 percent were not located near an FSRDC, which would likely pose challenges to users if SIPP data were modified in such a way that they could no longer use them to conduct their work unless they did so in an FSRDC.

Moreover, it is critical to note that proximity to an FSRDC does not fully capture the barriers to working in an FSRDC. Regardless of their proximity to an FSRDC, most published data analyses that the panel surveyed were based on public-use data, and only 4 percent required access to restricted data. The panel’s SIPP user survey yielded similar results. In that survey, the panel asked about three current modes of access: public-use microdata files, synthetic SIPP data, and restricted SIPP data available in the FSRDC. The respondents were most likely to have reported using the public-use file. Out of 65 respondents, 42 downloaded the public-use file, 18 accessed the synthetic data, 17 downloaded tables or reports, and only seven (11%) accessed the data through an FSRDC. Two of the respondents had used all four sources, 24 used only one, and 24 used some combination of multiple sources. Overall, this suggests that even for data users who are located near an FSRDC, either there are considerable barriers to accessing them or no need to use them because the public data file was sufficient.

After classifying users according to their data needs and ability to access restricted data, it is important to evaluate their ability to access SIPP data for each proposed mode of access. To illustrate how accessibility might be evaluated, Table 9-2 is populated with qualitative assessments of the ability of each user type to access SIPP data using the various access modes, indicating a “high” (= 4), “moderate” (= 2 or 3), or “low” (= 1) likelihood of accessing the data. These evaluations are based on the professional experience of panel members; empirical estimates of access could be gathered through online user surveys.

It is unlikely that low-resourced users (e.g., undergraduate students) would be able to use any SIPP data source unless it were made available through an online tabular/analysis builder or public-use file. Members of this group generally do not have the funding or institutional support to access restricted-use data, and only some have sophisticated data analysis and statistical skillsets. This group would stand to lose the most if public data were no longer available. At the other end of the scale, high-resourced users could probably access data regardless of access mode, although making SIPP data available only in a highly restrictive environment would slow down research or steer researchers away from SIPP and toward other data sources, such as the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), that are less difficult to access. In contrast to low- and

high-resourced users, the moderately resourced users would gain the most from the availability of synthetic data or SODA. They would use microdata and administratively linked SIPP data if they could but would also be stymied if the costs of accessing the data were too high. As discussed in the next section, the costs of accessing data through an FSRDC can be quite high—prohibitively so for all but the high-resourced users. However, the costs of accessing SIPP data through SODA may be considerably lower for moderately resourced users. Many researchers in this group already access other data through SODA (e.g., PSID, National Center for Education Statistics, Add Health, and Health and Retirement Study data), and they are accustomed to working within the confines of Data Use Agreements.

SODA thus provides the best current prospect for maintaining usability among both low- and moderately resourced SIPP users.

How the Introduction of SODA and Reinterpretation of Title 13 Would Affect Accessibility

Here a more detailed illustration is provided on how the addition of a new mode of access—namely, SODA—could enhance accessibility for users. Such an addition would likely entail a reinterpretation of Title 13, particularly if SODA users were not required to obtain Special Sworn Status or demonstrate a direct benefit to the Census Bureau (an issue the panel discusses later in this chapter). Note that Chapter 5 further details how SODA can expand access to restricted data.

For researchers who wish to use the restricted SIPP data, obtaining approval through the current FSRDC system requires a multistage process that can take several months. The proposal must demonstrate that the research project’s predominant purpose is to benefit Census Bureau programs, and this criterion carries the greatest weight during the approval process over other considerations, including scientific merit, need for restricted data, and feasibility. Approval or exemption from an IRB is also required.

Applicants must also obtain and annually renew a Special Sworn Status. Non-U.S. citizen researchers must have lived in the United States for longer than 36 out of the prior 60 months and be affiliated with a U.S.-based institution. Clearances for non-U.S. citizen applicants take longer to complete. The Department of Homeland Security administers Special Sworn Status applications and researchers must submit fingerprints; complete online training; submit residential, travel, employment, and education histories; provide references; and complete an interview. Doctoral students who are applying for restricted data must have a faculty advisor who also has a current Special Sworn Status.

The applicant’s institution can facilitate approval to access restricted data. Researchers who are not affiliated with institutions that can enter Data Use Agreements or have IRBs are at a disadvantage when preparing their proposals. Those who are not based at one of the 50 FSRDC partner organizations must pay an additional fee.

The structure of the current FSRDCs creates unequal barriers to accessing the restricted data even for proposals and researchers that are cleared for FSRDC access. Applications, approvals, and fees are specific to a single Restricted Data Center (RDC) location, and multisite research teams can incur additional costs to gain access to multiple RDCs. Researchers must renew their Special Sworn Status annually, and changes in affiliation, title, or members can cause interruptions. Travel to physical RDC locations can become costly, especially for researchers who are not close to an RDC or do not have funding dedicated for data access expenses.

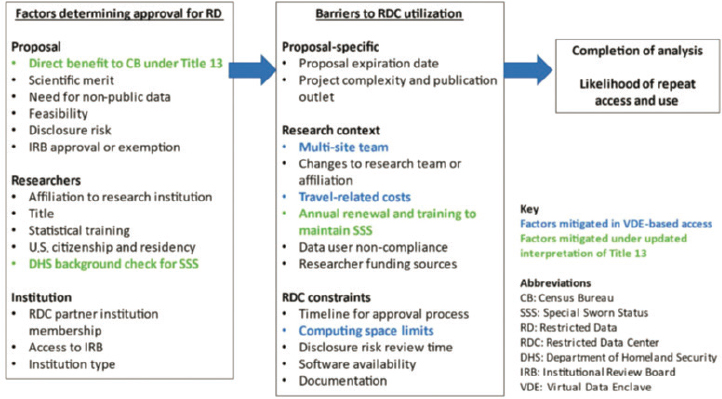

However, as described in Chapter 5, expanding access through SODA or by reinterpreting Title 13 (a possibility the panel discusses at the end of this chapter) to enable access to formerly public-use data without the need for Special Sworn Status or a long and detailed proposal would help researchers avoid the additional administrative and cost burdens of conducting research in an FSRDC. This is illustrated in Figure 9-5, where the barriers to access that would be mitigated if data were provided via SODA

NOTE: Green text indicates barriers to access that would be mitigated through a reinterpretation of Title 13, and blue text indicates barriers that would be mitigated through SODA.

are shown in blue, and other barriers to access that would be mitigated through a reinterpretation of Title 13 are shown in green.

To conclude this section on usability, more research on the user community might be conducted to assess the number and types of users who would be most impacted if certain modes of access were eliminated (e.g., a public-use file) or if new modes of access were made available (e.g., SODA). However, the panel’s preliminary research suggests the following points.

First, to maintain the value of SIPP data (and, accordingly, the size of the current SIPP user community), it will be important for the Census Bureau to continue to produce a public-use microdata file if the disclosure risks are sufficiently low to do so (see Chapter 3 for more discussion on this topic). Most SIPP research is currently conducted on the public-use file, and a large share of SIPP users do not have easy access to an FSRDC.

Second, to the degree that the public-use SIPP microdata become less useful due to efforts to increase privacy protections, the Census Bureau should consider providing mid-tiered access to restricted SIPP data through SODA. Current SIPP users tend to be sophisticated data users. Most of the analyses performed on SIPP are conducted by faculty members, graduate students, and professional researchers. This sophistication is reflected in the types of data analysis they perform, most of it being multivariate analyses that involve complex data recodes, longitudinal analysis, and incorporation of outside data sources. For many SIPP users, certain modes of data access will be inadequate for their work, such as an online tabular/analysis builder or public data that suppress variables like state, occupation, or industry.

This last conclusion was further backed by input from SIPP users as described in Chapter 2, who reported using both tabulations and statistical modeling when working with SIPP data, and most of whom reported using data for longitudinal and cross-sectional analyses. Only 7 percent said their research needs could largely be met through the availability of a comprehensive set of standardized tables. By contrast, roughly three-fourths of users said that using standardized tables would meet their research needs only to a small extent (31%) or to no extent at all (43%). At the same time, the analysis of SIPP publications indicates that roughly half of the first authors are not located near an FSRDC. A simple reflection about the steep requirements of working in an FSRDC, combined with the panel members’ professional experience, suggests that most researchers would consider accessing an FSRDC burdensome.

Third, to increase the size of the SIPP user community and expand the uses of SIPP data beyond their current scope, the Census Bureau might consider investing in highly accessible modes of access that do not require specialized skills in data analysis, such as an online tabular/analysis builder. This particular mode of access is described in detail in Chapter 7. A review of SIPP publications revealed that about 18 percent of studies are based

solely on descriptive analyses, all of which could be conducted with an online data analysis tool (see Box 9-1 for a description of such a study). The availability of a simple online analysis tool has the potential to expand the use and value of SIPP data for the purpose of descriptive analysis for people who have not historically used SIPP data and who may not have the skills to analyze microdata. Nevertheless, it is not at all clear that “if you build it, they will come.” More research would help identify the number and types of people who currently do not use SIPP but who would benefit from such a tool. Still further work would be involved to reach out to this group and provide training in the value of SIPP and the use of the online analysis builder.

TITLE 13 AND DATA ACCESS

A key question is whether the full set of restrictions to data access applied in FSRDCs must necessarily be applied in other tiers. This section evaluates that topic and concludes that the Census Bureau has much more flexibility in how data may be released under Title 13 than has been commonly viewed.

Title 13 defines the role and functions of the Census Bureau, and it contains provisions designed to both direct and authorize the Census Bureau to protect the confidentiality of its data. The title’s provisions are thus very important when considering disclosure avoidance for SIPP. The key sections regarding confidentiality are 9(a), 23(c), and 214. Section 9(a) limits the uses of the data, prohibits the release of identifying information, and limits access to the data to sworn officers. Section 23(c) provides a vehicle for outside individuals to access the data. Section 214 specifies the penalties for unauthorized release of Title 13 data (the penalties were later increased under the Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act and the Evidence Act to $250,000).2

§9(a). Neither the Secretary, nor any other officer or employee of the Department of Commerce or bureau or agency thereof, or local government census liaison, may, except as provided in section 8 or 16 or chapter 10 of this title or section 210 of the Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 1998 or section 2(f) of the Census of Agriculture Act of 1997—(1) use the information furnished under the provisions of this title for any purpose other than the statistical purposes for which it is supplied; or (2) make any publication whereby the data furnished by any particular establishment or individual under this title can be identified; or (3) permit anyone other than the sworn

___________________

2 44 USC § 3572(f); https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-115publ435/pdf/PLAW115publ435.pdf

officers and employees of the Department or bureau or agency thereof to examine the individual reports.

§23(c). The Secretary may utilize temporary staff, including employees of Federal, State, or local agencies or instrumentalities, and employees of private organizations to assist the Bureau in performing the work authorized by this title, but only if such temporary staff is sworn to observe the limitations imposed by section 9 of this title.

§214. Whoever, being or having been an employee or staff member referred to in subchapter II of chapter 1 of this title, having taken and subscribed the oath of office, or having sworn to observe the limitations imposed by section 9 of this title, or whoever, being or having been a census liaison within the meaning of section 16 of this title, publishes or communicates any information, the disclosure of which is prohibited under the provisions of section 9 of this title, and which comes into his possession by reason of his being employed (or otherwise providing services) under the provisions of this title, shall be fined not more than $5,000 or imprisoned not more than 5 years, or both.

This wording allows much broader access to data than has often been recognized:

- It allows the Census Bureau to determine which data should be protected, only saying that establishments and individuals should not be identified. The Census Bureau once treated that definition as applied to information such as names and addresses but has been broadening that definition.

- It states that the data should be used for the statistical purposes for which they are supplied.

- It leaves unspecified the procedures for determining which people and projects are authorized to access the data.

- It leaves the mode and rules for data access unspecified.

To clarify and implement Title 13, the Census Bureau has adopted two policies—DS002 and DS006. Policy DS002 states that a project must deliver a benefit to the Census Bureau’s programs and activities, and that the benefit must be the predominant purpose for conducting the project.3 The policy lists 13 criteria for determining if the Census Bureau is benefited.4 At least one of the 13 criteria must be satisfied: the first four apply generally to Title 13 data, while if federal tax information is to be used then at least one of the remaining nine criteria must be satisfied. In summary, the

___________________

13 criteria require that the project benefit the Census Bureau by seeking to accomplish one of the following:

- Evaluating the Census Bureau’s data or reports;

- Analyzing trends that affect the Census Bureau’s programs;

- Increasing the utility of the Census Bureau data;

- Facilitating data collection, processing, or dissemination;

- Helping understand or improve the quality of data;

- Leading to new or improved methodology;

- Enhancing the data;

- Identifying limitations or improving the sampling frames or classification schemes;

- Identifying shortcomings of current data collection programs or documenting new data needs;

- Constructing, verifying, or improving the sampling frame;

- Preparing population estimates;

- Addressing non-response; or

- Developing statistical weights.

These criteria add considerable specificity to the language contained in Title 13 (“assist the Bureau in performing the work authorized by this title”) and generally focus on improving the Census Bureau’s operations or the data file itself. However, some of the criteria could be given a broader meaning. For example, one might argue that examining the interrelationships among variables (e.g., documenting that it is important to adjust for differences in race/ethnicity) ultimately increases the utility of the data (Criterion 3) and helps to understand the data (Criterion 5). However, a lack of clarity makes it difficult for potential data users to know whether a data request is likely to be accepted, potentially preventing the submission of what would be considered acceptable proposals. The criteria also tend to imbed the assumption that the Census Bureau’s purposes are only to collect and distribute the data, not to encourage use of the data or support policy or social science research.

Policy DS006 defines how non-employees may access Title 13 data. It sets three criteria for determining if a project qualifies, three individual/organization criteria for determining who may receive Special Sworn Status, and four criteria for determining if a project can take place at a non-Census Bureau facility. In sum, the project must require access to Census Bureau confidential data, benefit the Census Bureau’s Title 13 Programs, and be viable. The individual and organization must have a good track record for handling sensitive or confidential data, have no identified conflict of interest, and pass a background investigation. Access to the data off-site depends

on the type of project proposed (internal, joint, reimbursable, external, or oversight). External projects must be carried out at a Census Bureau facility (including FSRDCs), while other projects may be granted an exemption if they provide a technical or logistical advantage, meet required security models, have legal or regulatory functional separation of the data collected for statistical purposes (for governmental agencies or organizational units), and obtain Data Stewardship Executive Policy Committee approval prior to any major commitment of resources.

Again, these criteria add considerable specificity to the goal that temporary staff must be “sworn to observe the limitations imposed by section 9 of this title.” For example, Title 13 does not say that such researchers must be prequalified, let alone how they should be prequalified.

Because many of the specifics are contained in policies rather than in Title 13 itself, it is possible to change many of the requirements without changes in legislation. In fact, the rules have been updated in the past; they were originally established in 2002,5 while DS002 was last signed in 2018, and DS006 was updated in 2009 (in this case, only to update organizational names).

One aspect of change, and a key focus of this report, is that the definition of personally identifying data is evolving. It once focused on names and addresses, but there now is a recognition that many data elements present disclosure risks to the degree that similar data can be found in and matched with other databases. The federal government’s priorities also have changed, giving a high priority to increasing access to data and to using tiered access as a tool for supporting that goal. The Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB, 2013) guidance on the Information Quality Act states the following:

Implementation Update 3.4: Agencies should prioritize increased access to the data and analytic frameworks (e.g., models) used to generate influential information. All data disclosures must be consistent with statutory, regulatory, and policy requirements for protections of privacy and confidentiality, proprietary data, and confidential business information.

Implementation Update 3.S: Agencies should explore methods that provide wider access to datasets while reducing the risk of disclosure of personally identifiable information. In particular, tiered access offers promising ways to make data widely available while protecting privacy. Implementation of such approaches must be consistent with principles for ethical governance, which include employing sound data security practices, protecting individual privacy, maintaining promised confidentiality, and ensuring appropriate access and use.

___________________

5 www.governmentattic.org/6docs/CensusBureauDataStewardship_2002-2010.pdf

To ensure reproducibility, the Guidelines set an expectation of access to data underlying influential information, subject to “compelling interests such as privacy, trade secrets, intellectual property, and other confidentiality protections.” Since the 2002 Guidelines, the technology for allowing protected access to data has progressed significantly. New approaches to secure data access using cutting-edge technologies reduce the risk of reidentification and therefore may mitigate certain privacy risks associated with providing such access. Risk reduction techniques include creating multiple versions of a single dataset with varying levels of specificity and protection (sometimes referred to as “tiered access”).

The virtue of tiered access is that data users who wish to conduct activities with a statistical purpose without first obtaining special authorization have access to the versions of the data in the least restricted tiers, allowing them to conduct research while protecting confidentiality. Such approaches to increasing access to data for statistical purposes could be considered by more federal agencies, thereby allowing stakeholders to replicate analyses and explore the sensitivity of the conclusions to alternative assumptions while accessing only the data they need. As agencies consider adding intermediate tiers between fully open and fully closed, they must build in sufficient controls to monitor who is accessing the data and allow access only for authorized purposes. (Office of Management and Budget, 2019a)

Tiered access serves a dual function. First, it allows increased access to data that otherwise might not be available, helping to keep SIPP data usage from being undercut if some data in the public-use file are found to be disclosive. Second, and at the same time, tiered access protects data security through data minimization, “giving access to the least amount of data needed to complete an approved project” (Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, 2017, p. 38). The federal government’s move toward increasing access to data, while also respecting confidentiality, is also expressed in the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 (Evidence Act; Office of Management and Budget, 2019b). From this perspective, the largely internal approach to defining “benefit” in Policy DS002 is no longer appropriate.

The Census Bureau might consider modernizing its interpretation of Title 13 in several ways.

- First, Title 13 does not require that data access benefit the Census Bureau specifically, instead focusing on accomplishing the work of the Census Bureau. Since part of the work of the Census Bureau is to support research and open access to data, the criteria specified in Policy DS002 are fine in themselves, but additional and more broadly based criteria might be added. When the Census Bureau

- determines that a survey such as SIPP accomplishes its purposes, then supporting research based on the survey also accomplishes its purposes.

- Second, the purposes of the Census Bureau are also defined by Title 44 (also known as the Evidence Act), which applies to all federal statistical agencies. Thus, expanding data access for evidence building might also be considered as a benefit to the Census Bureau.

- Third, while Title 13 requires that users be sworn to protect confidentiality, it does not impose conditions on who may be sworn. DS006 requires a background investigation, which itself involves additional criteria (e.g., it is very difficult for a non-U.S. citizen to be authorized). These requirements are both excessive and time-consuming. The process of preparing a justification and application package itself is onerous. Conducting some kind of review is appropriate, but the Census Bureau might examine what other agencies and organizations are doing and create a simpler and more expedited process.

- Fourth, rather than offering a largely dichotomous choice between public-use data and FSRDCs, the Census Bureau should consider allowing for multiple levels of security depending on the sensitivity of the data. Some types of data, such as names and addresses, deserve a very high level of security, and blended administrative data often do as well, since these may have a separate set of restrictions that is imposed by another agency. Other data might be deemed less sensitive, requiring more constraints than a public-use file but fewer constraints than an FSRDC. The Census Bureau has already moved in this direction by offering the Synthetic Beta file and by increasing virtual access to Title 13 data. To the degree that re-identification studies indicate that some of the public-use data present a disclosure risk, these data might be moved to an intermediate security level rather than being available only through FSRDCs.

The panel is not taking a position on whether the conditions for access to FSRDCs should be revised, other than supporting the Census Bureau’s recent move to allow virtual access to the data. Based on the logic presented above, it would be possible to change the conditions for access to FSRDCs, since these conditions are based on policy decisions on how to implement Title 13 rather deriving from Title 13 itself. However, FSRDCs would contain the most sensitive SIPP data, which deserve stronger levels of access, and FSRDCs often are used for blending data from other sources, meaning that the restrictions imposed by other agencies also are a factor.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusion 9-1: The research studies based on the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) use many variables covering many different topics. Selecting only a limited set of modules for public release will not satisfy the needs of many SIPP users.

Conclusion 9-2: A formal evaluation of the tradeoff between risk reduction and usability would help inform the selection of disclosure limitation approaches for different tiers of access to Survey of Income and Program Participation data.

Conclusion 9-3: Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) users and potential users have a variety of needs, and a single mode of access is unlikely to suit all of them.

- Most SIPP data users’ needs cannot be met by providing standardized tables, while accessing SIPP data only through a Federal Statistical Research Data Center would be overly burdensome for many SIPP data users and create inequities in access.

- An online tabular/analysis builder for accessing SIPP data has some potential for expanding the SIPP user community to include those who may not have the analytical skills or resources to work with the public-use microdata files.

- Public-use files provide users with the level of control that they need in working with the data.

- A mid-tier mode of access—such as secure online data access—would provide for those situations in which desired data are not available on a public-use file.

Conclusion 9-4: Survey of Income and Program Participation respondents and potential respondents would benefit from a better understanding of the disclosure limitation methods used to protect their information and how these methods safeguard confidentiality.

Conclusion 9-5: Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data users would benefit from additional communications regarding changes to data access and disclosure protection, how to use SIPP data, how to compute standard errors in the presence of added noise to protect data, and the types of analyses that can be conducted using various tiers of access. Forms of communication could include documentation, workshops and webinars, and sample code. Carrying out statistical

inferences on confidentialized data will require releasing details of the disclosure limitation methods.

Conclusion 9-6: Title 13 requires that confidentiality be protected but does not specify the means of protection. The current use of Special Sworn Status and Federal Statistical Research Data Centers is based on the policy interpretations of Title 13, not on Title 13 itself.

Recommendation 9-1: The Census Bureau should conduct regular assessments of the validity and reliability of estimates generated from Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data products treated for disclosure protection and communicate the results to SIPP users.

Recommendation 9-2: When considering which access modes to prioritize, the Census Bureau should evaluate feasibility for the most common Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) uses and those that exploit the unique characteristics of SIPP and could not be obtained from other datasets.

Recommendation 9-3: The Census Bureau should seek to continue providing public-use files for Survey of Income and Program Participation users, assuming that appropriate disclosure avoidance techniques can be adopted and that disclosive and sensitive variables are treated for disclosure avoidance. The variables to be included should depend on the results of disclosure risk studies.

Recommendation 9-4: Given the differences in user needs and approaches, the Census Bureau should offer multiple tiers of access, with approaches for confidentiality protection applied.

Recommendation 9-5: The Census Bureau should modernize its interpretation of Title 13 consistent with changes in technology, policy guidance, and legislation (i.e., the Evidence Act and the Information Quality Act). Doing this should enable the development and operationalization of tiered data access in which (a) the types and levels of protection and access vary across tiers; (b) the requirement of benefit is redefined to include evidence building, the productive use of Census Bureau–developed data, and other statistical purposes; and (c) the types of individuals who are eligible to access the data in these tiers are broadened.

This page intentionally left blank.