Automated Applications for Infrastructure Owner-Operator Fleets (2024)

Chapter: 9 Autonomous Transit

CHAPTER 9

Autonomous Transit

9.1 Description of Autonomous Transit

Public transit operations have the potential to be impacted by autonomous vehicle technologies. Private agencies and companies can see more short-term benefits, and due to the nature of private fleets, such as taxis, they are able to change operations to take advantage of the benefits. However, operating a transit vehicle is much more complex than operating a light-duty passenger vehicle. As an example, transit buses are much larger and need to operate in a wide variety of environments including being in proximity to vulnerable road users. In addition, transit operations are required to enable the safe transit of passengers, so new technologies that could entail liability need to be more carefully considered. As a result, it is likely that as autonomous vehicle capabilities are added to existing or included in the purchase of new transit vehicles, challenges, both technically and operationally, will likely entail the need for skilled human operators in the near future. Additionally, autonomous vehicle technologies may impact job duties requiring additional training (Martelaro et al. 2022).

The main application for autonomous transit is the use of shuttles for specific situations. The use of autonomous vehicles for other transit applications is more complex.

The Federal Transit Authority (FTA) developed a five-year strategic plan to research and advance safe and effective autonomous vehicle deployments, identify and find solutions for barriers to implementation, leverage technology from other sectors, demonstrate market-ready technology, and share knowledge (FTA n.d.).

Transit vehicles can be fully autonomous (Level 5 of the SAE Levels of Driving Automation standard, SAE J3016) or partially autonomous. To incorporate autonomous vehicle technologies into existing public transit systems, transit agencies need rigorous assessment and validation of autonomous vehicles in real-world scenarios and transit environments. As a result, it has been a common practice for many transit agencies to first deploy a driverless shuttle pilot program to assess how automated vehicle technology can enhance transit service and improve users’ satisfaction (Mahmoodi et al. 2021). Full autonomy, in fact, has primarily been limited to shuttles, which are low-speed vehicles typically used along a fixed route. Fully autonomous vehicles have been piloted in a number of areas, with a sample of these deployments described below.

SAE provides a common definition for autonomous vehicles. Those classified as Levels 3 and 4 in SAE J3016 are vehicles with some automated driving features but still require the presence of a human operator for safety and to take over driving the vehicle if needed (Feller 2021). Transit buses equipped with various automated features have been deployed. This includes features such as side or rear blind spot sensors which detect objects, lane departure warnings, collision detection to assess impact with vehicles or pedestrians, and overpass warnings. Transit

buses may also have features that assist with parking or docking, which may potentially save time and money. (Feller 2021).

Buses can be retrofitted with automation features. The various technologies include features such as the following:

- Imaging sensors such as cameras, radar, and lidar, which create a virtual model in real time of the area that surrounds the bus.

- Drive-by-wire systems which are used to automate control of features such as braking, steering, and throttle.

- Locating systems which include GPS and other inertial measurement units that determine location, speed, and changes in motion.

- Databases with needed information which may include high-definition maps.

- Computing systems that are able to capture data from the various sensors, maps, and other devices as well as provide directions to the drive-by-wire system through the use of artificial intelligence.

- Communications systems that can provide vehicle-to-everything (V2X) connections that interact with roadside sensors (i.e., traffic signals) as well as provide vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) connections with surrounding vehicles which may include applications like bus platooning.

9.2 Examples of Applications for Autonomous Transit

Information about how agencies have utilized autonomous transit systems was gathered from a review of the literature and a survey of agencies. The team also conducted an interview with one of the technology companies in the autonomous transit industry. The Orlando company has been providing autonomous technology and mobility services for alternative modes of transportation within communities, campuses, and municipalities. It currently uses geofenced areas with its vehicles at a controlled speed to enhance connectivity, relieve traffic congestion, and alleviate parking problems while improving the quality of life for the communities it serves.

Most of the information in this chapter centers on autonomous shuttle deployments. A summary of the applications found is presented below. Additional deployments are described in a summary assessment of the transit bus automation market by Cregger et al. (2023).

9.2.1 Responses from the Survey

A survey was conducted to gather information about the automated processes that IOOs have implemented or are planning to implement, as described in Chapter 3. Agencies were asked about the automated processes that they have used, including for transit. Around 16% (n = 5) of agencies that responded were using some type of autonomous shuttle. None were using autonomous buses. Another 75% (n = 24) indicated that they were planning to use or evaluate the use of autonomous shuttles in the next 3 to 5 years, and 84% (n = 27) had plans to use or evaluate the use of some type of autonomous transit bus. Nine percent (n = 3) of agencies indicated that they were not using or planning to use autonomous shuttles, and 16% (n = 5) indicated that they were not using or planning to use autonomous buses.

9.2.2 Summary of National Deployment Status

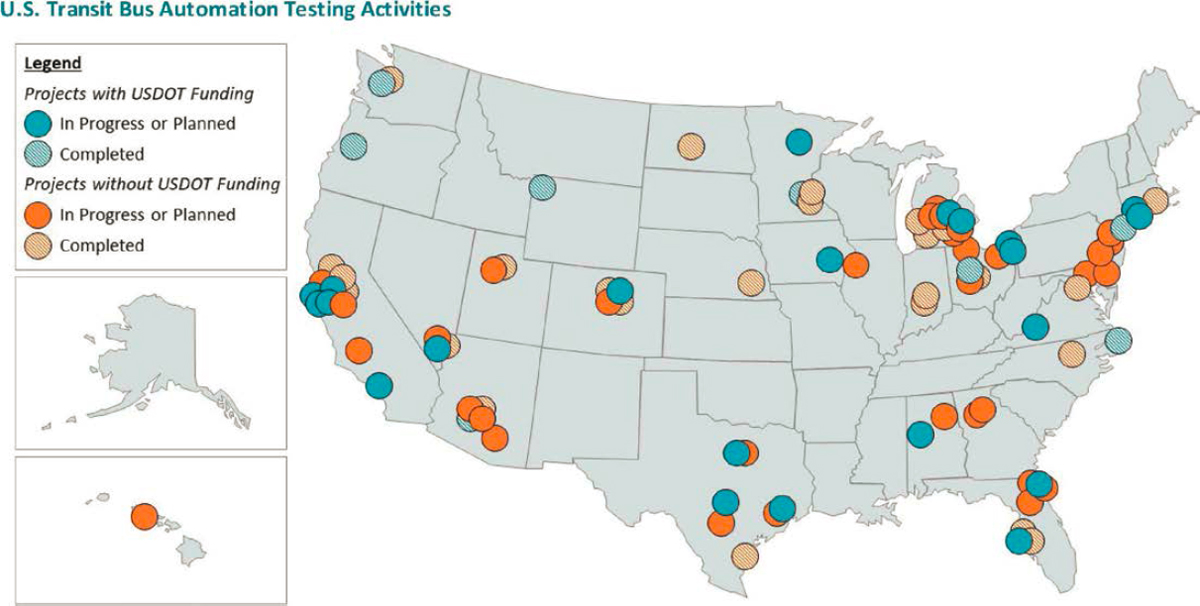

The FTA (2023) tracks many planned, in-operation, and completed automated transit bus test deployments. Known deployments as of July 2023 are shown in Figure 9-1.

Figure 9-1. Automated transit bus deployments.

9.2.3 Arizona

The Valley Metro Regional Public Transit Authority in Phoenix, Arizona, partnered with a vendor to pilot autonomous shuttles for a mobility on demand (MOD) service. A ride-sharing app was used by a group of participants in the pilot program to select trips within the service area. The agency also surveyed the perceptions and attitudes of 30 participants who used the autonomous service and eight who participated but did not use the service. Sixty-seven percent of respondents indicated that they liked the autonomous service better than a traditional ride choice. They also rated the wait time, travel time, convenience, and comfort of the automated service higher than those of a traditional ride choice (Stopher et al. 2021).

9.2.4 Georgia

Autonomous Shuttle

The city of Cumberland near Atlanta, Georgia, has undertaken an approach to introduce an autonomous shuttle service with no drivers. Under a pilot project, the shuttles will run within a 3-mi loop before fuller deployment. The project will involve the use of separate lanes for AVs (Green 2023).

9.2.5 Hawai’i

Autonomous Shuttle

The Hawai’i DOT, in conjunction with the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, piloted an all-electric, autonomous, ADA-compliant shuttle with a 14-passenger capacity. Due to Hawai’i’s autonomous vehicle testing law, the shuttle can be piloted on public roads. The shuttle is expected to be part of the Rainbow Shuttle service that operates on the campus of the University of Hawai’i

at Manoa. The all-electric shuttle is expected to save over 660 gallons of gas per year, which translates to an annual cost savings of approximately $3,133. Further, it is estimated that the shuttle will decrease carbon dioxide emissions by over 13,000 lb per year (AASHTO 2023).

9.2.6 Florida

Florida has been at the forefront of autonomous shuttle pilot programs. Several are described below.

Autonomous Shuttle

The Jacksonville Transportation Authority worked with a vendor to launch autonomous transit vehicles with no attendant on board to transport COVID-19 test samples for the Mayo Clinic. Transport of samples by autonomous shuttles, ordinarily done by Mayo Clinic staff, allowed them to shift time towards other important tasks. Additionally, the use of the automated shuttles to move samples was a safer alternative for staff since they had less interaction and therefore exposure to the virus. Through this application, the clinic safely moves thousands of COVID-19 test samples from a drive-thru site to the processing laboratory.

Move Nona is another application of autonomous shuttles, which created a network of autonomous shuttles to connect residential, commercial, retail, recreational, and medical services. This resulted in the longest and largest network of autonomous shuttles in the country for a single location. Move Nona includes eight shuttles over five routes which connect several destinations within the 17 square mi Lake Nona, Florida community.

The Hillsborough Area Regional Transit Authority deployed a self-driving shuttle between the Marion Street transitway and the scenic Tampa Riverwalk which are located in downtown Tampa, Florida. The HART SMART AV program (see Figure 9-2) is funded by FDOT and is the first fully electric automated vehicle program that has been piloted within the Tampa Bay region.

The Miami-Dade County Department of Transportation and Public Works also partnered with a vendor to operate an autonomous shuttle at Zoo Miami that transports passengers to and from the parking lot (see Figure 9-3). The shuttle started operating in September 2022 and is an example of a first/last mile application (Miami-Dade County 2022).

Orlando, Florida, is piloting a self-driving eight-passenger shuttle that will traverse a 1 mi loop in the downtown area. The objective of the pilot program is to gather data that will guide future transit strategies. Like the other autonomous shuttle deployments in Florida, the shuttle is operated by an Orlando company (Transport Topics 2023).

Figure 9-2. Tampa HART SMART AV program.

Figure 9-3. Zoo Miami shuttle.

9.2.7 Iowa

Automated Transit

The University of Iowa (Iowa City, Iowa) upfitted an ADS-equipped small transit bus with additional sensors. The bus was tested along a 47 mi loop from Iowa City to several rural areas and small towns starting in 2021. The bus used a phased approach to incorporate different levels of autonomy (Cregger et al. 2023).

9.2.8 New Mexico

Automated Transit

San Jose, New Mexico, is planning to connect the San Jose Mineta International Airport and Diridon station using robotic shuttles. The project, which is expected to cost $500 million, is planned to be underway by 2028. The city is working with a local startup to implement driverless shuttles that can carry up to four passengers The project was deemed necessary because no viable public transportation options were available (Greschler 2023).

9.2.9 North Carolina

Autonomous Shuttle

NCDOT piloted an autonomous shuttle in Bond Park in Cary, North Carolina, that provided free public transportation to four stops, including community centers and shelters. The demonstration was part of the NCDOT Connected Autonomous Shuttle Support Innovation program, which piloted three other shuttle demonstrations, including an autonomous shuttle at Wright Brothers National Memorial in 2021 (Davidson 2023). The Bond Park project collected data that were displayed publicly and included information such as the number of passengers each day, the number of times the wheelchair ramp was deployed, hours of operation, and battery status. The shuttle was able to travel up to 12 mph. The pilot project also included an evaluation of the factors that kept the shuttle out of service during its first 6 weeks of operation. It was found that inclement weather was the cause 37% of the time, insufficient battery 28% of the time, and staffing issues 26% of the time. Blockage of the route only impacted service 1% of the time (Davidson 2023).

9.2.10 Ohio

Autonomous Shuttle

The city of Columbus, Ohio, evaluated a self-driving shuttle along a 1.5 mi route in the downtown area. The route was chosen as a first/last mile solution (Smart Columbus 2022).

9.2.11 Texas

Autonomous Shuttle

Texas A&M Transportation Institute introduced an autonomous, self-driving electric vehicle (EV) that navigates around the Texas A&M campus. The vehicle can carry 11 passengers and is equipped with optimized movement and safety features. The system is managed using interpretive, deep-learning software capable of adapting to real-time dynamic conditions. This vehicle does not include a traditional steering wheel or brake pedal, but a safety driver is always present (TTI 2019).

9.2.12 Virginia

Autonomous Shuttle

Fairfax County, Virginia, is piloting an autonomous electric shuttle as a first/last mile solution. The shuttle is programmed to follow a prerecorded path relying on GPS, odometry, and sensors such as laser scanners and cameras to constantly scan the area around the vehicle and navigate the environment. The system is thus able to detect obstacles such as vehicles, cyclists, or pedestrians and react accordingly. The shuttle can operate at 10 mph (Fairfax County, Virginia 2023).

9.2.13 Wyoming

Autonomous Shuttle

Yellowstone National Park (NP) developed a partnership with an Orlando vendor to deploy automated shuttles which was a first within a national park. The goal of the deployment was to assess the feasibility and long-term sustainability of autonomous shuttles in this type of setting. The information gained from the pilot provided information to make long-term management decisions for Yellowstone NP and other agencies interested in considering autonomous shuttles in national parks. The shuttles transport visitors between the Canyon Village campground, visitor services facilities, and adjoining lodge areas (NPS 2023). A vehicle used in the pilot program is shown in Figure 9-4.

Figure 9-4. Autonomous shuttles in Yellowstone National Park.

9.3 Summary of Applications for Autonomous Transit

Nine states were identified as using some type of automated transit buses. Most were piloting an autonomous shuttle.

9.3.1 Advantages

The advantages of autonomous transit are difficult to assess because most are based on expectations of what future autonomous transit systems will look like. The following are high-level estimates of what those advantages are likely to be:

- Improved access to transit with first/last mile autonomous shuttles,

- Reduced fuel costs due to the use of all-electric vehicles,

- Increased vehicle utilization and frequency (Othman 2020),

- Increased access for people with reduced mobility,

- Increased safety for riders and other road users,

- Reduced driver stress and fatigue (Othman 2020), and

- Reduced labor costs [Around 80% of the cost of operating transit is labor (Burger 2021)].

9.3.2 Disadvantages

The following are high-level estimates of what the disadvantages of autonomous transit are likely to be:

- Lengthy timeframes to obtain necessary approvals due to regulatory frameworks and permitting processes.

- High implementation costs (Although cost estimates are not readily available, AVs are expected to be more costly than traditional transit vehicles).

- Low turnover of existing transit fleet vehicles, which hampers adoption.

- Requirement of different workforce skills to operate and maintain automated and autonomous transit vehicles.

9.3.3 Costs

Most of the sources consulted did not provide specific estimates of cost. Many transit agencies have received U.S. DOT funding to pilot or implement their automated vehicle programs. Cregger et al. (2023) conducted a market assessment of automated and autonomous transit vehicles for the FTA and found that cost and price estimates are variable due to changing technology and are therefore largely unavailable.

9.3.4 Status of Automation-Assisted Shuttles

Fully autonomous shuttles are market-ready and have been piloted in a number of locations. However, these vehicles are produced at scale, and some models may not comply with federal requirements (Cregger et al. 2023). Automated technologies are being retrofitted to existing buses and are becoming available in new transit buses. Cregger et al. (2023) note that timing estimates for the commercialization of autonomous transit vehicles are not available, but the authors provide an in-depth summary of the status of automated transit buses along with challenges and market barriers.