Selecting, Procuring, and Implementing Airport Capital Project Delivery Methods (2024)

Chapter: 5 Executing Airport Capital Projects

CHAPTER 5

Executing Airport Capital Projects

5.1 Introduction

Airport capital projects can be complex, potentially involving many stakeholders, multiple funding sources, highly regulated environments, legacy facilities, and work areas that may be subject to operational and security constraints. Using a project delivery method (PDM) that is new or unfamiliar to the airport can create an additional layer of complexity.

To assist project sponsors with managing such challenges and the associated project risks, this chapter describes various tools and strategies that airports have applied to drive improved project performance, particularly when more-collaborative forms of project delivery, such as construction manager at risk (CMAR) and progressive design–build (PDB), are being used. Although some of the strategies discussed here are specific to helping achieve the benefits of a particular PDM, most represent universal good practice, in that they can be effective regardless of the PDM used to deliver the project. Any nuances related to the applicability of a tool or strategy to a particular PDM are clearly identified.

5.2 Organizational Capabilities and Culture

Effective implementation of alternative project delivery systems will likely require some transition on the part of internal airport staff accustomed to a prescriptive mindset (as in, “this is the way we have always done it and will continue to do it”). This is particularly true for organizations that have deeply embedded cultures founded on design–bid–build (DBB) delivery and hard-dollar procurement methods. Such organizations will need to adapt to a more outcome-based approach that requires increased flexibility, enhanced collaboration with external team members and stakeholders, and the ability to assume different roles and responsibilities.

It is important to recognize that internal staff will likely have benefited in the past (e.g., through promotions, pay raises) from exhibiting certain skills and behavior designed to support traditional sealed-bid DBB procurements and that such skills and behavior may not necessarily be directly compatible with the implementation of alternative PDMs.

For example, before embracing the use of fixed-price design–build (DB), several airports reported that in-house staff had to grow accustomed to relinquishing some control over the final design and construction phasing. In addition, staff had to gain experience with developing scopes of work and solicitation documents in terms of minimum requirements and expectations—a task that can often be more challenging than simply developing 100% complete designs and specifications. For the more collaborative delivery methods of CMAR and PDB, staff may need to become more open to working as part of a team that resolves issue jointly instead of fighting battles over what is in versus out of the contract.

Fully integrating a new delivery option into a capital construction program, therefore, often entails fostering a new cultural and organizational context that establishes distinct roles, responsibilities, and standards. It also involves the recognition that, for alternative PDMs to work well, there must be a mutual level of trust and respect between the owner and its industry partners.

Table 5-1. Owner’s changing role under different PDMs.

| Role | DBB | DB (fixed price) | CMAR and PDB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design and scope management | Directive: Airport develops detailed designs (or oversees consultant design) and then inspects the constructed work to ensure compliance with that design. | Advisory: Airport reviews the final design developed by the DB team for compliance with airport-provided scope and performance criteria. (If, instead of simply reviewing for compliance, the airport issues directive design comments as part of its reviews, the result may be change orders and cost overruns.) | Collaborative: Owner works with the design and construction teams to jointly discuss design options and resolve issues, often using building information modeling (BIM) and lean project delivery practices as a platform for collaborative planning and problem-solving. |

| Decision-making | As design and construction services are separated, communication and decisions flow through airport staff. | As design and construction services are integrated under one contract, communication and decisions flow directly between the DB design and construction partners, with airport concurrence sought as needed. | Decisions are made as part of a collaborative team effort that involves representatives from the airport, designer, and contractor, often using a Big Room approach. |

| Change management | Airport staff maintain a largely prescriptive, skeptical, and possibly confrontational mindset accustomed to aggressive negotiation of change orders and claims and fighting battles over what is in versus out of the contract. | Airport staff adopt a more hands-off approach, focused on reviewing the work for compliance with contract documents and holding the DB team responsible for design errors and omissions. However, if changes occur, the lack of cost transparency may make the owner’s subsequent negotiation of a fair and reasonable change order price challenging. | The owner must commit the resources necessary to support a collaborative project execution process and joint resolution of project issues. If changes occur, the open-book nature of the project should assist with the negotiation of the change order price. |

Table 5-1 compares some of the key differences in the roles and responsibilities of the owner under DBB, DB (fixed price), and the more collaborative forms of project delivery such as CMAR and PDB. The specific experience and lessons learned of Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL) related to its rollout of new PDMs are described in Box 5-1.

Organizations that successfully made the transition to include alternative PDMs in their project delivery toolkits reported adopting some or all of the following strategies:

-

Assessment of staff capabilities and training. To successfully implement alternative PDMs, it is important to first evaluate the capability and experience of internal staff, including their willingness to embrace new PDMs and develop softer skills related to collaboration and team building.

- Training may be needed to teach new skills or to apply existing skills in a different manner or to a different end. For example, negotiating skills may be refashioned into joint problem-solving skills.

- Training, both on the job and in the classroom, can serve as a key programmatic tool to transfer knowledge, lessons learned, and skills to designated airport staff assigned to deliver projects with the new PDM.

- One airport also noted the value of conducting an analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) with participation from internal staff. A SWOT analysis highlights existing strengths that could be built upon to successfully deliver a project with a new PDM and to identify areas that would benefit from further training. One airport conducted a

Box 5-1. Rolling Out New Delivery Methods in an Organization: The Experience of Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport

ATL has used a range of PDMs to deliver its capital projects, including CMAR and DB. Lessons learned related to ATL’s rollout of new PDMs included the following:

- Consultant resources. The airport has always relied heavily on consultant resources, so when new delivery and procurement methods were first used, specialty expertise was sought as needed.

- Organizational change management. Staff training must be addressed from the top to the bottom. All parties must understand the need for the alternative PDM and what the airport gains through its implementation. An expert in change management can help facilitate the initial needs assessment and rollout strategy to help gain organizational acceptance of new delivery and procurement methods. If the need for the change is not readily apparent, it can take several months to lay the groundwork for change and bring people along. Ideally, changes should be phased in or first piloted with smaller projects if possible.

- Industry. An organization’s industry partners can present a large obstacle to implementing new PDMs. Since the City of Atlanta has a robust minority and local enterprise participation program, each project must include subcontractor outreach. ATL performs this early with each project to bring parties together and includes outreach requirements in each project. All parties need to understand that the new PDM must either maintain or increase access to opportunities for business enterprises.

- series of workshops on value stream mapping to similarly engage staff to identify any perceived gaps in processes and resources. In both cases, the perceived value of the exercises was to engage staff in open, no-blame conversations about how to build a high-performing project delivery team tailored to a specific PDM.

-

Senior leader commitment. Fostering a culture in which new PDMs will be embraced requires leadership to

- Establish and effectively communicate the specific rationale as to why a new PDM represents a necessary addition to the airport’s project delivery toolbox;

- Recognize the need for key personnel to be educated in the leading practices related to the PDM;

- Align functional support areas and other project partners (including, but not limited to, finance, procurement, project controls, and legal) to ensure the organizational structure supports the effective planning, design, procurement, execution, and closeout of projects;

- Empower project managers with appropriate decision-making authority; and

- Champion the benefits of the PDM to both internal staff and other stakeholders.

- Internal champions. As indicated by multiple airports, effectively implementing new forms of project delivery does not necessarily require all personnel to immediately embrace a new PDM. Initially, only one or two internal champions are typically needed to assist senior leaders with advancing a new method and moving beyond traditional silos that could stifle the collaboration needed for effective and efficient project delivery. Continued support from these champions can then help achieve further buy-in from staff and reinforce any changes in traditional

Several airports reported that PDMs such as DB and CMAR did not emerge as fully viable alternatives to DBB overnight, with both internal DOT staff and industry exhibiting some reluctance to supporting their use. Over time, as the programs matured, such resistance generally declined, indicating a somewhat steep though not insurmountable learning curve.

- roles and responsibilities and standard operating procedures needed to accommodate the new PDMs.

- Use of external consultants. Engaging consultants experienced in alternative delivery can enable airports to execute projects in a new way without a long-term investment in the training and development of internal staff. If a one-off project is large or unique for the airport, this strategy can be an efficient and effective approach to help deliver the project while allowing for some knowledge transfer from consultants to internal staff.

- Development of programmatic documents. The development and maintenance of procedural guidance and standard contract templates, as described in Section 5.3, can help impart the necessary knowledge, lessons learned, and skills to internal staff assigned to project oversight responsibilities.

-

Industry outreach. Like their airport counterparts, industry can also require some time and experience with alternative PDMs before embracing their use. Airports reported that some of the more common issues cited by industry regarding alternative forms of delivery and procurement included

- The perceived subjectivity of evaluations and the selection process;

- The cost of preparing technical proposals and inadequacy of stipends for short-listed firms; and

- The tendency of owners to use alterative PDMs on large, complex projects that limit the ability of smaller contractors to participate.

As potential strategies to help overcome these industry perceptions, airports pointed to the need for:

- Consistent and ongoing outreach workshops to foster a collaborative working relationship with industry partners and to establish support for an alternative delivery program,

- A healthy mix of advertised projects (both size and type), and

- Thorough and informative debriefing that helps educate unsuccessful teams on how to prepare stronger proposals in response to future opportunities.

In addition, if procurement laws require the involvement of local business, a market analysis or exploratory outreach efforts to determine local resources and skills may be necessary prior to selecting the PDM for a project.

- Being ready. History has shown that having projects ready to go, or shovel-ready, creates an enhanced application for grants and programs. Owners can establish a list of potential projects that are possible candidates for alternative PDMs, such as DB, that would not necessarily demand detailed designs to advance to the procurement phase. This is becoming more important as revenues become available from legislation and discretionary grant opportunities. For example, revenues from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 and the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA) of 2021 may provide airports with money that could be used in part for improvements to offset a time of distress.

5.3 Programmatic Documents

5.3.1 Contract Forms

To promote programmatic consistency, many owners have developed (often with consultant or legal assistance) standard contract templates and model forms (e.g., request for qualifications, request for proposals; general conditions; and technical requirements) to facilitate the procurement and delivery of alternative PDMs. These templates and forms typically contain boilerplate language as well as instructions for tailoring requirements to project-specific conditions. Use of such templates can help reduce the effort needed to develop and review solicitation and contract documents for specific projects while also ensuring that roles and responsibilities related to design, quality, third-party coordination, and similar requirements that may change under different delivery

methods are clearly and adequately defined. For example, under all variants of DB, design and construction are integrated. Communication and decisions flow directly between design and construction teams, with owner concurrence at key decision points. Standard contract forms for DB should clearly define the areas where DB changes the traditional roles and responsibilities of the parties for coordination, design, changes, payment, legal requirements, and other key responsibilities. The contract should clearly specify the owner’s role in reviewing and acting upon design and other required submittals, the owner’s role in managing construction quality, and the processes by which the DB team is to report to and communicate with the owner.

Airports with extensive experience delivering projects with CMAR stressed the importance of clearly defining the tasks and deliverables required of the construction management firm as part of its preconstruction services. To provide more definition around the role of the construction manager (CM) during the preconstruction phase, the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) over time developed a detailed preconstruction task and deliverable list that has now been incorporated into its preconstruction services agreement (see Appendix C). An example scope of services from a recent PDB at Nashville International Airport is provided in Appendix D.

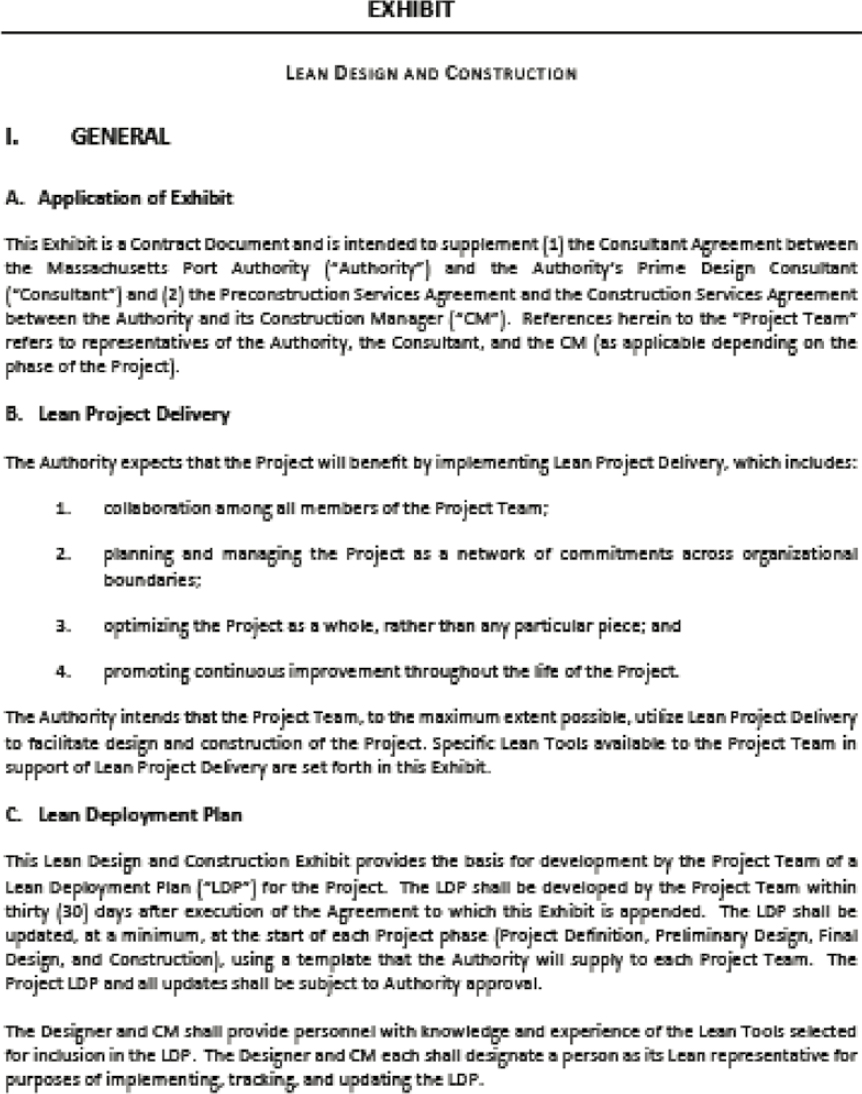

The contract documents should also promote and support, as appropriate, any collaborative aspects inherent to the use of a particular PDM. For example, Massport recently developed, as exhibits to its contract documents, provisions related to the use of building information modeling (BIM) and lean design and construction techniques.

5.3.2 Guidance Documents

Some airports have also established standard policies and guidance documents to further transfer the necessary knowledge, lessons learned, and skills to internal staff assigned with managing and overseeing projects. Massport is a strong proponent of providing its project delivery teams with guidance and templates to help promote consistency in project execution and contract administration. Examples of these guides are identified in Box 5-2.

Box 5-2. Example Guidance Documents

To promote consistency across its project delivery teams, Massport has developed and published several guides and operating procedures, which it maintains on its website at https://www.massport.com/massport/business/capital-improvements/important-documents/.

BIM Guidelines for Vertical and Horizontal Construction

This document provides BIM managers and other project participants with the technical specifications and data requirements for development of BIM models for Massport. In conjunction with the guidelines, Massport developed a BIM template file and a BIM execution plan template to standardize and partially automate the BIM planning activity.

Guide for Validating and Checking BIM Submittals

This document sets forth a quality control protocol designed to be performed at required submittal milestones (e.g., 60% design or model turnover) to ensure that the close-out BIM deliverable is consistent with Massport’s BIM standard,

which in turn will help ensure that Massport’s operations, facilities management, and future construction projects are relying on accurate and high-quality BIM.

Laser Scanning Standard Guidelines and Operating Procedure

This document provides guidance on Massport’s expectations regarding the scoping and implementation of three-dimensional surveys of existing conditions and associated record capture, with a focus on terrestrial laser scanning technologies.

Last Planner® System Minimum Standards Guide

This guide sets forth the minimum standards required by Massport for application of the Lean Construction Institute’s Last Planner® System on Massport projects.

Schedule Toolkit

Massport’s toolkit is intended to support the design and construction management teams in meeting the requirements of the contractual schedule specification. The toolkit includes Massport’s Schedule Cost Loading Guidelines, a Primavera schedule XML file, and Primavera schedule layout PLF files.

Estimating Guidelines

This document is to be used by managers, estimators, planners, programmers, and others involved in determining project cost estimates for Massport capital projects.

5.4 Supporting Collaboration and Team Integration

Several of the airports interviewed that have found success with alternative forms of project delivery stressed the importance of developing relationships between the owner, designer, and contractor project representatives that are built upon trust, transparency, and the lowering of barriers to support team integration and collaborative problem-solving. This finding is consistent with an empirical study commissioned by the Charles Pankow Foundation and the Construction Industry Institute, and conducted by the University of Colorado, which examined over 200 capital facility projects in the public and private sectors and attempted to assess what differentiated successful projects from those that were less successful. The results of the study are available in Maximizing Success in Integrated Projects: An Owner’s Guide (Leicht et al. 2016). The study traced successful outcomes in part to the development of collaborative project teams; the early involvement not only of the primary builder, but also of key trade or specialty contractors; and the selection of project participants through a QBS process.

The early involvement of key industry players and fostering of collaborative teams were among the key measures cited by airport owners as helping them move toward an integrated project delivery (IPD) model even when using two-party CMAR or DB agreements (as opposed to formal multiparty IPD contracts).

The following implementation techniques and tools are used by airports to support integration and collaboration:

- Promoting team-building events (e.g., kickoff meetings, effective onboarding of new team members),

- Engaging specialty contractors early as design–assist partners,

- Using collaborative partnering techniques,

- Engaging stakeholders early and often,

- Using BIM as a platform for collaboration throughout the project’s design and construction phases, and

- Using lean design and construction tools to support collaborative planning and problem-solving.

5.4.1 Team Kickoff Meeting

An effective tool for any PDM, a kickoff meeting or workshop provides the opportunity to promote early team alignment around project goals and processes and the development of effective lines of communication and working relationships.

Design Phase Kickoff

Depending on the delivery method used, multiple kickoff meetings may be conducted over the course of the project, coinciding with the onboarding of different members of the delivery team. For example, with CMAR, the initial kickoff may focus on the design phase only, with participation limited to members of the airport project management team, the design consultant, and, depending upon the nature and scope of the project, additional airport representatives and internal subject matter experts (representing, for example, departments such as safety, compliance, environmental management, utilities, survey, sustainability, resiliency, facilities, fire and rescue, and parking).

Design phase kickoffs are typically used to establish a common understanding of the airport’s preliminary goals for the project, including design expectations, overall schedule and budget parameters, and deliverable requirements. Following are typical agenda topics:

- Basic project overview (e.g., scope, goals, budget and schedule requirements, facility and operational constraints);

- Basic contract requirements, including any airport-specific standard operating procedures, policies, and administrative procedures, including (as applicable)

- Forms and processes for preparing and submitting invoices, design inquiries, and other project communication;

- Site access, badging requirements, working hours, and other building rules and regulations;

- Management of sensitive security information; and

- Access to any internal airport electronic project management information systems that will be used to manage the project;

- Submission requirements (e.g., design deliverables, cost estimates, schedule, BIM execution plan);

- Design review process;

- Handover to the design team of any airport-provided information on existing conditions (e.g., reports, data) pertinent to the project;

- Requirements for coordination with airport stakeholder groups (e.g., utilities, public affairs, asset management and commissioning); and

- Roles and responsibilities of project team members specific to the PDM being used. For example, if CMAR is being used, the predesign meeting should be used to convey the airport’s expectation that the design team will actively collaborate with the construction management firm (once such firm is brought on board) to facilitate constructability reviews and value engineering (VE); reach consensus on a design packaging plan; determine the appropriate level of design detail needed to release design packages for construction; and seek and incorporate continuous input from the construction manager (CM) on the implications for cost and schedule of different design alternatives.

Preconstruction Phase Kickoff

Once the project team expands to include a CM or contractor, a kickoff meeting is beneficial to help bring the new team members onboard, confirm the procedures and protocols to be followed during the preconstruction and construction phases, and establish a common understanding of

project goals, scope, schedule/phasing, design status, preconstruction deliverables, and construction phase requirements. Following are typical agenda topics:

- Project overview (e.g., scope, goals, budget, and schedule requirements; facility/operational constraints);

- Status of the design, including early packages;

- Basic contract requirements, including any airport-specific standard operating procedures, policies, and administrative procedures, including (as applicable)

- Reporting requirements;

- Requirements for project controls;

- Site office/mobilization requirements;

- Coordination with facilities/operations and other contractors;

- Work restrictions/constraints;

- Permitting, including building, safety, and environmental permitting;

- Safety management;

- Environmental compliance;

- Site access, badging requirements, working hours, and other building rules and regulations;

- Labor rate guidelines;

- Prevailing wage requirements;

- Minority, women, and disadvantaged business enterprise (DBE) goals;

- Protocol for payment requisitions, communication, and other correspondence;

- Management of sensitive security information; and

- As-built submissions;

- Design packages/project phasing plan, including early packages and long lead items;

- Bid package strategy;

- Scope and schedule of preconstruction services and deliverables, such as

- Cost estimate/reconciliation;

- Schedule, including construction baseline schedule/phasing plan;

- Constructability input; and

- Plan for bid packages;

- Collaboration techniques, such as

- Owner/architect/contractor meetings,

- BIM execution plan and model-sharing protocols, and

- Lean collaboration techniques; and

- Coordination requirements with airport stakeholder groups (e.g., utilities, public affairs, asset management and commissioning).

5.4.2 Design–Assist: Getting Trades Involved Early

Design–assist contracts engage specialty subcontractors (e.g., mechanical, electrical, plumbing, building envelope, excavation support/underpinning) prior to the completion of the design to assist the architect or CM in the development of the design and construction documents. Although most commonly associated with CMAR delivery, design–assist services can also be adapted to DBB and DB to obtain early input from specialty trades.

For unique and/or complex projects, in which trade work constitutes a large portion of the overall project cost and scope, bringing specialty trades on board early in the design phase can help ensure the project gains the advantage of the trade contractor’s knowledge and experience at a competitive price and at a time when the contractor’s influence can be most effective.

In contrast to a more traditional approach, in which input from such trades may not be received until after construction has started and shop drawings are being produced, design–assist enables specialty trades to provide cost- or time-saving ideas at a time when such input can be most effective—as the design is still being completed—rather than after construction is underway, when incorporating such ideas may be more difficult. Design–assist offers the potential for fewer requests for information (RFIs), change orders, building code issues, and other potential conflicts that could affect the cost, schedule, or other project delivery goals.

To gain the full benefit of the input of design–assist contractors, owners usually retain them sometime during the schematic or design development phases, with the expectation that these contractors will work cooperatively with the design team to provide comprehensive design assistance, including

- Design development,

- Value management,

- Constructability,

- Cost estimating and final price determination,

- Schedule development,

- Permitting,

- Procurement,

- BIM, and

- Maintenance and life-cycle cost analysis.

The scope of a design–assist contract may be limited to such design–assist services, with construction services being subsequently bid out competitively. More often, design–assist contracts are structured so that the scope of work includes both the design–assist services as well as the construction of that scope of work. In such cases, the contracts are often based on a target value design (TVD) approach. TVD, as discussed in Section 5.5.2, is a process in which the project team strives to meet an aggressive, low target price. Rather than preparing the design, estimating the cost of that design, and then determining whether the owner’s budget can accommodate that cost, under TVD, the project team instead first establishes a preferred cost and then strives to prepare a design that can be constructed for this target price.

5.4.3 Collaborative Partnering

Partnering is a structured process that can be applied to projects of any size or type and to any PDM and that is designed to instill a culture of collaboration and teamwork in project participants. Partnering has been touted as having the potential to provide several significant benefits, including the following:

- Less-adversarial relationships,

- Increased stakeholder engagement and satisfaction,

- More timely and proactive resolution of issues, and

- Enhanced ability to meet project performance goals in terms of schedule, cost, and quality.

Formal partnering efforts typically involve engaging a trained partnering facilitator and developing a project charter, in which the project participants commit to working together to solve problems and to collaboratively seek solutions that benefit the project rather than a single participant.

ACRP Research Report 196: Guidebook for Integrating Collaborative Partnering into Traditional Airport Practices (Mollaoglu et al. 2019) discusses how to select, implement, and measure the effectiveness of various partnering tools.

San Francisco International Airport (SFO) has incorporated the use of what it refers to as “structured collaborative partnering” (SCP) as a core element of its project delivery paradigm. As described in the SFO publication Delivering Exceptional Projects: Our Guiding Principles (Neumayr 2014):

The purpose of SCP is to cultivate solid working relationships before problems and issues arise. By redefining the expectations around how all parties are to work together, structured collaboration can minimize such negative consequences as financial losses, damaged relationships, and unresolved claims.

Under its SCP model (which can be applied to any PDM but is particularly integral to SFO’s implementation of progressive DB), the airport is responsible for setting the vision and tone of the project and for driving expectations around the use of SCP. One such expectation is that the integrated project team (including owner, stakeholder, designer, and contractor representatives, as appropriate) will regularly participate in a series of structured and facilitated workshops. Table 5-2 shows the one-time and recurring workshops conducted as part of the SCP process at

Table 5-2. Partnering workshops conducted at SFO.

| Element | Planning Workshop | Kickoff Workshop | Executive Committee Workshops | Core Team Workshops | Stakeholder Workshops | Closeout Workshops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Establish the vision and goals for the project’s programming phase. | Define the structured collaborative partnering commitments and begin to establish a cohesive project team. | Ensure project remains on course. | Review and discuss project goals and status. | Provided forum for stakeholders to identify issues that might hinder project goals. | Review lessons learned to help ensure future projects run more smoothly. |

| Timing | Prior to all other meetings | Following the notice to proceed of industry partners | Monthly throughout project, in advance of core team and stakeholder workshops | Monthly throughout project (after the meeting of the executive committee) | Quarterly, in place of a monthly core workshop |

At or around project completion, following:

|

| Participants | Airport representatives | Integrated project team | Executive-level leaders and senior managers of the airport, construction manager, contractor, and designer | Key personnel of the airport; designer; and builder responsible for the management, implementation, and execution of the project | Executive committee, core team, and stakeholders | Executive committee and project team |

| Agenda items |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SFO. These workshops are intended to allow relationships and trust to steadily build in advance of any potential project issues and, if problems ultimately do arise, to provide a forum in which such issues can be discussed and resolved.

5.4.4 Stakeholder Engagement

Project stakeholders are individuals or entities who have a direct interest in the outcome of a project but who are not specifically involved in the delivery of that project, for example, adjacent landowners, local government, facility maintenance personnel, project funders, airline representatives, retail and concession tenants, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), FAA, fire, and police. Outreach to stakeholders is critical to all projects, but even more so when the airport is using alternative PDMs that may operate under a fast-tracked schedule with overlapping design and construction phases. The early and continued involvement of stakeholders reduces the risk of having to reconfigure designs to satisfy stakeholder needs. The more developed a project becomes, the more difficult it is to make changes to it.

Early stakeholder involvement reduces the risk of having to reconfigure designs or work that could have been prevented. It becomes more difficult to make changes to a project the more developed it becomes.

Project delivery teams should therefore have a clear plan for engaging with stakeholders to ensure any stakeholder input regarding needs, issues, and other operational considerations that may affect the design, phasing, or cost of the project is obtained at strategic points in the development of the project. A stakeholder engagement plan typically includes a list of project stakeholders and communication protocols. The list of stakeholders may be further classified or prioritized on the basis of

- Perceived power and influence (i.e., ability to sway the direction of the project),

- Area of interest (e.g., operations, maintainability, life-cycle cost, compliance, sustainability), and

- Project phase (e.g., needs identification design, construction, commissioning).

Communication protocols, which may vary on the basis of the stakeholder involved or the phase of the project, include

- Method of engagement (e.g., in-person workshop vs. email communication),

- Engagement actions (e.g., keeping informed vs. obtaining approvals),

- Frequency of communication, and

- Granularity of the information disseminated to each stakeholder.

5.4.5 Building Information Modeling

To further promote team integration, BIM can be used as a platform for collaboration throughout the project’s design and construction phases. BIM employs three-dimensional, real-time, dynamic building modeling software to model building geometry, spatial relationships, geographic information, and quantities and properties of building components. BIM can also be extended to include four-dimensional simulations to see how the facility is intended to be built for phasing/scheduling purposes, five-dimensional capability for model-based estimating, and six-dimensional capability for facilities operation.

BIM streamlines the processes for creating, reusing, analyzing, and sharing project information, thereby helping project teams to identify issues and resolve problems faster.

Working within a virtual BIM environment makes it more convenient to have a shared and collaborative approach to project delivery, in which participants are integrated into the team at the point at which they can bring the most benefit to the project.

The cost of incorporating design modifications and coordinating interdisciplinary design efforts escalates as the project progresses. BIM supports the team integration needed to shift more of the design effort and coordination toward the front end of a project’s delivery cycle, where there is more flexibility to make substantive changes at minimal cost impact to the project. When successfully implemented, BIM offers higher-quality information that is generally more

coordinated and reliable for better decision support. This allows project teams to be more productive in creating design solutions that are functional, cost-effective, and sustainable.

Before the start of the design phase, key members of the project team should meet to develop a BIM protocol (to the extent not already standardized by the owner) that considers questions such as the following:

- What building components and systems should be modeled (versus what information is more efficiently developed and conveyed by using traditional two-dimensional design tools)?

- What level of development is appropriate for each element, on the basis of the complexity of the project?

- Where and how will the model be maintained?

- What hardware and software requirements will be used to develop the BIM?

- What protocols will be used for naming conventions, data structure, version control, and archiving?

- Who will control the BIM and information within specific models?

- How will information on existing conditions be incorporated?

- When and how will information regarding constructability and cost be derived?

- How will RFIs, clarifications, shop drawings, and submittal information be incorporated?

- When and how will clash detection occur?

- How will the BIM be updated?

- Will a record model be required for project closeout?

These considerations are typically addressed as part of the development of a project-specific BIM execution plan (BIMxP) that is prepared in advance of the design phase. For CMAR projects, once the CM firm has been engaged, the BIMxP should be updated as needed to describe how the CM will be integrated into the project team.

5.4.6 Lean Approaches to Collaborative Planning and Problem-Solving

Overview

A growing number of airports are beginning to apply what is known as lean thinking to foster a more holistic approach to the design and construction process. Lean thinking entails

- Developing and managing projects through relationships, shared knowledge, and common goals;

- Breaking down and reorganizing traditional silos of knowledge, work, and effort by using a value stream approach;

- Changing the culture of a project and creating an atmosphere for innovation and improvement; and

- Promoting a learning environment and continuous improvement.

Tables 5-3 through 5-6 identify several tactical tools and practices that can be employed individually or in combination to achieve a lean project. It is beyond the scope of this guide to describe such tools in detail. For more information, interested readers are referred to the Lean Construction Institute (https://leanconstruction.org/) and its various books and publications, including

- Transforming Design and Construction: A Framework for Change (Seed 2017) and

- Target Value Delivery: Practitioner Guidebook to Implementation (Hill et al. 2016).

Organizations that have successfully implemented such lean techniques have reported lower costs, reduced construction times, enhanced productivity, and more efficient project management. Lean tools are also increasingly being used in close coordination with BIM to better align BIM usage with the project team’s production plan (for example, a phase pull can be used to inform the timing and BIM level of development needed to support design decisions).

Table 5-3. Organizational tools for lean design and construction.

| Tool | Why Use It? | How to Use It? |

|---|---|---|

| Conditions of Satisfaction (CoS) | ||

CoS are the metrics by which a project will be considered a “success.” For example:

|

|

CoS should be

|

| Big Room Approach (Mindset) | ||

A Big Room mindset takes a collaborative, cross-functional, and cross-organizational approach to organizing a project team’s activities and producing work product (in contrast to typical siloed and up-and-over work production cycles). Big Rooms can involve

|

|

|

| Focus (or Cluster) Groups | ||

| Focus groups are cross-functional and cross-organizational subteams consisting of designated representatives from the main project team who are charged with collaborating on the design, development or implementation of major project elements [e.g., the mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) or curtain wall system]. |

|

|

Table 5-4. Collaborative work planning tools for lean design and construction.

| Tool | Why Use It? | How to Use It? |

|---|---|---|

| Last Planner® System (LPS) | ||

|

The LPS is a managerial framework, developed by the Lean Construction Institute that uses a collaborative process by which project teams (e.g., owner, designer, contractor) plan and execute work activities in a manner that ensures the work is done when and how it is needed to support the efficient and cost-effective delivery of the project.

Note: Massport’s Last Planner® System Minimum Standards Guide tailors the classic Lean Construction Institute LPS approach to the way in which Massport delivers projects. (See Box 5-1.) |

|

LPS entails a disciplined approach to production planning that includes the following:

|

| Pull Planning | ||

|

Pull planning is a management method for advancing work only when the next-in-line customer of that work is ready to use it.

Instead of pushing a project through completion, pull planning establishes what is necessary to pull it toward completion. Pull planning is based on a request received from the downstream customer that signals that the work is needed and is to be pulled from the performer. Pull plans typically address either a specific time period or a group of activities leading to the accomplishment of a defined milestone. |

|

Pull plans are prepared by the actual members of the project team responsible for doing the work, typically during workshop sessions:

|

Table 5-5. Decision-making tools for lean design and construction.

| Tool | Why Use It? | How to Use It? |

|---|---|---|

| A3 Thinking | ||

| A3 thinking is a collaborative process management and improvement tool that can be used for problem-solving, decision-making, and reporting. It refers to the use of a one-page report prepared on an 11 × 17 sheet of paper that is used to focus project team members on resolving a specific problem and documenting the rationale behind various decisions and solutions. |

|

|

| Choosing by Advantages (CBA) | ||

|

CBA is a decision-making framework (often applied in conjunction with an A3 process and report) for determining and documenting the best value decision by systematically looking at the advantages of each option.

This approach can be particularly useful when multiple variables need to be considered before an informed decision can be made, as is often the case when multiple solutions exist but the best outcome is not readily apparent. |

|

CBA typically involves a trained facilitator guiding the project team through the following five phases of decision-making:

|

Table 5-6. Process improvement tools for lean design and construction.

| Tool | Why Use It? | How to Use It? |

|---|---|---|

| Plus/Delta | ||

| Plus/Delta is a continuous improvement activity performed at the end of a meeting, session, or project event to evaluate the meeting/session/event. | Promote a culture of continuous improvement. |

In the last 5–10 minutes of a meeting, two questions are asked, discussed, and documented for action as needed:

|

| Retrospective | ||

|

A retrospective is a structured working session in which the project team reflects on some portion of the work or process, reviews specific actions or events, assesses the plan against the outcomes, and commits to improve the next event.

In contrast to a conventional lessons-learned process, the retrospective process requires the project team to produce and follow up on an action plan. |

Facilitate continuous learning and improvement. |

On a regular basis, the project team holds a facilitated and structured session to discuss what on the project is working and not working. This is often done as an S/K/S process, in which the project team reflects on what it should

|

Transforming an organization, and its industry partners, into one that fully embraces lean project delivery will likely not occur overnight. Massport’s experience with lean design and construction is described in the next section.

Massport’s Lean Implementation Strategy and Transformation

Background. Massport’s Capital Programs and Environmental Affairs Department (CP&EA) develops and delivers Massport’s approximately $500 million annual capital program, which includes construction at Logan International Airport, Boston’s Seaport District and maritime facilities, Hanscom Field, and Worcester Regional Airport. In 2013, Massport CP&EA embarked on a lean implementation strategy to combine lean construction principles and techniques with BIM to promote and achieve

- Greater collaboration and communication within project teams at all levels,

- More robust stakeholder engagement in developing common goals and expectations consistent with project scope and budget constraints,

- More reliable cost estimates and budget tracking,

- More collaborative decision-making with direct stakeholder engagement,

- Decreased process waste by challenging teams to be efficient, and

- A continuous improvement atmosphere that encourages learning and innovation.

Approach. Massport’s CP&EA drove its lean transformation in the following three key areas:

- Collaborative work planning: LPS and pull planning exercises were introduced as tools to help teams develop, maintain, and adhere to a living work plan.

- Decision-making: Lean tools such as A3 thinking and CBA were promoted for use at key decision points within projects to help ensure more informed and timely decisions.

- Continuous process improvement: Tools such as Plus/Delta and retrospectives were used to foster a culture of continuous improvement in project teams.

When first piloting lean approaches in its CMAR projects, Massport found that project teams varied in their understanding and use of lean tools. As an enhancement to lean usage, Massport

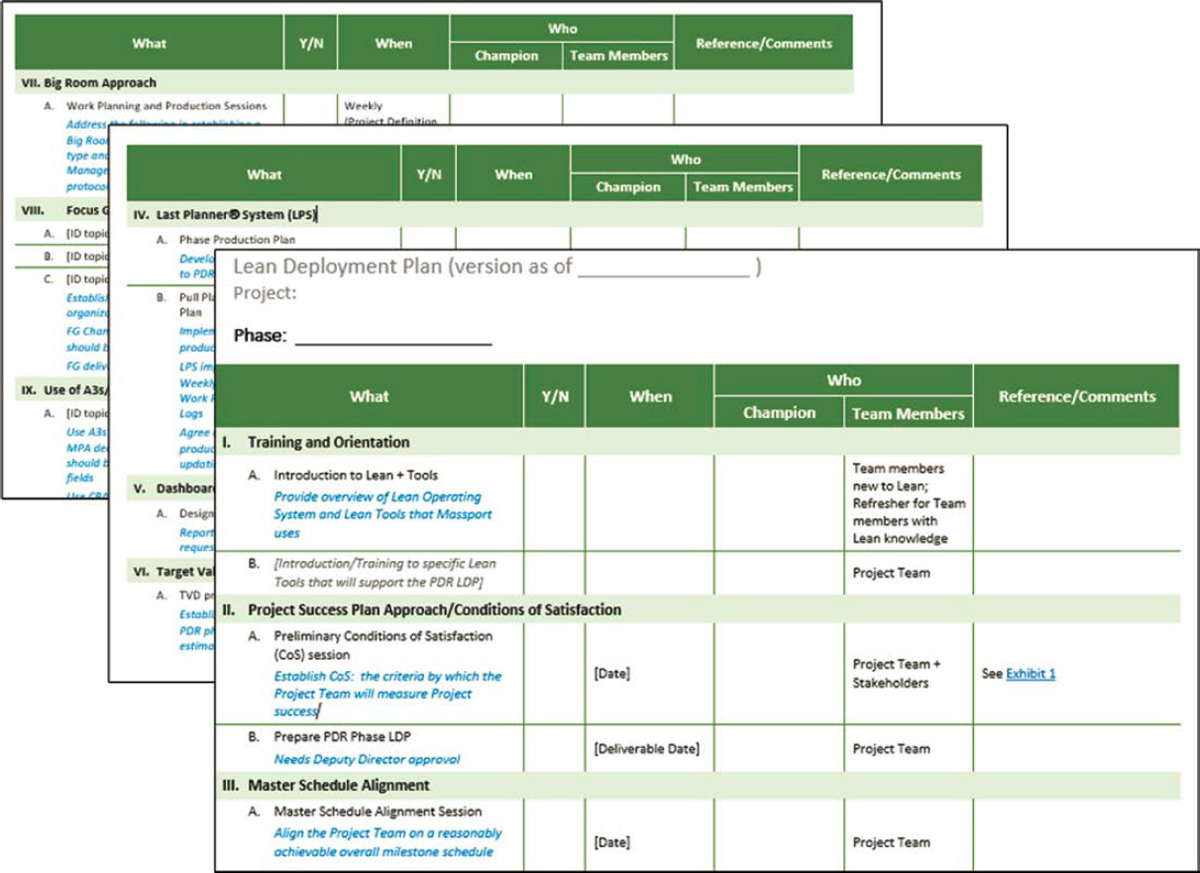

in 2018 therefore developed a template for its Lean Deployment Plan (Figure 5-1), which project teams were to fill out and update at the start of each project phase (project definition, preliminary design, final design, preconstruction, and construction).

Even though Massport did not at that point mandate use of lean tools, the Lean Deployment Plan required project teams to consider and make decisions on, which, if any, lean tools they would use, how such tools were going to be implemented, and who was responsible for their implementation. In 2018, Massport also started development of its Last Planner®System Minimum Standards Guide to set minimum requirements for the use of pull planning.

Results.

In 2019, Massport concluded, on the basis of implementation of Lean Deployment Plans and the Last Planner® System Minimum Standards Guide, that the level of maturity of the use of lean principles by project teams had reached the point where some lean tools could be contractually required as “the Massport way of doing business,” while other lean tools could remain optional for use. Massport thus added lean provisions to its procurement documents and its CMAR contracts. In general, the lean procurement provisions (RFQs and RFPs) covered qualifications requirements for lean experience and understanding, and the lean contract provisions, which were set forth in

an exhibit to the agreement (Figure 5-2), covered both mandatory and optional lean tools that Massport could select for use on projects:

- The mandatory tools (Last Planner® System, conditions of satisfaction, A3 process and report, choosing by advantages, and lean/BIM coordination) set a baseline for lean usage to promote consistency of lean usage across projects.

- The optional lean tools (Big Room approach, focus groups, target value design) allow flexibility for project teams to decide what additional lean tools would enhance project delivery, taking into consideration the level of experience and understanding of the project team.

5.5 Scope and Budget Management

When an alternative PDM is being implemented, an owner’s traditional practices for monitoring and overseeing project execution may require some adjustment. Use of the collaborative team-building techniques described in Section 5.4 can go a long way toward ensuring the project advances in a coordinated and orderly fashion, with minimal waste, particularly when PDMs that allow for early industry involvement are being used. Owner staff, however, must remain cognizant of their own role in the execution process. The design phase in particular is a critical area in which roles and responsibilities between the owner and its industry partners must be clearly defined. For example, with DB, owner staff need to understand that their design reviews should be limited to evaluating for compliance with the approved scope and design criteria and that asserting their own preferences might result in costly change orders.

Achieving the full benefit of alternative PDMs often requires a high level of owner participation to set expectations up front, continually reinforce project delivery goals, and track team performance against such goals.

The more collaborative PDMs, such as CMAR and PDB, offer the owner more flexibility to work with the project team to refine the building program and performance criteria as the design and project evolve. However, the owner should still be steering the project team toward achieving design freeze as early as possible to avoid the potentially costly and time-consuming design churn that often accompanies consensus-driven decision-making. Also critical, particularly for PDMs such as CMAR and PDB, for which a construction phase price may not be established until well after the contractor has been selected, are the methods used to monitor and control cost.

This section presents some additional project management tools that can be implemented to impart more discipline to the management of project scope and budget.

5.5.1 Cost Models

Multiple airports shared the lesson learned that the early development and regular updating of a project cost model can help keep a project on track with the owner’s budget objectives, particularly for projects without a fixed scope or price at the time of contractor selection. A cost model indicates the estimated project cost, typically broken down by specification sections and cross-referenced to specific trade packages. The intent is for the model to be structured in a manner that will facilitate the continual estimating of component and system costs via benchmarks, metrics, or detailed estimating.

Regular updates to a well-structured cost model provide the project team with actionable information as to how the project cost is trending as the design evolves.

Regular updates to the cost model are used to demonstrate whether the design is proceeding within the expected cost or whether adjustments are necessary to bring the project cost back in line with the owner’s budget expectations. Having near real-time access to such cost information while the design is progressing (as can be provided by a contractor as part of its preconstruction phase services) allows the owner and project team to make informed decisions before detailed design work begins, thus helping to minimize, if not avoid, cycles of design rework. The incorporation into the model of the results of project risk analysis—to the extent discrete risks can be monetized, as opposed to simple reliance on a general contingency line item—and the subsequent tracking of those risks to closure can further enhance the utility of the cost model.

5.5.2 Target Value Design/Delivery

Overview

In addition to applying some of the lean design and construction techniques described in Section 5.4.6 and maintaining a project cost model as described in Section 5.5.1, some owners have also begun to explore the use of TVD. Sometimes characterized as building (or designing) to a target cost, TVD entails the project team applying a disciplined management approach to the design process in which cost, schedule, and constructability are viewed as design constraints

and cost targets are used to drive innovation in designing a project that provides the best value to the owner.

Applied effectively, TVD

- Ensures the design phase progresses in a manner that will allow the project to be completed within the owner’s allowable cost and schedule,

- Promotes common understanding among all project participants of the design and performance criteria for the project, and

- Drives innovation and quality to increase value and reduce waste in all aspects of project delivery.

To obtain these TVD benefits,

- Designers must recognize that the design process should not occur in a silo and that value, cost, schedule, and constructability inputs are essential to achieving an integrated design process and

- The contractor and its key subcontractors must engage in meaningful constructability reviews and provide rapid and accurate cost and schedule evaluations throughout the design process as part of their preconstruction phase services.

A key element of the TVD process entails establishing a target cost (and associated schedule) for the project, typically as part of the project’s program definition phase. The target cost is set at less than the current estimate or best-in-class past project performance. The intent is for the target to generate the creative tension (e.g., more program elements yet less cost) needed to drive innovation and waste reduction in the design and construction process. On the basis of this target cost, the project team then applies a design-to-budget process instead of the conventional process of developing a design, estimating the costs of that design, and then applying VE principles as necessary to eliminate budget overruns.

The target cost should serve as a stretch goal that pushes the team to be truly innovative, as opposed to simply being more efficient in doing things the traditional way.

To accomplish TVD in a disciplined manner, the project team typically establishes TVD focus or cluster groups for different building systems or design elements, as appropriate, with a target cost allocated to each team. The TVD cluster teams then work to identify options that will reduce capital or life-cycle costs, improve constructability and functionality, or enhance operational flexibility consistent with the owner’s project goals. During this time, the design stays flexible while the project team tests assumptions based on rapid cost estimates provided by the contractor team and ultimately selects the best option for the project.

TVD Versus Value Engineering

TVD is often viewed as just another form of VE. However, these tools are quite different in approach and objective and should not be confused.

Traditional VE.

In a traditional VE process, the design team will develop a design, typically in isolation from contractor input. On the basis of a review of this design, the contractor will then offer VE comments or potential solutions to lower the cost of constructing that design. Because traditional VE does not occur until after the design is complete, incorporation of accepted VE suggestions may require additional design services or design rework.

TVD.

In contrast, TVD requires the design team to work collaboratively with the contractor and its key subcontractors (some of whom may be working under design–assist agreements, as described in Section 5.4.2) while the design is in development. The expectation is that the contractor team will provide continuous cost-estimating services to facilitate the assessment of various design options. Typically, to derive the most value and innovation from the process, multiple design options are carried forward, and design decisions are deferred until the last responsible moment, based on pull scheduling results.

5.5.3 Project Risk Management

All projects contain some uncertainty or risk that, if realized, could have an impact on the budget, schedule, scope, or other important project goals. When alternative PDMs are being used, the risk management process should be managed with a cross-organizational and cross-functional team approach. For example, the preconstruction services phase of a CMAR or PDB project could be used by the project team to collectively assess risks, identify the need to perform additional site investigations to further identify and reduce risks, and negotiate risk allocation prior to establishment of a construction phase price.

ACRP Research Report 116: Guidebook for Successfully Assessing and Managing Risks for Airport Capital and Maintenance Projects (Price 2014) provides various tools to assist project teams with evaluating and managing project risks.

ACRP Research Report 116 presents an iterative, step-by-step approach for managing risks that will allow the project team to identify and assess risks, determine those that are most critical, and develop and implement response strategies to help ensure project goals are met. Following are key steps in this process:

- Risk management planning—the process of developing an organized and comprehensive project-specific approach for identifying and analyzing risks, developing a risk response plan, continuously monitoring and assessing risks to determine how they may have changed, and assigning adequate resources to the risk management effort.

- Risk identification—the process of identifying and documenting the risks and opportunities that could significantly affect project performance.

- Risk analysis—the process of evaluating risk events in terms of the probability of their occurrence and their impacts (consequences) on cost, schedule, and other project performance goals. Risk analysis methods are broadly classified as being either qualitative or quantitative.

- Risk response—the process of identifying, evaluating, selecting, and implementing options to set risk at acceptable levels given project conditions and constraints. This includes the specifics of what should be done, when it should be accomplished, who is responsible, and what is the cost and schedule impact of implementing the selected option. General risk response strategies for responding to threats include acceptance, transference, mitigation, and avoidance (in contrast, strategies for responding to opportunities include acceptance, sharing, enhancing, and exploitation).

- Risk monitoring and control—the process of systematically tracking, evaluating, and reporting project performance and the effectiveness of the selected risk response actions against the risk management plan and established metrics.