From Lucid Stead: Prints and Works by Phillip K. Smith III (2019)

Chapter: From Lucid Stead: Prints and Works by Phillip K. Smith III

|

CULTURAL |

March 18 – September 13, 2019 |

From Lucid Stead

Prints and Works by

Phillip K. Smith III

From Lucid Stead: An Introduction

This exhibition features photographs (Focused Views), prints (Chromatic Variants), and a sculpture (Lucid Stead Elements) by California-based light artist Phillip K. Smith, III. Shown in this exhibition for the first time together, the works are inspired by Lucid Stead, Smith’s 2013 installation in Joshua Tree, CA where he transformed an existing homesteader shack into a mirrored structure that, by day, reflected the desert surroundings and, by night, shifted into a color changing projected light installation.

Smith creates large-scale temporary installations drawing on concepts of space, form, light, shadow, environment, and change. His practice is informed by his architecture training at Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. His works include The Circle of Land and Sky (2017) at the inaugural Desert X in the Sonoran desert, Open Sky (2018), in Milan’s 16th-century Palazzo Isimbardi, and Detroit Skybridge (2018), commissioned as part of Detroit’s Library Street Collective’s revitalization effort.

Producing extraordinary and communal encounters via installations that explore the transitory nature of light, Smith fosters inexpressibly human, immaterial, and unifying experiences that elude language and defy form, but can be undeniably felt. Through his pacing of color, reflection, and use of the environment as material, Smith encourages us to slow down and observe our surroundings in new ways.

This exhibition is sponsored by Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences

#LucidStead I @CPNAS ![]()

Artist Statement

Lucid Stead (2013) is about tapping into the quiet and the pace of change of the desert. When you slow down and align yourself with the desert, the project begins to unfold before you. It reveals that it is about light and shadow, reflected light, projected light, and change.

In much of my work, I like to interact with the sun’s movement so that the artwork is in a constant state of change from sunrise to evening. With Lucid Stead, the movement of the sun reflects banded reflections of light across the desert landscape, while various cracks and openings reveal themselves within the structure. Even the shifting shadow of the entire structure on the desert floor is as present as the massing of the shack, within the raw canvas of the desert.

The desert itself is as used as reflected light and is actual material in this project. It is a medium that is being placed onto the skin of the 70-year old homesteader shack. The reflections, contained within their crisp, geometric bands and rectangles, contrasts with the splintering bone-dry wood siding. This contrast is a commonality in my work, where I often merge precise forms with material or experience that is highly organic or in a state of change—something that you cannot hold on to, that slips between your fingers.

White light, projected from the inside of the shack outward, highlights the cracks between the mirrored siding and the wood siding, wrapping the shack in lines of light. This white light reveals, through silhouette, the structure of the shack as the 2×4’s and diagonal bracing become present on the skin of Lucid Stead.

The questioning of and awareness of change, ultimately, is about the alignment of this project with the pace of change occurring within the desert. Through the process of slowing down and opening yourself to the quiet, only then can you really see and hear in ways that you normally could not.

—Phillip K. Smith, III

Doubling Down

According to published surveys, you look in a mirror between eight and twenty-six times a day. If you are a male and you shave, you spend sixteen-and-a-half minutes on average in front of a mirror while shaving; if a woman, you may spend an average of fourteen-and-a-half minutes applying makeup and adjusting your personal experience in its presence. Artificial mirrors have been with us for at least 8,000 years, glass ones with metal backing for more than 2,000 years. Mirrors reverse the forward-to-backwards axis, which is why we think they reverse left to right. No matter, we are so adept at the mirror effect that we manage not to slit accidentally one’s throat while shaving, or to put out an eye while applying eye-shadow.

We picture mirrors in paintings and photographs, and clad entire skyscrapers in them, sometimes inadvertently cooking adjacent buildings as a result. We deploy them in periscopes and lasers, but also in optometrist and dentists’ offices, and carnival funhouses. Virtually every vehicle hosts at least one. As a result, it’s difficult to surprise us with a mirror, but the slender and elusive “Invisible Barn” by the architect studio stmpj that sits in a forest in the northern Sierra, and Doug Aitken’s full-size “Mirage” ranch house in the Swiss Alps above Gstaad are examples of contemporary artists putting mirrors on structures in hopes of helping encounter reality in unexpected ways.

Phillip K. Smith, III’s temporary installation “Lucid Stead’ is the most interesting of these interventions by several virtues. Smith was born and raised in the Mojave Desert, returning to his home terrain to practice architecture and make art after earning

Bachelor’s of Fine Art and Architecture degrees at the Rhode Island School of Design. His early sculptures and installations used architecture as their inspiration, sometimes incorporating mirrors and lights with stacks of interleaved material, but “Lucid Stead” adopted an actual building for its armature. Using an abandoned “jackrabbit homestead” cabin (the name comes from the American desert hares that inhabit the land), Smith profoundly destabilized what you thought of a mirror.

One of the last homestead movements in America, the Bureau of Land Management’s Small Tract Act of 1938 provided people with up to five acres in the Mojave’s Morango Basin for only a few dollars if you improved the property (most often by building a cabin of at least 400 square feet) within three years. It was an attempt to monetize what the government considered useless land, but veterans returning from WWII spurred a land rush and as late as 2004 there remained 2,000 of the simple structures. Many were one-room bilateral tripartite cabins—four walls and a roof fronted by a door with a window on each side. It’s the most common face of a domicile in American architecture.

Smith wrapped mirrored bands around the house that alternated with the original slats of wood siding. The effect in the highly isotropic environment of the Mojave—where everything looks much the same in all directions—was that you thought you were looking through the house. It was difficult to remember that you were looking in a mirror, a bit as if the Invisible Man had taken off alternating strips of bandages and revealed not what was behind him, but behind you. The effect produced an affect that left you betwixt and between. The mirrored structures by stmpj and Aitken retained their visual integrity, despite open windows and doors through which you could see the landscape on the other side of the house. But the gestalt of “Mirage” as a house was so compromised by alternation of mirrored and un-mirrored planks that you had to concentrate to reassemble its condition as a house. You lost track of time, could literally get dizzy while performing this reverse prestidigitation, and in short experienced what you least needed in an isotropic space: disorientation. On the other hand, it was safer and more interesting than doing drugs.

Additionally, Smith took an historical building as his armature, which meant you found yourself moving back and forth in time, between the old weathered boards and the slick mirrored bands, between the Old West and the Post-Rural, between homesteading and art-going. The effect at night was, if not as disorienting, even more complicated. Smith used LEDs to turn the windows and doors into solid panels of blue, red, yellow, green, orange or purple that slowly rotated through the palette. In between the boards and bands of mirrors white light leaked out, making visible the diagonal two-by-fours inside and holding up the walls. What by day looked like slices of a house hovering improbably over the desert by night became something both more solid but oddly eerie.

Smith’s work has been compared to that of the earlier masters of the Light and Space movement in Southern California during the 1960s and early ‘70s, artists such as James Turrell, Robert Irwin, and Larry Bell. The linkage is apt, their spare geometries and use of both natural and projected light tinkering with the permeable boundaries of cognition and reality. Manipulating materials to make the world at once strange and beautiful so that we can perceive more of it is the useful task of an artist. Rearranging what we think a mirror does in the Mojave—an environment so alien to us that we stage science fiction movies on it because there is no objective correlative to contradict the imagination—is to double down on the question of sight itself. If we think that what we see is what we believe, then Phil Smith has given us every chance to question that assumption.

—William L. Fox

Lucid Stead: Chromatic Variants

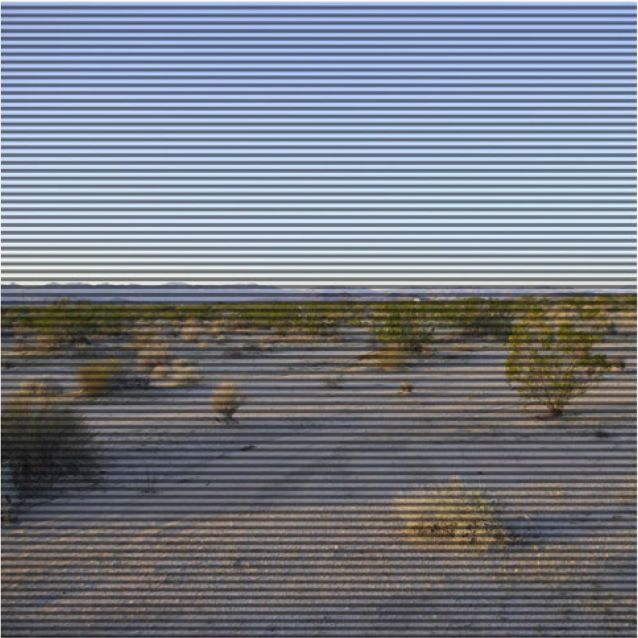

The Chromatic Variants series features tight arrays of transparent colored lines that separate and merge an image of the desert with its color-tinted reflection. From a distance, each image of the desert appears as a color-tinted still of the Lucid Stead environment caught in a specific moment in time during the shack’s changing color spectrum. A closer look reveals the colored bands separating out the view of the desert environment, recalling Smith’s use of the surrounding landscape as a medium placed across the banded, mirrored surface of Lucid Stead. Smith’s choice of six colors echoes the spectrum of colored light used in the four windows and doorway of Lucid Stead, while his use of white and black pays homage to the changing of the desert light from the brightness of the day to the black of the night.

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 18 × 18 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 18 × 18 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 18 × 18 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 18 × 18 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 18 × 18 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 18 × 18 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 18 × 18 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 18 × 18 inches

Lucid Stead: Focused Views

Phillip K. Smith, III took this series of photographs in 2013 prior to closing the Lucid Stead installation. The photographs are detailed and cropped views of the homestead shack, drawing attention to the relationship between the weatherworn wood, reflection, and the environment. The day after Smith took these photographs, he decommissioned the work by returning the cabin to its original state with one exception: He did not reattach the original wood siding he had removed, but rather kept it catalogued in his studio. These woods slats would become the originators of the Lucid Stead Elements sculptures, one of which was also featured in the exhibition at the National Academy of Sciences.

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 30. 5 × 44 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 44 × 30.5 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 30.5 × 44 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 44 × 30.5 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 30.5 × 44 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 44 × 30.5 inches

2013-2019

Archival pigment print, 30.5 × 44 inches

2017

Brushed anodized aluminum, glass, acrylic, wood, Lucid Stead original siding, LED lighting, electrical components, Lucid Stead color program, 47 × 87.5 × 6 inches. Collection of Rodney D. Lubeznik and Susan D. Goodman.

This sculpture is composed of the Lucid Stead installation’s raw elements—the original wood siding, the mirror, the white light, the 2×4 structure, and the shifting color—contained within a crisp aluminum frame. This sculpture is composed of the Lucid Stead installation’s raw elements—the original wood siding, the mirror, the white light, the 2×4 structure, and the shifting color—contained within a crisp aluminum frame. Its color scheme is inspired by the color-changing light projected onto Lucid Stead at night.