Regulatory Processes for Rare Disease Drugs in the United States and European Union: Flexibilities and Collaborative Opportunities (2024)

Chapter: 2 FDA Flexibilities, Authorities, and Mechanisms

2

FDA Flexibilities, Authorities, and Mechanisms

FDA is adapting to this evolving world by embracing both the challenges and opportunities we face. We are leveraging flexibilities in our regulatory pathways to enable breakthroughs in medical science that can be translated into medical products that improve health outcomes. We are reshaping our regulatory processes and creating a nimble workforce that adapts to new technologies, medical products, biomedical science, food science, and public health.1

Robert Califf,

Commissioner of Food and Drugs

(Committee on Oversight and Accountability:

U.S. House of Representatives, 2024)

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has authority under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act)2 and Public Health Service Act3 to regulate medical products and devices to ensure that they are safe and effective for their intended use. In addition to protecting the public health through regulation, the FDA mission also

___________________

1 Robert Califf, testimony to Committee on Oversight and Accountability. Available at https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/FDA-House-Oversight-and-Accountability-Testimony.pdf (accessed June 26, 2024).

2 P.L. 75–717. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (June 25, 1938).

3 P.L. 78–410. Public Health Service Act (July 1, 1944).

states that it is “responsible for advancing the public health by helping to speed innovations that make medical products more effective, safer, and more affordable and by helping the public get the accurate, science-based information they need to use medical products and foods to maintain and improve their health” (FDA, 2023p).

Chapter 1 highlighted some of the many challenges faced by drug sponsors, researchers, and patients when it comes to generating evidence to support the approval of a drug to treat rare disease and conditions. The review and approval of such products by FDA likewise requires complex judgments, often based on limited information, about what it means for a drug product to be safe and effective.

FDA has long recognized the need to apply regulatory flexibility in the review and approval of marketing authorization applications. Analyses of noncancer orphan drugs have shown that over time FDA has continued to apply flexibility in the review of certain applications for orphan drug products (Sasinowski, 2011; Sasinowski et al., 2015; Valentine and Sasinowski, 2020). FDA’s 2023 guidance for industry, Rare Diseases: Considerations for the Development of Drugs and Biological Products, reiterates the need for flexibility when it comes to applying statutory standards for drug development programs to rare disease, stating, “FDA has determined that it is appropriate to exercise the broadest flexibility in applying the statutory standards, while preserving appropriate standards of safety and effectiveness, for products that are being developed to treat severely debilitating or life-threatening rare diseases” (FDA, 2023l).

As specified in the statement of task, this report focuses on the flexibilities, authorities, and mechanisms available to regulators that are applicable to rare diseases or conditions. Where available, data are provided on the impact of these activities. For more general information on the FDA drug approval process please see FDA (2022b).

This chapter is organized into sections on the following topics: drug review and approval, designation for rare disease products, expedited regulatory programs, inclusion of pediatric populations, stakeholder engagement, rare disease programs, and transparency.

DRUG REVIEW AND APPROVAL

Before initiating a clinical trial of a drug or biological product in the United States, a sponsor generally must first submit an investigational new drug (IND) application to FDA. The proposed clinical trial is generally based on pre-clinical testing and includes plans for testing the drug in humans. FDA reviews the IND application to, among other things, ensure that the proposed clinical trials do not place trial participants at unreasonable risk of harm, and that the protocol and informed consent will be

reviewed by an institutional review board (IRB) that meets FDA regulatory standards (FDA, 2014a). Although the IRB is responsible for reviewing the informed consent for all clinical trials under its jurisdiction, there are situations in which an FDA review of an informed consent document in addition to IRB review is particularly important to determine whether a clinical trial may safely proceed under 21 CFR part 312 (FDA, 2014a).

After carrying out clinical trials, FDA recommends, but does not require, that the drug sponsor meet with the agency before submitting a formal new drug application (NDA) or biologics license application (BLA); these applications include pre-clinical and clinical evidence for demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of the proposed drug or biological product. After FDA receives an NDA or BLA, the agency has 60 days to decide whether to file it for review. If FDA files the NDA or BLA, an FDA review team will evaluate the drug’s safety and effectiveness. Drug products and some biological products are assigned to the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), while other biological products (including gene therapies) and related products, including blood, vaccines, and allergenics, are assigned to the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). Within CDER, applications are assigned to the Office of New Drugs (OND), and then to a specific office and division within the OND based on the therapeutic area. Within CBER, applications are assigned to one of three program offices (the Office of Therapeutic Products [OTP], Office of Vaccines Research and Review [OVRR], or Office of Blood Research and Review [OBRR]) and then to a specific office and division within the OTP, OVRR, or OBRR, as appropriate, based on the treatment modality. Typically, the relevant office and division will have already been involved in the IND process. The FDA review team evaluates the NDA or BLA and decides whether to grant marketing approval (see Figure 2-1).

As part of the review process, FDA may seek external input through advisory committees, which include representatives from academia, industry, and patient groups. Other external input throughout the drug development lifecycle is typically collected through established governmental programs, public comment, or through special government employees. This input may be used to inform FDA’s decision but the ultimate authority and decision making resides with FDA. While the regulatory process is the same for rare and common conditions, rare disease drug development is often dependent on a limited pool of experts, many of whom may be directly involved in drug development trials and considered to have a conflict of interest. This can make it challenging to populate advisory committees with people who have relevant expertise. Additionally, as described in Chapter 4, there are a number of considerations for data sourcing, trial design, and methodologies that are particularly relevant for rare disease marketing authorization applications.

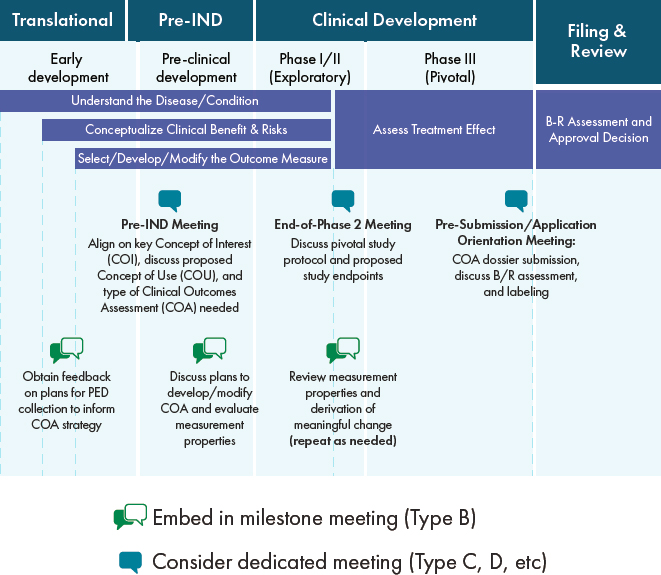

NOTES: B-R = benefit/risk; COA = clinical outcomes assessment; COI = concept of interest; COU = concept of use; PED = patient experience data; Pre-IND = preinvestigational new drug application.

SOURCE: Adapted from Biotechnology Innovation Organization, 2022.

FDA strives to be transparent when sharing relevant documents following drug approval, such as letters, reviews, labels, and patient package inserts. At the same time, FDA is required by law to review and protect certain information from being released to the public, including confidential commercial information, trade secrets, and personal privacy information. FDA has stated that commercial information “is valuable data or information which is used in a business and is of such type that it is customarily held in strict confidence or regarded as privileged” (FDA, 2018c) There is an inherent tension between the legal limitations regarding the release of what could be considered confidential commercial information and FDA’s obligation to share relevant information in the interest of public health. The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 requires that new molecular entities/new biological entities action packages be published on CDER’s web page within 30 days after approval (see Table 2-1). However,

TABLE 2-1 Components of an Action Package for an NDA or BLA

| Component | Examples |

|---|---|

| FDA-generated documents related to review of the marketing authorization application | Approval letter Summary minutes for meetings held with applicant Summary basis of regulatory action |

| Documents pertaining to the format and content of the application generated during the drug development phase (investigational new drug application) | Package insert |

| Certain documents submitted by the applicant |

NOTES: BLA = biologics license application; NDA = new drug application.

SOURCE: FDA, 2022a.

FDA is not required to publish complete response letters—a written response sent to sponsors to indicate that FDA’s review of a marketing authorization application has been completed and the application is not ready for approval. Complete response letters usually describe “all of the specific deficiencies that the agency has identified in an application” (FDA, 2008).

Benefit–Risk Assessment

As articulated in the 2024 National Academies report, Living with ALS, there are trade-offs between enabling patient access to new medications and the degree of uncertainty when it comes to the assessment of benefit and risks for a given drug (NASEM, 2024). There are several factors involved in the assessment of the benefits and risks of a particular drug, including the clinical context, the availability of other treatments, and the seriousness of the condition (see Box 2-1). FDA guidance for industry, Rare Diseases: Considerations for the Development of Drugs and Biological Products (FDA, 2023l), notes that “a feasible and sufficient safety assessment is a matter of scientific and regulatory judgment based on the particular challenges posed by each drug and disease, including patients’ tolerance and acceptance of risk in the setting of unmet medical need and the benefit offered by the drug.” The benefit–risk assessment also involves an evaluation of the degree of uncertainty in the identified risks and benefits. For example, a small trial may not detect certain adverse events, or it may overestimate the effect of the drug. FDA guidance Benefit–Risk Assessment for New Drug and Biological Products (FDA, 2023c) states that a higher degree of uncertainty is common in rare disease drug development due to limitations on study size and that when drugs are being developed for serious diseases with few or no approved therapies, “greater uncertainty or greater risks

BOX 2-1

Benefit–Risk Assessment

- “Benefit–risk assessment is an integral part of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) regulatory review of marketing applications for new drugs and biologics. These assessments capture the Agency’s evidence, uncertainties, and reasoning used to arrive at its final determination for specific regulatory decisions. Additionally, they serve as a tool for communicating this information to those who wish to better understand FDA’s thinking” (FDA, 2022c).

- All drugs can have adverse effects, so the demonstration of safety requires a showing that the benefits of the drug outweigh its risks (Fain, 2023; FDA, 2023c).

- Benefit–risk assessment is integrated into FDA’s regulatory review of marketing applications for new drugs (Fain, 2023).

- Section 505(d) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act requires FDA to “implement a structured risk-benefit assessment framework in the new drug approval process” and provides that this requirement does not alter the statutory criteria for evaluating an application for marketing approval of a drug (Fain, 2023).

- FDA uses scientific assessment and regulatory judgment to determine whether the drug’s benefits outweigh the risks, and whether additional measures are needed and able to address or mitigate this uncertainty (Fain, 2023; FDA, 2023c).

__________________

SOURCES: Fain, 2023; FDA, 2022c, 2023c.

may be acceptable provided that the standard for substantial evidence of effectiveness has been met.”

In the case of serious rare diseases, FDA may thus exercise regulatory flexibility by accepting clinical trials that have smaller sample sizes. Accepting smaller sample sizes for serious rare diseases places even greater importance on maximizing the trial’s potential to provide interpretable scientific evidence about the drug’s benefits and risks in order to be respectful of patients’ willingness to participate in clinical trials. Patient contribution is optimized in clinical trials (and particularly in small sample size studies) by minimizing bias and maximizing precision with trial design features such as randomization, blinding, enrichment procedures, and adequate trial duration (FDA, 2023c).

Substantial Evidence of Effectiveness

Substantial evidence of effectiveness is defined in section 505(d) FD&C Act as:

evidence consisting of adequate and well-controlled investigations, including clinical investigations, by experts qualified by scientific training and experience to evaluate the effectiveness of the drug involved, on the basis of which it could fairly and responsibly be concluded by such experts that the drug will have the effect it purports or is represented to have under the conditions of use prescribed, recommended, or suggested in the labeling or proposed labeling thereof.4

FDA has interpreted substantial evidence of effectiveness as generally requiring at least two adequate and well-controlled clinical investigations, each of which is convincing on its own (FDA, 2019a). Requiring two adequate and well-controlled clinical trials allows for independent substantiation of study results and protects against the possibility that a chance occurrence in one study would lead to an erroneous conclusion about the drug’s effectiveness (FDA, 1998, 2019a; Freilich, 2024). However, there is regulatory flexibility available in some circumstances for the amount and type of evidence needed to meet the substantial evidence standard, as described further in the FD&C Act and FDA guidance documents and discussed below.

In 1997, Congress amended the FD&C Act to clarify that substantial evidence of effectiveness could also consist of a single adequate and well-controlled study and confirmatory evidence “if [FDA] determines, based on relevant science, that data from one adequate and well-controlled clinical investigation and confirmatory evidence (obtained prior to or after such investigation) are sufficient to establish effectiveness.”5

This clarification reflected FDA’s then-current thinking given the rapidly evolving science and practice of clinical research and drug development. In 1998, FDA released subsequent guidance6 for industry, Providing Clinical Evidence of Effectiveness for Human Drug and Biological Products (FDA, 1998), to share the agency’s thinking on the quantity and quality of data

___________________

4 21 U.S.C. § 355(d).

5 21 P.L. 105–115. Food and Drug Modernization Act (November 21, 1997).

6 FDA develops guidance documents to share FDA’s current thinking on a topic (FDA, 2023f). These documents are not legally binding for FDA or the public. To develop a guidance document, FDA first has the option to seek input from external stakeholders. FDA then prepares a draft version of the document which is posted publicly along with a notice in the Federal Register. The draft guidance is then open to public comment. FDA then reviews the comments and makes any necessary edits before posting the finalized guidance document (21 CFR §10.115).

that could be used for demonstrating effectiveness of drugs.7 In this guidance, FDA provided several illustrations of the “types of evidence that could be considered confirmatory evidence, with a specific focus on adequate and well-controlled trials of the test agent in related populations or indications, as well as a number of illustrations of a single adequate and well-controlled trial supported by convincing evidence of the drug’s mechanism of action in treating a disease or condition” (FDA, 2023f). For example, a pediatric indication might be approved based on a study on adults if the pathophysiology and drug effect are similar between the populations.

In December 2019, FDA issued draft guidance, Demonstrating Substantial Evidence of Effectiveness for Human Drug and Biological Products, which complemented and expanded on the 1998 guidance. The new draft guidance stated, “Although FDA’s evidentiary standard for effectiveness has not changed since 1998, the evolution of drug development and science has led to changes in the types of drug development programs submitted to the Agency. Specifically, there are more programs studying serious diseases lacking effective treatment, more programs in rare diseases, and more programs for therapies targeted at disease subsets” (FDA, 2019a). Consequently, the 2019 guidance lists several illustrative examples of the types of evidence that could be considered as confirmatory of a single adequate and well-controlled study. Those examples included: (1) data from a single adequate and well-controlled study that demonstrated the drug’s effectiveness in another closely related approved indication; (2) data providing strong mechanistic support; (3) natural history data from the disease, and (4) scientific knowledge about the effectiveness of other drugs in the same pharmacological class. A single study could be sufficient for demonstrating effectiveness if the study is a large multicenter, adequate, and well-controlled trial and “the trial has demonstrated a clinically meaningful and statistically very persuasive effect on mortality, severe or irreversible morbidity, or prevention of a disease with potentially serious outcome and confirmation of the result in a second trial would be impractical or unethical” (FDA, 2019a).8

In 2023, FDA issued a draft guidance, Demonstrating Substantial Evidence of Effectiveness with One Adequate and Well-Controlled Clinical Investigation and Confirmatory Evidence, which offers further clarification on when one study and confirmatory evidence may be sufficient for establishing effectiveness (FDA, 2023f). The guidance identifies types of confirmatory evidence that could be used to supplement one clinical investigation; FDA notes that the list is not exhaustive, and that each application is considered on a case-by-case basis. The types of confirmatory evidence

___________________

7 This sentence was edited after release of the prepublication version of the report to reflect the nature of data used.

8 This section was edited after release of the prepublication version of the report to clarify when a single trial approach could be sufficient for demonstrating effectiveness.

listed include clinical evidence from a related indication, mechanistic or pharmacodynamic evidence, evidence from a relevant animal model, evidence from other members of the same pharmacological class, natural history evidence, real-world data, and evidence from expanded access use of an investigational drug (see Chapter 4).

FDA conducts a thorough review of an application to determine whether the submitted data constitutes substantial evidence of effectiveness. FDA examines both final summaries and data from nonclinical and clinical studies, from which it determines the safety and effectiveness of the product through its own independent analysis. The review team replicates the applicant’s analyses and, if necessary, conducts additional analyses to further inform the efficacy assessment (Bugin, n.d.).

Conclusion 2-1: While the statutory requirements for drug approval for rare diseases and conditions are the same as for non-rare diseases or conditions, FDA has long recognized the need to apply regulatory flexibility in the review and approval of marketing authorization applications.

DESIGNATION FOR RARE DISEASE PRODUCTS

As discussed in Chapter 1, FDA has the authority to grant orphan drug designation for products that are used to prevent, diagnose, or treat a rare disease or condition. Additionally, FDA can award “rare pediatric disease” designation for drug applications that meet certain criteria.9 These designation programs, which are further described below, provide incentives for sponsors to develop drugs to treat rare diseases and conditions.

Orphan Drug Designation

The orphan drug designation is an FDA incentive that began in 1983 following the enactment of the Orphan Drug Act, with the goal of stimulating the development of drugs and biological products for rare diseases by lessening the financial burdens associated with orphan drug development. A drug may qualify for orphan-drug designation (ODD) if the targeted disease or condition affects fewer than 200,000 individuals in the United States at the time of the sponsor’s request, or if it affects more than 200,000 individuals but there is no reasonable expectation that the cost of developing a drug for the condition would be recovered by sales of the drug.10 To be eligible for ODD, a drug or biological product must be for a distinct rare disease or condition. FDA determines what the distinct disease or condition is by considering such factors as the pathogenesis of the condition, course

___________________

9 P.L. 112–144. Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (July 9, 2012).

10 21 CFR §316.20(b)(8); 21 U.S.C. § 360bb(a)(2).

of the condition, prognosis of the condition, and resistance to treatment.11 These factors are assessed in the context of the specific drug seeking ODD.

A sponsor can receive multiple designations for the same drug if it can be shown to treat more than one distinct disease or condition. A sponsor can also receive ODD for its version of a drug that is otherwise the “same drug” as an already approved drug for the same disease or condition as long as the sponsor can present a plausible hypothesis that its drug may be clinically superior to the first drug.12

A sponsor may receive ODD for a drug designed to treat an “orphan subset”13 of individuals with a disease that affects more than 200,000 people if it can be demonstrated that the subset affects less than 200,000 people in the United States and that the remaining individuals with the disease would not be appropriate candidates due to some property of the drug.14 To be considered for ODD under this “orphan subset” provision, the demonstration that other patients would not be appropriate candidates must be based on pharmacologic or biopharmaceutical properties of the drug, or previous clinical experience with the drug.15 For example, ODD could be granted if data demonstrate that the drug is only effective for patients with a certain biomarker, or that the toxicity of the drug makes it appropriate only for patients who do not respond to standard, less toxic treatments.16 FDA has clarified that an orphan subset does not refer to a clinically distinguishable subset of persons with a particular condition; eligibility for ODD under an orphan subset must be based on a property of the drug itself, not a subset of patients.17 A product targeted at just the pediatric population may be eligible for ODD in a number of ways (FDA, 2018a). First, if the disease is rare in the overall population, any product may be eligible. Second, if the disease is common in the general population, a product may be eligible for ODD if the affected pediatric population is less than 200,000 and is a valid orphan subset, meaning that the product would not be appropriate for use in the adult population owing to some property or properties of the drug; this would be considered an orphan subset designation. Third, a product may be eligible for ODD if the disease in the pediatric population is a different disease than in the adult population and the affected pediatric population is less than 200,000.

___________________

11 78 FR 35117(III)(A).

12 21 CFR §316.20(a).

13 78 FR 35117(III)(A) at 35119, explaining that: “orphan subset is a regulatory concept specific to the Orphan Drug regulations, and that it does not simply mean any medically recognizable or clinically distinguishable subset of persons with a particular disease or condition (as the term ‘medically plausible’ in this context may have been erroneously interpreted to imply).”

14 21 CFR §316.20(b)(6).

15 21 CFR §316.3(b)(13).

16 78 FR 35117(III)(A).

17 78 FR 35117(III)(A).

Process

Orphan drug designation is a separate process from drug approval or licensing. Sponsors seeking ODD submit a request to FDA that includes an explanation of the rare disease or condition the drug is intended to treat along with data (e.g., clinical, in vivo, and in vitro) to support the scientific rationale for using the drug in this population.18 FDA reviews the request to assess whether the drug product meets the criteria for ODD and will send the sponsor a designation letter granting ODD, a deficiency letter that requests additional information, or a denial letter (FDA, 2023h). In 2017, according to FDA’s Orphan Drug Modernization Plan, the agency aimed to complete all new ODD reviews within 90 days of receipt (FDA, 2017b).

Benefits

ODD qualifies sponsors for incentives which include tax credits of 25 percent of qualifying clinical trial expenses, a waiver of the user fee ($4 million for fiscal year 2024) (FDA, 2024o), and potentially 7-year market exclusivity—upon approval for an indication or use within the scope of the designation (Michaeli et al., 2023).19,20 In addition, the Orphan Drug Act established the Orphan Product Grants Program to provide funding for developing products for rare diseases or conditions. The statutory authority for the Orphan Products Grants Program has been expanded to include support for “prospectively planned and designed observational studies and other analyses conducted to assist in the understanding of the natural history of a rare disease.”21

Approvals of Drugs with Orphan Drug Designation

Prior to the Orphan Drug Act, few drugs were approved by FDA for rare diseases and conditions (Asbury, 1991). During the last 40 years, over 6,300 drugs have received ODD for over 1,000 rare diseases. Of the ODDs granted by FDA, 882 resulted in at least one drug approval for 392 diseases (Fermaglich and Miller, 2023). As of 2022, between 4 and 6 percent of rare diseases had an approved drug, while between 11 and 15 percent had received an ODD (Fermaglich and Miller, 2023).

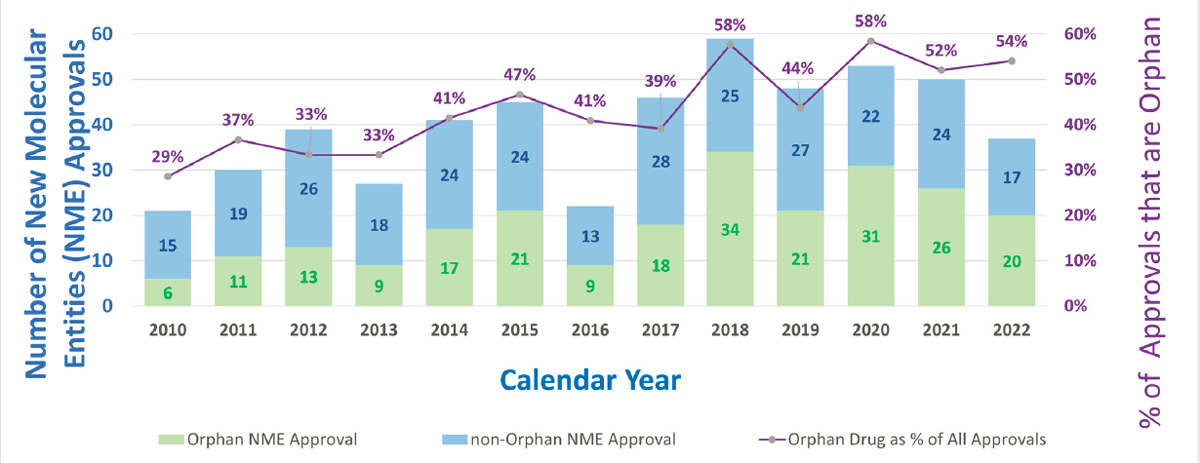

In 2010, CDER approved six new molecular entities with ODD, representing 29 percent of approved new products. In 2022, CDER approved 20 new molecular entities for orphan conditions, constituting 54 percent of

___________________

18 21 CFR §316.20.

19 This sentence was edited after release of the prepublication version of the report to more accurately reflect 21 USC § 360cc – Protection for drugs for rare diseases or conditions.

20 21 U.S.C §360cc(a).

21 21 U.S.C §360ee(b).

NOTE: CDER = Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

SOURCE: Presented to the Committee by Kerry Jo Lee, on November 6, 2023.

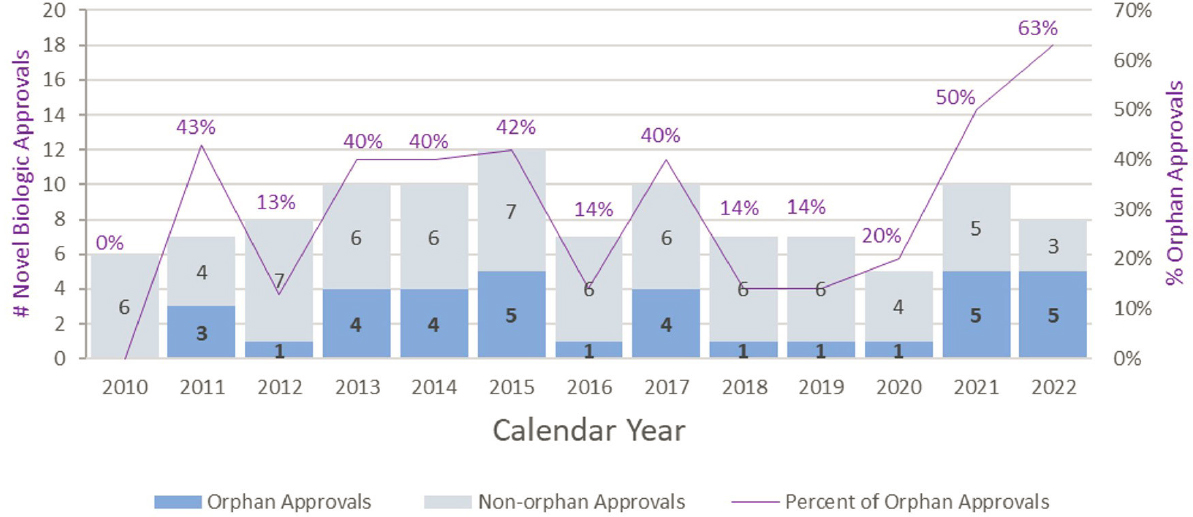

all center approvals (see Figure 2-2). CBER product approvals followed a similar trend, increasing from zero ODD approvals in 2010 to five in 2022, constituting 63 percent of all center approvals (see Figure 2-3). Overall, from 2010 to 2022, the number of orphan drug approvals increased in both number and percentage of the total approved new products for both CDER and CBER, with orphan drugs making up over half of approved new products for both centers in 2021 and 2022.

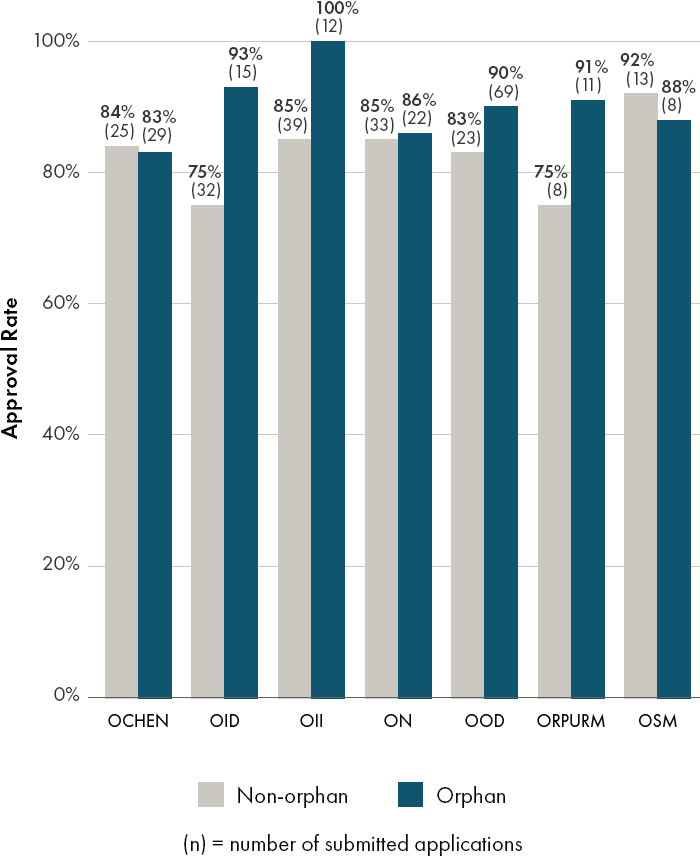

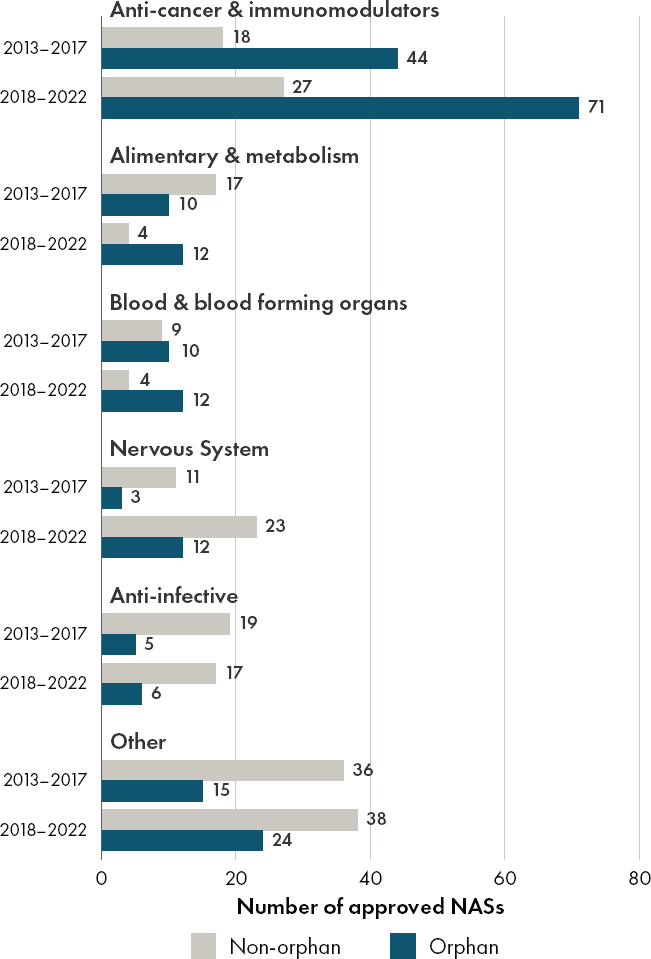

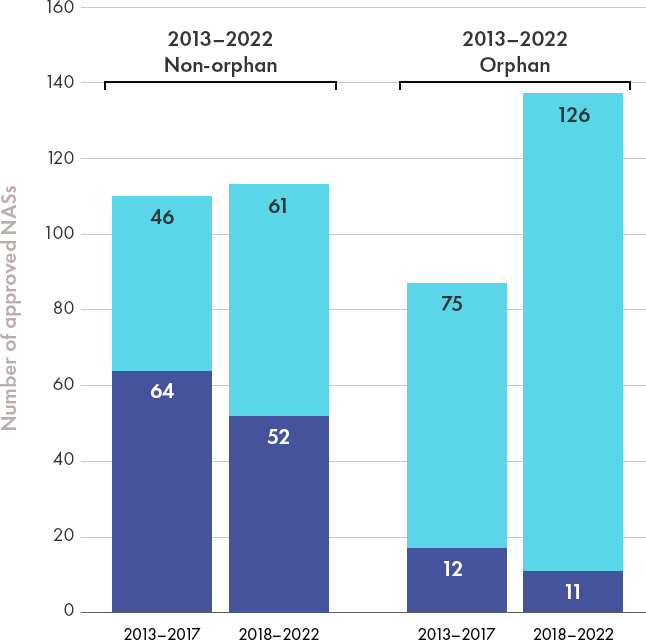

To understand the rates of FDA approvals for non-orphan and orphan drug products over time, the committee commissioned an analysis of marketing submissions, regulatory orphan designations, and marketing approvals of new drug products from 2013–2022 using new drug applications and biologics license applications (types 1 and 1,4). Due to a lack of available data on approval and non-approval rates, the committee requested information about new drug products received from 2013–2022. Data from 2015–2020 were obtained directly from the agency for CDER and CBER. Additional data on the therapeutic areas and use of expedited review pathways were obtained from agency public assessment reports (see Appendix D for full methodology). Overall, approval rates for orphan drug product applications received between 2015 and 2020 are higher than for non-orphan drug products at nearly all FDA offices, with approval rates ranging from 83 percent (Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology, and Nephrology) to 100 percent (Office of Immunology and Inflammation) (see Figure 2-4). Despite the increasing number of ODD and associated drug approvals, much of the progress has been concentrated in a few therapeutic areas. Between 2013 and 2022, a large portion of orphan drug approvals were for anti-cancer and immunomodulator treatments, followed by alimentary and metabolism treatments and the blood and blood forming organs treatments (see Figure 2-5).22

Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher Program

The rare pediatric disease priority review voucher (PRV) program, established in 2012 under section 908 of the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA), was designed to incentivize the development of certain new drugs or biologics to prevent or treat rare diseases that affect pediatric populations.23 Section 908 of FDASIA defines a rare pediatric disease as “a serious or life-threatening disease in which the serious or life-threatening manifestations primarily affect individuals aged from birth to 18 years, including age groups often called neonates, infants, children, and adolescents,” and the disease is a rare disease or condition within the meaning of section 526 of the FD&C Act.24 Under this program,

___________________

22 This section was edited after release of the prepublication version of the report to more accurately describe the data requested and received.

23 21 U.S.C. § 360ff.

24 21 U.S.C. § 360ff(a)(3).

NOTES: These data exclude in vitro diagnostic products, reagents, and intermediate biological products approved for further manufacture, such as source plasma. CBER = Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

SOURCE: Presented to the Committee by Julienne Vaillancourt, on November 6, 2023.

NOTES: CDER = Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; OCHEN = Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology and Nephrology; OID = Office of Infectious Diseases; OII = Office of Immunology and Inflammation; ON = Office of Neuroscience; OOD = Office of Oncologic Diseases; OROURM = Office of Rare Diseases, Pediatrics, Urologic and Reproductive Medicine; OSM = Office of Specialty Medicine.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024; data directly provided by FDA.

NOTES: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NASs = new active substances; Other = other therapeutic areas not described in the top five therapeutic indications list.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

sponsors who receive approval for a drug to treat a rare pediatric disease may qualify for a voucher for priority review of a subsequent product (FDA, 2019d). Priority review generally means a marketing authorization submission will be reviewed by FDA in 6 months rather than the standard 10-month period review time. The sponsor may transfer or sell the voucher to another sponsor. The program has been renewed by Congress in the past, typically for 4 years at a time. Under current legislation, the rare pediatric disease designation PRV program begins to sunset after September 30, 2024 (FDA, 2024q).

Process

FDA’s draft guidance for industry Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Vouchers provides information on implementation of this program (FDA, 2019d). After a sponsor submits a request to FDA for rare pediatric disease designation the agency decides whether to grant the designation and whether to designate the marketing application as a “rare disease product application.” If a sponsor submits the designation request at the same time as a request for ODD or fast-track review, the “review clock” is set at 60 days.25 FDA will accept requests for rare pediatric disease designations at other times as long as requests are received prior to a filing of the NDA or BLA; these requests do not have a statutory review goal date. There are instances in which a drug may qualify for rare pediatric disease designation but not qualify for ODD and instances where a drug may qualify for ODD but not qualify for rare pediatric disease designation (FDA, 2019d). A rare pediatric disease PRV may be issued to a sponsor at the time of marketing approval if the application for the drug meets the criteria in section 529 of the FD&C Act (FDA, 2019d) and entitles the holder to priority review of an application regardless of whether the subsequent product is indicated for a rare disease.26 Sponsors also have the option of requesting a PRV independently of submitting a designation request for a rare pediatric disease.

Benefits

Drug development is a costly and time-consuming process, including the time it takes for a drug marketing authorization submission to be reviewed by regulators. A PRV helps reduce the review time for a new drug application, which can help a sponsor bring a product to market sooner. PRVs can be used by the sponsor of the original product or sold to another

___________________

25 21 U.S.C. § 360ff(d)(3).

26 21 U.S.C. § 360ff(b).

party; purchase prices have ranged from $67.5 million to $350 million (GAO, 2020).

The first PRV for a rare pediatric disease was awarded in 2014 (Mease et al., 2024). A 2024 report by the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) showed that since the rare pediatric disease PRV program was established in 2012, there have been more than 550 rare disease pediatric designations and over 50 rare disease pediatric PRVs awarded (NORD, 2024). During the first few years of the program, Hwang et al. (2019) found that after the voucher program was implemented, drugs likely to be eligible for rare pediatric disease designation had a greater likelihood of progressing from Phase 1 to Phase 2 trials than ineligible rare disease drug products. However, no association between the launch of the program and changes in the rate of new pediatric drugs starting or completing clinical testing was found (Hwang et al., 2019). According to a 2020 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) study, drug sponsors indicated that PRVs were a factor in the decision-making process for drug development (GAO, 2020). A selection of researchers interviewed by GAO reported mixed views of the rare disease PRV program—some said that the program is a useful incentive, while others indicated that some sponsors received PRVs for products they would have likely developed anyway (GAO, 2020). Other stakeholders have also shared mixed views on the program, with some saying that PRVs have been important for small companies and others saying that PRVs are a source of additional revenue for companies that do not need the money to finance drug development (GAO, 2020). Since the last GAO report, the number of rare pediatric disease PRVs granted by FDA has more than doubled, suggesting an updated assessment of the program would be helpful (NORD, 2024).

Approvals of drugs with rare pediatric disease designation

Similar to ODD, rare pediatric disease designations are concentrated for a small number of diseases. Mease et al. (2024) found that of the 245 diseases that were granted rare pediatric disease designation between 2013 and 2022, 26 diseases accounted for 41 percent of all designations.

EXPEDITED REGULATORY PROGRAMS

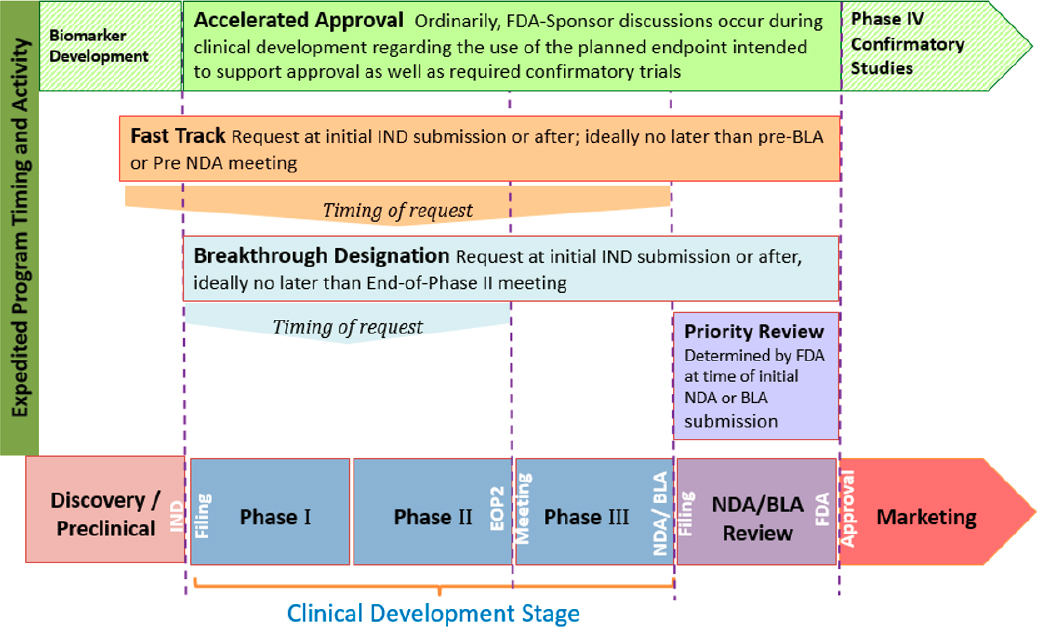

FDA has four general expedited programs to facilitate and expedite the development and review of certain new drugs and biological products: (1) accelerated approval, (2) fast track, (3) breakthrough therapy, and (4) priority review (see Figure 2-6). Additionally, CBER has a designation available for biologics—regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT)—and FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence has programs to expedite the review of medical products for oncologic indications. These programs are intended

NOTES: BLA = biologics license application; EOP2 = end of Phase 2; IND = investigational new drug; NDA = new drug application.

SOURCES: Presented to the Committee by Miranda Raggio, on November 6, 2023; created by Michael Lanthier; information derived from FDA, 2014b.

to facilitate and expedite the development and review of drugs that treat serious or life-threatening conditions (FDA, 2014b). FDA guidance for industry on expedited programs for serious conditions describes the eligibility criteria for expedited development and review and applies to both drugs and biologics under CDER and CBER (FDA, 2014b). Each program has its own criteria, timeline for request, and benefits, which are described in more depth below.

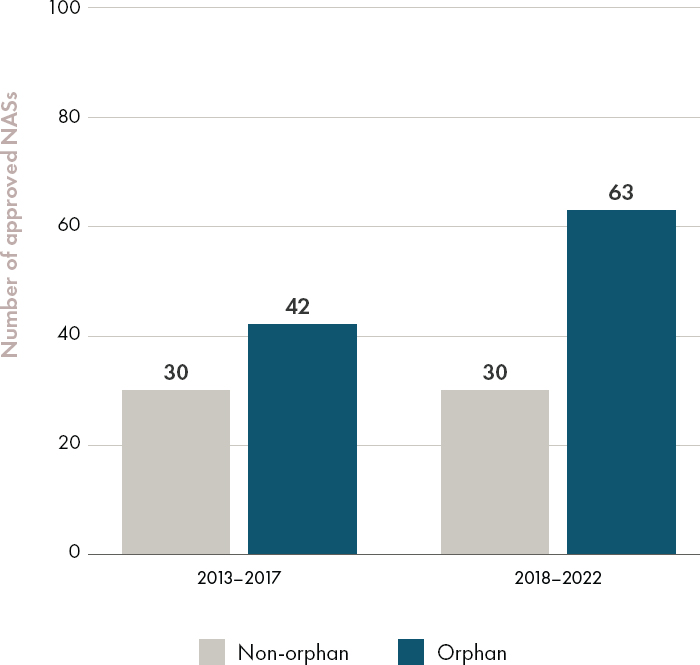

Expedited regulatory pathways may be used alone or in combination with ODD or with each other; the use of these programs, particularly in combination with ODD, has increased in recent years (see Figure 2-7). To be eligible for these expedited programs, a drug must be intended to treat a serious condition and generally must represent an improvement over existing therapies (e.g., must meet an “unmet need,” show a “meaningful advantage” over existing therapies, or provide “a significant improvement in safety or

NOTES: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NASs = new active substances.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

effectiveness”). Due to the seriousness of and the lack of available therapies for many rare diseases, products developed to treat rare diseases may be eligible for one or more of the expedited programs offered by FDA (FDA, 2014b).

Accelerated Approval

The accelerated approval pathway was established by FDA in 1992 in response to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic with the goal of bringing forward new therapies for patients who desperately needed treatment options. Today, the pathway is available for drugs that meet all of the following criteria (FDA, 2014b):

- The drug “treats a serious condition”; and

- The drug “generally provides a meaningful advantage over available therapies”; and

- The drug “demonstrates an effect on a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit, or on a clinical endpoint that can be measured earlier than irreversible morbidity or mortality that is reasonably likely to predict an effect on irreversible morbidity or mortality or other clinical benefit (i.e., an intermediate clinical endpoint).”

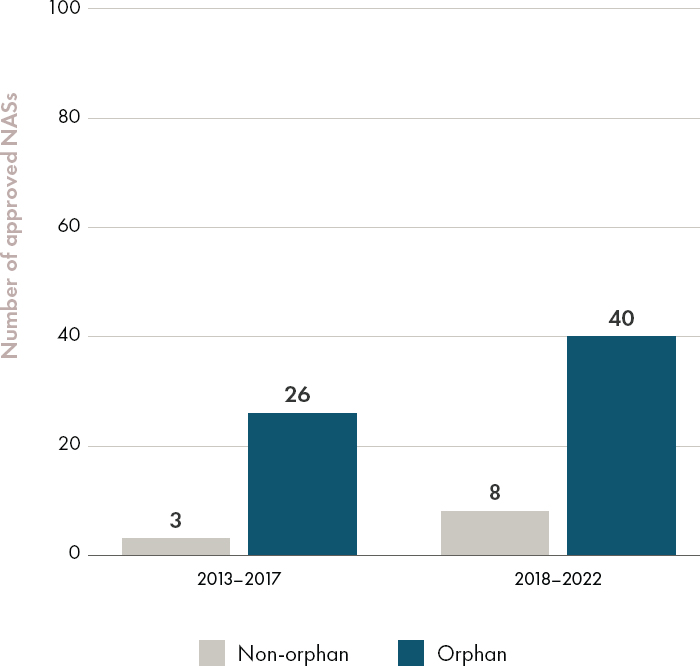

The pathway allows the use of a surrogate endpoint (e.g., a biomarker) or an intermediate clinical endpoint for accelerated approval—an approach viewed by some critics as subjecting patients to unnecessary risks (Kesselheim and Darrow, 2015; Redberg, 2015). Confirmatory trials are also required to verify and describe the clinical benefit (FDA, 2014b).27 In the early years of the accelerated approval program, the pathway was primarily used for drugs to treat human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and cancer. Between 2013 and 2022, 86 percent of all drugs approved through this pathway were orphan designated drug products (see Figure 2-8). The vast majority of drugs approved through this pathway between 2010 and 2020 have been for oncology indications; 85 percent of accelerated approval drugs treated cancers (Temkin and Trinh, 2021). Although the accelerated approval pathway is not used as frequently for non-oncology rare diseases as it is for rare types of cancers, if applied appropriately, it can be a beneficial tool for bringing safe and effective drugs to patients who suffer from serious and life-threatening conditions and for whom there are no meaningful alternative treatment options (Temkin and Trinh, 2021).

___________________

27 This sentence was edited after release of the prepublication version of the report to more accurately describe the accelerated approval process.

NOTES: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NASs = new active substances.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

As laid out in Chapter 1, the heterogeneity of rare diseases and conditions makes it difficult to identify and validate biomarkers for regulatory decision-making that are pertinent across the entire study population (Murray et al., 2023). To help fill this gap, efforts such as the Critical Path Institute’s Biomarker Data Repository, seek to advance ongoing research to advance new biomarkers for rare diseases and conditions (Critical Path Institute, n.d.).28 In 2022, Congress made several reforms to the accelerated approval program through the Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act

___________________

28 More information on the Critical Path Institute’s Biomarker Data Repository can be found at https://c-path.org/program/biomarker-data-repository (accessed June 26, 2024).

of 2022 to help promote transparency and more accountable use of the pathway (see Box 2-2).

Fast Track

FDA offers fast track designation for drugs that meet one of the following criteria:

BOX 2-2

Reforms and Future Direction of Accelerated Approval

The accelerated approval pathway recently came under scrutiny following a 2022 Office of Inspector General report, which documented that over one-third of drugs granted accelerated approval have incomplete confirmatory trials (OIG, 2022). The Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022 made several reforms to the accelerated approval program (Benjamin and Lythgoe, 2023). The first reform is focused on ensuring that confirmatory studies are conducted and submitted on time and providing new procedures for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to expedite withdrawal of approval if the sponsor fails to conduct the required studies. The second reform is aimed at improving transparency; sponsors will be required to submit progress reports on confirmatory studies every 180 days and these reports will be publicly available. Third, an Accelerated Approval Coordinating Council (AACC) will be formed to discuss issues related to the program and to implement necessary changes. Finally, if a sponsor is not required to conduct a post-approval study, FDA must publish a rationale for why a study is not appropriate or necessary.

In February 2024, Peter Marks, director of Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, stated that accelerated approval is “going to be the norm for a lot of . . . initial approvals of gene therapies” (Brennan, 2024). The accelerated approval program is based on the use of a surrogate endpoint, and Marks has stated that biomarker qualification is not a requirement for the pathway; that is, biomarkers used as surrogate endpoints do not need to undergo the FDA biomarker qualification process (Brennan, 2024). Since establishment in early 2023, the AACC has held discussions on policies related to accelerated approval, including the dissemination of policy across FDA to ensure consistent and appropriate application of accelerated approval (Benjamin and Lythgoe, 2023).

- Intended to treat a serious or life-threatening disease or condition, and nonclinical or clinical evidence demonstrate the potential to address unmet medical need;29 or

- Designated as a qualified infectious disease product30 (section 505E of the FD&C Act).

Impact

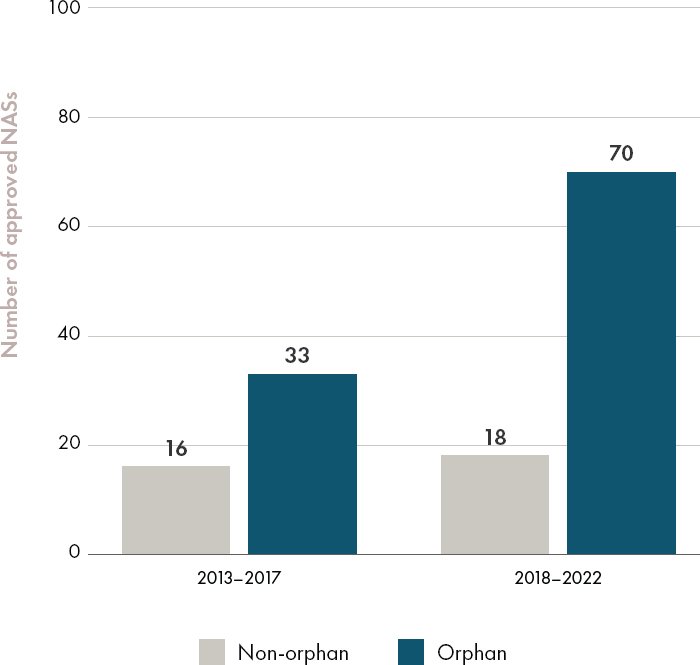

Many products developed for rare diseases meet the criteria for fast track designation—targeted at a serious or life-threatening condition and having the potential to fill an unmet medical need—at a higher rate than products developed for non-rare diseases. Using the fast track program may benefit sponsors of rare disease products by facilitating earlier and more frequent communication so that unique study issues can be discussed, and problems can be identified and addressed early in the process. Since the launch of fast track designation, it has been used primarily by orphan products, which accounted for over 50 percent of all designated products between 1998 and 2014 (Miller and Lanthier, 2016) and 64 percent of all designated products between 2013 and 2022 (see Figure 2-9).

Breakthrough Therapy

Breakthrough therapy designation is available for drugs that meet both of the following criteria:

- Intended to treat a serious or life-threatening disease or condition; and

- Preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement on a clinically significant endpoint(s) over available therapies (FDA, 2014b).

FDA guidance for industry, Expedited Programs for Serious Conditions (FDA, 2014b), goes into detail about the criteria that must be met for breakthrough therapy designation. FDA explains that “preliminary clinical evidence” means evidence generally from Phase 1 or Phase 2 clinical trials that is sufficient to indicate that the drug substantially improves upon available therapies but in most cases is not sufficient to establish safety and effectiveness for purposes of approval (FDA, 2014b). In general, to demonstrate a “substantial improvement,” preliminary clinical evidence should show a “clear advantage over available therapy.” The determination of whether there is substantial improvement over available therapy is

___________________

29 21 U.S.C. § 356b(1).

30 21 U.S.C. § 355f(g).

NOTES: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NASs = new active substances.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

a matter of judgment and depends on the size of the treatment effect and the importance of the effect to the treatment of the condition (FDA, 2014b). The “clinically significant endpoint” could be a measure of irreversible morbidity or mortality, specific symptoms that represent serious consequences of the disease, or an effect on a biomarker that strongly suggests an impact on a serious aspect of the disease (FDA, 2014b).

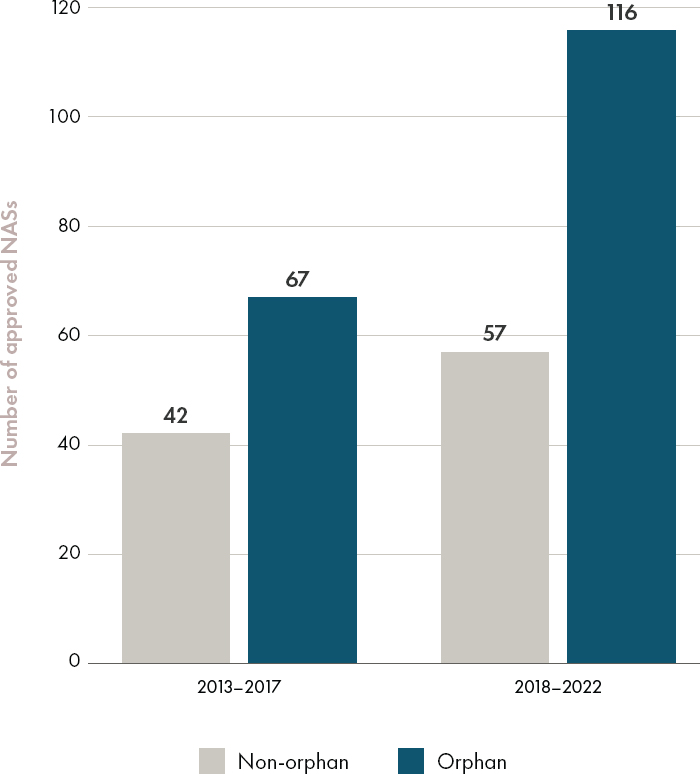

Due to the serious nature of rare diseases and the lack of available or adequate therapies, products aimed at rare diseases have received breakthrough therapy designation at a higher rate than products aimed

at common diseases (see Table 2-2 for data on non-oncology drugs and biologics). Between 2013 and 2022, orphan medical products accounted for 75 percent of all drug products that received the breakthrough therapy designation (see Figure 2-10). Moreover, between 2018 and 2022, over half (52 percent) of novel approved orphan drugs received the designation. Experience to date has shown that the breakthrough therapy designation can dramatically speed the development and approval for selected products, improving access to effective drugs for patients with difficult-to-treat conditions (Collins et al., 2023; Shea et al., 2016).

Priority Review

An application for a drug can receive a priority review designation if it meets one of the following criteria:

- It is an application (original or efficacy supplement) for a drug that treats a serious condition and, if approved, would provide a significant improvement in safety or effectiveness; or

- It is a supplement that proposes a labeling change pursuant to a report on a pediatric study under 505A; or

- It is an application for a drug that has been designated as a qualified infectious disease product; or

- It is an application or supplement for a drug submitted with a priority review voucher (see above for information about priority review vouchers).

| Category; n (% of designation requests) | Designation Granted | Designation Denied |

|---|---|---|

| Orphan product, no therapy available for disease; n=63 (26%) | 35 (56%) | 28 (44%) |

| Non-orphan product, therapy available for disease; n=80 (33%) | 18 (22.5%) | 62 (77.5%) |

| Orphan product, therapy available for disease; n=27 (11%) | 12 (44%) | 15 (56%) |

| Non-orphan product, no therapy available for disease; n=70 (29%) | 28 (40%) | 42 (60%) |

| Total; N=240 | 93 | 147 |

NOTE: CDER = Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

SOURCES: Presented to the Committee by Miranda Raggio, on November 6, 2023. Poddar et al., 2024. CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

NOTES: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NASs = new active substances.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

“Significant improvement in safety or effectiveness” can be demonstrated in several ways, including with evidence of increased effectiveness of treatment, prevention, or diagnosis; substantial reduction of a treatment-limiting adverse drug reaction; improved patient compliance that is expected to lead to improvement in serious outcomes; or evidence of safety and effectiveness in a new subpopulation (FDA, 2014b).

Between 2008 and 2021, 62.4 percent of all drugs receiving priority review designation were orphan drugs (Monge et al., 2022). Between 2013 and 2022, 65 percent of the drug products approved through priority review received orphan designation (see Figure 2-11). Priority review can

NOTES: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NASs = new active substances.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

help treatments reach market more quickly, which can be critical in rare disease where there may not be another treatment option.

Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy

In addition to the programs discussed above, there is one expedited program available only for specific biologics. The 21st Century Cures Act included a provision to establish the RMAT designation to enable a new expedited option for products that meet the following criteria:

- “The drug is a regenerative medicine therapy, which is defined as a cell therapy, therapeutic tissue engineering product, human cell and tissue product, or any combination product using such therapies or products, except for those that are regulated solely under Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act and part 1271 of Title 21, Code of Federal Regulations;31

- “The drug is intended to treat, modify, reverse, or cure a serious or life-threatening disease or condition; and

- “Preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug has the potential to address unmet medical needs for such disease or condition.” (FDA, 2023n)

RMAT designation is distinct from fast track and breakthrough therapy designation and has different requirements, but it includes the same benefits, such as early interactions with FDA to obtain advice on product development. In addition, there is potential for accelerated approval with post-approval requirements (FDA, 2019b). And during an open session of the committee, FDA staff reported that, as of December 31, 2022, of the 82 biologics that had received RMAT designation, 35 (43 percent) have been for orphan products (Raggio, 2023).

Oncology Center of Excellence Programs

FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE) was established in 2017 following its authorization by the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016. The OCE brings together experts from across the agency to conduct expedited review of medical products for oncologic indications (FDA, 2024l). Between 2013 and 2022, the majority of orphan designation applications approved by FDA were for anti-cancer and immunomodulator treatments (see Figure 2-5). During this time, FDA approved 2.5 times as many orphan applications for anti-cancer and immunomodulating treatments than for nonorphan treatments. Most of the orphan approvals during this time received an expedited review.

___________________

31 Human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissue-based products that are regulated solely under Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act and 21 CFR, part 1271 (aka “361 HCT/Ps”) do not undergo pre-market review. These products must meet the four criteria described in 21 CFR part 1271.10(a) (see https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-L/part-1271/subpart-A/section-1271.10) (accessed March 16, 2024).

Project Orbis

FDA’s OCE launched an international collaborative review program called Project Orbis in 2019. Applicants submitting marketing applications for products with great potential to address unmet medical needs can be considered for eligibility. Project Orbis partners can opt in or out of participating in the review of each application. The process allows for collaborative exchange of information and regulatory perspectives during the review process, while each country retains independent decision making. As of October 31, 2023, there were 81 Project Orbis applications that have resulted in product approval, with approximately one-third of these being new molecular entities in the United States (Donoghue, 2024).32 Project Orbis partners include representatives from Australia, Brazil, Canada, Israel, Singapore, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. As of late 2023, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (Japan’s regulatory body) became observers of the program but are not full partners in Project Orbis.

Applications in Project Orbis can be identified by the FDA review team or a sponsor can request inclusion (FDA, 2022h). Applications identified by FDA are recommended based on a combination of “breakthrough designation, impressive results, and unmet need” (FDA, 2022h). When a sponsor requests inclusion, the application is considered based on various criteria, and “high impact, clinically significant applications, should generally qualify for priority review because of improvement in safety/efficacy” (FDA, 2022h). The project is open to NDAs, BLAs, and supplemental applications for oncology indications. Sponsors are encouraged to submit marketing applications to all Project Orbis partners but are not required to do so. While review is collaborative and agencies share analysis with partners, sponsors must work with each regulatory agency to comply with regulatory requirements and timelines.

As an example of how Project Orbis works, its first review in 2019 involved FDA, Health Canada, and the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration. The three agencies collaboratively reviewed the application and identified all regulatory divergence; all three countries simultaneously approved the drug under their own accelerated approval programs. Each country used its own format for the drug label, although they exchanged labels to note any differences (FDA, 2022h). As a result of the collaborative process, the products—for a specific type of endometrial carcinoma—were approved. The approval came 3 months prior to the FDA goal date (FDA, 2019c). For rare disease patients and their families, gaining access to new treatments even a few months earlier can mean significantly improved health outcomes, reduced suffering, and a better quality of life.

___________________

32 The sentence has been modified after release of the prepublication version of the report to provide temporal context.

The overarching intent of Project Orbis is to leverage a global patient population and evolve toward uniform global standards (“global regulatory convergence”) for the evaluation of oncology-related orphan drugs and biologics. This is broadly applicable and appropriate for other rare diseases and aligns with the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). The framework of Project Orbis that informs the concurrent submission and collaborative review process will also help the community of potential Collaboration on Gene Therapies Global Pilot (CoGenT Global) stakeholders engage productively with the program by shaping their expectations (see Box 2-3).

BOX 2-3

Pilot Program: Collaboration on Gene Therapies Global Pilot

Over the past several decades, gene therapies have been developed for the treatment of rare diseases and conditions, including several products that received marketing authorization (Fox and Booth, 2024). Despite these successes, gene therapy for rare diseases has yet to meet the needs of most rare disease patients.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration/Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (FDA/CBER) is conducting a pilot program, the Collaboration on Gene Therapies Global (CoGenT Global), where proactive sharing of review experiences between multiple regulators could allow for better leveraging of global patient populations with rare diseases and could attract more sponsor interest in developing a product for a particular disease. It is expected that such exchanges may also lead to increased convergence among international regulatory authorities and encourage sponsors to develop their rare disease products internationally, ultimately increasing the availability of important treatments to patients in medical need. The pilot will be initiated in 2024, starting with the European Medicines Agency, and could be expanded to other international regulatory partners in the future (Anatol, 2024; Eglovitch, 2024; Lu and Abbott, 2024). According to Peter Marks, director of CBER, “if [FDA and EMA] can harmonize our requirements and pull forces to review these products, we can make it much more attractive for people to go into this rare disease area” (Eglovitch, 2024).

Specific and detailed information on CoGenT is still pending and much will depend on the early results of the ability of this pilot program to drive private capital investments in the development of gene therapies and to streamline the conduct of associated regulatory reviews. However, this platform could be even more useful by expanding its scope to include collaborations on issues like harmonization of rare disease registries across jurisdictions and setting of uniform minimum standards of real-world data quality, among other drug development tools.

Real-Time Oncology Review

The real-time oncology review (RTOR) was implemented by OCE in 2018 to “facilitate earlier submission of top-line results.” To be eligible for RTOR, a product must meet all of the following criteria (FDA, 2023m):

- Clinical evidence indicates that the drug demonstrates substantial improvement on a clinically relevant endpoint(s) over available therapies; and

- Clinical trial endpoints are easily interpreted; and

- No aspect of the submission is likely to require a longer review time.

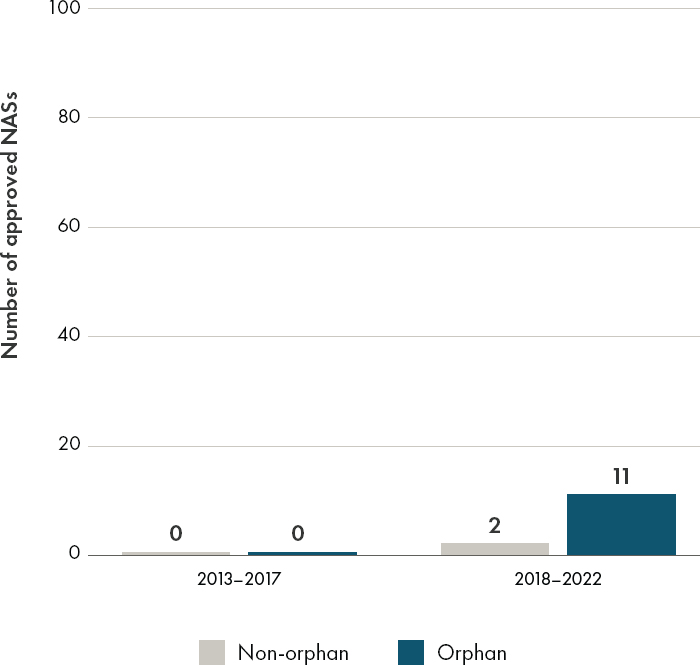

Though focused on cancers, RTOR has benefited rare diseases. Of the 10 new molecular entity (NME) product applications accepted by the initial pilot, 8 received orphan designation (Gao et al., 2022). Additionally, 11 of the 13 approvals through RTOR between 2013 and 2022 were for orphan products (see Figure 2-12).

One lesson that is relevant to rare diseases is that the program’s resource-intensive nature (e.g., submitting multiple application components at different time points as outlined in the RTOR operating procedures) means that it is key to have close coordination and alignment between the sponsors, which are often small biotech companies, and agency reviewers on expectations and submission timelines related to datasets, analysis, key claims in labels, and safety update reports among others. The RTOR program implementation has been associated with faster approval times (see Figure 2-13) although this may be confounded by the concurrent usage of other expedited programs such as breakthrough designation and priority review (Gao et al., 2022). The frequent interactions with FDA reviewers during the submission and review lifecycle due to the RTOR has meaningfully informed industry practice with respect to application preparation and FDA engagement (Kim, 2022). The abbreviated time from submission to approval means that this framework has considerable applicability to non-oncology rare diseases more broadly. Applying a similar framework may be beneficial for the advancement of rare disease drug development beyond rare cancers.

Orphan Drugs and Expedited Review

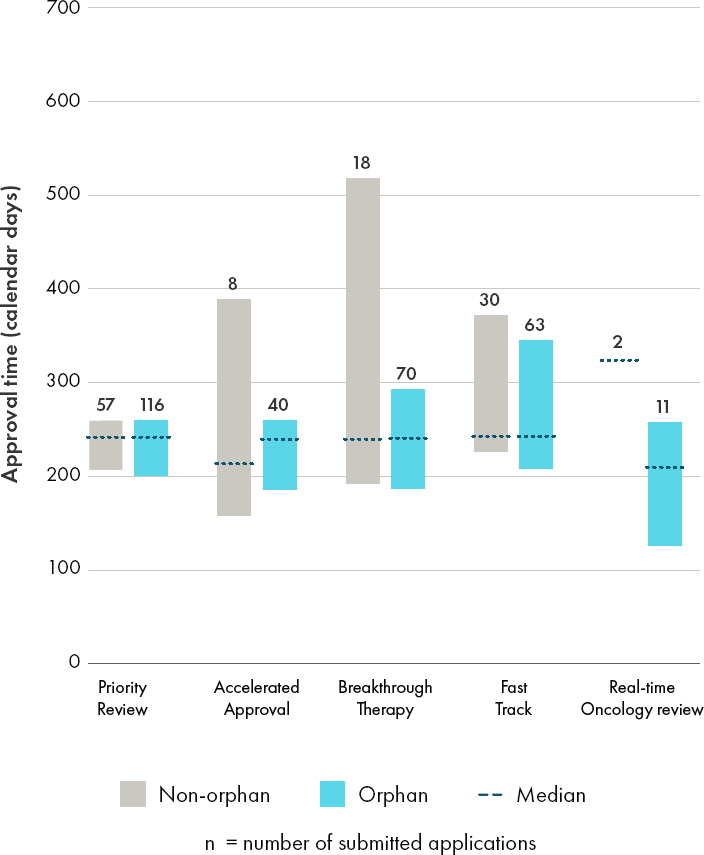

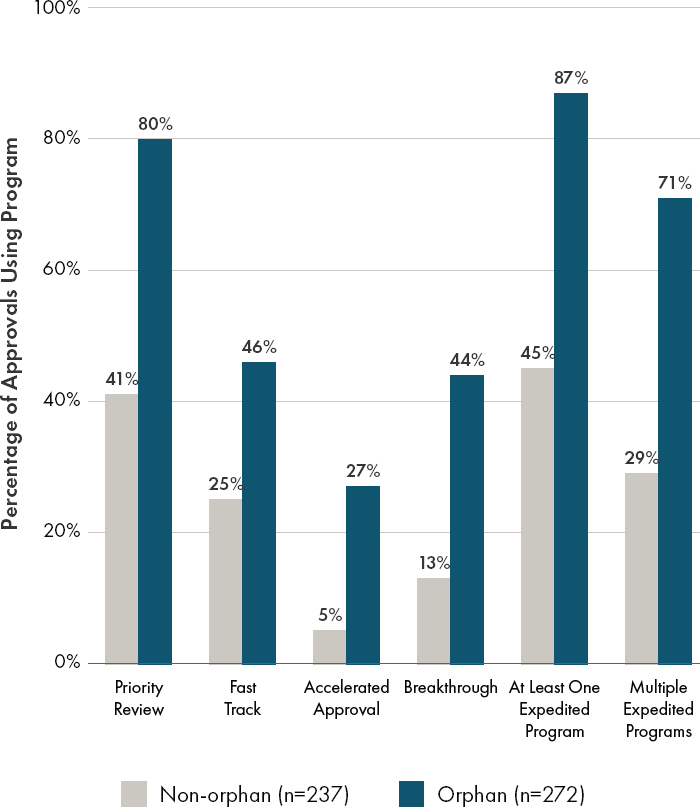

Orphan products use expedited programs more often than non-orphan products. Figure 2-14 shows the percentage of orphan drug approvals compared with non-orphan drug approvals for NMEs and new biologics in each of the four expedited development programs available to all drugs and

NOTES: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NASs = new active substances.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

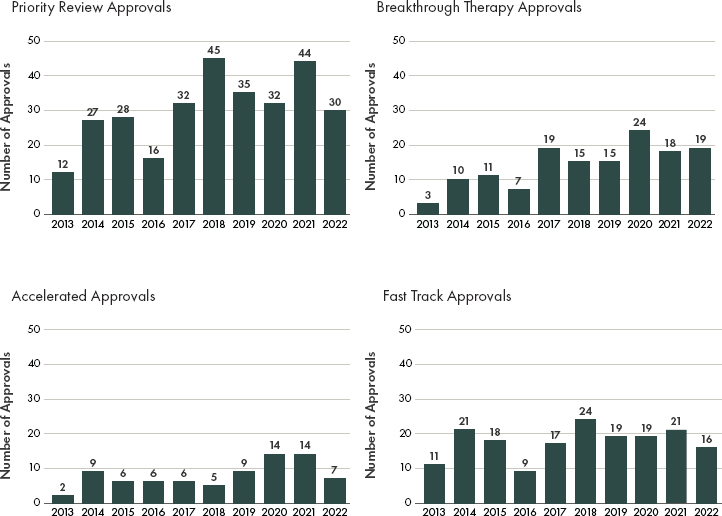

biologics. The number of approvals of NMEs and new biologics through each program varies; for example, in 2022, there were 30 approvals for priority review, 19 breakthrough therapy approvals, 7 accelerated approvals, and 16 fast track approvals (see Figure 2-15). Drugs and biologics may be eligible for more than one expedited program (see Figure 2-14). Median approval times for orphan and non-orphan products are generally comparable within a given expedited development pathway (see Figure 2-14). Expedited approval programs do not change FDA’s standards for approval. However, accelerated approval allows FDA to rely on a different evidence

NOTES: Box plot displays median approval time with 25–75% interquartile range. Range is not displayed when n < 3. FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

SOURCE: CIRS Data Analysis, 2024.

NOTES: CBER = Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; CDER = Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

SOURCES: Presented to the Committee by Miranda Raggio, on November 6, 2023; created by Michael Lanthier.

NOTES: CBER = Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; CDER = Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

SOURCES: Presented to the Committee by Miranda Raggio, on November 6, 2023; created by Michael Lanthier.

base. Surrogate endpoints or intermediate clinical endpoints can serve as the basis for accelerated approval with careful evaluation of the endpoints’ effect on clinical benefit (FDA, 2014b).

INCLUSION OF PEDIATRIC POPULATIONS

The majority of rare diseases affect the pediatric population (Wright et al., 2018). Evidence has shown there can be substantial differences in the way that children respond to drug treatment compared to adults (IOM, 2008). Thus, the inclusion of pediatric populations in clinical trials should be a core component for rare disease drug development. Epps et al. (2022) list the following challenges for rare pediatric disease drug development: “(1) garnering interest from sponsors, (2) small numbers of children affected by a particular disease, (3) difficulties with study design, (4) lack of definitive outcome measures and assessment tools, (5) the need for additional safeguards for children as a vulnerable population, and (6) logistical hurdles to completing trials, especially with the need for longer

term follow-up to establish safety and efficacy.” These challenges are common across all therapeutic areas, but are amplified for rare diseases and conditions.

Over the past several decades, a combination of legislation, regulatory action (see Table 2-3 for list of guidances on pediatric drug development), and the accumulation of scientific evidence has enabled what some have considered a to be a “revolutionary change” in pediatric drug development—a shift from considering pediatric populations as “therapeutic orphans” to a current state in which the number of drug products approved for use in children continues to increase (FDA, 2024m; Fung et al., 2021).

Two laws—the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA) of 2003 (FDA, 2024n), the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) of 2002 (NICHD, n.d.)—work together to address the need for pediatric drug development. Pediatric provisions in FDASIA further strengthened these laws (FDA, 2018b). BPCA provides incentives (additional marketing exclusivity) to encourage sponsors to carry out studies in pediatric populations, and PREA authorizes FDA to require pediatric studies for certain drugs and biological products (FDA, 2018b, n.d.-a; PhRMA, 2020; Sachs et al., 2012) (see Box 2-4).

Following enactment of BPCA and PREA, FDA has reported “significant progress in the number, timeliness, and successful completion of studies in pediatric populations” (FDA, n.d.-a). The number of pediatric labeling changes—updates to a drug product’s labeling to add information on safety, effectiveness, or dosing for children—has continued to increase

TABLE 2-3 FDA Guidance on Pediatric Drug Development

| Guidance | Source |

|---|---|

| Pediatric Drug Development: Regulatory Considerations — Complying With the Pediatric Research Equity Act and Qualifying for Pediatric Exclusivity Under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act | FDA (2023j) |

| Pediatric Drug Development Under the Pediatric Research Equity Act and the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act: Scientific Considerations | FDA (2023i) |

| ICH Pediatric Extrapolation: E11A | ICH (2022) |

| Ethical Considerations for Clinical Investigations of Medical Products Involving Children | FDA (2022d) |

| General Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Pediatric Studies of Drugs, Including Biological Products | FDA (2022g) |

| General Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Neonatal Studies for Drugs and Biological Products | FDA (2022f) |

| Considerations for Long-Term Clinical Neurodevelopmental Safety Studies in Neonatal Product Development | FDA (2023e) |

NOTE: FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

over time. Between 2010 and 2018, approximately one-third of the orphan drug indications approved by FDA were approved for use in children or targeted a pediatric disease (Kimmel et al., 2020). A more recent analysis showed that the percentage of orphan indications for rare pediatric diseases has continued to increase over time (Fung et al., 2021).

In 2020, PhRMA cited the following numbers:

- “Since 1998, there have been over 750 labeling changes reflecting pediatric information.

- “Since the reauthorization of BPCA and PREA in 2007, more than 680 pediatric studies have been completed under BPCA and PREA.

- “Over 250 drugs have been granted pediatric exclusivity under BPCA.

- “There are currently more than 2100 industry sponsored pediatric clinical trials underway, involving more than 1.2 million pediatric patients across a variety of therapeutic areas, including diseases

BOX 2-4

Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) and Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA)

BPCA

“BPCA exists to improve the safety and efficacy of drug use and dosage for children.

“The overarching goals of BPCA are to:

- “Encourage the pharmaceutical industry to perform pediatric studies to improve labeling for patented drug products used in children, by granting an additional 6 months of patent exclusivity

- “Authorize NIH, through Section 409I, to prioritize needs in various therapeutic areas and sponsor clinical trials of off-patent drug products that need further study in children, as well as training and other research that addresses knowledge gaps in pediatric therapeutics” (NICHD, n.d.).

PREA:

“PREA gives FDA the authority to require pediatric studies in certain drugs and biological products. Studies must use appropriate formulations for each age group. The goal of the studies is to obtain pediatric labeling for the product” (FDA, 2024n).

- where there is significant unmet need, such as infectious diseases, neurologic conditions, genetic disorders, and several forms of cancer” (PhRMA, 2020).

Notably, orphan designated drug products are generally exempted from PREA requirements. PREA states, “Unless the Secretary requires otherwise by regulation, this section does not apply to any drug for an indication for which orphan designation has been granted under section 526” (FDA, 2005). While the intent of this provision may have been to incentivize the development of drugs to treat rare diseases and conditions, patient groups, such as the Treatment Action Group and Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, have argued that the exemption has led to the opposite result—delays or complete lack of research on the safety and efficacy of rare disease drug products for pediatric populations (Treatment Action Group and Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, 2019).

PREA requires sponsors to submit an initial pediatric study plan (iPSP) “before the date on which the sponsor submits the required assessments or investigation and no later than either 60 days after the date of the end-of-Phase 2 meeting or such other time as agreed upon between FDA and the sponsor” (FDA, 2020b). The iPSP must include the following:

- “an outline of the pediatric study or studies that the sponsor plans to conduct (including, to the extent practicable, study objectives and design, age groups, relevant endpoints, and statistical approach);

- “any request for a deferral or waiver. . .if applicable, along with any supporting information; and

- “other information specified in the regulations promulgated under paragraph (7)”a

A sponsor should not submit a marketing application or supplement until FDA confirms agreement on the iPSP, and the total review period for iPSPs should not exceed 210 days. PREA provides an exemption from iPSP requirements for applications for drugs that have orphan designation. In 2017, PREA was amended by the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017, by including RACE for Children Act to lift the orphan exemption for rare pediatric cancers, requiring sponsors to submit iPSPs for these indications. This amendment has required that sponsors submit a planned approach for studying drugs in pediatric populations if they intend to apply for approval of adult cancer drugs (GAO, 2023).

__________________

a 21 U.S.C. § 355c(e)(2)(B).

The 2017 Research to Accelerate Cures and Equity (RACE) for Children Act33 amended PREA to remove the exemption for orphan designated drugs, but only for certain cancer drugs. A 2024 FDA briefing document to the Pediatric Oncology Subcommittee of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee stated that:

“Based upon the updated FDA analysis of initial pediatric study plans for molecularly targeted drugs and the results of the GAO audit, it appears that the RACE Act has contributed to an increase in the number of planned studies to test certain molecularly targeted drugs in pediatric patients with cancer. However, given the amount of time needed to design and conduct clinical trials evaluating new drugs for the treatment of pediatric cancers, it is too early to determine the extent to which implementation of the Food and Drug Reauthorization Act of 2017 (FDARA) provisions of PREA will advance the development of new treatments for pediatric cancers” (FDA, 2024g)

Closing the Gap

Despite legislative, regulatory, and scientific advances, meta-analysis has shown that off-label prescriptions for children accounted for up to 38 percent of all pediatric prescriptions between 2007 to 2017 (Allen et al., 2018). To this day, off-label drug use remains an issue for pediatric populations, particularly those living with rare diseases and conditions for which there is no available treatment on the market (Committee on Drugs et al., 2014). More is needed to meet the needs of children living with rare diseases and conditions.

In addition to measures taken by Congress to incentivize the inclusion of pediatric populations in rare disease drug development, FDA and NIH, in partnership with nongovernmental organizations—including patient and disease advocacy groups, academic clinical investigators, and biopharmaceutical companies—have an opportunity to better collaborate on approaches to include pediatric populations as early as possible in rare disease clinical trials.

During an open session held by the committee on February 7, 2024, senior representatives from CDER, CBER, and OCE all stated the agency’s view concerning the inclusion of pediatric participants early in clinical trials is “evolving.” This sentiment has been echoed by FDA in other venues. On FDA Rare Disease Day, February 27, 2023, Martha Donoghue, the associate director for pediatric oncology and rare cancers in OCE, stated that “over the past decade, this tendency to think about protecting pediatric patients from clinical trials has shifted to thinking that we can best protect

___________________

33 H.R.1231—RACE for Children Act—115th Congress (2017–2018).

pediatric patients with cancer through more timely and thoughtful conduct of pediatric clinical trials. In essence, to give them a chance to benefit through participation in clinical trials as soon as it is scientifically justified and feasible, with the ultimate goal of providing increased access to new, safe, and effective treatment that are approved for pediatric patients with cancer” (FDA, 2023g).

Dr. Nicole Verdun, director, Office of Therapeutic Products, CBER, FDA, stated publicly on March 8, 2024, “…traditionally, the thought has been that you should try things in adults before children…what I hear from patient communities is that we have diseases, especially in the rare disease space, that affect children from birth, and we want to prevent those conditions from happening. We do not want to wait to have to enroll a young child in a trial…we have to pivot a little in mindset and be comfortable with starting sometimes in areas where there is some uncertainty… it really depends on the program, but we are looking for ways to enroll pediatric patients earlier in the development process” (The Alliance for a Stronger FDA, 2024).

Such sentiments have been reiterated in other public meetings, including a 2024 Roundtable on Effective Inclusion of Children Early in Clinical Trials hosted by Leavitt Partners and the Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance, during which senior FDA leadership at the office, division, and center level discussed the need to pivot toward earlier inclusion of pediatric populations in clinical trials. The committee recognizes the need to focus on protecting children living with rare diseases and conditions through clinical trials, so they have access to safe and effective therapies.

RECOMMENDATION 2-1: Congressional action is needed to encourage and incentivize more studies that provide information about the use of rare disease drug products in pediatric populations. To that end, Congress should remove the Pediatric Research Equity Act orphan exemption and require an assessment of additional incentives needed to spur the development of drugs to treat rare diseases or conditions.34

Additionally, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the National Institutes of Health in partnership with nongovernmental organizations, including patient groups, clinical investigators, and biopharmaceutical companies, should work to provide clarity regarding the evolving regulatory policies and practices for the inclusion of pediatric populations as early as possible in rare disease clinical trials. Actions should include, but are not limited to the following:

___________________

34 This sentence was edited after release of the prepublication version of the report to clarify the intent of the recommendation.

- FDA should convene a series of meetings with relevant stakeholders and participate in relevant meetings convened by others to clarify what data are required to support the early inclusion of pediatric populations in clinical trials for rare diseases as well as other key considerations.

- Publish or revise guidance for industry on pediatric study plans for rare disease drug development programs.

STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT

As laid out in Chapter 1, rare disease drug development faces multiple challenges: lack of understanding of the underlying disease, a lack of defined endpoints, and limited patient populations.

FDA has recognized the need for its employees to supplement their knowledge, particularly for “new and emerging fields of science, pioneering technologies, and the increasing complexity of medical devices and pharmaceuticals” (FDA, 2024k). Drugs intended to treat rare diseases fall under each of these umbrellas.

FDA has a number of mechanisms in place to leverage the experience and expertise of external stakeholders, including public workshops on novel and evolving areas of development (e.g., disease-specific or method-based approaches), advisory committee meetings, and public comment on proposed regulations or guidances. Additionally, FDA can appoint special government employees, recruit qualified experts to serve on advisory committees, and collaborate with other organizations (FDA, 2016). The agency has used all of these mechanisms to support the review and approval of drugs to treat rare disease and conditions, though some of these approaches can be slow and onerous to implement.

FDASIA, signed into law in 2012, includes sections aimed at expanding the role of external stakeholders in FDA regulatory processes. Section 1137 directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “develop and implement strategies to solicit the views of patients during the medical product development process and consider the perspectives of patients during regulatory discussions.”35 This provision assists FDA in developing strategies for integrating the input of patients in regulatory decision-making.

Section 1138 of FDASIA “requires the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), acting through the Commissioner of Food and Drugs, review and modify as necessary, FDA’s communication plan to inform and educate health care practitioners and patients on the benefits and risks of medical products, with particular focus on underrepresented subpopulations, including racial subgroups” (FDA, 2013a). While these provisions are

___________________

35 21 U.S.C. 360bbb–8c.

complementary, they serve different purposes in aiding the agency better integrate the critical input of patients and ensuring adequate communication of information about drug development.

Patient Engagement

FDA has made important strides to engage people with lived experience throughout the regulatory review process. Guidance documents, patient focused drug development (PFDD) meeting summaries, direct interaction with patients, and other resources have helped to bridge the gaps among regulators, sponsors, and people with lived experience.