Practices for Collecting, Managing, and Using Light Detection and Ranging Data (2025)

Chapter: 3 Data

CHAPTER 3

Data

The utilization of Lidar technology has transformed 3D geospatial data collection and management processes, particularly in transportation and environmental monitoring contexts (Olsen et al. 2013). Yen (2011) highlighted the potential of vehicle-mounted mobile Lidar systems to address challenges faced by state DOTs, such as decentralized data collection and increased costs. Their study underscores the feasibility and benefits of mobile Lidar for the Washington State Department of Transportation, emphasizing cost savings, improved efficiency, and enhanced worker safety. However, implementation hurdles such as funding and data integration need to be overcome for effective utilization of this technology. O’Hara (2011) delves into advancements in aerial Lidar technologies in the United States, emphasizing the role of standardized guidelines and specifications set by organizations like the U.S. Geological Survey National Geospatial Program in ensuring data accuracy. The article also highlights the pivotal role of governmental funding initiatives, such as the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act, in bolstering Lidar mapping projects nationwide.

Further elaborating on data management aspects, Spore and Brodie (2016) present a comprehensive data management plan (DMP) for remote sensing datasets at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center’s Coastal and Hydraulics Laboratory Field Research Facility. This plan delineates the stewardship and integration framework for various datasets, including mobile and stationary Lidar data, X-band radar, and imagery. Emphasizing phases of data collection and stewardship, the DMP underscores the importance of documentation, sharing, storage, and protection of Lidar datasets to facilitate their integration with other programs and stakeholders. The reviewed literature underscores the transformative potential of Lidar technology in enhancing geospatial data collection, management, and utilization across diverse applications. Standardization efforts, funding initiatives, and robust data management frameworks are pivotal for maximizing the benefits of Lidar throughout its life cycle.

Lidar Data Life Cycle

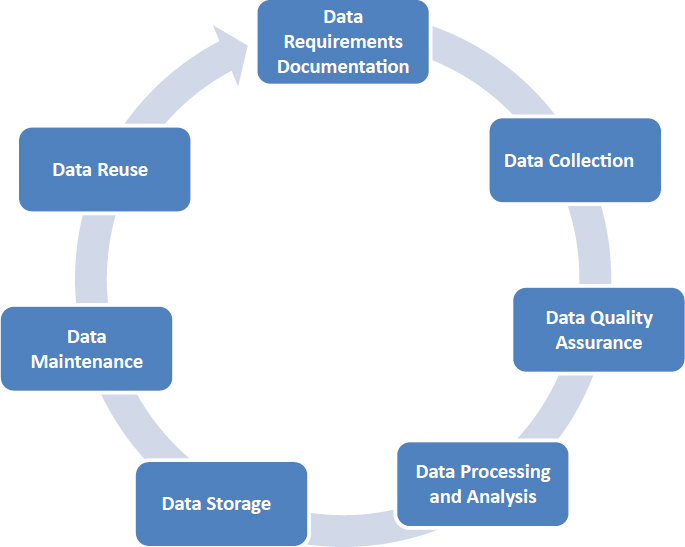

The Lidar data life cycle comprises a series of major stages that ensure the effectiveness, accuracy, and utility of the data throughout its use. As shown in Figure 2, this life cycle includes detailed phases such as data requirements documentation, collection, processing, storage, maintenance, and potential reuse. Each of these stages plays an essential role in the management and application of Lidar data, and understanding their significance is needed for maximizing the data’s value across various sectors including urban planning, environmental monitoring, and infrastructure management. A detailed plan for Lidar data management can be found in Olsen et al. (2013). Additionally, several NCHRP reports provide detailed guidance on general management: NCHRP Synthesis 508: Data Management and Governance Practices (Gharaibeh et al. 2017); NCHRP Web-Only Document 282: Framework for Managing Data from Emerging Transportation Technologies to

Support Decision-Making (Pecheux et al. 2020b); NCHRP Report 666: Target-Setting Methods and Data Management to Support Performance-Based Resource Allocation by Transportation Agencies (Cambridge Systematics 2010); and NCHRP Research Report 952: Guidebook for Managing Data from Emerging Technologies for Transportation (Pecheux et al. 2020a). These resources collectively offer insights into managing data effectively that are applicable to the governance and utilization of Lidar data in transportation systems. Also relevant is NCHRP Project 20-44(48), “Peer Exchanges on Data Management and Governance Practices,” work on which is currently underway (https://apps.trb.org/cmsfeed/TRBNetProjectDisplay.asp?ProjectID=5415).

Data Requirements Documentation

The Lidar data life cycle commences with a major step: the thorough documentation of data requirements. This initial stage sets the foundation for all subsequent activities by clearly defining what the collected data needs to accomplish. It involves a detailed assessment of the project’s specific needs and objectives, which guides the entire data collection and utilization process. During this phase, stakeholders and data managers collaborate to pinpoint the characteristics of the data required for the project. This includes determining

- The resolution, which dictates the level of detail that the Lidar data must capture;

- Accuracy, which affects the reliability of the data for making precise measurements; and

- Coverage, which ensures that the data encompasses all necessary geographic areas.

By establishing these parameters upfront, teams can avoid the collection of extra data, thereby optimizing resources and focusing efforts on gathering only what is truly needed for the project’s goals.

Proper documentation of these requirements is pivotal. It not only directs the choice of suitable Lidar systems and configurations but also influences the planning of the data collection phase, ensuring that the methods and technologies employed are best suited to meet the established criteria. For instance, if a project requires high-resolution data for detailed terrain analysis, the

documentation will specify this requirement, guiding the selection of appropriate Lidar technology that can provide the necessary detail level. Moreover, comprehensive data requirements documentation helps align the project team’s efforts with the intended use of the data, which enhances overall project efficiency. It serves as a reference point throughout the life cycle, helping to maintain focus and ensuring that all activities contribute toward fulfilling the documented objectives.

This stage is about creating a blueprint for the data collection efforts. It ensures that every step taken in the life cycle of Lidar data is purposeful and efficient, minimizing resource wastage and enhancing the potential for the successful application of the data in meeting the project’s goals. By laying down clear, well-documented requirements, organizations can significantly improve the effectiveness and efficiency of their Lidar-based projects.

Data Collection

In the data collection phase of the Lidar data life cycle, a single Lidar system or multiple ones—airborne, terrestrial, or mobile—are actively deployed to capture spatial data from the targeted environment. This stage is fundamental because the quality of data collected influences all subsequent operations in the data life cycle, influencing the processing, analysis, and ultimate long-term usability of the data. During this phase, meticulous planning can ensure that the deployment of Lidar systems is optimized for the environment and project requirements outlined in the Data Requirements Documentation. The choice of technology—whether to use an airborne system capable of covering vast areas quickly or a mobile system for detailed street-level mapping—depends on the specific needs of the project. As it was reviewed in this chapter, each type of system offers different strengths and capabilities, and selecting the appropriate one is important to achieving the desired data quality and coverage.

For example, if the project requires high-resolution topographic information on a rugged terrain, airborne Lidar might be chosen for its ability to capture large swaths of terrain quickly and from a safe distance (Shan 2018). Alternatively, if the focus is on urban planning where detailed measurements of buildings and infrastructures are needed, terrestrial or mobile Lidar systems would be more appropriate because of their precision at close range. Furthermore, the actual data collection process must be carefully managed to ensure that the Lidar systems operate at peak efficiency and that data is consistently collected. This involves calibration of the equipment to suit specific environmental conditions, such as adjusting for atmospheric variables in airborne Lidar or navigating around obstacles in urban areas with mobile Lidar. Ultimately, the success of this phase hinges on a well-coordinated effort that aligns advanced technological deployment with strategic planning based on thorough initial documentation. By carefully managing the data collection phase, teams can significantly enhance the quality and relevance of the Lidar data, which is important for supporting all subsequent phases of the life cycle and ensuring the data’s applicability to the project’s goals and other uses.

In addition to data collected directly by state DOTs, this report also examines Lidar data from various non-DOT sources, which have become increasingly significant in recent years. These sources include:

- Connected Vehicle and Autonomous Vehicle (AV) Data: Data collected from connected and autonomous vehicles is rapidly becoming an important resource for transportation planning and operations. This data includes real-time information on vehicle positions, speeds, and other metrics that can be integrated with Lidar data to enhance situational awareness and decision-making (DriveOhio n.d.).

- Survey Vendor Pipelines: Numerous private vendors offer Lidar data collection services, providing high-resolution datasets for various applications. These vendors use advanced technologies and methodologies to ensure data accuracy and coverage, supporting DOTs in areas where in-house capabilities may be limited.

- HD Mapping: HD mapping involves creating highly detailed maps that include precise information on road geometry, lane markings, and other important features. HD maps support autonomous vehicles and can be used in conjunction with Lidar data to improve navigation and safety systems (Bao 2023).

The integration of data from these varied sources enriches the overall dataset available to DOTs, offering new opportunities for analysis and application in transportation projects.

Data Quality Control and Assurance

Ensuring the accuracy and reliability of Lidar data throughout its life cycle is vital for its effective use in any transportation application. Data QA encompasses a plan to implement processes and practices designed to validate and maintain the integrity of Lidar data at every stage—from collection through storage. QC consists of the procedures implemented to directly verify the data meets the desired specifications. Calibration of Lidar systems is a foundational QA practice that must be conducted before and during data collection. This involves verification (and sometimes adjustment) of the Lidar instruments to ensure that their readings are accurate and consistent with baseline measurements. Regular calibration helps in reducing systematic errors that could affect the entire dataset.

Several DOTs have created checklists or guidelines to help with the verification of Lidar data delivery products. The Department of Transport and Main Roads, Queensland, Australia (2023a), for example, has developed a detailed checklist to support the QC process as well as document relevant metadata (Table 4). In conjunction with the checklist, they have developed automated tools to verify the completeness of delivered Lidar datasets following a systematic naming convention.

Validation against known “ground truth” measurements is another main component of data QC (Olsen et al. 2013; Nolan et al. 2015; 2017; ASPRS 2024) to verify the accuracy of the Lidar data, especially in applications requiring high levels of precision. By comparing the Lidar data with high-precision direct measurements taken on the ground, validation helps to confirm that the data accurately represents the physical characteristics it purports to measure. Periodic reviews of the stored Lidar data are necessary to ensure that it continues to maintain its integrity over time. Regular audits and integrity checks can help in identifying potential issues early, allowing for timely corrections and ensuring that the data remains reliable for future use.

The American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (ASPRS) has released updated positional accuracy standards for digital geospatial data (ASPRS 2024; Abdulla 2023). These detailed standards describe statistical procedures to report the accuracy of geospatial data products. The standards require obtaining a minimum of 30 and maximum of 120 check points, depending on project size; reporting of accuracy as the root mean square differences between the check points and product; and reporting of the check point accuracy given that the Lidar data accuracy can be similar to the check point accuracy. The standard also provides additional QC measures such as Lidar relative swath-to-swath precision, minimum nominal pulse density, and spatial distribution of check points. In addition to requirements and QC procedures and metrics, the standard provides terms and definitions, mathematical and statistical background, and examples for different types of geospatial data products.

Implementing robust QA protocols that standardize the QA processes across all phases of the Lidar data life cycle is important. These protocols include detailed documentation of QA procedures, training for personnel involved in data handling, and the use of advanced software tools designed to automate parts of QC processes, such as anomaly detection and error logging. By focusing on comprehensive QA measures, organizations can greatly enhance the reliability of their Lidar data. This not only boosts confidence in the data used for important decision-making but also enhances the overall value of the data, supporting its use in a wider range of applications.

Table 4. Sample Mobile Laser Scanning (MLS) deliverables checklist (© The State of Queensland, Dept. of Transport and Main Roads, 2023. Used with permission under CC BY 4.0).

| Department of Transport and Main Roads | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Laser Scanning Technical Guideline Checklist | Project Number: | |

| Date: | Transport and Main Roads | Offeror |

| General | ||

| PRFMs | ||

| Project Reference Frame Mark (PRFM / SPRFM) spacing (km) | ||

| Number of concurrent GNSS Base Stations used for processing each Point cloud | ||

| GNSS Baseline Processing method (PRFM Base Station to MLS Vehicle) | ||

| Baseline lengths i.e. from Base Station to MLS Vehicle (km) | ||

| Coloring of Point Clouds | ||

| MLS Variables (Refer to Section 9 of the TMR MLS Technical Guideline) | ||

| Coloring of Point clouds has been addressed | ||

| Detailed methodology to eliminate shadowing has been presented | ||

| Density and Pattern diagrams have been supplied for each configuration proposed | ||

| Number of Independent MLS Vehicle Passes | ||

| Imagery photo-point capture intervals (ie every (x) m along the road) | ||

| Imagery Resolution | ||

| MCPPC (Refer to Section 11 of the TMR MLS Technical Guideline) | ||

| Uncertainties (Horizontal) | ||

| Horizontal Survey Uncertainty (x) mm | ||

| Horizontal Relative Uncertainty (y) mm | ||

| Horizontal Relative Uncertainty (yy) ppm | ||

| Uncertainties (Vertical) | ||

| Vertical Survey Uncertainty (z) mm | ||

| Vertical Relative Uncertainty (zz) mm | ||

| Vertical Relative Uncertainty (zzz) ppm | ||

| PPC (Refer to Section 12 of the TMR MLS Technical Guideline) | ||

| Uncertainties (Horizontal) | ||

| Horizontal Survey Uncertainty (x) mm | ||

| Horizontal Relative Uncertainty (y) mm | ||

| Horizontal Relative Uncertainty (yy) ppm | ||

| Uncertainties (Vertical) | ||

| Vertical Long sections | ||

| Vertical Survey Uncertainty (z) mm | ||

| Vertical Relative Uncertainty (zz) mm | ||

| Vertical Relative Uncertainty (zzz) ppm | ||

| GC Targets and QA | ||

| Ground Control Targeting Required | ||

| Ground Control Targets (Horizontal) | ||

| Targeting Coordination Method | ||

| Ground Control Target Spacing | ||

| Ground Control Targets (Vertical) | ||

| Targeting Coordination Method | ||

| Ground Control Target Spacing | ||

| Department of Transport and Main Roads | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Laser Scanning Technical Guideline Checklist | Project Number: | |

| Date: | Transport and Main Roads | Offeror |

| General | ||

| QA Check Points Required (Refer to Appendix F of the TMR MLS Technical Guideline) | ||

| Check Points and Sites (Horizontal) | ||

| Horizontal - Survey and Relative Uncertainty Check Points and Site Methodology | ||

| Horizontal Survey Uncertainty Check Point Spacing (Refer to Appendix A and F) | ||

| Horizontal Relative Uncertainty Check Site Spacing (Refer to Appendix B and F) | ||

| Check Points and Sites (Vertical) | ||

| Vertical - Survey and Relative Uncertainty Check Points and Site Methodology | ||

| Vertical Survey Uncertainty Check Point Spacing (Refer to Appendix C and F) | ||

| Vertical Relative Uncertainty Check Site Spacing (Refer to Appendix D and F) | ||

| POINTCLOUD (General Specifications) (Refer to Section 11 of the TMR MLS Technical Guideline) | ||

| Useful range statement: The MCPPC or PPC supplied meets or exceeds the accuracy requirements for this project | ||

| Pointcloud Cleansing | ||

| Type/Method of Pointcloud Cleansing | ||

| Pointcloud Thinning | ||

| Type/Method of Pointcloud Thinning | ||

| Pointcloud Classification | ||

| Type/Method of Pointcloud Classification | ||

| Las version | ||

| GFM | ||

| Uncertainties (Horizontal) | ||

| Horizontal Survey Uncertainty (x) mm | ||

| Horizontal Relative Uncertainty (y) mm | ||

| Horizontal Relative Uncertainty (yy) ppm | ||

| Uncertainties (Vertical) | ||

| Vertical Survey Uncertainty (z) mm | ||

| Vertical Relative Uncertainty (zz) mm | ||

| Vertical Relative Uncertainty (zzz) ppm | ||

| GFM Extraction (Refer to Section 13 of the TMR MLS Technical Guideline) | ||

| GFM Extraction from the | ||

| GFM Points conform to PPC (or MCPPC) Uncertainties | ||

| GFM Extractions Required For: | ||

| Pavement | ||

| Description of Deliverable | ||

| Extraction Intervals Cross Sectional (X) m | ||

| Extraction Intervals Longitudinal (Y) m | ||

| Line marking | ||

| Description of Deliverable | ||

| Extraction Intervals Longitudinal (Y) m | ||

| Barrier device Strings | ||

| Description of Deliverable | ||

| Extraction Intervals Cross Sectional (X) m | ||

| Extraction Intervals Longitudinal (Y) m | ||

| Department of Transport and Main Roads | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Laser Scanning Technical Guideline Checklist | Project Number: | |

| Date: | Transport and Main Roads | Offeror |

| General | ||

| Road Signage | ||

| Description of Deliverable | ||

| Features and Services | ||

| Description of Deliverable | ||

| Extraction Intervals Cross Sectional (X) m | ||

| Extraction Intervals Longitudinal (Y) m | ||

| Structures | ||

| Description of Deliverable | ||

| Extraction Intervals Cross Sectional (X) m | ||

| Extraction Intervals Longitudinal (Y) m | ||

| Terrain | ||

| Description of Deliverable | ||

| Extraction Intervals Cross Sectional (X) m | ||

| Extraction Intervals Longitudinal (Y) m | ||

Data Processing and Analysis

Once collected, Lidar data undergoes several transformations during the data processing phase (Olsen et al. 2013). This stage can refine the raw data into a format that is not only usable but also reliable and accurate for analysis and decision-making. The processing of Lidar data includes several key tasks: noise reduction to clear any extraneous data captured that do not represent surface reflections; georeferencing to reference data into a common coordinate system; classification to categorize the data points based on geometric, color, intensity, or other information; and the transformation of these points into formats that are compatible with GIS, computer-assisted drafting, or BIM applications. This phase is highly technical and utilizes advanced software and algorithms designed specifically for Lidar data.

Noise reduction is necessary as Lidar sensors can pick up unwanted signals from particles in the air or incidental reflections, which if not removed, can distort the final data output. Effective noise reduction ensures that the data represents an accurate depiction of the physical environment (Charron 2018).

Georeferencing includes steps to (1) compute 3D location information from the raw sensor data consisting of angles and distances combined with sensor calibration information, (2) compute transforms to a common global coordinate system using GNSS information for the trajectory, scanner location, and/or transformation control points, and (3) minimize errors between overlapping scans, flightlines, or passes through a rigorous adjustment process (Nolan et al. 2015; 2017).

Classification involves assigning each data point in the Lidar dataset to a category based on its characteristics. For example, points may be classified into categories such as ground, vegetation, buildings, and water. This step is necessary for subsequent applications such as creating a DEM or other interpretations that rely on understanding the landscape’s composition. Che, Jung, and Olsen (2019) provide a detailed overview classification, extraction, and object recognition techniques of mobile Lidar data.

The transformation of data into usable formats involves converting the Lidar measurements into digital files that can be easily accessed, shared, and integrated into existing systems for further analysis (Olsen et al. 2013). This might include rasterization, where point clouds are

converted into a more manageable raster format, or vectorization, which might be used for creating line drawings of features detected by the Lidar.

The effectiveness of the data processing stage can significantly influence the overall success of Lidar-based projects. It requires a combination of powerful computing resources, sophisticated software, and expert knowledge in data handling and geospatial analysis. By ensuring the integrity and usability of the data at this stage, organizations can leverage Lidar technology to its fullest potential, supporting robust decision-making processes and innovative applications across various fields.

Data Storage

After processing, the storage of Lidar data step in the data life cycle consists of securely housing the data in robust and scalable storage solutions (Yen et al. 2011). Proper storage not only preserves the integrity and usability of the data but also facilitates efficient access and retrieval. This stage is important for the long-term utility and maintenance of Lidar data to support a variety of applications. Effective storage solutions for Lidar data include cloud storage, servers, and external hard drives. Each of these storage options offers different benefits in terms of capacity, scalability, and accessibility. Cloud storage is particularly advantageous for its scalability and ease of access from multiple locations, making it ideal for collaborative projects. Servers, whether onsite or virtual, provide robust data management capabilities, while hard drives offer a more traditional, physical storage solution that can be useful for archiving.

An integral part of data storage is the inclusion of comprehensive metadata, which details the data’s origin, quality, collection conditions, and processing history. Metadata is defined as “data about data,” and helps ensure that the data remains accessible and interpretable over time (Riley 2017). It provides users with the context to understand how and why the data was collected and processed, assess its suitability for specific applications, and integrate it with other datasets effectively. Incorporating metadata also aids in the systematic organization of data within storage systems. It allows for efficient searching and retrieval based on specific attributes such as collection date, geographic location, or data quality. This capability enables effective management of large volumes of Lidar data and supports complex analyses involving multiple data sources.

By implementing robust data storage practices, inclusive of detailed metadata, and utilizing modern storage technologies such as cloud platforms, servers, and hard drives, organizations can maximize the longevity and utility of their Lidar data. This approach ensures that Lidar data is not only preserved in a secure and structured manner but also remains readily usable for ongoing and future projects, thereby enhancing the overall value of the data collected.

Data Maintenance

Data maintenance encompasses the upkeep and continual relevance of stored data through regular checks and updates to ensure that the data remains accurate and reflects current conditions. Environments and landscapes can change over time because of natural events, construction, or other alterations, rendering the originally captured data potentially outdated or incorrect. Effective maintenance practices include routine audits of the data to identify and correct any inaccuracies or anomalies that might have emerged since the data was last used or updated. This process can require re-alignment of the data with new ground truth measurements or integration of recent data from follow-up surveys to ensure continuity and accuracy. Additionally, updating the data to reflect changes in the landscape or built environment is vital for applications in urban planning, environmental monitoring, and infrastructure management,

where the precision of the data can significantly impact decision-making and project outcomes. For instance, after major construction projects or natural disasters, Lidar datasets may need substantial updates to accurately represent the new state of the area (Singh 2008).

Data maintenance also involves correcting any errors that might have been overlooked during the data processing stage or have been introduced by subsequent data manipulations. Regularly addressing these issues helps maintain the integrity of the data and extends its usefulness for future analyses. Implementing robust data maintenance practices not only helps preserve the value of the Lidar data over time but also ensures it remains a reliable resource for ongoing projects and longitudinal studies. By keeping the data current and accurate, organizations can continue to rely on it for critical analyses and decision-making processes, maximizing the ROI in Lidar technology.

Data Reuse

The final stage of the Lidar data life cycle, data reuse, involves leveraging previously collected and processed data for applications beyond its initial intended purpose. The common adage with Lidar data is “collect once; use many.” This stage can help maximize the ROI in Lidar technology, as it extends the utility of the data across various domains and projects. Reusing Lidar data can significantly enhance efficiency and resource utilization within and across organizations by avoiding the costs and time associated with new data collection efforts. The data collected must be of sufficient accuracy and quality to be applicable and beneficial for reuse in various contexts (Olsen et al. 2013).

One of the most compelling aspects of data reuse is the opportunity to support diverse applications such as change detection, where Lidar data collected over time can be analyzed to identify and quantify changes in the environment. This is particularly valuable in many transportation applications such as planning, slope stability analysis, hydrological studies, pavement degradation, and asset condition assessment. For example, comparing historical Lidar datasets with recent ones allows researchers and planners to observe how road assets evolve, providing important insights for planning. The accuracy of the collected Lidar data must be rigorously defined and maintained to ensure it meets the standards required for these varied applications.

Furthermore, making Lidar data available for reuse encourages collaboration between different sectors and disciplines. Universities, government agencies, and private companies can all benefit from accessing a shared pool of Lidar data, which can be applied to new research questions or integrated into broader studies examining a range of factors, including transportation infrastructure efficiency. Ensuring the data is accurate enough to be shared and used by other parts and sections of the DOTs is necessary to foster such collaborations. Having a broad pool of personnel using the data can help identify and promptly resolve any issues in the data (Olsen et al. 2013).

By promoting the reuse of Lidar data, organizations not only amplify the data’s value but also contribute to a more sustainable approach to data management. This practice supports the development of more comprehensive and multi-dimensional analyses and fosters innovation by providing a rich dataset for exploring new possibilities. Accurate and high-quality Lidar data is fundamental to the success of these initiatives, ensuring that the reused data remains reliable and valuable across various applications.

Data Management and Governance Practices

The management and governance of Lidar data have evolved significantly, with advancements in data management systems that accommodate the complexity and volume of Lidar datasets. The progression from traditional database management techniques to more sophisticated systems has been marked by several notable research contributions over the years (Arshad 2016;

Graham 2017). The early exploration of Lidar data management was presented by Liu et al. (2008), who developed a methodology utilizing an octree partitioning scheme combined with local KD-trees to manage and visualize dense Lidar point cloud data effectively. Their approach focused on optimizing data display speeds and addressing the challenges associated with very dense datasets, providing a foundational framework for subsequent developments in Lidar data management.

Continuing this development, Lewis, McElhinney, and McCarthy (2012) expanded the application of database management systems to handle high-resolution Lidar data. Their research focused on constructing a comprehensive Lidar data pipeline within a spatial database framework. This included populating the database, creating a spatial hierarchy, and segmenting data based on user requirements, all managed through an efficient WebGL-enabled viewer. This integrated approach facilitated enhanced management of large volumes of Lidar data, paving the way for more advanced data handling techniques. Schuetz (2016) developed a transformative approach and open-source platform, Potree, to efficiently stream, render, and share point cloud data in the cloud. Potree creates and stores multiple subsampled versions of datasets for interactive display through WebGL. Given its efficiency in visualizing massive point cloud datasets, the Potree framework has been adopted and integrated into multiple Lidar processing software packages and online data-sharing platforms. Potree can also be integrated with advanced data organization and tiling schemes such as the open platform, Cesium. Lastly, Vo et al. (2019) introduced a novel Lidar point cloud data encoding solution compatible with the Hadoop distributed computing environment. Their work focused on optimizing data storage and processing efficiency, demonstrating significant reductions in data volume and querying times. This research emphasized the importance of innovative data encoding and distributed storage solutions in managing the increasing scales of Lidar data.

Advancements in the field were further demonstrated by Fernandez-Diaz and Cohen (2020), who reprocessed historical Lidar data using contemporary software to improve the resolution and fidelity of topographic mapping. Their work not only enhanced the understanding of geographic features but also addressed issues related to data management, access, and ethical use in geospatial research, highlighting the importance of robust data governance practices. In more recent developments, Lokugam Hewage et al. (2022) reviewed state-of-the-art point cloud data management (PCDM) systems, focusing on the scalability and performance of various parallel architectures and data models. Their comprehensive evaluation of shared-memory, shared-disk, and shared-nothing architectures, along with relational and novel data models, provided strategic insights into selecting appropriate technologies for scalable and efficient PCDM system development. These contributions show the ongoing need for agile, efficient, and robust data management systems to keep pace with the advancements in Lidar technology and the increasing complexity of geospatial data challenges.

Data Formats

Data formats can vary substantially depending on vendor, platform, and system. Most scanners provide data in a proprietary format which is then converted into another proprietary database format when imported into vendor software. To facilitate data exchange, there are three main open-source formats used widely in the community for data sharing.

- ASPRS LAS/LAZ. (ASPRS 2023). This format is widely used for airborne and mobile Lidar systems. It contains detailed header information and contains several point record formats based on the data attributes that are collected. It provides “extra bytes” to allow users to define custom attributes in a systematic way that can be read by other packages. LAZ is a compressed

- version of the LAS format developed by Martin Isenburg that typically reduces the file size by a factor of 8.

- ASTM E57. (Huber 2011). The ASTM E57 data exchange format is widely used for terrestrial laser scanning and imaging systems. This format enables the data to be stored in a structured format (e.g., in the scanlines from the acquisition pattern), which enables highly efficient data processing. It also stores the photographic images with the point cloud data and the associated transforms to enable software to simultaneously exploit both forms of data.

- HD5. (Bertini 2023). The HD5 format is not currently implemented in many vendor software packages. However, it is being used in many data science and ML applications. It has also gained a lot of traction within government agencies. The HD5 is a flexible format to manage and organize complex data. It can store and link many types of data (e.g., point cloud data, text annotations, and photographs) within a single file.

Many other open-source formats have been utilized over the years, including ply, ptx, xyz, ptx, txt, and pcd. However, many of these formats were developed before the standardized formats and generally have been phased out by the industry. ASCII text or csv files are still sometimes used for data sharing but are not recommended given their bulky size, slow parsing during import, and ease of corruption.

Data Mining

This section covers data mining methods for handling challenges such as expected accuracy levels based on intended purposes, attachment, and permanence of accuracy level information to the data, integration with software tools, metadata, and more. Ma et al. (2018) and Che, Jung, and Olsen (2019) provide a detailed review of feature extraction algorithms for transportation applications which serve as the building blocks for data mining with Lidar data.

Artificial Intelligence has shown promise to enable the extraction of information from point cloud datasets. García-Gutiérrez et al. (2010) applied advanced ML algorithms to create land use and land cover maps. Their study demonstrated that techniques such as decision tree learning could greatly outperform traditional methods, providing more accurate and efficient results in classifying complex geographical datasets. Lastly, Ghosh and Lohani (2013) explored the effectiveness of clustering algorithms for Lidar data, specifically highlighting the success of density-based spatial clustering applications with noise. Their research underscored the utility of these algorithms in detecting complex data patterns, which could be instrumental in a wide range of applications, from environmental monitoring to urban planning.

The application of data mining techniques to Lidar data has significantly enhanced the analysis and prediction capabilities in various environmental and geographical studies. Lay et al. (2019) explored the use of multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS) and support vector regression (SVR) for predicting debris-flow susceptibility in Malaysia. Their study utilized a comprehensive set of conditioning factors derived from Lidar data, demonstrating that MARS outperformed SVR in predicting areas at risk, with notable success in model accuracy and prediction rates. This approach underlined the potential of data mining in enhancing natural disaster management strategies by effectively utilizing Lidar-derived DEM.

Simultaneously, Dou et al. (2019) addressed the complex interrelations of earthquake and rainfall-induced landslides through an advanced data mining approach. Their research utilized multiple data mining models to assess landslide susceptibility in Japan, enhancing the understanding of dual disaster impacts. The integration of artificial neural networks and support vector machines with Lidar data not only improved the accuracy of landslide mapping but also provided a more robust framework for regional disaster management planning. In a different

context, Rozario and Gomes (2021) applied data mining to land use classification, comparing several algorithms’ performance with and without the integration of Lidar data. Their findings indicated a significant improvement in the accuracy of land cover classification when Lidar data was utilized, highlighting the value of combining traditional methods with Lidar to overcome the limitations posed by similar spectral signatures of different land covers. Shirowzhan et al. (2020) further investigated the use of spatial statistics to analyze urban patterns, particularly focusing on the distribution of building heights. By applying Local Moran’s I and Kernel Density Estimation to Lidar data, they effectively identified clusters of higher buildings, offering valuable insights for urban planning and development. These studies demonstrate the expansive utility of data mining in extracting meaningful insights from Lidar data across different fields.

While many advances in AI show promise to improve feature extraction and data mining efforts with point cloud data, much of the extraction work requires substantial manual processing. In many cases, these are aided by semi-automated algorithms that help users extract objects based on the user providing seed points to help identify the object. Yen et al. (2021) summarize Lidar feature extraction software products, documenting information from a literature review and questionnaire distributed to state DOTs. They found that multiple software packages are often required to perform the feature extraction given that each software has strengths and weaknesses concerning the objects it can extract.

Currently, the nomenclature, definition, and attribution of extracted assets vary substantially between, and in some cases within, a state DOT. A recent initiative, Open Language for Extracted Features (OpenLSEF), focused on developing a common terminology and definition for extracting and identifying objects in point cloud data to support the architectural, engineering, and construction communities. The Model Inventory of Roadway Elements (MIRE) database is also an important step toward improved consistency to support safety studies. Many of the roadway elements defined in this database can be extracted from Lidar data.

The evolution of data mining techniques through AI technology advances, coupled with the precision of Lidar measurements, has revolutionized DOT asset management practices. Utah DOT, for example, has found high value from the mobile Lidar data integrated into their U-PLAN asset management framework.

Lidar Data Sources

This section thoroughly explores the diverse sources of Lidar data, emphasizing those that offer high-quality datasets necessary for conducting sophisticated geospatial analyses. The selection of Lidar data sources is important, requiring an assessment of the dataset’s resolution, accuracy, and coverage to ensure it meets specific project and reporting standards. As the development of Lidar technology progresses, these sources will likely enhance their offerings, increasing the scope and applicability of Lidar data across various industries.

Governmental Data Repositories

Governmental agencies such as the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) play a fundamental role in the collection and distribution of Lidar data, significantly contributing to various national and regional projects. Through initiatives such as the 3D Elevation Program (3DEP), the USGS provides comprehensive Lidar datasets that cover the entire United States. A recent study showed an ROI of 5:1 (National Geospatial Advisory Committee 3D Elevation Program Subcommittee 2023). This ROI is estimated to increase with additional investments to fund the 3DEP program to completion. This program is specifically designed to create a complete, high-quality elevation data collection that is publicly accessible, aiming to support a wide array of applications including

infrastructure development, environmental management, and risk mitigation from natural disasters. Assessments have found a substantial (5:1) ROI from this program with $690 million in benefits per annum nationally (USGS n.d.). This is expected to increase to $1 billion in benefits per annum if the 3DEP program is funded to completion within 8 years.

The 3DEP initiative offers an excellent example of how data can be rapidly accessed through web viewers to obtain information efficiently without requiring cumbersome data downloads. For instance, the detailed elevation and terrain mapping provided by 3DEP is useful for major infrastructure projects, enabling precise planning and execution that align with topographical realities. This information helps ensure that constructions such as roads, bridges, and levees are efficiently designed with an accurate and detailed understanding of the underlying terrain. By providing detailed models of landforms, bodies of water, and vegetation, these datasets can allow for thorough environmental impact studies and conservation planning, helping to preserve natural habitats and manage resources effectively. Overall, the USGS’s 3DEP program exemplifies the significant impact that government-led Lidar data collection initiatives can have on a national scale, providing data that supports a wide range of activities, from urban planning to disaster readiness and response.

Commercial Vendors

Commercial vendors play a pivotal role in the Lidar data ecosystem, supporting the collection, management, and analysis of Lidar datasets and software development. Several vendors routinely capture data across the roadway network on a frequent basis. These companies employ advanced technology to gather and refine Lidar data, ensuring that it is of high quality and ready for integration with existing GIS. The preparation and processing of this data are carefully managed to support the seamless incorporation into various industry workflows, enhancing utility in projects requiring detailed geospatial analysis. The datasets provided by these vendors support a range of applications, from urban planning and infrastructure development to environmental management and transportation safety. By offering Lidar data that meets specific criteria, commercial vendors help organizations adhere to rigorous compliance and reporting standards. This is especially useful in sectors where the precision and reliability of spatial data directly influence operational success and safety. Furthermore, commercial vendors continuously innovate to offer data products that not only meet current market demands but also anticipate future needs. This proactive approach helps ensure that industries have access to the most up-to-date and relevant data, facilitating more informed decision-making and strategic planning. As a result, commercial Lidar data vendors are integral to the ongoing development and enhancement of various industrial and governmental projects, providing a valuable resource for comprehensive and accurate spatial analysis.

Notably, in recent years there has been a substantial increase in interest in Lidar collections to generate HD maps for autonomous vehicles as well as to use the information from autonomous systems to produce asset inventory information. A key challenge resides in the differing formats and standards for storing Lidar data across these different industries. Nevertheless, the ability to harvest real-time Lidar information provides many opportunities for new applications such as asset monitoring and traffic management.

Academic and Research Institutions

Academic and research institutions are fundamental contributors to the Lidar data landscape, often focusing on the development and dissemination of highly specialized Lidar datasets. These entities engage in cutting-edge research and often collaborate on projects that push the boundaries of Lidar technology and its applications. By fostering an environment of innovation and

exploration, these institutions provide unique datasets that are sometimes made available to the public or specific industries. This contribution helps advance the knowledge base of Lidar applications and enhances the technology’s integration into real-world projects. Academic-led Lidar projects often explore new methodologies for data collection and processing, offering insights that can lead to more efficient and accurate data usage across various sectors. Moreover, research institutions frequently partner with government and industry stakeholders to ensure that the Lidar data they produce is both relevant and applicable to current and future needs. These collaborations help bridge the gap between theoretical research and practical implementation, ensuring that the benefits of Lidar technology are fully realized.

Open Data Initiatives

Open data initiatives launched by several organizations, academic institutions, and government entities significantly contribute to the accessibility of Lidar and other geospatial data. These initiatives are designed to democratize the availability of high-quality data, allowing for broader access and usage across multiple sectors, including research, planning, and development. By making Lidar data freely accessible, these initiatives encourage innovation, collaboration, and transparency in projects that require detailed spatial analysis.

An exemplary instance of such an initiative is the National-Science-Foundation-supported OpenTopography run by the San Diego Supercomputer Center at the University of California, San Diego, the EarthScope Consortium, and Arizona State University. This platform provides access to high-resolution, community-contributed Lidar data that is significant for conducting detailed environmental and infrastructural analyses. These data support a wide range of applications from academic research to practical implementations in urban planning and disaster management. By enabling easy access to quality Lidar data with detailed metadata, OpenTopography helps ensure that projects can meet rigorous national standards for transportation safety and infrastructure management, enhancing the effectiveness and reliability of these initiatives (OpenTopography 2024).

DOT Policies and Specifications

The integration of Lidar technology into DOT operations has been influenced by various policies and specifications set by different state DOTs. These policies provide guidelines on data collection, processing, and usage, ensuring standardization and QC across projects. For instance, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) has developed comprehensive guidelines for the use of Lidar in transportation projects, emphasizing accuracy and consistency in data collection and processing. Similarly, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) has outlined specifications for Lidar data acquisition, focusing on maintaining high-quality data standards for various applications including asset management and road safety analysis.

Additional Learning Resources

Several key resources provide comprehensive information on Lidar technology and its applications. These resources are invaluable for professionals seeking to enhance their understanding of Lidar, keep abreast of technological advancements, or find practical guidance on implementation. Table 5 summarizes websites, professional associations, academic journals, and educational resources related to Lidar technology.

These resources provide a wealth of knowledge and support for those engaged in the field of Lidar and remote sensing, offering opportunities for professional growth, networking, and staying updated with the latest industry trends and research.

Table 5. Information resources, organizations, and journal publications associated with Lidar technology.

| Category | Resource | Description/URL |

|---|---|---|

| Websites/Data Repositories | USGS 3DEP | Nationwide Lidar data for various applications. https://www.usgs.gov/3d-elevation-program |

| OpenTopography | High-resolution, community-contributed Lidar data https://opentopography.org/ | |

| Lidar News | https://Lidarnews.com/ | |

| Lidar Magazine | Articles, news, and case studies on Lidar https://lidarmag.com/ | |

| Learn Mobile Lidar | NCHRP Report 748: Guidelines for the Use of Mobile LIDAR in Transportation Applications (Olsen et al. 2013) | |

| Professional Associations | American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) Manual of Practice 152 | This reference manual contains a wealth of information on terrestrial laser scanning, mobile mapping, information modeling, and fundamental geodetic principles. https://ascelibrary.org/doi/book/10.1061/9780784416037 |

| ASPRS | Standards and effective procedures for Lidar, including the Geospatial Positioning Standards, and LAS format. GeoWeek (https://www.Lidarmap.org/) is an annual event discussing Lidar technological advances that is co-organized by ASPRS. https://www.asprs.org/ | |

| ASTM | Developed the e57 format for imaging systems for data exchange. This format efficiently stores point cloud and imagery data in an organized structure. | |

| Transportation Research Board (TRB) ADK70 Committee | Committee that explores and provides guidance on the use of geospatial technologies in transportation | |

| Federal Agencies | Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) | The Every Day Counts Initiative provides a wealth of resources documenting uses of advanced technologies including Lidar, UAS and BIM in transportation applications. |

| Academic Journals | ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing | Research on Lidar in mapping and 3D reconstruction; International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (ISPRS) journal |

| ASCE Journal of Surveying Engineering | Use of Lidar and other surveying technology in engineering applications | |

| IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing | Variety of papers related to mobile laser scanning technology and feature extraction | |

| Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies | Covers a variety of emerging technologies in transportation, including Lidar |