Regulatory Processes for Rare Disease Drugs in the United States and European Union: Flexibilities and Collaborative Opportunities (2024)

Chapter: 4 Alternative and Confirmatory Data

4

Alternative and Confirmatory Data

Conclusion 4-1: The low prevalence of rare diseases and conditions, incomplete understanding of their underlying biology, ethical challenges in giving placebo to patients with rare diseases in double-blind clinical trials, and limitations in the ability to conduct randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for new therapies for them, have necessitated the collection and use of data from sources other than traditional RCTs for marketing authorization applications for rare disease drug products.

In keeping with this reality, the statement of task asked the committee to examine “the consideration and use of supplemental data submitted during review processes in the United States and the European Union, including data associated with open label extension studies and expanded access programs specific to rare diseases or conditions.” As described in Chapter 1, given the variety in types and uses of “supplemental” data in marketing authorization submissions, for the purposes of this report, the committee understands “supplemental” data to mean data that are generally collected outside the setting of a traditional randomized controlled clinical trial and used as alternative or confirmatory evidence in support of regulatory submission and review of a drug product.

This chapter is organized based on the following topics: guidance on alternative and confirmatory data (ACD), sources of ACD, trends in regulatory use, novel approaches for study design and data analysis drug review and approval, orphan medicine designation, expedited regulatory programs, biomarkers, and opportunities to enhance innovation. Over time, as new

technologies, study designs, and methods for data analysis emerge, additional sources of ACD may be applicable for use in marketing authorization applications for drugs to treat rare diseases and conditions.

GUIDANCE ON ALTERNATIVE AND CONFIRMATORY DATA

As described in Chapter 2, the statutory requirements for drug review and approval for rare diseases and conditions are the same as for non-rare diseases or conditions. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has discretion to accept one adequate and well-controlled clinical investigation in conjunction with alternative and confirmatory data, if FDA determines that, based on relevant science, such data would be sufficient to establish effectiveness.

The Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (Public Law 105–115) made clear that the substantial evidence requirement for effectiveness can be met by a single trial plus confirmatory evidence. A series of FDA guidances for industry1 elaborates on this thinking, by discussing approaches that can yield evidence that meets the statutory standard for substantial evidence of effectiveness, many of which can be leveraged by rare disease development programs (FDA, 2019b). Examples of types of confirmatory evidence that could be used to supplement one clinical investigation, some of which may be generated during conventional drug development programs, are described in Table 4-1. FDA has used these data sources to make regulatory decisions (see Figure 4-1).

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA’s) guidelines on the use of one pivotal trial state that the “fundamental requirement” of Phase 3 studies is that they consist of “adequate and well-controlled data of good quality from a sufficient number of patients, with a sufficient variety of symptoms and disease conditions, collected by a sufficient number of investigators, demonstrating a positive benefit/risk in the intended population at the intended dose and manner of use” (EMA, 2001). The extent of data needed will depend on what is already known about the product and related products; the minimum requirement is generally one study with statistically compelling and clinically relevant results. In applications that rely on only one pivotal study, EMA notes that the study in question will be examined closely for internal validity, external validity, clinical relevance, statistical significance, data quality, internal consistency, center effects, and

___________________

1 Providing Clinical Evidence of Effectiveness for Human Drug and Biological Products—FINAL Guidance (FDA, 1998). Demonstrating Substantial Evidence of Effectiveness for Human Drug and Biological Products—DRAFT Guidance (FDA, 2019b). Demonstrating Substantial Evidence of Effectiveness with One Adequate and Well-Controlled Clinical Investigation and Confirmatory Evidence—DRAFT Guidance (FDA, 2023d).

TABLE 4-1 Examples of Types of Confirmatory Evidence from FDA Guidance

| Evidence Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Clinical evidence from a related indication | Data from clinical investigation that was used to support a previous approval or data from an adequate and well-controlled study that demonstrated the effectiveness of the drug for a related, unapproved indication |

| Mechanistic or pharmacodynamic evidence | Data that provide strong mechanistic support (e.g., pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data collected via clinical and/or animal studies) for a treatment effect on a particular disease |

| Evidence from a relevant animal model | Data (e.g., proof-of-concept, pharmacological, toxicology data) from an established animal model of disease |

| Evidence from other members of the same pharmacological class | Data from adequate and well-controlled trials of other drugs in the same pharmacological class that have been approved for the same indication |

| Natural history evidence | Data that can provide confirmatory evidence to support a single adequate and well-controlled clinical trial |

| Real-world data/evidence | Data related to patient health status or delivery of care that are routinely collected (e.g., electronic health records, medical claims data, registries) and clinical evidence about the use and potential benefits and risks of a drug treatment based on real-world data |

| Evidence from expanded access use of an investigational drug | Data collected through expanded access that are of sufficient quantity and quality to be considered for use as confirmatory evidence. |

NOTE: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

SOURCE: FDA, 2023d.

the plausibility of the tested hypotheses (EMA, 2001). EMA also provides guidance on the use of ACD and alternative trial designs as well as on such topics as trials in small populations, real-world evidence, registry-based studies, and single-arm trials (see Table 4-2).

While FDA and EMA have identified some specific types and sources of ACD, as described above, these may change over time as new technologies and methods for data analysis emerge. FDA notes that the list provided in the 2023 guidance is not exhaustive, and each application is considered on a “case-by-case” basis (FDA, 2023d). While this approach could imply that there is no standard approach for considering the use of ACD, examples do provide a helpful basis for how the agency will consider the use of ACD for future marketing authorization applications. Additional context and precedent would give sponsors and patient groups more clarity on how ACD can be incorporated into drug development programs.

TABLE 4-2 EMA Resources on Trial Design, Statistical Methods, and Alternative and Confirmatory Data

| Guideline | Source |

|---|---|

| Complex Clinical Trials—Questions and Answers | EMA (2022a) |

| Final Concept Paper—E20: Adaptive Clinical Trials | ICH (2019) |

| Concept Paper on Platform Trials | EMA (2022b) |

| Design Concept for a Confirmatory Basket Trial | Beckman (2018) |

| ICH Guideline E17 on General Principles for Planning and Design of Multi-Regional Clinical Trials | EMA (2017) |

| Points To Consider On Application With 1. Meta-Analyses; 2. One Pivotal Study | EMA (2001) |

| Guideline on Clinical Trials in Small Populations | EMA (2006) |

| E10—Choice of Control Group in Clinical Trials (see sections 1.3 and 2.5 for information on external and historical controls) | ICH (2001) |

| Guideline on Registry-Based Studies | EMA (2021a) |

| A Vision for Use of Real-World Evidence in EU Medicines Regulation | EMA (2021b) |

| Good Practice Guide for the Use of the Metadata Catalogue of Real-World Data Sources | EMA (2022c) |

| Real-World Evidence Framework to Support EU Regulatory Decision-Making | EMA (2023b) |

| Marketing Authorization Applications Made to the European Medicines Agency in 2018–2019: What was the Contribution of Real-World Evidence? | Flynn et al. (2022) |

NOTE: EMA = European Medicines Agency.

SOURCES OF ALTERNATIVE AND CONFIRMATORY DATA

Natural History Studies

A natural history study is a preplanned observational study that is designed to capture information about the course of a disease. Information is collected about symptoms and outcomes, as well as about demographic, environmental, genetic, and other variables that may affect the patient’s experience with the disease and be associated with the natural history of the disease (FDA, 2023b). Depending on the disease and the availability of treatment, a natural history study may include patients who are untreated, patients receiving the standard of care, or patients receiving an emergent treatment (FDA, 2019c). An example of a common mechanism for acquiring data for natural history studies is a patient or disease registry.

FDA published draft guidance in 2019 on Rare Diseases: Natural History Studies for Drug Development which states, “Information obtained from a natural history study can play an important role at every stage of

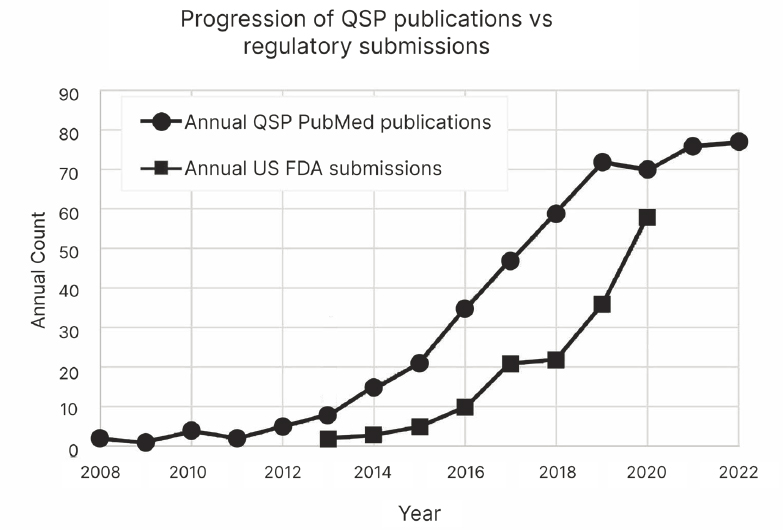

NOTES: ACD = alternative and confirmatory data; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

drug development, from drug discovery to the design of clinical studies intended to support marketing approval of a drug and beyond into the postmarketing period” (FDA, 2019c). FDA also notes that natural history studies may have benefits for patients living with rare diseases that go beyond drug development and approval. Natural history studies can establish communication pathways, identify disease-specific centers of excellence, build knowledge about the current standard of care and potential improvements to care, and provide estimates of the prevalence of the disease (FDA, 2019c).

EMA published a guideline in 2021 on the use of registry-based studies to support regulatory decision-making (EMA, 2021a). In the guideline, EMA clarified the differences between a registry-based study and a patient registry: namely, that a registry is an organized system that collects uniform data, and that a registry-based study is an investigation of a research question that uses the infrastructure of such a registry. EMA identified several uses for registries and registry-based studies, including to complement the evidence submitted for marketing authorization. Patient registries can serve as a source of information on standards of care, incidence, prevalence, determinants of disease, and characteristics of the population. In addition, registries can be used for such purposes as recruitment, sample size calculation, and endpoint identification. Patient registries may be particularly valuable for rare disease communities as they serve as a resource to help inform disease characterization and the development and validation of biomarkers and clinical endpoints and, in some cases, may supplement, confirm, or replace information gathered through a traditional randomized clinical trial. EMA emphasized in its guideline that it is recommended that sponsors obtain advice from EMA early on regarding the acceptability of a registry-based study.

Examples

There are several examples that illustrate how natural history studies and patient registries can supplement and augment marketing authorization submissions for drugs to treat rare diseases and conditions. (For further details and references regarding these examples, see Appendix H.) In 2023, after considering confirmatory evidence including natural history data, FDA approved SkyClarys (omaveloxolone) for the treatment of Friedreich’s ataxia, a rare, inherited, neurodegenerative disease that typically affects children and teens and gradually worsens over time (see Box 4-1). On the same basis, EMA recommended market approval later in the same year.

Additionally, FDA (in May 2019) and EMA (in March 2020) both approved Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi) for spinal muscular atrophy based on a natural history control in comparison to a treatment

BOX 4-1

Use Case: SkyClarys (Friedreich’s Ataxia)

On February 28, 2023—Rare Disease Day— the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced approval of SkyClarys (omaveloxolone), the first approved treatment for Friedreich’s ataxia (FA), a rare, inherited, neurodegenerative disease that typically affects the nervous system and heart in children, teens, and adults and worsens over time. The sponsor submitted data supplemental to its New Drug Application, including the use of an external control—a cohort of natural history participants who were closely propensity-score matched to the participants in the open-label extension of the single study. Natural history data played a key role in informing regulatory decision-making as FDA’s SkyClarys review summary concludes:

Given the serious and life-threatening nature of FA and the substantial unmet need with no approved treatments, some level of uncertainty is acceptable in this instance and consideration of these results in the context of regulatory flexibility is appropriate. The single adequate and well-controlled study with positive results on a clinically meaningful primary outcome, accompanied by confirmatory evidence from the natural history comparison, in addition to the pharmacodynamic data supporting the biologic plausibility of the treatment effect, are adequate to provide substantial evidence of effectiveness. There are no safety issues that would preclude approval. Additional pharmacovigilance and adequate monitoring for risks of liver injury and cardiac events are warranted in the postmarketing setting. (FDA, 2023h)

Based on the same single-trial results and supplemental data, in December 2023, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) followed with a recommendation for market approval of SkyClarys, and the European Commission approval followed in February 2024. EMA’s review summary regarding the confirmatory evidence concludes:

“This exploratory analysis should be interpreted cautiously given the limitations of data collected outside of a controlled study, which may be subject to confounding” (EMA, 2024d).

This use case demonstrates how Alternative and Confirmatory Data can be used in support of regulatory submission of rare disease drug products provided that (1) it can address regulatory concerns of possible uncertainties, (2) it can provide adequate substantial evidence of effectiveness, and (3) there is no safety issue that would preclude approval.

groups. The increase in survival between treatment groups and the natural history control provided evidence of the treatment’s effectiveness. Zolgensma is a directly administered adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector that delivers the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN) gene for the treatment of pediatric patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) who have bi-allelic mutations in the SMN gene. The primary evidence of effectiveness for regulatory approval was based on a single, ongoing, Phase 3, open label, single-arm study of children with infantile onset SMA; natural history data were used as the control, and a completed Phase 1 study provided support of evidence. The primary endpoints in the Phase 3 trial were “alive without permanent ventilation” and “sitting without support.” Based on the strong natural history of the disease, no patients meeting the study entry criteria would be expected to attain the ability to sit without support, and only about a quarter of patients would be expected to remain alive without permanent ventilation beyond 14 months of age. Due to this strong knowledge of the natural history and the very significant treatment effect, the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) approved Zolgensma during the ongoing Phase 3 trial and with the natural history control rather than a concurrent control arm (Anatol, 2024).

Programs to Support Natural History and Patient Registries

There are a number of public and private initiatives that are designed to support the development of patient registries and the conduct of natural history studies. A 2016 cooperative agreement between FDA and the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) launched a program that supported 20 rare disease patient groups in the development of natural history studies (NORD, 2016). The groups that were chosen represented diseases with diagnostic challenges, limited or no research, and a broad range of symptoms and systems. Another NORD initiative is called IAMRARE. This registry programs allows patient advocacy groups to build patient registries and collect natural history data (NORD, n.d.). As of 2023, the IAMRARE program has over 50 natural history studies with over 18,000 patients and covers more than 75 rare diseases (NORD, 2023). Similarly, Global Genes, another nonprofit patient advocacy organization, hosts standardized patient-entered natural history data on its RARE-X platform for rare disorders, including 7,700 participants from 90 countries. Many other natural history registries and platforms exist (nonprofit and for-profit) that are designed specifically to collect patient-entered longitudinal natural history data from rare disease groups, such as Simons Searchlight, Across Healthcare’s Matrix, Sanford CoRDs, and JEEVA, as well as academic efforts and clinical centers around the country. These natural history projects may or may not be collecting information that is useful or sufficient for submission

as natural history controls for drug approvals; thus, pharmaceutical firms often conduct proprietary observational and natural history studies on rare diseases prior to submitting new drug applications.

FDA has supported natural history studies since 2016 for patients with rare diseases. FDA’s Office of Orphan Products Development (OOPD) provides sponsors and other entities grants to conduct clinical trials and natural history studies on rare diseases. There are typically 60 to 85 ongoing grant projects every year. OOPD awards approximately five to twelve new grants each year. FDA natural history program funds well-designed, protocol-driven natural history studies that address knowledge gaps, support clinical trials, and advance rare disease medical products. As of the time of writing this report, OOPD has supported more than 15 natural history studies (FDA, 2023b) (see Box 4-2). An FDA study on the clinical trial grant program found that of the 85 grants issued between 2007 and 2011, 9 product approvals were partially supported by grant funding (Miller et al., 2020).

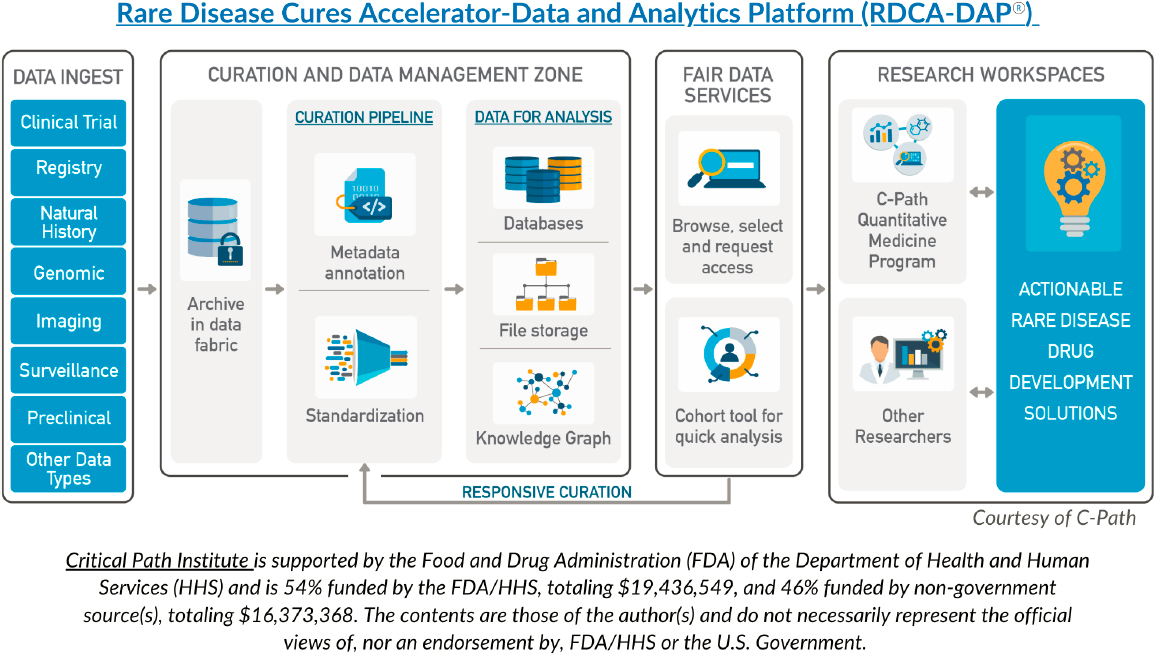

The Rare Disease Cures Accelerator-Data and Analytics Platform (RDCA-DAP®), which is funded by FDA and operated by the Critical Path

BOX 4-2

Diseases Studied by Ongoing and Past FDA Office of Orphan Products Development Natural History Grants from 2016 to 2023

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Angelman syndrome

- Ataxia–telangiectasia

- Autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

- Castleman disease

- Chronic kidney disease

- Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- Friedreich’s ataxia

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Medullary thyroid carcinoma

- Myotonic dystrophy Type 1

- Ornithine‐δ‐aminotransferase

- Osteoporosis

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Sarcoidosis

__________________

SOURCE: FDA, 2023b.

Institute in collaboration with NORD, is a centralized database and analytics hub that contains standardized data on a growing number of rare diseases and that allows secure sharing of data collected across multiple sources, including natural history studies/patient registries, control arms of clinical trials, longitudinal observational studies, and real-world data (Critical Path Institute, n.d.). Since RDCA-DAP® was launched in 2021, the platform has enabled access to data from over 30 rare disease areas with more data being added over time (see Box 4-3). Drug developers and other data users can access the platform to better understand disease progression and heterogeneity, to more effectively target therapeutics, and to inform trial design and other aspects of rare disease drug development. The establishment of regulatory-grade fit-for-purpose natural history platforms has the potential to support marketing authorization submissions for drugs to treat rare disease and conditions. RDCA-DAP® offers a trusted and reliable

BOX 4-3

Diseases Covered by Critical Path Institute’s Rare Disease Cures Accelerator–Data and Analytics Platform

- Angelman syndrome

- Congenital hyperinsulinism

- Desmoid tumor

- Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD)

- Friedreich’s ataxia

- GNE myopathy

- hnRNP related disorders

- Kidney transplant

- K1F1A associated neurological disorder

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome

- Mitochondrial disease

- Nectrotizing enterocolitis

- Niemann-Pick disease

- Pemphigus & pemphigoid

- Phenylketonuria (PKU)

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Prader-Willi syndrome*

- Progressive supranuclear palsy*

- Rare epilepsies*

- RYR-1 gene mutation*

- Spinal muscle atrophy with respiratory distress*

- Spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2, 3 & 6

- Sturge-Weber syndrome

- Tuberous sclerosis

__________________

NOTE: * Indicates disease with datasets that are currently discoverable on the platform.

SOURCE: Critical Path Institute, n.d.

source of standardized ACD that can be used for clinical trial design and effective external controls.2

The RDCA-DAP® process (see Figure 4-2) involves aggregating and aligning patient-level data from a variety of trials, observational studies, patient registries, and electronic health records. The Critical Path Institute works with stakeholders to standardize data collection and to curate and standardize data entered into the platform. A number of rare disease consortiums both contribute and use data from the platform; the contribution and use of these data are negotiated between the contributing organization and Critical Path Institute. These data are curated and standardized into databases; researchers can request access for quick analysis. The platform is compliant with European Privacy Regulations (Critical Path Institute, n.d.). On a smaller scale, a data aggregator program called “Linking Angelman and Dup15q Data for Expanded Research” (LADDER) is a database platform that links data on individuals with Angelman or Dup15q syndromes collected from multiple sources, such as research studies, registries, caregiver reports, and clinic visits (Angelman Syndrome Foundation, n.d.).

One goal of RDCA-DAP® is to shorten the timeline for the development of treatments for rare diseases. Prior to LADDER and RDCA-DAP®, existing data on rare diseases tended to be siloed, and data that were available may not have been standardized, digitized, or interoperable (Barrett et al., 2023). Giving researchers and drug developers access to standardized, usable data can lead to new insights about the disease and to improved processes for clinical trials (NORD, 2021). For example, using existing data to develop models of disease can guide the design of clinical trials, potentially making research faster and more cost-effective (NORD, 2021). RDCA-DAP® is designed to make each step of drug development more efficient, including pre-clinical research, clinical research, FDA review, and post-market safety monitoring (NORD, 2021).

Most programs listed above are early on in development, so the committee was unable to assess their impacts on regulatory decision-making. However, the notable success of the approval of SkyClarys for the treatment of Friedreich’s ataxia has demonstrated how such tools as RDCA-DAP® can facilitate research and development for rare diseases and conditions (Barrett et al., 2023). Despite the opportunities for using natural history data in regulatory decision-making and efforts on the part of government and nonprofit funders to establish and support natural history registries, most patients living with rare diseases and conditions do not have access to this type of resource.

___________________

2 This sentence was edited after release of the prepublication version of the report to correctly specify the type of ACD.

Conclusion 4-2: Understanding the natural history of a disease—as well as the factors that affect its progression and outcomes—is important for drug development. However, for most rare diseases and conditions, there is often little information about natural history.

RECOMMENDATION 4-1: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should enable the collection and curation of regulatory-grade natural history data to enhance the quality and accessibility of data for all rare diseases. This should include, but not be limited to:

- Continuation and expansion of support for current rare disease natural history design and data collection programs, such as FDA’s Office of Orphan Products Development awarding clinical trial and natural history study grants.

- Continuation and expansion of data aggregation, standardization, and analysis programs, including, but not limited to, Critical Path Institute’s Rare Disease Cures Accelerator-Data and Analytics Platform.

- Support, education, training, and access to resources/infrastructure for nascent rare disease advocacy groups to enable the standardization and integration of patient-level data for future regulatory use.

- Continuation and expansion of collaboration with other agencies (e.g., National Institutes of Health Rare Disease Clinical Research Network) to expand natural history design and data collection resources for all rare diseases.

- Periodic assessment regarding the impact and opportunities for improvement of ongoing programs for the collection, curation, and use of natural history data in regulatory decision-making for rare disease drug development programs.

Expanded Access/Compassionate Use

In the United States, expanded access or “compassionate use” allows critically ill patients with a serious or life-threatening disease or condition to receive investigational drugs—products that have not yet been approved for marketing by FDA. In the United States, expanded access may be appropriate when all the following apply:

- “Patient has a serious or immediately life-threatening disease or condition.

- “There is no comparable or satisfactory alternative therapy to diagnose, monitor, or treat the disease or condition.

- “Patient enrollment in a clinical trial is not possible.

- “Potential patient benefit justifies the potential risks of treatment.

- “Providing the investigational medical product will not interfere with investigational trials that could support a medical product’s development or marketing approval for the treatment indication” (FDA, 2024b).

Similarly, in the European Union, compassionate use programs can be considered if patients have a “life-threatening, long-lasting, or seriously debilitating illness, which cannot be treated satisfactorily with any currently authorized medicine” (EMA, n.d.). In the case of EMA, the medicine must be in clinical trials or have a submitted marketing authorization application.

Expanded access programs are not designed to collect data for research purposes. However, data collected through these programs could be a source of alternative or confirmatory data that could help supplement clinical trial data in the regulatory review process (Wasser and Greenblatt, 2023). While real-world clinical data about the expanded access use of investigational drugs are not as rigorous or standardized as typical clinical trial data, they may provide insights on safety in real-world settings.

Each year, FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) receives over 1,000 requests for expanded access to investigational drugs (Jarow and Moscicki, 2017). A review of expanded access requests over a 10-year period between 2005 and 2014 showed that the number of requests increased over time and that most nonemergency submissions were for anti-infective and oncology products (Jarow et al., 2016). There is the potential for expanded access to help treat rare disease patients and advance drug development. While it is the case that investigational drug products may not be effective and could cause serious side effects, for rare disease patients with unmet medical needs, expanded access may be their only opportunity to receive treatment.

Regulatory Guidance

There is a tension between the primary and original purposes of expanded access—to provide treatment to patients with unmet needs—and the potential for collecting evidence on the safety and effectiveness of these treatments (Polak et al., 2022). While FDA and EMA have both used data from expanded access as part of a regulatory decision (see examples below), neither agency has been explicit about whether and to what extent expanded access data should be collected or used. EMA’s 2007 guideline on expanded access states, “Although safety data may be collected during compassionate use programmes, such programmes cannot replace clinical trials for investigational purposes. Compassionate use is not a substitute for properly conducted trials” (EMA, 2007). FDA’s guidance on compassionate use distinguishes between expanded access and the use of an investigational

drug in a clinical trial by stating that “expanded access uses are not primarily intended to obtain information about the safety or effectiveness of a drug” (FDA, 2022a). Furthermore, FDA expresses concern that expanded access for rare disease treatment has the potential to interfere with clinical trials because the number of potential trial participants is limited; clinical trials should be initiated before expanded access is offered, and expanded access should only be available for patients who are ineligible or unable to participate in a trial (FDA, 2022a).

Despite the use of expanded access data in regulatory submissions, there is no consensus among regulators, bioethicists, or drug developers on the role that these data should play in drug development (Bunnik and Aarts, 2021; Bunnik et al., 2018; Kearns et al., 2021; Polak et al., 2022; Polak et al., 2020; Rozenberg and Greenbaum, 2020; Sarp et al., 2022).

Examples

There are some examples of new drug applications that have included expanded access data, such as:

- “vestronidase to treat mucopolysaccharidosis VII, a rare genetic enzyme deficiency;

- “lutetium 177 dotatate injection, a radiolabeled drug for rare gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors;

- “cannabidiol, an adjunctive treatment for seizures associated with two rare conditions;

- “combined sodium phenylacetate and sodium benzoate to treat acute hyperammonaemia in patients with a rare urea cycle disorder; and

- “nitisinone to treat hereditary tyrosinaemia type 1” (Wasser and Greenblatt, 2023).

However, streamlining the use of expanded use data in marketing authorization submissions, would likely require that data collection be standardized and align with the regulatory review process.

As of 2018, FDA and EMA had collectively approved 49 drug-indication pairs based in whole or in part on data from expanded access; of these, 63 percent were designated as orphan medicines (Polak et al., 2022). The treatment for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors was approved based on a small randomized controlled trial (RCT) that was supplemented with data from 558 patients treated under expanded access (Polak et al., 2022). In another case, a treatment was approved by both FDA and EMA based solely on expanded access data; a treatment for rare disorders in bile acid metabolism was approved based on data from two expanded access programs with a total of 85 patients (Polak et al., 2022).

Open-Label Extension Studies

After the completion of Phase 3 of a clinical trial, participants may be offered the opportunity to enroll in an extension study. Unlike a controlled, blinded trial, all participants in an open-label extension study are given the investigational drug with no blinding. The objective of open-label extension studies is generally to gather information about safety and tolerability in the long-term use of the product, which can be useful in the marketing application (Taylor and Wainwright, 2005). In some cases, open-label extension studies can provide longer-term efficacy data as well (Wang et al., 2022).

Relevance to Rare Disease

Patients with rare diseases may be hesitant to participate in a trial with a placebo arm, particularly if there is no existing treatment or the disease is severe or rapidly progressing (Brown and Ekangaki, 2023). In addition, there may be ethical concerns related to giving only some patients the intervention when there is no alternative treatment. Adding an extension study can make participation in a RCT more appealing because all participants will eventually have a chance to take the investigational drug. In a survey of patients with progressive ataxias, a placebo arm in a trial was seen as a disincentive to participation, and many patients reported that they would be more likely to participate in a trial if an open-label extension study was offered (Thomas-Black et al., 2022). Among other examples, open-label extension data were used in the authorization of Relyvrio for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (see Box 4-4).

Regulatory Guidance

FDA does not have guidance specifically on open-label extension studies, but these studies are mentioned in a number of other guidance documents. For example, in the Agency’s guidance Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations (FDA, 2020b), FDA suggests three approaches for addressing the challenges in recruiting and enrolling participants in clinical trials for rare diseases; one of these is “Make available an open-label extension study with broader inclusion criteria after early-phase studies to encourage participation by ensuring that all study participants, including those who received placebo, will ultimately have access to the investigational treatment” (FDA, 2020b). Additionally, a poster from the 2023 FDA Science Forum provides recommendations on conducting an open-label trial when fully blinding the trial is not possible (Higgens and Levin, n.d.).

BOX 4-4

Use Case: Relyvrio (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis)

Relyvrio (sodium phenylbutyrate and taurursodiol) for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)—known as Albrioza in Europe—was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in September 2022 (FDA, 2022c) and received a negative opinion from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in December of 2023 (EMA, 2024a). At the time of approval and opinion, there were only two available treatments in the United States (FDA, 2022c) and one available treatment in Europe (EMA, 2023a). Both FDA and EMA reviewed the same clinical study along with open label extension data (EMA, 2023a; FDA, 2022c). FDA granted Relyvrio approval because the serious nature of the disease along with the unmet medical need warranted the use of regulatory flexibility. As a result, FDA determined the benefits outweighed the risk (FDA, 2022c). In contrast, EMA provided a negative opinion because the data was found to be “neither robust nor statistically compelling” (EMA, 2023a). In 2024, Relyvrio failed the confirmatory clinical trial with no evidence of clinical benefit in the primary or any of the secondary or exploratory endpoints. The company has withdrawn the drug from the U.S. market (Amylyx Pharmaceuticals, 2024).

__________________

NOTE: See Appendix H for more information on Relyvrio.

External Control Groups (Concurrent and Historical)

FDA regulatory standards for substantial evidence of effectiveness from adequate and well-controlled trials typically include the use of a control group that is randomized and evaluated at the same time as the intervention group. However, a concurrent internal control group may not always be feasible or ethical when studying rare diseases, so an external control group may be constructed as a comparator (Jahanshahi et al., 2021). An external control group can be based on data collected at an earlier time (i.e., historical control) or on data that is being collected at the same time as the clinical trial, but in another setting (i.e., concurrent control). For example, if a trial on an investigative drug has already been conducted and included a randomized control group, the data from this group could be compared to new data from a trial with no control group. An external control group must closely resemble the intervention group to ensure an apples-to-apples comparison. One approach for establishing a close match is the use of a statistical method called propensity score matching, which matches the characteristics of individuals in the external control group to group participants’ characteristics in the intervention group (Jahanshahi et al., 2021).

Relevance to Rare Disease

For many drug trials for rare diseases and conditions, an internal control may not be feasible or ethical to use due to limited numbers of patients or the unmet medical need of patients or both. Single-arm or non-randomized trials, in which all participants receive the experimental therapy, are often used in rare disease drug development, generally for serious or life-threatening disorders for which there is a poor prognosis, standard of care therapies are inadequate, and there is promising evidence of the therapeutic candidate’s potential benefit (e.g., pharmacologic data). In these circumstances, an external control group may be used; data from the intervention group is compared with data from an external group that received a placebo (or standard-of-care) in order to determine the true effect of the intervention (Burcu et al., 2020; Jahanshahi et al., 2021).

Regulatory Guidance

In 2023 FDA published the draft guidance Considerations for the Design and Conduct of Externally Controlled Trials for Drug and Biological Products (FDA, 2023c). This guidance provides recommendations to sponsors and investigators on the design and analysis of trials that use external control data; the guidance acknowledges that external controls may come from many sources of data but focuses specifically on patient-level data from other clinical trials or real-world data sources, including from electronic health records or medical claims.3 In addition, FDA’s 2023 guidance Rare Diseases: Considerations for the Development of Drugs and Biological Products contains a section on the use of external controls in rare disease trials (FDA, 2023f). FDA notes the limitations of external controls, including the lack of blinding and inability to eliminate systematic differences between groups, and states that trial designs that use an external control group should be “reserved for specific circumstances, such as clinical investigations where the drug effect can be demonstrated in diseases with well-understood and -characterized natural history, high and predictable mortality or progressive and predictable morbidity, and clinical investigations in which the drug effect is large and self-evident” (FDA, 2023f). FDA recommends that sponsors engage in early discussion with the relevant review division if considering such a design.

In 2023, EMA published a reflection paper on establishing efficacy based on single arm trials, which acknowledged that in exceptional cases, external controls could serve as a direct comparison, but also noted that it was beyond the scope of the paper. EMA stated, “While methods that

___________________

3 This sentence was updated after release of the prepublication version of the report to specify use of data from external controls.

directly incorporate external data into the analysis come with a promise to provide useful insights and potentially reduce bias, they add complexity to pre-specification and rely on additional assumptions that are often not transparent. Consequently, approaches that directly incorporate external data should be carefully evaluated on a case-by-case basis” (EMA, 2023c).

Examples

External controls have successfully been used in several new drug applications for rare disease products (Khachatryan et al., 2023). For example, Cerliponase alfa (Brineura) was approved by both FDA and EMA in 2017 for the treatment of a rare pediatric neurological disease; the approval was based on data from 23 patients in an open-label single arm trial, with a historical control group derived from a registry database (Khachatryan et al., 2023).

Extrapolation from Existing Studies

In some cases, the safety or efficacy of a drug product, or both, can be supported or demonstrated by extrapolating data from other studies. Extrapolation is often used when a drug was studied in a narrow group of trial participants; the positive results from the trial are extrapolated to a broader population of patients, and the drug is approved with the broader indication (Feldman et al., 2022). For example, a drug may be studied in adults 18–59 who have a mild or moderate version of the disease, but results are extrapolated to grant an indication that includes all adult patients with any level of severity. Extrapolation may also be used to approve a drug approved for adult use for use in the pediatric population if the course of the disease and the expected response to the drug are sufficiently similar between the adult and pediatric patient populations (ICH, 2022).

Relevance to Rare Disease

Some rare diseases may affect only a handful of patients but are closely related to other rare diseases and collectively these variations affect a significant number of patients. For example, cancers can be classified by both location and biomarker profile. In cancers where the location and biomarker profile are rare, there may be too few patients to conduct an RCT. In this case, data from a trial that tested an intervention for a cancer with a specific biomarker and a specific location may be extrapolated to approve an indication for a cancer with the same biomarker but a different location (Cho et al., 2022). Given that rare diseases often present in childhood, extrapolation may also be useful in applying data from adult to pediatric populations.

Regulatory Guidance

In 2022, EMA and FDA, along with other regulatory agencies, adopted the draft International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Harmonized Guideline: Pediatric Extrapolation (ICH, 2022). This guidance identifies factors to consider when using extrapolation for pediatric populations and notes that if extrapolation is used for approval, additional data may need to be collected post-approval. The guidance notes special safety considerations when the drug is a new molecular entity, when there are known age-related safety concerns, when there are safety findings that would be of particular importance in children, and when the drug has a narrow therapeutic index (ICH, 2022).

Examples

An analysis of 105 novel FDA approvals between 2015 and 2017 found that extrapolation was used in 23 approvals (Feldman et al., 2022). Extrapolation was most common for disease severity (n=14), followed by disease subtype (n=6) and concomitant medication use (n=3) (Feldman et al., 2022). The study did not note whether any of the approvals were for orphan medicines. In the area of rare disease, the 2017 approval of vemurafenib for a rare cancer called Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) is an example of the use of extrapolation for regulatory decision-making (Cho et al., 2022). Clinical trials with patients with BRAFV600 mutated metastatic melanoma had found that treatment with vemurafenib, a BRAF-inhibitor, led to improved survival. The BRAFV600 mutation is also present in ECD, for which there are only 800 reported cases in the literature. A “basket trial” of 208 patients in seven cohorts enrolled 22 patients with ECD with BRAF V600 mutation. Results from the group of 22 patients provided evidence that the treatment was associated with improved function and symptoms. The approval of vemurafenib for the treatment of ECD was based on this efficacy data, along with supportive safety data from 3,378 non-ECD patients who were treated with the same dose and schedule (Oneal et al., 2018).

Patient and Caregiver Reported Outcomes

A patient-reported outcome (PRO) is information that is reported directly by the patient, rather than information reported by a clinician or researcher. PROs may include information about symptoms, day-today functioning, and mental and emotional well-being (FDA, 2009). As discussed elsewhere in this report, many rare diseases have heterogenous

clinical manifestations. Different patients and their caregivers experience the same disease in different ways and may value different types of outcomes. Furthermore, health care professionals and researchers may place emphasis on certain outcomes that are less important to patients and caregivers, and vice versa. For example, a patient may care more about his or her day-to-day function, whereas a researcher is looking at overall survival rates. For these reasons, PROs are a particularly relevant measure in the assessment of products for rare disease. Using PROs to supplement other data on safety and efficacy can provide a fuller picture of whether the benefits of a treatment outweigh the risks and can be used to support marketing authorization applications (FDA, 2009).

Real-World Evidence Studies

Real-world data (RWD) and real-world evidence (RWE) are related but separate terms that are defined by both FDA and EMA. FDA defines RWD as “data relating to patient health status and/or the delivery of health care routinely collected from a variety of sources” (FDA, 2023g). EMA defines RWD as “routinely collected data relating to a patient’s health status or the delivery of health care from a variety of sources other than traditional clinical trials” (EMA, 2024c). RWD can come from many sources including electronic health records, claims and billing data, data from patient registries, patient-generated data, and data from wearable technologies (Liu et al., 2022). RWE is defined by FDA as “clinical evidence about the usage and potential benefits or risks of a medical product derived from an analysis of RWD” and by EMA as “information derived from an analysis of RWD” (Cave et al., 2019; FDA, 2023g). Hybrid and pragmatic trial designs, as well as observational studies, can generate RWE (Liu et al., 2022). Due to the lack of information on many rare diseases, and the challenges involved in conducting RCTs, RWD and RWE can serve as a rich source of information about disease progression, patient experiences, treatment effects, and relevant endpoints. In addition, RWD can be used as control data in trials where randomizing patients to a placebo or standard-of-care group may be infeasible or unethical (Liu et al., 2022).

TRENDS IN REGULATORY USE

While there is some evidence that the approval processes for the treatment of several rare diseases have leveraged different approaches to establish efficacy—e.g., single-arm trials, the use of external control data, surrogate endpoints and supplemental data—data on the phenomenon were generally lacking. A study comparing characteristics of orphan cancer drugs and their pivotal clinical trials versus non-orphan drugs, using publicly available data

from FDA, found that pivotal trials for recently approved orphan cancer drugs were more likely to have been smaller and to have used surrogate endpoints to assess efficacy (Kesselheim et al., 2011).

In Europe, a study assessing regulatory evidence supporting orphan medicinal product authorizations found uncertainties, including the use of intermediate variables without validation, highlighting opportunities for improvement (Pontes et al., 2018).

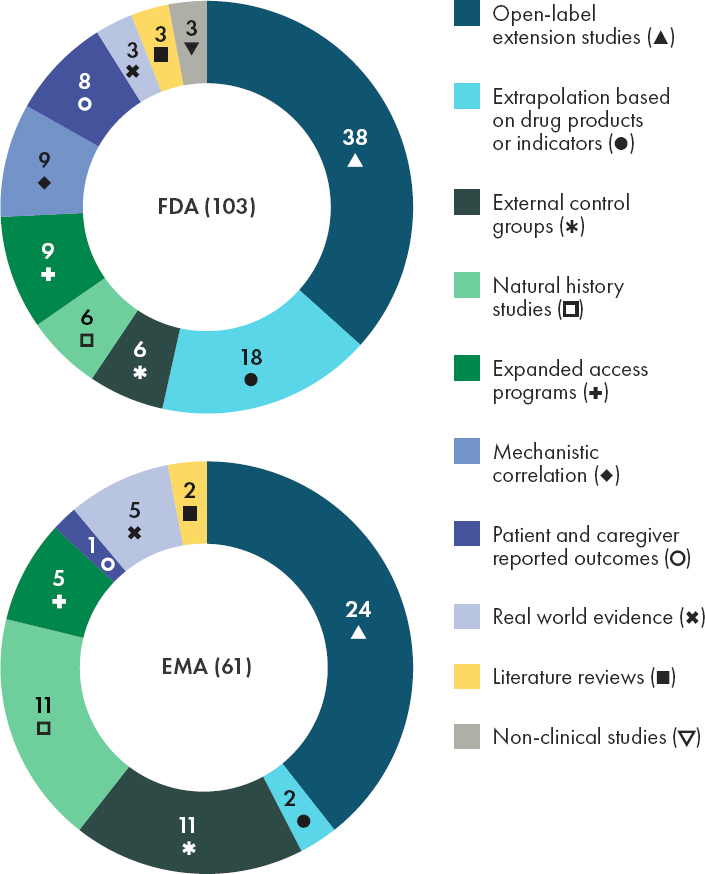

To better understand current trends in the regulatory use of ACD, the committee commissioned an analysis of EMA and FDA marketing authorization approvals for orphan drug products to examine trends in the use of these types of data for informing regulatory decision-making. ACD was defined as data deriving from natural history studies (e.g., patient registries), expanded access programs, open-label extension studies, external control arms (concurrent and historical), case reports, extrapolation based on data from related drug products or indications, mechanistic correlation (e.g., pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics), nonclinical studies (e.g., stability and quality control data), passive data collection, patient and caregiver reported outcomes (e.g., preference data), real-world evidence, and literature reviews. The committee only reviewed ACD that supported orphan product approval and were articulated in a public assessment report from the following year ranges: 2013–2014, 2017–2018, 2021–2022 (see Appendix D for full methodology).

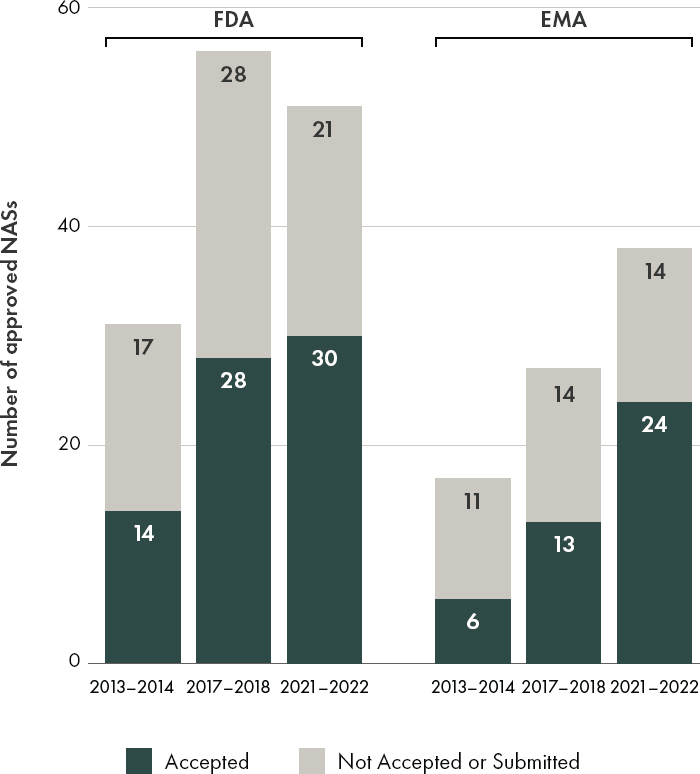

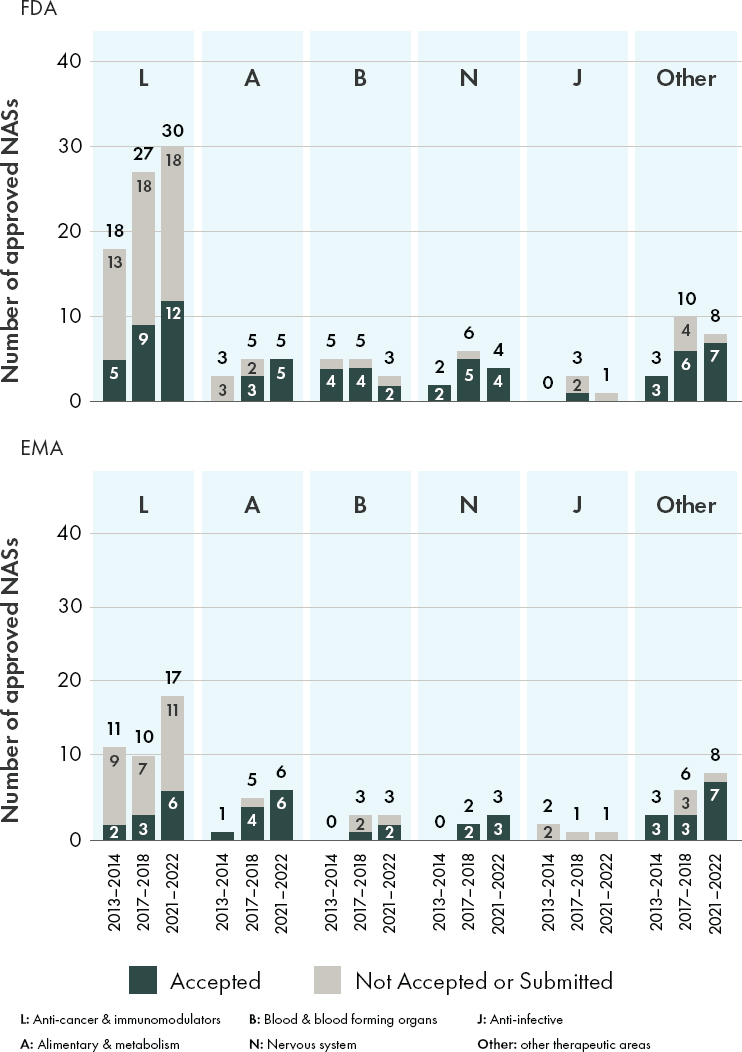

An examination of the types of accepted ACD referenced by FDA and EMA between 2013 and 2022, while limited in scope based on the selected keywords and fields, indicates that both agencies are willing consider a variety of alternative and confirmatory data sources in their regulatory decision-making for orphan drugs (see Figures 4-1 and 4-3). In 2021–2022, the proportion of orphan drug approvals that included the use of alternative and confirmatory data were similar between FDA (59 percent or 30/51 products) and EMA (63 percent or 24/38 products) (see Figure 4-3). During the time period included in this analysis (2013–2022), the committee observed that both agencies included alternative and confirmatory data in approval packages across therapeutic areas, with an increase noted in the inclusion of ACD in public assessment reports for anti-cancer and immunomodulator drug products (see Figure 4-4).

Expanding the Use of Alternative and Confirmatory Data

While the committee was able to gather some evidence that ACD has been used to support a determination of substantial evidence of effectiveness, data were limited and not easily accessible. In addition to information that had to be obtained directly from FDA (see Chapter 2), the committee used a proprietary database curated by the Centre for Innovation in

NOTES: EMA = European Medicines Agency; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NASs = new active substances.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

Regulatory Science from public domain sources such as agency public assessment reports (see Appendix D for full methodology). The addition of context-specific information on whether ACD did or did not meet criteria for informing regulatory decision-making would have enabled the committee to carry out a more informed assessment of how EMA and FDA are considering the types and sources of alternative and confirmatory data for rare disease drug products.

Qualitative interviews with industry representatives suggested that there are mixed perceptions regarding the degree to which EMA and FDA

NOTES: EMA = European Medicines Agency; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NASs = new active substances; Other = other therapeutic areas not described in the top five therapeutic indications list.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

consider the use of alternative and confirmatory data in regulatory decision-making, and conflicting viewpoints about whether or not there is variability in the acceptance of these data within a given agency or between reviewers (see Appendix E for full methodology and results).

Given proven examples of success, the evolution in regulatory thinking, and advances in new trial designs and methods for data analysis, there is a growing impetus to apply and expand available opportunities for collecting and using ACD to inform researchers, sponsors, regulators, and patient groups on when and how alternative and confirmatory data have informed regulatory decision-making to ensure the integration of lessons learned from past successes and failures.

EMA and FDA can play a critical role in facilitating the use of these types of data in marketing submission applications by standardizing, documenting, and publicly sharing information to enable stakeholders to track over time how ACD have successfully and unsuccessfully informed regulatory decision-making for rare disease drug products. A publicly available and easily accessible (indexed and searchable) listing of products, coupled with standardized information on the types and sources of ACD that were considered as part of a marketing authorization application, would enable drug sponsors, patient and disease advocates, researchers, and regulators to improve the collection and use of these data for rare disease drug development going forward.

As an example, FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) reviewed a sample of past regulatory decisions from across CDRH offices to identify examples of how real-world evidence had been used by the agency to inform premarket and postmarket decision making. CDRH then issued a publicly available report (FDA, 2021a), which lays out 90 examples of submissions organized by type of device and summarizes the ways that real-world evidence has been used to inform regulatory decision-making, areas of innovation, and sources of real-world data. This resource builds on FDA guidances and provides stakeholders with concrete examples of how real-world evidence has been and can be applied for supporting FDA regulatory decision-making for medical devices.

An understanding of the opportunities as well as the gaps and inadequacies in alternative and confirmatory data would help guide data collection strategies on the part of patients, caregivers, sponsors, and researchers, and ensure that the data gathered are both relevant and robust enough to support regulatory needs.

RECOMMENDATION 4-2: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should invite the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to jointly conduct systematic reviews of submitted and approved marketing authorization applications to treat rare diseases and conditions that

document cases for which alternative and confirmatory data have contributed to regulatory decision-making. The systematic reviews should include relevant information on the context for whether these data were:

- found to be adequate, and why they were found to be adequate

- found to be inadequate, and why they were found to be inadequate

- found to be useful in supporting decision making and to what extent

Findings from the systematic reviews should be made publicly available and accessible for sponsors, researchers, patients, and their caregivers through public reporting or publication of the results. EMA and FDA should establish a public database for these findings that is continuously updated to ensure that progress over time is captured, opportunities to clarify agency thinking over time are identified, and information on the use of alternative and confirmatory data to inform regulatory decision-making is publicly shared to inform the rare disease drug development community.

FDA draft guidance, Demonstrating Substantial Evidence of Effectiveness With One Adequate and Well-Controlled Clinical Investigation and Confirmatory Evidence Guidance for Industry, states that “considerations for a safety evaluation, a benefit-risk analysis, and their impact on the acceptability of one trial with confirmatory evidence to support approval are beyond the scope of this guidance” (FDA, 2023d), suggesting that follow-on guidance on the use of alternative and confirmatory data to establish safety as well as efficacy could help further the work of the agency and provide additional clarity for drug sponsors and patient groups seeking to use these types of data for rare disease drug development. Given that draft guidances can signal agency thinking on a topic, but are not for implementation, the finalization of the 2023 draft guidance would provide much-needed assurance for FDA reviewers, drug sponsors, and patient and disease advocacy groups about FDA’s current thinking on the sources and use of alternative and confirmatory data for demonstrating substantial evidence of effectiveness.

Given the urgent need to facilitate development and approval of therapies for rare diseases and conditions, finalizing the draft guidance in a timely manner is incredibly important. Draft guidance documents need to be finalized more quickly to better facilitate and guide drug development, especially for rare diseases.

NOVEL APPROACHES FOR DATA ANALYSIS

There are several novel methods for analyzing relevant data on drug safety and efficacy that can make it possible to generate useful information for regulatory decision-making based on limited data. Further acceptance of these methods on the part of regulatory agencies and sponsors would better enable the use of alternative and confirmatory data as well as data collected through traditional randomized clinical trials for rare diseases and conditions.

Successful drug development relies on evidence that can demonstrate causality—that is, showing that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between a drug treatment and a clinical outcome. Approaches to identifying the causal effects (both safety and efficacy) of a drug treatment are based on a combination of prior knowledge, hypothesis, and correlations observed in the data (Michoel and Zhang, 2023). A major challenge for rare disease drug development is that the evidence needed to demonstrate causality may be based on limited information (e.g., data from very small clinical trials). In practice, it is often difficult to discern, based only on data acquired through traditional randomized clinical trials, whether an observed outcome is due to the drug treatment or some other factor, such as fluctuation in disease severity or other external influences. For this reason, ACD can play a critical role in informing regulatory decision-making.

At the same time, it is important to recognize that causal inferences based on observational studies or other sources of ACD are subject to bias and could produce misleading conclusions. For this reason, validating the reliability and relevance of ACD is critical for making appropriate causal inferences that can inform regulatory decision-making. Additionally, the use of various methodologies, such as Bayesian approaches, can help integrate ACD, incorporate prior knowledge and biases, consider other factors that may affect the outcome, and address confounding variables—factors that are associated with both the treatment/intervention and the outcome. For situations in which traditional randomized clinical trials are not feasible or sufficient to generate adequate evidence to inform regulatory decision-making, there are innovative approaches that can leverage information from randomized clinical trials and sources of ACD (Eichler et al., 2016).

Both FDA and EMA have issued guidance and guidelines on statistical considerations for the interpretation of superiority, non-inferiority, and equivalence trials (EMA, 2000; FDA, 2016). Generally speaking, statistical approaches involve a single-stage superiority test (weighted for effect size of the treatment and risk-benefit calculation of non-treatment) for evaluating the safety and efficacy of a test treatment under investigation. In practice, this single stage process can be viewed as a two-stage process. At the first stage, non-inferiority can be demonstrated through “not ineffectiveness”

using data collected from an RCT (or ACD or ACD plus an RCT). Once the non-inferiority of the test treatment has been established, a second test for superiority (i.e., effectiveness) of the test treatment under investigation can be carried out based on any combination of the datasets (Chow, 2020; Chow et al., 2024).

For example, this two-stage process can be implemented by combining two trials—an RCT and a real-world study—into one, which has the advantage of addressing the issue of small patient population and insufficient power in rare disease drug development. In addition, the use of ACD (instead of, or in addition to RCT data) could help maximize statistical power, could provide more accurate and reliable assessment of the treatment effect, and most importantly may shorten the development process and increase the probability of success for rare disease drug development.

For many rare diseases, there can be several competing endpoints of interest, and there are limited historical data to inform the selection of one specific primary endpoint for a specific trial. Novel methods such as Win ratio test and desirability of outcome ranking may be used to integrate evidence from multiple endpoints and address challenges associated with different types of endpoints (e.g., clinical event, functional assessment, biomarker, and patient-reported outcomes) (Pocock et al., 2012; Sandoval, 2023). For diseases that affect multiple organs and tissues and have heterogeneous clinical presentations, global tests for multiple endpoints may improve study power and provide a broad efficacy assessment for novel trials that use different endpoints for different patient subpopulations (Ramchandani et al., 2016). These tests may also allow for varying endpoints among different subsets of patients to accommodate heterogeneous clinical manifestation.

A number of novel approaches can be applied toward data analyses for rare disease drug development, a few of which are briefly described below. Such methods could be adapted for use in rare disease drug trials but require consideration and assessment for when and how such tools could be applied to inform regulatory decision-making.

Bayesian Statistical Methods

Bayesian statistical methods—an approach for learning from evidence as is accumulated—has been increasingly applied in clinical research and may be particularly well suited for certain types of clinical trials for rare diseases and conditions. Perhaps one of the more useful applications of Bayesian statistical methods for rare diseases is in the incorporation of external or Bayesian statistical methods control data (Psioda and Ibrahim, 2019). A Bayesian approach can offer a way of synthesizing alternative and confirmatory data from multiple sources (e.g., historical and external

data) into a holistic analysis to evaluate the veracity of the null or alternative hypothesis as part of the inference for the current clinical trial (Ruberg et al., 2023). Methods may also be applied to enable continuous learning throughout the course of a clinical trial and help investigators determine when to make modifications (e.g., dosing, treatment-switching, adding or dropping a treatment arm) under an adaptive trial design.

Unlike traditional frequentist statistics—a well-established approach based on statistical hypothesis testing and confidence intervals, Bayesian statistical methods are used to answer a research question by determining how likely the specified hypothesis is to be true given prior evidence about the hypothesis combined with the accumulated data from the current experiment (Berry, 2006; Ruberg et al., 2023). Bayesian statistical methods can be an effective tool for rare disease drug development as they can help reduce the number of trial participants required to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of a new therapy.

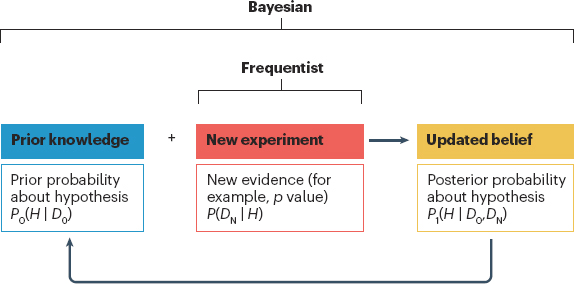

The first step in a Bayesian analysis plan is the selection of a prior probability distribution of the parameter (e.g., mean response, the variability associated with the mean response, or treatment effect size) for which one wishes to make an inference based on the observed data. Once a prior distribution is defined, another key component of the subsequent Bayesian analysis is the weight given to that prior (see Figure 4-5). A posterior probability, which described a range of likely treatment effect values as a result of current experiment, is then derived by combining information from the prior probability distribution and the newly collected data.

NOTES: A Bayesian approach defines prior knowledge (D0) about a hypothesis (H) as a prior probability (P0), which is then combined with evidence from a new experiment (DN) to determine a posterior probability (P1) of H being true.

SOURCE: Ruberg et al., Application of Bayesian approaches in drug development: starting a virtuous cycle, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 22, 235–250, 2023, Springer Nature.

For rare disease drug development, in practice, it is often difficult, if not impossible, to verify the appropriateness of the selected prior distribution due to the unavailability of existing or historical data. Results obtained from a posterior distribution with a wrong prior could be biased and hence misleading in decision making regarding the review and approval of the test treatment under investigation (Ruberg et al., 2023). See Box 4-5 for a use case that applied multiple priors from historical data. Some trials have used non-informative priors to avoid the difficulties in specifying a prior distribution for the treatment effect or other parameter. One example was the PREVAIL II trial of ZMapp conducted during the 2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa (The PREVAIL II Writing Group, 2016). Bayesian methods were applied in PREVAIL II to accommodate the data monitoring plan. After 20 patients were enrolled, data were analyzed after every 2 patients randomized to see if the trial could stop early, because of difficulties in recruiting, trial conduct, and drug shortages. The issues of prior distribution selection were thereby avoided. There are other applications of Bayesian methods that minimize the difficulties of prior selection, which could be considered for use in rare disease drug trials.

In rare disease drug development, a hybrid two-stage design can consist of an RCT or a single-arm study at the first stage and a real-world evidence study at the second stage. The first stage is used to demonstrate that the test treatment is not-ineffective with a small, but reasonable sample size,

BOX 4-5

Application of Bayesian Method: Hypoxic Ischaemic Encephalopathy

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy is a rare condition that occurs in newborns in which the brain does not receive enough oxygen or blood flow for a period of time, which can lead to potential organ damage. Multiple randomized clinical trials had demonstrated the benefit of therapeutic hypothermia within 6 hours of birth, but there were practical challenges with implementing such a rapid intervention. To address the question of whether therapeutic hypothermia could be effective at later time points, a Bayesian approach was applied that borrowed from historical data by considering three priors: a skeptical prior, an enthusiastic prior, and a neutral prior. The results of the study indicated that therapeutic hypothermia initiated 6–24 hours after birth reduced mortality and disability compared with the non-cooling standard of care.

__________________

SOURCE: Laptook et al., 2017.

while the second stage uses the Bayesian approach in conjunction with the technique of propensity score matching to demonstrate that the test treatment is effective by borrowing information from supplemental data (Chow et al., 2024).

The use of Bayesian methods in clinical trials offers potential benefits, particular for rare disease drug development, but they remain relatively underused, perhaps due to a lack of acceptance and familiarity on the part of regulators and sponsors (Ruberg et al., 2023). There are already in place the regulatory flexibilities for EMA and FDA to consider the use of ACD. Additional flexibilities on the part of EMA and FDA in allowing a two-stage process for demonstrating effectiveness (demonstrating no ineffectiveness first and then demonstrating effectiveness at the second stage) would likely help expand the use of these tools in drug development.

FDA held a public workshop in March 2024, “Advancing the Use of Complex Innovative Designs in Clinical Trials: From Pilot to Practice,” and plans to publish draft guidance on the use of Bayesian methodology in clinical trials by the end of 2025 (FDA, 2023i). The workshop focused on the use of external data sources, Bayesian statistical methods, and simulations in complex innovative trial designs as well as on trial implementation (FDA, 2024a). In an FDA newsletter, the agency notes that Bayesian methods can be particularly useful for ultra-rare diseases because they allow for incorporating prior information and adapting the design more easily (FDA, 2023i). In addition, Bayesian methods can be helpful in using information from an adult population and applying it to a pediatric population (FDA, 2023i).

Network Meta-Analysis

Network meta-analysis (NMA) is a statistical approach that enables the simultaneous comparison of multiple interventions by combining evidence from direct and indirect treatment comparisons across trials (Rouse et al., 2017). This approach may be particularly valuable in the context of rare diseases for which limited patient populations often make traditional head-to-head RCTs impractical or unfeasible.

Drug development for rare diseases presents unique challenges, notably the difficulty of assembling large and diverse patient populations for RCTs, which is considered the best available standard for assessing treatment efficacy. The scarcity of patients often results in insufficient statistical power and may preclude the use of traditional RCTs altogether (Pizzamiglio et al., 2022). NMA addresses these challenges by efficiently pooling data from multiple smaller studies. This allows for the consolidation of evidence from diverse sources, thereby enhancing the statistical power and potentially reducing the time and cost associated with drug development (Tonin et al., 2017).

Furthermore, NMAs can help address the issue of comparing multiple treatments in situations where some treatments have never been directly compared in a clinical trial. By synthesizing both direct and indirect treatment comparisons, NMAs provide a more comprehensive view of the treatment landscape (Rouse et al., 2017; Tonin et al., 2017). This is crucial for rare diseases where limited patient numbers make it unfeasible to conduct multiple direct comparison trials. NMAs thus facilitate a better understanding of the relative effectiveness and safety of various treatments, guiding health care professionals in making informed decisions for patient care (Tonin et al., 2017).

To strengthen the reliability of NMAs, particularly when RCT data are sparse or absent, ACD collected through patient registries, observational studies, historical trial data, and non-randomized studies are often integrated to provide a fuller picture of treatment effects. The integration of these data requires robust statistical methods to adjust for potential biases and differences among data sources and to construct a more complete and nuanced analysis. For example, in the case of Friedreich’s ataxia, NMAs were instrumental in aggregating data from numerous small-scale studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the disease progression and the potential cognitive impact of various interventions. By pooling evidence from multiple sources, these analyses have helped to overcome the limitations of individual studies with small sample sizes (Harding et al., 2021; Naeije, 2022). The insights gained from NMAs have informed the development of treatment guidelines and have been considered by FDA when evaluating new therapies targeting neurological outcomes in this rare disease. This approach has facilitated a more evidence-based decision-making process, ensuring that patients with Friedreich’s ataxia have access to the most promising and well-studied treatments.

NMAs that incorporate evidence from case reports and small observational studies have also been pivotal in supporting drug approvals for specific subtypes of congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS) (Della Marina et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2021). Given the extremely rare nature of these conditions, conducting traditional clinical trials is often not feasible. In such cases, FDA has relied on NMAs to assess the safety and efficacy of treatments like eculizumab for specific CMS subtypes where conventional clinical trial data is scarce. NMAs have enabled regulators to make informed decisions about the approval of targeted therapies for these rare conditions, ultimately improving patient outcomes and quality of life. By synthesizing evidence from diverse sources, NMAs provide a more comprehensive understanding of treatment effects, enabling regulators to make more informed decisions about whether innovative therapies make a meaningful difference in improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

FDA and EMA both use NMAs to inform regulatory decisions, yet their approaches exhibit some differences. FDA has developed draft guidance focusing on the use of RCT meta-analyses in evaluating drug safety, emphasizing the importance of selecting candidate trials that are of high quality (FDA, 2018b). This reflects a more cautious stance toward ensuring trial quality and similarity for indirect comparisons. Conversely, while specific EMA guidelines on NMAs were not highlighted in the search results, participants of qualitative interviews noted that real-world evidence and historical data may be more commonly considered in the European context, especially for rare diseases (see Appendix E for full methodology and results). Both agencies grapple with the challenge of defining the threshold of evidence quality needed for drug approvals without RCTs, but direct comparisons of their use of NMA results in decision making are not readily available. While FDA’s guidance is more explicit in its focus on RCT data for safety NMAs, EMA’s approach may implicitly encompass a broader spectrum of evidence sources. Further exploration is warranted to clarify these differences and how they may affect the evaluation of NMA evidence in the regulatory context.

Randomization-Based Inference

Randomization-based inference (RBI) is an analytical framework for clinical trials that accounts for any variation that might be intrinsic to the process of randomization or treatment allocation itself (i.e. it assesses the treatment effect on outcome under all possible randomization assignments) (Berger et al., 2021; Li and Izem, 2022). The various approaches include re-randomization and permutation methods. Although less pervasive and more computationally intense than traditional approaches, it is particularly useful in the context of the limited patient populations found with rare diseases (Ravichandran et al., 2024).

For rare disease trials, confounding may appear in the presence of linear time trends due to a long study duration or use of non-random approaches, such as minimization, wherein unspecified covariates are also subject to temporal trends (Li and Izem, 2022). More importantly, most conventional trials are built on a population-based inference assumption or a random sampling from a population of interest that is frequently inappropriate or infeasible for rare diseases. An advantage of RBI is that it does not require any distributional assumptions about the outcome and allows for control and an exact test of type 1 error rate. RBI reliably increases a trial’s statistical power and ability to discern average treatment effect in the absence of model-based assumptions (Carter et al., 2023; Chipman, 2023).

A central tenet of RBI approaches is that the randomization approach is itself a key driver of statistical inference, and this underlies a growing

recognition of its utility as supplemental data to trials based on likelihood-based testing (Berger et al., 2021). Furthermore, RBI is applicable to any randomization approach and underlying data type (e.g. categorial or continuous). It often leverages Monte Carlo simulation and tests a null hypothesis that an orphan drug has no effect on the treatment and control groups. Procedurally, the data are fixed at the observed values and re-randomization is performed using the original treatment assignment approach wherein each new assignment is treated independently. This process is repeated a significant number of times (> 10,000), and the p-value is estimated by the proportion of re-randomized trials wherein the treatment effect attributable to the placebo was larger than the originally observed treatment effect (The World Bank Group and DIME Analytics, n.d.).

RBI has been a successful method for study design. For example, the study of Nexviazyme for Pompe disease used novel randomization methods for a trial that led to marketing authorization (see Box 4-6).

In a 2015 guideline from EMA, recommendations against deterministic treatment allocation approaches were put forward, and randomization tests were strongly encouraged to mitigate Type 1 error (EMA, 2015). On the other hand, FDA’s 2019 guidance on adaptive trial design includes the following language: “Covariate-adaptive treatment assignment techniques do not directly increase the Type I error probability when analyzed with the appropriate methodologies (generally randomization or permutation tests)” (FDA, 2019a).

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology

Quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) is a type of drug and disease computational modeling that integrates drug features (e.g., dose, regimen, potency) with cellular, molecular, and pathophysiological data. A fundamental advantage of QSP for rare disease drug development programs is the potential to magnify insights based on multiple sources of alternative and confirmatory data which can be used to inform research and development programs from early-stage drug discovery through marketing authorization application. QSP can help mitigate risks to patients by virtually modeling variance or uncertainty and also has applications for identifying, interrogating, and validating biomarkers.