Asset Management Practices for Mechanically Stabilized Earth Walls (2025)

Chapter: 3 State of the Practice

CHAPTER 3

State of the Practice

The state of the practice described in this synthesis was determined using a survey administered with an internet-based survey tool and disseminated to lead asset management personnel in the 50 state DOTs, as well as asset management personnel in Puerto Rico and Washington, DC.

The survey was subdivided into five main categories focusing on:

- Retaining wall management practices,

- Practices for retaining wall inventory and assessment,

- Methods of MSE wall maintenance,

- Methods for determining MSE wall condition and prioritizing MSE maintenance/rehabilitation projects, and

- Methods for determining MSE deterioration rates and life-cycle costs.

Each category consisted of several questions, for a total of 33 questions specific to asset management of MSE walls. The state of the practice for each category is described in the following sections. Appendix A contains the distributed survey and Appendix B contains compiled response data. Question numbers presented in the following sections correspond with the numbering in Appendices A and B. Respondents were given an opportunity to upload guidance documents for retaining wall repair and rehabilitation. Ohio DOT shared their standard plans for MSE wall repair. These are included in Appendix C to the Contractor’s Final Report which is not included herein but is available on the National Academies Press website (nap.nationalacademies.org) by searching for “NCHRP Synthesis Report 644: Asset Management Practices for Mechanically Stabilized Earth Walls.”

Survey Responses

Responses were requested from 52 DOTs. Of these, 44 DOTs responded in full or provided partially completed responses (85% response rate, Figure 2). Each respondent was asked if their DOT maintained a retaining wall inventory that included MSE walls. Twenty-two (50%) of the responding DOTs reported that they have a retaining wall inventory. The survey was sent to asset managers within each DOT, with the request that the asset managers incorporate feedback from groups responsible for MSE wall management as necessary. The distribution of survey respondents reflects the diversity of DOT groups responsible for asset management of MSE walls. The responses came from asset management (10 of the 44 respondents, or 23%), bridge/structural (11 of the 44 respondents, or 25%), geotechnical/engineering geology (18 of the 44 respondents, or 41%), maintenance (2 of the 44 respondents, or 5%), materials (2 of the 44 respondents, or 5%), and the state retaining wall engineer (1 of the 44 respondents, or 2%). Regardless of which discipline group within the DOT, respondents were primarily engineers in supervisory or managerial roles.

Overview of MSE Retaining Wall Management

The survey sent to each state DOT asked the DOT to estimate the number of MSE walls their DOT was responsible for. The median number of MSE walls that responding DOTs were responsible for (using the definition at the beginning of the survey) was approximately 375. Of the 31 respondents to this question, 14 (approximately 44%) said their number was from an experience-based estimate, 11 (34%) described it as an estimate from a partial inventory, and 7 (22%) described it as a count based on a thorough inventory. When asked to describe their DOT’s current retaining wall inventory (Figure 3), 5 of 39 respondents (12%) reported their DOT had a complete inventory, 17 (42%) reported some form of partial inventory, and 19 (46%) reported having no retaining wall inventory.

Drilling down into the retaining wall inventories maintained by respondents, inventories with walls developed by type alone (e.g., cantilever, MSE, soldier pile) are the most common (12 respondents or 39%). Inventories with MSE walls subdivided by facing type are maintained by 9 respondents (29%), and inventories that include reinforcement type are the least common (3 respondents or 10%). Two DOT respondents noted that their DOTs allow only select types of MSE walls for traffic-bearing walls, making information on facing and reinforcement type readily available, even if it is not officially tracked in a DOT inventory. When asked about the age of their existing retaining wall inventories, 12 out of 15 respondent DOTs (80%) whose DOTs have inventories reported that their inventory databases were less than 10 years old (Figure 4).

When asked what proportion of DOT-owned MSE walls were designed using standards and codes that have since been superseded (e.g., ASD), 24 of 35 respondents (67%) reported that their DOT does not track this information. Of the 12 respondents who provided an estimate, 4 (11%) reported that less than 20% of their DOT’s MSE walls were designed using superseded standards and codes, 2 (6%) estimated it to be 20% to 40%, 4 (11%) estimated 40% to 60%, and 2 (6%) estimated the proportion at over 80% of their MSE walls having been designed using older standards.

Retaining Wall Inventory Practices

Because MSE walls can support various highway needs, from bridge abutments, to embankments, to cut slope support, the survey attempted to collect data on which groups within a DOT are typically responsible for inventorying and assessing MSE walls. Based on the survey responses, within a DOT, bridge and geotechnical groups (followed by maintenance and operations groups) are most likely to be responsible for retaining wall inventory and inspection. When asked who is responsible for inventory data collection, 9 respondents (26%) said the work was completed by DOT staff, 2 (6%) said they hired consultants, and 9 (26%) said they used both, depending on inspection needs and available budget.

Responding DOTs reported using various methods to manage data in their retaining wall inventories, including paper or electronic files in a central location, an in-house database or geodatabase, or a hosted cloud service (Figure 5). No single data management system was used by most respondents. Three DOTs commented for this question that their DOT used a combination of the response options to manage MSE asset data. When asked if their DOT kept records of as-built conditions specifically for use in their asset management program, 18 respondents (53%) reported that they did.

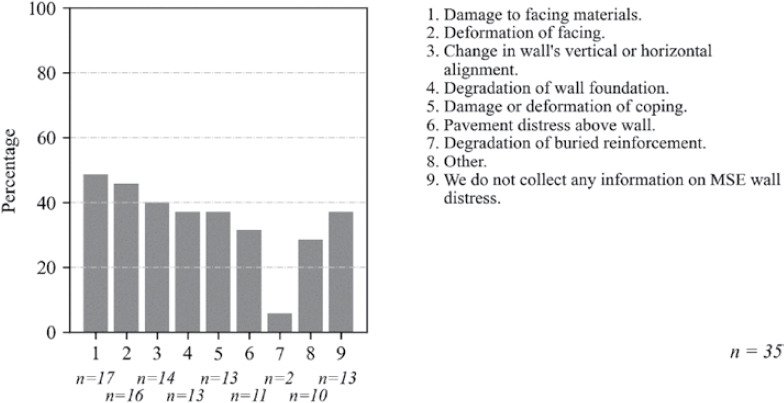

DOTs with retaining wall inventories were asked to select the types of MSE wall distress on which they collect data (Figure 6). Among DOTs that collected such data, damage to facing materials, deformation of facing, and changes in wall alignment were the most common types of distress about which they collected data.

Survey respondents were also asked to provide information on the methods and technologies used to evaluate MSE wall condition and performance (Figure 7). In-person visual inspection was the most common method used, either ad hoc during performance of other duties, in response to a specific request for a post-damage inspection, or repeated visual inspections. When asked if their DOT had identified any non-destructive testing (NDT) methods for degradation of buried elements, 31 respondents (91%) replied that they had not. The 3 respondents (9%) who answered in the affirmative explained that their DOT exhumed buried coupons or geogrid samples to monitor reinforcement degradation.

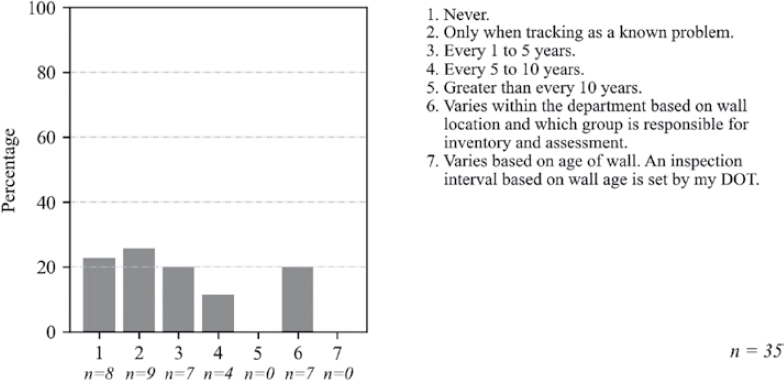

Survey respondents were also asked to provide information on how frequently MSE walls managed by their DOT are inspected following construction (Figure 8). Of the respondents, 8 (23%) reported that retaining walls are not typically reinspected, and 9 (26%) reported that

DOT walls are only reinspected when tracking a known problem. Among respondents reporting a regular reinspection cycle, none reported an inspection interval greater than 10 years.

Methods for Maintenance and Rehabilitation

The survey also attempted to collect data on proactive measures used by DOTs to repair or rehabilitate distressed MSE walls. The measures were separated between work performed inside the original wall footprint and work performed outside it (Table 2). Respondents were also asked to estimate which repair methods had been most cost-effective for their DOTs.

Of responding DOTs 17 (55%) did not perform proactive repair or rehabilitation measures outside the MSE wall footprint while 13 (45%) did not perform proactive repair or rehabilitation measures inside the MSE wall footprint. Among those agencies that had completed proactive repairs outside the wall footprint, repairing erosion damage or improving drainage to direct water away from the wall were the most common measures used (Figure 9). When asked to evaluate how cost-effective these measures had been, 14 of 24 respondents (56%) described drainage improvements directing water away from the wall as the most cost-effective proactive mitigation measure (Figure 10).

Table 2. List of proactive rehabilitation methods and typical location relative to the original MSE wall footprint (provided for Questions 20 through 23).

| Type | Measure |

|---|---|

| Outside of the original MSE wall footprint | Drainage improvements to direct water away from the wall. |

| Erosion/scour repair below the wall. | |

| Removing fill placed above the wall following construction. | |

| Removing material deposited above the wall by landslide or erosion. | |

| Repairing erosion damage above the wall. | |

| Other. | |

| Our DOT does not perform proactive measures. | |

| Inside of the original MSE wall footprint | Clearing drainage channels within the wall. |

| Filling voids behind wall facing. | |

| Installation of additional drainage outlets into the wall. | |

| Installation of structural reinforcement (e.g., soil nails, soldier piles). | |

| Removal of trees or large woody debris from wall face or top of wall. | |

| Repair of damaged/corroded/spalled concrete. | |

| Replacement of missing or damaged facing elements. | |

| Restoration of joint seals around displaced panels. | |

| Revegetation of wall face for wrapped facing. | |

| Treatment to prevent loss of backfill or damage to facing elements (e.g., shotcrete, grouting). |

Among those agencies that had completed proactive repairs inside the wall footprint, restoration of joint seals, filling voids behind wall facing, and repair of damaged concrete were the most common measures reported (Figure 11). When asked to evaluate how cost-effective these measures had been, 6 respondents (23%) described removal of vegetation as the most cost-effective measure employed inside the wall footprint, 5 (22%) reported that repair of damaged concrete elements was most cost-effective for their DOTs, and 3 (11%) responded that restoration of joint seals around displaced panels was the most effective for their DOT (Figure 12). The variability in which mitigation methods are most cost-effective inside the wall footprint may reflect the variety of environments in which MSE walls are constructed.

When planning for MSE wall maintenance or rehabilitation, 3 respondents (9%) reported that their DOT has a programmatic budget set aside for wall maintenance or rehabilitation. When asked if their DOT had a program or guidance for the replacement or rehabilitation of older MSE walls to align them with modern design standards, 34 respondents (97%) stated that no such guidance existed in their DOT. The standard guidance for MSE wall repair and rehabilitation shared by Ohio DOT is provided in Appendix C of the Contractor’s Final Report. This appendix is not included herein but is available on the National Academies Press website (nap.nationalacademies.org) by searching for “NCHRP Synthesis Report 644: Asset Management Practices for Mechanically

Stabilized Earth Walls.” No programs or guidance to replace MSE walls at the end of their design life were identified in this survey.

Incorporation of Condition and Risk into Project Prioritization

DOTs with retaining wall asset management programs were asked to provide more information on how their DOTs defined malfunction and failure of MSE walls, determined wall condition and risk of failure, and how such information was incorporated into project prioritization. Ten respondents (23%) completed this portion of the survey.

When defining malfunction of MSE wall assets, deformation of facing, damage to facing materials, and loss of backfill were the most common performance indicators used by DOTs (Figure 13). Survey respondents used changes in wall alignment to define MSE malfunction as

well, but the absence of this indicator from the top three may reflect the tolerance of MSE walls to post-construction deformation.

In addition to gathering information on how DOTs define MSE wall malfunction, respondents were asked how their DOTs defined service failure (Figure 14). An impact on traffic was the most common metric used to define failure by 9 out of 10 respondents (90%). The respondents who selected “Other” clarified that their DOTs do not have a formal definition of service failure, but that all the metrics listed would require a DOT response.

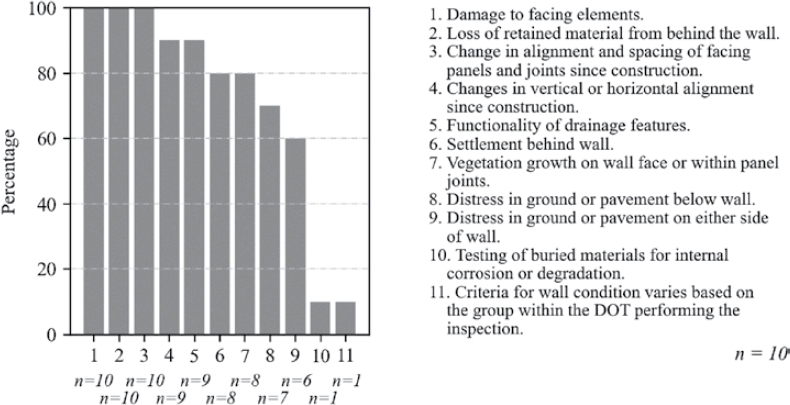

The survey gathered information on how DOTs determine wall condition (Figure 15). All responding DOTs use damage to facing elements, loss of backfill, and change in alignment to describe wall condition. The only inspection item used by less than 6 of 10 (60%) of respondents was testing of buried materials for internal corrosion or degradation (10%, or 1). Criteria for determining wall condition also varied between DOT inspection groups for Louisiana DOT.

In an asset management program, the condition of individual inspection items is compiled into an overall asset condition descriptor. When asked what descriptor was used to describe wall condition, seven DOTs (70%) reported using condition score or category (e.g., 0 to 100, or Good/-

Fair/Poor), while Louisiana DOTD uses qualitative risk, Maine DOT uses qualitative hazard, and Oregon DOT uses a numerical score like the Rockfall Hazard Rating System (RHRS) scoring.

When comparing MSE walls to prioritize spending, three respondents (30%) rank walls using overall condition, one DOT uses likelihood of failure, and three (30%) do not have a formal method for prioritizing wall repairs. The three respondents who selected “Other” use a combination of condition and consequence to prioritize walls.

Decision support tools in asset management programs help the DOT allocate limited funds and improve transparency around project selection. Informal decision support tools are typically used, based on the survey responses. However, four respondents (40%) are formalizing previously informal guidelines. Within these informal tools, three respondents (30%) use a risk-based selection process, two (20%) have a target wall condition for their inventory, two (20%) use a combination of roadway functional classification and target wall condition, and one DOT uses the estimated impact of failure.

Determination of Deterioration and Life-Cycle Costs

In a mature asset management program, costs associated with building, maintaining, and rehabilitating an asset are all tracked by the DOT. Using such data, agencies can develop programmatic deterioration rates and life-cycle costs for a given asset type. These rates and costs are used to forecast the effect of current budget expenditures and to estimate future budget needs. Long-term performance data can also be used to help improve asset design and future performance.

Of the 10 DOTs that answered Questions 25 through 34 about their retaining wall asset management programs, this survey found that MSE wall construction costs and inspection costs are the most common ownership costs tracked (6 out of 10 DOTs). No respondent tracked rehabilitation costs specifically by type of wall repaired (Figure 16). Half (5 out of 10) incorporate long-term deterioration into MSE wall design by applying experience gained from previous failures and from long-term deterioration of existing assets (Figure 17).

Minnesota DOT reported they have developed a life-cycle cost for a generic retaining wall asset. Other respondents (9 out of 10) reported they have not collected sufficient data for a

retaining wall life-cycle cost analysis. No life-cycle costs specific to MSE wall assets were identified by survey respondents.

Key Findings from the Survey Questionnaire

The 44 DOTs that responded to the survey, either in full or in part, provided a valuable overview of the current state of the practice in asset management of MSE retaining walls. Half of survey respondents state that their department has a retaining wall inventory. The survey responses reflect a range of methods being used to maintain these assets and manage the associated data. The variation among respondents reflects the absence of a national mandate to include retaining walls in transportation asset management programs.

Key findings from the state of the practice survey are summarized in Table 3. The table sections reflect the divisions within the state of the practice survey. Responses to specific questions are not discussed in this table. Because not all responding DOTs answered all questions, specific percentages are not included in the table.

Table 3. Summary of key findings from responses to the State of the Practice Questionnaire.

| Survey Section | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Retaining Wall Management Practices |

|

| Inventory and Assessment Practices |

|

| Maintenance and Rehabilitation Methods |

|

| Determination of Wall Condition and Project Prioritization |

|

| Methods for Determining Deterioration Rates and Life-Cycle Costs |

|