Failure Analysis of the Arecibo Observatory 305-Meter Telescope Collapse (2024)

Chapter: 2 The Collapse: What Happened

2

The Collapse: What Happened

ARECIBO TELESCOPE FAILURE SEQUENCE

The more than 3-year sequence of selected events that led to the ultimate failure of the Arecibo Telescope is illustrated chronologically in Figure 2-1. As can be seen from this timeline, the final cable failures themselves that caused the Arecibo Telescope’s collapse comprise only 10 percent of the more than 3-year Arecibo Telescope failure sequence timeline.

HURRICANE MARIA HITS THE ARECIBO TELESCOPE

The Arecibo Telescope’s failure sequence timeline begins when Hurricane Maria hit the Arecibo Telescope on September 20, 2017, almost 39 months before the Arecibo Telescope’s collapse. Major natural disasters, including hurricanes, earthquakes, and floods, represent a significant challenge to the integrity of aging structures, especially those designed and built decades before the disaster and which have reached or exceeded their original design service life. Among others, these challenges include the predictability of their magnitudes or forces, orientation of the events with respect to the structure, location, topography, incidence, occurrences, and redundancy of the structure. The Arecibo Telescope survived many natural disasters, including multiple earthquakes, one of which was 6.4 magnitude, and hurricanes. The most significant was Hurricane Maria. The committee could not discern exactly what goals, guidelines, and/or instructions were followed by the contracted and onsite engineers and inspectors that inspected the Arecibo Telescope after each natural disaster, and it is not clear that any “red lines” or critical thresholds were established. As discussed below, no reference or owner’s manual was ever prepared for the facility by the original designers or the engineers involved in the upgrades to guide a series of contract operators on the risks or inspections of structurally critical components.

Maria subjected the Arecibo Telescope to winds of between 105 and 118 mph, with the source of this uncertainty in wind speed discussed below. After every natural disaster, the Arecibo Telescope was at least visually inspected by the staff and sometimes by outside engineers, as it was after Maria. Although the Arecibo Telescope exhibited evidence of the effects of these natural disasters, every inspection concluded that no significant damage had jeopardized the Arecibo Telescope’s structural integrity.

Based on a review of available records, the winds of Hurricane Maria subjected the Arecibo Telescope’s cables to the highest structural stress they had ever endured since it opened in 1963.1 While the Arecibo Telescope weather station produced the only available local wind speed data, varying analyses have estimated differing peak wind speeds of 105 mph,2 108 mph,3 110 mph,4,5,6 and 118 mph.7 The variance in reported wind speed is dependent on the time interval of the measurement (3-sec, 15-sec, 1-min, 2-min, 10-min, or “fastest mile”) or is a reporting of the mean value of the measurements. Additional discussion of reported wind speed is in Appendix D. The Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates (WJE) and Thornton Tomasetti, Inc. (TT) reports (hereafter “WJE Report” and “TT Final Report,” respectively) present different estimates of the “peak” or “highest instantaneous” wind speed seen by the Arecibo Telescope. These differing estimates of the peak wind speed at the Arecibo Telescope during Maria result from a concurrent Arecibo Telescope weather instrument failure. The previously cited peak wind speed estimates are based on the same Arecibo Telescope Doppler data recorded at 15-second intervals.8 Arecibo Telescope’s telescope platform was equipped with a weather station that measured wind speed with two independent instruments.9 Unfortunately, one of these instruments, the anemometer, whose measurements of wind speed were logged every second,10 “failed approximately one hour before the peak of the storm,”11 so the 15-second interval Doppler data has been used to estimate what the actual peak wind speed in between the 15-second measuring intervals would have been. Since the Arecibo Telescope’s structural “wind load is proportional to the square of the wind speed and to the structure’s area modified by a drag coefficient,”12 going from a 105 mph to 118 mph peak wind speed increases the calculated peak drag forces from Hurricane Maria by more than 25 percent.

The maximum wind speed the Arecibo Telescope was designed to withstand, and with what factor of safety, is unclear from the records and has changed with upgrades. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) observed, “It is worth reflecting on the original design that considered the “survival” condition to be 100 mph winds.”13 After the Gregorian dome upgrades, the “survival loading” condition included wind effects from 100 mph winds.14 However, TT reported, “The structural drawings for the original structure indicate a design wind speed of 140 mph.”15 TT reports that after the Gregorian upgrade, “A&W confirmed the two speeds of 110 mph and 123 mph for the global and local design of the upgrade respectively and, to our knowledge, the final design was based on those wind speeds.”16 A summary of the available documentation is illustrated in Figure 2-2.17

Because of the high wind speeds noted above, TT devoted an entire appendix to wind loading on the Arecibo Telescope from Maria.18

___________________

1 Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates (WJE), 2021, Auxiliary Main Cable Socket Failure Investigation, WJE No. 2020.5191, June 21 (hereafter “WJE Report”), p. 16.

2 WJE Report, p. 6.

3 Thornton Tomasetti, Inc. (TT), 2022, Arecibo Telescope Collapse: Forensic Investigation, NN20209, prepared by J. Abruzzo, L. Cao, and P.E. Pierre Ghisbain, July 25, https://www.thorntontomasetti.com/sites/default/files/2022-08/TT-Arecibo-Forensic-Investigation-Report.pdf (hereafter “TT Final Report”), p. 12.

4 WJE Report, p. 43.

5 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 1.

6 G.J. Harrigan, A. Valinia, N. Trepal, P. Babuska, and V. Goyal, 2021, Arecibo Observatory Auxiliary M4N Socket Termination Failure Investigation, NASA/TM−20210017934, NESC-RP-20-01585, NASA Engineering and Safety Center, Langley Research Center, June, https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20210017934/downloads/20210017934%20FINAL.pdf (hereafter “NESC Report”), p. 100.

7 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 25.

8 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 26.

9 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 6.

10 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 8.

11 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 25.

12 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 3.

13 NESC Report, p. 99.

14 WJE Report, p. 34.

15 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 1.

16 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 2.

17 J. Abruzzo, L. Cao, and P. Ghisbain, 2022, “Arecibo Observatory: Stabilization Efforts and Forensic Investigation,” Thornton Tomassetti, Inc., presentation to the committee, February 17 (hereafter “TT presentation”), slide 34.

18 TT Final Report, Appendix J.

The highest instantaneous wind speed ever recorded at Arecibo Observatory is 110 mph and occurred as the eye of Hurricane Maria approached the site on September 20, 2017. While the hurricane caused widespread destruction in Puerto Rico, the only significant damage reported on the telescope was a failure of the line feed. However, because of the relatively short time between Hurricane Maria and the telescope’s first cable failure (August 10, 2020), it is natural to investigate the storm as a potential factor contributing to the collapse. Hurricane Maria is therefore used as a reference load throughout the analysis of the wind load effects.19

TT estimated Arecibo Telescope cable stresses from Hurricane Maria winds assuming a basic wind speed of 110 mph.20 It was estimated in the analysis that, based on an assumption of a 110-mph peak windspeed, the tension in the M4N cable increased 10 percent from the Maria wind loading. TT concluded, “Two recent extreme events—Hurricane Maria in 2017 and the January 2020 earthquake sequence—were specifically analyzed and estimated to have temporarily increased the cable tensions by up to 15 percent.”21 But even with the additional hurricane wind load, the analysis found the M4N cable to be the second (631 kips) most lightly loaded of all the auxiliary cables during Maria22 and was therefore calculated to have the highest safety factor (a tie with 2.1 “in hurricane conditions”) of any auxiliary cable on the Arecibo Telescope.23

SOURCE: J. Abruzzo, L. Cao, and P. Ghisbain, 2022, “Arecibo Observatory: Stabilization Efforts and Forensic Investigation,” Thornton Tomassetti, Inc., presentation to the committee, February 17, slide 34. Courtesy of Thornton Tomassetti, Inc.

___________________

19 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 1.

20 TT Final Report, Appendix J, p. 10.

21 TT Final Report, p. iii (unnumbered in the report).

22 TT Final Report, Appendix J, Figure 33, p. 35.

23 TT Final Report, Appendix J, Figure 34, p. 35.

POST-MARIA ARECIBO TELESCOPE INSPECTIONS

There exists significant uncertainty about what Arecibo Telescope damage was evident immediately post-Hurricane Maria. The Arecibo Telescope standard “Preventative Maintenance Report” provided by the National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center’s Arecibo Observatory (AO) for tower inspections comprises 10 “checkpoints” that are described and that are to be assessed by the observatory field staff.24 These include the following: “Task 006: Note condition of cables socket and saddles. Verify that saddle does not show cracks, are [sic] completely painted, and are not rusted. If you find something of the above listed items, report to the maintenance office through your supervisor” and “Task 008: examine each cable carefully looking for evidence of broken wires.”25 The July 20, 2018, Tower 4 maintenance record, the earliest post-Maria inspection report available to the committee, reports “OK” for Task 006 and “No Broken Wires” for Task 008.26

Box 2-1 summarizes maintenance inspection on Tower 4 from July 20, 2018, to July 6, 2020. These maintenance records also noted no broken wires, and all systems were “OK.”

Periodic inspections of the Arecibo Telescope’s cables before Maria failed to note any progressive increases in the pullout of zinc from the cable sockets on multiple auxiliary and main cables during multiple inspections, including the M4N-T auxiliary cable. Figure 2-3 shows the typical strand pull-out observed on the M4S-T socket in 2003 (approximately ½ inch pullout, left image) and for comparison, the M4N-T pullout after Maria in 2019 (approximately 1⅜ inch pullout, right image). Note that the white paint is visible on the cable, and the extruded zinc is visible in the 2003 image. According to the TT Final Report,27 the auxiliary cables were painted in 1995 and 2003. A comparison of the 2003 image with the picture from 2019 clearly shows significant additional pullout post-Maria. There are no images of this socket available from the inspections performed in 2018. The presence of a large area of unpainted zinc near the socket in the image from 2019 is a clear indication of major socket deterioration. The clear movement, or slip, of the cable at the zinc anchorages, no matter what the cause might be, should have been seen as a degradation mechanism in a key structural component whose failure would be catastrophic. It should have raised serious concerns about the condition of this and other cables, but there was no mention of such anomalies anywhere in the inspection reports.

As the zinc extrudes through the front of the socket, it is expected that a void or voids would appear somewhere within the socket (typically at the cap under the mastic coating) that can create a depression on the top of the socket. An example showing these depressions for sockets on the M4 tower end sockets is shown in Figure 2-4. This type of depression could have been noted by inspectors as an important clue as to the condition of zinc in the socket.

Additional significant increases in post-Maria socket pullout should have been considered a clear and unambiguous warning sign of a growing danger of catastrophic failure long before the failure of the auxiliary cable socket M4N-T.

Conclusion: The Arecibo Telescope operators would have benefited from more detailed engineering or structural risk guidance concerning inspection protocol, documentation, and/or indicators of structural deterioration and unexpected performance.

There was no documentation found by the committee of any immediate post-hurricane systematic inspections or loading analyses of the Arecibo Telescope’s structural cables or socket connections beyond what was cited previously from the maintenance inspection reports. A structural analysis of the loads imposed on offshore structures subjected to a major (design level) hurricane event is required to demonstrate fit for purpose before putting it back into operation. TT observed,

___________________

24 A. VanderLey, 2022, “Arecibo Observatory: Failure Event Sequence,” National Science Foundation presentation to the committee January 25 (hereafter “NSF presentation”), slide 50.

25 NSF presentation.

26 NSF presentation.

27 TT Final Report, Appendix D, p. 2.

BOX 2-1

Preventative Maintenance Records: Tower 4 for July 20, 2018, to July 6, 2020

- July 20, 2018 (Monthly)

- September 19–20, 2018 (Monthly)

- October 24, 2018 (Monthly)

- November 21, 2018 (Monthly) Noted Towers 4 and 12 inspected for the possibility of a robot to clean and paint the cables; robot could not pass past the dampers on the cables.

- January 9, 2019 (Monthly) Noted all in normal conditions.

- February 25, 2019 (Monthly) Noted all in normal conditions (subsequently more information available; see NESC/WJE report).

- March 12, 2019 (Monthly) 4.8 mag earthquake in Salinas PR at 9:08 AM. Noted inspection of tower, stairs, saddle, cable sockets and cables. Noted all in normal conditions.

- April 22, 2019 (Monthly) Tower inspected and safety lines measured for replacement. No other notes.

- May 16–21, 2019 (Monthly) New safety line installation project.

- July 31, 2019 (Monthly) Notes of maintenance activity unrelated to socket.

- August 29, 2019 (Monthly) Routine inspection to all three towers due to Hurricane Dorian. No impact from Hurricane, no findings.

- September 23–25, 2019 (Earthquake inspection) Two strong earthquakes noted at 6.0 and 5.1 mag at 11:35 am on 23 Sept 2019 were felt. Inspections to all three towers took place on 25 Sept 2019, no damages. On 24 Sep 2019, AO was in lockdown due to storm Karen. No damages from Karen.

- September 27, 2019 (Monthly) Notes: Two strong earthquakes 6.0 and 5.1 @11:35am 9/23/2019 were felt. Inspections to all three towers took place on 9/25/19, no damages. A measurement scale was installed to the socket/cable Auxiliary 4 to monitor any movements. Inspected tower and noted that all the cables and the saddle were painted.

- November 14, 2019 (Monthly)

- December 28, 2019 (Monthly) Two strong earthquakes took place in Guanica (mag 4.8 at 6:00 pm and mag 5.1 at 9 pm). No damages noted.

- January 6–27, 2020 Pictures noted to have been taken of the cable socket and saddles. No damage to the structure noted.

- February 4–5, 2020 Another mag 5.0 earthquake in Guanica noted at 10:30 am. Inspections to all towers noted (This was the week a structural engineer was on site).

- May 1–3, 2020 Inspections by drone due to COVID after 4.8 and 4.5 mag earthquakes were felt at AO.

- June 4–5, 2020 Earthquakes noted (mag 4.4 and 4.6 mag); inspections were performed by drone.

- July 3-6, 2020 Noted strong Earthquakes of mag 5.1; all observations were stopped. Inspections by platform personnel was [sic] performed. No damages [sic] were found.”

SOURCE: A. VanderLey, 2022, “Arecibo Observatory: Failure Event Sequence,” National Science Foundation presentation to the committee, January 25, slides 51–52.

After Hurricane Maria in 2017, the Observatory staff observed and recorded cable slips of more than 1 inch on two of the sockets. There is no documentation to show whether these cable slips increased during the hurricane, and to our knowledge, they were not identified as an immediate structural integrity issue.28

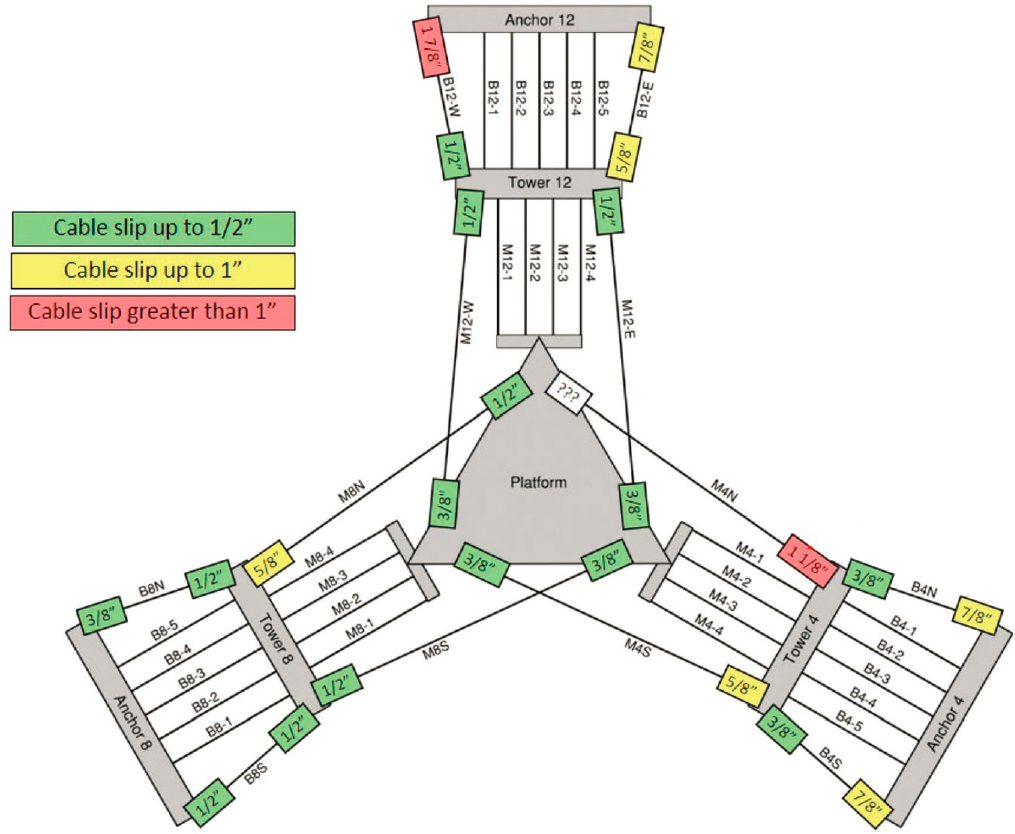

The committee concurs and has found no evidence to the contrary. TT concluded that, just before the M4N-T failure, three of the six tower-end auxiliary cable sockets had a pullout of greater than ½ inch, and seven cables total had a pullout greater than ½ inch.29 Even with these pullouts, TT was still assigning a safety factor of 2.0 or

___________________

28 TT Final Report, p. ii.

29 TT Final Report, Figure 25, p. 18.

SOURCES: G.J. Harrigan, A. Valinia, N. Trepal, P. Babuska, and V. Goyal, 2021, Arecibo Observatory Auxiliary M4N Socket Termination Failure Investigation, NASA/TM−20210017934, NESC-RP-20-01585, NASA Engineering and Safety Center, Langley Research Center, June 15, https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20210017934/downloads/20210017934%20FINAL.pdf, Figure 6.4-2. Left: Photo from Ammann & Whitney, NAIC Cornell University, Arecibo Radio Telescope, Structural Condition Survey 2003, courtesy of Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. Right: Photo from NAIC Arecibo Observatory, a facility of the National Science Foundation.

greater, which assumes zero strength degradation from creep or any other aging mechanism, to every socket with these largest cable extensions before the M4N failure.30 This suggests that it was not recognized that material degradation modes such as creep can operate at a fraction of the cable’s strength.31

The limited post-Maria cable socket pullout documentation is sparse. “Cable slips were observed but not consistently monitored and reported before August 2020.”32 The earliest known documentation of the post-Maria cable slip was a May 15, 2018, measurement of at least 1.5 inches of pullout at B12W-G, more than 6 months

___________________

30 TT Final Report.

31 Moreover, the connection between vulnerability to creep induced wire failure and pullout length is likely very complicated due to nuances in zinc seating, location of the crown of compression inside the socket and likely there cannot be assumed to be a direct proportionality between creep pullout as an absolute length and eventual socket failure.

32 TT Final Report, p. 17.

SOURCE: Thornton Tomasetti, 2021, Arecibo Telescope Collapse: Forensic Investigation Interim Report, NN20209, prepared by J. Abruzzo and L. Cao, November 2; photo from NAIC Arecibo Observatory, a facility of the National Science Foundation.

after Hurricane Maria.33 The last known cable slip documentation of socket M4N-T of (1.125 inches), where the first cable failure occurred, was observed on February 19, 2019,34 more than 18 months after the hurricane but still more than 18 months before the failure. The observed slip of M4N-T was now at least one-third of the cable’s diameter in 2019. “The inspection process did not couple the qualification/design process to a pass/fail criterion to trigger a replacement. Data were not provided to explain the decision process after the 2019 photos were taken.”35 The committee concurs with both these conclusions.

Finding: Despite the dramatic pullout at multiple connections recorded by the AO field staff post-Maria, no additional concern about the evident structural distress was noted in the in-house or external inspections, and no action was undertaken to address it.

On February 18, 2019, photographs of auxiliary cable sockets on Towers 4, 8, and 12 documented the tower auxiliary socket pullout on all three towers.36 Still, no inspection resulted in an emergency cease of operations due to concerns about the structural integrity of the facility. The reports from these inspections stated, “no structural damage noted.” The structure clearly exhibited evidence of socket slip and wire breakage, but the structural damage in many cases was hidden and not assessable by visual observation. WJE noted, “In-service inspections showed evidence of progressive zinc extrusion on several Arecibo sockets, which in hindsight was evidence of cumulative damage and, in effect, a missed opportunity to prevent cable failure.”37

Finding: The routine inspection form used by the AO field staff did not include instructions for socket inspection.

___________________

33 TT Final Report.

34 TT Final Report.

35 NESC Report, pp. 114–115.

36 TT Final Report, Appendix D, pp. 14–18.

37 WJE Report, p. 11.

TT eventually concluded,

Cable slips were observed on the auxiliary sockets of the Telescope structure, and an increased amount of slip was observed on some auxiliary sockets within the past 2 years before the first cable failure. The cable slips were evidence of structural distress in the sockets [not governed by engineering safety factors related to cable strength divided by load] and should have raised a concern that cables may fail.38

NASA concluded, “In-service inspections showed evidence of progressive zinc extrusion on several Arecibo sockets, which in hindsight indicated significant cumulative damage.”

Zinc pullout at a socket front meant that voids or depressions would necessarily appear either inside the socket (hidden voids) or on the socket back end (visible depressions). These depressions were never noted in any of the inspections, even though pictures show depressions forming on the back ends of several cable sockets (on both auxiliary and main cables) after the first cable failure. Cable pullout as a sign of growing socket distress was not recognized by either staff or contracted structural engineers.

Further cable pullout was not evident in the limited photographic evidence taken before and after the January 2020 earthquakes.39 The M4N cable was predicted to be the second most lightly loaded auxiliary cable in the earthquake.40

Initial report (January 27, 2020) noted damage to vibration dampers, tie-down blocks and slabs, potential for cracked platform steel components, and cracks in concrete buildings. Also, concerns were noted about site power infrastructure, the need for more safety and inspection equipment, and structural analysis and modeling for resiliency. [A] $3.325 million proposal submitted in 2020 and awarded included tasks for acquisition and installation of new vibration dampers to reduce vibration caused by external forces (wind or seismic events).41

The best available information on the distribution of the Arecibo Telescope’s socket pullouts just before the M4N-T socket failure is summarized in Figure 2-5.42

Conclusion: The Arecibo Telescope’s failure sequence began with Hurricane Maria.

THE HURRICANE MARIA AFTERMATH

The first evidence of additional cable socket slippage after the 2011 A&W survey was documented by Arecibo staff in 2019, more than 2 years after Hurricane Maria. The 3 or so years after Maria and before the Arecibo Telescope’s collapse were occupied with repair planning, proposal writing, cost justifications, and administrative activity unrelated to the cables that failed.43

Ray Lugo of the University of Central Florida (UCF), and former director of UCF’s Florida Space Institute and principal investigator for the National Science Foundation (NSF) operations grant of the AO, told the committee that he inspected the facility post-Maria as part of the handover to UCF: “I have used wire ropes and socketed cables lifting devices, and in my experience as an engineer, I’d never seen a cable, a socketed cable, with that amount of pull-through. I was told that it had been reviewed by an external engineer, and that there was not any real concern about cable failure.”44 NSF has reported that it does not have a record of this exchange. The consultants failed to notice or recognize the critical importance of the socket cable pullout or even the importance of immediately

___________________

38 TT Final Report, p. 25.

39 TT Final Report, Appendix D, pp. 16–17.

40 TT Final Report, Appendix K, p. 9.

41 NSF presentation, slide 20.

42 TT presentation, slide 28.

43 R. Lugo and F. Cordova, 2022, “Perspectives on Grant Award and Operations of Arecibo Observatory Cooperative Agreement by the University of Central Florida,” University of Central Florida (UCF) presentation to the committee, February 17 (hereafter “UCF presentation”), meeting transcript minutes 00:09:58 to 00:21:54.

44 UCF presentation, meeting transcript minute 00:08:46.

SOURCE: J. Abruzzo, L. Cao, and P. Ghisbain, 2022, “Arecibo Observatory: Stabilization Efforts and Forensic Investigation,” Thornton Tomassetti, Inc., presentation to the committee, February 17, slide 28; courtesy of Thornton Tomassetti, Inc.

inspecting for cable and socket connection damage post-Maria, except for wire breaks. NSF has told the committee that “at no time during the review of damage post-Maria was increasing socket slippage ever brought to NSF’s attention as one of the issues to be considered for further inspection, analysis or in need of a repair.”

Conclusion: The unexplained significant cable socket pullouts should have alerted the consultants that assumptions about remaining cable strength based on initial design safety factors were likely no longer appropriate.

The AO’s working conditions in the last months of 2017, immediately post-Maria, and during the last months of SRI’s facility management were difficult. During the preparation of proposals for the repair of the telescope, as well as the operational transition between SRI and UCF, Ray Lugo noted that power was not fully restored until sometime in December 2017.

We couldn’t even access the platform because the catwalk had been significantly damaged, and that’s the way to go up to the platform. Then we spent some time having to repair the cable car, which is the only other way of going up

into the platform. At that time, getting materials and communicating to purchase anything was, was impossible. So, it really took several months [and] it was really more visual inspections of whatever could be accessed.45

We didn’t even write the [repair] proposal until … the June timeframe of 2018.46

The catwalk repair was part of the $2 million time-critical repairs immediately following Hurricane Maria.47 It should be noted that the committee did not receive a presentation from the previous operator, SRI.

The M4N-T socket slip warning sign was finally photographed in 2019 but not heeded in the subsequent 1½ years it took for this tower connection to fail. As cited previously, this cable was not under suspicion or slated for replacement. Even after the M4N-T socket failed, Ray Lugo told the committee that he reached out to WSP Global, Inc., who told him after some “calculations” that “yes, we [the Arecibo Telescope] still had a positive factor of safety, less than two, but, I think it was like 1.7 or 1.8.”48 Since the committee was not afforded an opportunity to meet with representation from the firm, the committee does not know if engineers at WSP did not observe the socket pull-out warning signs or noted them but dismissed them as being unimportant. Ray Lugo also told the committee, “[AO] tasked Thornton Tomasetti to come up with a structural model that we could use to analyze the structure. And as a result, it actually did confirm what WSP gave us. While we were not at a 2.0 or a greater than 2.0 factor of safety, we were still greater than, I think, 1.7.”

Conclusion: All of WSP’s and TT’s calculated safety factors appear to be incorrectly based on the nominal cable design strength without consideration given to intervening degradation mechanisms and damage mechanics, which are highly time-dependent and had unknown implications.

BUREAUCRATIC DELAYS IN FUNDING ARECIBO TELESCOPE HURRICANE REPAIRS

As reflected in the post-Maria timeline, there were various administrative events occurring at the Arecibo Telescope in the process of trying to repair the hurricane damage during a change of Arecibo Telescope operators. NSF was changing contract operators from an SRI-led consortium to a UCF-led consortium months after Maria hit in September 2017.49 While the managing organization changed, “a majority of staff (including director of facility) remained the same at the Observatory.”50

Unfortunately, the planned post-Maria repairs of the Arecibo Telescope’s structural components were technically misdirected toward components and replacement of a main cable that ultimately never failed.51 Thus, none of the specified repairs would have forestalled the Arecibo Telescope’s collapse, even if completed in a timely manner. NSF awarded $2 million to complete the most critical, time-critical repairs after Hurricane Maria.52 Cable replacement was not identified as “time-critical.” A larger repair program, including the Tower 8 main cable replacement, were not identified “to be an issue.”53 A more detailed inspection and review of the Arecibo Telescope’s structural condition immediately following Hurricane Maria might have identified the measurable socket degradation leading to critical repair or stabilization.

The repair process—planning, proposal preparation, justification for repair scope and costs, NSF’s examination and funding, and the planned execution—for these non-urgent items remained incomplete by the time the telescope failed 38 months later.54 Ray Lugo described to the committee how months of his time during 2018 were spent

___________________

45 UCF presentation, meeting transcript minute 00:29:50.

46 UCF presentation, meeting transcript minute 00:27:05.

47 NSF presentation, slide 12.

48 UCF presentation, meeting transcript minute 31:56.

49 TT Final Report, p. 2.

50 NSF presentation, slide 9.

51 NSF presentation, slide 15.

52 NSF presentation, slide 12.

53 NSF presentation, slide 21.

54 NSF presentation, slide 14.

writing, resubmitting, and justifying repair funding proposals.55 Repairs had to go through the traditional “bid and proposal” process, described in more detail below, which added years of delay.56

The initial funding for the Arecibo Telescope’s post-Maria most time-critical repairs was not awarded until nine months after Maria. The first hurricane repair award of $2 million was made to UCF in the summer of 2018.57 The eventual congressional appropriation of $14.3 million for the AO included a large number of non-critical items “restoring AO to world-class scientific capabilities.”58 The most time-sensitive were further prioritized in the first $2 million award made to UCF on June 1, 2018.59 The most time-critical repairs included cable replacement analysis and design, but not cable repair or replacement. Cable replacement was not identified as time-critical.60 Almost another year later, in the Spring of 2019, NSF held a merit review panel for a proposal for the remaining $12.3 million repairs to restore the telescope, which included structural engineers to assess the main cable replacement.61 NSF then required a detailed project execution plan and detailed plans for the cable replacement, to be put together by Louis Berger, as well as a request for proposal for the work. Next, NSF submitted a waiver to the Office of Management and Budget to permit $11.3 million of $14.3 million to be spent over 60 months instead of 24 months, which “would permit time for careful evaluation and design of repairs.”62 In the summer of 2019, almost 2 years after Maria, $12.3 million (to be spent on a timeline through fiscal year 2023) was awarded to UCF to complete 14 prioritized tasks in the short term, none of which involved Tower 4 cable repair or replacement (the tower where all the cable failures occurred), only the planned Tower 8 spliced main cable replacement. The Tower 8 main cable was the only cable-related repair noted in post-Maria evaluation and funding requests, as the project execution plan prioritized replacing the spliced cable as the highest risk. Structural analysis, main cable replacement design, and assistance in the cable replacement and construction administration was to be overseen by WSP (who acquired Louis Berger, who acquired A&W).63

“NSF was informed that the WSP structural engineers visited the site in February 2020 to work on the spliced main cable replacement, and they performed inspection of the towers, cables, and platform primary structural elements while there, but no additional damage was noted during those inspections.”64 NSF reported that it does not have any evidence that WSP looked specifically at socket “pullouts.” NSF told the committee that its documentation simply states that WSP completed a “thorough structural analysis.”65 As part of its post-Maria repair proposal to Felipe Soberal, director, operations and maintenance of the AO, Michael Urbach of WSP (formerly Louis Berger) did propose to review “anchorage slip conditions,”66 but it does not appear this proposal was accepted. The committee was not afforded an opportunity to question WSP.

Conclusion: Analysis performed by consultants in response to expressed concerns was incorrect. The consultants did not identify the key socket failure risk following Hurricane Maria, and none of the proposed repairs would have saved the Arecibo Telescope from collapse.

Finding: Only after the first socket failure did the consultants focus technical attention on the cable sockets, but even then, failed to consider the degradation mechanisms of the sockets. By the time a socket failed, there remained only a few months to respond.

___________________

55 UCF presentation, meeting transcript minutes 19:34 to 24:09.

56 NSF presentation, slide 13.

57 NSF presentation, slide 12.

58 NSF presentation, slide 10.

59 NSF presentation, slide 12.

60 NSF presentation.

61 NSF presentation, slide 13.

62 NSF presentation.

63 NSF presentation, slide 15.

64 NSF presentation, slide 21.

65 NSF presentation, slide 21.

66 Letter to Felipe O. Soberal from Michael Urbach of Louis Berger, March 4, 2019, p. 2.

SEQUENCE OF CABLE FAILURE EVENTS

First Cable Socket Failure: M4N-T

The M4N-T cable failure occurred when the M4N-T AUX socket pulled out on August 10, 2020. At the time of the M4N-T cable socket failure, it was reported that the “telescope was operating normally”67 in the early morning under good conditions, dead calm, and no new warning indicators right up to the moment of failure. Without such a warning, and had this failure occurred during normal working hours, there could have been serious injuries and even loss of life during the collapse.

Right up to the time of the M4N-T cable socket failure, even with 1.125 inches of pullout, the cable’s safety factor was incorrectly assessed to be ~2.2.68 At the time of the M4N cable failure, it was not the most heavily loaded auxiliary cable.69 As noted earlier, during Maria, the analysis predicted that M4N was one of the more lightly hurricane-loaded auxiliary cables, and M8N was the least loaded. The calculated cable safety factors gave no consideration to degradation mechanisms.

Although one cable stabilization had been planned as part of the hurricane repair appropriation, it was not for the M4N cable that ultimately pulled loose. Stabilization with a friction clamp for the B12W-G backstay cable on Tower 12 was set to begin almost 3 months later, on November 9, 2020.70

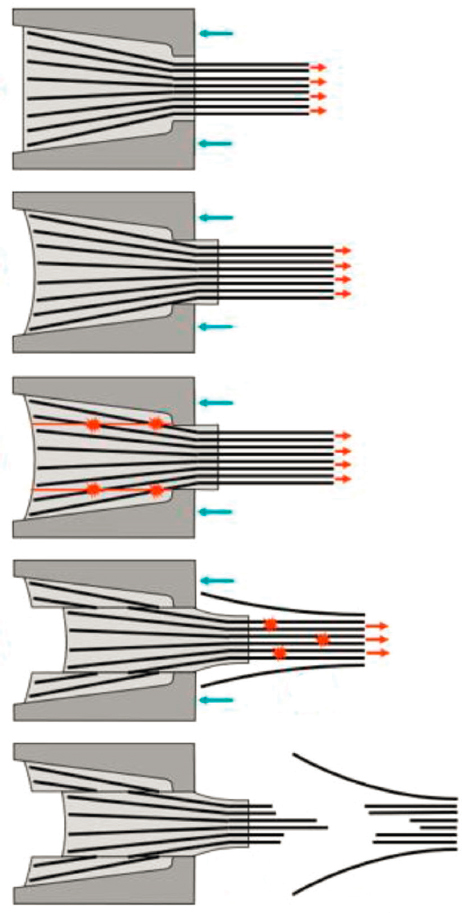

The M4N-T failure is illustrated in Figure 2-6.71 Zinc creep in the less constrained central “core” of the wire “broom” allowed the cable load to be slowly transferred to the outer wires of the broom. The outer wires of the broom begin to fail in overload. Each outer wire failure transfers incrementally more load to the remaining outer wires. Eventually, all but 1 of the 56 wires that failed were in the outer three rows of the cable.72 Ultimately, “forty-four of the 56 wire fracture morphologies were cup-cone fractures, nine were shear, and the remaining three were mixed-mode fractures, which included a progressive failure mechanism believed to be hydrogen assisted cracking, or HAC (one cup-cone/HAC and two shear/HAC).”73 The broom’s center pulled out of the socket, and the M4N-T cable socket failed.

Between the M4N failure on August 10, 2020, and the M4-4 failure on November 6, 2020, AO staff inspected the structure regularly.74 Inspection photographs were taken periodically of cable pullout of Sockets M4S-T, M8N-T, M12E-T, M12W-T, B4N-T, B4S-T, B8N-T, B8S-T, B12E-T, and B12W-T.75 Immediately after the failure, four wires on M4-1 broke.76 The failed M4N-T socket was removed from Tower 4 on September 23, 2020. Emergency stabilization plans were approved by the end of September 2020.77

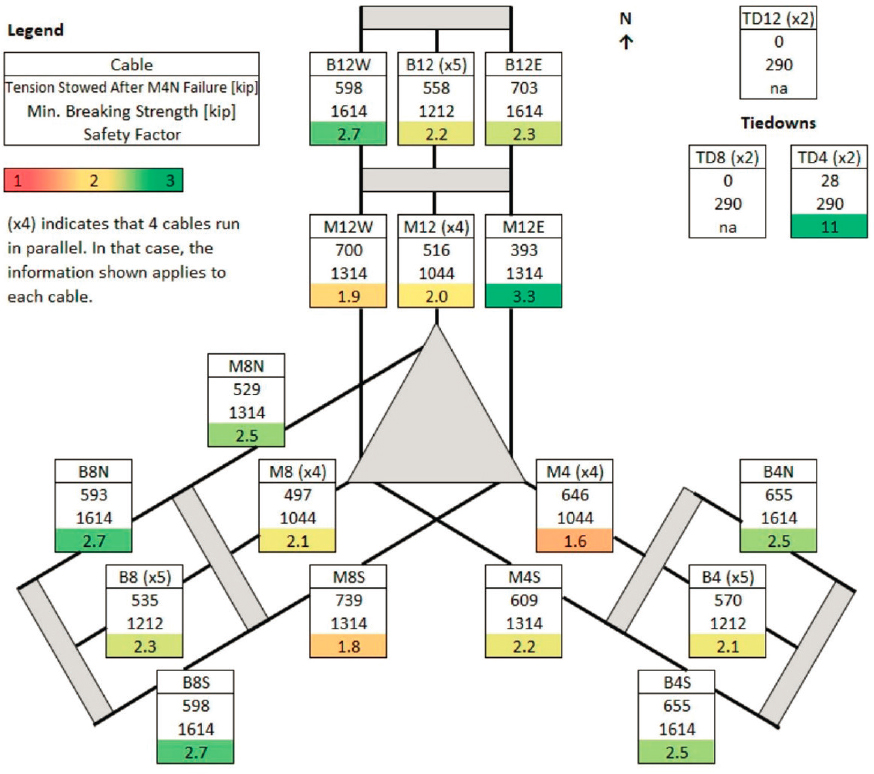

The emergency repair proposal for stabilization was submitted on October 19 and evaluated until October 23 by NSF, Sabal Engineering, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.78 Even after the M4N-T failure illustrated how the remaining strength of the Arecibo Telescope’s cable spelter sockets had been vastly overestimated, no consideration was given to the potential strength degradation of the other cables. Because the cable’s original design strength was used in the calculations, and there was no consideration given to degradation, the safety factor of the M4-4 and M4-2 cables was still assumed to be 1.679 after the telescope had been stowed. TT concluded “that M4N carried a tension of 600 kips when it failed.”80 But TT assumed M4N’s strength was the original undegraded 1,314

___________________

67 TT Final Report, p. 13.

68 TT Final Report, p. 18.

69 TT Final Report, Figure 40, p. 29.

70 NSF, “Report on the Arecibo Observatory, Arecibo Puerto Rico Required by the Explanatory Statement Accompanying H.R. 133, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021,” https://www.nsf.gov/news/reports/AreciboReportFINAL-Protected_508.pdf, accessed June 1, 2023, pp. 1–2.

71 TT Final Report, Figure 25, p. 25.

72 NESC Report, p. 26.

73 NESC Report, p. 41.

74 TT Final Report, Appendix E, p. 4.

75 TT Final Report, Appendix D, pp. 15–24.

76 TT Final Report, Appendix E.

77 NSF presentation, slide 31.

78 NSF presentation.

79 TT Final Report, Table 4, p. 32.

80 TT Final Report, Appendix G, p. 11.

SOURCE: Thornton Tomasetti, 2022, Arecibo Telescope Collapse: Forensic Investigation, NN20209, prepared by J. Abruzzo, L. Cao, and P.E. Pierre Ghisbain, July 25, https://www.thorntontomasetti.com/sites/default/files/2022-08/TT-Arecibo-Forensic-Investigation-Report.pdf; courtesy of Thornton Tomasetti.

kips, giving it a safety factor of 2.2.81 M4N-T’s unanticipated failure illustrated that the safety factor calculated for the socket was inaccurate.

Even after the unanticipated failure of M4N at less than half its assumed strength rating, “up until November 6 [the] assessment, structural modeling, observations led to assessment that structure was stable enough for further stabilization work to proceed aided by additional monitoring devices, regular drone inspections, work safety plans, etc.”82 The assumptions made about the Arecibo Telescope’s remaining cable strength after the M4N failure are summarized in Figure 2-7.83 No consideration appears to have been given to any degradation mechanisms.

___________________

81 TT Final Report, Appendix G, Figure 15, p. 12.

82 NSF presentation, slide 33.

83 TT Final Report, Appendix G, Figure 21, p. 16.

SOURCE: Thornton Tomasetti, 2022, Arecibo Telescope Collapse: Forensic Investigation, NN20209, prepared by J. Abruzzo, L. Cao, and P.E. Pierre Ghisbain, July 25, https://www.thorntontomasetti.com/sites/default/files/2022-08/TT-Arecibo-Forensic-Investigation-Report.pdf; courtesy of Thornton Tomasetti.

After the M4N-T failure, the main cables to Tower 4, M4 (×4) became loaded to 646 kips (the highest service load they had ever borne in 57 years)84 compared to 516 kips in the M12 (×4) mains and 497 kips in the M8 (×4) mains, as illustrated in Figure 2-7. This reduced the TT computed (but incorrect) safety factor to 1.6, even with the telescope stowed because of the increased load.85 However, the safety factor was actually near 1.0 because of a decreased cable strength at this load. This decrease in cable strength was due to hidden outer wire failures, which had already fractured due to shear stress from zinc pullout.

Second Cable Socket Failure: M4-4T

The tower end socket of M4-4 failed on November 6, 2020, and the failure sequence is illustrated in Figure 2-8.86 TT’s analysis calculated that there was 646 kips of load in this main cable at the time of failure, which had

___________________

84 TT Final Report, Appendix C, Table 1, p. 3.

85 TT Final Report, Appendix G, Figure 20, p. 16

86 TT Final Report, Figure 25, p. 25.

SOURCE: Thornton Tomasetti, 2022, Arecibo Telescope Collapse: Forensic Investigation, NN20209, prepared by J. Abruzzo, L. Cao, and P.E. Pierre Ghisbain, July 25, https://www.thorntontomasetti.com/sites/default/files/2022-08/TT-Arecibo-Forensic-Investigation-Report.pdf; courtesy of Thornton Tomasetti.

a nominally rated strength of 1,044 kips. The wire failed in the socket first, causing the core to displace, which led to overstress conditions in the cable wires outside the socket, causing total cable rupture.87

After the failures of the M4N-T and the M4-4T socket connections illustrated the remaining strength in the Arecibo Telescope’s spelter sockets, the calculated value of the M4-2 cable safety factor was reported to be 1.3 in TT’s 2021 Arecibo Telescope Collapse: Forensic Investigation Interim Report.88 However, “this cable broke under conditions that should have been well within its support capabilities, indicating that it, along with the remaining main cables, may have been weaker than expected.”89 “[The] cable failed below its expected capacity, making it impossible for engineers to determine stability of structure (cable that failed was designed for 1,044 kips; was expected to hold 1,044 kips, but failed at 614 kips).”90 TT, the Engineer of Record, advised NSF that another cable failure would be catastrophic. NSF determined that a “controlled decommissioning of the telescope” should begin.91

Final Cable Failure: M4-2T

The socket on the tower end of the M4-2 cable failed, and the Arecibo Telescope collapsed on December 1, 2020. According to TT,

Between M4-4 Failure and Collapse (November 6, 2020, and December 1, 2020), the failure of M4-4 on November 6, 2020, caused multiple new wire breaks in the remaining M4 cables: three breaks at the tower end of M4-1, a break at the tower end on M4-2, and four breaks at the platform end of M4-2. No change was observed on the remaining tower sockets.92

M4-2 failed at its socket at the top of Tower 4 and was followed by the failure of the remaining two main cables. The suspended structure subsequently collapsed and the tops of all three towers then broke off. A drone “video shows a wire break on M4-2, followed by the entire cable failure 3 seconds later and the failure of the remaining two M4 cables immediately after.”93

___________________

87 TT Final Report, Appendix G, Figure 21, p. 16.

88 TT, 2021, Arecibo Telescope Collapse: Forensic Investigation Interim Report, NN20209, prepared by J. Abruzzo and L. Cao, November 2 (hereafter “TT Interim Report”), p. 14.

89 NSF presentation, slide 37.

90 NSF, 2021, “Report on the Arecibo Observatory.”

91 NSF, 2021, “Report on the Arecibo Observatory,” pp. 2–3.

92 TT Interim Report, p. 25.

93 TT Final Report, p. 20.