Assessing Research Security Efforts in Higher Education: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 3 Research Security Policies and Requirements: Scope and Measures of Effectiveness

3

Research Security Policies and Requirements: Scope and Measures of Effectiveness

McQuade moderated a panel that discussed how to measure the effect of research security policies and requirements. He reiterated that the overall goal of the workshop was to examine the effectiveness of efforts to protect national security in the operation of federally funded research at universities. He also noted that that the previous session provided context for an examination of the DOD research security ecosystem and the broader research ecosystem and said that the intention of the current panel was to consider how security outputs are to be measured or could be measured, the effectiveness of controls, and the impact of controls on the outputs of the U.S. research enterprise.

The first panelist, Tam Dao (Rice University), discussed how Rice approaches research security. He said that the university’s goal in its research security efforts is to safeguard the means, know-how, and products that originate from its research ecosystem. This requires awareness, education, training, foreign influence risk assessment, and strong partnerships. Dao suggested that many in academia are unaware of research security threats.

Research security programs at Rice emphasize awareness, education, and training. The university’s research security training focuses on foreign influence, Dao said. While there are many training programs available, he noted that effective training allows researchers to develop skills for identifying the best approaches for addressing potential research security risks.

Dao emphasized the importance of partnerships in research security. Rice University works closely with federal partners on research security.

He described an initiative where the FBI held classified briefings where individuals from the academic sector could provide input on (and provide examples of) research security issues of concern. In a manner similar to academic peer review, this allowed the agency to solicit expert input and feedback.

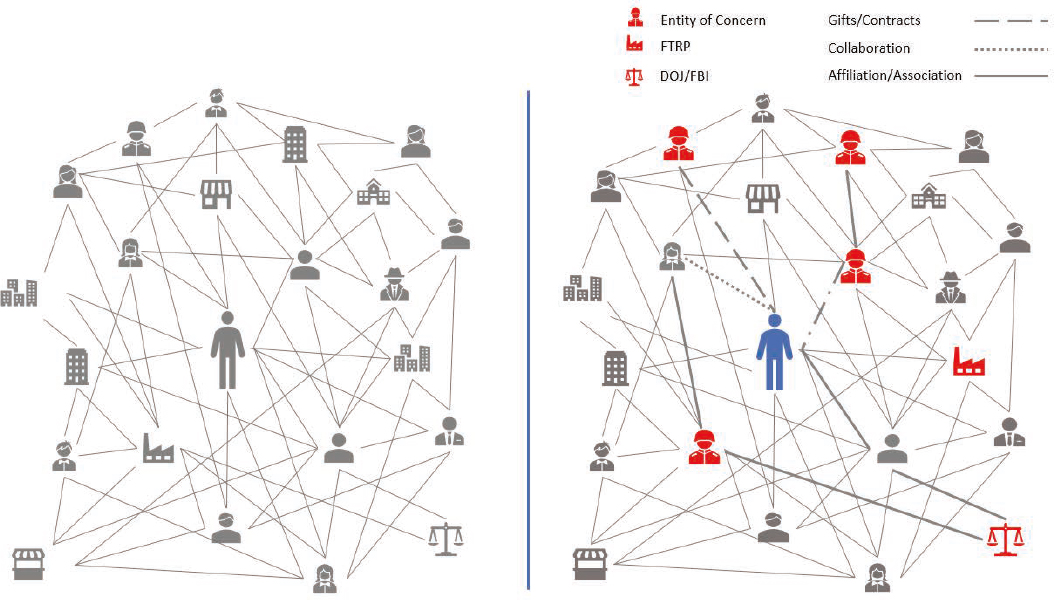

Dao discussed the university’s work on foreign influence risk assessment. As faculty engage in many types of relationships, whether as part of a collaboration, partnership, or engagement with a visiting scientist, it can be complicated for them to navigate research security issues (see Figure 3-1). Faculty may not, for example, be sensitized to the possibility that their contacts are subject to foreign influence.

When it comes to research security, assessing risk is complicated, Dao said. There are no mathematical formulas to assess research security risk, and to be successful, he continued, a research security program must ensure that faculty have access to the information they need to make well-informed decisions about risks.

The second panelist, Elisabeth Paté-Cornell (Stanford University), discussed her work in risk analysis and scenarios, probabilities, and outcomes related to research security. She said that a consideration of uncertainty is particularly important for research security as nothing can be known for certain except what has been observed directly. In considering risks related to research security, Paté-Cornell said that it is important to consider

- Who are the adversaries, what do they want, what might they get, how might they get it?

- What can adversaries do with what they get and how will it affect U.S. security and defense in particular?

- What can be done to prevent misappropriation?

- How effective are current research security methods?

- How can we improve them?

- What are the expected results?

Paté-Cornell said her interest is in what a technology will do in a conflict and what will be the effect. To assess risk, Paté-Cornell said that we should consider which technologies are most critical to U.S. national and economic security. These may include semiconductors, quantum computing, AI, bioengineering, nuclear engineering, and manufacturing methods. A next step would be to consider the potential utility of these technologies to Chinese industry and defense. It is particularly important, she said, to consider which technologies can be leveraged in conflicts as this can be helpful in identifying potential areas of risk.

SOURCE: Tam Dao, Associate Vice President, Campus Safety and Research Security and Baker Institute Rice Faculty Scholar, Rice University. May 22, 2025, Workshop Presentation.

Paté-Cornell said that it is important to consider how to protect research in instances where the United States leads in industry and academia. She suggested that, to support research security efforts, research results related to critical technologies need to be identified, classified if necessary, and potentially have controls on their publication.

Risk analysis requires examining where critical problems arise, Paté-Cornell asserted. In one scenario, she noted, the Chinese conducted cyberattacks on U.S. quantum computing centers. These attacks carried significant security risks, slowed U.S. technology development, and had an adverse effect on U.S. military operations.

Panelist Sarah Stalker-Lehoux (NSF) said that the ideal measure of the effectiveness of research security programs would be reducing undue foreign interference in the U.S. research ecosystem. For Stalker-Lehoux, the question is how to reduce interference while also encouraging international collaboration. She said that, for national security reasons, it is critical that the United States remain the top science and technology destination in the world.

Stalker-Lehoux said that, while it may be possible to measure the effectiveness of research security policies, the U.S. research ecosystem is currently at a stage of implementing research security requirements.

Stalker-Lehoux said that cybersecurity is an important aspect of research security programs. In the fundamental research space, it is critical to establish cybersecurity standards. She said that the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has a research security program that uses a risk-based methodology to assign security countermeasures to adequately safeguard the agency’s scientific research and IP. However, Stalker-Lehoux suggested that there is a need for more input from others in the scientific community on cybersecurity measures.

Stalker-Lehoux emphasized the importance of human capital and talent in discussions of research security. NIST will be working with the National Academies’ Federal Demonstration Partnership (FDP)1 and EDUCAUSE2 to assess human-capacity needs for research security. “Along the

___________________

1 The FDP “is an association of federal agencies, research policy organizations and academic research institutions with administrative, faculty and technical representation.” Its “mission is to streamline the administration of federally sponsored research and create resources that are available to the research enterprise regardless of membership status.” See https://thefdp.org.

2 EDUCAUSE is a is a nonprofit association whose mission is to advance the strategic use of technology and data to further higher education. See https://www.educause.edu.

way, through constant engagement and dialogue, we can continue to . . . pivot.” But the ultimate goal is to develop “standards of measurement and success,” she said.

While recognizing that it is hard to measure, Stalker-Lehoux said that increased awareness of research security could be a sign of the effectiveness of research security policies and requirements. She suggested that counting the number of research security trainings completed could be a way to gauge awareness. She cautioned, however, that it is not clear whether training is effective or sufficient.

Stalker-Lehoux said that researchers must understand the importance of openness and transparency in research. “These are the fundamental values that we all aspire to achieve in our research,” she said, “but we have to be cognizant that the landscape has changed.” She noted, for example, that researchers have been coerced by adversarial governments into sharing research.

Stalker-Lehoux said that building awareness about research security is a responsibility of the agencies funding research. NSF recently instituted a review process for proposals to assess active appointments and research funding to identify institutions that might pose a research security risk. Stalker-Lehoux suggested that, if researchers decline to collaborate with foreign institutions that do not pose a risk, this will reduce our scientific and technological advantage.

Stalker-Lehoux said that research security “is a shared responsibility. We can’t do it on our own. And empowering everyone to have the tools that they need and the knowledge that they need to say, ‘Okay, this is the amount of risk in the situation, but it’s okay, I’m going to be risk tolerant’ or ‘This is too much risk.’”

Stalker-Lehoux said that, while NSF funds 45,000 proposals annually, its research security unit has the capacity only to closely review quantum information science and some AI and dual-use research of concern-related proposals. Awareness-building and empowering institutions to support researchers in research security is critical, as is mitigating risk. The more that can be done to support those in the community that might be attracted to participate in foreign talent programs, the better.3 This includes equipping them with information and resources.

___________________

3 Foreign talent programs are initiatives that are organized, managed, or funded by a foreign government or entity for the purpose of recruiting subject matter experts. These programs often involve compensation for individual researchers in exchange for specific research activities or obligations that may create risks for the U.S. research enterprise.

Panelist Steven H. Walker (Lockheed Martin [retired]) noted that the global strategic environment has changed over the last 5–10 years, as the United States has moved toward military and economic competition with several peer adversary nations, particularly China.

Walker said that the PRC’s spending on R&D grew from $14 billion in 1996 to about $670 billion in 2021 and that China is making significant investments in technology development. He noted that China uses technology for illicit purposes, such as to assist in the acquisition of foreign technologies.

Walker said that NSPM-33 was a good step forward and that the CHIPS and Science Act was helpful “in identifying at least a list of technologies that we need to be concerned about.”4

The use of uniform disclosure forms across federal agencies helps to scale research security efforts consistently across agencies. Walker said that clear standards for research security training on cybersecurity, expert control, and foreign travel security are important. Eliminating conflicts of interest with foreign governments and ensuring that researchers understand conflicts of interest is a must.

Walker said that, while industry has largely been absent from conversations about research security, it could be a strong partner. Lockheed Martin and other industry partners have initiatives that evaluate the sensitivity of research awards to universities and consider whether the research is in an area targeted by foreign adversaries. Hypersonics is one example of a targeted research area; Lockheed Martin works to ensure that any hypersonics research is conducted by trusted researchers. The company gives particular scrutiny to research projects that involve proprietary information. The company also trains employees who work with university researchers.

Conversations about research security have mostly been between government and universities, Walker said, but industry should be more

___________________

4 The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (Public Law No. 117-167) includes several provisions aimed at enhancing research security across U.S. science and technology sectors. For example, the Act mandates that NSF maintain an Office of Research Security and Policy within the Office of the NSF Director, prohibits participation in foreign talent recruitment programs that pose a threat to U.S. research security, and requires that institutions receiving federal research funding provide training on research security for all covered personnel. Furthermore, the Act mandates the creation of a Research Security and Integrity Information Sharing and Analysis Organization to facilitate the sharing of information related to research security threats and best practices among research institutions. It also tasks NSF with developing an online resource containing up-to-date information tailored for institutions and individual researchers to support compliance with research security requirements as well as a program to support research on research security.

involved. “The more the government . . . can bring in industry to help with [research security] the better,” he said. The connection to industry is critical for assessing the vulnerabilities of basic research

Walker noted that allowable university overhead reimbursement rates are decreasing while government compliance requirements, including research security–related compliance requirements, are increasing. This is not sustainable, he said.

Walker said the university culture will need to change for research security to become a campus priority. “If you’re going to be secure and protect information you’re going to have to” change “culture and mindset,” he said.

Walker said that the line between fundamental and applied research needs to be clearer. Security is important, but fundamental science should not be inhibited. “We do not want to slow down this engine of ingenuity and innovation,” he said. More consideration is needed of how parties can work together to provide a secure environment for technological development.

DISCUSSION

McQuade asked Walker to comment on how current research security programs and policies build on earlier policies.

Walker said that the whole ecosystem has changed over time. Universities now play a more significant role in technology areas that are critical to national security, and there is a need to step back and consider research security in this new environment. He said that if universities are conducting applied research important to national security, it may be necessary to conduct such research at a secure facility or institute that can carefully vet researchers. He suggested that fundamental research should be conducted in unrestricted environments so that it may flourish as it always has. Paté-Cornell added that the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board5 and the Army Science Board6 could also contribute to conversations about the performance of applied and fundamental research as they often act as intermediates between universities and the larger ecosystem.

Nichols asked how, if research is not restricted, the U.S. government would have institutions protect open fundamental research that ultimately will be published. Research institutions are not trying to restrict fundamental research, she said, but there are concerns about leakage in the fundamental research space. Walker suggested separating out fundamental

___________________

5 See https://www.scientificadvisoryboard.af.mil/.

6 See https://asb.army.mil/.

research but identifying technology areas and research that can easily be moved into applied research.

McQuade said that the National Academies recently published a report that examined the protection of technologies that have strategic importance for national security.7 The report raised a question about whether it is possible to conduct both open and restricted research simultaneously on university campuses. He said that, in many instances, academic institutions elect not to conduct sensitive research.

McQuade asked Dao and Stalker-Lehoux about measuring the effectiveness of research security policies and the data needed to do so. Dao said that Rice University has about 300 faculty and a team of five focused on research security. For Rice, one measure of effectiveness is the number of times faculty or administrators engage with his office on research security issues. He added that the university is moving away from generic training and toward an approach that favors one-on-one interaction with faculty. When meeting one-on-one with faculty, he said, he and his staff develop a written research security technology plan to guide researchers as they conduct research. They also collect faculty feedback about research security issues, including via surveys. Data are reported to the university’s executive vice president and used to determine whether research security efforts are helpful to the research community.

Stalker-Lehoux said that NSF is measuring the number of research security–related inquiries originating inside the agency, as the numbers provide an indication of awareness. The agency is also reviewing how many proposals require risk mitigation.

Stalker-Lehoux said that there is a need for data-sharing among federal agencies, including with DOD. NSPM-33 describes requirements around information-sharing that may be informative.8 Shared information must be

___________________

7 See National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2022. Protecting U.S. Technological Advantage. The National Academies Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/26647.

8 NSPM-33 (see footnote 2) states, “Heads of agencies shall share information about violators (e.g., those who violate disclosure or other policies promulgated pursuant to this memorandum, participate in foreign government-sponsored talent recruitment programs . . . or whose activities clearly demonstrate an intent to threaten research security and integrity) across Federal funding institutions and with Federal law enforcement agencies, the DHS, and State, to the extent that such sharing is consistent with privacy laws and other legal restrictions, and does not interfere with law enforcement or intelligence activities. . . . Heads of agencies should consider providing notice to other Federal funding institutions in cases where significant concerns have arisen but a final determination has not yet been made. Where appropriate and consistent with applicable law and appropriations, funding agencies shall include within grant terms and conditions provisions that allow for such information sharing.”

objective and factual because different agencies may make different decisions about risk mitigation based on the same information. Stalker-Lehoux said that developing data-sharing capacity has been a slow process, but that headway is being made.

Stalker-Lehoux said that agency differences in risk tolerance are a challenge. She challenged the research community to collect data to inform risk tolerance. While there may be great benefits to cooperation, they would be lost without a firm understanding of the risks. “We can benefit from that cooperation,” she said, “even if it is with a researcher from a risky institution.”

Kohler suggested that the NSPM-33 should have been accompanied by funding for universities to collect data. A key question is how much time an investigator spends on research security requirements versus core research. Dao said that it is not clear how much is being spent, as the question has not been studied. He surmised that much of researchers’ time, particularly those receiving mitigation letters, is spent identifying past collaborations. Faculty who publish more frequently are more likely to be targeted for collaboration by foreign adversaries and those targeted by foreign adversaries are more likely to have been engaged in collaboration.

Nichols asked about how to address inconsistencies between agencies on research security policies, such as on risk tolerance. Stalker-Lehoux said that, when NSF was developing its risk framework, the foundation asked DOD whether their framework should be consistent with DOD’s. While the agency was advised to take a nuanced “NSF” approach, she said that it is only through information-sharing that agencies can appreciate different approaches and risk mitigation efforts.

Workshop planning committee member Deanna D. Caputo (MITRE) said that faculty may be hesitant to take research security training or do not want training, suggesting that language around training should emphasize education, awareness, and behavior change. Changing the culture around research security is critical, she said: “We cannot expect good measurement of effectiveness if we do not know how far that culture changed.”

Paté-Cornell suggested that one approach might be to share examples of real cases where U.S. research has been given to the Chinese, what was done with it, and why the acquisition was bad for the United States. Stalker-Lehoux said that, when NSF presented an example to staff of a proposal that had a risk mitigation plan, it generated a lot of conversation.

Positive examples of successful research security measures will also incentivize people to be honest and forthcoming about research security. “Framing matters,” Stalker Lehoux said. Rather than describing issues in a “scary, geopolitical context” where “everyone is going to get in trouble for

collaborating,” she suggested describing examples in a manner where individuals understand that there are always risks. Furthermore, it is important to be thoughtful and keep research transparent, open, and secure.

Workshop planning committee member Amanda Humphrey (Northeastern University and Northeast Regional SECURE Center) asked about data that might be available to help institutions calibrate how many staff are needed to support research security programs. Dao said that, to make decisions, universities can use a triage model that considers the needs of their institution, areas of expertise, whether work touches on critical infrastructure, the types of populations involved, and potential risk of the work.

Workshop planning committee member Dewey Murdick (Georgetown University) suggested that institutions are starting to make decisions about where to apply for funding on the basis of research security considerations. He asked if there are data on this or plans to capture these data. Walker said that, while he does not have data, this is a critical point. Stalker-Lehoux has heard anecdotally that some institutions do not want to address research security restrictions and suggested that this is why NSF and others are trying to further “a risk-tolerant approach to research security.”

Fox observed that session panelists talked about research security and risk in terms of type of research (e.g., fundamental or basic research versus applied research). As some areas of research present more significant risk than others, she asked for comments on how to conduct a risk analysis by research topic. Paté-Cornell suggested that there are not many with expertise in agencies to conduct risk analysis and that training is needed to fill this gap. Stalker-Lehoux noted that, while the 2019 JASON report recommended conducting risk assessments at the project level, she focuses on proposals in sensitive technology areas. For proposals dealing with sensitive technology, she “tries to make the assessment at the project level.”

Audience member Jim Belanich (Institute for Defense Analyses) asked whether there are combined quantitative and qualitative metrics that can be used to evaluate research security initiatives. Stalker-Lehoux suggested that DOD may have these types of metrics and that combining qualitative anecdotal data and quantitative data could be informative. Dao agreed that there is a need for combined qualitative and quantitative metrics. He said that Rice submitted a proposal to NSF to study sophisticated methods from social science, epidemiology, and economics to test whether anecdotal risks that have already been identified by the U.S. government can inform the development of research security metrics.

Audience member David Biggs (U.S. Department of State) asked how to convene all sectors to make decisions about evaluating research security. Dao said that, while the goals of research security are different for professors than they are for administrators or the government, it is important to begin to reach agreement on the goal of research security before developing policies, guidance, and evaluation efforts. Stalker-Lehoux suggested that all parties have the common goal of ensuring that there is no undue foreign interference across the U.S. research ecosystem.

A member of the online audience asked what, if any, assessment of student candidates or new hires is performed to evaluate potential foreign influence risks. Dao suggested that the underpinnings of such assessments come from the 2019 and 2024 JASON reports9 and DOD and NSF models for risk evaluation. Risk assessment often follows what the agencies are looking for (e.g., entities of concern, contracts with foreign talent programs, denied entity collaboration, overseas patents)—assuming that these are accurate, reliable, and valid factors.

McQuade concluded the session by noting that the national security and economic value of leadership in science and technology has not changed. “We are,” he said, “no longer in a landscape where we could afford to be magnanimous because we were ahead of everybody in almost all relevant aspects of science. It is no longer a landscape where we can make simple national security decisions and say, ‘We need to protect that at all costs,’ because in protecting at all costs, we damage economic security,” he said. The fundamental question is, “What level of throttle do we want to put on the free exchange of information and collaboration, and how do we measure the impact?”

___________________

9 JASON. 2019, December. Fundamental Research Security. JSR-19-2I. The MITRE Corporation, https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/files/JSR-19-2IFundamentalResearchSecurity12062019FINAL.pdf; JASON. 2024, March 21. Safeguarding the Research Enterprise. JSR-23-12. The MITRE Corporation, March 21, 2024, https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/files/JSR-23-12-Safeguarding-the-Research-Enterprise-Final.pdf.

This page intentionally left blank.