6

Plan Execution

This chapter describes how air traffic controller (ATC) candidates are recruited, screened, hired, initially trained, and placed in facilities by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for On-the-Job (OTJ) and other training and the time periods required to achieve full certification as a Certified Professional Controller (CPC). It also covers the role of transfers in facility staffing. This chapter responds, in part, to elements of the study’s Statement of Task to:

- “Identify and assess factors relevant to controller staffing levels and planning by analyzing historical data and metrics for factors such as operations workload, Time on Position (TOP), Other Duties, planning decisions and training execution, certification progression, overtime and leave usage, and planning and scheduling activities”; and

- “Assess FAA’s progress in furthering the recommendations in [the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) 2014 report] ‘The Federal Aviation Administration’s Approach for Determining Future Air Traffic Controller Staffing Needs.’”

Some of the items above regarding facility staffing levels, historical records of TOP and Other Duties, leave usage, and scheduling are addressed in Chapters 2–5. This chapter focuses on other elements of plan execution: recruitment and hiring process, training execution, certification progression, and transfers between facilities for strength management.

FAA sets facility-level targets for CPCs and CPCs-In Training (CPC-ITs) based on the FAA Office of Finance and Management (AFN) modeling process described in previous chapters.1 How CPCs, CPC-ITs, and Developmental Controllers (DEVs) end up at the facilities that need them depends on policies and strategic direction at the national level that set hiring levels, training goals, and influence placements in facilities as well as on the transfer process. The hiring with intent to meet facility staffing targets was reviewed in Chapters 2 and 5. This chapter’s first section describes how controller candidates are recruited, hired, provided initial training at the FAA Academy, and then staffed and provided OJT at a facility. The second section describes trends in training success rates and the time period required to produce CPCs. The third section reviews the results of transfers across the workforce, including to supplement staffing at understaffed facilities. The fourth section reviews the NASEM 2014 report recommendations made about plan execution and FAA’s responses to them. The final section provides the committee’s findings and recommendations.

RECRUITMENT, HIRING, INITIAL TRAINING, AND INITIAL PLACEMENT

This section begins with an overview of the process for producing a fully certified controller, from candidate recruitment to initial placement at a facility for OJT (a DEV is considered “staffed” upon this initial placement, though their contribution to managing aircraft traffic begins only when they are at least partially qualified at that facility). This discussion is followed with more detail about efforts by FAA to improve, through streamlining and other means, the stages of recruitment, hiring, screening, initial training, and placement at facilities for OJT.

Overall Process from Application to Certification

Candidates to become CPCs go through a multistep process that can require an average of more than 5 to 5.5 years to complete, from receiving a tentative hire offer to CPC certification (fully qualified status). There are two pools of candidates who apply, those with and without controller experience. The following description focuses mostly on the pool of applicants from the General Public (GP) who lack experience, while noting exceptions to the steps for graduates of College Training Initiative (CTI) schools,2 and

___________________

1 Although the AFN target is defined as CPCs and CPC-ITs, the staffing generated by the models is based on position-qualified controllers, which includes DEVs, as described in Chapter 5.

applicants with Prior Experience (PE) as controllers. A simplified version of the steps for each pool is provided in Box 6-1.

For the GP pool, FAA has traditionally offered a single, typically 5-day, application window early in the federal government’s Fiscal Year (FY). (In FY 2024 FAA experimented with two application windows.) Those who apply during this window are then assessed for basic eligibility (U.S. citizen, fluency in English, age 31 or younger, and 1 year or more year of work experience). (Note that at the time of this writing in May 2025, FAA is considering raising the age 31 threshold to increase the number of applicants.) Applicants deemed eligible must then take FAA’s screening test, the Air Traffic Skills Assessment (ATSA). Those who earn a “well qualified” score on the test and are deemed appropriate by the Air Traffic Organization (ATO) are given a tentative, or provisional, hire offer subject to clearing medical and security screening. New hires who pass medical and security screening are given a class assignment at the Academy to undergo training for a period of 3–5 months, depending on whether they have graduated from a CTI school and whether they are (randomly) assigned to the Terminal or Center Track. Graduates of the CTI schools can skip the 5-week “Air Traffic Basics” class at the Academy and thereby graduate sooner. CTI school graduates have two annual application windows.

BOX 6-1

Steps from Hiring to Certification and Transfer

General Public (GP) and College Training Initiative (CTI) Graduates Terminal Track

Recruitment →Screening →Hiring →Academy Class Assignment →Academy Training →Level 4–7 Facility Placement →OJT →Certification →Transfer to Higher-Level Facility →OJT →Certification

Centers Track

Same as above except Academy Graduates (AGs) are placed in Centers, which are Level 10–12 facilities.

Previous Experience (PE)

All steps the same except (a) the hiring window and hiring are occurring year-round as of 2024 and (b) after hiring candidates are placed directly into facilities for OJT.

AGs are placed in facilities for OJT. Some AGs are assigned to the Terminal Track according to a random assignment process. They are usually placed in Level 4–7 facilities to gain experience, and in part to avoid higher attrition rates experienced by AGs training at higher-level Terminal facilities too early. AGs who certify to CPC at their initial facility may choose to stay at that facility or transfer to a higher-level facility that offers higher salaries. AGs in the Center Track are sent to Centers for training, all of which are Level 10–12 facilities. The Centers tend to have larger controller staffs (averaging 267 in FY 2024 compared to an average of 72 at Terminal Radar Approach Controls [TRACONs], 18 at Towers, and 27 at combined Tower and Approach Control Terminals). ATO indicated to the committee that the Centers have formal on-site classroom-based OJT training to support AGs in meeting the challenge of certifying at facilities with the most complex airspace.

Applicants from the PE pool are also required to take FAA’s screening test and pass medical and security clearances. Successful PE applicants then bypass the Academy and are placed in a facility for OJT, which are almost always Terminals.

Hiring, Attrition, and Approximate Timelines to CPC Status

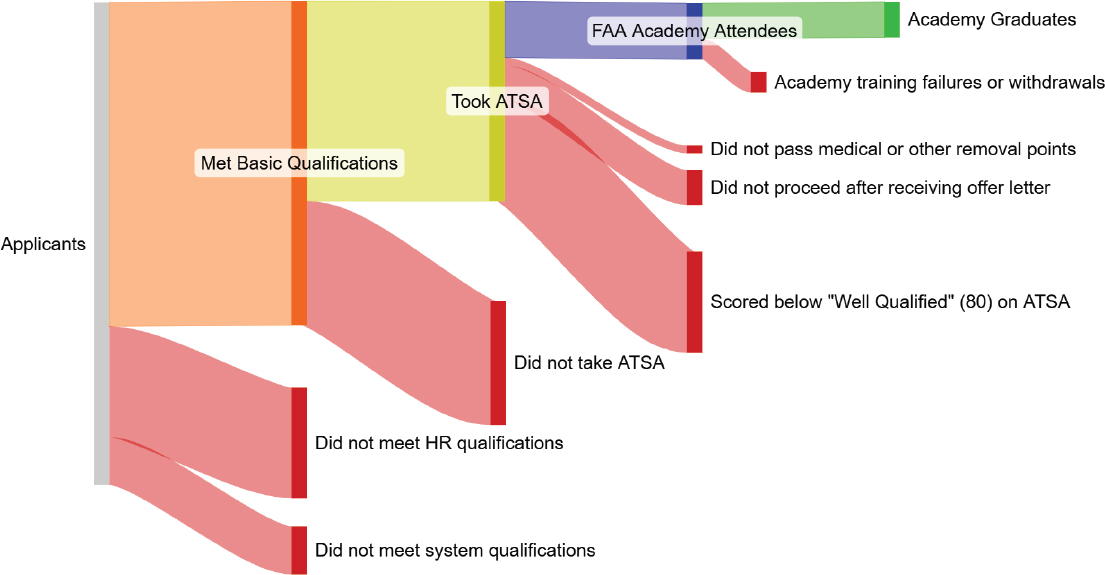

FAA generally receives 12,000 to 13,000 GP and CTI applications and 1,000 to 1,400 PE applications each year (but more in FY 2024 as explained below).3 In FY 2024, which was fairly typical of experience since 2018, FAA received 11,819 GP and 1,040 CTI applications. Of this combined group of 12,859 applicants, 8,625 (67%) were deemed qualified to take FAA’s screening test (described below) for their compatibility with the Knowledge, Skill, and Abilities (KSAs) that FAA requires. Of this qualified group, 5,329 (62%) elected to take the screening test, while the rest declined despite the urging of FAA (see Figure 6-1).

All candidates who receive a “well qualified” rating (a score of 85% or higher) from the ATSA screening test are given a tentative hire offer, “tentative,” as in subject to receiving medical and security clearance. Typically, about half of well-qualified candidates make it through these clearances, but it can take 2 years or more for some candidates to achieve medical or security clearances if there are issues raised that have to be resolved. In FY 2024, 41% of the 5,329 candidates who took the screening test scored 85% or higher, whittling down the 12,859 original applicant pool to 2,184 available for tentative hire selection. It merits noting that in FY 2024, FAA began an “Enhanced” CTI (E-CTI) initiative. Graduates of E-CTI schools can skip

___________________

3 These and following numbers provided in FAA presentation to the committee on October 9, 2024.

the Academy entirely and begin their training at individual facilities. (E-CTI school graduates are expected to be a small share of applicants unless the number of schools offering this training expands beyond the five currently in the program as of the time of this writing in May 2025.)

In FY 2024 more than 3,500 PE candidates applied in the first year of year-round hiring announcements, but many had not yet been processed by the date of the October 2024 briefing to the committee. In FY 2023, the year before year-round hiring, 1,339 PE candidates applied, 779 (58%) were referred to ATO, and 752 (56%) were selected as potential hires. Of this group, 243 were hired and assigned to facilities for OJT (18%). Since most PE hires come from the military, which only has tower and approach control ATC services, the vast majority are placed in Terminal facilities. (Since 2015 a total of only 30 PE hires were placed in Centers, most of whom had previously worked for FAA.)4

In October 2024 (the start of FY 2025), FAA announced it had hired 1,811 applicants.5 This slightly exceeded the hiring goal it set of 1,800. Thus, of roughly 14,200 applicants from both pools, 12.7% were hired. For most members of this group, the duration from application to hire to the assignment for Academy training was completed in 6–10 months. (In the following descriptions, 1 year is used as an approximation of the average duration from application to firm hire offer to account for those for whom medical and security clearances can take up to 2 years.)

Of this total group of hires (both GP and PE), roughly 65–75% will complete training and achieve CPC status. For FY 2023–2034, about 1,250 of the 1,800 hires may certify as CPCs, but other estimates from FAA indicate the number may be about 900.6 As discussed later in this chapter, this process takes roughly 2–5 years depending on the type and Level of facility and individual aptitude. This remaining group, after training losses, represents about 9% of applicants. (As noted in the previous chapter, FAA takes this expected attrition into account when it sets its hiring goals.)

With this process and timeline in mind, the next sections will describe the recruitment, screening, hiring, Academy, and OJT training processes and opportunities for improvement.

Recruitment and Initial Screening

Aware of the need to rapidly increase the number of hires it makes each year in order to properly staff facilities, FAA has been revamping its recruitment

___________________

4 ATO email of July 18, 2024, document #68 in material supplied by FAA and NATCA.

5 See https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/faa-hits-air-traffic-controller-hiring-goal.

6 This sentence was revised after release of the report to reflect the most current attrition estimates from FAA.

processes. The most significant change to date has been to open the recruitment (application) window for PE candidates to a year-round basis, which has increased the roughly 1,300 applicants in FY 2023 to 3,200 applicants in FY 2024. Since FY 2023 FAA has also offered two recruitment windows to move CTI candidates into the hiring process more quickly. FAA is also experimenting with keeping the recruitment window open longer in hopes of attracting a larger pool of well-qualified candidates. FAA has also made steps to expedite the initial screening process for eligibility, which currently takes 5–7 weeks.

With the aim to support facilities that have proven very difficult to staff, FAA has considered recruiting in the geographic area of these facilities as it has done in the past. As of the fall of FY 2024, FAA had no active plan to do this on a large scale. The only initiative the committee is aware of is FAA’s collaboration with Vaughn College, a CTI school in Queens, to encourage interest in the controller profession for candidates who might want to stay close to home and work at either the New York Center or TRACON, both of which are staffed more than 15% below their staffing standards.

The screening for medical clearance can take months. Candidates are seen initially by physicians in private practice who have been qualified for this purpose. Final approval is made by one of FAA’s medical experts. FAA would require additional medical professionals on its staff to expedite this approval process for applicants with issues in obtaining medical clearance. The sometimes-lengthy process for security clearances experienced by FAA is one that is shared throughout the government.

FAA’s Formal Screening Test for Controller KSAs

FAA is working to improve the ATSA screening test to reduce training failures by enhancing the initial selection process to better identify candidates with the highest potential for success in training, and in the challenging ATC role. Trainees who struggle with the required high level of cognitive ability, multitasking, and stress management aspects of the job are more likely to fail during training or voluntarily leave the workforce. The job’s psychological and physical demands can also contribute to training failures and departures. The rigorous training involves both classroom education and OJT, both of which are essential to develop and maintain safety and efficiency in ATC. The screening process should be designed to identify candidates who have a strong probability of success in training and weed out those early in the application process who do not. A consequence of a more discriminate screening tool may be that it will reduce the number of applicants who will score well qualified on the test. FAA would likely then need to (a) increase the current number of applicants who are eligible and

encouraged to take the aptitude test but do not, or (b) substantially expand the pool of applicants, or (c) both, to ensure that it has an adequate number of candidates who score as well qualified.

Background

In November 2016, FAA began relying on a revised ATSA test as a screening tool for ATC applicants. ATSA replaced FAA’s previous preemployment screening tool, the Air Traffic Selection and Training (AT-SAT) exam. As part of a review begun in 2012, FAA determined that the AT-SAT not adequately testing for skills and abilities for the then current job requirements. Moreover, the test questions and answers had been leaked to the public, rendering it ineffective (OIG 2023, 6–7).

To develop the revised ATSA, FAA hired a human resources (HR) firm to define the Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Other characteristics (KSAOs) required of controllers (OIG 2023, 7). FAA officials indicated to the committee these KSAOs include deductive and verbal reasoning, responsibility, achievement, memory (including remembering relationships), and visualizing.

Validation But Not Evaluation

According to the OIG (2023, 7–8) report, FAA relied on an expert HR firm to validate a new version of ATSA that was initially based on 15 elements. This validation included results from a random sample of 1,380 controllers who took the pilot test, supplemented with their supervisors’ assessments of them. The same version of ATSA was applied to 620 Academy students and the results were compared with the results of their final exam at the Academy. FAA then worked with the HR firm, the National Air Traffic Control Association (NATCA), and subject-matter experts to select 7 of 15 possible KSAOs that were judged to best represent those capabilities FAA believed it needed. The OIG report concluded that FAA used an appropriate process to validate the ATSA (OIG 2023).

The OIG (2023) report indicates that FAA had not evaluated whether the new ATSA was being successful in identifying promising candidates who would prove successful in the field. At the time of the OIG (2023) audit, an insufficient number of ATC specialists who had taken the revised ATSA since FY 2018 had reached CPC status to determine the effectiveness of the ATSA in screening for success as a controller.

ATSA Reassessment

Although the effectiveness of ATSA has not been demonstrated through evaluation, at the time of this writing in early 2025 the test is going through a “refresh” that will result in a new test battery and acronym for the test. Section 417 of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 required this reassessment of ATSA to begin within 180 days of enactment of the legislation (enacted May 16, 2024). Based on information provided to the committee, this process is expected to be completed by the end of FY 2026. After a new test battery has been developed, tested, and validated, FAA will need to ensure that it is evaluated for success in screening promising candidates for the FAA ATC workforce.

Academy and Facility Training Capacity

Principal ways to meet facility staffing targets are to hire more candidates (reviewed in Chapter 2), expand FAA’s training capacity, improve the Academy and facility training success rates, place candidates in Tracks where they are most likely to succeed, and place candidates in facilities that are most in need for them. Also important is the average time required to reach CPC status at a given facility as well as promoting and facilitating additional transfers from facilities staffed above the staffing standard ranges to facilities staffed below them. As noted in Chapter 2, the annual training capacity of the Academy is perceived to be about 1,800, but actual hiring (and hiring goals) throughout the post FY 2010 period was closer to 1,200 annually, which was partly due to external constraints on hiring. Thus, other than FY 2017 and 2018, the Academy was not routinely tasked by FAA to have enough subcontracted trainers at its 1,800-trainee capacity. The Academy even shut down for periods during the pandemic (OIG 2023) and let go of some of its subcontracted trainers during this period according to FAA officials who briefed the committee.

In FY 2023, ATO set a hiring goal (1,500) near the then training capacity of the Academy and facilities, many of whose training were still backlogged by training pauses during the pandemic.7 Hiring goals set in the FY 2024 Controller Workforce Plan then escalated to 1,800 for 2024, with expectations that they would grow to 2,400 by FY 2026 (FAA 2024). FAA is committed to expanding the capacity of the Academy; the agency received direction and authorization for funding an expansion of the Academy in Section 531 of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024.

Virtually all of the trainers at the Academy are former CPCs who work as subcontractors. In addition to the classroom training offered at

___________________

7 This sentence was revised after release of the report to clarify FAA’s training capacity in FY 2023.

the Academy, FAA officials indicated to the committee that about 150 of FAA’s 313 facilities have contracted with a company that subcontracts with former CPCs to provide classroom and simulator training. This relieves those facilities’ CPCs of this additional training duty. (Subcontracted former CPCs cannot provide training on position, which FAA refers to as OJT, because they are not employees and not current on current practice in the facilities in which they are training.) FAA also received direction and authorization to increase the number of former CPCs used as subcontractors for individual facility training in Section 530 of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024.

The main constraint on training capacity expansion, both at the Academy and individual facilities with training contractors, is the shortage of former CPCs willing to serve as contracted trainers. Almost 100% of the Academy’s trainers are former CPCs who have reached the age 56 limit on working as a CPC and virtually all those providing facility classroom and simulator training are as well. FAA reported to the committee in mid-2024 that its contractor for recruiting trainers is working diligently to attract and subcontract with more former CPCs as trainers, both at the Academy and individual facilities. Attracting former CPCs to work at Oklahoma City is a challenge. Some of the work is part-time and casual and many of the Academy’s trainers spend only enough weeks (sometimes months) at the Academy to teach their classes or lab sessions and then return home.

FAA is taking additional steps to accelerate training at the Academy and at individual facilities. ATO has been building and expanding the use of Tower Simulator Systems (TSSs) for several years; these simulators are reported to speed up the training process by 27% (FAA 2024). Congress required FAA to expand TSS capability to virtually all Tower facilities in Section 529 of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024. In November 2023, FAA committed to placing TSSs in 95 facilities by the end of 2025.8

As noted earlier in the discussion of CTI schools, the E-CTI program could increase the number of hires who can bypass the Academy altogether because of the training they receive in college and begin OJT at facilities immediately upon placement. The number of graduates is expected by FAA to remain small (FAA would hire about 25 per year) unless the number of CTI schools expands and more CTI schools commit to seeking enhanced status.

Placements in Facilities

ATO initially places most Terminal Track AGs in lower-level facilities (usually Levels 4–7) to improve their chances of achieving CPC status with an

___________________

8 See https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/faa-takes-actions-address-independent-safety-review-teams-recommendations.

expectation that some of them will later transfer to higher-level facilities. Table 6-1 summarizes the facility levels at which CPCs in the Terminal Track initially certify, whether as part of the GP or PE hiring pool.

Hires assigned to the Centers Track who graduate from the Academy are placed in higher-level Tracks by necessity since all Centers are designated as Level 10–12.

Summary

FAA’s recruitment efforts are garnering enough candidates for ATO to be selective (hiring 13% of all applicants). Gaining more recruits from the pool of former military and FAA controllers with experience would be helpful because of their higher success rates in training (described in the next section). Moving to year-round applications for this group in FY 2024 substantially increased applications, but even at the increased number of applicants in this pool it represented only 27% of all applicants.

A better screening test to winnow out candidates early who are less likely to succeed in training would reduce the wasted expenses and time spent on them but would likely also require FAA to recruit many more candidates since a larger share will not score well qualified. The ATSA is being revised again, and a new test is expected to be available by FY 2026. A concerted focus on defining the KSAOs that lead to success is critical. In addition to the planned validation of the new test, it would be helpful for FAA to evaluate the success of the tool in terms of reduced training losses.

The main constraint on training capacity at both the Academy and individual facilities is the shortage of former CPCs willing to serve as trainers. FAA appears to be searching for every available instructor it can find. The introduction of the E-CTI program increase the number of hires who would be able to skip the Academy because of the training they receive in college, but the number of graduates will remain small unless the number of CTI schools expands. FAA is rapidly expanding its use of simulators at the Academy and individual facilities, which is reported to reduce training times by 27% (FAA 2024, 11).

| Academy Graduates | Prior Experience | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity Levels | |||||||

| 4–7 | 8–9 | 10–12 | Total | 4–7 | 8–9 | 10–12 | Total |

| 2,266 | 597 | 232 | 3,095 | 1,461 | 535 | 235 | 2,231 |

| 73% | 19% | 7% | 100% | 65% | 24% | 11% | 100% |

TRAINING SUCCESS AND TIME TO CERTIFICATION

ATO’s stated goals are to certify controllers in the Terminal Track in 2.5 years or less and in the Centers Track in 3 years (FAA 2024, 49).9 This section provides a historical perspective on training success and average times to certification using the data file on all individual controllers since FY 2010 provided by FAA.

Hires Status FY 2010–2024

Training Failures and Successes

Table 6-2 provides a summary of the status of each hire for each FY since 2010 (the dates above each column represent the status of all controllers in that year, not the year of hire—many hired in previous years were still in training in FY 2020–2024). As can be seen, training failures at the Academy, which typically occur within a year of hire, rose from 7% in FY 2010 to a peak of 41% in FY 2017 and has since declined to 26% in FY 2024. Training failures at the Academy generally increase with hiring class size but not always. Note that Table 6-2 shows the status of hires in both the Terminal and Center Tracks. The status of those in each Track is shown in Appendix B.

The row titled “In Progress” in Table 6-2 shows the percentage of hires still in progress. Through FY 2015, all previous hires had either certified, failed, or left the unionized ATC workforce, either through promotion to a supervisory position, termination, retirement, or some other reason. The percentage still in process to first CPC certification (or failure to certify) increases rapidly in recent fiscal years because many have neither reached their first CPC certification nor failed.

Failures of DEVs (trainees seeking CPC status) in the “DEV Failure Rate” row has hovered between 11 and 4%, but a substantial percentage of hires are still in progress after FY 2020. Thus, the declining DEV failure rate over the entire 15-year period (6%) is partially attributable to the percentage of controllers still in progress toward certification who will likely fail but have not yet. The CPC success rate as shown in the row of the same name in Table 6-2 is also affected by the relatively high percentage of hires still in progress after FY 2020. Although FAA regularly cites time to CPC certification as roughly 2–3 years, the average time required to reach CPC status for Level 10–12 facilities has been increasing through FY 2019 as shown in Table 6-3.

___________________

9 Goals by level of terminal facilities are 1.5 years for Level 4–6, 2 years for Level 7–9, and 2.5 years for Level 10–12. The goal for Centers (all Level 10–12) is 3 years.

TABLE 6-2 Status of Hires FY 2010–2024 from Academy Training or Facility Placement

| Fiscal Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Failure Rate | 7% | 7% | 17% | 14% | 18% | 27% | 29% | 41% | 30% | 21% | 16% | 28% | 29% | 30% | 26% |

| In Progress | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 2% | 4% | 7% | 12% | 12% | 29% | 50% | 71% |

| DEV Failure Rate | 11% | 9% | 8% | 8% | 9% | 6% | 4% | 5% | 7% | 9% | 11% | 7% | 4% | 2% | 0% |

| CPC Success Rate | 81% | 82% | 74% | 77% | 71% | 65% | 63% | 51% | 56% | 61% | 57% | 50% | 37% | 18% | 2% |

TABLE 6-3 Average Time to First CPC Certification Across Facility Levelsa

| Facility Level | Fiscal Year | Grand Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2015 | 2019 | ||

| 4 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| 5 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| 6 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| 7 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| 8 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| 9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.7 |

| 10 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 3.0 |

| 11 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 3.2 |

| 12 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 3.3 |

| Grand Total | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 2.6 |

a This table was revised after release of the report to correct estimates of average time to first CPC certification across facility levels.

Note that the CPC training success as shown in Table 6-2 had fallen markedly from 81% in FY 2010 to 61% by FY 2019. (FY 2019 was picked as a year to feature because most trainees in progress had certified by that time.) It had fallen even farther for AGs by FY 2019 to 46% at Centers and 55% at Terminals. (Separate tables for these groups are shown in Appendix B.) Direct placements of controllers with previous experience (13% of hires FY 2010–2018) has partially counterbalanced these trends; they had an 81% CPC success rate by FY 2022 with only 11% still in progress.

Although time to move from DEV to CPC status after training begins has remained fairly constant for Facility Levels 4–9, it increased by 0.8 to 1.5 years in Level 10–12 facilities from FY 2010 to FY 2019 (see Table 6-3). Years after FY 2019 are not shown because there are hires still in progress for those years (see Table B-9 in Appendix B for all years between FY 2010 and 2019). Not only did the success rate of achieving initial CPC status decrease from 81% in FY 2010 to 61% in FY 2019 across all facility levels, but Level 10–12 facilities also experienced notable increases in the average years required to achieve CPC status after beginning training. As shown in Table 6-3, these increases ranged from 0.8 to 1.5 years, whereas other facility levels experienced minor upticks or declines. A more granular review of the Level 10–12 facility data for Centers and Terminals indicates that almost all the increase in training times at Level 10–12 facilities is

attributable to increases occurring at Centers, where average training times rose from 3.1 to 4.3 years. When adding the roughly 6 months that elapse between tentative hire offer and the beginning of training, the average amount of time that elapses from tentative hire offer to CPC status rose to at least 4.8 years. FAA’s National Training Initiative (NTI), discussed in the next section, may be improving these trends, but at the time of this writing in early 2025 it is too early to tell whether it will.10

A declining trend in CPC success rates has implications for future facility staffing, especially for higher-level Terminal facilities that partly depend on staff first certifying in Level 4–7 Towers and then transferring to higher-level facilities. According to the committee’s estimates, transfers from lower-level facilities into higher-level TRACONs, Towers, and “Up-Downs” (combined TRACON/Tower) are affected by three separate time periods (for FY 2018): (1) an average of 1.4 years to reach first CPC status, (2) an average interlude before transferring after first CPC certification of 1.9 years, and (3) an average of 1.6 years to certify at the higher-level facility. Thus, it takes an average of about 5 years to achieve a fully qualified controller at higher-level Terminals after training begins for those who transfer in from lower-level facilities. This trend has actually improved from an average of 6.5 years in FY 2010. Adding the typical 6- to 12-month range of tentative hires before entering training implies that achieving CPC status at Terminals involving a transfer requires roughly 5.5 to 6.5 years. As noted in Table 6-1, 65 to 73% of Terminal Track AGs are placed in Level 4–7 facilities initially; thus, the vast majority of these placements would require a transfer in order to reach a higher-level facility.

A total of 1,166 controllers have successfully followed this path over 15 years, producing an average of about 78 per year, which is a relatively small number compared to the average attrition at Terminals from retirements, resignations, removals, and deaths of roughly 400 per year, as estimated by the committee. Previously experienced hires who were initially placed and certified at a higher-level Terminal facility resulted in about 118 CPCs per year. Their average time to certification was much faster (roughly 2.5 years), and with an 80% success rate, demonstrating the benefit of previous experience in certifying to CPC. Although a promising pool of candidates from which to recruit, the overall size of previously experienced controllers is limited compared to those without experience, and FAA appears to be making considerable efforts to recruit and hire as many previously experienced candidates as possible.

___________________

10 This paragraph was revised after release to clarify the difference in CPC certification times between Level 10–12 Terminals and Centers.

National Training Initiative

FAA commissioned a group of former senior FAA officials and safety experts to review its activities and resources in FY 2022 in response to a series of close calls in the air and on runways (SRT 2023). Among its findings and recommendations, the SRT (2023, 22) indicated that the NTI was an important but underutilized ATO activity. Initiated in 2019, the NTI went into abeyance during the pandemic due to required pauses in training at the Academy and in facilities. FAA officials indicated to the committee that ATO is now fully committed to the NTI and acting when facility managers are not prioritizing training.

The NTI sets expectations for how many hours of training DEVs and CPC-ITs should be getting each week (SRT 2023). FAA closely monitors training progression at the facility level. FAA is collecting data on each trainee, monitoring training progression at facilities, and intervening when facilities are not progressing their trainees at appropriate rates. As reported to the committee in November 2024, together with NATCA, an NTI team of senior ATO and NATCA officials have intervened at several facilities and reoriented their training efforts, including by moving managers out who are not sufficiently prioritizing training. The committee supports the NTI and suggests that the NTI measure and monitor the end-to-end process efficiency, true throughput, and success rates, and continue to accelerate the rollout and use of tower training simulator systems to reduce training times.

It is important to note that CPC-ITs and DEVs generally train and qualify for each certification level at a facility, progressing through these levels until they are a fully qualified CPC. In the meantime, periodically the trainee will work on the original position(s) on which they are already qualified in order to maintain proficiency. If there is high workload, or if there are insufficient instructors (or due to other factors), a trainee may be asked to work positions on which they are already qualified in lieu of progressing through their training. In such a case, a trainee’s overall training duration from start to CPC may be prolonged. As shown in the previous chapter (see Table 5-1), the facilities for which CPCs represent a small share of facility controllers do not appear to have extended training durations to CPC in general. However, it could be an issue at some of the largest facilities as indicated by the increasing time required to achieve CPC status in Level 10–12 facilities. The NTI is meant to ensure that trainee progression is maintained. The committee supports an effort to get to the root cause of the growing failure rates in general and increasing time to certification at Level 10–12 facilities.

Summary

Two concerning trends are the declining average training success rate for CPCs and longer time to CPC certification at Level 10–12 facilities—by FY 2019 it had increased about 1.2 years to an average of about 4.3 years after training begins and at least 4.8 years on average after a tentative hire offer. Most of the increase in training time is occurring at Centers, where it increased from an average of about 3.1 to 4.3 years to at least 4.8 years after a tentative hire offer. In contrast, the training time for Level 4–9 facilities has improved from about 2.7 to about 2.1 years. Level 10–12 Terminals depend heavily on CPCs that transfer in from lower-level facilities. As of FY 2018 it was taking an average of about 4.5 to 5.5 years from a tentative hire offer for CPCs who are successful in training at Level 4–7 Terminals to transfer and then requalify at the higher-level Terminal. It is too early to determine whether the NTI has reversed these trends. The implication of these combined trends, if allowed to continue, is that the current shortage of CPCs at Level 10–12 facilities would require even more time to fill than in the past, even if a sufficient number of hires are made in upcoming years to ultimately achieve this goal. The NTI is a critically important initiative on FAA’s part, which it appears to be taking very seriously. It is essential that it continue to do so while finding ways to accelerate the time to certification and increase the success rates in training.

TRANSFERS AND STRENGTH MANAGEMENT

This section describes trends in transfers over time to examine transfers from lower to higher levels and transfers from facilities staffed above their staffing standard ranges to facilities below their staffing standard ranges. In both cases long-term trends are provided before and after FAA’s introduction in 2016 of a new process for managing transfers. FAA relies on voluntary transfers. With rare exceptions, it does not require them. There are considerable pay increases associated with transferring to higher-level facilities (discussed below), but the discussion that follows suggests that existing incentives and current management efforts alone are not enough to improve staffing levels at facilities staffed below their staffing standard ranges.

The National Centralized Employee Requested Reassignment (ERR) Process Team (NCEPT) established in FY 2016 manages transfers to fill CPC facility vacancies with ERRs.11 The NCEPT is a collaborative group that includes ATO and NATCA. It is the sole systemwide process for

___________________

11 Note that FAA published a report after the first year of implementation of this program: FAA. 2016. “ERR and NCEPT 2016 Program Report.” The committee is unaware of any subsequent ERR/NCEPT annual reports.

evaluating and approving/disapproving transfer requests. Note that there were roughly 700 ERRs per year for FY 2010–2024, almost two-thirds as many as those hired each year since 2010 (about 1,200 annually since FY 2010). Thus, transfers are second only to hires for facility strength management and are important for ensuring that CPCs end up at the facilities that most need them.

Transfers’ Role in Strength Management by Level of Facility

Table 6-4 compares transfers by facility complexity Level to examine whether transfers are meeting the intent of moving CPCs from lower to higher Levels to ultimately provide CPCs for the most important Terminal facilities with the most complex airspace. The first column summarizes all transfers from FY 2010–2024. The second two columns separate the time periods to before FY 2016 and after FY 2015 to capture the possible effects of NCEPT.

Given FAA’s goal to place AGs in low-level facilities to increase their chances of certifying as CPCs and then transfer to major Terminal facilities (Levels 10–12), only 46% of transfers moved up a Terminal Facility Level between FY 2010–2024. Most transfers (36%) remained at the same Level. The impact of the NCEPT process for managing transfers has slightly improved movements to higher-level facilities from 43% in FY 2015 to 47% in FY 2024, but the percentage is hardly different from FY 2010.

A well-functioning transfer policy would facilitate transfers from facilities that are above their staffing standard ranges to those that are below them. Yet, as shown in Table 6-5, over the entire FY 2010–2024 period, only 18% of transfers from facilities staffed more than 10% above their staffing standards have gone to facilities 10% below their staffing standard ranges. On an annual basis, these trends in transfers appear to improve after the NCEPT process was adopted in FY 2016. The share transferring out of facilities above their staffing standard ranges and transferring into facilities below their staffing standard ranges improves from 11% in FY 2016 to 20 to 25% after FY 2017, but the majority of controllers transferring from

TABLE 6-4 Share of Transfers Up and Down a Level, FY 2010, 2015, and 2024

| Transfer to Facility Level | FY 2010–2024 (%) | FY 2010–2015 (%) | FY 2016–2024 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Same | 39 | 43 | 36 |

| Higher | 46 | 43 | 47 |

| Lower | 16 | 14 | 15 |

| From AFN | >110% | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Transfer | FY | |||||||||||||||

| To AFN Fill Rate | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Grand Total |

| >110% | 73 | 128 | 161 | 196 | 220 | 126 | 94 | 142 | 58 | 45 | 69 | 45 | 29 | 73 | 59 | 1518 |

| 90% to 110% | 79 | 123 | 114 | 116 | 127 | 146 | 136 | 114 | 130 | 110 | 94 | 57 | 73 | 122 | 109 | 1650 |

| <90% | 76 | 46 | 36 | 54 | 43 | 46 | 28 | 30 | 63 | 59 | 51 | 31 | 36 | 50 | 54 | 703 |

| Grand Total | 228 | 297 | 311 | 366 | 390 | 318 | 258 | 286 | 251 | 214 | 214 | 133 | 138 | 245 | 222 | 3871 |

| From AFN | >110% | |||||||||||||||

| % Transfer | FY | |||||||||||||||

| To AFN Fill Rate | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Grand Total |

| >110% | 32% | 43% | 52% | 54% | 56% | 40% | 36% | 50% | 23% | 21% | 32% | 34% | 21% | 30% | 27% | 39% |

| 90% to 110% | 35% | 41% | 37% | 32% | 33% | 46% | 53% | 40% | 52% | 51% | 44% | 43% | 53% | 50% | 49% | 43% |

| <90% | 33% | 15% | 12% | 15% | 11% | 14% | 11% | 10% | 25% | 28% | 24% | 23% | 26% | 20% | 24% | 18% |

the facilities above their staffing standard ranges are transferring to those within or above their staffing standard ranges.

Role of Incentives in Transfers

As noted, FAA relies on voluntary transfers to help understaffed facilities improve their staffing levels. With rare exceptions, it does not require transfers. In this era of dual-income households, transfers that involve moving a household is a challenge. FAA relies on economic incentives in the pay structure to motivate movement of controllers to where they are most needed. This section describes the incentives to (a) move through the training process to CPC and (b) transfer to higher-level facilities.

Overall compensation levels for controllers are good given that the role does not require a college degree; they provide considerable incentives for controllers to progress through to full certification. FAA’s pay scales are independent of federal employees on the General Schedule. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median salary for all controllers in FY 2024 was $144,580.12 New hires at the Academy earn $45,800 annually while in initial training (as of January 1, 2024). Without accounting for locality pay (described next), trainees at a Level 7 Tower would gain a minimum increase of about $9,200 annually for each step from D1 to D2 to D3. CPCs at a Level 7 Tower (before locality pay adjustments) can earn between $82,500 and $111,400. These and other salary ranges discussed in this section do not account for overtime pay.

Locality pay adjustments are based on prevailing salaries in local labor markets; they are designed to help ensure that federal employee salaries are competitive with the private sector.13 However, they are not the same as cost-of-living adjustments.

For controllers, special locality pay rates apply in 58 geographic areas.14 For FY 2024, these adjustments exceed a 30% premium over the base rate in Alaska, Boston, Chicago, Hartford, Houston, New York-New Jersey metropolitan area, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, and the greater Washington, DC, area. The highest adjustment (45%) applies in San Francisco. For the rest of the country controllers at FAA facilities receive a 16.82% adjustment.15 Locality pay adjustments partly reflect cost of living which

___________________

12 See https://www.bls.gov/ooh/transportation-and-material-moving/air-traffic-controllers.htm.

13 See https://www.federalpay.org/articles/locality-pay.

14 Air Traffic Specialized Pay tables as of January 1, 2024. See https://www.faa.gov/jobs/working_here/benefits.

15 BLS makes an estimate for 58 metro statistical areas or states and then has an overall adjustment for the rest of the country, but the BLS overall adjustment differs from the one used for air traffic controllers.

affects salaries paid based on BLS surveys of labor markets, but the size of many of the local geographies for which adjustments are made means they may not correspond to the cost of housing within a reasonable commute of an ATC facility in the highest cost of living areas. For example, the locality pay map for the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area includes a wide swath of eastern New Jersey and southeastern Connecticut as well as New York City. The New York TRACON (N90) and Center (ZNY) are located on Long Island. JFK and LaGuardia Towers are located in Queens and Brooklyn, respectively. All are located in areas where traffic congestion is high throughout the day, meaning that affordable housing within a reasonable commute to these facilities, as well as their low training success rates, affects the willingness of CPCs at other facilities to move to them.

As an example of facilities with locality adjustments applied, in Albany the CPC salary at a Level 7 Tower would range from $99,200 to $134,000. In the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area, the range for a CPC at a Level 7 Tower would be $113,200 to $152,000. The incentives increase even more when moving to a higher-level facility. In the New York-New Jersey metro area, a CPC in a Level 12 facility would earn between $175,700 and $221,900; the latter figure being capped by the maximum pay possible under current law (P.L. 104-264[c]).

FAA has the authority to offer special incentives to attract staff to hard-to-staff facilities, such as covering moving expenses or offering housing allowances. The most exceptional example the committee is aware of is the effort by FAA to address the staffing shortages at the New York TRACON (N90). After many years of being unable to attract and retain sufficient staff at N90, FAA decided to move responsibility for approach control at Newark Airport to the Philadelphia Approach Control facility. After building a new approach facility in Philadelphia, and, following a protracted period of negotiation, FAA eventually mandated transfer of 17 senior controllers that included a $100,000 bonus to relocate temporarily or permanently to Philadelphia.16 (At the time, some controllers at N90 were reported by The New York Times to be working so much overtime to cover for inadequate staffing that they were making $400,000 a year.17 As noted in Chapter 3, it would be important for FAA to evaluate individual TOP at the shift level across the pay period in such high overtime situations to determine possible violations of fatigue rules and risks to safety.) Regarding other hard-to-staff facilities, such as those in California and southern Florida, FAA gives them priority for voluntary transfers but does not routinely offer transfer bonuses or cover the cost of moving. In applying incentives for transfers, FAA might

___________________

16 See https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/14/us/politics/air-traffic-controllers-job-relocation.html.

17 Ibid.

place an upper bound on what it would offer based on the marginal costs and benefits of transferring someone into a hard-to-staff facility compared to the cost of training a new hire to CPC status, as well as the extra overtime required during that duration at hard-to-staff facilities.

Potential Balancing of Existing Controllers Within the FY 2024 Workforce

Looking forward, the question arises about how much of the existing staffing at facilities below their staffing standard ranges could be addressed by existing staffing at facilities above their staffing standard ranges. To provide insight into this question, the number of Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs) who are in existing facilities that are 15% above the staffing standard is shown in Table 6-6. Being above 15%, the staffing standard range provides a smaller estimate of the potential transfers than from being 10% above of the staffing standard range, but it also avoids incorrect estimates of potential for transfers from small facilities such as Towers (average staff of 18). Consider a Tower facility that has 19 staff on board including 2 trainees in the pipeline to replace 2 CPCs that are expected to retire in the near future. If such a Tower had a staffing standard of 17, it would be rated as 12% over its staffing standard (19/17=1.12), but only temporarily. By using FTEs, the counts in Table 6-6 overestimate the number of CPCs available to transfer in the near future and also undercounts the number of trainees who will certify in the near future and be a candidate to transfer.

The first clear lesson to draw from Table 6-6 is that there are no FTEs in Centers above 15% of their staffing targets who could potentially transfer to the eight Centers staffed at 15% below their targets. (Not shown in Table 6-6 is that there also are no FTEs in Centers staffed between 110

TABLE 6-6 FTEs in Facilities Above and Below the AFN Staffing Standard, FY 2024

| Facility Type | Facilities Greater Than 15% Below Target | FTEs in Facilities Greater Than 15% Above Target |

|---|---|---|

| Center | 8 | 0 |

| Combined Control Facility | 4 | 0 |

| TRACON | 6 | 156 |

| Tower and Approach Control | 6 | 579 |

| Tower | 18 | 993 |

| Total | 42 | 1,728 |

| Total for Terminals Only | 30 | 1,728 |

and 115% of their staffing targets.) Transfers from the extra FTEs in the Terminal Track to Center Track occur much less often than remaining in the same Track, given the extra training required to gain the skills needed to work in Centers. Thus, for the most part, the only way to address shortages at Centers is to hire more in that Track and wait for an average of 4.5 to 5.5 more years for candidates to complete the Academy and OJT training required for them to certify to CPC status. This result indicates the importance of reducing the period of time throughout the hiring, training, and certification period described earlier in this chapter.

Combined Control Facilities have no surplus of FTEs either. Although they have Center-like functions, they also have Terminal functions and could draw from the surplus among FTEs in this Track, but since three of the four CCFs are located outside of the continental United States, gaining transfers from the continent has long proven challenging.

The story is different for FTEs in the Terminal Track. In FY 2024 there were 1,728 FTEs in this Track in facilities staffed at more than 15% of their targets and 30 facilities staffed 15% below their targets that could benefit from transfers. Given the challenges some transfers experience when attempting to certify in a higher-level facility, it is unlikely that all of these transfers would be able to certify in Level 10–12 Tower facilities upon transferring from a Level 4–7 Tower facility, but some, perhaps many, would.

Summary

Regarding appropriate facility staffing, transfers are second only to the number of new hires each year in staffing individual facilities to meet their staffing targets. Roughly 700 transfers occur each year, almost all of which are CPCs who require about 1.5 years on average to recertify after transfer (and not all succeed in certifying). Review of experience since FY 2010 in using transfers for facility strength management indicates that FAA is not being successful at encouraging transfers from overstaffed to understaffed facilities. This lack of success is partly attributable to FAA’s reliance on voluntary transfers. Apparently, it has proven difficult to encourage transfers into some of the critical facilities serving the National Airspace System that most need them. FAA has the authority to provide incentives to encourage more transfers out of overstaffed facilities to understaffed ones. Budget constraints may be an important reason why it has not used incentives more aggressively.

FAA RESPONSES TO NASEM 2014 REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee for the NASEM 2014 report made several recommendations on plan execution. This section focuses on the ones that have not been addressed, while acknowledging that others have been addressed to a considerable extent. According to briefings the committee received from FAA officials, the 2014 recommendations that have been largely responded to include Recommendations:

- 4-3 regarding the field staff’s understanding of FAA’s processes for estimating how facilities should be staffed;

- 4-5 regarding making clear to controllers their paths to success as a controller and supporting them in achieving this goal;

- 4-6 regarding having a strong mentoring program for junior controllers; and

- 4-8 regarding not overloading facilities with trainees when they have too few CPCs to provide OJT.

FAA has responded to the spirit of these recommendations. Two of the plan execution chapter recommendations from the 2014 report are addressed in other chapters of this report:

- 4-1 regarding use of the CPC-Equivalent Workforce concept as a more appropriate target for staffing models (not adopted) is covered in Chapter 5 of this report; and

- 4-9 regarding having an efficient shift scheduling tool (not successfully adopted) is addressed in Chapter 3.

The remainder of this section addresses inadequate responses to date to Recommendations 4-4 and 4-7.

2014 NASEM Report Recommendation 4-4

FAA should make more effective use of voluntary transfers to rebalance the workforce among facilities considered to have high staffing levels and those considered to have low levels, particularly where it can leverage controllers’ desire to transfer on the basis of hardship, career advancement, or personal circumstances. Such a strategic process would need to include the following:

- suitable incentives for transfers, developed and agreed on by FAA and NATCA, that would help rectify staffing imbalances, including establishment of a policy for resolving situations in which

- controllers who are willing to risk transferring to a higher-level facility fail to qualify into that facility; and

- systemwide processes and management of transfer requests to consider their impact on facility staffing, so that facilities with low staffing levels do not miss voluntary transfers claimed first by facilities with acceptable or high staffing levels.

As noted above, ATO has made some improvements, but it is not being effective in facilitating transfers to balance staffing levels across facilities. ATO has a process in place (NCEPT) to monitor and approve transfer requests in ways that are intended to serve facility staffing over individual preferences. They use the Priority Placement Tool, which has a variety of metrics of facility staffing and rank orders facilities in need of staff. However, as shown in the above analysis, NCEPT is only marginally improving the staffing levels of critically understaffed facilities. ATO has indicated that it has the authority to provide extra incentives when needed, subject to budget constraints, but, other than N90, it has not used these incentives aggressively.

2014 NASEM Report Recommendation 4-7

FAA should work with NATCA in developing and implementing special measures to address the concerns of hard-to-staff facilities. Such measures might include:

- incentives to transfer to and reside near the facility;

- selection processes and policies that would prescreen controllers willing to transfer to facilities and identify controllers likely to qualify (and not qualify);

- policies for reassignment of trainees who fail to qualify, to remove disincentives for potential applicants to the facility; and

- methods for training controllers at facilities one Level down in difficulty to nearly the Level required at the hard-to-staff facility, thus minimizing the training requirement once they are on site.

FAA has made extraordinary efforts to staff N90 (priority for transfers and transfer bonuses, among others) and continues to do so. Due to the difficulty recruiting staff to live near N90, FAA expanded the facilities at the Philadelphia Tower to handle the Newark traffic and has transferred some N90 staff to move there temporarily (with $100,000 bonuses). It has also made special efforts when Centers (e.g., Chicago [C90]) were going through periods of short staffing. The Oakland Center (ZOA) has also received ATO attention, though remains critically understaffed. As shown in Table 2-4,

at the end of FY 2024 ATO had about 22% of its facilities staffed at more than 15% below their staffing standards and 24% of its facilities staffed at more than 15% above their staffing standards. It has not used incentives aggressively to help rectify these imbalances in staffing.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Finding 6-1: To increase applicants and their strength as candidates, FAA has revised its hiring announcements for candidates with prior experience (now open year-round) and experimented with having two annual application windows for general public applicants and for graduates of E-CTI and regular CTI schools. FAA typically receives ample responses to its annual hiring announcement to the GP and CTI schools, which also result in the largest share of hires. The annual hiring window for controllers with previous experience has increased applicants from this pool of candidates.

Finding 6-2: FAA is revising and revalidating its initial screening tool (ATSA) for controller applicants as required by Congress. The goal should be to ensure that the applicants who progress through hiring are the best suited to succeed in Academy and OJT training, thus improving success rates and overall CPC production for a given class size.

Recommendation 6-1: After updating the ATSA, FAA should evaluate its effectiveness in screening for the types of individuals who can succeed in training.

Finding 6-3: FAA is expanding training capacity at the Academy and schools that participate in the E-CTI program. One challenge in expanding the Academy is attracting and retaining sufficient retired CPCs to serve as subcontracted trainers. The committee was told that many former CPCs are reluctant to go to Oklahoma City for a part-time job. FAA also relies on contracted former CPCs to conduct training at about 150 facilities; these subcontracted trainers can provide classroom training to relieve CPCs of this obligation. Another challenge is expanding graduates from E-CTI schools, who can bypass the Academy. In the near term, E-CTI graduates will be few in number (about 25 annually) and will remain so if the E-CTI program does not expand. FAA does not fund either the traditional CTI or E-CTI programs, thus the traditional CTI schools may be reluctant to expand training to allow them to qualify as E-CTI schools.

Recommendation 6-2: FAA should facilitate expansion of the number of E-CTI school graduates by whatever means are available to it, as these graduates can begin their training at individual facilities and shorten the period to certification.

Finding 6-4: The FAA Academy, though a critical—and for most—inescapable element in the path to becoming a CPC, currently plays no role in screening, hiring, or assigning candidates and trainees, despite being required to provide at least two stages of training and being expected to produce developmental controllers with a high chance of success in OJT. In addition, the Academy seems to be evaluated on how many hires it can take in, not on how many high-quality graduates it produces, contrary to some other training programs in aviation that focus on outcomes rather than inputs.

Recommendation 6-3: To improve the performance of the Academy, FAA should consider

- increasing the number of FAA instructors (versus subcontractors) given the role of FAA instructors in examining and qualifying trainees by moving from the FY 2024 level of 35 FAA instructors to the Academy’s requested 100 FAA instructors (or some other determined amount) including by changing assignment duration;

- integrating the Academy into both the screening and assignment processes;

- formalizing a feedback loop to the Academy from facility managers on the abilities of graduates placed in their facilities; and

- incentivizing and tracking higher throughput by giving the Academy targets on the number of high-quality DEVs it should produce annually per year, as well as by providing target success rates.

Finding 6-5: New hires are randomly assigned by FAA to either the Terminal or Centers Track at the point of hire without any assessment of their different capabilities for the tasks most pertinent to each Track. (This assignment is done to avoid jockeying during initial training by new hires for the Centers Track because Centers are all Level 10–12 facilities with higher pay scales than Level 4–7 Terminals that new hires in the Terminals Track are usually placed in.)

Recommendation 6-4: FAA should consider making track assignments further into the training process at a point when the Academy can contribute assessments about the tracks trainees would be best suited for.

Finding 6-6: FAA has committed to accelerate rollout of training simulators that are reported to have reduced training times by 27% and, through the NTI, FAA is providing management direction and accountability at the national level, and intervening when indicated, when facility managers are not giving training adequate priority.

Recommendation 6-5: FAA should continue to accelerate rollout and use of training simulators, keep abreast of innovations in other training technologies, and work to drive training efficiency up, and thus training duration down, by giving high priority to the NTI and continue to exercise accountability to facility managers who are not prioritizing training. Effective targets and metrics should be clearly understood at each facility.

Recommendation 6-6: Through its NTI effort FAA should continue to emphasize to facilities its recommended approaches to help trainees succeed and should measure the end-to-end process efficiency, true throughput, and success rates in order to factually assess the benefit of its efforts.

Finding 6-7: FAA is aware of the importance of improving the quality of training, both to reduce unnecessary training failures and to ensure that successes in training result in adequately trained CPCs. However, the agency has experienced (a) a precipitous decline in the average success rate of CPC-ITs at Level 10–12 facilities and (b) a sharp increase in training duration in its Level 10–12 En Route Centers from about 3.1 to about 4.3 years after training begins as of FY 2019 (the last year with complete data). Combining this average duration with a 6- to 12-month period from a tentative hire offer through medical and security clearance to beginning of training, the time period from a tentative hire offer to CPC status at Level 10–12 Centers averages at least 4.8 years. It is too early to know whether the NTI is reducing the number of years to certification at Level 10–12 facilities. If this duration is not shortened, it will result in at least an extra year before newly hired staff can progress to CPCs for service at these Level 10–12 major facilities. The renewed emphasis of the NTI should help in this regard.

Recommendation 6-7: FAA should determine the reasons why success rates for trainees becoming fully certified have been declining while training times have been increasing at Level 10–12 Centers and take deliberate actions to counter these trends.

Finding 6-8: FAA places the majority of candidates in the Terminal Track in lower-level facilities (Levels 4–7) to staff those facilities, and to reduce unnecessary training failures that can result from initial placement into higher-level facilities. FAA’s expectation is that some of these staff, once they reach CPC status, will transfer to a higher-level facility with a good chance of recertifying as a CPC. However, the transfer process to move the controllers who certify as CPCs at these Level 4–7 facilities is not successful in moving a sufficient number of them to higher-level facilities at the rates necessary to sufficiently staff the higher-level facilities. For those who do transfer to Level 10–12 facilities and certify, the process takes an average of 5.5 to 6.5 years from provisional hire offer to CPC status, in part due to the typical 1.9 years before transfer.

Finding 6-9: The NCEPT process has been only marginally successful at improving the transfer of CPCs from facilities staffed above their staffing standard ranges to facilities that are under their staffing standard ranges. In FY 2024, only 24% of transfers from facilities above their staffing standard ranges transferred to facilities below them.

Finding 6-10: In FY 2024 there were eight Centers staffed 15% below their staffing standards, but none more than 10% above, indicating that there is no surplus of FTEs at Centers who could transfer to those eight understaffed Centers. For Terminals, there was a pool of 1,728 FTEs at Terminal facilities staffed at more than 15% above their staffing standards who could potentially transfer to the 30 Terminals that are staffed at 15% below their staffing standards.

Recommendation 6-8: If ATO continues to rely on voluntary transfers for facility strength management, FAA should introduce additional incentives for CPCs working at facilities with more than enough staff to transfer to those that do not have enough staff. The incentives should be designed to favor the Level 10–12 facilities that have an outsized impact on commercial operations in the National Airspace System. Congress should provide FAA with the added resources needed for such an incentive program.

REFERENCES

FAA (Federal Aviation Administration). 2016. “Employee Requested Reassignment (ERR) and National Centralized Process Team (NCEPT) FY 2016 Program Report.” U.S. Department of Transportation.

FAA. 2024. “Air Traffic Controller Workforce Plan: 2024–2033.” U.S. Department of Transportation.

OIG (U.S. Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General). 2023. “FAA Has Taken Steps to Validate its Air Traffic Skills Assessment Test but Lacks a Plan to Evaluate its Effectiveness.” Report AV2023011. U.S. Department of Transportation, January.

SRT (Safety Review Team). 2023. “National Airspace System Safety Review Team: Discussion and Recommendations to Address Risk in the National Airspace System.” Federal Aviation Administration, November.