Impacts of National Science Foundation Engineering Research Support on Society (2024)

Chapter: 5 Communicating Engineering Impacts on Society to Diverse Audiences

5

Communicating Engineering Impacts on Society to Diverse Audiences

This last chapter of the report addresses the final element of the statement of task: providing guidance on how to inform diverse audiences about engineering’s impacts on society. The text examines the considerations that go into communicating impacts and what research tells us about this topic and enumerates the many audiences there are for such communication. It sets forth the committee’s approach to developing example outreach materials, presents summaries of those materials, and closes with the committee’s conclusions and recommendations regarding communication issues.

The chapter is not intended to be a literature review or a comprehensive examination and is instead an overview of salient information that factored into the committee’s thinking. Appendix B contains a more detailed discussion of the literature related to science and engineering communications as part of the documentation accompanying the examples of engineering impacts on society outreach materials.

THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNICATING ENGINEERING’S IMPACTS ON SOCIETY

Any effort to convey the extraordinary impacts that engineering has had on society encounters an immediate problem: most Americans, including most K–12 students and their teachers, have very little understanding of what engineers do or how their work affects everyday life. A survey conducted in Canada ranked engineering second to last in familiarity among a list of professions, behind nurses, doctors, dentists, electricians, lawyers, and accountants and ahead only of architects (Innovative Research Group, 2017). They were roughly in the middle of these professions in terms of favorability, trust, and respect, though those who were more familiar with engineering gave the profession higher rankings than did other respondents. In this survey, engineers were ranked high in their levels of expertise but low in creating social value or being involved in communities.

Polls conducted in the United States have similarly shown that the public109 has limited understanding of engineering’s role in improving quality of life. In a 2004 survey, engineers were ranked far behind scientists in terms of saving lives, being sensitive to societal concerns, and caring about the community (Baranowski and Delorey, 2007). K–12 students in particular tend to have a relatively narrow understanding of engineering. They may know that engineers

___________________

109 While the committee uses the collective term “public” here and elsewhere in the report, it acknowledges that there are many “publics” that have different communications needs and different messaging preferences. These are addressed later in the chapter.

design and build things, but they usually cite the mechanical or structural aspects of engineering and overlook the broad range of activities and domains in which engineers are engaged (NAE, 2008). Even many of the students who plan to become engineers have a limited sense of the tasks engineers that perform or the areas in which they work.

Confusion about the differences between science and engineering contributes to inaccuracies in public perceptions. Many of the great technological accomplishments of the 20th century, such as computers, spacecraft, and health technologies, are largely products of engineering but are often described as scientific advances. To take three well-known examples, the Manhattan Project, the Apollo Project, and the Human Genome Project, each succeeded because of the engineering work that brought them to fruition as well as the scientific advances that made it possible to conceive of these projects.

Similarly, almost every object that we use daily has been created or refined by engineering, though the contributions of engineering are often unknown or underappreciated. Scientific findings may or may not have played a role in an engineer’s work, and the engineers who designed or modified an object certainly drew on their scientific understanding of the world in carrying out their tasks. But engineering delivered that object into our hands.

The lack of understanding or appreciation for engineering has several negative consequences. Underestimating the value that engineering provides can lead to underfunding of engineering research and education by legislators and government agencies—not only within NSF but also at more mission-oriented federal agencies (the historical underfunding of renewable energy research is an example) and at the state and local level. K–12 students who know relatively little about engineering are unlikely to pursue engineering in college or as a career, even though the profession offers well-paid and fulfilling jobs. Lack of knowledge about engineering can lead to uninformed decisions in the marketplace, which can result in substandard goods and services. In a world facing complex problems that demand creative and technologically sophisticated responses, engineering must be at the forefront of developing solutions.

Importantly, though, these observations do not mean that simply supplying audiences with information on engineering, engineers, or the impacts of engineering on society will address the underlying problems identified. The National Academies report Communicating Science Effectively: A Research Agenda (NASEM, 2017) offered insights on the weaknesses inherent in this viewpoint, known as the “deficit model”. It observed that effective communication must convey complexity and nuance in a way that is useful and understandable to its intended audience, acknowledging that facts can be interpreted in multiple ways. Technical communication often involves intermediaries like organizations and media, who influence how the information is received based on their credibility, the audience’s existing knowledge, and their beliefs. Therefore, simply providing more or clearer information is not always sufficient to achieve communication goals.

Further, assuming that better-crafted messages or more information alone will lead to desired actions overlooks the role of values, socioeconomic conditions, and other considerations in decision-making. People do not base decisions solely on the information presented; thus, effective communication needs to help audiences understand relevant facts and their implications while recognizing the influence of other factors. A well-crafted message for one audience may not suit another, as effective communication requires engaging with different audiences in varying contexts and considering their specific knowledge, needs, and beliefs.

There are myriad impacts of NSF-funded engineering research and education that the public does not associate directly with engineering. While the committee acknowledges that raising awareness of these impacts will not necessarily prompt interest in engineering nor resolve all systemic barriers to higher education access to the field, it may, in some cases, inspire and motivate students to consider an engineering career path by providing a better understanding of engineering and showcasing role models from similar backgrounds. The following sections illustrate how narratives that, by definition, go beyond just factual information, can help to meaningfully connect decision-relevant pieces of information to core audiences to maximize engagement.

CONSIDERATIONS IN COMMUNICATING ENGINEERING IMPACTS

Research on communicating the impacts of engineering to diverse audiences is relatively scarce, but the work that has been done provided insights to the committee to use in formulating their advice to NSF.

Research Conducted for Changing the Conversation

In 2008, the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) publication Changing the Conversation: Messages for Improving Public Understanding of Engineering, known as the CTC report, presented the results of a research-based effort to develop new and more effective ways of communicating about engineering (NAE, 2008). Using qualitative and quantitative research conducted by the communications and market research firms BBMG, Global Strategy Group, and Harris Interactive, the study began by developing a positioning statement to guide future outreach activities by the engineering community:

No profession unleashes the spirit of innovation like engineering. From research to real-world applications, engineers constantly discover how to improve our lives by creating bold new solutions that connect science to life in unexpected, forward-thinking ways. Few professions turn so many ideas into so many realities. Few have such a direct and positive effect on people’s everyday lives. We are counting on engineers and their imaginations to help us meet the needs of the 21st century (NAE, 2008; p. 5).

This positioning statement was considered to be too complicated and lengthy to serve as the basis for a major communications campaign. Instead, the statement was used to develop a small number of messages designed to present an effective case for the importance of engineering and the value of an engineering education, and these messages were then tested and refined through focus groups and surveys. The four messages that emerged from this process were:

- Engineers make a world of difference. From new farming equipment and safer drinking water to electric cars and faster microchips, engineers use their knowledge to improve people’s lives in meaningful ways.

- Engineers are creative problem-solvers. They have a vision for how something should work and are dedicated to making it better, faster, or more efficient.

- Engineers help shape the future. They use the latest science, tools, and technology to bring ideas to life.

- Engineering is essential to our health, happiness, and safety. From the grandest skyscrapers to microscopic medical devices, it is impossible to imagine life without engineering.

These messages cast engineering as inherently creative and concerned with human welfare as well as an emotionally satisfying career. Adults and teens of both genders rated “Engineers make a world of difference” as the most appealing message. Among teens, boys found this message as appealing as “Engineers are creative problem solvers.” For girls, the second-favorite message was “Engineering is essential to our health, happiness, and safety.” Girls ages 16 to 17 in the African American sample and all girls in the Hispanic sample found this second message significantly more appealing than did the boys in those groups.

A fifth message was also tested:

- Engineers connect science to the real world. They collaborate with scientists and other specialists (such as animators, architects, or chemists) to turn bold new ideas into reality.

This message was given the fewest votes for “very appealing” among all groups and was the least “personally relevant” for all groups except for African American adults. Messaging about engineering has often emphasized the strong connections between engineering and the need for mathematical and science skills. But by downplaying such aspects of engineering as creativity, teamwork, and communication, messages solely about the scientific and mathematical basis of engineering can imply that it is suited just for a small subset of people with particular interests and characteristics.

The study also developed seven “taglines,” short phrases that capture some aspect of the positioning statement in a succinct and memorable way:

- Turning ideas into reality

- Because dreams need doing

- Designed to work wonders

- Life takes engineering

- The power to do

- Bolder by design

- Behind the next big thing

When survey respondents were asked to rank these taglines, the most successful among all groups was “Turning dreams into reality,” though a greater percentage of boys than girls favored it. “Because dreams need doing” was especially popular among teenagers and was liked equally well by girls and boys. Among African American teens, the second most appealing tagline was “Designed to work wonders.” The second favorite choice of Hispanic adults and teens was “Because dreams need doing.”

The NAE committee that produced Changing the Conversation recommended that the engineering community use the positioning statement, messages, and taglines in the report to carry out coordinated and consistent communication to a variety of audiences, including school children, their parents, teachers, and counselors, about the role, importance, and career potential of engineering. It also observed that the messages and taglines should be embedded within a

larger strategic framework—a communications campaign driven by a strong brand position communicated in a variety of ways, delivered by a variety of messengers, and supported by dedicated resources. The committee recommended strategies and tools that the engineering community could use to conduct more effective outreach. In addition, it noted that the impacts of communications should be measured so that outreach efforts can be continually improved.

Building on Changing the Conversation

The 2013 NAE report Messaging for Engineering: From Research to Action reviewed the progress that had been made in implementing the CTC messages and taglines and provided an action plan for each major stakeholder in the engineering community (NAE, 2013). It noted that many organizations had either directly used or adapted the messages and related taglines from Changing the Conversation. For example, the Society of Women Engineers reworked all its print and web-based messaging to align with the CTC recommendations, and the Engineer Your Life website, which sought to encourage college-bound girls to pursue engineering, used the CTC and similar messages. The NAE linked the CTC messages and taglines to its Grand Challenges for Engineering and developed tools to help disseminate the CTC messages. Large and well-known companies such as DuPont, Exxon Mobil, and Lockheed Martin generated advertising or recruiting materials that reflected the CTC messages. While many of these efforts are no longer active, they succeeded in spreading the CTC messages and taglines widely within the engineering community (Vest, 2011).

In its proposed action plan, Messaging for Engineering outlined basic steps that all segments of the engineering community could take to change the conversation around engineering as well as specific steps for individual segments of the community (NAE, 2013). For example, it urged that communications make explicit use of the words “engineer” and “engineering” and use the CTC messages and taglines with a view of the engineering profession as a whole. It also noted the importance of reaching out to girls, African Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians, given their continued underrepresentation in the field. It urged that the impact of using or adapting the CTC messages be assessed in terms of not just inputs, such as the number of visits to a website, but also outputs, including changes in attitudes or behavior that result from the messaging.

In a paper that came out the same year, Betty Shanahan, who was a member of the committee that produced Messaging for Engineering, and two colleagues urged for engineers to use methods and tools for outreach projects that they routinely use in their technical projects but do not typically apply to outreach projects, e.g., research, training, adoption of best practices, and awareness of user needs and culture (Bogue et al., 2013). They observed that engineering professional societies invest an estimated $400 million annually in outreach messaging, activities, and materials to increase the number of students who study engineering in college, particularly among women and members of minority groups. But “this impressive outlay of resources generates a dismal return when one considers the primary outcomes metric: how many students chose to enter, and then persist in, engineering” (p. 12). Reports on which kinds of activities and practices work best, research into messaging and its effects among different groups, and meaningful evaluation of assessment results can all improve the return on investment, they wrote. “Assessment-based practice is the core of successful event planning and delivery in outreach, just as it is in every engineer’s career success” (p. 15).

Branding

Both Changing the Conversation and Messaging for Engineering explicitly sought to change the branding of engineering (NAE, 2008, 2013). As the two reports explain, a brand is an association of specific traits in a person’s mind that induces particular ideas and behaviors. Changing a brand therefore can change how a person thinks about and responds to information about a subject.

In a 2011 article in The Bridge, Mitch Baranowski discussed some of the issues associated with branding in the context specifically of engineering (Baranowski, 2011). Audiences are co-owners of brands, he pointed out, as they bring their own pre-existing frames to communications. These frames are built not just on fact but also on narratives. According to Baranowski, “Humans are emotional creatures who don’t necessarily respond to facts. We respond to stories. We respond to seeing people like us in situations we want to be in. We are aspirational, and this must be taken into account in creative communications. The best brands close the gap between the strategic and the creative, between the rational and irrational” (p. 15).

Brands are built from the inside out, Baranowski observed. Thus, a brand needs to be sold internally before it can be effectively sold externally. Brands should also be strategic drivers, he said, so that the idea behind a brand drives not just current actions based on past planning but ongoing planning for future actions.

Brands need to work across all media types. “From a design perspective, this means brand unity, consistency, developing and following brand guidelines, and internally monitoring how well the guidelines are followed,” Baranowski wrote (Baranowski, 2011, p.14). Also, brand ambassadors can be particularly effective in representing a brand to a target audience, but this representation needs to be coherent and consistent. The engineering community is decentralized and varied, encompassing engineering schools, professional societies, companies, the public sector, science and technology centers, and some K–12 schools and programs. Each of these parts of the community has unique goals, capabilities, and parochial interests. In addition, engineers do not agree on a single definition of engineering, or they may focus on their own field rather than engineering in general. These factors create obvious challenges to the coordinated and consistent delivery of messages.

The messages of a branding campaign need to align with the experiences of those at whom the campaign is directed, Baranowski said. For example, undergraduate engineering programs do not necessarily align with the messages of the CTC campaign. An even greater risk is known as the “promise gap,” or the “bait-and-switch” (Lachney and Nieusma, 2015), where a communications campaign promises something that subsequent experiences do not deliver. If students decide to study engineering because they have heard that it is a creative profession in which they can solve societal problems but then undergo years of classes in which they mostly work on problem sets, they may feel that they have been misled and could convey that disillusionment to others.

In the context of engineering, Baranowski asked several pertinent questions. To the extent that a brand is associated with a single word, which word does engineering own? What one thing sets engineering apart from other professions? In what way is engineering in a leadership position among professions? How can stories be built around the brand of engineering? Who are the best messengers or ambassadors for engineering? What images should they use, and how should their messages differ for different audience?

Framing

Framing is defined as “casting information in a certain light to influence what people think, believe, or do” (NASEM, 2017; p. 36). When we are provided with information, we use our cognitive schema110 to assess it and act on it. Information that is consistent with our schema tends to be accepted and assimilated, which in turn reinforces it. Information that does not fit may be downplayed or ignored.

Framing is a process that communicators use to position and present information in a way that takes account of how people interpret it. For instance, a writer scripting a movie might present an engineer as intelligent, industrious, socially disengaged, or beholden to special interests, depending on the frame the writer wishes to invoke. Changing widespread impressions and ideas about engineering therefore requires framing communications in such a way that existing frames are modified to become more realistic and more constructive.

Framing can reorient a person’s thinking about an issue, but framing that seeks to change ideas and behaviors must take into account their existing ways of processing information. This requires identifying and analyzing those ways of thinking, including how they change over time (Chong and Druckman, 2007).

Scheufele (2014) summarizes the issues and goals surrounding framing in science communication:

The challenge for science communication, therefore, is not to debate whether we should find better frames with which we can present science to the public …. Instead, we should focus on what types of frames allow us to present science in a way that opens two-way communication channels with audiences that science typically does not connect with, by offering presentations of science in mediated and online settings that resonate with their existing cognitive schemas, and present issues in a way that “resonates” and therefore is accessible to different groups of nonscientific audiences, regardless of their prior scientific training or interest. (p. 13589)

Storytelling

As Baranowski observed in his analysis of branding, people tend to respond to narratives more strongly than they respond to facts, an observation strongly supported by research (Baranowski, 2011). For nonexpert audiences, narratives are easier to comprehend than are traditional scientific explanations. Stories feature a cause-and-effect relationship among events that occur to characters over a period of time. In this way, narratives describe specific situations within the context of more general truths. Explanations in science and engineering, in contrast, tend to move from abstract truths toward specific instances that adhere to those truths. As Dahlstrom observes, “[i]n essence, the utilization of logical-scientific information111 follows deductive reasoning, whereas the utilization of narrative information follows inductive reasoning” (Dahlstrom, 2014; p. 13614).

Research has shown that narratives are easier to understand and remember compared with standard technical and scientific communication (Schank and Abelson, 1995). Our propensity to rely on narratives may be a product of evolution, where narratives conferred an adaptive

___________________

110 Cognitive schema are mental structures or models we develop over time from our experiences and knowledge. These schemas help us organize and interpret all the information we encounter, forming the basis of how we understand the world.

111 “Logical-scientific information” is defined in the article as information based on facts, while narrative information relies on story-telling.

advantage by enabling humans to construct possible realities, model cause-and-effect relationships, and understand complex social interactions. The use of narratives has been increasing in science education, where they are better able to evoke emotional and personalized responses than conventional instruction (Jones and Crow, 2017). They are also effective in health communications, where people can more easily relate to narratives in understanding and adopting healthier behaviors.

Once people are done with formal schooling, they get most of their information about science and engineering from the mass media. To compete for attention, the mass media tend to rely on stories, anecdotes, personalization, and other narrative structures, reflecting the power of narratives to capture our attention and shape our beliefs.

Engineering is particularly amenable to a narrative approach. Individuals and teams are engaged not only in understanding causes and effects but also in adapting those causes and effects to human advantage. Stories of exploration, effort, enlightenment, and triumph are commonplace in engineering. Such narratives offer many opportunities to convey to non-engineers the extraordinary impacts of engineering on society.

The narrative approach, though, must be used thoughtfully and with full appreciation of its potential pitfalls. Dahlstrom and Ho (2012) identify three primary ethical issues related to the use of narrative in science communication. First, they emphasize the need to consider the underlying purpose of using narrative: whether it is intended for comprehension or persuasion. They highlight that while narratives can make scientific information more relatable and understandable, they can also be used to subtly influence or persuade audiences, which raises ethical concerns about manipulation and the communicator’s intent.

The authors also discuss the importance of maintaining accuracy within narratives. They point out that narratives can sometimes oversimplify complex concepts or lead to overgeneralization, which can result in misinformation. Ethical communication should strive to balance the engaging nature of narratives with the necessity of accurate and representative information.

And last, Dahlstrom and Ho pose the question of whether narratives should be used in science communication at all, given their potential to manipulate. They argue that while narratives are a powerful tool for engagement and understanding, their use must be carefully considered to avoid misleading audiences. Science communicators need to weigh the benefits of narrative storytelling against the ethical implications of influencing public perception and behavior through emotionally compelling stories.

Using narratives to communicate scientific and technological information thus requires careful consideration of its ethical dimensions. These considerations include the honesty of the content, where communicators must avoid misrepresentation and provide sufficient context to prevent misleading the audience. Clarity and accessibility are also crucial. Communicators should use understandable language, avoid jargon, and transparently convey the information’s limitations and uncertainties. To maintain objectivity, they should be mindful of personal and institutional biases, present balanced views, and disclose any conflicts of interest.

Respect for the audience is paramount, recognizing diverse backgrounds and perspectives, and engaging them in ways that empower critical thinking and informed decision-making. Ethical use of emotional appeal involves balancing emotion with facts and avoiding fearmongering. Cultural sensitivity requires respecting cultural differences and including diverse voices in narratives. Privacy and consent must be respected, particularly in sharing stories involving individuals. Finally, ethical storytelling must consider its impact on the people and

communities towards whom the outreach is directed. Addressing these ethical considerations ensures responsible, trustworthy, and respectful communication, ultimately fostering a more informed and engaged public.

REACHING DIVERSE AUDIENCES

Changing the Conversation and Messaging for Engineering point out that messages about engineering, to be effective, must be tailored to appeal to their target audience (NAE, 208, 2013). These audiences are briefly noted below, along with groups that have the potential to be communicators.

K–12 Students

While a small but growing number of K–12 students have received formal education in engineering, many others develop conceptions of engineering other ways, including, in part, via the science and mathematics classes they take in middle and high school. This direct and indirect exposure to engineering has the potential to increase awareness of the work of engineers, boost youth interest in pursuing engineering as a career, and increase the technological literacy of all students (NAE/NRC, 2009).

Because it is so well suited to hands-on activities, engineering education can be inherently attractive to K–12 students. It can teach students that problems have many potential solutions, and that careful analysis and modeling can both suggest and differentiate among those solutions. It can complement the teaching of science, mathematics, and other subjects and demonstrate the social, economic, and environmental impacts of technical endeavors. And it can inculcate habits of mind that are essential in the 21st century: systems thinking, creativity, optimism, collaboration, communication, and consideration of ethical issues. Both educators and guidance counselors should be part of this effort.

As mentioned earlier, effective messages about engineering may differ between boys and girls. For example, research suggests that, from an early age, girls are less interested in subjects that are characterized by male gender stereotypes, suggesting the need to address these stereotypes early in children’s education (Master et al., 2021).

One existing messaging effort is “Engineers Week”, which “is dedicated to ensuring a diverse and well-educated future engineering workforce” through programs intended to stimulate interest in the field, particularly in in K–12 students (NSPE, 2024). DiscoverE, one of the organizations promoting “EWeek”, posts educator and volunteer toolkits, event primers, promotional materials, and other resources for download in association with the event (DiscoverE, 2024).

There are also other strategies for engaging young people from all segments of society in the pursuit of engineering as a career, including programs such as Project Lead the Way,112 which gives grants to elementary, middle, and high schools to implement engineering and other STEM curriculum as well as providing professional development for teachers. These strategies are executed at various points in the academic path and with varying levels of success and access to the necessary resources (people, expertise, and funding) to execute. Some of the most impactful strategies include participation in hands-on, project-based engineering camps, courses,

___________________

workshops, and work experiences and in some instances represent partnerships between schools, universities, communities, the private sector, and government agencies (American Progress, 2024; NASEM, 2019). The Institute for Broadening Participation hosts on the web a searchable database with more than 1,000 fully funded STEM programs for K–12, undergraduates, graduate students, postdocs, and faculty.113

Members of Underrepresented Groups

Women, African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, people with disabilities, and members of other minority groups remain significantly underrepresented in engineering in the United States. According to the most recent data collected by the National Science Foundation, women still make up only about 16 percent of college-educated engineers in the United States, and in 2020 women, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native students received just 24 percent, 5 percent, 14, and 0.3 percent of engineering bachelor’s degrees, respectively, well below the representation of these groups among the U.S. college-age population (NCSES, 2023). Some signs of diversification have appeared in recent years; for example, the number of bachelor’s degrees awarded to women in engineering more than doubled from nearly 15,000 in 2011 to more than 31,000 in 2020, and from 2017 to 2021 the number of Hispanic students pursuing graduate degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) rose by about 50 percent. But much more needs to be done before these and other groups will be represented proportionately in engineering.

Messages about engineering need to be appealing and believable (DiscoverE, 2023) and to excite the interest of students from underrepresented groups if they are to positively affect perceptions, persistence, and the pursuit of engineering careers (NAS/NAE/IOM, 2011). Thus, targeted messages about engineering to underrepresented groups might emphasize the opportunity to make a difference in the world or the chance for everyone to engage in meaningful, collaborative, and creative work, while also providing financial security. Beyond persuasive messages, underrepresented groups also need welcoming and inclusive academic and professional environments to make the make the message that “engineering is for everyone” credible (DiscoverE, 2023). This requires effort across all communities involved in engineering and engineering education.

It is also important to note that messages about engineering targeted to underrepresented groups are more effective when they are delivered by people who belong to the same underrepresented group as the intended audience (DePass and Chubin, 2015). Students more readily empathize with teachers, counselors, mentors, and advisors who are like themselves. Furthermore, representation must go beyond those who stand in front of the classroom. As Shanahan and her colleagues wrote in their 2013 article, “To be successful, organizations must go beyond asking nontraditional members to volunteer; such members must be recruited to leadership positions, have the ability to drive changes in existing programming and the organization overall, have the expectation of being listened to, and be recognized for their contributions to the society and the discipline” (Bogue, et al., 2013, p. 14).

As the U.S. population becomes increasingly diverse, engineering needs to account for the values and concerns of all people. This objective can be achieved most effectively by having an engineering workforce that reflects that diversity, which means reaching the members of

___________________

underrepresented groups with the messages, information, and assistance they need to help them join the field.

Engineering Schools

Engineering schools have lines of communication not only to their own faculty members and students but to K–12 teachers, counselors, and students and to their alumni. There are more than 300 ABET114-accredited engineering schools in the United States, all of which perform outreach of some sort to prospective students and the wider world. In addition, these schools have connections to their local communities, to other disciplines within their college, and to national and international engineering organizations. Engineering schools have many ways of tailoring and disseminating messages about the impacts of engineering both on individuals and on society as a whole.

As recommended in Messaging for Engineering, engineering schools can hold new-faculty orientation workshops or other faculty training sessions (NAE, 2013). They can direct messages about engineering not only to their own students but to university students who have not decided on a major or are majoring in different subjects. They can work with schools of education so that future K–12 teachers are aware of what engineering is and what engineers do. They can encourage engineering undergraduates to volunteer in K–12 classrooms and get involved in the Grand Challenges for Engineering. Such students can publicly disseminate the message of engineering’s impact both during their school years and subsequently.

Science and Technology Centers

Along with formal schooling and the mass media, the hundreds of museums and other science and technology centers in the United States are a major source of information about STEM for children, adolescents, and adults. These organizations have the potential to teach visitors of all ages about engineering and its role in shaping modern life. When designing new exhibits or revising existing ones, they can highlight the role of engineering in engaging and memorable ways. They can also involve engineers from academia, professional societies, and industry in the review of exhibits and in outreach activities. In addition, they have great expertise in messaging about science and technology and could advise the other sectors of the engineering community in how to craft messages that have long-lasting and beneficial effects.

Industry

Technology-related companies rely heavily on engineers, not only for traditional engineering tasks but for company leadership and guidance. Many of these companies undertake education, job recruitment, and marketing outreach efforts to attract skilled personnel and to build the pipeline that will create future engineers. As a result, they have many opportunities to shape the messages and information that people receive about engineering.

Companies can feature engineers and engineering in outreach to K–12 students, colleges, and engineering societies. They can partner with other segments of the engineering community,

___________________

114 ABET, formerly the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, is a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization that accredits “college and university programs in the disciplines of applied and natural science, computing, engineering and engineering technology at the associate, bachelor’s and master’s degree levels” (https://www.abet.org/about-abet/).

such as professional societies and colleges of engineering. They can collaborate among themselves through such organizations as the Business Roundtable or the Council on Competitiveness as well as providing their engineers with the opportunities and support to engage with other parts of the engineering community, including students.

Government Agencies

As with companies, government agencies rely on engineers in carrying out their missions and have many opportunities to shape the messages that students and members of the public receive about engineering. Messaging for Engineering urged government agencies to “incorporate the CTC messages in education and outreach programs . . . and in all STEM-related government programs that support hands-on experiments and engineering design activities for schools, libraries, scout troops, civic centers, and other organizations” (NAE, 2013, p. 55). Government agencies can also work with other segments of the engineering community, including industry partners, in outreach programs, and they can create incentives for recipients of federal grants and contracts to convey accurate information about engineering. Engineers employed by the federal government can speak and provide mentoring to students and their teachers. In these and other ways, government agencies can help demonstrate the extraordinary impacts of engineering in the past and the potential for engineering to further improve human life.

Engineering Professional Societies

Hundreds of thousands of engineers belong to professional societies, providing a unique opportunity to coordinate educational and public outreach about engineering. With training, the members of these societies can become effective ambassadors in conveying messages about the value and importance of engineering.

As is recommended in Messaging for Engineering, societies should educate their members about public communication and effective messages (NAE, 2013). This can be done through sessions at conferences, through society publications, and through local chapters. Societies can conduct meetings and workshops with policymakers, educators, and members of the public. Messages about the engineering profession as a whole are preferable, but messages about individual disciplines can be helpful as well.

The American Society for Engineering Education has a unique position in representing the profession as a whole rather than specific disciplines. In addition, diversity-based societies provide an opportunity to reach out specifically to groups underrepresented in engineering, with coordination between discipline-based and diversity-based societies enabling greater coordination and dissemination of messages. Box 5-1 provides a list of such organizations.

BOX 5-1

Diversity-Oriented Engineering Organizations

Women-Oriented

American Association of University Women

Society for Women Engineers

Women in Global Science and Technology

Women in Technology International

Racial/Ethnic Minority-Oriented

American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES)

Great Minds in STEM (GMiS)

Inclusive STEMM Ecosystems for Equity & Diversity (ISEED)

INROADS

National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering (NACME)

National Association of Multicultural Engineering Program Advocates

National GEM Consortium

National Society of Black Engineers

Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS)

Society of Asian Scientists and Engineers (SASE)

Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers

Society of Mexican American Engineers and Scientists (Latinos in Science and Engineering)

LGBTQ+-Oriented

500 Queer Scientists

Out in STEM (OSTEM)

Out to Innovate (formerly National Organization of Gay and Lesbian Scientists and Technical Professionals [NOGLSTP])

Pride in STEM

Disability-Oriented

AccessSTEM

Entry Point!

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH TO DEVELOPING EXAMPLE OUTREACH MATERIALS

The statement of task directed the committee to “[p]rovide guidance on how to reach and engage diverse audiences . . ., promote better understanding of the vital role of engineering in government, business, and society; and engage young people from all segments of society to encourage pursuing a career in engineering.” As noted in Chapter 1, NSF provided additional guidance on this element of the task in their charge to the committee. Dr. Susan Margulies, NSF’s Assistant Director for Engineering, indicated that the committee should focus on “stories and people” in its impact descriptions, noting that stories can illustrate how fundamental research and innovative education modalities translate into societal benefits; propel prospective visions and new research directions; embolden creativity and risk; and, most importantly, inspire, motivate, and connect (Margulies, 2021). In keeping with the literature on communications

summarized in this chapter, the committee sought to identify messages with this focus that were accurate, accessible, clear, engaging, and relevant to diverse audiences.

Several previous National Academies reports and other scholarship have addressed the challenges of and strategies for communicating scientific and technical information to these audiences, including NAE reports that offered observations specific to engineering. The committee did not repeat this work but rather concentrated on developing information and materials directly relevant to NSF’s role in bringing about engineering impacts on society. It was informed by the scholarship summarized in this chapter and the additional outreach-specific literature presented in the Appendix B sections titled “Rationale Behind Content Choices”.

In addition to the descriptions of the achievements, stories, and people presented in the impact descriptions presented in Chapter 4, the committee contracted with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science (Alda Center) and with the MIT Office of Engineering Outreach Programs to develop a set of example materials for NSF to consider in their outreach efforts. These materials, which were prepared under the supervision of committee members Laura Lindenfeld and Eboney Hearn, address topics and people identified by both the exemplary impacts narratives and in the symposium in order to give NSF a broader range of alternatives with which to work. Note that these materials are presented as examples only and have not been subject to the refinement that would accompany a professional product. Furthermore, they have not been subject to review by the NSF and should not be considered as representing the agency’s point of view.

As part of this task, an informal, small-scale assessment of draft materials was conducted with seventh- through twelfth-grade students. These students attended public schools in either Boston, Cambridge, or Lawrence, Massachusetts, and were from underrepresented or underserved backgrounds in STEM. They were participants in a STEM outreach program that gave them exposure to a variety of disciplines in engineering and thus had already shown an interest in exploring topics in engineering and science.

Participants provided feedback via an anonymous questionaire after reviewing the draft materials along with documents that described the content and objectives of the materials. This instrument was composed of the questions below and was administered separately for each example reviewed.

- What did you appreciate about content in sample X?

- What did you wonder about content in sample X? What would you change?

- How was sample X successful in meeting its objective?

- In what ways is media/communication in sample X a good fit for a middle or high school audience? In what ways could it fit better?

- How do you typically engage STEM content inside and outside of school?

- When engaging with STEM content, what type of information have you found to be helpful in building interest and knowledge in STEM?

Responses were taken into consideration by the Alda Center as they refined the outreach materials.

Notable takeaways from the responses included the value of providing videos and blogs with engineers from diverse backgrounds to promote a sense of belonging in engineering and a sense of resilience. Content creators were encouraged to consider using short videos that embedded humor to keep the attention of high schoolers and encourage them to reshare content.

In addition, it was suggested that content be accompanied with resources and information on how to get involved in engineering or STEM programs in the local community or through a formal program.

EXAMPLE OUTREACH MATERIALS

Five examples of outreach materials were developed. They are titled

- Meet an Engineer

- Queen of Carbon Science “Family Tree”

- Earthquake Shake Table

- Grand Challenges

- Extraordinary Impacts of Engineering

The examples are aimed at different segments of the general public, with an emphasis on students and on groups that may otherwise be poorly informed about engineering and engineers. They use a variety of media (short videos, interactive graphics, blog posts, workbooks, etc.) and take different approaches (inspirational, educational, humorous, etc.) to engage their audiences. Their content is briefly described in the sections below and summarized in Table 5-1. Complete descriptions of the examples are contained in Appendix B. The text supporting them details the target audiences, content objectives, media format, pitch outline, script, and the rationale behind the content choices, plus additional information and citations to literature consulted. Online materials accompany the examples.

| Title | Intended audience[s] | Media Format | Content Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meet an Engineer | Young people (high school) in historically marginalized groups in STEM (especially underrepresented gender/racial/ethnic groups) | Video sharing social media platform video (2–5 minutes long) | Interview with a high-profile, NSF-funded engineer from an underrepresented group |

| Queen of Carbon Science “Family Tree” (inspired by the work of Millie Dresselhaus) | High schoolers (especially young women) | Clickable-interactive image-based web post | Graphic of the many forms of carbon connected in a “family tree”-type diagram illustrating their real-world applications |

| Earthquake Shake Table | General public (teens and up), especially those who live in high-hazard earthquake areas | Video sharing social media platform short-form video (2 minutes) | Video illustrating how structures are endangered by earthquakes and how shake tables can be used to test designs |

| Grand Challenges in Engineering | Elementary and middle school students | Fill-in-the-blank style workbook for elementary students; blog posts for middle school students | Workbook with prompts encouraging students to identify a problem and then draw a device that solves the problem; blog posts highlighting stories of inspiring engineers |

| Extraordinary Impacts of Engineering | Gen Z/younger millennials | Video sharing social media platform short-form video (2 minutes) | Animated video illustrating how the technology of an everyday device like a phone has advanced |

Example 1: Meet an Engineer

This content is aimed at young high school students in STEM, especially those from historically marginalized backgrounds. The objectives are to redefine the image of engineers, emphasizing their social, creative nature and diverse interests beyond work, aiming to resonate with the audience by highlighting shared identities and interests. This is achieved by showcasing profiles of engineers who resemble them and share their passions, thereby fostering interest in engineering careers. Through short-form video content that can be shared on social media platforms, the intention is to link engineering with awe and curiosity, moving beyond mere math and science proficiency and emphasizing problem-solving and creativity [short-form video link]. An interview would be conducted with a high-profile engineer who has received funding from NSF and belongs to an underrepresented group, inspired by the NSF’s Science Happens Here campaign. The pre-designed interview, with a sample outline script and questions, would take place during an activity that interests the engineer and also appeals to the target audience. The editing for this interview would highlight the engineer’s personal story while also connecting it to broader themes about the essence of engineering and the traits of curiosity and creativity in individuals.

In the sample outreach material, Gary May, the Chancellor of the University of California, Davis, and a former professor and Dean of Georgia Tech’s College of Engineering, was interviewed. In addition to highlighting his professional accolades—especially in increasing opportunities for groups that are historically underrepresented in the engineering field—the video includes more personal information, for instance, on May’s path to engineering from a family of non-engineers and his life-long interests in comic books, Star Trek, and “ways to imagine a different world.”

The rationale behind this content is to emphasize the scientific and societal benefits of diversity in engineering, citing increased productivity, improved cognitive performance, and innovation gains. However, the engineering workforce fails to reflect the diversity of the U.S. population, hindering innovation. To address this, the content seeks to amplify underrepresented voices and challenge stereotypes by featuring an engineer who shares interests and identities with high school students. Drawing from best practices in science communication and social identity theory, the content aims to foster trust through warmth and authenticity. Additionally, it prioritizes culturally relevant communication to ensure accessibility and resonance with the audience’s everyday reality. By showcasing diverse narratives and engaging storytelling inspired by initiatives like The Story Collider, the content aims to inspire and empower underrepresented groups to pursue careers in STEM.

A still image from the video interview with Dr. May is shown in Figure 5-1.

Example 2: Queen of Carbon Science “Family Tree”

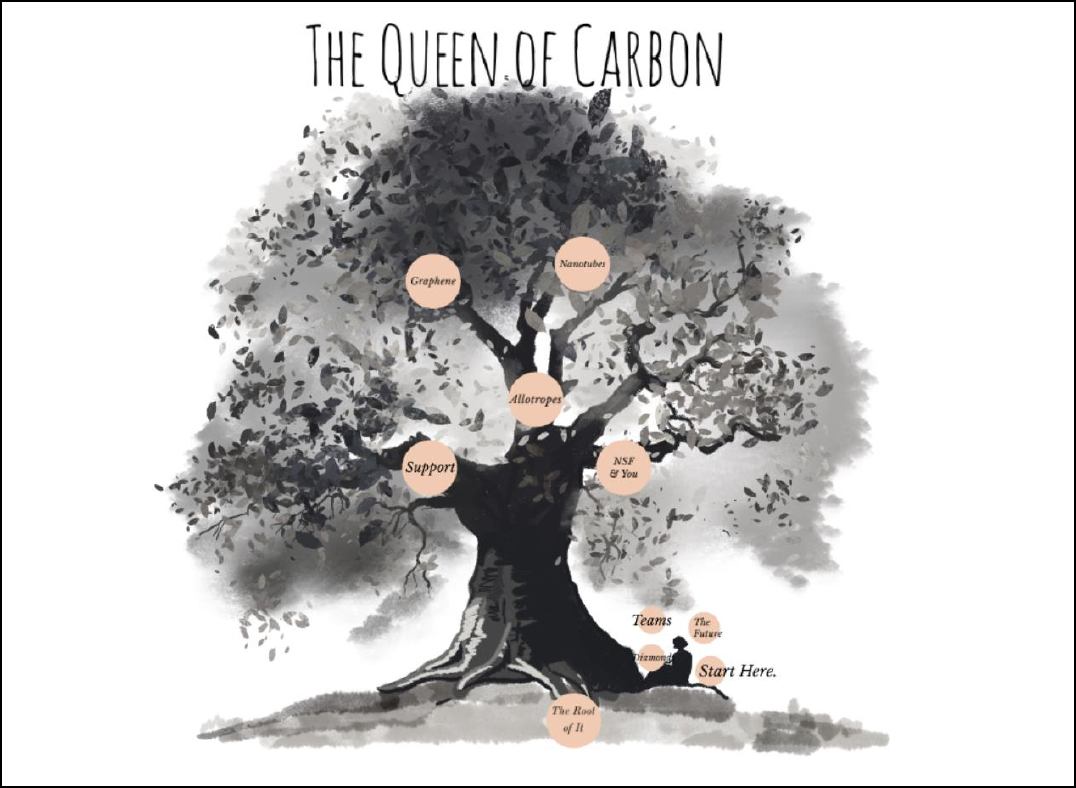

This content is aimed at high school students, especially women, with the objectives of reframing basic engineering research as having significant real-world impacts, challenging the perception of engineers as solitary geniuses by highlighting stories of individuals who have been influenced by and have influenced many others, and thus portraying engineering as a collaborative and social endeavor. Importantly, there is a focus on promoting gender equity by ensuring that the narratives of engineering history include the contributions of women. The content will be in a clickable interactive image format for web posts [interactive graphic download Windows link and Apple OS link]. The example showcases various forms of carbon in a “family tree” diagram, demonstrating their practical applications. Engineers and scientists associated with these materials are depicted within the tree, emphasizing that engineering is a collaborative endeavor rather than the work of a lone prodigy. Dr. Millie Dresselhaus’s significant contributions to engineering, particularly those supported by NSF, are highlighted. The interactive graphic depicts a woman, symbolizing Dr. Millie Dresselhaus, under a tree, writing with a pencil. Clicking on the graphic reveals information about carbon, its uses, and the ways in which it inspired Dresselhaus. The graphic zooms in on the pencil tip to discuss graphite and Dresselhaus’s specific work with this material. The tree’s roots represent carbon storage, leading to insights on graphite compounds and so on. The graphic integrates Dresselhaus’s contributions and mentions her influence on Nobel Prize-winning researchers. It concludes with a summary of Dresselhaus’s accomplishments as a woman in engineering. The rationale behind the content choices emphasizes the importance of portraying a diverse history of engineering, challenging gender stereotypes, and expanding the image of engineering beyond traditional narratives. It aims to engage girls by highlighting the biographies of female engineers like Millie Dresselhaus and showcasing engineering as a communal, social process. Visuals play a crucial role in engaging audiences, but it is essential to adhere to best practices in visual design to ensure accessibility and effectiveness.

The opening image of the example’s interactive graphic is contained in Figure 5-2.

Example 3: Earthquake Shake Table

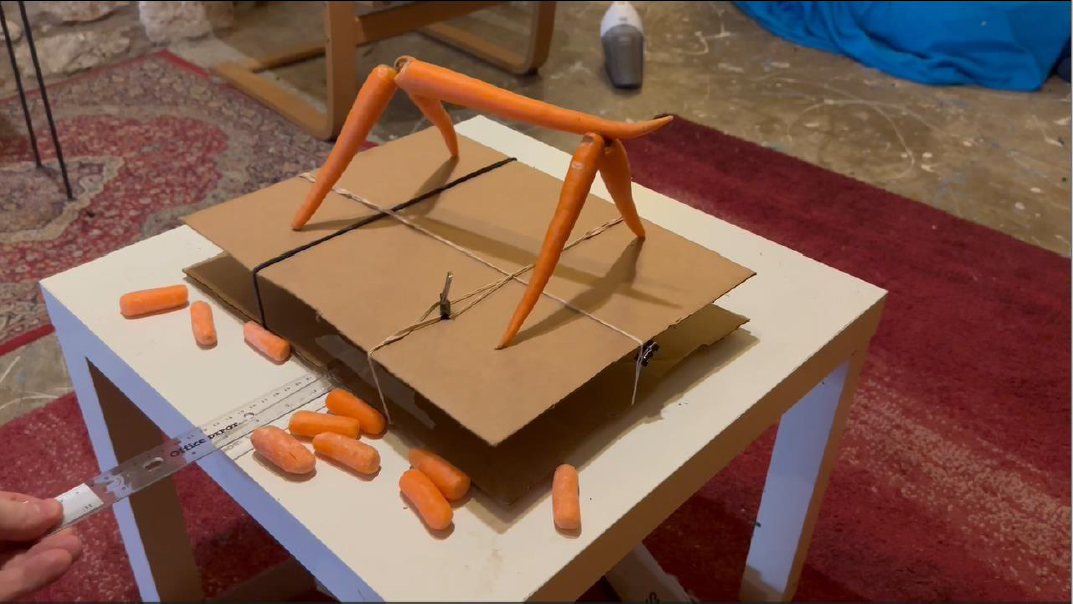

This content targets the general public, particularly teens and older individuals, who live in high hazard earthquake areas of the United States. It aims to highlight impressive yet not-widely-known innovations and societal impacts supported by NSF investments, showcasing the “cool-factor” of the country’s largest shake table to inspire awe and appreciation for engineering’s role in earthquake risk mitigation. Using the popular “Did you know?” format, these short-form videos are suitable for social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram reels, and YouTube Shorts. The sample content features a video highlighting the largest three-dimensional shake table in the United States, demonstrating how engineers simulate earthquake conditions to strengthen buildings [video link]. The pitch emphasizes that such work is possible thanks to advances in engineering. Optionally, a follow-up video could depict a presenter constructing a model building and testing it on a do-it-yourself shake table (demonstrated in brief in the example video).

The video takes a humorous approach to engage a general audience that is not already interested in engineering, using research on persuasion to change attitudes. Using platforms like TikTok and concise, short-form, “infotainment”-style narration, the content aims to stimulate and

maintain the interest of the target audience. The focus on attention-grabbing content—earthquakes—aims to evoke curiosity while being mindful of avoiding audience burnout.

A still from the video illustrating a simple “homemade” shake table is shown in Figure 5-3.

Example 4: Grand Challenges in Engineering

This content is aimed at elementary and middle school students to challenge the misconception that the lack of representation in engineering is solely a “pipeline” issue, emphasizing the need for culturally relevant pedagogy in STEM education. It seeks to inspire young individuals to embrace their cultural identities and bring their whole selves into STEM spaces, fostering inclusivity and diversity within the field. The content would be in two formats, a workbook for elementary school students (not depicted) and blog posts for middle school students [blog post link]. Using the NAE Grand Challenges for Engineering115 as an inspiration, the workbook would aim to demonstrate that anyone can think like an engineer, guiding younger readers through design steps using drawings to solve real-world problems that they care about. The students’ drawings might be showcased anonymously on a moderated NSF public website, connecting their contributions to NSF-funded efforts. The workbook would conclude with encouragement to continue applying engineering thinking in their lives. The blog posts would introduce grand challenges facing the world, featuring underrepresented engineers working on solutions and highlighting past and recent innovations. The examples would emphasize the richness of engineering through diversity and the impact of engineers using their backgrounds and perspectives to address global issues. The goal driving the content choices is to engage young people in engineering by using problem-posing methodology, allowing them to take on

___________________

the role of experts and drawing on their funds of knowledge and cultural connections. Art-based communication enhances creativity and learning outcomes, aligning with multimodal learning approaches. By positioning the audience as holders of knowledge and emphasizing engineering’s creative potential, the content is intended to develop participants’ engineering identity and increase their self-efficacy in the field. It also highlights the community-minded aspects of engineering to attract historically marginalized students. The content seeks to stimulate interest in engineering by providing both examples and direct experiences, recognizing the importance of embracing diverse forms of knowledge to address society’s challenges and empowering young people in engineering spaces.

Two photographs used in the illustrative blog posts are presented in Figure 5-4.

SOURCE: Dr. Rory Cooper.

Example 5: Extraordinary Impacts of Engineering

The content is aimed at “Gen Z” and younger millennials with the objective of using narratives to frame engineering innovations as beneficial to people’s everyday lives. Using TikTok-style short-form videos/reels [short form video link], the content is intended to engage viewers through nostalgia, humor, and concise language. The introduction sets the scene by showcasing life without such modern technology as smartphones. Given the importance of keeping videos short to maximize engagement, it uses nostalgia, particularly targeting Gen Z and millennials through connections to 2000s “throwbacks,” to captivate the audience emotionally and ensure the video’s success. Two video outlines are described. The first video presents a journey through time, showcasing clips from different decades depicting people using various technologies, from payphones to smartphones, highlighting the evolution of technology and its impact on our lives. The aim is to illustrate the advances in technology and the role of engineers in shaping our modern world. The second video uses an educational animation in a humorous style, reminiscent of popular educational animations from past decades such as The Disney

Channel’s Healthy Handbook, BrainPOP, and Wild Kratts productions. This approach is intended to appeal to nostalgia while providing informative content in an engaging and entertaining format. The content is designed to address the lack of understanding among the general public regarding the role of engineers and the social value of engineering innovations. Drawing from persuasion techniques like emphasis framing, the video highlights the societal impacts of engineering in a humorous manner, encouraging audiences to imagine life without certain technologies. It incorporates participatory elements and interactive platforms such as TikTok to engage audiences effectively, recognizing the importance of co-creating content with users. Additionally, research on humor in science communication informs the use of humor to enhance engagement; that said, caution is advised in order to avoid the video backfiring, especially when correcting misinformation. Ultimately, this content is intended to make engineering more relatable and accessible by framing it as an everyday experience and taking advantage of social media as a popular communication channel for younger audiences.

Figure 5-5 is a still from an example short-form reel style video illustrating how the modern smartphone has evolved to contain a number of functions previously found in separate devices.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee’s statement of task directed it to “offer conclusions and recommendations on how to best promote understanding of engineering’s place in society and how NSF contributes to it.” The information developed in this chapter and the additional material presented in the “Rationale Behind Content Choices” sections accompanying the examples of engineering impacts on society outreach materials contained in Appendix B led the committee to the following conclusions:

- There is an opportunity to change the way that engineers and engineering are perceived by the general public by highlighting the many ways that engineering affects everyday life, the contributions that engineers make to improving those lives, and the role that investments in engineering education and research play in making these contributions possible.

- Outreach efforts that are grounded in the research on engagement and communication are more likely to reach target audiences and have the intended impact. Research indicates that efforts that use or highlight people with whom or content with which target audiences can relate are more effective.

These materials also form the basis for the following recommendations regarding the communication of engineering impacts on society to diverse audiences:

NSF, in its outreach efforts regarding the support of engineering education and research, should

- draw upon the literature and experts on public engagement and communication to better target its messaging.

- increase the participation and diversity of organizations, people, and voices who have not been well represented in the engineering profession in its messaging.

- employ communication forms (short-form videos and media that can be consumed on phones for example) and forums (including social media platforms) that are used by its target audiences.

- feature diverse and relatable people and stories that illustrate how engineering is making everyday life better and how engineers improve the lives of others.

- incorporate tracking of the effectiveness of specific messaging efforts into outreach efforts.

REFERENCES

American Progress. 2024. K-12 work-based learning opportunities: A 50-state scan of 2023 legislative action. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/k-12-work-based-learning-opportunities-a-50-state-scan-of-2023-legislative-action/ (accessed May 31, 2024).

Baranowski, M. 2011. Rebranding engineering: Challenges and opportunities. The Bridge 41(2):12–16. Available online at www.nae.edu/Publications/Bridge/51063/51088.aspx (accessed April 15, 2024).

Baranowski, M., and J. Delorey. 2007. Because dreams need doing: New messages for enhancing public understanding of engineering. Project Report for the NAE Committee on Improving Public Understanding of Engineering Messaging.

Bogue, B., E. Cady, and B. Shanahan. 2013. Professional societies making engineering outreach work: Good input results in good output. Leadership and Management in Engineering 13:11–26.

Chong, D., and J. N. Druckman. 2007. Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science 10:103–126.

Dahlstrom, M. F. 2014. Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(Suppl 4):13614–13620.

Dahlstrom, M. F., and S. S. Ho. 2012. Ethical considerations of using narrative to communicate science. Science Communication 34(5):592-617.

DiscoverE. 2023. Messages matter: Effective messages for reaching tomorrow’s innovators. https://discovere.org/messages-matter/ (accessed March 20, 2024).

DiscoverE. 2024. Engineers Week. https://discovere.org/programs/engineers-week/ (accessed May 29, 2024).

DePass, A. L., and D. E. Chubin (eds.). 2015. Understanding interventions that broaden participation in research careers, Vol. VI: Translating research, impacting practice. Summary of a conference, San Diego, CA.

Innovative Research Group. 2017. Public perceptions of engineers and engineering. https://engineerscanada.ca/sites/default/files/public-perceptions-of-engineers-and-engineering.pdf (accessed April 15, 2024).

Jones, M. D., and D. A. Crow. 2017. How can we use the “science of stories” to produce persuasive scientific stories? Palgrave Communications 3(53) https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0047-7.

Lachney, M., and D. Nieusma. 2015. Engineering bait-and-switch: K-12 recruitment strategies meet university curricula and culture. 2015 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition. https://peer.asee.org/engineering-bait-and-switch-k-12-recruitment-strategies-meet-university-curricula-and-culture (accessed March 7, 2024).

Master, A., A. N. Meltzoff, and S. Cheryan. 2021. Gender stereotypes about interests start early and cause gender disparities in computer science and engineering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(48):e2100030118.

Margulies S. 2021. Engineering impacts. Presentation before the National Academies Committee on Extraordinary Engineering Impacts on Society. Washington, DC. September 27.

NAE (National Academy of Engineering). 2008. Changing the conversation: Messages for improving public understanding of engineering. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12187 (accessed April 15, 2024).

NAE. 2013. Messaging for engineering: From research to action. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NAE/NRC (National Academy of Engineering and National Research Council). 2009. Engineering in K–12 education: Understanding the status and improving the prospects. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12635.

NAS/NAE/IOM (National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine). 2011. Expanding underrepresented minority participation: America’s science and technology talent at the crossroads. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12984.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine) 2017. Communicating science effectively: A research agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/23674.

NASEM. 2019. Minority serving institutions: America’s underutilized resource for strengthening the STEM workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25257.

NCSES (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics). 2023. Diversity and STEM: Women, minorities, and persons with disabilities 2023. Special Report NSF 23-315. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation. https://ncses.nsf.gov/wmpd (accessed April 15, 2024).

NSPE (National Society of Professional Engineers). 2024. Engineers Week. https://www.nspe.org/resources/partners-and-state-societies/engineers-week (accessed May 29, 2024).

Schank, G., and R. P. Abelson. 1995. Knowledge and memory: The real story. In Robert S. Wyer, Jr. (ed.), Knowledge and memory: The real story. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Pp. 1–85.

Scheufele, D. A. 2014. Science communication as political communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(supplement_4):13585-13592.

Vest, C. 2011. The image problem for engineering: An overview. The Bridge 41(2):5–11.