Implementing Data Governance at Transportation Agencies: Volume 1: Implementation Guide (2024)

Chapter: 3 Getting Started

3. Getting Started

Overview

This section provides step-by-step guidance for getting started with data governance – how to assess the current situation, establish goals, and create a roadmap tailored to the agency’s needs. There are nine steps, illustrated in Figure 1.

Tips for Planning a Data Governance Initiative

- Keep your ultimate business goals in mind – focus on adding value and avoid creating unnecessary processes

- Identify and build on what is currently working well

- Don’t try to do everything at once – set up a structure, provide value and then expand

- Push responsibilities down to the lowest possible levels but provide an escalation path for issue resolution

- Keep in mind that data governance requires changes in behaviors – communication and change management are essential for success

Adapt the process to your situation. This nine-step process can be adapted to situations where data governance is being implemented in a limited fashion. Regardless of the scope, It is still important to identify stakeholders, establish goals, assess current practices to identify gaps, determine a governance approach and make a plan.

Consider creating a data plan. Some agencies choose to launch a data governance effort by creating a data business plan or data strategic plan. The plan development process can be structured to carry out steps 2-8 of the data governance initiation process shown in Figure 1, producing a plan with a roadmap and initial action plan.

This will be an iterative process. You will learn as you undertake these activities, which will lead to course corrections. In addition, there will also inevitably be changes in agency leadership and changes in staff with direct involvement in the data governance effort. These changes will also necessitate re-examination of assumptions and decisions and create the need to modify your plan. That is the reason for Step 9-Implement, Monitor and Adjust.

Step 1: Identify a Lead

Every new initiative needs a leader. Data governance, like any major initiative, requires a lead to steer the effort. Therefore, the first step in launching data governance will be to identify a suitable person to play the lead role. The person responsible for launching a data governance effort is not necessarily the same one who will be designated to manage it once it has been established.

Potential Data Governance Leads

- GIS Manager

- Planning Director

- Performance Management Lead

- Asset Management Lead

- Business Analyst

- Transportation Data Program Manager

- Data Analytics Lead

- IT Manager

- Chief Information Officer

Find the right person. There is no single best organizational home or role for the lead, but there are some qualities that will contribute to their success:

- Management support—close working relationship with a Deputy or Division-level manager who serves as the executive champion for the effort;

- Interpersonal and communication skills—ability to get along with a variety of individuals across the agency: an effective collaborator, communicator, and change agent;

- Data experience—two to five years of experience working with data – as a user, data manager, or database or report developer;

- Project management experience—understanding of how to plan, track, and control a project;

- Logical and analytical mind—ability to formulate logical arguments and approach problems in a systematic fashion; and

- Passion—strong interest and commitment to improving the agency’s use of data.

Failure to assign responsibility to make sure data governance happens is one of the most commonly cited reasons when agencies say they have tried and failed to establish or maintain a data governance effort. Another related reason for failure is putting the wrong person in charge. A person who does not feel supported, empowered, or who does not want to do the job will not succeed.

Sample Stakeholder Group Composition

- Executive Champion (Deputy or Division manager)

- Managers representing data-intensive business units (e.g. financial management, project data management, asset management, system operations)

- Data Program Managers (e.g., GIS lead, traffic monitoring lead, road inventory lead, survey/remote sensing lead)

- IT managers responsible for data management, data warehouse, and data architecture functions

- Field office representatives (if applicable)

- External partner agency representatives (if applicable)

Step 2: Identify and Assemble Stakeholders

Organize a stakeholder group. Once the lead has been determined, the next step is to identify and assemble an initial group of stakeholders to serve as a steering committee for data governance planning. This group will be responsible for early outreach and assessment activities, formulating goals, selecting a data governance structure and approach, and establishing a roadmap and action plan. Many agencies hire consultants to help them with these early steps; in this case, a strong stakeholder group can review deliverables and connect the consultant team to different parts of the organization.

Select the right collection of members. The data governance effort will eventually benefit from the broad participation of stakeholders who collect, manage, and use data. However, starting a data governance effort with the large superset of all who have a stake in the data can overwhelm the early efforts. The initial stakeholder group should consist of 5-10 people who have the knowledge, positional authority, organizational savvy, and interest to set the right strategic direction for data governance and help to move it forward to implementation. Therefore, placement in the organization as well as personal qualities are important factors to consider in identifying members of this group.

External Stakeholders to Consider

- State-level data governance leads

- State-level IT (especially for states with centralized IT functions)

- State-level geospatial data management units

- E911 agencies

- Federal partners (e.g., FHWA Division office staff with a role in funding or overseeing data improvement initiatives)

- Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) or Regional Planning Agencies (RPAs) with well-developed data programs and interest in data sharing

- Major transit providers

- Traffic Records Coordinating Committees (TRCCs)

- Other interagency or multijurisdictional groups with data-related missions

Include both supporters and skeptics. Each member of the stakeholder group should be motivated to participate because they see the potential for data governance to benefit their area of responsibility as well as the organization. However, it can be helpful to include a few skeptics in the group who will ask hard questions about costs and value to be added. Their motivation for participating may be to prevent the organization from adopting new policies and procedures that impede flexibility, which is an important consideration to keep in mind.

Consider including content and records management representatives. There may be opportunities for synergies and resource pooling across data, content and records management. For example, consistent metadata for data and content enables users to search across different types of information. A coordinated approach to retention and archiving for datasets and documents avoids establishing separate and potentially duplicative or inconsistent processes. Involving individuals responsible for content and records management functions allows for early discussion of collaboration opportunities and consideration of whether to adopt a broad information governance scope or keep the data governance scope limited to structured data.

Consider engaging field office representatives. If the agency has strong and semi-autonomous field offices (e.g., Districts or Regions), it is a good idea to include field representation in the stakeholder group. This will help the group discuss the impact and benefits of data governance from the field office perspective. Ideally, the field representatives will buy in to the decisions about data governance that the group reaches and can serve as effective communicators and ambassadors to other field offices once data governance is being rolled out.

Consider engaging external stakeholders. In some situations, it may be beneficial to include representatives of partner agencies, either as full working members of the initial data governance stakeholder group or in an advisory capacity. They are very often partners at the Tribal, local or regional level in asset management, planning, design, and safety projects. They may supply

corrections and updates to the DOT’s spatial data, traffic data, and other key data sources to which the DOT would like to have improved access. Furthermore, these agencies benefit from the data provided through state-level initiatives, and the mutual exchange of data can be the foundation for formal partnerships. In addition, the e911 agencies throughout a state have data sources that can be shared with local agencies and the DOT to help validate local spatial information.

Determining when and how to engage external stakeholders. The choice to engage external stakeholders as full group members depends on the agency’s motivations for pursuing data governance. For example, if compliance with state-level data governance guidelines is a key motivator, then including a state-level representative is warranted. Another consideration is the willingness or ability of the external stakeholders to make the necessary time commitment. Some agencies may want to wait until goals are clarified (Step 4) to determine which external stakeholders to engage, when, and how.

Standing Up Data Governance: Connecticut DOT

The Connecticut DOT working-level stakeholders had started a grass-roots effort to improve data when the agency signed up for a technical assistance program offered by FHWA aimed at developing data business plans. The ultimate goal of the technical assistance was to encourage states to establish data governance if they didn’t already have a program in place, or to strengthen existing data governance programs. The Connecticut DOT staff used the technical assistance to develop a presentation for senior management explaining the benefits of data governance. The hope was that they could win executive level support to start down the road of eventually creating a data governance board. Approximately five minutes into the meeting, the senior member of executive team said she had been anxious for the agency to begin data governance and that the group should go forward with their plan to establish the data governance board immediately. The DOT has had data governance ever since.

AASHTO Core Data Principles

Data should be:

VALUABLE-Data is an Asset

AVAILABLE-Data is open, accessible, transparent and shared

RELIABLE-Data quality and extent is fit for a variety of applications

AUTHORIZED – Data is secure and compliant with regulations

CLEAR-There is common vocabulary and data definition

EFFICIENT-Data is not duplicated

ACCOUNTABLE-Decisions maximize the benefit of data

Step 3: Establish a Common Understanding of Data Governance

Educate the stakeholder group. The first set of stakeholder group meetings should be devoted to educating members to provide a common understanding of what data governance is and how it might benefit the agency. There will be varying levels of understanding of data governance, and varying interpretations and assumptions about what it is.

A good place to begin is by reviewing the AASHTO Core Data Principles. These provide a foundational understanding of what transportation agencies are

trying to achieve. Many DOTs have adopted these principles, sometimes with minor modifications.

Additional topics to cover include:

- Definition of data governance

- Components of data governance

- Applicable state laws, rules and regulations related to data governance

- Common pitfalls and success factors

- Factors or pain points that are motivating the agency to implement data governance

As part of the education process, consider reaching out to other transportation agencies that have active data governance programs in place to hear first-hand about what they did and the benefits they have seen.

![]() See Chapter 8 for a curated set of references about data governance.

See Chapter 8 for a curated set of references about data governance.

Data Governance at Florida DOT Provides …

- Reliability – Ensuring information is secure, accurate, reliable and at the appropriate level to empower you to do your job better.

- Accessibility – Providing the ability to access relevant business data more quickly and efficiently by knowing where to find it.

- Timeliness – Reducing the amount of time to locate the data you need and more time to analyze the data.

- Productivity – Effectively sharing information across our organization to enable better and faster decisions.

- Integration – Enabling a greater capability to link data together from different Districts, Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise, functional areas, and systems.

- Sharing – Removing barriers currently in place that prevent the efficient sharing of information.

Aligning Data Governance with Agency Priorities (examples)

- Safety – standardizing and integrating crash, roadway and traffic data

- Operations – making effective use of available real time data sources for multiple purposes

- Performance – improving available data for meeting federal, state and agency-level performance measurement needs

Step 4: Identify Your Goals

Scope xxx

The first step in shaping a data governance effort is to establish a scope. This will help to set appropriate goals and focus the remaining activities in the nine-step process.

What Units and What Data? Options for initial scoping of data governance are:

- Option 1 - Selected data program(s). In this option, data governance is applied at the data program level – for example, road inventory data, traffic monitoring data, or data to be brought into a data warehouse, enterprise GIS database or other central data repository.

- Option 2- Selected business units. In this option, the scope of data governance is limited to one or more related business units – for example, asset management, performance management or safety management.

- Option 3 - Agency-wide, selected data. In this option, the program is agency-wide, but only certain types of data are considered in scope - for example, data stored in enterprise systems, data pertaining to the transportation system, data that are shared widely, data that are reported externally, data that are private or sensitive. You may also want to be specific about whether you will be governing just structured data or documents as well.

- Option 4 - Agency-wide, all data. In this option, the initial data governance program is comprehensive in scope, covering all business units and all types of data.

The selection of an initial scope will depend on your motivations for pursuing data governance and the level of management buy in or commitment that exists. An agency-wide scope for data governance (options 3 or 4) will be best for agencies that need to address state-level data governance requirements, and those committed to a long term, sustained effort to improve the quality and value of data for decision-making.

![]() See Chapter 2 to review motivations for implementing Data Governance – these will provide ideas for establishing goals.

See Chapter 2 to review motivations for implementing Data Governance – these will provide ideas for establishing goals.

Some agencies may choose to begin with options 1 or 2 to address priority pain points or opportunities. These options may also be pursued initially because they require less resourcing and provide an opportunity to test approaches and demonstrate value prior to an agency-wide rollout.

Business Goals for Data Governance

Once the scope has been established, the stakeholder group can initiate a discussion of what you intend to accomplish through data governance and how this aligns with the agency’s strategic directions. Key questions are:

- What problems are we trying to solve?

- What is our vision for how things will be different in the future?

- How can data governance help us to accomplish our current priorities?

- What is our data and analytics strategy – and how can data governance support it?

- What is the value proposition for data governance at our agency?

![]() See NCHRP Web-Only Document 419: Implementing Data Governance at Transportation Agencies, Volume 2: Communications Guide for guidance on creating a data governance communications plan defining target audiences, key messages and communications delivery methods.

See NCHRP Web-Only Document 419: Implementing Data Governance at Transportation Agencies, Volume 2: Communications Guide for guidance on creating a data governance communications plan defining target audiences, key messages and communications delivery methods.

The product of this step is a set of goal statements that can be used to communicate to agency leaders and others.

At this stage, focus on identifying data-related pain points that:

- pose risks;

- create inefficiencies;

- prevent the agency from meeting state or federal requirements; and/or

- hold back progress on key initiatives for improving safety, project delivery, asset state of good repair, mobility, and other key agency program areas.

In Step 5, you will be gathering more detailed information about current practices and identifying specific gaps to be addressed.

Data Governance at Caltrans

Mission:

Providing reliable, accessible, shareable, quality controlled, and documented data for use by Caltrans and its partners to support analysis and decision-making.

Goals:

Data Value. Increase the value of agency data for decision-making.

Data Sharing. Maximize sharing of existing data across agency business units.

Data Literacy. Build agency staff awareness of available data sources and capabilities to make effective use of data.

Data Efficiency. Reduce data redundancy.

Data Consistency. Increase data consistency and interoperability.

Data Protection. Protect sensitive and confidential data from unauthorized access.

Table 1 presents typical DOT problems or issues and associated goals for data governance that can be used as a starting point for discussion.

Table 1. Typical DOT Data Governance Goals

| Problem/Issue | Goals for Data Governance |

|---|---|

| There are new state-level data governance requirements, and we are not set up to meet them. | Designate roles/responsibilities and establish processes needed to comply with state-level data governance laws. |

| Different business units are collecting or purchasing duplicative data – creating inefficiencies. | Coordinate data acquisition activities across the agency. Create and manage a data inventory/catalog so that we know what data we have. |

| We would like to build authoritative data for reporting and analysis but there are multiple sources for different types of data, and it isn’t clear which one(s) to use. | Establish a process to identify authoritative data sources for reporting. |

| We are being held back from doing the kind of data analysis we’d like to do because of the lack of interoperability of our data – it is difficult to link up different data sets about projects, funding, and transportation assets. | Create data element standards and support their implementation in new information systems. |

| We are dependent on partner agency data for getting a complete picture of transportation system inventory, traffic, and safety – but it is difficult to obtain updated data from them. | Establish processes and agreements for data sharing with partner agencies. |

| Data quality is uneven, and we can’t rely on it for decision-making. | Improve data quality management practices. |

| Problem/Issue | Goals for Data Governance |

|---|---|

| There are many spreadsheets and other desktop or file-based datasets that have data important to our agency. Many are not documented or well-designed and may be lost or rendered unusable if their current owner/manager leaves the agency. | Identify “at risk” datasets and bring them into enterprise systems. |

| There are older “orphaned” datasets that need to be cleaned up or archived. | Establish clear responsibility and accountability for data. |

| It is difficult to access data outside of an employee’s immediate business unit because people are reluctant to share the data they collect/manage. | Clarify agency expectations for data sharing. |

Stakeholder Engagement

To inform the process of formulating goals, seek input from agency leaders, business line managers, data managers and data analysts. Make sure to include the largest data producers and consumers.

Plan and organize outreach activities – including surveys, interviews, webmeetings, and workshops to learn about stakeholder concerns, pain-points and perspectives on data governance. These activities are time-consuming but are important to shape an effective data governance program and obtain the buy-in necessary for successful implementation.

A strong stakeholder engagement effort will provide a solid foundation for the goals that you establish. It will make people in the agency feel heard and help to build awareness of what data governance is and how it can help.

![]() See Chapter 7 for a list of sample stakeholder interview questions.

See Chapter 7 for a list of sample stakeholder interview questions.

Step 5: Conduct an Assessment

Purpose of an Assessment

A structured data governance assessment can provide an opportunity to examine your current practices and identify the gaps between where you are and where you want to be. This provides the basis for discussing what actions your agency can take to close these gaps. Actions can be prioritized and become the basis for a data governance roadmap (Step 7) and action plan (Step 8).

The assessment can be repeated periodically and used to track progress and revise priorities based on what has been accomplished and learned.

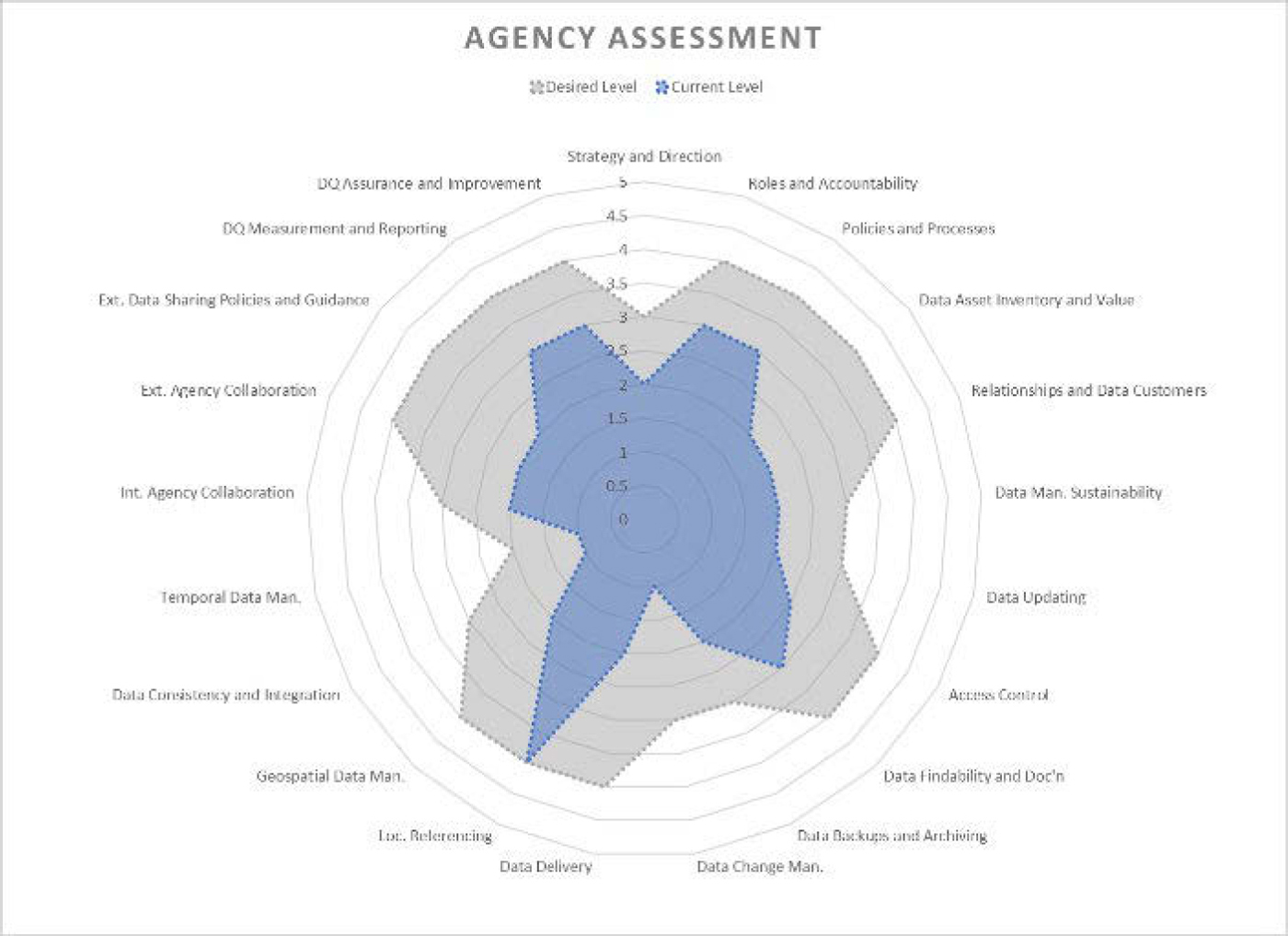

An assessment produces a score on a maturity scale (e.g., from 1 to 5) for several different aspects of data governance. The score can be valuable for communicating the need for data governance to agency leadership. However,

the process of going through the assessment is equally – if not more valuable. It provides those engaged in the assessment an opportunity to reflect on the agency’s current situation with respect to data governance and management and share their perspectives on this. It also gives participants a more in-depth understanding of what it means to advance data governance practices.

The DOT Data Assessment Tool

A data governance and management assessment tool is available as a supplemental resource to this Guide on the National Academies Press website (nap.nationalacademies.org) by searching for NCHRP Web-Only Document 419: Implementing Data Governance at Transportation Agencies, Volume 1: Implementation Guide. This tool is based on a maturity model developed specifically for transportation agencies as part of several National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Projects [2], [3]. It covers five aspects or elements of data governance and management practice:

![]() See Appendix A for the full DOT data governance and management assessment maturity model.

See Appendix A for the full DOT data governance and management assessment maturity model.

- Data Strategy and Governance – Leadership and management practices to manage data as a strategic agency asset.

- Data Life Cycle Management – Managing data throughout its life cycle from collection to archiving or deletion.

- Data Architecture and Integration – Technical standards, processes, tools, and coordination mechanisms to maximize data integration and minimize duplication.

- Data Collaboration – Internal and external collaboration to maximize data sharing and avoid duplication of effort.

- Data Quality – Standards and practices to ensure that data are of sufficient quality to meet users’ needs.

These elements are broken down into multiple sub-elements. For example, the Data Strategy and Governance element includes:

- Strategy and Direction – Leadership commitment and strategic planning to maximize value of data to meet agency goals.

- Roles and Accountability – Clear roles, accountability, and decision-making authority for data quality, value, and appropriate use.

- Policies and Processes – Adoption of principles, policies, and business processes for managing data as a strategic agency asset.

- Data Asset Inventory and Value – Tracking of agency data assets and their value.

Each sub-element is assigned a maturity rating from 1-Initial to 5-Sustained. Figure 2 below shows an example radar chart that is produced from the tool that shows the gap between current and target maturity levels for different sub-elements. The blue area in the middle represents the current state; the gray area represents the gap between the current and target states.

While the assessment tool described above was created specifically for DOTs and serves as a supplemental tool to this Guide, there are a variety of other available data governance maturity models and assessment tools. Agencies can review what is available and choose one that suits them best.

Understanding Current Practice

In conjunction with an assessment of data governance maturity, consider other activities to review and understand current practice and inform future steps:

- Review existing data and information-related policies and procedures that may need future revision or replacement.

- Conduct interviews or listening sessions with key stakeholders to understand current practices for data publication and sharing, and to identify pain points.

- Compile a list of recent data collection activities and purchases and identify how these were resourced and what coordination and communication took place.

Supplementing the Assessment

In addition to conducting a broad assessment of data governance and management maturity, agencies can consider gathering more detailed information for particular categories of data, including:

- An inventory of datasets – contents, size, where stored

- Costs of data gathering/collection, processing, and management

- Data customers – internal and external, how they use the data

- Short- and long-term data improvement needs - considering data quality, availability, and accessibility

- Anticipated changes to data needs based on new legislation, reporting requirements, or agency initiatives.

This more granular level of assessment can be time consuming. It is best conducted once data stewardship roles have been defined, so that stewards

can be engaged in the process. However, if the data governance effort is scoped at the data program or unit level, detailed information gathering is feasible and can provide a solid anchor for developing a data governance roadmap and action plan. Information on data use and costs can also be valuable for prioritizing activities and identifying opportunities for cost reductions.

Refine Your Goals

Based on the results of your assessment, take each gap that was identified and try to assign it to one of the goals established in Step 4. For example, a gap might be the lack of an agency data catalog. This gap would fit within a goal related to data sharing or ability of employees to find what data is available (findability).

Update or augment the high level goals as needed to make sure that all of the identified gaps are accounted for. Create a matrix that maps the gaps you intend to address with the final set of goals. This matrix can be used to guide the roadmap and action plan activities in Steps 7 and 8.

Step 6: Select a Governance Approach

Once there is agreement on goals for data governance and the gaps in practices to be addressed, the next step is to consider alternative approaches to data governance and decide on an initial approach. Key questions to ask are:

- What is our initial data governance operating model?

- What level of change should we pursue?

Data Governance Compliance

Some agencies have struggled with getting staff to implement new data governance policies and procedures because there are no consequences for lack of compliance. Here are some tips for approaching this challenge:

- Build awareness and support for the new policies and procedures. Make sure people understand their purpose and the WIFM (what’s in it for me). Make use of champions and sponsors to socialize new practices.

- Allow some time for a shake-out period before enforcing new policies and procedures. Seek feedback, and provide support to facilitate implementation.

- Establish approval or sign off processes for data publication or putting new information systems into production.

Operating Model

As used in this Guide, a “data governance operating model” refers to where and how data policies, standards and practices are created and implemented. An operating model for data governance is characterized by two dimensions: (1) the degree of centralization and (2) the degree of compliance focus for implementation. Three basic options can be distinguished:

Option 1 – Centralized-Command and Control. In this option, central governance bodies develop policies and standards and set up mechanisms to make sure that they are followed. There is a strong compliance focus.

Option 2 – Centralized-Facilitated. As in the first option, central governance bodies develop policies and standards, but they act as conveners and facilitators rather than enforcers. There is an emphasis on communication, consensus building and issue resolution

– showing people the right path and enabling them to do the right things.

Option 3 – Decentralized-Coordinated by an Operating Unit. In this option, there is an operating unit in the agency with responsibility for coordinating and supporting data governance activities. The focus is on enabling data creators and users to make improvements that create business value. The unit responsible for data governance develops strategy and direction, provides advice and technical support, and helps to remove barriers that block progress. Rather than standing up new data governance bodies, they seek guidance and input from existing management groups and steering committees. They set up work groups as needed to provide necessary coordination for specific initiatives.

Selecting an initial operating model should be based on the nature of the goals you have set and the size and culture of the agency. Option 1 may be most appropriate in agencies with a hierarchical culture – and when there is an emphasis on data security and response to external regulatory requirements. Option 2 is more suitable for agencies that don’t yet have the leadership buy-in to enforce changes to existing processes – and those who value consensus approaches to decision-making. Option 3 is suitable for agencies that have an operating unit with the capacity and management authority to support data governance and have goals that emphasize business enablement. Option 3 is also the most suitable for limited scope data governance efforts within a single data program or business unit.

Keep in mind that the operating model may change over time based on experience and shifts in priorities. For example, an agency may begin with a Centralized-Facilitated approach and then switch to the Centralized-Command and Control approach if they identify the need for more “teeth” to effect the desired changes in behavior.

Agile Values

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

Source: The Agile Manifesto

Agile Data Governance

There is growing interest in the concept of “Agile Data Governance”, which is an incremental, bottom-up approach to data governance, analogous to Agile software development. Proponents of this approach argue that traditional top-down data governance models (1) are not flexible enough to respond to changing data and analytics needs and priorities and (2) fail to achieve high-levels of adoption or desired changes in practices.

Following an Agile approach allows an agency to view data governance as a continuous improvement process. Begin by reviewing what the agency is already doing and identifying ways to build on these successes – by expanding

their scope or replicating them across different parts of the agency. Look for quick wins as well as opportunities to learn from prior activities that didn’t go as well as expected. Keep in mind that a customer orientation is central to the Agile philosophy. Data governance in a DOT has multiple customers – including data managers, producers and users. Each data governance initiative should clearly identify the customers and focus on meeting their needs in the most expeditious way possible.

Data Governance Artifacts

Examples of data governance artifacts that might be created through business-driven data improvement engagements:

- Data privacy and security classifications

- Dataset metadata/data catalog entries

- Business definitions for data elements (data dictionaries)

- Data lineage diagrams

- Data retention schedules

- Busienss rules

- Data quality management processes

- Data sharing agreements

- Data update responsibilities and processes

Figure 3 illustrates an Agile data governance (DG) process. It is characterized by starting with a minimal viable data governance capability and then building this capability opportunistically through activities that directly add value through increasing access to and use of data.

Initial steps are:

- Minimum Viable Data Governance Capability. Establish a minimum viable capability for data governance. This might consist of a data governance lead and a few support staff resources, some basic principles and guidelines, and a few foundational tools and templates.

- Backlog of Initiatives. Based on the goals and gaps you have identified for data governance, create and prioritize a data governance “backlog”, consisting of short duration efforts that would help to close the gaps between your current and target state for data governance. This backlog might include activities such as creating a data classification process or creating an example and template for documenting data lineage.

These are then followed by a cyclical process of:

- Business-Driven Engagements. Seek opportunities to accomplish your backlog initiatives in conjunction with business-driven data

- improvement projects. These might include efforts to bring new data into the agency, create new reporting data sources, or get data ready for system modernization projects. Embed data governance staff and integrate data governance activities and artifact creation within these projects.

- Feedback and Lessons. Following each business engagement, seek feedback from participants and identify lessons about what was most effective and what needs improvement.

- Updated Guidance, Standards and Processes. Use what was produced as part of the business engagements and the lessons learned to update and augment the data governance guidance, standards, processes and other support materials that you have created. Create a library of example artifacts that others can build on.

- Dissemination/Education. Conduct outreach and training activities to make people aware of any updated guidance, standards, and processes.

- Identify Opportunities and Document Successes. Based on the business engagements, identify opportunities to apply what was created and learned. Document accomplishments and value added.

- Update the Backlog. Update the backlog based on accomplishments, re-prioritize remaining items based on what was learned, and seek out the next set of business engagements.

Option 3 – Decentralized-Coordinated by an Operating Unit above is most compatible with the Agile approach, though elements of Agile data governance can be applied with any of the operating models.

Level of Change

To have an impact, all data governance programs must make some level of changes to the organization. The question to consider is: how much change is the agency prepared to take on – at least initially? Attempting major changes to roles, responsibilities, processes and requirements before there is sufficient management support or appetite for these changes can put the entire effort at risk of failure. On the other hand, being overly cautious about making any changes to the status quo is unlikely to achieve the desired results.

Options to consider for the initial level of change to pursue are:

- Option 1-Low. Minor, incremental changes to existing roles and processes, with an emphasis on education and support to achieve data governance goals.

- Option 2-Medium. Limited, selective changes to existing roles and processes focused primarily on data governance sponsors,

- champions and stewards. Existing management structures and processes are leveraged where possible.

- Option 3-High. Major changes to data management oversight responsibilities, decision-making authority, roles, processes, practices, and tools. Requires changes in behavior for data managers, producers, and consumers across the organization.

Most agencies will choose the middle ground option – leveraging existing management and decision-making processes to the greatest extent possible, but adding “just enough” new processes and role definition needed to achieve the goals that have been established. Another approach is to begin with Option 1 and pursue incremental changes, assess results, and then move on to more significant changes (Option 2 and then 3).

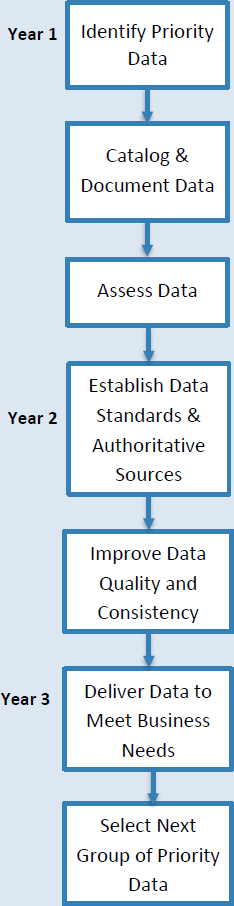

Step 7: Create a Roadmap

Once the initial approach to data governance has been selected, it is helpful to create a roadmap that lays out the major activities or initiatives to be pursued over the next 3-5 years.

Purpose of a Roadmap. Developing a roadmap provides an opportunity to:

- Set priorities—data governance is a long-term endeavor and there are important choices to be made about what to do first – and what to tackle later. Priorities can be based on qualitative judgement or a more rigorous quantitative Return-on-Investment (ROI) analysis.

- Account for dependencies—some activities need to be completed before others. It is important to plan for a logical sequencing of activities.

- Ensure coordination with other efforts—there may be a need to coordinate timing of data governance implementation activities with other agency initiatives such as strategic planning efforts or major system replacement projects. In addition, there may be a need to meet timelines associated with externally driven requirements associated with state-level data governance rules or new reporting expectations.

- Account for resource constraints and management decision-making—consider the capacity of the data governance lead and the stakeholder group to conduct and oversee activities, and the time required for senior managers to approve new policies or other changes. Even when consultant support is used, there are limits to how much can be accomplished within a given timeframe.

Once complete, a roadmap is a valuable tool for communicating to the full range of stakeholders about the planned implementation approach. It helps to set expectations about what is going to happen and when – and tells people when they might need to get engaged.

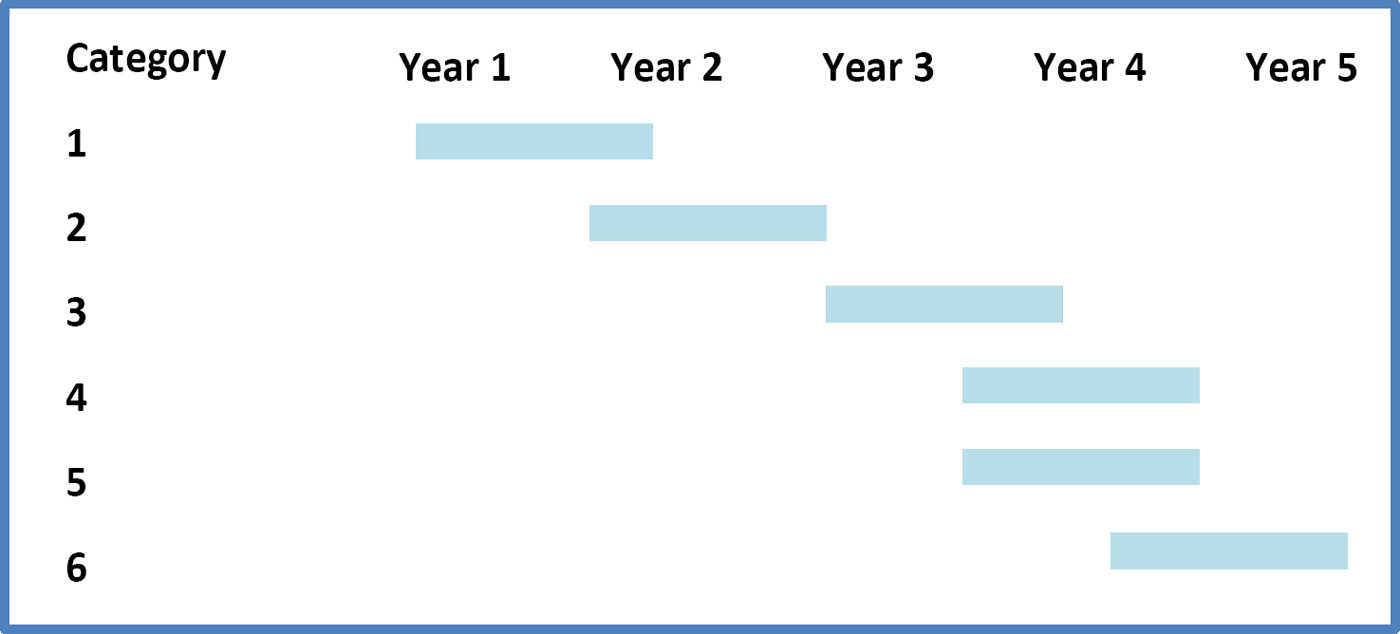

Roadmap Content and Organization. The roadmap should include a high-level view that can fit on a single page of the sequence of activities to be conducted. One common format (illustrated in Figure 4) is to show a timeline across the top, and category of activities horizontally.

Roadmap for Incremental Data Improvement & Delivery

This high-level view can be supplemented by a further breakdown of what is included in each major category.

The content of the roadmap will depend on the results of your assessment, the gaps to be addressed, and the selected operating model and scope. See the sidebar for one example.

In developing the roadmap, consider the following options:

- An incremental but broad-based approach – moving forward in parallel on multiple initiatives at once;

- An incremental but focused approach – moving forward with a single initiative at time; or

- A “big bang” approach – to make significant progress on multiple fronts within the roadmap time horizon (typically using consultant resources).

Roadmap Updates. The roadmap should be updated regularly (nominally on an annual basis) to reflect the speed of progress, identification of new priority activities and emerging external factors. The executive sponsor should approve the initial roadmap and any changes to the roadmap.

Step 8: Create an Action Plan

The Action Plan is created based on the roadmap. It defines the specific, implementable activities at a sufficient level of granularity to enable you to:

- Estimate resource needs for each action

- Assign the action to a lead person

- Identify the products or outputs of the action

- Identify the predecessor(s) of the action

- Track the status of the action (planned, in progress, complete, deferred/eliminated)

Action Planning Pitfalls to Avoid

- Overly ambitious plan not consistent with available resourcing

- Not specific enough to tell when an action is complete

- Too detailed – not enough flexibility to adapt

- Too many actions - hard to track and communicate status

- Failure to update the action plan regularly and use as a living document

- Failure to assign the task of updating the plan to a specific individual or group

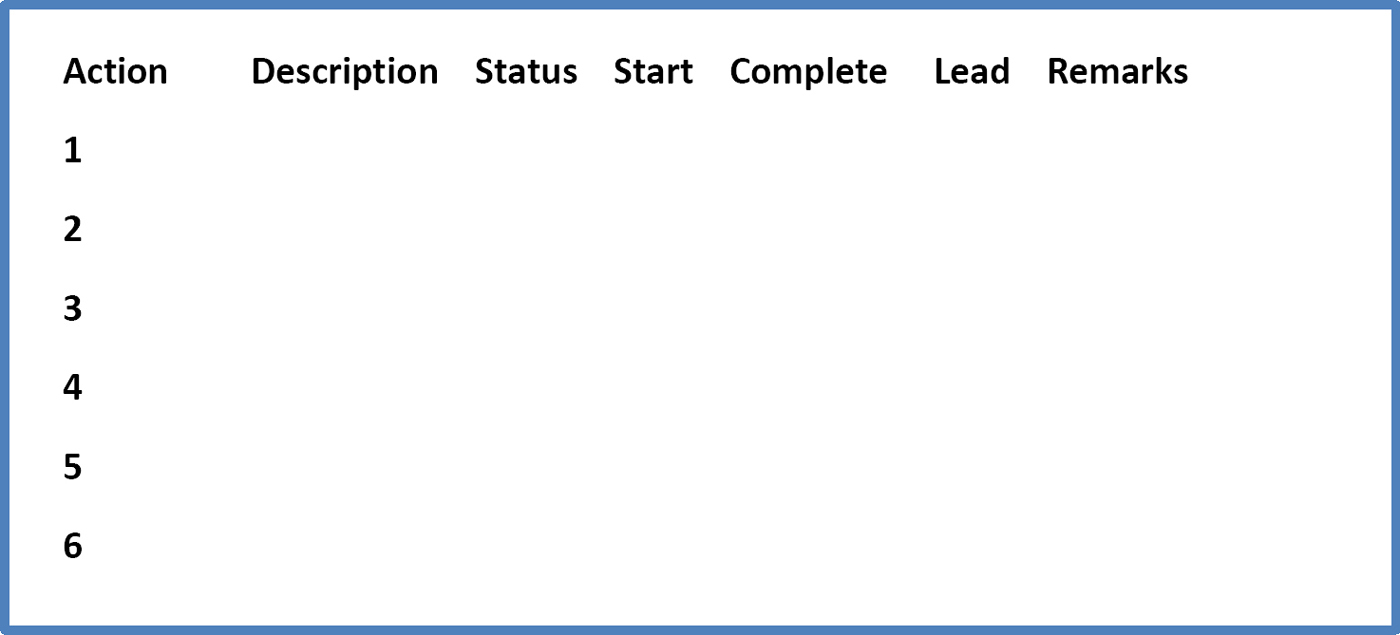

However, avoid being overly prescriptive. Allow for some flexibility on the part of the leads to tailor the actions based on stakeholder input and other factors. Avoid having too many actions in your plan; it can set unrealistic expectations and create a burden for tracking and communicating progress. Figure 5 illustrates a simple action plan format.

Treat the Action Plan as a living document. Update it on at least a monthly basis to record action initiation or completion, changes to the scope or timing of existing actions, and inclusion of new actions to meet priorities and opportunities that arise. Keep notes on the next steps to be taken for each action so that you can keep things moving.

The Action Plan can be used to develop briefing materials for your governance groups and other stakeholders to keep them informed about what is happening and the progress being made.

One initial action to consider in the Action Plan is to establish an initial data governance policy that describes the purpose and scope of data governance and the roles and responsibilities of data governance bodies and stewards. This provides an official endorsement and can serve as a foundation for specific data governance initiatives. Each initiative in the Action Plan should be documented through a procedure, practice document or guidance document.

![]() See Chapter 7 for a sample Data Governance Policy outline.

See Chapter 7 for a sample Data Governance Policy outline.

Step 9: Implement, Monitor and Adjust

Move forward with establishing roles and groups (Chapter 4) and implementing one or more initiatives (Chapter 5). As part of this activity, set aside some time each month to review accomplishments, results and any lessons learned. Keep a chronology of key milestones (such as policy adoption, governance body chartering, data catalog rollout). Keep a list of challenges and

opportunities based on interactions with stakeholders and any roadblocks encountered.

One DOT’s Data Governance Chronology

This chronology illustrates how data governance is a marathon, not a sprint.

2015 – Initiated data business planning effort

2016 – Plan completed, data governance work group set up to recommend approach

2017- Leadership team accepted work group’s recommendations

2017-2018 – Outreach conducted to share the recommendations with key stakeholder groups

2018 - Formal Data Governance Policy signed by agency director

2019 – First data governing body chartered; stewardship model developed and approved by agency leadership

2020-Transition to a new governance structure responsible for both technology and data governance (with a sub-group for data)

2021-Data governance issue tracking and resolution process established

2022-First Chief Data Officer hired; new data office established

Use this information for the next cycle of planning and adjustment of the roadmap and action plan. Key questions to ask as you do this are:

- What have we accomplished? What are our major “wins” so far? Have we recorded and communicated these to leadership?

- What is taking more time than anticipated? Why?

- What can be done to remove barriers that are preventing progress?

- What impact do delays have on the planned completion dates for our major milestones?

- Are there any new federal or state-level activities/requirements, changes in agency priorities, or emerging agency initiatives that may affect priorities and approaches for data governance?

- What opportunities are there for working with “early adopter” business units to test and provide models of data governance processes or artifacts – for example, data dictionaries, data sharing agreements, or quality management plans.

- What opportunities are there to respond to feedback we have received from stakeholders and customers?

As data governance matures, work on improving techniques for monitoring and reporting on the value that is being delivered to the organization.

Ohio DOT’s ROI Model for Data Governance

The Ohio DOT (ODOT) engaged a consultant to quantify its return on investment (ROI) from a variety of data governance activities under its Transportation Asset Management Plan (TAMP). The effort began with recognition that it is often difficult to quantify benefits from data management or data improvement efforts.

The consultant developed several business cases, each starting with a base case described by a set of parameters and costs (actual and estimated for subsequent years). Next, for each case, the consultant developed actual and estimated savings as “cash flow” that could be used in the ROI calculations. The calculated savings were based on labor and acquisitions related to each of the business cases and the improvements related to data governance generating savings that would accrue to the agency through greater efficiency, cost avoidance, and reduced liability. ODOT can track performance annually and compare estimated versus actual ROI for each case to determine if it is achieving the expected value from each of its measured activities.

ROI in data governance can be challenging to measure. There are ways, of course, to measure data quality, and the dollars spent on data improvement can be tracked. However, it is still often difficult to make the link between better data and the agency’s bottom lines of performance management: mobility, safety, and the state of good repair of its infrastructure. Developing

methods to report those links is worth some effort because data governance is a formal way of managing and accessing data assets that results in tangible benefits to the agency.

Summary

Implementing data governance is an iterative process involving stakeholder engagement, education, goal setting, assessment of the agency’s current state and gaps, scoping of an initial approach, and then planning the actions to be pursued over a 3–5-year period. As you move forward with implementation using the resources in the remainder of this Guide, be sure to reflect on lessons learned and modify the plan accordingly.