Evaluation of the Every Day Counts Program (2025)

Chapter: 4 Observations and Key Findings

CHAPTER 4

Observations and Key Findings

This section presents findings from interviews and document analysis reflecting the sentiments heard from multiple stakeholders, combined with data extracted from document review and the case studies. The following topics are discussed in the rest of this chapter

- Views on the Selection of EDC Innovations

- The Value of State Transportation Innovation Councils

- Implementation Resources and Benefits

- Addressing Inherent Constraints on Innovation

- Reporting on Implementation and Communication of Results

4.1 Views on the Selection of EDC Innovations

This section presents perceptions from stakeholders on clarity and transparency of the innovation selection process. The selection of EDC Innovations plays a pivotal role in advancing transportation innovation and delivering benefits to stakeholders. Whereas stakeholders broadly approve of the Innovations selected, there are concerns regarding the transparency and clarity of the selection process. Enhancing stakeholder engagement and communication is essential for addressing these concerns and ensuring the continued success of the EDC Program.

Community Understanding of the Selection Process

The individuals interviewed thought that the EDC Program’s innovations were valuable, although they might have doubts about one or two of the dozens of Innovations promoted. Several stakeholders interviewed stated that they would prefer more explanation from the EDC Program on how Innovations for each Round are selected. They commented that while the revealing of the Innovations was dramatic, it detracted from the idea that the EDC Program listens to the surface transportation community when making those selections. Although most stakeholders are satisfied with the Innovations chosen, there is a gap in understanding of how their input contributes to the final selection. This point was raised primarily by a few EDC coordinators and some staff from state DOTs. For example, one EDC Coordinator felt that the program was good about soliciting candidate Innovations but could not see that the community’s input was considered during selection. Another state DOT staff member suggested that the EDC Program reveal the candidates for EDC Innovations that were NOT selected for each Round, so that state DOTs would have a better idea about what kind of ideas are screened out. Another state DOT representative suggested a different approach to selection, where the state DOTs review the candidate Innovations and decide which ones are selected. This person acknowledged

that managing such a process “may pose challenges with a multitude of entities and potential innovations.”

I’m not sure where they generate the topics from. Although I never find them to be irrelevant. But I personally have never seen like an input process come through for, but that probably exists and I’ve just not seen it.

– State DOT Representative

I feel like sending ideas is open. How it gets narrowed down and all that is like a black box to me, but I don’t necessarily need to be part of that, you know, so I do feel like there’s not a lot of participation during that phase of it, but I’m not sure if there really needs to be, you know?

– State DOT Representative

A few external stakeholders commented positively on the decline in the number of innovations per Round, falling from 14 in EDC Round 1 to 7 in both Rounds 6 and 7. One of these individuals thought that seven was a reasonable number of Innovations for each state to consider at the start of the Round and that selecting a greater number of Innovations would be challenging. The prevailing view was that with seven innovations, the states could devote enough time to learning about and considering each, and the number still could accommodate enough of a variety of Innovations that at least some would be attractive to every state.

Opportunities for Broader Stakeholder Engagement

Efforts to broaden stakeholder engagement and input have been recognized within the program. FHWA stakeholders recognize that the Program Office collects ideas from various sources beyond state DOTs and AASHTO, such as associations, FHWA Offices, tribal governments, and local stakeholders. FHWA interviewees noted that more could be done to incorporate perspectives from local agencies, tribal governments, and contractor associations when selecting Innovations to promote, as those parties have an interest in how states adopt EDC Innovations but face conditions and concerns specific to their organizations.

Considering States’ Constraints during Selection

Most interested parties appreciate that the EDC Program is indeed “state-led,” as the state DOTs can elect to implement an EDC Innovation but are not pressured to do so. Several of the stakeholders raised concerns about properly considering practical and other constraints that might prevent certain states from implementing an innovation. The focus of the program on more process-oriented Innovations has brought up some new challenges. Unlike design and construction projects, which can be implemented relatively quickly, process-oriented Innovations often involve changes to policies or procedures, requiring extensive coordination and negotiation among stakeholders. This complexity can lead to slower progress and heightened resistance from parties unwilling to modify existing policies.

4.2 Value of State Transportation Innovation Councils

As noted earlier, the STICs play a key role in the EDC Program. As a multistakeholder forum, the STICs convene summits where state DOTs can have open discussions with other key stakeholders in the transportation ecosystem—private contractors, university researchers, local planning agencies, and others. The STICs are charged with naming the EDC Innovations that the state DOT will implement during an EDC Round. STICs also each can receive $100,000 in funding for innovation-oriented projects (recently increased to $125,000), such as demonstrations of new technologies.

STICs as an Innovation Support Mechanism

For most states, the STIC is viewed as a useful mechanism for convening key players from the state surface transportation community and focusing their attention on innovation. Some states are using STICs to coordinate additional programs (e.g., state-level versions of the EDC Program). One state participant described their STIC this way:

Our STIC doesn’t meet all that frequently, but it exists because of this process. . . . There are good conversations about things and how they work on the state level, the local level, all that kind of stuff. And it sort of ties our research efforts into implementation and how we [are] getting things out on the ground when we come up with new ideas. And all of that stems out of the Every Day Counts process.

The STIC was highlighted as instrumental in facilitating major innovations. For instance, Innovations such as GRS bridges and traffic queue warning systems received support through these grants, leading to their integration into standard practices. The flexibility and seed funding provided by such programs were used as examples for enabling pilot projects and enabling experimentation. Many states use the STIC grants to seed the deployment of EDC Innovations and for other innovations running in parallel to EDC Innovations.

For a lot of the State DOTs, a STIC grant is not life-changing money for an innovation, but it’s really good seed money. It’s a beginning. And we’ve used the STIC grant just about every year since 2014 to get some innovations off the ground, some of which were tied to EDC, some of which were running parallel to, and some that were not related at all.

– State DOT Representative

On the other hand, other state DOT stakeholders noted that the $100,000 is a limited amount that has not increased over the life of the program. (The STIC funding was increased to $125,000 after this evaluation project, in part to respond to these concerns.) Given cost increases, $100,000 was seldom sufficient to sponsor even a single project at a university. Deploying STIC funds also triggers accounting and reporting requirements, and some state DOTs stated that at $100,000, the amount awarded generated more hassle than benefit.

STIC funding is tough. [ . . . ] It’s not a lot of money and there’s a lot of ropes to get through to utilize the funding and having the match funding and having to report on it every six months and working through the whole process of the application. And, and it’s a lot of work just for not a ton of value.

– State DOT Representative

Additional Incentives

In addition to STIC funding, the EDC Program offers limited direct assistance to support champions of innovation. Participants found these EDC Innovation-specific funds can fund small but crucial activities. A state DOT participant involved in working with first responders on Traffic Incident Management (TIM) noted that flexible funding can offer great value:

We have to compete nationally, but we, we’ve used a lot for things like . . . to pay for travel funds. And it’s not a lot of money. I mean, it might be a trip where you can send five people and it’s about $7,000 or something. We had [a peer exchange] with [participation from] the state patrol . . . [I]f they didn’t have that $7,000, they would not have been able to do that peer exchange, at least in person. So that was huge to them.

4.3 Implementation Resources and Benefits

The EDC Program is viewed as being especially helpful by supporting IDTs, raising awareness of innovations through outreach and electronic communications, and encouraging state DOTs to consider a range of EDC Innovations. Internally, FHWA staff involved in the EDC Program

gave high marks to the EDC Program Office, and in particular to the CAI Director and the longstanding EDC Program Coordinator, for providing helpful advice, being responsive to requests, and championing the program. External stakeholders also shared positive experiences working with the EDC Program staff and highlighted the assistance that they have received from the FHWA Resource Center during implementation.

Given that the EDC Program is designed to boost the deployment of “proven yet underutilized” innovations, implementation is the focus of EDC Program activities, the major benefits and challenges of the EDC Program are apparent here.

Access to Information

An initial priority for a state considering the implementation of an EDC Innovation is gathering sufficient evidence and information to understand the risks and benefits involved. External stakeholders were broadly satisfied with how the EDC Program supports the dissemination of information. The monthly webinars were mentioned by FHWA as a great resource to share valuable information for state champions to participate and get involved. Interviewees also appreciated EDC newsletters, demonstration projects, and site visits as other useful resources to gain confidence in the choice to implement an Initiative.

As noted elsewhere, a barrier to the adoption of some proven EDC Innovations is a lack of awareness among state DOTs that the innovation exists. The Data-Driven Safety Analysis (DDSA) Innovation in EDC Rounds 3 and 4 promoted the use of computer modeling and data analytics as one approach to integrate safety considerations in roadway design. This approach had been published by AASHTO in 2010 as the Highway Safety Manual (HSM), but FHWA found that few states were aware of the HSM or how it could be useful. Rather than creating an Innovation specific to the HSM, the EDC Program designed the DDSA Initiative with a broader scope looking at all uses of digital data to enhancing roadway safety. Given the novelty and complexity of some elements of DDSA, state DOTs stated that peer exchanges were especially useful in advancing implementation. In particular, one exchange held during EDC Round 4 involved participants from 43 states. Case studies of states that successfully implemented DDSA, developed by the EDC Program or sometimes prepared by the states themselves, also provided helpful support.

One party mentioned a particular benefit to the information shared by the EDC Program. While leading the implementation of an EDC Innovation, this person found that his managers were more easily persuaded to support the EDC Innovation because he used data from the EDC Program at the FHWA website. State DOTs are more likely to trust data and guidance from the FHWA than similar information from consultants.

However, some shared that sometimes there was too much information coming their way and it was hard to know what was beneficial and what was not. These stakeholders noted that their schedules and workload did not provide enough time to review all the materials provided, so they could use some guidance on where they should focus their limited attention. Additionally,

some state DOTs perceived that, although information was very helpful and there was good data to support the EDC Innovations they were promoting, more support for marketing was needed.

Access to Experts and Customized Guidance

One feature of the EDC Program raised repeatedly by stakeholders as a clear benefit is the Program’s work to provide state DOTs with access and knowledge from other state DOTs. Both state DOT participants and representatives of IDTs (mostly FHWA staff) noted repeatedly that the state DOTs are most eager to learn from each other.

Before rolling out e-Ticketing and Digital As-Builts technologies, the EDC Program held the annual summit, conducted case studies, and provided relevant data as part of the implementation plan. Among these activities, peer exchanges emerged as the most impactful, allowing lead states to showcase their adoption of the innovation, thus encouraging other states to follow suit. Currently, efforts are underway to compile a “Getting Started Guide” along with complementary how-to documents and case studies to facilitate the adoption process.

In that vein, the peer exchanges organized and supported by the program were highlighted by multiple stakeholders as extremely valuable. As one stakeholder put it, there is no substitute for learning about implementation from “someone who’s been there.”

The peer exchange aspect is probably the most outstanding one because it can take so many formats. Again, it can be in person, it can be virtual, it can be a smaller group, it can be a larger group. It can be a scan tour where you go and see how another state has piloted innovation and decide if that will work for you or if you need to do some tweaks.

– EDC Coordinator

After the peer exchanges, the monthly webinars were also mentioned frequently as a mechanism to hear presentations from representatives of “early adopter” states. One EDC Implementation Team Member summarized their experience like this:

Webinars are pretty well-attended; the case studies and facts sheets are popular. We utilize face to face interactions with peer exchanges and demos, tech demos are very popular, we find that face to face interaction is the most beneficial.

The national EDC Summit is also a key activity for learning about the new Round’s EDC Innovations, often from state DOTs involved with the IDTs. However, several stakeholders noted that the value of the summit has decreased since moving to a virtual format due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Most regional meetings and summits for state-level EDC discussions have also become virtual. Stakeholder feedback suggests that the virtual format lacks the personal touch and interactive opportunities that in-person events provide.

There is also frustration with repeated virtual events (e.g., webinars and online peer exchanges), particularly when topics overlap, leading to a sense of monotony and reduced engagement. One state DOT representative noted, “I don’t like repeated virtual requests for peer exchanges and summits when the topic has a lot of overlap. Like, there’s only so many times I want to be in a virtual room with the same people talking about kind of the same topic.”

One significant outcome of these exchanges was the formation of communities of practice within various sectors and specific innovations. These networks facilitate ongoing communication, webinars, and discussions about specific innovations, fostering enduring relationships among participants. This cultural aspect of relationship-building is deemed crucial, as it encourages collaboration among stakeholders who share common goals and challenges. Stakeholders recommended identifying ways to maximize benefits of virtual and in-person engagement for community building and knowledge sharing. One state DOT representative noted, “And together, that information sharing, that peer exchanging that would happen was really, really, really powerful for us. You know, not to take anything away from the topics, but I think that’s what’s really important about is that culture. It kind of forced us all to the table to talk about some of those things.”

4.4 Addressing EDC Innovation Risks, Challenges, and Culture

The OECD and others have documented the challenges that public-sector organizations face in developing an innovation-oriented culture. As noted in Chapter 1, risk is inherent in implementing innovations, as the adopting organization lacks familiarity with the innovation. The EDC Program addresses the potential risks and challenges of the EDC Innovations through the implementation plans, which outline strategies to help state DOTs understand the risks and challenges of implementation. The plans also describe resources and activities to help state DOTs mitigate these risks and overcome challenges.

The EDC Program seeks to facilitate the deployment of EDC Innovations through its activities and resources. By doing so repeatedly, the program can enable each state DOT to find a “playbook” for implementing innovations, giving them the capacity to properly estimate the risks involved in future implementations and then develop their own plans. Some of the strategies employed by the EDC Program are described here.

Assisting with Financing and Funding

For implementations that involve substantial upfront or ongoing costs, the EDC Program can connect state DOTs to the FHWA Resource Center (see box). Those staff, with the state’s FHWA Division office, can identify sources of funds to support implementation. Dedicated programs to accelerate deployment can be accessed for the implementation of EDC Innovations.

EDC Innovations focused on digital systems and processes, including e-Construction, e-Ticketing, and 3D Engineered Models, often involved financial investments prior to implementation. In the e-Construction Innovation, the IDT found that the high start-up costs (for IT hardware and software systems) and substantial re-training posed challenges that slowed adoption in state DOTs. The FHWA encouraged the use of STIC and AID funds to states seeking to implement e-Construction and e-Ticketing.

Managing Organizational Dynamics and Barriers

EDC Innovations often entail two key organizational risks. Internal risk comes from potential resistance to innovation from within the state DOT. The resistance can stem from uncertainty

about innovation, comfort with established routines and processes, and fears that an innovation will disrupt existing DOT offices and their designated responsibilities. For example, EDC Innovations to digitize different processes within DOTs may require information sharing between safety departments, maintenance and operation, and planning. This is the case with the Data-Driven Safety Analysis Innovation (see box). External risk stems from the need to coordinate across different stakeholder organizations to implement the innovation. For example, the Data Analytics case notes that Innovations such as TIM require cooperation among state DOTs, first responders, and local governments.

Each EDC Implementation Plan typically identifies the key internal and external stakeholders who need to be involved in a successful deployment of that Initiative. The plan gives the state DOTs early warning about the problems that could occur if a key stakeholder is overlooked. For external organizational issues, the plan will likewise identify other organizational stakeholders to be consulted. The EDC activities, such as peer exchanges and webinars, are open to those other stakeholders. The state DOT can also leverage any data or other resources provided on the EDC website. The communities of practice mentioned above are a common mechanism for coordinating deployments across organizational boundaries, as well as sharing knowledge to facilitate implementation.

Data-Driven Safety Analysis Innovation

Some Innovations promoted by the EDC Program required collaboration and coordination across traditional organizational boundaries. For the DDSA Initiative, state DOTs found that the safety section held most safety data, but the analytical models required additional data (roadway feature data, traffic volume) held by other departments and even other agencies. The EDC Program extended DDSA into Round 4 to facilitate involvement by new partners in implementation, especially local agencies, tribal governments, and rural authorities. For example, the Kentucky DOT examined three rural counties and brought first responders (police and fire) into the discussion. Those emergency responders were very familiar with sections of roads and the types of features present where severe crashes had occurred, which provided a way to prioritize DDSA implementation. Their participation was supported in part by EDC Program resources.

Managing Political Risk: the Role of Champions

Deployments of EDC Innovations in a state DOT can be derailed by environmental factors, such as a change in leadership that moves the organization in a different direction, or a budget cut that suddenly eliminates resources to support deployment. To ensure successful implementation, several implementation plans noted the importance of “champions”—individual staff members who are excited about the EDC Innovation and push to enable deployment. The Final Report for EDC Round 3 includes a quote from Jennifer Cohan, then the Secretary of Transportation for the state of Delaware (FHWA 2017):

An innovative culture is difficult to quantify, but it starts with innovation champions and making sure the message reaches every person in the department that they are empowered to innovate. It’s a top-down, bottom-up mentality.

Champions generally self-identify at the start of an implementation effort. They often can maintain the momentum behind a deployment when organizational barriers arise. One key

function of a champion is to recruit staff who may be indifferent to the EDC Innovation but can be convinced to contribute to the effort. An EDC Coordinator noted, “And those are some of the ones we have to kind of work on a little bit more because they’re kind of a little voluntold to do this and they have to try to fit it into their current job. And it wasn’t something that they started out with a passion for.”

Risk from Insufficient Human Capital

A common message from stakeholders was that most state DOTs suffer from personnel shortages. State DOT representatives were concerned about how the loss of experienced personnel through attrition detracts from their agencies’ expertise and institutional knowledge. The dearth of trained staff was cited by many stakeholders as a key barrier to EDC Innovation adoption. An EDC State Coordinator commented, “[The States] just can’t afford to hire people. They can’t afford to keep people. And on top of that, the people that they do have are busy doing all kinds of other things.”

The EDC Program has been addressing this somewhat through specialized training associated with its Innovations and person-to-person knowledge exchange. Unfortunately, sometimes the key to successful deployment is the insight generated by experience, so new staff have not had the opportunity to build that foundational knowledge-base. For example, during a pilot project for Intelligent Compaction (IC) state workers did not have the time to enter density testing values into a spreadsheet so they could be compared with compaction measurements. For this reason, potential IC advantages were unable to be verified and reported, resulting in a failure to complete the implementation. While that missing step seemed simple, the shortage of personnel was the cause of the problem. A state DOT staff member involved in that effort noted, “They’re [state DOT workers] not here to defend themselves. I’m giving them credit. They were buried. They had a lot to do with a big job. They’re under-staffed. I guarantee all those things were the case.”

This lack of state staff time may limit states participation in future EDC Innovations. One state DOT representative indicated that innovation activities need to be integrated into formal responsibilities with dedicated work time. “I don’t think there’s a lack of desire to be innovative . . . I mean, these people all have their day jobs . . . they have to be able to weave in what they’re trying to be innovative at within that.” A state DOT manager noted, “Staffing is an issue for adoption, decisions depend on the culture and leadership of DOTs, but there is only so much state DOTs can do. A lot of states are restricted to a couple Initiatives and can’t do them all.”

The integration of new information systems and technologies in highway construction has required state DOTs to leverage and advance their workforce’s existing digital skills and competencies. The EDC Innovations related to digitization addressed this barrier directly. In the 3D Engineered Models Innovation, the EDC Program worked first on developing awareness among owners, contractors, engineers, and industry on 3D modeling and its benefits. Then, the EDC Program aimed to boost human capital by increasing the number of professionals within each target area in the workflow, processes, and procedures of 3D modeling. In addition, the EDC Program deployed on-the-ground technical assistance to help states use the technologies using hands-on demonstrations.

4.5 Reporting on Implementation

The EDC Program includes a provision for states to report on the initial level of implementation for each EDC Innovation at the start of each Round and update their progress every 6 months through the Round. A recent reduction in reporting frequency was seen as overwhelmingly positive and stakeholders appreciated the diligence from FHWA on communicating deadlines and sharing templates.

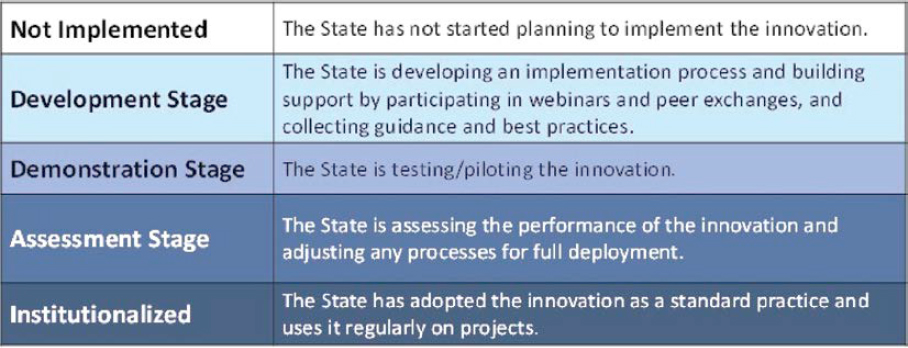

Interview comments indicate that some stakeholders have difficulty with the definitions for certain implementation stages when applied to specific EDC Innovations. The EDC Progress Reports require that the state select which of the five levels of implementation the state has achieved (see Figure 4). The IDTs generally try to define the criteria for a state to qualify for advancing to a higher level of implementation, but even the IDT team leaders found some EDC Innovations were not structured to help. Two respondents noted that the progress reports for each state are filed by the EDC Coordinator for that state, who is often not a technical expert in every innovation and may not properly judge the state’s implementation level.

The IDT team members and state DOTs noted that the current reporting structure lacks the granularity needed to be actionable. For example, the Pavement Preservation Innovation promoted the implementation of 8 to 10 different paving materials and techniques. A state that uses some of those techniques in a few geographic areas could be considered at the demonstration stage (limited testing), but if the instances of implementation represent full deployments, it might be considered at the institutionalized stage. The Pavement Preservation IDT developed its own set of stages with accompanying criteria, allowing states to report themselves as follows:

- National Leader: The Transportation Agency has successfully deployed revised preservation treatment specifications, provided training for construction and inspection personnel, incorporated improved material qualities into treatment specifications, or adopted improved construction practices on at least three projects or 10 miles of preservation treatment.

- Under Assessment: The Transportation Agency has chosen and constructed one or two new successful pavement preservation projects applying the improved construction practices.

- Exploring: The Transportation Agency has requested information and/or training about revised specifications, inspection methods, construction technologies, or quality materials.

- Discussing: The Transportation Agency is seeking information and designing a new pavement preservation treatment.

The e-Construction Innovation was not a single technology, but instead encompassed multiple systems and processes that represented different components of Construction Information Management (CIM). That approach helped state DOTs implement the EDC Innovations, because they could choose among different technologies in each EDC Innovation to implement first. However, this complicated reporting on implementation progress, as the deployment of only some technologies in only some instances could constitute “institutionalization” in a local context. Determining the point at which a state had implemented a sufficient set of technologies to move to a more advanced level of implementation could generate confusion, and some IDTs had to develop and encourage creative methods to help states properly classify their levels of implementation.

Reporting requirements have been a source of tension for EDC Program participants. A few stakeholders recognized that the EDC Program is faced with a quandary. Its progress reporting system needs to use a single standardized scale for representing implementation progress. However, EDC Innovations vary greatly in nature, and the level of deployment is often unevenly distributed across a state. The state DOTs and EDC coordinators are caught in a situation where they try to reconcile these needs, leading to administrative headaches. As one FHWA staff person summarized, “The challenge is to give EDC a way of measuring success, the reporting piece is a sore subject for starts. We participated in at least 6 calls with states for EDC 7 assuring them not to worry too much about reporting, that contractors can help with reporting. We have been successful in convincing states we won’t harass them and that we will help states work through this process—The ‘EDC police’ won’t come after you.”