Equity in K-12 STEM Education: Framing Decisions for the Future (2025)

Chapter: 7 Learning in STEM

7

Learning in STEM

The way classrooms and schools are organized for learning in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) is often informed by outdated and problematic assumptions about learning and learners. These assumptions can lead to inequitable pedagogical approaches, narrow conceptions of what proficiency in STEM disciplines looks like, and negative judgments about children and youth who come from communities that are not white and middle or upper class. Recent research-based insights about learning, however, provide new lenses for thinking about learners and how they can and should engage with STEM. They also clarify the processes by which negative experiences in STEM classrooms can alienate students and undermine their success. Taken together, these insights suggest ways of reorganizing learning experiences, instruction, and other structures of schools to maximize the potential of learners and open up STEM in ways that promote more equitable learning.

In this chapter, we begin by first articulating some perspectives around learning that have negatively shaped the current educational system to show how they have contributed to perpetuating inequity. We then turn to a discussion of current research on human learning that reveals how learning is situated within sets of relationships that are embedded in cultural contexts. Through social interactions and engagement across settings, individuals develop ways of knowing, relating, and being that shape how they engage with STEM in school and how they see themselves in relation to STEM. These insights into the sociocultural dimensions of learning prompt a reevaluation of current approaches to instruction, curriculum, and students’ pathways, topics taken up in subsequent chapters. In combination with the

equity frames articulated in Chapter 6, they can illuminate concrete steps that educators and education leaders can take to begin to reimagine STEM education and dismantle existing structural inequities. These steps are discussed in greater detail across Chapters 8–11.

DEFICIT PERSPECTIVES AND LEARNING IN SCHOOL

The theories of culture and learning highlighted in this chapter are critical responses to and visions beyond a long history of deficit ideologies in the field of education. Such ideologies have long shaped education policy, design, research, and practice, and have perpetuated inequity in myriad ways. Historicized definitions and understandings of deficit thinking are crucial to addressing and changing this pervasive way of thinking and promote equity in STEM education.

Deficit perspectives, the deficit model, or deficit thinking are all different terms that are used to capture a perspective that centers on what is “lacking” with respect to what has been deemed the “norm and standard.” Deficit thinking refers to the ways cultural differences are framed as deficits or deviations from presumed universal pathways constructed based on studies that have primarily focused on white, educated, industrial, rich, democratic populations, particularly white, middle-class families (Henrich et al., 2010; Lee, 2009). Deficit ideologies situate this presumed “lack” as a trait or condition for which an individual has sole responsibility, and therefore advocate fixing the individual. Historically and today, deficit perspectives treat cultural variation as a deviation from Western norms of human behavior and cognition, thereby projecting conceptions of deficiency across non-Western or non-dominant communities and privileging singular pathways of learning (Vossoughi et al., 2021).

Deficit perspectives have long shaped many aspects of formal schooling in this country (see Chapter 2 for a discussion of early American practices and policies). During the 1960s and 1970s, a time corresponding with the Civil Rights Movement, the War on Poverty, and associated legislation, deficit thinking was evident in the common usage of language of cultural deprivation, culture of poverty, and cultural or social disadvantage, with the absence of demonstrated Eurocentric, white, middle-class values, and norms characterized as a deviation from the norm and a deficiency to be remedied (Gordon, 1965). The view was promulgated in policy circles by aspects of the Moynihan (1965) report, a policy document written during the Johnson administration that characterized poverty in Black communities as the result of deprived and depraved cultural values. This dominant perspective went on to permeate educational research, including research in STEM (see Box 7-1 for a discussion of how research can and has perpetuated deficit

BOX 7-1

How Research on Learning and Academic Achievement Has Reinforced Deficit Perspectives

Deficit theories have been reinforced by research that employs experimental designs that use decontextualized tasks and the absence of expected responses to confirm hypotheses about children’s linguistic and cognitive deficiencies (Cole, 2013; Labov, 1970; McDermott & Vossoughi, 2020; Vossoughi et al., 2021). Langer-Osuna and Nasir (2016) show how a study that claimed to illustrate Mexican American students’ negative attitudes toward education (Demos, 1962) based its findings on five survey items that specifically asked students to assess the helpfulness of school staff and teachers. Students’ genuine experiences and critiques of school structures were used to cast the students as deficient, in a patterned move many have named “blaming the victim” (Lave, 1996; Valencia, 1997).

Critiques of deficit thinking highlight the persistent methodological biases in studies that draw negative conclusions about children’s linguistic and cognitive competence based on flawed experimental designs and inadequate attention to alternate hypotheses (Valencia, 1997; Vossoughi et al., 2021). Ecologically valid research (studies where findings can be more readily generalized to real-world contexts), in contrast, carefully examines the implicit and explicit perspectives and assumptions of research, and calibrates instruments and findings with local contexts and meanings (Cole et al., 1978; Medin & Bang, 2014). For example, high-stakes and asymmetrical interview conditions where Black and Indigenous children astutely said as little as possible, lest it be used against them, were used to draw conclusions about their lack of linguistic competence. These same children were shown to be highly adept language users under conditions that ensured ecological validity and psychological safety (Labov, 1970; Vossoughi et al., 2021; Washinawatok et al. 2017).

Challenging deficit thinking requires units of analysis (ways of constructing or modeling the phenomena under study) that move beyond the individual and attend to the cultural tools, sources of pedagogical and social support, forms of psychological safety and belonging, valued ways of knowing and being, and access to resources and opportunities that mediate students’ educational experiences. Expanding the unit of analysis widens the focus of intervention from individuals to environments and systems (Artiles, 2017; Diaz & Flores, 2001; Marin, 2020; McDermott et al., 2006; Vossoughi et al., 2020).

perspectives). The legacy of these and similar approaches is still evident today.

In the early 1980s, the report A Nation at Risk signaled a need for educational reform and a push for higher, more rigorous standards. The report garnered broad attention and not only initiated a movement focused on standards, but also fueled the labeling of students as “at risk” of not meeting the more rigorous standards and encouraged a deficit positioning of students (Goldberg & Harvey, 1983). The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) further foregrounded standards as it focused on achievement

as measured by standardized tests and promoted the disaggregation of achievement results by demographics as an accountability measure. (For more on both A Nation at Risk and NCLB, see Chapter 2.) NCLB furthered the use of deficit language in the education canon with terms like “achievement gap,” used to convey differences in group outcomes. The term insinuates that achievement outcomes, narrowly defined, are solely due to individual factors and does not consider structural and systemic inequality and inequity and the accumulative effect of each over time (Ladson-Billings, 2006).

Deficit thinking interprets differential outcomes on standardized tests as failures of individual students that reflect larger cultural practices, values, and attitudes toward achievement within poor and minoritized families and communities. This perspective leads to interventions and policies designed to compensate, remediate, and “fix” presumed deficits within individual students. The deficit stance typically fails to inquire into external and structural factors, such as inequities in schooling policies and practices (Langer-Osuna & Nasir, 2016; Valencia, 1997). Nor does it interrogate the narrow and culturally biased measures used to assess learning (Au, 2009). (See Chapter 4 for a discussion of problems with assessments.) Deficit thinking leads to experiences of institutional stigmatization and stress for students, who must learn to navigate pathologizing assumptions regarding race, poverty, language variation, gender, and disability (Nasir et al., 2006). Students themselves come to be known as problems rather than members of a population experiencing problems within and sometimes because of the educational system (Gutiérrez et al., 2009).

In considering the equity frames described in Chapter 6, deficit thinking is likely to be associated with focusing mainly on Frame 1 (reducing gaps between groups). An approach that attends primarily to gaps will likely focus on locating the problem and the solution within individual students rather than systemic or other external factors. Or it may implicitly, or even explicitly, assume that existing gaps are due to deficiencies with particular groups of people that lack something or have “dysfunctional” ways of operating in the world that need to be changed in order for them to be successful. Even within Frame 2 (expanding opportunity and access), which includes attention to more structural issues (for example, course offerings or availability of enrichments programs), a deficit perspective may bring with it the implicit assumption that some learners need opportunities so that they can obtain something they are lacking, or so that they can adopt “more appropriate” ways of engaging in STEM. In other words, the idea that the problem lies with individual students who cannot reach certain achievement outcomes means that deficit thinking tends to defend and promote the status quo.

Thus, in order to make the kinds of substantial, systemic changes that are needed to advance equity in STEM education, deficit perspectives and the related assumptions about learners need to be upended. Research on learning conducted over the last 30–40 years provides powerful new perspectives on learning that offer productive insights that can drive the kind of systemic changes that are needed. These insights include the value of a strengths-based approach, which centers what individuals bring to learning rather than what they lack. This perspective views diversity as a positive element of the community, rather than characterizing it as a deviation from normative standards that must be corrected.

PARADIGM SHIFTS IN CONCEPTIONS OF HUMAN LEARNING

In addition to being shaped by deficit thinking, formal schooling in the United States has also been designed around the assumptions about learning that emphasize transmission of knowledge, decontextualized tasks, and individual achievement (Wrenn & Wrenn, 2009). This is especially obvious in traditional approaches to teaching in the STEM disciplines, which often rely heavily on reading textbooks, listening to lectures, and reproducing factual knowledge on worksheets or tests (discussed further in the following section). However, advances in research on learning reveal human learning as a multidimensional process that involves the complex interweaving of social, biological, emotional, cognitive, ethical, political, and historical dimensions (Esmonde & Booker, 2016; Lee et al., 2020). In this view, questions of identity, culture, race, epistemology, power, and relationality are not ancillary add-ons to human learning. They are constitutive dimensions of learning processes, outcomes, and environments necessary for moving beyond a reductive science of learning and toward holistic views of young people and communities and their ways of knowing (Nasir et al., 2020; Philip, Bang, et al., 2018). This section discusses two approaches to thinking about learning in this more holistic way: first, we look at how sociocultural approaches have and can shape how we understand learning; then, we discuss a learning ecologies approach that affords insight into how learning takes place across settings, and not just in formal learning environments.

These more holistic views of learning draw from research on education, neuroscience, psychology, and anthropology to consider the range of settings and cultural experiences people participate in throughout the life course. They recognize that

- Learning is rooted in evolutionary, biological, and neurological systems.

- Learning is integrated with other developmental processes whereby the whole child (emotion, identity, cognition) must be taken into account.

- Learning is shaped in culturally organized practice across people’s lives.

- Learning is experienced as embodied and coordinated through social interaction (Nasir et al., 2021).

Nasir et al. (2021) suggest that embracing these more nuanced understandings of learning can “disrupt existing patterns of inequality and oppression,” as they offer not only explanations for how learning happens, but also scientific and ethical perspectives on how learning can and should happen within robust and equitable conditions, and toward what ends. The key findings from sociocultural research on learning that we highlight below represent a shift away from earlier understandings of learning and have profound implications for learning in school.

Sociocultural Approaches to Understanding Learning

Sociocultural theories, developed over the last few decades, represent a foundational scientific advancement in understandings of human learning, cognition and development. In this view, all learning is a cultural process that involves historically shaped tools, values, forms of socialization, and goals, and that emerges in heterogenous and evolving ways within and across communities (Cole, 1998; Gutiérrez & Rogoff, 2003; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018; Rogoff, 2003). Understanding the cultural nature of human learning requires engaging with the multiple and evolving communities people belong to and which give shape and meaning to their learning, thinking, doing, being, and becoming (Lee et al., 2020). Here, culture is not only conceptualized as a variable that can be layered onto the study of how people learn; “culture influences what, why, and how people learn, who we consider to be learners, and what we consider to be a good school” (McKinney de Royston et al., 2020).

Sociocultural approaches to understanding learning recognize that learning is a deeply social process of human becoming that takes shape in and through intergenerational relationships, social interactions, and the forms of thinking, relating, and being valued and modeled within and across learning environments. Numerous studies demonstrate that children’s development is highly responsive to social and emotional context, brain development is experience dependent, and the human brain “expects” and is modified by social interactions (Immordino-Yang et al., 2019; Lee et

al., 2020; NASEM, 2018; National Research Council, 2000; Osher et al., 2020). The importance of the quality of social interactions for learning is underscored by the results of a meta-analysis of 99 studies (Roorda et al., 2011) spanning preschool to high school, which found that the affective quality of teacher-student relationships was significantly related to student engagement (average effect sizes of .32 to .39) and achievement (average effect sizes of .16 to .19). These studies also showed that children from low-income families, children of color, and those with learning difficulties were harmed through negative interactions with teachers and benefited more from positive relationships with teachers.

Shifts in the field toward centering the role of social relationships and interactions importantly challenge pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps theories of learning and recognize the power of social relationships as cradles of growth, possibility, and thriving. The zone of proximal development (the space between what a learner can do independently and what they cannot do even with help; Vygotsky, 1978), for example, defines pedagogical assistance and the relationships it is embedded within as allowing learners to experience their emergent capabilities in ways that are developmentally generative. In this view, social and pedagogical relations create the conditions through which learners can experience and grow into their future selves.

Key developments in research on the zone of proximal development highlight the ways that movement in the zone toward greater mastery is always tied to culture, history, power, values, and identity; is bidirectional (educators are also growing through such zones); and is aimed not only at social reproduction but social transformation (Cazden & Beck, 2003; Chaiklin, 2018; Cole, 1996; Gutiérrez et al., 1999; Rogoff & Angelillo, 2002). Supporting learners in the zone of proximal development can involve sustaining ideas and ways of knowing across generations, as well as forms of mediation that cultivate ongoing knowledge making and creativity. Learning is therefore understood as shifts in participation over time (Rogoff, 2003), a process that involves transformation of the individual, their relationship to the environment, and the environment itself (Cole, 1985; Gutiérrez, 2008).

The following example, drawn from Ananda Marin’s work on science learning in the context of family forest walks, illustrates the social nature of human learning and the important role of relationships for supporting learning (see Box 7-2). The example was chosen for the ways it helps illuminate key ideas around culture, social interaction, and moment-to-moment learning interactions.

BOX 7-2

Learning Together: Jason and Jackie

Young children routinely engage in scientific inquiry, including asking questions about the world around them and developing explanations for how things work, as they participate in cultural practices across multiple settings. A child’s sense of identity and repertoire of cultural practices is linked to why and how they engage in learning between persons-in-contexts and places (Marin & Bang, 2018; Nolen et al., 2015; Oyserman & Destin, 2010). The story of Jason and his mother Jackie considers how attention, observation, question asking, and understanding one’s role in relation to others can support learning across time and place.

Jason, Odawa (Indigenous) and Jewish, grew up in the suburban Midwest. During elementary, middle, and high school, he participated in an intergenerational, community-based science program along with his mother, Jackie (Odawa), and younger brother, Sam. The program used place-based and walking pedagogies to facilitate learning about wetland ecologies and to foster the building of relationships with the natural world. Given the fraught history of science among Indigenous and minoritized communities (see Chapter 2 of this report), the program also considered how science can be used to support community wellbeing and sustainable futures grounded in Indigenous ways of knowing and being (Bang et al., 2013; Marin, 2019).

Jason participated in a study on family forest walks that was connected to the program. As a participant in the study, Jason went on five walks with his mother, over a period of 6 months. On occasion, his brother Sam and his father would join them. At the time of the study, Jason was 6 years old and his younger brother was 4 years old. During these forest walks, Jason and Jackie established roles for themselves as “follower” and “leader.” These roles were negotiated and affirmed through talk, movement, and bodily positioning. On one walk, Jason took on the role of leader by walking ahead of his mother. In this position, he set the direction they were walking. Jackie, as the follower, through her movement and talk, honored Jason’s role as the person who was finding their path through forest preserve. At the same time, Jackie also used questions to support Jason in his role. For example, she asked Jason, “So, do you know which direction we’re headed in?” Jason, who was actually uncertain about their direction, responds with both a statement and a question. This organization of talk—question in response to a question—is repeated one more time.

| Jackie: | So, do you know which direction we’re headed in? |

| Jason: | Yes I’m pretty sure. What’s, ok, mom |

| Jackie: | mhm? |

| Jason: | on a compass, |

| Jackie: | mhm |

| Jason: | ok, what’s, what’s going straight when you hold it, what’s going straight that way? (pointing) When you hold it? |

| Jackie: | You mean, south? |

| Jason: | Yeah, what’s going straight this way when you hold the compass? (changes the direction of his point) |

| Jackie: | Uh well, if that’s south, that’s north, going this way is west. |

| Jason: | Ok so we’re going west. |

| Jackie: | And if we were traveling the other way which direction would we be going? |

| Jason: | I don’t, south. |

| Jackie: | (quiet laugh) which way is south? |

| Jason: | That way? (turns his body and points) |

| Jackie: | Ha, no. |

| Jason: | That way. (pointing) |

| Jackie: | Right. |

| Jason: | Oo! This is cold, I get- have to put a hood on, put your hoods on. Can I see? yea |

| Jackie: | It’s kinda hard to tell when it’s cloudy, but if we’re walking this direction late in the afternoon the sun sets in the west, so if we’re headed towards the sun, we would know we were going west. |

| Jason: | Yea, it’s cloudy. |

| Jackie: | Yea. |

| Jason: | It might rain. |

In this exchange, instead of saying that he doesn’t know, Jason uses a series of questions to gather information and maintain an identity as a “knower.” Jason uses questions as both a relevant response to questions and a means to gather information in ways that elicit help in formulating an appropriate response that positions him as knowledgeable—that is, allows him to maintain an identity as a “knower.” His mom asks a clarifying question (“You mean, south?”) that creates an opportunity for Jason to ask another question and gather more information. At the end of this exchange, he is able to provide an answer, “Ok, so we’re going west.” In this exchange, we can see how this use of questions does the work of maintaining Jason’s role as a leader, which was established earlier on in the walk. This small exchange also opens an opportunity for understanding how to use one’s bodily position in relation to land and the sun to determine directions. Furthermore, it creates a context for joint observation and meaning making and illustrates the ways learning about/with the natural world is a cultural process embedded within everyday human activity (Marin, 2019).

Across Jackie and Jason’s walks, Marin found that Jackie routinely made her thinking visible in ways that left space for alternative possibilities and explanations. She also foregrounded multiple ways of knowing, taking on the perspective of more-than-humans and narrating micro-stories to explain observations. When Jason’s younger brother said, “Hello? hello?” in response to a potential animal sighting, for example, Jackie responded “Some people say that, like, animals, they a, they’ll understand, like um, if you speak in Annishnabe, so maybe you should be saying ‘bozhoo.’” Here Jackie marked Indigenous presence (“some people say”) and futurity (“maybe you should be saying”) and mobilized Annishnabe language and ways of knowing as a resource for sensemaking and identity (Marin, 2019). Marin also highlights the role that small disagreements played in expanding explanation and opening new lines of inquiry and shows how whole-body movements were a resource for learning about/with the natural world. Inquiries developed on the walks were sustained and refined through movement across time and place.

SOURCE: The text in this vignette is adapted from Marin (2019) and Marin and Bang (2018).

The vignette in Box 7-2 describing Jason and Jackie’s forest walk illustrates how students are engaged in intellectual practices with their families that are deeply connected to academic learning and that make use of generative interactional practices. Jason’s observations and inquiries were supported by his mother, who engaged in careful forms of joint attention that positioned her son as knowledgeable while providing support to deepen his understandings of and relations with place, land, and direction. Jackie’s statement about the sun and clouds—“It’s kinda hard to tell when it’s cloudy, but if we’re walking this direction late in the afternoon the sun sets in the west, so if we’re headed towards the sun, we would know we were going west”—made her thinking visible within a conversational and embodied flow of walking together as a family. These ways of knowing and reading the land can become resources for Jason’s present and future navigation, and his teaching of others.

While going on forest walks, Jason routinely used questions to direct his mother’s and brother’s attention and position himself as a meaningful contributor to ongoing interactions. He also used questions to establish himself as a knower and person capable of leading others. Across the walks, families used questions and other micro-practices to make entities, phenomena, beliefs, and thought processes visible, to mark and remember places of importance, and to engage in imaginative perspective taking to hypothesize about the lives of and relations with more-than-humans.

As reflected in Marin’s studies of family walks, sociocultural theories of learning and identity highlight the role of such social settings in making multiple ways of knowing and identity resources (material, relational, ideational) available, and in supporting learners to connect their participation in a practice to their sense of who they are in the world (Nasir & Cooks, 2009; Nasir & Hand, 2006). These social and ideational supports are consequential to the forms of interest, disciplinary affiliation, and learning that emerge (or not) within various environments (Erickson & Espinoza, 2021; Gholson & Martin, 2019), particularly as young people move across settings and knowledge systems (Barajas-López & Bang, 2018; Marin & Bang, 2018; Vossoughi & Gutiérrez, 2014). As we take up in Chapter 8 (on teaching), pedagogical models that enact careful attention to students’ ideas, questions, and ways of knowing as tied to expansive views of their cultural lives and worlds, and STEM disciplines themselves, are imperative for equitable learning (Tzou et al., 2021; Warren et al., 2020).

As reflected in the interactions between Jason and Jackie, a growing body of research also shows how schools can learn from the ways positive intergenerational relationships and collaborative activity are prioritized within out-of-school, family, and community settings as both the means and ends of learning (Baldridge et al., 2017; DiGiacomo & Gutiérrez, 2016; Marin, 2020; Nasir et al., 2006; Rogoff, 2003). In such settings, “knowledge and skills are deeply relational with a high positive social

value and thus are bound up in meaningful relationships with the people in the teaching role” (Rogoff et al., 2016, p. 380). Young people are also positioned to understand phenomena in order to contribute to collective endeavors (how to use one’s bodily position in relation to land and the sun to determine directions as tied to finding a path with one’s family through a forest preserve), often coming up with new and improved ways of doing things (Nasir, 2008; Vossoughi et al., 2021).

Such ways of understanding the significance of moment-to-moment social and cultural processes of learning inform asset-based approaches to instruction and call into question some normative approaches to teaching and learning that are informed by deficit perspectives (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995; Mejia et al., 2018; Sparks et al., 2020; Tate, 2001; Valenzuela, 2010; Yosso, 2005). These asset-based approaches, which are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8, esteem what learners bring to the educative process by ensuring that the process and outcomes incorporate and reflect diverse learners’ backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences (Gay, 2010; González et al., 2005; Ladson-Billings, 1994; Paris et al., 2017). When students’ heterogenous cultural practices and ways of knowing are valued, educators and researchers can develop adequately robust and equitable views of learning needs, goals, processes, and outcomes (Gutiérrez & Rogoff, 2003; Medin & Bang, 2014; Nasir et al., 2020; Rosebery et al., 2010).

Learning Across Settings

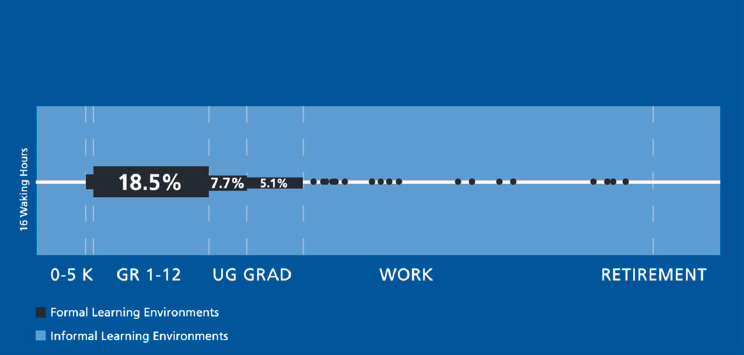

If learning occurs through individual-environmental interactions built upon social relations embodied in diverse cultural contexts, then learning is not something that happens only during school hours and inside classrooms alone. Learning—and particularly STEM learning, which mediates human understandings of how the world works—happens throughout the human lifespan across multiple physical spaces (NASEM, 2014). From a human’s first breath to final exhalation, learning is occurring within family groups, religious communities, community organizations, friend gatherings, digital spaces, the workplace, sports teams, and clubs, in addition to time spent in formal schooling. Indeed, learning is “life-long, life-wide, and life-deep,” with most people in the United States spending only 18.5 percent of their entire life in K–12 schools and the majority of their time learning new concepts, languages, and practices in out-of-school settings (Banks et al., 2007; see Figure 7-1 below).

According to Banks et al. (2007), “life-long learning” involves the learning that extends across a person’s entire lifespan that is often unconscious and naturally “picked up” over time; “life-wide learning” refers to the broad range of experiences that support one’s management of self and others in a lifetime, helping one to adapt to new situations and problem-solve in a variety of contexts; and “life-deep learning” includes the social

SOURCE: Banks et al. (2007). Reprinted with permission from The LIFE Center, University of Washington.

values and belief systems that impact how one acts, alone and with others in the world (pp. 12–13). The diverse physical, social, cultural, and even virtual contexts where learning takes place are sometimes referred to as a “learning ecology.”

A learning ecology framework represents one approach to understanding learning that acknowledges how learners are “simultaneously involved in many settings and that they are active in creating activity contexts for themselves within and across settings” (Barron, 2004, 2006, p. 199). A learning ecologies stance holds that learning can happen anywhere. This perspective helps elucidate how the boundaries between formal and out-of-school learning contexts are often not as clear-cut or impenetrable as they have been made to seem. Learning occurs across school and out-of-school boundaries with engagement deepening as learners notice connections between experiences across contexts, encounter new ideas or interests with family and friends, use technological tools to support further exploration, benefit from the economic and intellectual support of people across both physical and digital communities, and more (e.g., Barron, 2006; Bricker & Bell, 2014; Erete et al., 2021; Kafai et al., 2014; Penuel et al., 2016; Rogoff et al., 2007). The learning ecology framework highlights how learning involves “boundary crossing” and “bi-directionality” across settings (Barron, 2006). Acknowledging the validity of out-of-school learning, and fostering interactions between formal and informal learning settings can make for more equitable preK–12 STEM learning experiences that productively weave together learning across the various and dynamic contexts that learners live in and experience in ways that make STEM learning more inclusive, engaging, and meaningful. In fact, out-of-school STEM experiences can

be powerful contexts for supporting identity development and interest in STEM that can translate to the school setting (King & Pringle, 2019).

Importantly, this broad understanding of learning across settings is not limited to the physical world, but also involves the digital world, where people also engage and interact with one another (Esteban-Guitart et al., 2018). Whether that be in “affinity spaces” where people come together over shared interests and activities (Gee, 2005) or in formally organized online learning contexts necessitated by a global pandemic, learning is characterized by dynamic movement across hybrid spaces as learners develop “repertoires of practice” (Gutiérrez & Rogoff, 2003) across contexts (physical and digital) that reflect personal experiences, interests, and observations of cultural practice.

An ecological perspective on human learning does not hold that out-of-school learning contexts are necessarily richer or more meaningful than what happens during the school day, nor that out-of-school learning should serve as just another tool that supports the learning goals of the school day (Philip & Azevedo, 2017). Yet, when learning is conceptualized as taking shape only in a school classroom, or only when learners reflect back an understanding of how an educator has defined a concept either in or out of school (disconnected from learners’ experiences beyond that context), learners’ opportunities to expand their understandings of STEM and feel empowered to engage with STEM can become stymied. A learning ecologies perspective thus decenters traditional schooling as the singular or most important site for learning, focusing as it does on how learners gain valuable perspectives, experiences, skills, knowledge, and socioemotional development across physical contexts and beyond classroom settings. In practice, however, learners’ experiences outside of the school setting are sometimes not adequately leveraged in STEM classrooms (Bricker & Bell, 2014).

What is known about children’s out-of-school experiences? In particular, what is known about how children from non-dominant backgrounds participate and learn in their communities? Research such as the Funds of Knowledge for Teaching Project (González et al., 2005) illustrates how children from non-dominant groups are resourceful contributors within their families (e.g., language brokers; helping to care for younger siblings; helping with the family economy and domestic upkeep through cleaning yards and doing repairs). Yet, the competencies learners develop outside of school may not be recognized in school settings. For example, Civil and Andrade (2002) describe a 10-year-old who seemed to be having difficulties with school mathematics in the United States yet had had his own set of customers when working at his parents’ bakery in Mexico, where he handled orders and monetary transactions.

Modes of participation in learning and in discourse can also vary across contexts with potential consequences for learning in STEM. Hunter and Civil (2021) illustrate the role of collaboration in mathematical interactions

in two different settings, with Indigenous-heritage students in New Zealand and with families of Mexican origin in the United States. Civil and Hunter (2021) write, “The communities with whom we work value collaboration and focus on the wellbeing and success of the family/community, rather than the more individualistic approach in middle-class communities of European origin” (p. 10).

In their work in Yup’ik communities, Lipka et al. (2005) document the importance of children learning by observing and participating in community activities. The researchers describe Yup’ik teachers’ approach to teaching in the classroom as being based on how they would teach in the community. This work is an example of congruence across school and community. One teacher, Ms. Sharp, “incorporated a form of instruction nested in the traditions of her community and expertly adapted it to the mathematical content of the curriculum […] Ms. Sharp’s use of expert-apprentice modeling and joint activity during math lessons alters social and power relations on multiple levels” (p. 32). The authors comment how in this approach, the children were encouraged to explore and to help each other.

Across geographic contexts, these studies show the importance of collaboration and participation as part of teaching and learning. As Civil (2016) writes, “We need to gain a better understanding of the participation structures, particularly in non-dominant communities” (p. 56). What styles of interaction are encouraged in STEM classrooms? How do they integrate with the community styles of interaction? In their work developing mathematical inquiry environments with Pasifika students in New Zealand, Hunter et al. (2019, 2020) note that the style of argumentation in mathematics classrooms may be difficult for some students if they feel it clashes with their cultural norms (e.g., collaboration vs. individualism/competition; challenging others’ ideas may feel uncomfortable; losing face or their peers losing face). Civil and Hunter (2015) look at features that support argumentation in two contexts (Mexican American students in the United States and Pasifika students in New Zealand). The two contexts point to some common features: importance of relationships; concepts of confianza (trust) and family; supporting students to bring in and continue developing their cultural ways of being and knowing, which include home language(s) and interaction styles. The authors note “the need to gain a better understanding of the potential interactions between everyday out-of-school practices, discipline-based practices, and school practices, and their associated d/Discourses, particularly when working with non-dominant students” (p. 308).

Pedagogical approaches that support connections across settings over time have been shown to support deeper engagement and learning (a more detailed look at pedagogical approaches can be found in Chapter 8). There is also a recognized need for dynamic assessments that can attune to the complexities of students’ movements across contexts and situations, and

expand notions of expertise to account for the innovation and transformation of practices, rather than their mere application (Vossoughi & Gutiérrez, 2014). Rather than a focus on narrow ways of displaying content expertise, one might therefore consider what forms of inquiry, understanding, practice, identity, and relationality take hold for STEM learners over time as they move across contexts and wrestle with the socioecological challenges and demands of our times.

Connecting to Frame 3

Conditions for meaningful learning and critical thinking can be created through cognitively rich and engaging tasks; well-structured supports; caring and supportive relationships; emotionally, culturally, and politically attuned forms of guidance; clarity of purposes and values; and opportunities for authentic sensemaking and multiple ways of knowing (Darling Hammond et al., 2019; Kirshner, 2009; McKinney de Royston et al., 2017; National Research Council, 2000; Rose, 2010; Vossoughi et al., 2021). The insights into learning discussed above afford new models for approaching education. Rather than relying on deficit frames and outdated assumptions about learning, approaches underpinned by this research might adopt Frame 3: Embracing Heterogeneity in STEM classrooms insofar as they are characterized by meaningful efforts to connect the entirety of students’ lives to learning experiences. These approaches might be characterized by efforts to embrace the diversity of ideas that students bring to the classrooms: likewise, cultural differences across students are viewed as assets in the learning process. Further, efforts guided by Frame 3 ask decision makers to capitalize on the ways that students can learn about STEM across a variety of contexts.

The next section looks at how this holistic view of learning can expand understandings of what learning in the STEM disciplines, specifically, can and should do. In this, we consider particularly how STEM learning can be supported through approaches aligned to Frame 3, as well as to Frame 4 (learning and using STEM to promote justice) and Frame 5 (envisioning sustainable futures through STEM).

EXPANDING IDEAS ABOUT LEARNING IN THE STEM DISCIPLINES IN SCHOOL

As noted above, outdated assumptions about STEM learning have tended to constrain what happens in classrooms and limit who is seen as successful in STEM. However, the sociocultural perspectives on learning discussed in the previous section are reshaping approaches to STEM education in productive ways. In this section, we discuss how these more holistic

views of learning prompt and underpin shifts in thinking about the purpose and nature of STEM learning in school in particular.

There has been significant movement over the last 20 years away from a focus on learning decontextualized “content” (as settled knowledge to be memorized) or procedures toward active engagement in disciplinary concepts, practices, and discourse (National Research Council, 2012, 2014). This is underpinned by a strengths-based approach rather than deficit thinking, and an emphasis on the sociocultural dimensions of learning, as discussed above. This view of STEM learning recognizes that the STEM disciplines themselves are cultural constructions and represent highly specific ways of understanding and engaging with the natural and built world that differ markedly from how many if not most people interact with and come to know the world around them. This means that learning in STEM is a process of supporting children and youth to enter into, become proficient with, and expand the practices, discourse patterns, and meaning-making processes of the disciplines.

These developments reflect and support an important shift toward organizing learning in ways that involve young people in the authentic practices of writers, mathematicians, scientists, civic actors, engineers, and artists who apply knowledge to real-world situations, and resituate school learning as part of, rather than removed from, everyday life (NASEM, 2018). These rich, practice-based approaches also support identity development and interest in STEM, while more traditional approaches can undermine productive identity as a STEM learner (Carlone et al., 2014; Kelly et al., 2017; Varelas et al., 2012).

It is important to note that, even within this new approach, entering into STEM is not neutral. The STEM disciplines are heavily influenced by Western European worldviews and have sometimes been used as a tool to devalue, undermine, and even eradicate non-European belief systems (see Chapter 2) and the people who hold them. This shift informs not just the practices around learning, but also understandings of what is being learned, and why, in STEM education. Traditional approaches to STEM education emphasize acquisition of decontextualized knowledge or development of procedural fluency as the main goals of learning. That view often leads to the production of curriculum, teaching, and assessments that conflate learning (and “smartness”) with quickly and correctly arriving at settled right answers rather than engaging in complex inquiry, perspective taking, discussion, and multiple ways of knowing or problem solving. In addition, the notion that knowledge in STEM is neutral—i.e., “free” of cultural context, influence, and history—shapes learning environments that treat sociopolitical and ethical questions as separate from scientific, technological, and mathematical meaning making (McKinney de Royston & Sengupta-Irving, 2019; Philip, Gupta et al., 2018; Vakil & Ayers, 2019), thereby constraining opportunities for ethical reasoning and transdisciplinary imagination

(Takeuchi et al., 2020). Finally, approaches to teaching and educator learning that emphasize compliance and behavior management constrain the deep potential for educators to recognize and build with the complexities of students’ ideas, questions, and emergent forms of STEM meaning making and ethical reasoning (Lee et al., 2021; Rosebery et al., 2010).

These assumptions and the practices that come of them, combined with deficit perspectives, routinely shape students’ disidentification with STEM fields through everyday processes of marginalization and alienation that result from educational policies and forms of decision making across scales (Gholson, 2016; Nasir & Shah, 2011). For example, these perspectives often result in teaching approaches that assume students from non-dominant groups or students who appear to be “unsuccessful” in STEM need to focus on memorization and mastering procedures through direct teaching first, before they can engage in problem solving and meaning making (Jackson et al., 2017; Lubienski, 2007; Sztajn, 2003; Wilhelm et al., 2017).

Evidence of the above can be seen in Sztajn’s (2003) description of two teachers’ beliefs about teaching mathematics in two different socioeconomic contexts. The teacher working in a school where many students were experiencing poverty believed that she had to address what she perceived as her students’ needs and gaps—a perception based largely on her views of their home environment: “These children come from unstable, chaotic homes, which are not good environments for children. Moreover, parents are not willing to participate in the children’s education and they do not provide the appropriate experiences children should have before coming to school” (p. 64). As Sztajn writes, this teacher holds a deficit view of her students’ home lives and sees her role as filling in what she thinks they are lacking. “It is her duty to help students become more organized and responsible” (p. 64). In her teaching of mathematics, this translated into a focus on rules, procedures, and practice of “basic skills,” reflecting a narrow view of mathematics learning. In contrast, the teacher in the school where fewer students were experiencing economic hardship focused on her students enjoying learning mathematics and used problem solving and projects in her teaching. As Sztajn writes about these two teachers, “because their students come from different socioeconomic backgrounds, they are learning different mathematics. Mathematics can represent learning as order or learning as fun. Children are also learning different social behavior patterns through mathematics. Mathematics can mean following rules or thinking critically or creatively” (p. 71).

Approaching STEM learning as discussed above—as a social process wherein individuals and environments interact, where learning takes place across a variety of settings, and eschewing deficit-based thinking—gives rise to new teaching practices and a revised understanding of the purpose of learning that can make education more inclusive and equitable. This opens up new ground around the opportunities STEM learning might afford; in

the sections below, we delve further into three important areas that the approaches discussed above make more accessible: the value of epistemic heterogeneity; the relevance of discussions around the social and ethical dimensions of learning; and transdisciplinary possibilities.

Before we move to explore these themes more fully, we want to note that disciplinary difference within STEM is often an important factor in the understanding of the purpose and practice of learning. That is, while the shift to understanding STEM learning as a social process of engaging in authentic disciplinary practices has informed each of the disciplines in unique ways, it is important to also recognize that the individual disciplines that make up STEM each have their own approaches to meaning making, practice, and discourse. For example, argumentation is a practice employed across science, mathematics, and engineering but the construction of an argument, the nature of evidence, and how arguments can be falsified differ across these disciplines. In mathematics, successful argumentation relies on the use of deduction to “prove” a claim: that is, if the initial claims that one is building their arguments on are true, and if they are using sound reasoning, then the arrived-at conclusion must also be “true.” (Banegas, 2013; Oehrtman & Lawson, 2008). Proof, then, is arrived at by using deductive logic to organize “true” claims into step-by-step, well-reasoned arguments. In science, argumentation is often employed in pursuit of explaining phenomena: in causal contexts in particular, arguments are constructed based on previously held scientific knowledge to help predict what might happen in a test or explain why or how something occurred (or did not occur) under observation (Oehrtman & Lawson, 2008). These kinds of disciplinary differences need to be attended to when developing curriculum and instruction to support diverse learners. In addition, disciplinary differences in epistemology, practices, and discourse can create unique challenges for enacting the kinds of changes that we are calling for in this report.

Epistemic Heterogeneity

A shift toward understanding STEM learning as a social process of engaging in authentic disciplinary practices both in and out of school opens the space for pedagogical and curricular approaches that meaningfully engage with students’ varied cultural and epistemic repertoires (Vossoughi et al., 2021). As Rosebery et al. (2010) ask, what if the field conceptualized “the heterogeneity of human cultural practices as fundamental to learning, not as a problem to be solved but as foundational in conceptualizing learning and in designing learning environments?” (p. 323). This shift supports the idea of diverse processes and pathways as a foundational principle of human learning and requires an expansive view of multiple ways of knowing within STEM disciplines themselves. Here, heterogeneity means moving beyond the singular or narrow forms of language and thought

typically valued in schools—a narrowness that often functions in service of assimilation and flattens the conceptual grounds of STEM (see Chapter 2 for more on assimilation as a goal in U.S. education)—and toward serious engagement with the multiple repertoires of practice, ways of knowing, and points of view students bring—contributions that deepen and expand learning in the disciplines. A growing body of research illustrates the pedagogical and academic effectiveness of disciplinary environments that take up heterogeneity in service of deep learning, and that meaningfully connect curriculum and teaching to students’ families, communities, and cultural life-worlds (Vossoughi et al., 2021). The pedagogical processes, purposes, and outcomes documented within this research challenge curricular designs that treat such heterogeneity as “noise” to be quieted through anchoring experiences that seek “neutral” or singular engagement with disciplinary ideas and practices (Latour, 1988; Tzou et al., 2021), and thereby contribute to the marginalization of minoritized students within disciplinary domains (Calabrese Barton & Tan, 2018; Gholson & Robinson, 2019; Gutiérrez et al., 2009; Madkins et al., 2019; Martin, 2007; Penuel, 2017; Philip, Gupta et al., 2018; Vakil, 2020).

Nasir et al. (2006) provide an instructive example of the ways differences in children’s sensemaking are engaged within an elementary science classroom. This vignette (Box 7-3) was chosen for the ways it helps illuminate what the embrace of multiple ways of knowing in STEM looks like in classroom settings. It also powerfully highlights the consequential role of teachers’ attunement and decision making in how such heterogeneity is taken up (or not) and, thus, how students are positioned as thinkers and learners.

Questions of heterogeneity in STEM disciplines illuminate how opportunities for learning are opened or foreclosed through the ways teachers respond to students’ ideas as tied to the racialized, gendered, and classed bodies and histories with which they (students and educators) move through the world. In the example, Elena’s thinking was in fact valued by the teacher and other students, and propelled elaboration of her ideas as well as new questions. But when such ideas are not valued, one might ponder (a) how students like Serena and Elena are both learning about their positioning in relation to social and intellectual hierarchies, often without the support to question and reshape these political landscapes; and (b) how the ideas offered by students like Elena might be more readily valued when conveyed by students like Serena. Indeed, such differential valuing of ideas depending on the bodies through which they are expressed has been evidenced within the literature (Warren et al., 2020). These are some of the subtle and deeply patterned assumptions through which deficit ideologies constrain STEM knowledge, learning, and learners. Alternatively, this example helps us to consider what can open up intellectually and relationally when multiple ways of knowing are intentionally recognized and engaged.

BOX 7-3

Do Plants Grow Every Day?

Nasir et al. (2006) frame learning as a socially informed process to which children bring different ways of sensemaking. The following is adapted from a description of an exchange wherein they highlight the way a teacher validates multiple ways of knowing:

While discussing the question “Do plants grow every day?,” third-grade children in a two-way Spanish-English bilingual program debated the pattern of growth, and whether you can see it. One girl, Serena, the child of highly educated parents who was considered an excellent student, approached these matters from a stance outside the phenomenon, through the logic of measurement. She argued that growth can be seen through the evidence of measurement on a chart of a plant’s daily growth. Another girl, Elena, approached the question differently. The child of immigrant, working class parents, Elena was repeating third grade. She took up the question of how one can see a plant’s growth by imagining her own growth through “the crinkly feeling” she has when her feet are starting to outgrow her socks. In this event, Elena’s way of thinking was valued by the teacher, who repeated (with appreciation) a key part of Elena’s insight (“So, plants can feel themselves grow?”), joining with Elena and making space for her and other students who shared related experiences and posed new questions (adapted from Nasir et al., 2022).

Following this vignette, Nasir et al. discuss the ways Serena’s approach conforms with normatively held conceptions of scientific reasoning, while Elena’s approach may be undervalued or even dismissed in current schooling configurations, with profound implications for her learning and sense of herself as a thinker. Serena’s reasoning strategies represent one important tool among a wide range of sensemaking repertoires in science. As the teacher in this instance recognized, Elena’s efforts to imagine her growth through visual and narrative resources also reflect key scientific practices, including how scientists place themselves inside physical events and processes in order to gain a deeper understanding of phenomena and their behaviors (Keller, 1983; Ochs et al., 1996; Wolpert & Richards, 1997). Thus, the routine privileging of the ways of displaying understanding offered by Serena represent not only reductive views of children and their sensemaking, but reductive (and stereotypical) views of science that are out of sync with the “fundamental heterogeneity of science-in-action as an intricate intertwining of conceptual, imaginative, material, discursive, symbolic, emotional, and experiential resources (Biagioli, 1999; Galison, 1997)” (Nasir et al., 2006, p. 494).

SOURCE: The text in this vignette is adapted from Nasir et al. (2020).

The example of Serena and Elena raises critical questions around casting epistemic singularity (or one way of knowing) as more “rigorous,” given the intellectual complexity and generativity that has been evidenced in settings that engage multiple perspectives, values, and knowledge systems as central to the work of disciplines (Warren et al., 2020). Key here are the ways the expansive visions of STEM education outlined throughout this report require historicized forms of STEM learning whereby learners are supported to attune to the layered intellectual histories and possible futures of STEM fields, and to the ways political and ethical concerns deeply shape STEM concepts, methods, practices, and inquiries (Martin et al., 2010; Medin & Bang, 2014; Philip & Azevedo, 2017).

These developments have several implications for how disciplinary knowledges and practices are conceptualized and studied within research on learning. The “crinkly” feeling Elena described when she outgrew her socks was not only a powerful way to consider how one can see plants grow, but also a way to connect scientific ideas and phenomena to her everyday experience as a growing, living being.

When expansive learning is achieved, “teachers and students together narrate deep connections between phenomena and their experience, raise and explore unexpected questions, and engage routinely with unspoken aspects of phenomena (e.g., Is water alive?)” (Bang et al., 2017, p. 36). Importantly, such practices rely on teachers’ skill in attuning to students’ ideas as connected to science rather than off-topic or disruptive (Calabrese-Barton & Tan, 2010). As the story of Selena and Elena reflects, this attunement also requires a wider view of the ways multiple repertoires and ways of knowing shape the work and edges of STEM disciplines. The pedagogical attunements and understandings of disciplines that accompany the shift toward STEM practices are therefore essential to disrupting the persistent marginalization of African American, Latinx, and Native American students in science (Bang et al., 2017).

The shift to seeing STEM learning as engaging children and youth in disciplinary practices and discourse as well as leveraging the knowledge and experience they bring from their lives outside of school connects to Frame 3 (embracing heterogeneity). Combined with an asset-based perspective, these insights about STEM learning push toward practices that see diversity of life experiences and novel ways of understanding the world as resources for more robust classroom discussion and deeper learning experiences.

Exploring the Social and Ethical Dimensions of STEM Disciplines

Scholars are increasingly recognizing disciplinary domains as evolving and internally heterogenous, replete with debates, tensions, and complexities that are often flattened within settled forms of school-based disciplinary

learning (Warren et al., 2020). Settings that recognize disciplines as always changing (Latour, 1988) position students as agentive thinkers who can critically interpret and participate in evolving domains, and productively wrestle with the social and ethical assumptions and consequences of all knowledge production (Harding, 1993; Jaber & Hammer, 2016; Martin et al., 2010; McKinney de Royston & Sengupta-Irving, 2019; Philip, Bang et al., 2018; Vakil & Ayers, 2019). The work of Morales-Doyle et al. (2019), for example, draws on a high school chemistry curriculum they designed around the “social-scientific issue” of heavy metal contamination to analyze how teachers both utilized and expanded Next Generation Science Standards (2013) to strengthen their applicability to community issues. While the standards support students to examine the benefits of science, for chemistry they tend not to address the harms—and the ways “both harms and benefits are unevenly distributed” (Morales-Doyle et al., 2019). Examining such questions from the perspectives of students, Vakil (2020) found that students of color in a computer science course engaged in astute forms of disciplinary values interpretation, critically reading the values of the domain in relation to who they are and might become within it.

The ability of students to engage productively in exploring the ethical and social implications of STEM disciplines is underscored in a study of learning and teaching socially responsible computing (Ryoo et al., 2021). This study focused on teaching and learning in one classroom of students taking an AP computer science course that was intentionally designed to connect computer science to students’ lives and to open up space for them to consider ethical and social implications of the technology. The students in the class, all Latinx and 40 percent female, engaged in rich discussions about the power that tech creators hold, the non-neutral aspects of technology and how it connects to their own social worlds, and the ethical and social implications of computing-based decisions. These discussions were catalyzed and supported through the teacher’s explicit instructional moves.

Our third vignette (Box 7-4) probes further into the ways environments that are designed STEM learning as political and ethical can recognize children’s full humanity as thinkers and historical actors, and nurture their imagination and wellbeing. Davis and Schaeffer (2019) problematize the tendency to teach about water in K–5 in ways that divorce the properties and utility of water from its deeply politicized history; water is a resource that has been limited, compromised, and intentionally withheld from nondominant communities. In their collaborative curricular project, they were specifically focused on understanding the sensemaking and experience of Black children.

BOX 7-4

Water Is Life

Davis and Schaeffer approached disciplinary learning about water within a recognition that children already had understandings of the politics of water. Students knew that water is sometimes denied to people due to racism and were aware of the stigmas associated with people whose water was cut off. The children also held sometimes contradictory views of water as a right and as a commodity. The text below is an adaptation of a passage in which Davis and Schaeffer underscore the multiple levels at which learning about water took place:

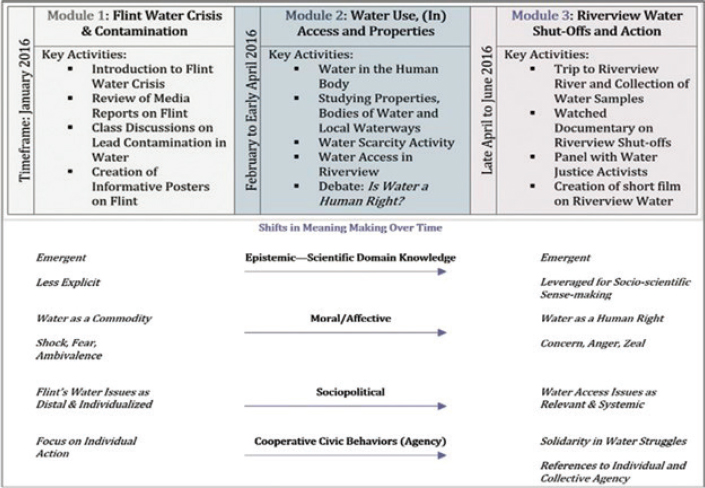

Early in the unit, children saw clean water access in Flint as a distal, individualized problem. Students expressed emotional fear and outrage. Nonetheless, they seemed to accept the status quo of water as a commodity. Later, with the introduction of the Riverview case and additional activities, there were several important shifts. First, children began to understand water justice as a sociopolitical (and in some cases raced) and ethical issue. Their articulations demonstrate understandings of the Flint and Riverview cases as interrelated examples of a larger systemic problem. Children leveraged scientific domain knowledge gained over the course of the unit to situate water as a human right.

The table below summarizes key activities in Davis and Schaeffer’s unit and shifts in students’ meaning making over the course of the lessons:

Davis and Schaeffer’s work on the “Water is Life” unit has critical implications for engaging socioscientific issues in science classrooms. They question whether justice-oriented science pedagogy places an undue burden of responsibility on Black children to contend with issues that they didn’t create. Without necessary opportunities for exploration and play, they express worry about if and how critical science education might function in ways that unintentionally compromise children’s socioemotional wellbeing. Davis and Schaeffer therefore caution against conceptions of justice-oriented science education that focus exclusively on the identification of problems. They make the case that curricula in elementary science classrooms must also feature examples of liberation, imagination, and healing.

At the same time, Davis and Schaeffer do not see children’s expressions of fear and anger as a legitimate rationale for limiting justice-oriented science pedagogy in elementary classrooms. Children in Riverview and Flint, they argue, have a right to feel angry. Davis and Schaeffer encourage increased attentiveness to how science learning environments are designed in support of just futures. They ask, “What types of socio-emotional and disciplinary supports do children require when grappling with problems close to (or far away from) home? How might experiential knowledge serve as both a resource and an area of vulnerability in science classrooms?” These questions, they urge, should speak to the ethical imperatives of teachers and researchers.

SOURCE: The text in this vignette is adapted from Davis and Schaeffer (2019).

Visions of STEM education that meaningfully engage with the cultural, historical, ethical, and political dimensions of knowing and learning also recognize that complex problems require not only multiple disciplinary perspectives and tools (interdisciplinary learning), but new forms of thinking and problem solving that emerge across disciplinary boundaries (transdisciplinary learning), where “learning in one discipline can be deepened through engaging with other disciplinary lenses” (Takeuchi et al., 2020). Based on a commitment to “questions greater than the discipline itself,” Takeuchi et al. assert that new interactions across disciplinary boundaries can “lead to the emergence of new concepts, representations, and applications, that ideally should also re-centre voices from the margins” (2020, p. 6). These researchers exemplify the complex thinking this approach makes possible through recent work on critical numeracy (Das & Adams, 2019), critical ecological sustainability (Bang & Marin, 2015; Kim et al., 2019; Lam-Herrera et al., 2019), and macroethics (Gupta et al., 2019; Philip, Gupta et al., 2018). As exemplified through the aforementioned “social-scientific issue” of heavy metal contamination and careful attention to the harms and benefits of chemistry (Morales-Doyle et al., 2019), such work brings new relevant

phenomena and ideas into view and deepens multiperspectival engagement with existing concepts and practices (Tucker-Raymond & Gravel, 2019).

Recent efforts to examine the political and ethical dimensions of STEM learning underscore this generative complexity. McKinney de Royston and Sengupta-Irving (2019) consider how teachers can support students to not only enact STEM learning for social change, but to recognize the ways “making STEM answerable to the unmet needs and desires of minoritized people” (p. 279) can help develop new concepts and ways of knowing. Similarly, Vakil and Ayers (2019, p. 456) argue that centering students’ identities “is too often a matter of using culturally relevant moments as a ‘hook’ to interest students without deeply reframing the underlying values, practices and purposes of STEM disciplines.” Engaging students with the political and ethical in STEM offers entry points into civic action and civic agency and can help students become more aware of their own agency within their communities (see the special issue of the Journal of Research on Science Teaching on Community Driven Science, October 2023 [Ballard et al., 2023]).

These approaches also recognize that many students and families have encountered histories and ongoing structures of scientific harm firsthand and bring important critiques, visions, ways of knowing, and forms of transdisciplinary meaning making to the practice of STEM. Davis and Schaeffer’s work on “Water is Life” reminds us that meaningfully contending with such harms in the context of critical STEM education should involve the careful design of curricular and pedagogical supports that nurture students’ wellbeing, healing, and imagination.

Connecting to the Frames, Continued

As we discussed above, approaches to STEM learning that encourage children to leverage their own knowledge and experiences as they actively participate in STEM disciplinary practices and discourse connect directly to Frame 3 (embracing heterogeneity). But as approaches to learning in the STEM disciplines continue to evolve, so too do opportunities for supporting equity: for example, the more learning in STEM is understood as a social process wherein individuals and environments interact, where learning takes place across a variety of settings, and where asset-based approaches are standard practice, the more decision makers can support learning opportunities oriented toward supporting justice and sustainable futures. Ultimately, the committee contends that engaging with social, ethical, and political issues in STEM can support decision makers in pursuit of outcomes aligned to Frames 4 and 5 (learning and using STEM to promote justice, and envisioning sustainable futures through STEM). In giving students space to develop a sense of their own agency in STEM learning experiences, decision makers can support students in developing

an understanding of how STEM can be leveraged to help them realize that agency in positive ways.

TRANSFORMING LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES IN STEM

Transformative visions for equity and justice in STEM education require deep attention to the underlying theories of learning that guide the design of learning environments, teaching and learning processes, valued forms of knowledge production, assessment, teacher education, family and community engagement, and broader approaches to change making at both macro and micro scales of activity. Sociocultural approaches help to disrupt a view of dominant cultural practices (e.g., ways of doing science; approaches to teaching and learning; conceptions of nature-culture relations; valued forms of classroom discourse and attention) as unexamined norms against which all students are measured (Artiles, 1998; Erickson, 1984; National Research Council, 2009; Vossoughi et al., 2021). They also assert the need to examine how the naturalization of unequal outcomes across race, class, and gender is used to locate artificial deficiencies in students and obscure the ongoing production of stratification, what Sengupta-Irving (2021) describes as the creation of “‘smart’ or ‘dumb,’ ‘success’ or ‘failure,’ ‘desirable’ or ‘undesirable’” (p. 188).

Nasir et al. (2021) elaborate the lived consequences of these political structures and processes for human development: “Processes of racism and other forms of oppression are antithetical to meeting the developmental needs of learners, because oppressive processes are premised on the notion of denying full humanity, and ensuring that only some have their full human and developmental needs honored” (p. 562). Importantly, research has shown how these oppressive practices, as well as justice-oriented practices that support wellbeing, take shape in moment-to-moment interactions within learning environments through the patterns of talk, interaction, movement, attunement, positioning, and sanctioned knowledge routinely enacted in schools and other educational settings (Espinoza et al., 2020; Philip, Gupta et al., 2018; etc). Nasir et al. (2006) write:

As youth make their rounds through the varied settings of their everyday lives—from home to school, mathematics class to English literature class, basketball team to workplace or church youth group—they encounter, engage, and negotiate various situated repertoires of practices […] Navigation among these repertoires can be problematic at any time in any place for any human being. However, for youth from non-dominant groups (i.e., students of color, students who speak national or language varieties other than standard English, and students from low-income communities), this navigation is exacerbated by asymmetrical relationships of power that inevitably come into play around matters of race, ethnicity, class, gender, and language. (p. 489)

A large body of research has demonstrated that the possible disruption and transformation these longstanding inequities and forms of supremacy depends on curriculum and teaching that are deeply connected to students’ lives, identities, and cultural ways of knowing (Bang et al., 2014; Cazden et al., 1996; González et al., 2005; Gutiérrez et al., 1999, Ladson-Billings, 1995; Lee, 2001; Martínez, 2017; Martínez & Mejia, 2020; Moje, 2004; Muhammad & Love, 2020; Nasir, 2002; Paris & Alim, 2014; Rosebery et al., 2010; Vossoughi, 2014; Warren et al., 2020), as well as learning environments that center psychological safety, belonging, dignity, and care (Antrop-González & De Jesús, 2006; Baldridge et al., 2017; Espinoza et al., 2020; Gholson & Robinson, 2019; McKinney de Royston et al., 2021).

Taking a more holistic approach, leading edges of the field are attuning to the consequential ways that relationality, identity, emotion, ethics, and cognition interweave in moment-to-moment learning interactions. Zavala (2018) conceptualizes generative learning experiences as processes of “rehumanization that take place in and through cognitive work” (p. 109), what Rose (2014) has described as a substantive sense of “intellectual respect” conveyed through educational talk and interaction. Similarly, Espinoza et al. (2020) offer the notion of educational dignity, defined as the “multifaceted sense of a person’s value generated via substantive learning experiences that recognize and cultivate one’s mind, humanity and potential” (p. 325). Just as the careful attention to history within sociocultural theory can be used to contextualize and analyze unjust educational arrangements, it can also illuminate the forms of community resistance and resurgence that have consistently provided spaces of care, educational creativity, and thriving despite efforts to impede self-determination (Bang et al., 2014; Espinoza, 2009; Gholson & Robinson, 2019; Givens, 2021; Gutiérrez, 2009; Marin, 2020; McKinney de Royston et al., 2017; Siddle-Walker, 2000).

Our attention to the details of pedagogical discourse and student sensemaking throughout this chapter underscores the profound role of language and social interaction in the construction of learning and educational opportunity. Supporting students to read all scientific and mathematical language and representation as culturally and historically situated can cultivate more dynamic relationships with STEM learning, particularly for students whose ways of knowing have been routinely excluded from school-based science. Connecting expansive views of disciplinary domains with robust conceptions of human learning, Nasir et al. (2021) write, “Teaching in antiracist and justice-oriented ways requires a commitment to move beyond colonial terms for learning, embracing multiplicity, and seeing learning as intimately connected to processes of liberation and freedom” (p. 560). This is what it can look like to broaden participation beyond access.

CONCLUSIONS

This chapter has outlined recent paradigm shifts in understandings of human learning, and in STEM learning in particular. Within this discussion, we consider how these contemporary understandings of learning suggest ways of reorganizing learning experiences, instruction, and other structures of schools to maximize the potential of learners and open up STEM in ways that promote more equitable learning. Throughout this chapter we have connected these insights to the five frames for equity, in particular pointing to the ways that emerging ideas about learning are opening up new possibilities for decision makers directly supporting student learning experiences.

But in using the frames for decision making, the committee notes that decisions for equity are occurring at all levels of the system, not just in the classroom. Awareness of these newer insights on learning requires that all actors in the system are reflecting on their assumptions about learning and about STEM, because those assumptions necessarily inform decisions and actions. Asset-based perspectives that embrace cultural diversity and recognize STEM disciplines as evolving are more productive for advancing equity than deficit perspectives; actors, then, can support more productive action for advancing equity when they too have evolved their own anchoring assumptions about learning and learners.

Further, in order to truly enable decision makers in schools and classrooms to do this work effectively, actors at other levels of the system will want to consider what kinds of moves can be made within their respective domains to better position educators and school-level administrators to be able to leverage newer understandings of learning. What are the structural supports necessary at the federal, state, district, and school levels in order to support student learning in STEM? For example, if embracing heterogeneity is the desired outcome for student learning, what kinds of professional learning experiences do educators need to have in order to support student learning in this capacity? The answers to questions like these have implications for professional development providers, school and district administrators, and state actors responsible for allocating resources of all kinds, among others. We continue in this exploration in the following chapter, where we discuss what is known about supporting equitable instruction in the STEM disciplines. We conclude the chapter by offering the following major findings:

Conclusion 7-1: Learning is a cultural, social, political, and historical process that takes place across the settings/ecosystems of learners’ lives, including families, lands/waters, community settings, and schools. These varied learning experiences are equally important for shaping how people know and understand the world but are not always acknowledged or leveraged in formal STEM learning contexts.

Conclusion 7-2: Inequities can be reproduced and/or disrupted and transformed through teaching and learning interactions and through the ways that learners’ sensemaking is recognized and cultivated.