Equity in K-12 STEM Education: Framing Decisions for the Future (2025)

Chapter: 10 Instructional Materials, Time, and Resources

10

Instructional Materials, Time, and Resources

In Chapters 7, 8, and 9, we describe new insights into learners and learning, and various strategies for supporting teachers and connecting them with necessary resources as they work toward equity in their classrooms. Although strong teaching is a critical component of achieving equity in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education, this on its own is not enough to overcome the considerable inequities in the U.S. education system. Indeed, implementing the more expansive forms of teaching and learning in STEM that we described earlier in this report requires the support of a range of material and social resources. In the current education system, these resources are unevenly distributed, contributing to the inequitable outcomes described in Chapter 4. Additionally, as we discuss in this chapter, the materials themselves can perpetuate inequities: when supportive instructional materials and resources are developed based on harmful conceptions of learners or on narrow conceptions of the STEM disciplines, educators are tasked with working overtime to overcome inequities that are “baked in” to the materials in their classrooms. In this chapter, we discuss the role of instructional materials, time, and other resources in supporting equity in STEM education.

INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS AND EQUITY IN STEM EDUCATION

Instructional materials are the intellectual and material resources that teachers use to teach in their classrooms and are a crucial component in efforts to advance equity in STEM education. In this section, we will discuss

the important role of instructional materials in STEM education, as well as the various inequities in how materials are currently distributed and used in classrooms around the country. We then turn to a discussion of how instructional materials can be leveraged to advance equity and justice, and the role that different decision makers play in supporting the development, distribution, and use of instructional materials that advance various equity aims.

In order to understand the role of instructional materials in STEM education, it is first critical to understand the breadth of what instructional materials are. Often, terms like instructional materials, instructional resources, and curriculum materials are used interchangeably, but the subtle differences across terms are important for considering how different actors might approach equity. For the purposes of this report, we consider a curriculum to be an organized plan of instruction comprised of a sequence of instructional units that engage learners with specific content or ideas. Curriculum materials, then, are the tool and resources that are intentionally designed to specifically support curriculum in achieving desired learning aims. Instructional materials encompass curriculum materials, but may also include a broader set of tools that can be used across different curricula or content. Both curriculum and instructional materials may include textbooks, web-based resources, learning activity supports, formative assessment supports, and other forms of guidance and resources.

Instructional materials are a critical component of how teachers teach in all subjects, but their value is particularly important in the STEM disciplines, and even more important when teachers are working toward the more expansive forms of teaching and learning described in Chapters 6, 7, and 8. The more teachers are working toward robust conceptions of the STEM disciplines, the more support teachers need in bringing concepts to life.

High-Quality Instructional Materials and Equity

Despite their considerable importance for supporting learning in STEM, high-quality instructional materials are not equitably distributed across the system. According to the most recent national survey of K–12 science and mathematics teachers, the National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education (NSSME+), the most frequently used types of instructional materials in science classrooms are commercially published textbooks and supplementary materials, followed by commercially published kits/modules. This is particularly pronounced in middle and high school, where the percentage of classes using commercially available textbooks ranges from 87 percent in middle to 95 percent in high school (Banilower et al., 2018). Across the nation, over two-thirds of science classrooms are using textbooks that are over 6 years old, with 73 percent of higher-poverty schools using older textbooks versus 67 percent of the lowest-poverty schools. Results of

the survey also reveal that the majority of science teachers across the country are cobbling together instructional materials from multiple sources, with only 26 percent of educators saying they use a single textbook throughout the year (Banilower et al., 2018). So, while many teachers do design their own materials and use other online sources to support their work, it is clear that commercially available textbooks and modules dominate the learning landscape in science classrooms across the country.

Recognition of these inequities and of the potential power of instructional materials to improve student learning in a cost-effective way has led to a recent emphasis on high-quality instructional materials as a lever for improving education. In 2017, the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and a cohort of interested states launched the High-Quality Instructional Materials and Professional Development (IMPD) Network dedicated to ensuring that every student, every day, is engaged in meaningful, affirming, grade-level instruction. Currently, the network supports 13 states in supporting districts to select high-quality curricula and curriculum-connected professional development. The initial focus of the network was on English language arts and mathematics, but it has recently expanded to include science and social studies. Efforts of this network are encouraging and seem to have increased the number of students in participating states who have access to high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) (Council of Chief State School Officers, 2023). More broadly, data from the American Instructional Resources Survey indicates that use of standards-aligned mathematics curricula is increasing across the country (Kauffman et al., 2021).

While there is strong evidence for the potential of curricula to improve student learning, research on the specific characteristics of effective curricula in each of the disciplines in STEM is still emergent (Steiner, 2017). However, in education practice, there is agreement that the characteristics of HQIM are aligned to standards, provide rigorous instruction, are research based or research informed, reflect diversity and inclusion, and have connected professional development. This emphasis on HQIM with these characteristics is now informing state and district selection and adoption of curriculum materials (see the section below for more detail on how states select and adopt materials).

While diversity and inclusion are often included as a characteristic of HQIM, in many discussions of HQIM in STEM attention to equity is limited. It may be evident through a focus on student agency, supporting opportunities for students to make connections to their homes and communities, openness to linguistic and cultural diversity, and ensuring that a variety of racial or ethnic groups are represented in the materials (NextGen Science et al., 2021). These approaches, while valuable, mainly emphasize Frame 3 (embrace heterogeneity), with less attention to Frames 4 (using STEM to promote justice) and 5 (envisioning sustainable futures).

Limited and sometimes implicit attention to equity as part of HQIM can be problematic because STEM instructional materials have emerged from the same inequitable education system, as described in Chapters 2 and 3 of this report. Although this tide is turning, STEM curricula are often narrowly focused on Western ways of knowing, being, and doing while simultaneously marginalizing ways of knowing from Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other people of color (Bang et al., 2012; Rosebery & Warren, 2008). This is particularly troublesome in light of what is now known (and discussed in Chapter 7 of this report) about how to support meaningful learning in STEM and the importance of leveraging students’ cultural identities. When instructional materials reify traditional ideas about the STEM disciplines themselves and about who is capable of contributing to the disciplines, it stands to reason that those materials will be less supportive for teachers looking to leverage students’ full identities in learning environments. This remains true for instructional materials that were expressly designed with more expansive ideas about learning in mind: unless materials explicitly embrace heterogeneous ways of knowing in STEM, they are likely to support teachers’ inadvertent reproduction of dominant paradigms. As Chapter 6 of this report outlines, depending on which equity frame(s) are brought to the design of instructional materials, instructional materials may leave unexamined the ways of knowing, being, and doing that are accepted in STEM classrooms. For example, science curricular materials may ground investigations into phenomena in students’ questions, yet only allow narrow kinds of questions in the sensemaking space or not account for the heterogeneity of families’ and communities’ everyday practices.

Teachers’ Use and Adaptation of Curriculum Materials

Even with high-quality instructional materials in place, how teachers take up and engage with instructional materials varies based on a number of factors (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022). Teachers come to instructional materials with pre-existing dispositions, sets of knowledges and practices, and assumptions about students, families, the disciplines, and learning—and they interpret and adapt materials through those lenses. Instructional materials are therefore one of many factors that influence the STEM education experience of learners. The Brilliance of Children report (NASEM, 2022) summarizes the factors that can influence teachers’ adaptations of instructional materials in science, drawing from the research literature (see Table 10-1).

As the table outlines, one of the factors shaping teachers’ adaptations of instructional materials is their beliefs—about learners’ abilities, assessment, and classroom management. For example, if a teacher holds deficit beliefs about students’ abilities to engage in rich sensemaking about the

TABLE 10-1 Factors Shaping Teachers’ Adaptations of Curriculum Materials

| Factors | Examples of Results |

|---|---|

| Teachers’ Knowledge and Beliefs | |

| Teachers’ understanding of the science practices | Stronger understanding of certain practices may lead teachers to include those practices. |

| Teachers’ beliefs (e.g., about learners’ capabilities, assessment, classroom management) | A belief that children cannot engage in sophisticated sensemaking may lead teachers to omit opportunities for sensemaking. |

| Perceptions of time constraints | Limited time may lead teachers to omit lesson segments. |

| Characteristics of the Curriculum Materials | |

| Comprehensive or kit-based materials | May support teachers in teaching accurate science content; no clear effect on children’s learning. |

| Inquiry or practice orientation | Greater orientation toward science practice may lead to engaging children with the practices. |

| Specific educative features yield different effects | More situated educative features and features that support principled adaptation and engagement in sensemaking seem helpful. |

| Contexts of Curriculum Material Use | |

| Classroom contexts (e.g., mentors) as supportive or not supportive of adaptation | Having mentor teachers who model the importance of principled adaptation of curriculum materials seems helpful. |

SOURCE: NASEM (2022).

natural world, they may omit or adapt opportunities for sensemaking in the curriculum (NASEM, 2022). These kinds of influences are one of the reasons that it is essential to couple adoption of high-quality instructional materials with professional development. In order to advance equity, such professional development opportunities will need to explicitly engage with equity-related issues as reflected in the discussion of teachers’ professional learning in Chapter 9.

Instructional materials themselves can also be educative when they incorporate multiple strategies for supporting teachers as they take up new kinds of teaching strategies and practices as part of their use. This means that instructional materials that explicitly attend to equity may be important tools for shifting instruction to reflect the models discussed in Chapter 8.

Educative curriculum materials are materials that have at least five characteristics: (a) they help teachers learn how to anticipate and interpret learners’ sensemaking, (b) they support teachers’ learning of subject matter, (c) they help teachers connect to other curriculum units across the year, (d) they lend transparency to design decisions made by developers, and (e) they promote teachers’ pedagogical design capacity, or adapting curriculum to meet the needs of their learners (Davis & Krajcik, 2005). When these characteristics are in place, teachers are better able to make sense of how to use instructional materials in their own contexts.

Further, research has shown that teachers tend to take up and use supports that are situated within the lessons themselves—such as narratives of teachers using a particular part of a lesson, rubrics, and examples of students’ sensemaking (Arias et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2016, 2017; NASEM, 2022). The context of use—what supports are available, both within the written materials and in terms of mentors or others in the setting to support teachers in implementation—is another important factor, especially given the durability of teachers’ beliefs about their disciplines, their students, and their families. Put more specifically, teachers will more likely take up or adapt aspects of instructional materials that are in line with their beliefs or current states of knowledge. Intentionally placed supports within lessons can nudge teachers’ sensemaking around their own practice, content, and pedagogical decisions (Davis & Krajcik, 2005).

Selecting Instructional Materials

Prior to making their way into schools and classrooms, instructional materials need to be selected for use. The process of that selection varies by states and localities, with some states mandating instructional and curricular materials, and others leaving that selection up to districts and/or schools (see Box 10-1). As noted earlier, the vast majority of teachers also supplement mandated instructional materials with additional resources. In this section, we discuss the processes and tools that support the selection of instructional materials, as well as who is involved in that work.

Beyond state mandates, ratings from national entities and state leaders are powerful guides for local adoption of what are considered high-quality curriculum materials and are therefore deeply consequential for the kinds of curricula that get adopted (NASEM, 2018). In establishing these ratings, state and local education agencies often rely on rubrics developed by researchers or other organizations designed to isolate different quality criteria and help decision makers evaluate instructional materials in relationship to one another. However, if these rubrics do not expressly attend to issues of

BOX 10-1

How Instructional Materials Are Adopted Across All 50 States

A majority of states have no specific policy addressing instructional materials. Of the 21 states that do have formal processes for the approval, adoption, or procurement of instructional materials, 17 exercise formal control, and the remaining 4 delegate decision making to districts with no state oversight. Of the 17 states with formal authority over curricular decisions, the level of control varies significantly.

Six states maintain a high level of control over curricular decisions in two ways:

- They mandate that districts choose specific materials and provide very limited exemption/waiver policies.

- They restrict spending allotments, meaning that they require a specified percentage of state funds be allocated for state-approved options only.

Of these six, Nevada, South Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia maintain approval rights for all instructional materials used in the state and require districts to secure a waiver or submit non-approved texts for state review. Oklahoma and New Mexico require that 80 percent and 50 percent, respectively, of state funds be used on state-approved instructional materials.

Seven states offer more flexibility for districts to select instructional materials. California, Florida, Virginia, Alabama, and Utah also allow districts to make curricular choices, as long as their adoption processes meet certain state-defined criteria for stakeholder engagement or curricular quality. Louisiana, without any state mandates, has developed a tiered-review system and incentivizes districts to use the highest-rated materials. In 2018, Nevada followed suit and adopted a policy to categorize instructional materials according to quality.

Often, states with low control over district curricular choices neither restrict district choice nor provide incentives to select the best materials. North Carolina and Texas, for example, offer only loose guidance that districts can choose to heed or ignore, with no statutory consequences. Mississippi, on the other hand, has begun to take a more active role in ensuring the use of high-quality instructional materials, despite the state having limited authority over local curriculum decisions. Last year, Mississippi developed a series of high-quality instructional materials “review rubrics” to assess curricula, and has realized the value of state-level incentives, such as procurement policies, in encouraging districts to choose wisely when adopting curricula.

SOURCE: Text Adapted from Choosing Wisely: How States Can Help Districts Adopt High-Quality Instructional Materials (https://www.chiefsforchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/CFC-ChoosingWisely-FINAL-1.pdf)

equity and justice, or treat them inadequately, then those dimensions are not considerations for what counts as “high-quality” curricula.

Since 2015, EdReports, an independent non-profit organization, has carried out and published free reviews of K–12 instructional materials, using an educator-led approach that measures standards alignment, usability, and other quality criteria. The stated goal of these reviews is to increase the capacity of teachers, administrators, and leaders to seek, identify, and demand the highest-quality instructional materials. High ratings by EdReports have become a hallmark of quality and often drive selection and adoption of materials by states and districts. Given the widespread influence of EdReport reviews, it is important to understand whether and how equity-related criteria are part of the review process.

EdReports makes its review process and criteria publicly available on its website. The review process involves a sequential review through three gateways. The first two gateways include criteria that address whether instructional materials are aligned to standards. The third gateway focuses on “usability” and criteria for this gateway assess whether materials facilitate student learning and enhance a teacher’s ability to differentiate and build knowledge within the classroom. Materials must meet criteria for the two gateways before they are even reviewed for usability.

The set of criteria that are most relevant to the dimensions of equity we have been discussing in this report appear under Gateway 3 under the subsection “student supports” (see Box 10-2). These criteria connect most closely to Frames 2 (opportunity and access) and 3 (embracing heterogeneity). To support heterogeneity, these criteria focus mainly on leveraging the knowledge from family and community that students bring to the classroom and including representations of diverse people engaged in STEM. They do not represent the part of Frame 3 that emphasizes broadening conceptions of traditional disciplinary concepts to include different ways of knowing. Ideas about justice and sustainability as represented in Frames 4 (using STEM to promote justice) and 5 (envisioning sustainable futures) are absent.

While the EdReports review tools and criteria cover some elements related to equity, they do not explicitly call them out, nor do they cover all of the elements the committee has described. This means that the ratings provided by EdReports that many states and districts use to identify HQIM do not reflect a robust conception of equity. However, there are additional tools that focus explicitly on equity-related criteria developed by other organizations and states that are available for use. In 2022, EdReports released the results of a landscape study that analyzed 15 resources in use across the country that can be used for evaluating materials for culturally responsive practices of the sort described in Chapter 8 of this report (EdReports, 2022). The goals of the analysis were to help educators and education

BOX 10-2

EdReports Review Criteria with Connections to Equity

The following criteria, all found under Gateway 3: Usability, in the subsection on student supports, have conceptual connections to dimensions of equity discussed in this report. These same criteria appear in the review tools for both mathematics and science at all grade levels (with slightly different wording depending on the content area).

- Materials provide strategies and supports for students in special populations to support their regular and active participation in learning grade-level/series/grade-band mathematics.

- Materials provide strategies and supports for students in special populations to support their regular and active participation in learning grade-level/series/grade-band science and engineering.

- Materials provide extensions and/or opportunities for students to engage with grade-level/course-level/grade-band mathematics at higher levels of complexity.

- Materials provide extensions and/or opportunities for students to engage with grade-level/course-level/grade-band science and engineering at higher levels of complexity.

- Materials provide varied approaches to learning tasks over time and variety in how students are expected to demonstrate their learning with opportunities for students to monitor their learning.

- Materials provide opportunities for teachers to use a variety of grouping strategies.

- Materials provide strategies and supports for students who read, write, and/or speak in a language other than English to regularly participate in learning grade-level mathematics.

- Materials provide strategies and supports for students who read, write, and/or speak in a language other than English to regularly participate in learning grade-level science and engineering.

- Materials provide a balance of images or information about people, representing various demographic and physical characteristics.

- Materials provide guidance to encourage teachers to draw upon student home language to facilitate learning.

- Materials provide guidance to encourage teachers to draw upon student cultural and social backgrounds to facilitate learning.

- Materials provide supports for different reading levels to ensure accessibility for students.

__________________

NOTE: Review tools and criteria are available at https://www.edreports.org/process/review-tools

leaders become more aware of the trends across review tools and identify the elements that different groups think are necessary to embody culturally responsive instruction. The tools analyzed in the landscape study were of two types: (a) tools used to evaluate instructional resources for inclusion of culturally responsive practice and (b) tools used for informing instructional practice and for shifting mindsets.

The landscape analysis revealed that many of the tools do not provide clear direction for users on how to carry out a review of materials and using them to do a review requires a substantial time commitment. In most cases the collectors of evidence for the review are intended to be individual teachers to make their own informed decisions, or to inform the decisions of district leaders. The tools do not use common language to describe culturally responsive practice. In addition, the tools vary in how they identify equitable representation in materials. Eight of the 15 tools elevate support for multilingual learners, signaling the importance of addressing the needs of this population of students through language supports, accessibility measures, and cultural relevance in the materials that are used to teach them. Ten of the 15 tools include criteria related to student agency with some consistency across two primary areas: student choice or social justice.

These focused tools, used in concert with ratings from EdReports, have the potential to provide an approach to curriculum review and selection that includes a more explicit focus on equity and the equitable instructional practices discussed in Chapter 8. The additional tools also may help to identify curriculum materials that attend to elements of Frame 4 (using STEM to promote justice). See Box 10-3 for a list of selected resources and tools drawn from the EdReports landscape study that can be used to screen curriculum materials for a focus on equity and culturally responsive practice.

There are several widely used rubrics for evaluation of science and engineering instructional materials for adoption. The most commonly used of these are Educators Evaluating Quality Instructional Products (EQuIP), which is intended to be used to evaluate fully developed curriculum units, and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) lesson screener, for individual lessons; both are used to evaluate science and engineering instructional material for NGSS alignment and teacher support. These two tools most heavily take up Equity Frames 1 (reducing gaps between groups), 2 (expanding opportunity and access), and 3 (embracing heterogeneity) in their criteria for evaluation, and are mainly silent on Frames 4 (using STEM to promote justice) and 5 (envisioning sustainable futures). The NGSS lesson screener contains six criteria with 25 subcriteria. While the central purpose of the screener is to evaluate individual lessons on NGSS (and three-dimensional) alignment, there are a few criteria that specifically name connection to students’ questions, interest, and/or teacher support for connecting students’ questions to the rest of the lessons. For example,

BOX 10-3

Selected Tools and Resources for Selecting Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Instructional Materials

Additional Review Tools to Support the Selection of a High-Quality Curriculum in Rhode Island (Rhode Island Department of Education, 2020)a

Assessing Bias in Standards and Curricular Materials (Great Lakes Equity Center, 2017)b

Oregon Curriculum Adoption Selection Criteria (Eugene, Oregon)

For science (see Equitable Student Engagement and Cultural Pedagogy Criteria)c

For mathematics (see Equitable Student Engagement and Cultural Pedagogy Criteria)d

A Pathway to Equitable Math Instruction (Equitable Math, multiple authors, 2020)e

Questions to Ask While Evaluating Resources Featuring Indigenous, POC, and/or LGBTQ People and Communities (adapted by Queens University (Ontario, Canada) from Outreach Librarian (University of Toronto) Desmond Wong’s “Vetting Resources” presentation at the Symposium on The Importance of Indigenous Education in Ontario Classrooms (2018) and Dr. Cathy Gutierrez-Gomez’s “Tips for Choosing Culturally Appropriate Books and Resources About Native Americans” (2017)f

Social Justice Standards - The Teaching Tolerance Anti-Bias Framework (Teaching Tolerance/Southern Poverty Law Center, 2018)g

Tools and Guidance for Assessing Bias in Instructional Materials: Region 8 Comprehensive Center Network: Indiana, Michigan, Ohioh

__________________

a https://ride.ri.gov/instruction-assessment/curriculum#4379310-hqcm-review-tools

b https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED623049.pdf

c https://www.oregon.gov/ode/educator-resources/teachingcontent/instructional-materials/Documents/OregonScienceIMAdoptionCriteria2022_FINAL.pdf

d https://www.oregon.gov/ode/educator-resources/teachingcontent/instructional-materials/Documents/OR%20Math%20IM%20Criteria%202022_FINAL.pdf

f https://educ.queensu.ca/sites/educwww/files/uploaded_files/QuestionsToAskWhileEvaluatingResources_2020_FINAL.pdf

g https://www.learningforjustice.org/frameworks/social-justice-standards

the lesson screener looks for evidence that “the lesson provides support to teachers for making connections to the lives of every student in the class” (Frame 1) and that “student questions, prior experiences, and diverse backgrounds related to the phenomenon or problem are used to drive the lesson and the sense-making or problem-solving” (Frame 3).

EQuIP is a more comprehensive rubric, containing 19 criteria, including consideration of the opportunities students have to make sense of phenomena, the accuracy of the scientific content, relevance and authenticity of phenomena to students, coherence, and aspects of assessment. To illustrate the power that the EQuIP rubric holds in determining “high-quality” curriculum (e.g., alignment with NGSS as defined in the rubric): publicly available curriculum materials that earn a top EQuIP score from “elite cohort of educators from across the country” (who are trained and paid (through grant funding) to perform reviews) can earn an “NGSS design badge,” marking them as robust models of NGSS-aligned curricular materials. This badge is a clear marker that can be used by decision makers to ensure adoption of high-quality, NGSS-aligned curriculum materials.

Given the power of these rubrics for shaping curriculum at the state, district, and individual classroom levels, it is useful to understand how they do or do not take up the five equity frames and contrast them to another rubric, the Culturally Responsive-Sustaining STEAM Curriculum Scorecard (Peoples et al., 2021), that centers justice in evaluating STEAM curriculum (STEM with the addition of the arts) and most closely aligns with Frame 4 (using STEM to promote justice). The scorecard was developed to be used for K–12 curricula either in an individual STEAM discipline or in interdisciplinary STEAM curricula. The authors of the scorecard encourage diverse teams of evaluators (youth, parents, educators, administrators) to use it to determine the extent to which curricula are culturally responsive. The introduction states that “if STEAM curricula do not provide opportunities for culturally responsive and sustaining education, it cannot be high quality” (Peoples et al., 2021, p. 3). The scorecard encourages a reflection on the diversity of the review team, including racial makeup and (dis)abilities.

The Culturally Responsive-Sustaining STEAM Curriculum Scorecard evaluates STEAM curricular materials along four major dimensions: (a) representation, (b) social justice, (c) teacher materials, and (d) material/resources. Rather than simply stating the evidence for each dimension, the scorecard encourages evaluators to record “Attempts” (evidence) and “Are the attempts problematic?” to account for the ways in which cultural relevance can be taken up as tokenism, saviorism, cultural appropriation, or in other problematic ways (Rodriguez, 2021). In addition, the scorecard encourages an examination of the diversity of the authors of the curriculum, if the curriculum materials encourage teachers becoming aware of their own biases, and if the materials include guidance for teachers to “combat the

legacy of STEAM education related trauma amongst historically marginalized communities and on designing healing and joyful STEAM experiences” (p.16) and “presents social situations and problems not as individual problems but as embedded within a societal and/or systemic context” (p. 12). In this way, the scorecard encourages a vision of STEAM education that implicates the five frames presented in Chapter 6 to varying degrees.

The absence of attention to issues of equity and justice in evaluating instructional materials also matters for resources that state departments of education put toward professional development and the types of contracts that districts have to aid in the purchase of new materials. For example, in Louisiana, materials that are rated as “top tier” can be purchased by districts under a state contract, but lower-tier materials are not eligible for the state contract (NASEM, 2022, p. 171). The state department of education will also offer free professional development for top-tier adopted materials, but not for others. Using these levers at the state level foregrounds the importance of considering the extent to which these rubrics capture key dimensions of equity, power, and justice, as is the case currently in both Oregon and Rhode Island. Increasingly, states and districts are looking for open access curriculum materials so that they can have more funds to devote to teacher professional development and purchasing instructional materials (NASEM, 2018).

The five frames for equity articulated in Chapter 6 were based in the literature that can lead to meaningful STEM learning. These five frames can be used to extrapolate a set of guiding questions that leaders can look for to critically examine STEM curricula for how they attend to STEM learning through an equity lens (Table 10-2).

Designing in Partnership with Families and Communities

Intentionally designed instructional materials can situate STEM learning within the cultural lives and communities of students and families (Tzou et al., 2021). By offering new models of relationships between teachers, families, and communities, instructional materials can support teachers in partnering with families for joint decision making over learning in the classroom, designing intergenerational learning opportunities (Bang et al., 2016).

Increasingly, researchers, non-dominant families, and schools are partnering to address “racialized and asymmetrical power dynamics” of schooling (Ishimaru et al., 2018). This practice of participatory co-design (Bang & Vossoughi, 2016), or community-engaged design (Ishimaru et al., 2018) rests on critical examination how racialized power dynamics that were established in the past are perpetuated by continuing the status quo, or “doing things the way we’ve always done them.” In this way, non-dominant families

TABLE 10-2 Guiding Questions for Curriculum Materials Based on Equity-Focused Approaches to Learning

| Equity-focused approaches to learning | Questions to ask of curricular materials |

|---|---|

| Asset-based: all learners have sensemaking resources to draw from; this counteracts deficit views of students, their families, and communities. These sensemaking approaches also stem from historicized relationships that families and communities have with science, the disciplines, and schooling. |

|

| Sociocultural: emphasizes the cultural nature of learning; learning happens across varied settings; de-settling white, middle-class norms against which all others are measured; teaching and learning deeply connected to students’ lives, identities, and ways of being. |

|

| Attending to epistemic heterogeneity as foundational to learning. |

|

| Expansive visions of the disciplines |

|

| Equity-focused approaches to learning | Questions to ask of curricular materials |

|---|---|

| Cultivating joy and agency |

|

SOURCE: Committee generated.

not only “share” their experiences, wishes, and dreams for the future but lead those efforts with true agency—in partnership with researchers, school leaders, and others (Ishimaru, 2018). While there are few examples of this kind of co-design in science and engineering, research has shown the role that non-dominant families can play in changemaking in literacy education (Delgado-Gaitin, 1994) and mathematics learning (Ishimaru et al., 2015).

There are also increasing examples that show that families as intergenerational learning units bring rich sensemaking repertoires to learning environments, where learners’ intersecting identities, family and community histories, linguistic practices, and family values are key dimensions of learning (Bang et al., 2018; Tzou et al., 2019, 2020). Curricular materials that draw on this body of research create porous learning environments where family ways of knowing, being, and doing in STEM flow from home to school and help teachers make localized instructional decisions (Tzou et al., 2021).

A specific example of a curriculum tool that supports teachers in this work is self-documentation (Tzou et al., 2010), a strategy with origins in anthropology (Clark-Ibañez, 2004) that allows students and families to document their family and cultural ways of knowing, being, and doing in relation to a provided prompt. For example, in the Micros and Me project (Tzou & Bell, 2010), fifth-grade teachers sent home the self-documentation prompt of “How does your family keep healthy and keep from getting sick?” Research found that initial responses from students and families fell within dominant health and science narratives of germ prevention, washing hands, and getting sleep. However, after teachers modeled their own cultural practices around staying healthy, students’ and families’ subsequent responses were more varied (drinking Mangosteen, drinking tea, growing plants in the garden, etc.; Tzou & Bell, 2010). Self-documentation has been taken up in numerous examples as a way to routinely connect to students’

and families’ knowledges and practices in both classroom instruction and as formative assessment (Ashbrook, 2021; Bricker et al., 2014; National Research Council, 2014).

Sustained, intentional partnerships can support the design and implementation of equitable STEM curriculum. Partnerships between teachers and curriculum designers can be key in supporting teachers to meet the diverse needs of their students through professional development (NASEM, 2018). This can be even more true when teachers come into the practice of addressing issues of race and culture in STEM teaching. One kind of partnership that can support new approaches to expanding equity in STEM is Research-Practice Partnerships (RPPs). RPPs have the following five characteristics: (a) they are long term, (b) they are focused on mutually defined problems of practice, (c) they are mutualistic, (d) they are intentionally organized, and (e) they produce original analyses (Coburn et al., 2013; Farrell et al., 2021). These types of partnerships can involve school district-university researchers to connect high school curriculum with students’ interests (Penuel et al., 2022), Indigenous community organizations, tribes, and university researchers (Bang et al., 2010), or using ecosystems strategies involving multiple agencies and actors within a given community to diversify the educational opportunities within a learning ecosystem (Santo et al., 2017). Given the complexities of addressing issues of equity in STEM education along multiple axes, research-practice partnerships offer a promising approach if the partnership itself explicitly addresses underlying causes of persistent inequities (Penuel, 2017). Research-practice partnerships do not always result in designed curriculum materials—the outputs of RPPs depend on the mutually defined problems of practice and the ways that the partnership decides to address them.

Research has shown that strong family and community ties are key to school improvement (Bryk, 2010), and that family engagement can have a positive impact on disciplinary learning (Epstein & Sheldon, 2016). The recently released National Academies report on science and engineering in preschool through fifth grade (NASEM, 2022) concluded that “families are essential partners in the learning of science and engineering in preschool through elementary grades” (p. 239) and recommend that “preschool and elementary school leaders and teachers should engage and collaborate with families and local community leaders to mutually support children’s opportunities for engaging in science and engineering […] to design learning experiences that are meaningful and relevant to children” (pp. 246–247). Foregrounding families and communities in the design of instructional materials provides a unique opportunity to support learners in their unique contexts, enabling the kinds of expansive learning experiences described earlier in this report. Although this strategy is not unique in its ability to support the development of high-quality instructional materials, it offers

promise as one approach toward addressing multiple of the five equity frames at once. By engaging in co-design opportunities, instructional materials developed in partnership can support greater access to STEM education for multiple groups, as well as engage with nondominant perspectives in STEM.

TIME AND RESOURCES

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, high-quality instructional materials alone are not enough to address the considerable inequities in STEM education. In order to implement instructional materials effectively and robustly, educators need devoted time for planning and implementation, the physical resources necessary to do the job, and opportunity to engage in supportive professional development. Therefore, there is also a need to address the various structural issues that prevent educators from accessing and engaging with these implementation supports. In this section, we first discuss these inequities in depth, and then turn to an additional discussion of how decision makers can address them.

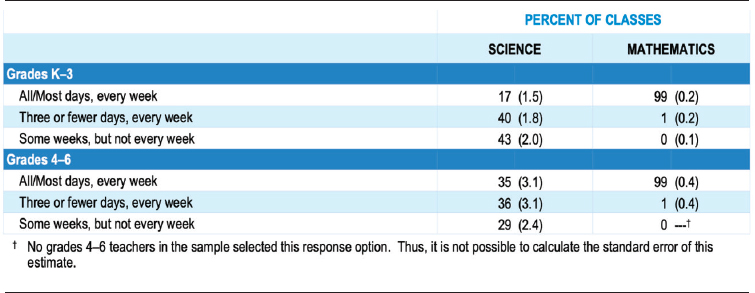

We turn first to the issue of time. Data from the 2018 NSSME+ shows that, in elementary school in particular, there are limited opportunities to engage in science as compared to mathematics and literacy (see Table 10-3). Of the K–3 classes surveyed, 43 percent teach science some weeks, but not every week. In grades 4–6, only 35 percent of classrooms teach science all or most days of the week, every week. This is especially true in schools with high accountability pressures (usually in communities with high concentrations of students living in poverty and students of color; Penuel, 2017; Rodriguez, 2015). This paucity of time devoted to science in elementary has particular consequence for students’ success in science later in their academic trajectories, as early engagement with science helps sustain students’ natural enthusiasm for science and builds the foundation for the knowledge and skills they need to approach the more challenging topics introduced in later grades (NASEM, 2022).

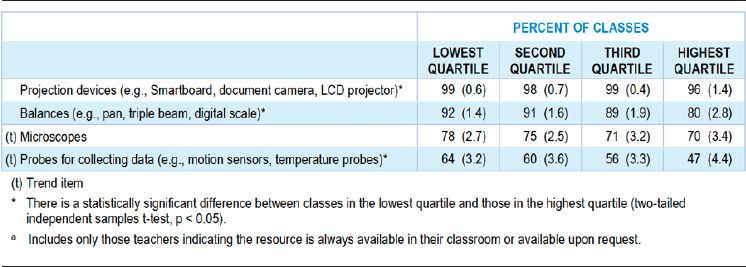

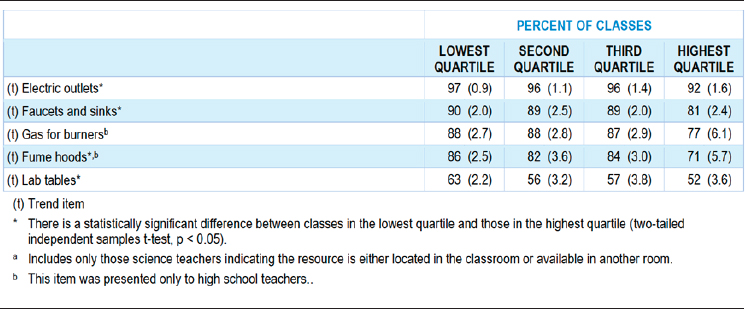

Beyond inequities in time, material resources are a critical component of effectively implementing instructional materials. In science, implementation requires access to a series of physical resources, as well as the professional knowledge of how to use them. These materials include standard classroom resources such as projection devices, balances, microscopes, and other tools. However, for the kind of laboratory investigations called for in later grades, classrooms require a much broader suite of materials, including outlets, faucets, gas for burners, etc. In Tables 10-4 and 10-5, the 2018 NSSME survey data demonstrate how these materials are inequitably distributed across schools with differing percentages of students from demographic backgrounds historically underrepresented in STEM fields.

Put another way, schools with higher percentages of students of color are significantly less likely to have access to the kinds of materials necessary to achieve the vision laid out in the Next Generation Science Standards or similarly robust state-level science standards.

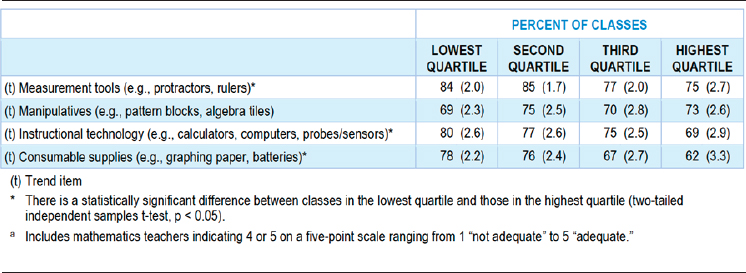

This same lack of access is true in mathematics. Although mathematics does not require access to the same level of resourcing that science does, measurement tools and manipulatives are still central to implementing instructional materials effectively. Table 10-6 shows that schools with higher percentages of students of color are less likely to have access to the kinds of material resources called for in contemporary mathematics instruction.

These inequities in material resources underscore the ways that inequity shows up in multiple parts of the education system. Even if teachers are adequately prepared to engage in equitable STEM instruction, lack of access to instructional materials and the time and resources will inevitably frustrate any efforts to achieve equitable STEM education. By the same token, access to these materials is not enough: as previous sections of this chapter note, unless teachers have the time and space to effectively engage with instructional materials and the resources that should accompany them, they are unlikely to take up newer, more equity-oriented approaches in their instruction. The issue of availability of technological resources, for example, frustrates the notion that access is enough (see Box 10-4).

Decision makers at all levels have a role to play in addressing these inequities. As evidenced in the technology example above, providing money for access to materials is not enough: decisions need to be made at all levels of the system to align multiple aspects of STEM to high-quality instructional materials. Instructional materials designers and developers can engage multiple strategies for ensuring resulting products are getting at expansive visions of equity described throughout this report. As we

TABLE 10-6 Adequacya of Resources for Mathematics Instruction, by HUS Quartile

SOURCE: Banilower et al. (2018).

BOX 10-4

Technological Resources: Why Access Is Not Enough to Achieve Equity

In the wake of the rapid closure of in-person schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of U.S. schools were compelled to make an immediate shift to online education. The pace of this unprecedented shift revealed the extent of the “Digital Divide”—a substantial gap in access to technological resources between well-resourced and underserved schools and communities. Less affluent schools and communities were less likely to have the necessary infrastructure (broadband internet, personal computing devices, online education platforms, etc.) to provide high-quality educational experiences for their students, while other communities switched to the new model with relatively few frustrations.

Increased attention to the extent of the divide ushered in the formation of technological access funding opportunities at all levels of government as well as in the private sector. In the aftermath of the pandemic, the gap in access to education technology of all kinds has narrowed, but equity issues persist. Even prior to the pandemic, in fact, researchers have long observed that access alone cannot solve pernicious problems related to technology and education (see, e.g., Means, 1994; Means et al., 2003). Reich and Ito (2017) identified the following ongoing concerns:

- Same Technology, Unequal Schools: The push for educational technology has meant that more young people across the socioeconomic spectrum in the United States have access to learning technologies through their schools. Even when the playing field is leveled for technology access, however, inequities persist. Schools serving privileged students tend to use the same technologies in more progressive ways than schools serving less privileged students.

- Open ≠ Equitable: Ubiquitous digital devices and online networks have radically reduced costs for accessing online and digital learning. As intuitive as the idea sounds, however, free and open technologies do not democratize education. In fact, evidence is mounting that free online learning materials disproportionately benefit the affluent and highly educated.

- Social and Cultural Forces Derail Good Intentions: New technologies are taken up in varied and unexpected ways by diverse learners and in diverse settings. Once technological and economic barriers are removed, broader

- social and cultural forces determine outcomes. Efforts to democratize education through technology have often faltered because technologists failed to anticipate broader social and cultural forces. Unintended outcomes commonly grow out of two underlying social and cultural forces: institutionalized and unconscious bias and social distance between developers and those they seek to serve.

The U.S. Department of Education reinforced these concerns in the 2024 National Educational Technology Plan, which makes recommendations for states and districts along three axes:

- Digital Use Divide: Inequitable implementation of rich, cognitively demanding instructional tasks supported by technology. On one side of this divide are students who are asked to actively use technology in their learning to analyze, build, produce, and create using digital tools, and, on the other, students encountering instructional tasks where they are asked to use technology for passive assignment completion. While this divide maps to the student corner of the instructional core, it also includes the instructional tasks drawing on content and designed by teachers.

- Digital Design Divide: Inequitable access to time and support of professional learning for all teachers, educators, and practitioners to build their professional capacity to design learning experiences for all students using educational technology. This divide maps to the teacher corner of the instructional core.

- Digital Access Divide: Inequitable access to connectivity, devices, and digital content. Mapping to the content corner of the instructional core, the digital access divide also includes equitable accessibility and access to instruction in digital health, safety, and citizenship skills.

In this way, the committee observes that access to technology alone cannot solve an equity challenge. Indeed, as noted in the Reich and Ito (2017) piece, introducing technology across the board actually increases inequities, as well-resourced schools are better positioned to onboard new technology and support educators in learning how to effectively engage with new tools. Rather than leveling the playing field, introducing technology into an already inequitable system without addressing exisiting structural issues merely reproduces (and potentially exacerbates) ongoing challenges.

describe above, decision makers responsible for designing and implementing professional development can support educator confidence and facility with instructional materials; state, district, and school leaders can ensure that educators are supported in engaging with that professional learning.

CONCLUSIONS

Instructional materials have the potential to bring more equitable learning opportunities in STEM, but many current materials available may prioritize Western ways of knowing, being, and doing while also diminishing ways of knowing seen among students of color and other groups marginalized in STEM. Educators try to utilize different types of materials in their classrooms or programs, but several educators acknowledge that the ultimate decision of which curriculum they must use in the classroom is often made at the district level, especially for STEM subjects. Further, some of those materials chosen for science and math courses are outdated and do not reflect the constantly changing world today, which hinders students’ knowledge and future learning. Finally, the way educators use the instructional materials is dependent on the educator’s own sensemaking and ways of knowing, which can exacerbate inequities in STEM learning.

Instructional materials can be designed to center equity and justice, but families and communities should also be involved in the design process to ensure that the materials created accurately tie in different cultures and ways of knowing to ensure that students have the opportunity to learn and understand STEM concepts in ways that are relevant to their surrounding lives. As these materials are created, leaders in school districts and other decision makers wary about changing or adopting new curriculum can take advantage of utilizing some rubrics like EQuIP or the Culturally Responsive-Sustaining STEAM Curriculum Scorecard to identify how many equitable learning opportunities are being introduced in STEM courses within their districts.

Conclusion 10-1: Instructional materials are developed within an inequitable education system that traditionally privileges particular forms of STEM disciplinary knowledge. At the same time, experiences in school, mediated by instructional materials, are often the first and only way that individuals are introduced to STEM. As a result, instructional materials can play a key role in either reinforcing narrow conceptions of the STEM disciplines or introducing more expansive conceptions.

Conclusion 10-2: Development, adoption, and implementation of STEM instructional materials takes place within and across the multiple levels of the U.S. education system. Decisions made throughout

these processes have implications for how students experience STEM learning, what content is prioritized, and whether students’ identities and experiences outside of school will be recognized and leveraged as assets.

The next chapter turns to pathways that influence what students do with their STEM learning and connects how various learning methods, the ways educators teach, and the instructional materials described in this chapter all converge on a student’s trajectory to receive equitable STEM learning.

REFERENCES

Arias, A. M., Bismack, A. S., Davis, E. A., & Palincsar, A. S. (2016). Interacting with a suite of educative features: Elementary science teachers’ use of educative curriculum materials. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 53(3), 422–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21250

Ashbrook, P. (2021). Culturally responsive teaching breadcrumb. Science and Children, 58(4).

Bang, M., Faber, L., Gurneau, J., Marin, A., & Soto, C. (2016). Community-based design research: Learning across generations and strategic transformations of institutional relations toward axiological innovations. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 23(1), 28–41.

Bang, M., Marin, A., & Medin, D. (2018). If Indigenous peoples stand with the sciences, will scientists stand with us? Daedalus, 147(2), 148–159.

Bang, M., Medin, D., Washinawatok, K., & Chapman, S. (2010). Innovations in culturally based science education through partnerships and community. In M. S. Khine & I. M. Saleh (Eds.), New science of learning: Cognition, computers and collaboration in education (pp. 569–592). Springer.

Bang, M., & Vossoughi, S. (2016). Participatory design research and educational justice: Studying learning and relations within social change making. Cognition and Instruction, 34(3), 173–193.

Bang, M., Warren, B., Rosebery, A., & Medin, D. (2012). Desettling expectations in science education. Human Development, 55, 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345322

Banilower, E. R., Smith, P. S., Malzahn, K. A., Plumley, C. L., Gordon, E. M., & Hayes, M. L. (2018). Report of the 2018 NSSME+. Horizon Research, Inc.

Bricker, L. A., Reeve, S., & Bell, P. (2014). ‘She has to drink blood of the snake’: Culture and prior knowledge in science | health education. International Journal of Science Education, 36(9), 1457–1475.

Bryk, A. S. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 91(7), 23–30.

Clark-Ibañez, M. (2004). Framing the social world with photo-elicitation interviews. Behavioral Scientist, 47(12), 1507–1527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764204266236

Coburn, C. E., Penuel, W. R., & Geil, K. E. (2013). Practice partnerships: A strategy for leveraging research for educational improvement in school districts. William T. Grant Foundation.

Council of Chief State School Officers. (2023). Impact of the CCSSO IMPD Network. https://753a0706.flowpaper.com/CCSSOIMPDImpactUpdate11923/#page=1

Davis, E. A., Janssen, F. J. J. M., & van Driel, J. H. (2016). Teachers and science curriculum materials: Where we are and where we need to go. Studies in Science Education, 52(2), 127–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2016.1161701

Davis, E. A., & Krajcik, J. S. (2005). Designing educative curriculum materials to promote teacher learning. Educational Researcher, 34(3), 3–14.

Davis, E. A., Palincsar, A. S., Smith, P. S., Arias, A. M., & Kademian, S. M. (2017). Educative curriculum materials: Uptake, impact, and implications for research and design. Educational Researcher, 46(6), 293–304. https://doi.org/0.3102/0013189X17727502

Delgado-Gaitan, C. (1994). Sociocultural change through literacy: Toward the empowerment of families. In B. M. Ferdman, R. M. Weber, & A. G. Ramírez (Eds.), Literacy across languages and cultures (pp. 143–169). State University of New York Press.

EdReports. (2022). Evaluating materials for culturally responsive practices: A landscape analysis. https://cdn.edreports.org/media/2022/09/Landscape_Analysis_1022.pdf?_gl=1*170e0te*_gcl_au*MTg2MTE3OTE0OS4xNzE1MDkyMzQ4

Epstein, J. L., & Sheldon, S. B. (2016). Necessary but not sufficient: The role of policy for advancing programs of school, family, and community partnerships. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(5), 202–219.

Farrell, C. C., Penuel, W. R., Coburn, C. E., Daniel, J., & Steup, L. (2021). Research-practice partnerships today: The state of the field. National Center for Research in Policy and Practice.

Ishimaru, A. M. (2018). Re-imagining turnaround: Families and communities leading educational justice. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(5), 546–561.

Ishimaru, A. M., Barajas-López, F., & Bang, M. (2015). Centering family knowledge to develop children’s empowered mathematics identities. Journal of Family Diversity in Education, 1(4), 1–21.

Ishimaru, A. M., Rajendran, A., Nolan, C. M., & Bang, M. (2018). Community design circles: Codesigning justice and wellbeing in family-community-research partnerships. Journal of Family Diversity in Education, 3(2), 38–63.

Kaufman, J. H., Doan, S., & Fernandez, M.-P. (2021). The rise of standards-aligned instructional materials for U.S. K–12 mathematics and English language arts instruction: Findings from the 2021 American Instructional Resources Survey. RAND. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA134-11.html.

Means, B. (Ed.). (1994). Technology and education reform: The reality behind the promise. Jossey-Bass.

Means, B., Roschelle, J., Penuel, W. R., Sabelli, N., & Haertel, G. D. (2003). Technology’s contribution to teaching and policy: Efficiency, standardization, or transformation? Review of Research in Education, 27, 159–181. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X027001159

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). (2018). Design, selection, and implementation of instructional materials for the Next Generation Science Standards: Proceedings of a workshop. National Academies Press.

___. (2022). Science and engineering in preschool through elementary grades: The brilliance of children and the strengths of educators. National Academies Press.

National Research Council. (2014). Developing assessments for the Next Generation Science Standards. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18409

NextGen Science, Next Generation Science Standards, & EdReports. (2021). Critical features of instructional materials design for today’s science standards. WestEd and EdReports. https://www.nextgenscience.org/sites/default/files/CriticalFeaturesInstructionalMaterials_July2021.pdf?_ga=2.209047451.848799520.1724786424-383454984.1724786424

Penuel, W. R. (2017). Research–practice partnerships as a strategy for promoting equitable science teaching and learning through leveraging everyday science. Science Education, 101(4), 520–525.

Penuel, W. R., Allen, A.-R., Henson, K., Campanella, M., Patton, R., Rademaker, K., Reed, W., Watkins, D. A., Wingert, K., Reiser, B. J., & Zivic, A. (2022). Learning practical design knowledge through co-designing storyline science curriculum units. Cognition and Instruction, 40(1), 148–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2021.2010207

Peoples, L. Q., Islam, T., & Davis, T. (2021). The culturally responsive-sustaining STEAM curriculum scorecard. Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools, New York University.

Reich, J., & Ito, M. (2017). From good intentions to real outcomes: Equity by design in learning technologies. Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Rodriguez, A. J. (2015). What about a dimension of engagement, equity, and diversity practices? A critique of the next generation science standards. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(7), 1031–1051.

___. (2021). How to avoid seven common (but seldom discussed) STEM curriculum pitfalls: Making STEM more culturally and socially relevant. Multicultural Perspectives, 23(4), 224–231.

Rosebery, A. S., & Warren, B. (Eds.). (2008). Teaching science to English language learners: Building on students’ strengths. NSTA Press.

Santo, R., Ching, D., Peppler, K., & Hoadley, C. (2017). Messy, sprawling and open: Research-practice partnership methodologies for working in distributed inter-organizational networks. In B. Bevan & W. R. Penuel (Eds.), Connecting research and practice for educational improvement: Ethical and equitable approaches (pp. 100–118). Routledge.

Steiner, D. (2017). Curriculum research: What we know and where we need to go. Standards Work.

Tzou, C., Bang, M., & Bricker, L. (2021). Commentary: Designing science instructional materials that contribute to more just, equitable, and culturally thriving learning and teaching in science education. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 32(7), 858–864.

Tzou, C., Meixi, Suárez, E., Bell, P., LaBonte, D., Starks, E., & Bang, M. (2019). Storywork in STEM-Art: Making, materiality and robotics within everyday acts of indigenous presence and resurgence. Cognition and Instruction, 37(3), 306–326.

Tzou, C., Scalone, G., & Bell, P. (2010). The role of environmental narratives and social positioning in how place gets constructed for and by youth. Equity & Excellence in Education, 43(1), 105–119.

Tzou, C., Suárez, E., Bell, P., LaBonte, D., Starks, E., & Bang, M. (2020). Storywork in STEM-Art: Making, materiality and robotics within everyday acts of indigenous presence and resurgence. In T. Sengupta-Irving & M. McKinney de Royston (Eds.), STEM and the social good (pp. 30–50). Routledge.

Tzou, C. T., & Bell, P. (2010). Micros and Me: Leveraging home and community practices in formal science instruction. In K. Gomez, L. Lyons, & J. Radinsky (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (pp. 1135–1143). International Society of the Learning Sciences.

This page intentionally left blank.