Defense Software for a Contested Future: Agility, Assurance, and Incentives (2025)

Chapter: 2 Agility

2

Agility

INTRODUCTION

The current climate of world conflict highlights the importance of agility in the weapons and information systems that support modern warfare.1,2 Rapid adaptation of weapons systems such as drones, command control and intelligence systems, and logistics have proven critical to battlefield success. Today such systems rely heavily on software.

In the context of the study, agility refers to

- The ability of software development organizations to deliver functional and assured software systems rapidly in response to users’ evolving requirements and

- The ability of those organizations to modify or update finished software systems in response to new or changed requirements, the discovery of errors, or security vulnerabilities that lead to new or unmitigated threats.

The end user (organization) of the software, rather than the development organization, determines whether the software is sufficiently agile, satisfactory, and fit for purpose.

___________________

1 V. Nabukhotny, 2025, “Ukrainian Innovations Are Redefining the Role of Drones in Modern War,” UkraneAlert (blog), Atlantic Council, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/ukrainian-innovations-are-redefining-the-role-of-drones-in-modern-war.

2 Al Jazeera Staff, 2025, “Israel Retrofitting DJI Commercial Drones to Bomb and Surveil Gaza,” Al Jazeera, May 8, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/5/8/israel-retrofitting-dji-commercial-drones-to-bomb-and-surveil-gaza.

ACHIEVING AGILITY

There are three factors that have been demonstrated by commercial adopters of agile methods to enable a software program to achieve agility:

- Continuous stakeholder engagement: Stakeholders, including end user organizations, should have continuous engagement in system acquisition and software development, including early and ongoing exposure to the emerging software system, and an empowered voice regarding its requirements and acceptability.

- Capability and architecture: The software program must define a decomposition of components (referred to as architecture; see below) that can be acquired, iterated, and designed separately allowing for re-use of common components, diversity of providers, parallel development leveraging common infrastructures, and rapid adaptation to evolving requirements and technologies.

- Continuous integration and assurance: The program must build versions of the entire software system that can be tested (ideally daily or more often) for function, security, and performance and that can be exposed to end users and other stakeholders. This objective is achieved by the use of a continuous integration (CI)/continuous deployment (CD) pipeline that provides seamless support to code development, security testing and scanning, system build, testing, and deployment to operations. The software program must address assurance at both the overall system level and within individual components. Assurance serves as an enabler to continuous integration and agile deployment of system capabilities. Commercial products and online services are routinely exposed to cybersecurity attacks. For defense systems that are infrequently exposed to actual adversaries, testing, training, and exercising must serve as a proxy to identify security vulnerabilities.

OVERVIEW OF THIS CHAPTER

Commercial software and cloud service vendors and information technology organizations have adopted agility as a core component of their development practices. The first three subsections below provide more details about each of the factors—stakeholder engagement, architecture, and continuous integration (and the associated concept of software factories)—and discuss related learnings from the commercial world.

The fourth subsection delves into the issues of agile development in DoD. It summarizes current policies and practices related to user engagement, architecture, and continuous integration and introduces some specific issues related to DoD’s practice of agile development. The final subsection presents findings and recommendations pertaining to agility.

Readers who are familiar with the concepts and operation of agile software development processes, software architectures, CI/CD pipelines, and open-source and “inner-source” software may wish to skip to the subsection on agile software development in DoD.

CONTINUOUS STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT

Software development organizations have sought to meet users’ requirements since the beginning of the computer era, and numerous development models have been tried, some focused on unchanging requirements and others on rapid adaptation to users’ needs. In 2001, a group of software developers met and drafted the “Agile Manifesto,”3 which aims to formalize principles for creating software that will meet users’ needs. The key message of the Agile Manifesto is to value

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools4

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan5

In short, the customers for the software decide whether or not it is valuable, and rapid, direct customer feedback is critical to successful software development.

In the commercial world, the application of the Agile Manifesto takes multiple forms depending on the kind of software being developed and the business model of the developer. For an in-house software development team, the model may be short (a week or two) “sprints” that produce new capabilities that are deployed at once to end users or customers. For commercial vendors of packaged software, new software

___________________

3 Agile Alliance, n.d., “The Agile Manifesto,” https://www.agilealliance.org/agile101/the-agile-manifesto, accessed June 11, 2025.

4 Note that processes and tools (e.g., for configuration management and testing) do play a critical role in successful agile environments, in that they help enable an agile workflow while maintaining acceptable levels of project risk. See the discussion of continuous integration (CI)/continuous deployment pipelines below.

5 An important factor worth noting as well is the guidance to defer design decisions until they actually have to be made; at that point there is often more information available, leading to better decisions.

versions are deployed internally and to customers who sign up to try new versions so that the organization and some customers can “dogfood” new features. Organizations that offer online services may deploy hundreds of feature updates per day, rolling them out first to a sample population of customers by directing a portion of customer traffic to servers running the new software. Instrumentation in the application and cloud platform enables developers to monitor the performance and stability of new features, as well as customer reactions, and provides the capability to revert an update should problems manifest.

In each commercial scenario outlined above, user feedback is monitored so that developers can know whether they are proceeding in the right direction or whether the development needs to make a rapid course correction. Users benefit by being provided with enhanced capabilities sooner, and development teams benefit from increased and timely confidence about whether their efforts are producing valuable results for users.

CAPABILITY AND ARCHITECTURE

Software architecture refers to the high-level design and structure of a software system, focusing on the organization of components and their interactions and emphasizing modularity and well-defined boundaries. In a number of ways, architecture is critical to the successful creation and sustainment of any large-scale software system. For example,

- An architecture allocates specific functions to specific components and thus enables the development team to bound the scope of changes required to add new functions, support new hardware, or correct errors.

- A good architecture enables multiple development teams to contribute to the creation of an overall system without requiring a costly and time-consuming integration phase—the architecture effectively tells each team how their contribution will “plug in” to the finished system.

- A good architecture can enable the reuse of components across systems while minimizing the need for adaptation, rework, or customization.

Software architecture represents the fundamental structure and organization of a software system, serving as a blueprint for both the system itself and the project team. It guides the design and implementation processes, defining the overall system structure, key components, their interactions, and the principles and constraints that shape the system.

Although many customers and developers have encountered collections of boxes and arrows that are often referred to as “marketectures,” a sound software architecture must encompass elements such as

- Modules. Individual modules make up the system—particularly software—but certainly all hardware and firmware as well. The size and complexity for each module will be dependent on the project itself.

- Dependencies. The nature of dependencies, where one module relies on the functionality and behavior of another, must be enumerated.

- Interfaces. The interfaces exposed by a module for use by other modules or external clients must be well defined, strongly typed, and side effects identified.

These elements are essential for ensuring that a system meets its requirements and can evolve over time while remaining robust and efficient. Architectural practices adopted by specific organizations and for specific types of systems may mandate additional elements including common patterns, quality requirements, and documentation standards.

As a concrete example, consider Docker, Kubernetes, and virtual machines (VMs). Modern cloud service development often calls for services to be factored into manageable chunks such as microservices, isolating components from each other. A large service, such as a video service, would have an architecture describing how the functionality is separated into components that work together. The architecture would define the patterns of communication between the components, specifying the interface exposed by each component.

Many of these components would then be placed individually (or combined) into Docker instances. The architecture would inform how and when these components could be combined. Perhaps some components would not perform well in a Docker container and would instead need to run in a VM; ideally this would be identified in the architecture and planned for up front. To roll out the service, the architecture would inform the scheduling and resources needed. This would manifest in Kubernetes scheduling policies.

Rarely does a single, thousand-page architecture document serve the needs of the project or the engineers involved. Reasonable people can and do disagree on the correct level of detail and granularity for a given project. The architecture documents are tightly bound to the culture and patterns of the team—creating an architecture document that no one reads does no good. Much like the architecture documents that define a house,

there are many views required, and many details, and many subsystems; putting them on one page would be chaos.

Successful architectures deliver the benefits listed at the beginning of this chapter by enabling development teams to operate independently without fear that their deliverable will fail or require rework when it is plugged into the larger system. A development team delivers a module that performs a specific function while relying on well-defined interfaces to provide supporting services and exposing interfaces that other modules can rely on. The development team can be as creative and flexible as needed and, as long as its module honors the architected interfaces and is explicit about dependencies, it can be assured of relatively rapid integration into an overall system.

In systems with contributions from multiple independent development organizations, well defined architectures allow teams outside the main development organization to participate and deliver value as well. Conversely, poorly defined architectures (e.g., with incomplete or ambiguous specifications) will scare off outside teams, because the likelihood of success is lowered by the lack of clarity.

Architectures must be compatible with the requirements (e.g., for performance, adaptability, and interconnection) of the systems they are describing. Some architectural decisions are much more difficult to change than others, and it is crucial to understand the implications of one’s decisions. For example, the decision to model data on a relational database rather than a NoSQL database, or to adopt microservices and remote procedure calls rather than a message bus architecture is difficult to change, and an incorrect decision can lock the project into a performance or reliability bottleneck. Conversely, architectural decisions that are hidden behind a service API (i.e., are implementation details) are easier to change if necessary (like adding a caching layer or splitting a service backend into multiple microservices). Similarly, some architectures are more malleable than others. For example, a stateless service backend is easier to shard for scaling purposes than a stateful one.

Teams that define and maintain architectures should consider the full range of likely applications and attempt to predict the implications of the architecture and revise the architecture when new challenges arise. Adhering to a poorly designed architecture, or one that is misapplied, can negate the benefits that an architecture should deliver and lead to poor system performance, reliability, or security. Jennifer Pahlka’s book Recoding America6 describes a scenario in which a contractor’s reading of a standardized government architecture led to the misapplication of an architectural concept referred to as an Enterprise Service Bus. As described, the attempt to build a system that incorporated

___________________

6 J. Pahlka, 2023, Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better, Metropolitan Books.

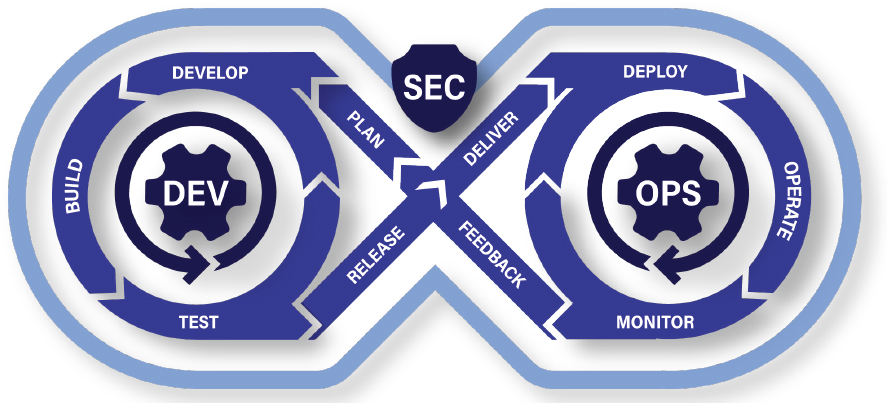

SOURCE: Department of Defense, 2024, DoD Enterprise DevSecOps Fundamentals, Version 2.5, October, https://dodcio.defense.gov/Portals/0/Documents/Library/DoD%20Enterprise%20DevSecOps%20Fundamentals%20v2.5.pdf.

an Enterprise Service Bus had a major negative impact on the development of a new ground processing system for the Global Positioning System.

CONTINUOUS INTEGRATION AND CONTINUOUS DEPLOYMENT

The software development approaches that underlie the agile model differ significantly from traditional waterfall or spiral development models. Instead of operating on a fixed cycle that follows the path develop – unit test – integrate – system test – release, agile development teams make continuous code contributions or updates and build them immediately into the evolving version of the software product or service. This process is referred to as CI/CD. The infrastructure that enables developers to operate under this model is referred to as a “software factory.”

Agile development using a software factory is most effective when it incorporates the DevSecOps approach to development and deployment. The typical description of DevSecOps in this context looks something like Figure 2-1.

The core DevOps model, created around 2008, focuses on moving away from a comprehensive up-front design model and incorporates the actual experience of using the product as part of the development. Thus, a more moderate amount of planning leads to coding, building the product, and deploying the product. While in deployment,

the same engineers who built it operate the product, gaining first-hand knowledge of how to manage it, including whether sufficient information is generated to debug problem situations and keep the product running. This experience feeds back into the planning cycle, and thus a virtuous cycle is created.

However, it soon became apparent that securing the product involves more than just secure coding practices. The most rigorously designed and hardened service is, for example, still broken if it is deployed with the administrator password “Password123.” DevOps evolved to DevSecOps starting in 20107 as both an acknowledgment of and commitment to the pervasive nature of security in software products. Just as original DevOps had a virtuous cycle where the engineers would update their logging capabilities in response to their lived difficulties in diagnosing problems, DevSecOps captures the influence of and need for security in each step of the cycle. Secure development practices, discussed at length in the next chapter, mean that design and planning reflect security needs and features, coding is done in a manner that prevents compromise, building and deployment are done with secure and reliable mechanisms, logs are inviolate, and so forth.

Two key principles underlie this approach to testing and integration: (1) the pipeline automates as much as is possible, and (2) quality work “shifts left” to be as early in the process as possible.8 Automation ensures consistent use of tools and adherence to development standards in the production cycle. However, this focus on automation, and the CI/CD aspects of the process, are still only part of the promise. As with other systemic changes, the full benefit of the agile approach supported by DevSecOps is a cultural change that permeates the organization. As noted by the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, “Agile … represents a true paradigm shift in the way work is planned, executed and structured.”9

The high level of automation inherent in a software factory or DevSecOps pipeline can ensure the capture of tool outputs and test results that are evidence of the quality and security of the software under development. This capture is automatic and a side effect of the pipeline—it requires little or no developer effort beyond what is needed to produce high-quality, secure software. As such, the software factory is especially well adapted to the “assurance case” model of evaluating software security and other properties. The chapter on “Assurance” goes into detail on the assurance case model.

___________________

7 S. Lietz, 2024, “History of DevSecOps,” Devops Institute, https://www.devopsinstitute.com/the-history-of-devsecops.

8 Department of Defense (DoD), 2020, “OSD DevSecOps Best Practice Guide,” https://www.dau.edu/sites/default/files/Migrated/CopDocuments/DevSecOps_Whitepaper_v1.0.pdf.

9 DoD, 2020, “Agile Software Acquisition Guidebook,” https://www.dau.edu/sites/default/files/Migrated/CopDocuments/AgilePilotsGuidebook%20V1.0%2027Feb20.pdf.

Source Code Control

DevSecOps is a methodology for managing the software development process and does not directly address the adjacent question of ongoing source code management. Source control in general refers to the system used to store the source code for a software project, including tooling to manage the change history. There have been many such systems existing as both commercial software (e.g., Perforce) and free software (CVS, Git). While the goals for any given system will reflect priorities or commercial features, the main elements are change management and branching.

Change management allows multiple authors to work within a single source file, ensuring that non-conflicting changes are made smoothly and conflicting changes are identified and raised to the appropriate engineers to be resolved. Part of change management also involves change history, where interested parties can examine the changes made to a file over time, allowing them to link changes in behavior of the software product to changes made in the source code.

Branching is the term of art for allowing an engineer to make a copy of some set of the source code and use that as the basis for further development. This technique allows the source control system to hold all versions of the source files and also enables others to create a view of different versions for their own development. For example, the “main” branch of a project can continue in normal development with regular builds and deployments, while a developer working on a larger feature can create a branch where all the files are the same as the main branch except for the 30 that he or she is working on.

Open Source

The general model of open source, in which source code is made public (open), a wide community of developers can contribute, and the resulting software is free for reuse and modification, has revolutionized software development, with both tremendous improvements and great risk. While the open-source model in general could be traced to the Free Software Foundation,10 it was the advent of Linux into mainstream adoption that sparked the largest growth. The model has evolved to an enabling model, where rather than writing complex functionality from scratch for a project, the engineer or company can select an open-source module to incorporate directly. This allows a team to focus on the new functionality that they are creating rather than writing yet another logging system, or pie-graph renderer, or so on.

___________________

10 See the Free Software Foundation website at https://www.fsf.org, accessed June 11, 2025. See also the philosophical underpinnings contributed by Eric Raymond’s The Cathedral and the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Cathedral_and_the_Bazaar, accessed June 11, 2025.

The open-source model has enabled rapid product development by allowing companies to stitch together freely available11 modules. This shows up from cloud-scale critical components such as Apache web server and Kubernetes containers, down to embedded systems where the decoders for various formats of video streams show up in “smart” televisions. Major software providers such as Google12 and Microsoft13 make some of their internal modules available this way. Smaller companies can provide expertise in specific areas, or use the open-source model to boost their visibility.

The open-source model is not entirely without risk; it turns out that not everything on the Internet is as it seems. A GitHub-hosted site for the widely used react library can look the same as the GitHub-hosted site from “Fred’s Ace Development Shop.” A critical component can be stable but managed by a single unpaid developer.14 Widely used components can have security flaws; once they are discovered and patched, everyone who incorporates that component must update as well, as the Log4j issue reinforced.15 And, of course, there is the risk of malicious software getting in—widely used libraries make for tempting targets, and attacks such as the xz-utils supply-chain attack have already occurred.16

Owner/Maintainer

The general model for an open-source project is a single person or small committee that is in charge of committing changes suggested by a larger population. Many developers in the world can create (or fork17) a branch, then fix bugs or add functionality. However, they will need to have the project committer approve the change, called a pull-request. At that moment, the committer determines what can be merged in, and what standards they must meet.

Inner Source

Inner source is a branch, so to speak, of the open source movement. Firms have discovered that the open source model can be efficient and can yield improvements to their software. However, for any number of reasons, they may have proprietary software

___________________

11 Subject to various forms of licensing.

12 J. Bankoski, P. Wilkins, and Y. Xu, 2011, “Technical Overview of VP8, an Open Source Video Codec for the Web,” In 2011 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo, IEEE, https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en/us/pubs/archive/37073.pdf.

13 Ç. Çalık, “SymCrypt,” Github (repository), https://github.com/microsoft/SymCrypt, accessed June 11, 2025.

14 XKCD, 2017, “XKCD: Dependency,” https://xkcd.com/2347.

15 Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), 2021, “Mitigating Log4Shell and Other Log4jRelated Vulnerabilities,” https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa21-356a.

16 J. Corbet, 2024, “A Backdoor in XZ,” LWN, https://lwn.net/Articles/967180; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024, “CVE-2024-3094 Detail,” NIST National Vulnerability Database, https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2024-3094; D. Goodin, 2024, “What We Know About the xz Utils Backdoor That Almost Infected the World,” ARS Technica, https://arstechnica.com/security/2024/04/what-we-know-about-the-xz-utils-backdoor-that-almost-infected-the-world.

17 A fork is a codebase that is created by duplicating an existing codebase and, generally, is subsequently modified independently of the original.

that they do not want the world to see, or even to allow out of the corporate environs. GitHub may offer sufficient separation from others in some cases but may not allow sufficient separation for some projects.

Inner source is an effort to create the open-source contribution mentality within a smaller space. Teams within an organization can contribute to other teams’ projects, but still subject to the destination team’s committer. When a developer in one team discovers a bug in another team’s component, they can submit a fix. If new functionality is needed, the two teams can negotiate resource allotment and perform the work jointly.18

The inner-source model allows the approved library to accumulate new functionality efficiently. Because of the high-assurance nature of the approved library, the owning team can run any changes through their full battery of tests and analysis before accepting any changes.

AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT IN THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

Continuous Stakeholder Engagement with the Software Pathway

Historically, DoD programs have acquired software using processes similar to those used to acquire aircraft, tanks, or ships: the acquisition program office develops a specification document that lays out the functions that the software is required to perform and any performance attributes that are required (e.g., accuracy or response time) and standards that must be met (e.g., for message formats or user interface properties). The program office also develops a statement of work (SoW) that lays out the tasks that the contractor is required to perform during the development of the software (e.g., producing design documents for government review and running certain tests). The assumption is that the specification and SoW are correct and sacrosanct, and the contractor should be held accountable for meeting them to the letter.

The reality of government software procurement has often differed markedly from the assumptions by “the system.” Requirements were (almost inevitably) imprecisely specified with the result that the contractor’s and government’s understanding differed. Requirements at best reflected the end user’s needs at the time when the system was initially conceived and planned. By the time the system was delivered, the user’s requirements had changed, but the program office could only reflect those changes by changing the specification or SoW and renegotiating the contract—inevitably leading to higher

___________________

18 A variant of inner source referred to as “monorepo” offers increased integration across projects and codebases, enhancing collaboration and software reuse, at the price of diminished isolation and individual control among projects. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monorepo.

costs and longer schedules. All too often, the result was a system that failed to meet user requirements or a system that was late and over budget, or both.

In response to the challenges of software acquisition, over the past 10 years, DoD, like the private sector has initiated software development programs (as heard in committee briefings on Kessel Run, Black Pearl, Platform One) that have demonstrated significant progress on each of the factors that enable agile software development. In particular, each of these programs has incorporated direct user engagement, rapid rollout to users of new software capabilities, and timely user feedback.

DoD has been chartering committees to study the challenges of software acquisition since the 1990s (see Appendix C) but, with the exception of limited programs such as Kessel Run, the challenges and difficulties sketched above continued unabated until recently. The turning point seems to have been a 2018 Defense Science Board (DSB) study that recognized the dynamic nature of software requirements and advocated a more agile process that builds on the successful practices of COTS vendors.19 The recommendations of that 2018 report appear to have been reflected in the creation of the software pathway as the mandated way for DoD to acquire software.

DoD Instruction 5000.87, “Operation of the Software Acquisition Pathway,”20 released in late 2020, is DoD’s version of agile development. The instruction significantly streamlines the process to acquire and deliver software capabilities to end users rapidly and iteratively. The instruction reflects the realities of software development and the lessons learned by industry. It applies to open, proprietary commercial, and DoD custom software applications that run on COTS computer systems or cloud platforms and to software that is embedded in military-unique hardware systems. Furthermore, the instruction specifically identifies the need for development programs to engage continuously with user, design, development, test, and evaluation communities and to establish and maintain software architectures. Designation of the pathway to be utilized from program inception to delivery occurs immediately following requirements validation, largely to ensure consistent acquisition life cycle oversight checkpoints.

The software acquisition pathway addresses each of the three critical factors underpinning agility, listed above, and provides programs with guidance on achieving agile development. Of particular importance is the fact that the instruction emphasizes the need for user engagement and feedback as software development proceeds—a significant change from the traditional model under which requirements were set at the beginning of a program and were expected to remain inviolate. A recent Secretary of Defense

___________________

19 Defense Science Board (DSB), 2018, Design and Acquisition of Software for Defense Systems, February, https://dsb.cto.mil/wp-content/uploads/reports/2010s/DSB_SWA_Report_FINALdelivered2-21-2018.pdf.

20 DoD, 2020, “Operation of the Software Acquisition Pathway,” DoD Instruction 5000.87, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/500087p.pdf.

memorandum21 directs essentially universal adoption of the software pathway for DoD software development programs.

A number of DoD programs have formally adopted the software acquisition pathway22 with the ratio of programs operating within the software acquisition pathway increasing, as compared to Major Defense Acquisition Programs,23 the umbrella acquisition designation under which most weapons systems are developed. A 2024 DSB report24 states that “no weapons system programs have adopted the software pathway” and that today’s milestone-based test and evaluation process inhibits the intended use of the software pathway. Program managers and associated oversight bodies have generally avoided designating sub-components of an acquisition under differing acquisition pathways even though DoD Instruction 5000 permits such an approach. The 2010 National Research Council report Achieving Effective Acquisition of Information Technology in the Department of Defense25 outlines recommended test and evaluation process transformation to continuous operational testing with actual user engagement that should also be applied to mixed acquisition pathway approaches.

Briefings to the committee indicated that the Army’s Ground Combat Systems Program Office has two programs (XM-30 Ground Combat Vehicle and Robotic Combat Vehicle) that have adopted the pathway, and the U.S. Air Force Kessel Run program and the U.S. Navy Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) Command Program Executive Office (PEO) Integrated Weapons Systems (IWS) Forge program have adopted many practices similar to those mandated by DoD Instruction 5000.

As with other practices mandated by the instruction, DoD software organizations are beginning to adopt CI/CD pipelines for software development. The Kessel Run, Forge, and Navy submarine programs have adopted development models in which government experts are responsible for planning, prioritization, and adaptation as development proceeds. Contractors provide technical personnel who work alongside government staff and other contractors, but ultimate authority and accountability rest with the government program. This model of integrating the efforts of expert government and contractor personnel appears to have been successful in the cases described to

___________________

21 DoD, 2025, “Directing Modern Software Acquisition to Maximize Lethality,” Memorandum for Senior Pentagon Leadership, Commanders of Combatant Commands, and Defense Agency and DoD Field Activity Directors, https://media.defense.gov/2025/Mar/07/2003662943/-1/-1/1/directing-modern-software-acquisition-to-maximizelethality.pdf.

22 Defense Acquisition University (DAU), 2025, “SWP Programs,” February 24, https://aaf.dau.edu/aaf/software/swp-programs.

23 DoD, 2024, “Program Acquisition Cost by Weapon System: United States Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Request.” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer, March, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/FY2025_Weapons.pdf.

24 DSB, 2024, “Test and Evaluation. Department of Defense Office of Prepublication and Security Review,” https://dsb.cto.mil/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/DSB_TE-Report_UNCLASS_FINAL_August-2024_Stamped.pdf.

25 National Research Council, 2010, Achieving Effective Acquisition of Information Technology in the Department of Defense, National Academies Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/12823.

the committee. The development model adopted by these programs, and mandated by the software acquisition pathway, mimics the successful practices of COTS vendors who reuse components guided by technical architectures and deliver functioning software to their customers in weeks, days, or even hours.

Defense Acquisition University

The new model for software development introduced by the software acquisition pathway and mandated by the Secretary of Defense memorandum will require the training or retraining of many government and contractor personnel. The Defense Acquisition University (DAU) plays a critical role in training DoD program managers, and some contractor personnel, in managing and executing defense acquisition programs. The Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act of 1990 gives DAU a formal role in professional certification of acquisition and program management personnel.26

DAU’s role includes preparing program managers for their responsibilities under the software acquisition pathway, and DAU was developing or updating its software acquisition training as this report was being written. The list in Box 2-1 gives examples of some of the DAU courses under development.

This report recognizes the importance of training to successful implementation of the software acquisition pathway across DoD, and several recommendations in this chapter and the chapter on incentives (Chapter 4) are targeted at DAU.

Architectures for Department of Defense Systems

Legacy programs have traditionally procured large systems as monolithic, custom developments requiring considerable cross-organizational coordination and approval for requirements and acceptance through processes overseen by such organizations as the Joint Requirements Oversight Council and the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation. The software acquisition pathway requires that programs define and maintain software architectures, and some related developments in DoD suggest the emergence of a more architecture-focused and productive approach.

DoD Architecture Guidance and Standards

The DoD definition of and approach to architecture often differs from that of COTS vendors. As reflected by the DoD Architecture Framework27 (DoDAF), DoD considers architecture to include not only the organization of the software components and interfaces, but also operational, organizational, and project characteristics beyond what commercial

___________________

26 DAU, 2025, “DAWIA Career Field Certifications,” https://www.dau.edu/help-center/faq/dawia-career-fieldcertifications.

27 DoD, 2010, “The DoDAF Architecture Framework Version 2.02,” https://dodcio.defense.gov/library/dod-architecture-framework.

BOX 2-1 Examples of Defense Acquisition University Courses Under Development

- CENG 032 - Introduction to DoD DevSecOps Credential

- CENG 033 - DevSecOps Tool Selection, Pipeline Construction & Management Credential

- CENG 034 - DevSecOps Continuous Development in DoD Credential

- CENG 035 - DevSecOps Continuous Delivery in DoD Credential

- CENG 036 - Modern Software Configuration Management Strategies Credential

vendors typically include. The DoDAF also calls for all-encompassing standards and guidance that may stray far from the needs of program managers and software developers to build a system that is functional, assured, and agile. The Air Force experience with the Enterprise Service Bus cited above is an example of misapplication of a DoD architecture.

It is important for DoD to learn from COTS software vendors’ experiences and to enable development programs to focus successfully on the aspects of architecture that are important to building agile systems. As this report was being completed, the Office of the Secretary of Defense released a guidebook28 for the adoption of a Modular Open Systems Approach (MOSA) for the development of DoD programs and systems. The guidebook focuses on the importance of architectures and of adopting modular architectures and open standards when developing DoD systems. It also provides DoD program managers with guidance on how to incorporate modularity and architectures into program planning and documentation.

The DoDAF is an established resource for DoD development programs. Although its scope goes well beyond the technical aspects of designing and implementing modular systems, architectures from the DoDAF can help programs in developing a standardized approach to software program development. Box 2-2 provides a summary of some of the especially useful components of the DoDAF. Thus, the DoDAF should be considered and applied as a resource that can help to define architectures that will improve software development, reusability, security, and speed of deployment.

Digital Engineering

In addition to addressing the key considerations outlined above—bounding the scope of changes, enabling the participation of multiple development teams, and enabling reuse—an architecture for a major DoD system must also be represented in a format that allows for continuous updates as required for agile development with the software

___________________

28 DoD, 2025, “Implementing a Modular Open Systems Approach in Department of Defense Programs,” https://www.cto.mil/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MOSA-Implementation-Guidebook-27Feb2025-Cleared.pdf.

BOX 2-2 Beneficial Components of Department of Defense Architecture Framework

Department of Defense Architecture Framework models that could be beneficial in the development of software architectures for Department of Defense programs include the following:

- OV-1: High-Level Operational Concept Graphic: A high-level graphical and textual description of the operational concept.

- AV-1: Overview and Summary Information: Describes a project’s vision, goals, objectives, plans, activities, events, conditions, measures, effects (outcomes), and produced objects.

- SV-1: Systems Interface Description: Identifies systems, system items, and their interconnections.

- PV-2: Project Timelines: Provides a timeline perspective on programs or projects, highlighting key milestones and interdependencies.

- StdV-1: Standards Profile: Lists the standards applicable to solution elements.

- StdV-2: Standards Forecast: Describes emerging standards and their potential impact on current solution elements within specified time frames.

SOURCE: Department of Defense, 2010, “The DoDAF Architecture Framework Version 2.02,” https://dodcio.defense.gov/library/dod-architecture-framework.

acquisition pathway. The architectural representation provides the artifacts needed to determine the correctness and completeness of the requirements, design and development, and supports traceability of architectural decomposition required for overall system assurance.

DoD identified digital engineering (DE) methodologies and practices spanning the complete program life cycle in the December 2023 “Digital Engineering Instruction” DoD Instruction 5000.97 (hereafter “DE Instruction”).29 The DE Instruction largely requires the adoption of DE for new programs. Although legacy programs may have extensive paper-based design documentation, implementing DE for program updates and modernization provides avenues for those programs to benefit from the efficiencies of DE.

The DE Instruction requires the use of DE as part of the acquisition process for new programs and its consideration for legacy programs. It highlights the need for digital models as the basis for communicating system architecture information and behaviors.

The NAVSEA PEO Unmanned and Small Combatants (USC) PMS 406, the Unmanned Maritime Systems Program Office, is applying DE methodologies, including model-based systems engineering (MBSE) to expedite design analysis and assessments for increased traceability, continuous updates, and assurance and performance impacts. Reliance on architectures and on MBSE during software design and development is

___________________

29 DoD, 2023, “Digital Engineering,” DoD Instruction 5000.97, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/500097p.PDF.

critical for agility, reuse of architectural definitions, infrastructure and components, rapid integration of technology, and innovation and assurance. It is also critical to the introduction of highly assured (e.g., formally verified as discussed in Chapter 3) components or subsystems in software systems in ways that do not jeopardize agility.

The committee heard from briefers that have applied MBSE in defense acquisition programs that the MBSE techniques can be very effective but also complex and costly to apply. The briefers supported investment in improving the usability and effectiveness of these techniques and the systems that support them.

Successful adoption of the DE Instruction is dependent on trained digital engineers in government and industry including acquisition, program management, and system development and testing teams. The DE Instruction directs that the DAU is responsible for workforce training implementation and testing.

Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment Software Factory

The software acquisition pathway anticipates that systems will complete the security and assurance requirements for deployment as an integrated part of the CI/CD pipeline. CI/CD pipelines incorporate assurance methods, techniques, and tools that help software meet security requirements as part of the development process. The software acquisition pathway also directs programs toward the completion and sustainment of a Continuous Authority to Operate (CAtO) under which security certification of both the development platform and the target deployment environment enables new software releases to be deployed almost immediately and without a requirement for exhaustive certification documentation or extensive security testing.

Assurance Beyond Cybersecurity

In DoD systems, the need for agile, rapidly adapting modes of operation drives a need for similarly agile (and changing) mission technology capabilities. This drive spans battlefield and weapons systems, command and control systems, and intelligence systems, as well as in-line logistics, transport, and supply delivery systems. Generally, these are not only security critical but also time critical, and often safety critical. A lack of assurance in a software acquisition pathway would be a stumbling block for agility, with a high price tag for failures and rework. The automation of testing and other assurance checks in the DoD software factory CI/CD pipelines that have emerged—even in pilots such as Kessel Run, which preceded DoD Instruction 5000.87—has been a significant step forward. Further progress can be expected.

Assured Application Software

DoD Instruction 5000.87 defines an application pathway that is prevalent in administrative and primarily user-facing platforms, such as some command control,

communications, and intelligence (C3I) systems as well as systems for human resources, procurement, facilities management, records management, and planning. These systems require agility and may operate on rapidly changing data. Such systems have the potential to accommodate “plug-in” applications with separable, independent functionality to add capability. Although there can be exceptions, many underlying frameworks for such systems change on a moderate (historically, slow) timescale. Static analysis, discussed in Chapter 3, has been highly useful for commercial systems of this kind.

Assured Embedded Software

Software-centric, mission-critical weapons and command and control systems (increasingly including autonomous systems) have user-facing components but generally are grounded in physical and engineering principles and must provide precise operation under strict time and resource constraints. Such systems can be expected to fall under the embedded pathway defined by DoD Instruction 5000.87, where they would receive the necessary engineering scrutiny. These systems differ significantly from conventional applications in that the coupling and interaction of subsystems may be of both a computational and physical nature, variable, and subject to a wide range of risk, including flaws across the broad diversity of software stacks.30 The user-facing components of embedded systems also must mesh with rigorous system constraints.

Because of requirements concerning safety, lethality, and precision, high levels of assurance are mandatory for embedded software. Currently, the burden of assurance for such systems is largely relegated to testing, which is inherently incomplete. Advances in model-based design, digital twins, and their formally related behavioral models can improve the fidelity and rigor of testing and support formal reasoning about the software that implements new capabilities for interacting with the mission system. Agility in these systems will be dependent not only on the agile implementation of new functionality but also on the agile application of assurance measures. Advances in programming languages (such as Rust—discussed below in Chapter 3) can help eliminate many errors during development by introducing strong and extended type checking capability. But new embedded systems typically entail new algorithmic and architectural strategies particular to the mission, which may demand corresponding means of assurance. These strategies might, for example, include domain-specific decision procedures that may be model-based or algorithmic.

Intelligence systems, having heavy dependence on widely varied and distributed sources are an amalgam: part human-facing data systems and interactive mapping

___________________

30 A classic example is the 1997 failure of the Mars Pathfinder, in which priority inversion caused repeated system resets, with consequent large losses of data. This occurred in spite of extant, published methods that would have prevented the error. See L. Sha, R. Rajkumar, and J.P. Lehoczky, 1990, “Priority Inheritance Protocols: An Approach to Real-Time Synchronization,” IEEE Transactions on Computers 39:1175–1185.

repositories, part highly automated sensor systems and sensor-specific analytics. The ability to ingest new collector data and incorporate it into analytic processes and products driven by a dynamic operating environment drives a need for an architecture that facilitates the rapid and assured introduction of new functional subsystems (referred to in this report as a “composable architecture”) and will lead to more agile systems and benefits to user organizations. This concept is discussed further in Chapter 4. New sensor technologies and their associated analyses for constant refinement of situational awareness are already being mainstreamed, so opportunities for dual use exist, although with different levels of criticality and need for agility (e.g., agricultural use of hyperspectral analysis and both airborne and ground-based robotics for livestock monitoring and crop planting and surveillance, or related needs arising during emergency management and disaster recovery). Downstream, offline analytics have characteristics more akin to the application pathway defined by the software acquisition pathway.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Finding 2-1: The Secretary of Defense memorandum mandating the software acquisition pathway highlights the criticality of enhancing software assurance and agility—DoD cannot afford to fail in this endeavor. As demonstrated by programs such as Kessel Run, DoD is capable of successfully emulating proven industry practices for achieving agility. By combining industry practices with the results of DARPA-sponsored research in assurance, DoD has an opportunity to make radical improvements in the software that is critical to the warfighter.

Finding 2-2: Many of today’s monolithic systems have limited component reuse, restricting insight into system behavior that would be required for analysis and assurance, and have long acquisition cycles with limited ability to re-architect.31

Recommendation 2-1: The Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment should direct that software acquisition programs to the maximum extent feasible, decompose monolithic systems as components to be able to define, implement, verify, and sustain composable architectures that will lead to successful development and increased assurance.

___________________

31 Government Accountability Office, 2025, Weapon Systems Acquisition: DOD Needs Better Planning to Attain Benefits of Modular Open Systems, GAO-25-106931, January 22, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-25-106931.

Finding 2-3: Development programs must have access to sufficient expertise to create or select software architectures that are appropriate to the objectives of the system under development.

Recommendation 2-2: The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and the Defense Acquisition University should collaborate to develop policy, guidance, training, organizational, and technical frameworks in support of agility, architectures, and adoption of the software acquisition pathway.

Finding 2-4: DoD guidance on the MOSA and the standards information included in the DoDAF are useful resources for DoD programs that are aiming for agile development.

Recommendation 2-3: The Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment should direct that development programs consider the Modular Open Systems Approach and Department of Defense Architecture Framework guidance as resources for achieving agility, and should provide feedback to the offices responsible for the guides as to the utility of the guidance and potential improvements.

Finding 2-5: In industry, many projects make their initial start by incorporating other components through open-source repositories such as projects on GitHub. Because of the large quantity of source code available, and the broad spectrum of projects, new software systems can be assembled rapidly, even without rigorous architectural definition. While this reliance on open source may work in some private-sector projects, some source libraries still need to be treated with care (for reasons of intellectual property or confidentiality) and are managed with the same tools but not open for public use or inspection. Furthermore, public open-source repositories may not indicate the degree of quality or assurance associated with the code in the repository, and public opensource projects may prioritize flexibility and functionality over assurance. (See the case of log4j where flexibility was prioritized over assurance, leading to a major cybersecurity incident.32)

Once a library is coded and verified through whatever set of tools is most appropriate, its value should not be limited to one project. Industry’s use of internal opensource repositories has boosted reuse and productivity; similarly, DoD could benefit from

___________________

32 CISA, 2022, “Apache Log4j Vulnerability Guidance,” April 8, https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/news/apache-log4j-vulnerability-guidance.

common repositories—currently, no such at-scale sharing exists, as each program often reinvents code.

Finally, in the software community, reputation counts for much and revolves around an engineer’s submissions to projects. For a shared library to be successful, there needs to be a similar, although not identical, pattern where an engineer is rewarded for improving functionality or fixing bugs.

Recommendation 2-4: The Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment and the Services should initiate the development of common software repositories with required maintenance constructs that can host software components across programs and enable programs to reuse components that they did not develop. Both Department of Defense (DoD) contractors and DoD personnel should be incentivized with appropriate rewards for contributions to the repositories.

Recommendation 2-5: The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Services should provide representative highly assured components that integrate into digital model-based engineering, software pipelines, and test harnesses to support rapid evolution, automated testing, and formal assurance. A successful result would be assurance, architectural, and software components that could be reusable across programs.

Recommendation 2-6: The Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment and the Services should establish policies so that submissions to the common repositories from contractors should be rewarded in a fashion consistent with the overall contract. Equally, submissions from U.S. government personnel should also be rewarded in a meaningful fashion.

Finding 2-6: Wide adoption of the DE Instruction will lead to significant improvements in the agility of DoD software systems. The use and benefits of DE are further discussed in Chapter 4 in the subsection “Contracts and Acquisitions.”

Recommendation 2-7: The Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment should emphasize the need for acquisition officials and program managers to adhere to Department of Defense Instruction 5000.97 and implement the instruction’s methods in requirements definition, design, development, and testing. Program officials should be directed

to leverage digital artifacts as a basis for increased assurance through verification of the correctness and completeness of system decomposition.

Finding 2-7: Wide adoption of the software acquisition pathway will lead to significant improvements in the agility of DoD software systems. Adherence to the software acquisition pathway will require flexibility in budgeting and contracting well beyond traditional DoD acquisition practice. Flexible contracting mechanisms, and in particular the Other Transaction Authority (OTA), can be critical to enabling agility in DoD software programs. The use and benefits of OTA are discussed in the Chapter 4 subsection “Contracts and Acquisitions.”

Recommendation 2-8: The Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (OUSD(A&S)) or the Service Acquisition Executives should require Program Executive Officers and program teams to be trained in and evaluated on the software acquisition pathway’s intent and how to launch pilot projects to gain competence in the software acquision pathway, where appropriate. Additionally, OUSD(A&S) should advocate and encourage program officers to pilot a mixed-pathway acquisition approach for program authority consolidation and alignment, including requirements, development, and test areas.

Finding 2-8: MBSE is extremely promising for supporting both agility and assurance but demands significant investment to develop and maintain models, particularly for rich cyberphysical systems.

Recommendation 2-9: The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Service laboratories should invest further in research that makes model-based systems engineering (MBSE) and testing easier to realize and be more effective. In particular, developing formal models of commonly used instruction set architectures and communication devices would directly support MBSE for software-intensive systems.