1

Introduction

The radio frequency spectrum is a limited resource for which there is an ever-increasing demand from an expansive range of applications—from commercial (such as mobile phones), through governmental (emergency communications, defense, etc.), to scientific (such as hurricane monitoring from space and measuring properties of remote galaxies). The radio spectrum is conventionally defined as the part of the electromagnetic spectrum including frequencies up to 3000 GHz.1 However, use of radio technology now extends to frequencies approaching the infrared part of the spectrum. The selection of a frequency band for a particular use depends on many factors, including propagation characteristics, atmospheric attenuation, technological capabilities, and cost. Changing the band of operation is not always possible. This is particularly the case for science applications, which include passive observations of the cosmos for radio astronomy and both active and passive observations for Earth remote sensing. In many cases, key observations are only possible in specific frequency bands. In remote sensing, these fre-

___________________

NOTE: This “Introduction” is an updated version of that given in National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022, Views of the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on Agenda Items of Interest to the Science Services at the World Radiocommunication Conference 2023, The National Academies Press, which was updated from previous National Academies’ reports.

1 See Article 2, Section I in International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2020, “Radio Regulations,” Edition of 2020, https://www.itu.int/pub/R-REG-RR-2020.

quency bands are dictated by the spectral signatures of various Earth parameters, including atmospheric temperature, humidity, cloud particles, precipitation, and composition; sea-surface temperature, topography, winds, and salinity; soil moisture; vegetation health; and cryosphere properties. In the case of radio astronomy, bands are often dictated by particular transition frequencies of atoms and molecules (as is also the case with Earth atmospheric composition and temperature sounding), which are established by the laws of nature.

Use of the radio spectrum is regulated worldwide by an international treaty-level agreement, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Radio Regulations (RR).2 The ITU Radiocommunication Sector (ITU-R) takes the lead on issues related to the RR. In the RR, spectrum users are divided into different categories, which are referred to as radiocommunication “services.” Examples of these services include the broadcasting service, radionavigation-satellite service (RNSS; used for Global Positioning System and Global Navigation Satellite Service types of navigation), space research service (SRS; for example, the NASA Deep Space Network used to communicate with spacecraft beyond Earth orbit), mobile service, mobile-satellite service (MSS, used for communications between orbiting satellites and mobile ground stations), and Earth exploration-satellite service (EESS, used for spaceborne passive or active Earth remote sensing and data relay to and from those spacecraft). In the RR, the radio astronomy service (RAS) is classified as a radio service but not a radiocommunication service, because radio astronomy involves passive reception only, with no active transmission of radio frequency signals. RAS is the only service so distinguished. Other radio services can be active or passive, depending on whether they transmit and receive, or receive only. EESS can be dedicated specifically to active or passive remote sensing, and these two uses are distinguished in the regulations (in addition, some bands are used for transmission of EESS data and/or EESS spacecraft telemetry, tracking, and control and are typically annotated with “space-to-Earth” or “Earth-to-space” qualifiers). The EESS (passive) services use receivers to measure natural radio frequency emissions from the oceans, land, ice, and atmosphere (including severe weather phenomena such as tropical storms). Active (i.e., transmitting) sensors in EESS (active) are used for measuring winds, soil moisture, precipitation, cloud particles, and more. In the case of radio astronomy,

___________________

2 See ITU, 2024, “Radio Regulations,” Edition of 2024, https://www.itu.int/pub/RREG-RR. Regulatory documents referred to throughout this report are listed in Appendix D.

celestial sources, such as objects in the solar system, stars, the interstellar medium, galaxies, and other celestial bodies, are observed always in a receive only (passive) mode. Consequently, as noted above, RAS is defined in the RR exclusively as a passive service. While RAS is a passive-only service, astronomers also use powerful radars to study the surface and other properties of asteroids and the planets and their satellites, including radar observations to detect near Earth objects (NEOs). Such radar astronomy is considered part of the radiolocation service (RLS) and is subject to its regulations.

Radio telescopes and passive EESS sensors measure the natural emissions from targets under study. A bright celestial radio source presents a spectral power flux-density (spfd) of order −260 dB(W/m2 Hz), and radio astronomers routinely detect emissions even four to six orders of magnitude fainter than this. The high sensitivity required for these observations makes RAS observatories vulnerable to interference from in-band, out-of-band, and spurious (e.g., harmonic) emissions from licensed and unlicensed users of neighboring bands. Weak signals that are unintended byproducts of human activity can obstruct the scientific uses of the spectrum. Remote-sensing satellite sensors observe the extremely weak natural emission from Earth’s surface and atmosphere. These observations are similarly very vulnerable to interference from unintended human transmissions. Recommendations ITU-R RA.769-2 and ITU-R RS.2017-0 contain the threshold levels of interference considered harmful to the use of the radio spectrum by RAS and EESS (passive), respectively.

Both EESS (passive) and RAS involve making precise measurements of naturally occurring radio emissions from physical phenomena. These signals are typically very small, owing to the feeble strength of these natural emissions, the large distance between the source and observer, or a combination of the two. Importantly, the scientific information obtained derives from yet smaller variations in those already small signals. Such variations convey information such as details of the cosmic microwave background (CMB)—giving insights into the nature of the early universe—or on changes in sea-surface temperature (enabling tracking of tropical storm formation or decadal-scale climate change signatures). Given the need for accuracy and precision of such observations, stringent protections from radio frequency interference (RFI) are needed. For both EESS (passive) and RAS, a cornerstone of this protection is the establishment of fixed spectral bands where emissions from other services are limited or, in many cases, prohibited. Particular attention needs to be paid to limits on out-of-band emissions (OOBE)—leakage beyond

the band assigned for transmission—in cases where other services are authorized to transmit in regions adjacent to these protected bands. In the case of RAS, additional protection is often sought by placing observatories in remote locations. Further protection is often accomplished by establishing radio frequency coordination zones in the immediate area. Such geographical protection and coordination approaches are well established for limiting interference from ground-based transmissions. However, there is an increasing need to extend such geographical-based coordination to include protection from airborne and space-based transmissions, which would otherwise undermine the benefits accrued (typically at great cost) by locating observatories in remote locations.

Scientific users understand the need to share the spectrum between active and passive users, but it is important to note that some sharing techniques that work for active services do not necessarily work for passive uses. For example, dynamic spectrum management, where radio frequency monitoring is used to identify “unused” parts of the spectrum, is not an appropriate method to share the spectrum with a passive service that has no radio signature to detect. On the other hand, in certain cases spatial or temporal separation may be used to share the spectrum effectively between active and passive services within the framework of the RR. This is typically accomplished by sharing real-time operational data.

A factor that needs to be considered in many cases is “aggregate interference,” especially when dealing with spectrum users such as low-power radio frequency transmitting (active) devices that do not require an individual license and that are designed to be used by thousands or even millions of users at a given moment. For example, wireless mobile handsets and radars mounted on vehicles are two increasingly numerous potential sources of RFI. Whereas emissions from one such transmitter might fall below threshold levels of interference for a radio astronomy or remote sensing receiver, the sum of many such transmitters may not. It is essential to account for such aggregation when computing the total power from all transmitters that have the potential to reach the protected passive EESS sensor or radio astronomy receiver. It is important to note that the threshold levels for harmful interference to RAS and EESS (passive) (listed in Recommendations ITU-R RA.769-2 and ITU-R RS.2017-0, respectively) should be considered in the aggregate, not for a single transmitter.

Strong interference corrupts observations in clearly recognizable ways, and affected data can be excised. However, this comes at the cost of reducing the number of available measurements and thus the available information for both EESS (passive) and RAS. Such inter-

fering transmissions have been and need to be strongly discouraged; when they violate the RR or national regulations, their cessation may be legally required. In principle, very weak levels of interference can be tolerated if they genuinely have no impact on the scientific measurements. The greatest level of threat comes from RFI that is not sufficiently strong to be readily identified in, and excised from, the scientific instrument’s data streams, yet is still strong enough to corrupt the scientific measurement. For Earth remote sensing, this could, for example, result in incorrect information being ingested into weather forecasting systems, undermining the reliability and value of their predictions. Similarly, for RAS, incorrect attribution of such emissions to astronomical sources can lead to erroneous scientific conclusions.

Since radio waves do not stop at national borders, international regulation is necessary to ensure effective use of the radio spectrum for all parties. The ITU has as its mission the facilitation of the efficient and interference-free use of the radio spectrum. One of the most important functions of the ITU is to maintain the International Table of Frequency Allocations, an article within the RR document. Every country has sovereign authority to allocate uses of the radio frequency spectrum within its borders but most choose to follow the International Table of Frequency Allocations out of convenience and to avoid potential interference to their neighbors. Every few years (currently every 4 years), the ITU convenes a World Radiocommunication Conference (WRC) to review and revise the RR. Changes to the RR are formulated through proposals to the conference according to agenda items, which are agreed on at the previous WRC. Sovereign governments or “Member States” (with their respective regulatory bodies referred to within the ITU as “administrations”) and academic, industrial, and scientific organizations (referred to within the ITU as “members” with lowercase “m”) participate in the WRC, but only the more than 190 Member States (administrations) of the ITU are entitled to introduce proposals and to vote (either as individual administrations, or as part of regional groups, see below).

In the period between WRCs, administrations work internally and with their regional counterparts to develop a consensus position on each agenda item, to the extent possible, given varying national priorities and interests. The national delegations then submit proposals to the WRC and negotiate with other delegations before adoption of each proposal. Much of this negotiation takes place between regional groups—for example, the European Post and Telecommunications Conference (CEPT), with more than 40 members, or the Inter-American Telecommunications Commission

(CITEL), which has more than 30 members. The outcome of a WRC, a revision of the RR, is an international treaty.

Agenda items are typically very specific and propose substantial changes to the use of the spectrum that can have a significant impact on services. To ensure their continued ability to access the radio spectrum for scientific purposes, scientists need to participate in the discussions leading up to each WRC (the next of which is WRC-27, currently scheduled to be held in 2027). Indeed, the fact that more than 95 percent of the spectrum allocations below 3 GHz are for active users underscores how important it is that the vulnerable passive services participate in the process and express their concerns about potential adverse effects on their operations.3 By request of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Committee on the Views on the World Radiocommunication Conference 2027 was convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to provide guidance to U.S. spectrum managers and policymakers preparing for WRC-27 as to how to ensure the protection of the scientific exploration of Earth and the universe using the radio spectrum (see Appendix A for the committee’s statement of task). While the resulting document is targeted primarily at U.S. agencies dealing with radio spectrum issues, other administrations and foreign scientific users may find its recommendations useful in their own WRC planning.

Referring to ITU-R Resolution 813 (WRC-23),4 the committee identified the WRC-27 agenda items of relevance to U.S. radio astronomers and Earth remote sensing researchers, along with preliminary agenda items of relevance for WRC-31.5 The agenda items are discussed in numerical order to facilitate locating a specific one, for easy perusal. The committee has determined that many outcomes of the agenda items shown in Tables 1-1 and 1-2 may impact

___________________

3 In the United States, the radio astronomy service (RAS) and the Earth exploration-satellite service (EESS) are allocated 2.07 percent of the spectrum on a primary basis and 4.08 percent of the spectrum on a secondary basis below 3 GHz. Allocations for RAS and EESS are comparable in the ITU’s international allocation tables. From National Research Council, 2010, Spectrum Management for Science in the 21st Century, The National Academies Press, pp. 137–138.

4 See “Resolution 813 (WRC-23) Agenda for the 2027 World Radiocommunication Conference” in International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2023, World Radiocommunication Conference 2023 (WRC-23) Final Acts, http://handle.itu.int/11.1002/pub/8225d4fb-en.

5 See “Resolution 814 (WRC-23) Preliminary Agenda for the 2031 World Radiocommunication Conference” in ITU, 2023, World Radiocommunication Conference 2023 (WRC-23) Final Acts.

TABLE 1-1 Agenda Items Under Consideration for the 2027 World Radiocommunication Conference

| 1.1 | Consider the technical and operational conditions for the use of the frequency bands 47.2-50.2 GHz and 50.4-51.4 GHz (Earth-to-space), or parts thereof, by aeronautical and maritime earth stations in motion communicating with space stations in the fixed-satellite service and develop regulatory measures, as appropriate, to facilitate the use of the frequency bands 47.2-50.2 GHz and 50.4-51.4 GHz (Earth-to-space), or parts thereof, by aeronautical and maritime earth stations in motion communicating with geostationary space stations and non-geostationary space stations in the fixed-satellite service, in accordance with Resolution 176 (Rev.WRC-23). |

| 1.2 | Consider possible revisions of sharing conditions in the frequency band 13.75-14 GHz to allow the use of uplink fixed-satellite service earth stations with smaller antenna sizes, in accordance with Resolution 129 (WRC-23). |

| 1.3 | Consider studies relating to the use of the frequency band 51.4-52.4 GHz to enable use by gateway earth stations transmitting to non-geostationary-satellite orbit systems in the fixed-satellite service (Earth-to-space), in accordance with Resolution 130 (WRC-23). |

| 1.4 | Consider a possible new primary allocation to the fixed-satellite service (space-to- Earth) in the frequency band 17.3-17.7 GHz and a possible new primary allocation to the broadcasting-satellite service (space-to-Earth) in the frequency band 17.3-17.8 GHz in Region 3, while ensuring the protection of existing primary allocations in the same and adjacent frequency bands, and to consider equivalent power flux-density limits to be applied in Regions 1 and 3 to non-geostationary-satellite systems in the fixed-satellite service (space-to-Earth) in the frequency band 17.3-17.7 GHz, in accordance with Resolution 726 (WRC-23). |

| 1.5 | Consider regulatory measures, and implementability thereof, to limit the unauthorized operations of non-geostationary-satellite orbit earth stations in the fixed-satellite and mobile- satellite services and associated issues related to the service area of non-geostationary-satellite orbit satellite systems in the fixed-satellite and mobile-satellite services, in accordance with Resolution 14 (WRC-23). |

| 1.6 | Consider technical and regulatory measures for fixed-satellite service satellite networks/systems in the frequency bands 37.5-42.5 GHz (space-to-Earth), 42.5-43.5 GHz (Earth-to-space), 47.2-50.2 GHz (Earth-to-space) and 50.4-51.4 GHz (Earth-to-space) for equitable access to these frequency bands, in accordance with Resolution 131 (WRC-23). |

| 1.7 | Consider studies on sharing and compatibility and develop technical conditions for the use of International Mobile Telecommunications (IMT) in the frequency bands 4 400-4 800 MHz, 7 125-8 400 MHz (or parts thereof), and 14.8-15.35 GHz taking into account existing primary services operating in these, and adjacent, frequency bands, in accordance with Resolution 256 (WRC-23). |

| 1.8 | Consider possible additional spectrum allocations to the radiolocation service on a primary basis in the frequency range 231.5-275 GHz and possible new identifications for radiolocation service applications in the frequency bands within the frequency range 275-700 GHz for millimetric and sub-millimetric wave imaging systems, in accordance with Resolution 663 (Rev.WRC-23). |

| 1.9 | Consider appropriate regulatory actions to update Appendix 26 to the Radio Regulations in support of aeronautical mobile (OR) high frequency modernization, in accordance with Resolution 411 (WRC-23). |

| 1.10 | Consider developing power flux-density and equivalent isotropically radiated power limits for inclusion in Article 21 of the Radio Regulations for the fixed-satellite, mobile-satellite and broadcasting-satellite services to protect the fixed and mobile services in the frequency bands 71-76 GHz and 81-86 GHz, in accordance with Resolution 775 (Rev.WRC-23). |

| 1.11 | Consider the technical and operational issues, and regulatory provisions, for space-to- space links among non-geostationary and geostationary satellites in the frequency bands 1 518-1 544 MHz, 1 545-1 559 MHz, 1 610-1 645.5 MHz, 1 646.5-1 660 MHz, 1 670-1 675 MHz and 2 483.5-2 500 MHz allocated to the mobile-satellite service, in accordance with Resolution 249 (Rev.WRC-23). |

| 1.12 | Consider, based on the results of studies, possible allocations to the mobile-satellite service and possible regulatory actions in the frequency bands 1 427-1 432 MHz (space-to-Earth), 1 645.5-1 646.5 MHz (space-to-Earth) (Earth-to-space), 1 880-1 920 MHz (space-to-Earth) (Earth- to-space) and 2 010-2 025 MHz (space-to-Earth) (Earth-to-space) required for the future development of low-data-rate non-geostationary mobile-satellite systems, in accordance with Resolution 252 (WRC-23). |

| 1.13 | Consider studies on possible new allocations to the mobile-satellite service for direct connectivity between space stations and International Mobile Telecommunications (IMT) user equipment to complement terrestrial IMT network coverage, in accordance with Resolution 253 (WRC-23). |

| 1.14 | Consider possible additional allocations to the mobile-satellite service, in accordance with Resolution 254 (WRC-23). |

| 1.15 | Consider studies on frequency-related matters, including possible new or modified space research service (space-to-space) allocations, for future development of communications on the lunar surface and between lunar orbit and the lunar surface, in accordance with Resolution 680 (WRC-23). |

| 1.16 | Consider studies on the technical and regulatory provisions necessary to protect radio astronomy operating in specific Radio Quiet Zones and, in frequency bands allocated to the radio astronomy service on a primary basis globally, from aggregate radio-frequency interference caused by non-geostationary-satellite orbit systems, in accordance with Resolution 681 (WRC-23). |

| 1.17 | Consider regulatory provisions for receive-only space weather sensors and their protection in the Radio Regulations, taking into account the results of ITU Radiocommunication Sector studies, in accordance with Resolution 682 (WRC-23). |

| 1.18 | Consider, based on the results of ITU Radiocommunication Sector studies, possible regulatory measures regarding the protection of the Earth exploration-satellite service (passive) and the radio astronomy service in certain frequency bands above 76 GHz from unwanted emissions of active services, in accordance with Resolution 712 (WRC-23). |

| 1.19 | Consider possible primary allocations in all Regions to the Earth exploration-satellite service (passive) in the frequency bands 4 200-4 400 MHz and 8 400-8 500 MHz, in accordance with Resolution 674 (WRC-23). |

NOTE: Acronyms are defined in Appendix C.

SOURCE: Direct quotes from agenda items in “Resolution 813 (WRC-23) Agenda for the 2027 World Radiocommunication Conference” in International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2023, World Radiocommunication Conference 2023 (WRC-23) Final Acts, http://handle.itu.int/11.1002/pub/8225d4fb-en, following ITU conventions for frequency designation (see “Conventions for Specifying Frequencies” section in Chapter 1).

TABLE 1-2 Preliminary Agenda Items Under Consideration for the 2031 World Radiocommunication Conference

| 2.1 | Consider potential new allocations to the fixed, mobile, radiolocation, amateur, amateur-satellite, radio astronomy, Earth exploration-satellite (passive and active) and space research (passive) services in the frequency range 275-325 GHz in the Table of Frequency Allocations of the Radio Regulations, with the consequential update of Nos. 5.149, 5.340, 5.564A and 5.565, in accordance with Resolution 721 (WRC-23). |

| 2.2 | [Consider the possible (frequency bands) for (non-beam and beam) wireless power transmission to avoid harmful interference to the radiocommunication services caused by wireless power transmission, in accordance with Resolution 910 (WRC-23)]. |

| 2.3 | Consider the use of aeronautical and maritime earth stations in motion communicating with non-geostationary space stations in the fixed-satellite service (Earth-to-space) in the frequency band 12.75-13.25 GHz, in accordance with Resolution 133 (WRC-23). |

| 2.4 | Consider, based on the results of ITU Radiocommunication Sector studies, support for inter-satellite service allocations in the frequency bands 3 700-4 200 MHz and 5 925-6 425 MHz, and associated regulatory provisions, to enable links between non-geostationary orbit satellites and geostationary orbit satellites, in accordance with Resolution 683 (WRC-23). |

| 2.5 | Consider a possible primary allocation in the frequency bands [694-960 MHz, or parts thereof, in Region 1], 890-942 MHz, or parts thereof, in Region 2, and [3 400-3 700 MHz, or parts thereof, in Region 3] to the aeronautical mobile service for the use of International Mobile Telecommunications (IMT) user equipment in terrestrial IMT networks by non-safety applications, in accordance with Resolution 251 (Rev.WRC-23). |

| 2.6 | Consider the identification of the frequency bands [102-109.5 GHz, 151.5-164 GHz, 167-174.8 GHz, 209-226 GHz and 252-275 GHz] for International Mobile Telecommunications, in accordance with Resolution 255 (WRC-23). |

| 2.7 | Consider improving the utilization of VHF maritime radiocommunication, in accordance with Resolution 363 (Rev.WRC-23). |

| 2.8 | Consider improving the utilization and channelization of maritime radiocommunication in the MF and HF bands, including potential revisions of Article 52 and Appendix 17, in accordance with Resolution 366 (WRC-23). |

| 2.9 | Consider possible allocations to the radionavigation-satellite service (space-to-Earth) in the frequency bands [5 030-5 150 MHz and 5 150-5 250 MHz] or parts thereof, in accordance with Resolution 684 (WRC-23). |

| 2.10 | Consider a possible new primary allocation to the Earth exploration-satellite service (Earth-to-space) in the frequency band 22.55-23.15 GHz, in accordance with Resolution 664 (Rev.WRC-23). |

| 2.11 | Consider an upgrade of the secondary allocation to the Earth exploration-satellite service (space-to-Earth) in the frequency band [37.5-40.5 GHz] or possible new worldwide frequency allocations on a primary basis to the Earth exploration-satellite service (space-to-Earth) in certain frequency bands within the frequency range [40.5-52.4 GHz], in accordance with Resolution 685 (WRC-23). |

| 2.12 | Consider possible new allocations to the Earth exploration-satellite service (active) in the frequency bands [3 000-3 100 MHz] and [3 300-3 400 MHz] on a secondary basis, in accordance with Resolution 686 (WRC-23). |

| 2.13 | Consider studies on coexistence between spaceborne synthetic aperture radars operating in the Earth exploration-satellite service (active) and the radiodetermination service in the frequency band 9 200-10 400 MHz, with possible actions as appropriate, in accordance with Resolution 772 (WRC-23). |

| 2.14 | Review spectrum use and needs of applications of broadcasting and mobile services and consider possible regulatory actions in the frequency band 470-694 MHz or parts thereof, in accordance with Resolution 235 (Rev.WRC-23). |

NOTE: Acronyms are defined in Appendix C.

SOURCE: Direct quotes from preliminary agenda items in “Resolution 814 (WRC-23) Preliminary Agenda for the 2031 World Radiocommunication Conference” in International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2023, World Radiocommunication Conference 2023 (WRC-23) Final Acts, http://handle.itu.int/11.1002/pub/8225d4fb-en, following ITU conventions for frequency designation (see “Conventions for Specifying Frequencies” section in Chapter 1).

RAS and EESS operations, and it has provided the reasons for its views, as well as the scientific application of the bands that may be impacted. Potential impacts are assessed based on criteria related to in-band, out-of-band, and spurious emissions, as appropriate, as noted in each discussion.

To provide context for the potential scientific impact of these agenda items, a brief overview of some of the scientific results derived from the passive use of the radio spectrum by EESS and RAS is described below. A more complete view of both the scientific uses and the frequency allocations in the radio spectrum can be found in Handbook of Frequency Allocations and Spectrum Protection for Scientific Uses: Second Edition.6

EARTH EXPLORATION-SATELLITE SERVICE

Satellite remote sensing is a uniquely valuable resource for monitoring the global atmosphere, land, and oceans. Microwave remote sensing from space is vital for obtaining atmospheric and surface data for the entire planet, particularly when optical remote sensing is blocked by clouds or attenuated by water vapor. Instruments operating in the EESS (passive) and EESS (active) bands provide data that are important to human welfare and security and provide critical information for scientific research, commercial endeavors, and government operations in areas such as defense, security, meteorology, hydrology, agriculture, atmospheric chemistry, climate studies, and oceanography. For example, measurements of ocean temperature and salinity are needed to understand ocean circulation and the associated global distribution of heat and hurricane genesis. Measurements of soil moisture are needed for agriculture and drought assessment, weather prediction (sensible and latent heat exchange with the atmosphere), and for defense (planning military deployments). Passive sensors also provide measurements of atmospheric temperature and humidity, information to monitor changes in the polar ice cover, and data needed for assessing hazards such as hurricanes, wildfires, and drought. For many of these applications, satellite-based radio frequency remote sensing represents the only available method of obtaining atmospheric and surface data across the entire planet. This monitoring is set to become even more important as global climate change drives more extreme weather

___________________

6 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015, Handbook of Frequency Allocations and Spectrum Protection for Scientific Uses: Second Edition, The National Academies Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/21774.

conditions. Major U.S. governmental users of EESS data include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), NSF, NASA, the Department of Defense (DoD), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) of the USDA. Many of these data sets are also freely available to anyone anywhere in the world and, as a result, are widely used for Earth science research and operational forecasting worldwide. Commercial interests in EESS observations continue to grow, with many entities providing value-added data products that have EESS observations in their foundation. Additionally, several companies have launched their own spaceborne missions carrying EESS sensors and are commercializing these observations.

Passive-sensing instruments in space are particularly vulnerable to interference from anthropogenic emissions because they rely on very weak signals emitted naturally from Earth’s surface and atmosphere. Furthermore, because many spaceborne sensors monitor globally and view large swaths of the surface each orbit, they are thus subject to aggregate interference from all emitters in the area scanned. Measurement precision and accuracy is already limited by the available bandwidth, and some of these valuable measurements are being irreversibly contaminated by RFI, even within protected bands. For instance, it is now impossible to retrieve soil moisture from measurements made by the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2) at 6.9 GHz in some areas of the globe due to RFI. Similarly, the Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) and Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) missions, which operate at 1.413 GHz, are adversely impacted by RFI even though they operate in a band specifically allocated for passive use only. Figure 1-1 shows the impact of RFI as observed by the SMAP radiometer.

Thresholds for harmful interference for EESS observations are listed in Recommendation ITU-R RS.2017-0. These thresholds are intended to form the basis of all considerations for acceptable levels of emissions, either in-band or out-of-band, direct-beam or sidelobe, for active services that might affect EESS observations. Particular attention should be paid to the highly variable nature of atmospheric attenuation for a given transmission frequency, driven by a combination of pressure, humidity (i.e., season and/or location), and path (i.e., transmitter location and angle). Strong atmospheric absorption in some spectral regions enables ground-based transmission to proceed in certain key EESS bands with low risk of interference to orbiting sensors. However, airborne transmissions in some of these

SOURCE: P.N. Mohammed, M. Aksoy, J.R. Piepmeier, J.T. Johnson, and A. Bringer, 2016, “SMAP L-Band Microwave Radiometer: RFI Mitigation Prelaunch Analysis and First Year On-Orbit Observations,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 54(10):6035–6047; https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2016.2580459. Copyright © 2016, IEEE. Reprinted with permission from IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing.

same spectral regions would be far less attenuated in the upward direction, and they would render EESS observations of a volume containing such a transmitter unusable. Similarly, ground-based transmissions oriented vertically will be far less attenuated than those aimed horizontally. In many bands, attention is also needed on reflections of ground-based, airborne, or spaceborne transmissions from topography, bodies of water, structures, vehicles, and clouds and precipitation. Thus, reflections of signals from transmitters on geostationary orbit (GSO) are routinely seen by EESS (passive) sensors in low Earth orbits. Similarly, reflections can readily divert some fraction of an otherwise non-interfering horizontally aligned ground-based emission in an upward direction where it may impinge on EESS (passive) observations.

RADIO ASTRONOMY SERVICE

Since radio waves were first detected from a celestial object in 1932, radio astronomy has been an indispensable tool for studying the universe. It is important to realize that radio waves propagate unimpeded in space outside the environment of Earth, and thus the universe is essentially transparent at radio frequencies. This is not true at optical frequencies, with which many objects and phenomena are unobservable due to the absorption by pervasive interstellar dust. For example, the deep interiors of molecular clouds, places where new stars are forming, are completely cloaked by interstellar dust, yet transparent to radio emissions. Thus, radio astronomy observations provide a unique and unfettered view of the universe.

Notable radio astronomy discoveries include the identification of the first planets outside the solar system, which were found circling a distant pulsar. Furthermore, the Nobel Prize–winning discovery of pulsars by radio astronomers has led to the recognition of a widespread population of rapidly spinning neutron stars with gravitational fields at their surface up to 100 billion times stronger than on Earth’s surface. Subsequent radio observations of pulsars have revolutionized the understanding of the physics of neutron stars and have resulted in the first experimental evidence for gravitational radiation, which was recognized with the awarding of another Nobel Prize. More recently, radio astronomy has been used to detect the electromagnetic signals from merging compact objects identified by their gravitational waves, to image the accretion disks around supermassive black holes, and to detect the background gravitational radiation that pervades the universe through its subtle effect on the arrival timing of pulsar signals.

Radio astronomy has also enabled the discovery of organic matter and prebiotic molecules outside our solar system, leading to new insights into the potential existence of life elsewhere in the Milky Way Galaxy. Radio spectroscopy and broadband continuum observations have identified and characterized the birth sites of stars in the Milky Way, the processes by which stars slowly die, and the complex distribution and evolution of galaxies in the universe. Radio observations uncovered the first evidence of the existence of a black hole in our galactic center, a phenomenon that may be crucial to the formation and dynamics of many other galaxies. Thus far, following that discovery, the only images of supermassive black holes and their shadows, in the center of the M87 Galaxy and of our own Milky Way Galaxy, were obtained by an array of radio telescopes. Radio observations of supernovae have allowed astronomers to witness the production of heavy elements essential to the formation of planets like Earth, and of life itself.

Radio astronomy measurements also led to the Nobel Prize–winning discovery of the CMB, the radiation left over from the earliest period in our universe (the Big Bang). Later, exquisitely precise radio observations discovered the weak fluctuations in the CMB of only one-thousandth of a percent, generated in the early universe. Such fluctuations are responsible for the eventual formation of all stars and galaxies we know today, and detailed measurements of them allow cosmologists to constrain the history and eventual fate of our expanding universe. Radio observations of the even more subtle polarization structure of the CMB provide clues into inflationary cosmology and high-energy particle physics. Radio observations have also been used to measure the rotation of external galaxies and provide some of the first evidence of dark matter, which makes up 95 percent of the gravitating matter in the universe.

Radio astronomy also provides valuable information that produces practical benefits to society—for example, by monitoring solar flares and coronal mass ejections (“space weather”). Such monitoring allows for 1- to 4-day forecasts of geomagnetic disturbances that can affect the operation of satellite communications, the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), including the U.S. Global Positioning System (GPS) and other navigation systems, and terrestrial power grids. Techniques developed for high spatial resolution imaging of celestial radio sources are used to determine Earth orientation parameters (EOPs), which describe anomalies in the rotation of Earth due to the changing of distribution of Earth’s mass over time. Such information is essential to the accuracy of GNSSs. In addition, the extreme sensitivity required for observing the very faint sig-

nals from celestial sources poses extraordinary challenges that have demanded highly innovative technology and engineering solutions to overcome. Many of these solutions have proven to be extremely useful in other applications, including the following: optical mapping technology adapted for laser eye surgery; wireless networking technology; sensitive microwave receiving systems, including high-gain antennas and low-noise receivers; cancer detection; time calibration for GPS; and wireless technologies including fast Fourier transform (FFT) chips, solid-state oscillators, frequency multipliers, and cryogenics. Other practical applications include data correlation and recording technology and image restoration techniques, among many others.

It is important to understand the exceedingly weak nature of the typical signals detected by radio telescopes. They can be a million times fainter than the internal receiver noise, and their measurement or even just their detection can require very wide fractional bandwidths and integration times of a day or more. This requirement puts a premium on operating in a very low-noise, low-interference environment. As mentioned above, the threshold levels of interference harmful to radio astronomy observations are listed in Recommendation ITU-R RA.769-2, and these are the levels that have been used to develop these views for issues affecting RAS. It should be emphasized that serious interference can result from weak transmitters even when they are situated in the sidelobes of a radio astronomy antenna (i.e., far-field directions that may lie well outside the main beam of the antenna and toward which its response is non-negligible). Furthermore, radio telescopes are particularly vulnerable to interference from airborne and satellite transmitters, since terrain shielding cannot block the signal from high-altitude emitters. The new large constellations of numerous satellites supporting non-terrestrial communications networks pose a particularly difficult challenge for radio astronomy (as well as for optical astronomy). It needs to be stressed that some of the assumptions used to derive the harmful interference levels in Recommendation ITU-R RA.769-2 break down when dealing with such large constellations because of the large number of satellites expected to be in view at any one time. More restrictive levels may be necessary in the future for the protection of radio astronomy observations in the presence of such satellite constellations.

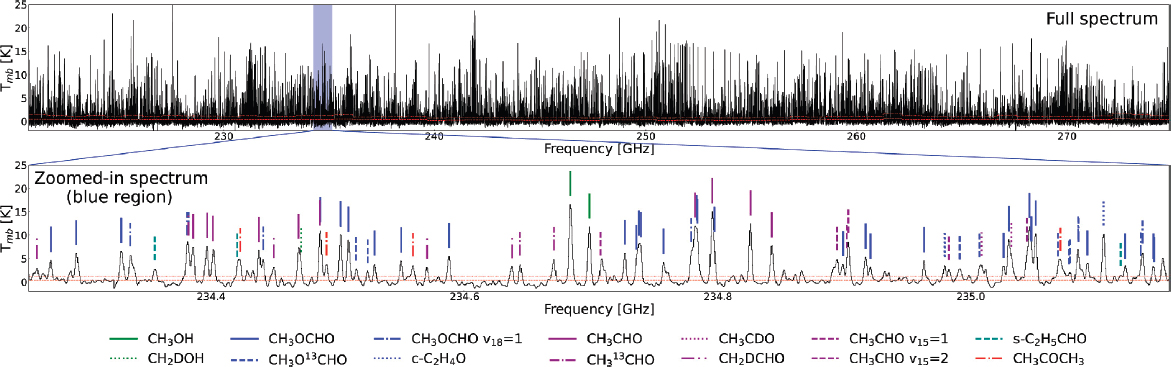

As mentioned above, radio observations of spectral lines require measurements at frequencies determined by the physical and chemical properties of individual atoms and molecules. In particular, knowledge of the chemical makeup of the universe comes through

measurements of spectral lines arising from atomic and molecular transitions, so it is important to protect radio astronomers’ access to the characteristic frequencies of the most important of these, including sufficient bandwidth to measure spectral lines broadened and shifted by thermal and kinematic processes. The emission frequencies of these most important lines are often covered by specific allocations or footnote protections in the United States or International Table of Frequency Allocations. However, it should be stressed that valuable molecular emission lines and the important hydrogen recombination lines occur ubiquitously across the radio spectrum, and these can be essential for gaining insight into the chemical and physical processes at work in a given astrophysical object (Figure 1-2). Furthermore, the expansion of the universe causes spectral lines of distant galaxies to be red-shifted to lower frequencies, with lines from the most distant sources shifted to a small fraction of their rest frequency. Thus, detection of atoms or molecules in distant sources may require measurements to be made at frequencies well below the rest frequency of a line measured in the laboratory. Consequently, observations at spectral frequencies well outside the bands allocated to RAS on a primary or secondary basis are often conducted opportunistically to search for new molecular species and to detect red-shifted spectral lines from distant sources, including from the very early universe. Such usage underscores the value of siting observatories in remote locations and establishing geographical radio coordination zones.

In contrast with the sharp spectral features associated with atomic and molecular spectral lines, certain physical processes such as synchrotron radiation or thermal dust emission give rise to broad band continuum emission. The broad frequency dependence of this continuum spectral emission can be used to identify or disentangle different physical processes at work. Accordingly, observations at multiple frequencies, potentially with wide bandwidths, are needed to characterize the continuum spectra of stars, galaxies, quasars, pulsars, and other cosmic radio sources, and to map the primordial CMB radiation from the early universe. Historically, only narrow bands spaced at approximately one octave separation throughout the spectrum have been given protection at various levels to enable these important continuum spectral studies. Improvements in antenna and receiver design now permit instantaneous fractional bandwidths of 50 percent or more to be used in the latest generation of radio telescopes. This results in considerable improvement in sensitivity over earlier, narrowband systems. Broad bandwidths are also employed to study many spectral lines simultaneously. Unfor-

SOURCE: J.-H. Jeong, J.-E. Lee, S. Lee, et al., 2025, “ALMA Spectral Survey of an Eruptive Young Star, V883 Ori (ASSAY). II. Freshly Sublimated Complex Organic Molecules in the Keplerian Disk,” The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 276(2):49, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/ad9450. CC BY 4.0.

tunately, intrinsically weak emissions can be easily overwhelmed by co-channel RFI, and even RFI at neighboring frequencies can drive receivers into saturation, affecting sensitivity and calibration across their entire band of observation.

The advent of routine observations over broad bandwidths by radio telescopes requires even more vigilance in RFI mitigation to enable further advances in radio astronomy. In particular, while improved RFI mitigation and excision techniques have expanded the scientific return of many facilities, they are an inferior option compared with a clean, interference-free spectrum. Indeed, RFI mitigation and excision adds additional costs, whether in receiver design, increased data storage due to more frequent time sampling, or increased computational resources required to process the high volume of recorded data.

All users, both passive and active, benefit from a clean spectrum. While radio astronomy facilities rely in part on geographic shielding and local designations of radio quiet zones7 or radio coordination zones to enable the broad band observations upon which continued scientific progress depends, it needs to be the shared goal of all users to assure effective use of the radio spectrum and to enable active and passive services to coexist.

HOW TO READ THIS REPORT

The remainer of this report is broken into three pieces. Chapter 2 provides the committee’s views on WRC-27 agenda items beginning with a brief overview. Chapter 3 then offers the committee’s perspective on selected preliminary agenda items for WRC-31. Finally, Chapter 4 concludes the report with some overarching remarks and observations on the importance of radio astronomy and Earth remote sensing and how these agenda items may affect scientific use of the radio spectrum.

The committee’s discussions of the agenda items in Chapters 2 and 3 follow a common format in most cases. First, the agenda item is quoted in full, and the ITU-R resolution that underpins it is summarized. The committee then describes the regulatory status of the band(s) under consideration in the agenda item, as well as the

___________________

7 Radio quiet zones are defined in Report ITU-R RA.2259-1 as “any recognized geographic area within which the usual spectrum management procedures are modified for the specific purpose of reducing or avoiding interference to radio telescopes, thereby maintaining the required standards for quality and availability of observational data.”

bands that are adjacent, with a particular focus on any allocations to, or protections afforded to, scientific use of the spectrum for RAS, EESS (passive), or EESS (active). This is followed by an outline of the specific science enabled by observations made in the bands discussed. The discussion of each agenda item ends with a list of recommendations to be considered by those participating in WRC-27 studies, negotiations, and subsequent regulatory change activities.

In order to make the discussion of each agenda item as independent as possible for the focused reader, the report generally redefines key acronyms in each discussion. Similarly, in many cases where two agenda items consider the same or nearby bands, there is some deliberate duplication of the descriptions of the scientific uses of the EESS or RAS measurements in each discussion.

Regulations Cited in Report

Regulatory documents referred to throughout this report are listed in Appendix D.

Figures Accompanying Many Agenda Item Discussions

In many cases, the discussion is accompanied by a figure illustrating the bands under consideration in the agenda item, along with bands in the same region allocated to (and/or identified for) RAS, EESS (passive) or EESS (active), and any bands afforded “all emissions prohibited” protection under RR 5.340. Figure 1-3 gives an example of two such figures. In addition, Chapters 2 and 3 begin with similar but more simplistic overview figures that summarize all the agenda items for WRC-27 (Chapter 2, Figure 2-1) and the preliminary agenda items for WRC-31 (Chapter 3, Figure 3-1).

Recommendations and Findings Associated with Agenda Items

In keeping with National Academies’ practices, recommendations are intended to be directed toward specific organizations or teams that are able to act on those recommendations. Most recommendations in this report are directed toward the teams leading and contributing to specific studies undertaken as part of work on WRC-27 agenda items and WRC-31 preliminary agenda items and/or those considering changes to the radio regulations in response to those studies. In some cases, recommendations are directed toward administrations (as noted above, “administrations” is the ITU par-

SOURCE: Data from International Telecommunication Union, “Radio Regulations,” http://handle.itu.int/11.1002/pub/8229633e-en, accessed February 10, 2025.

lance for national governments and the regulatory agencies therein). Other outcomes from the committee’s deliberations that are noteworthy but are not intended to be actionable by any particular team or entity are classified as findings.

Conventions for Specifying Frequencies

In general, this report follows the established ITU convention of expressing frequencies in kilohertz for values up to, but not including, 10,000 kHz, and in megahertz for values from 10 MHz up to, but not including, 10,000 MHz, with gigahertz used thereafter. Consistent with the ITU, the report omits the thousands separator (conventionally a comma in the United States), a choice it makes to avoid ambiguity between different international conventions (comma versus period). However, in a departure from the ITU approach, the committee has opted to simply omit the separator rather than replace it with a white space, as is the ITU practice, as the latter can be confusing to those unfamiliar with that convention, particularly when frequency ranges are quoted. An exception to this last point is when the report is directly quoting the agenda items themselves, as in the first part of each discussion, and as in Tables 1-1 and 1-2. Using an illustrative example to summarize, the frequency that many would write as 2.345 GHz the report will refer to as 2345 MHz, while the ITU would use 2 345 MHz.