Understanding Airport Air Quality and Public Health Studies Related to Airports, Second Edition (2024)

Chapter: 4 Air Quality Health Impacts and Risks

CHAPTER 4: Air Quality Health Impacts and Risks

This chapter serves as a primer on understanding potential air pollutant health impacts and health risks associated with airport operations.

4.1 POLLUTANT HEALTH IMPACTS OVERVIEW

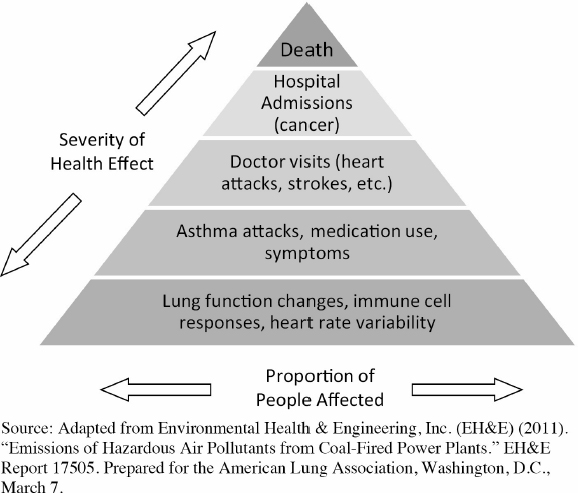

Each of the pollutants targeted in this report, with the exception of UFPs, can be categorized as either a criteria pollutant or a HAP (also referred to as air toxics) or as both criteria pollutants and HAPs (e.g., lead is regulated as a criteria pollutant, but lead-based compounds are on the EPA’s HAPs list). Each of these pollutants has health effects that range from mild to severe chronic and acute health effects, as well as premature death. Figure 4-1 provides an overview of the population proportions associated with the severity of health effects—in general, the more severe the effect, the smaller the proportion of the population affected. The figure describes different degrees of health effects, and it should be understood that different pollutants will have different health impacts and levels of severity. The following sections describe the potential health effects of each pollutant.

There are six (6) criteria pollutants. Additional information related to the health effects of the criteria pollutants is available on EPA’s Integrated Science Assessments (ISAs) website (at www.epa.gov/isa). A discussion of concerns over the public health impacts of these pollutants follows:

- Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless and odorless gas that can cause various physiological damages by displacing oxygen in the bloodstream. At high concentrations, CO has known health effects including dizziness, unconsciousness, and death. At lower concentrations more typical of ambient settings in the United States, individuals with cardiovascular disease are at risk of myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) or other exacerbations.

- Lead (Pb) is a soft, malleable metal in the “heavy metal” category. Lead is a concern for its ability to cause a range of neurological damage from all exposure pathways (inhalation, ingestion, and dermal contact). EPA (2023) notes that lead exposure pathways “may involve media other than air, including indoor and outdoor dust, soil, surface water and sediments, vegetation and biota. The human exposure pathways for lead emitted into air include inhalation of ambient air or ingestion of food, water or other materials, including dust and soil, that have been contaminated through a pathway involving lead deposition from ambient air.” The EPA acknowledges that once taken into the body, lead distributes throughout the body in the blood and is accumulated in the bones. Depending on the level of exposure, lead can adversely affect the nervous system, kidney function, immune system, reproductive and developmental systems, and the cardiovascular system. Lead exposure also affects the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood. The lead effects most likely to be encountered in current populations are neurological effects in children. Infants and young children are especially sensitive to lead exposures, which may contribute to behavioral problems, learning deficits and lowered IQ. Although monitoring data has shown that lead concentrations are generally below the NAAQS at U.S. airports, lead has no minimum impact threshold, and studies have found elevated blood lead levels in children living near airports.

- Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is one of the nitrogen oxides (NOx) that is part of a family of gases, mainly represented by nitrogen oxide (NO) and NO2, that can contribute to respiratory disease exacerbations. In addition to its direct health impacts, NOx is well known as a precursor to ozone formation. Furthermore, NOx also contributes to the formation of nitrate aerosols that can have respiratory and cardiovascular health effects.

- Ozone (O3) is a pollutant that generally is not directly emitted from most sources. Within the troposphere, it is formed through a complex interaction (chemical reaction) mainly involving NOx and VOCs in the presence of sunlight. Ozone can contribute to respiratory health effects through inflammation of airways and decrements in lung function, with evidence of increased respiratory symptoms among sensitive individuals such as asthmatics and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, as well as evidence of increased hospitalizations and premature deaths. Because of the formation of ozone from directly emitted pollutants (from many different sources) within a relatively large area, ozone is characterized as a regional issue even though it is a local air quality concern.

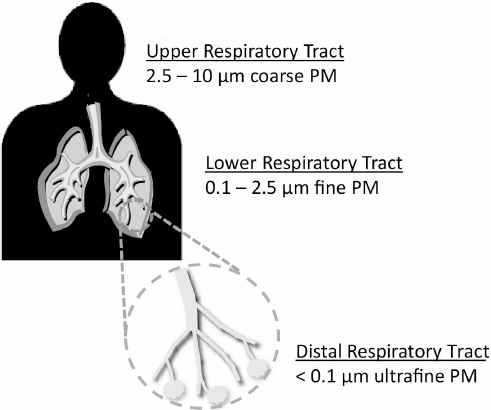

- Particulate matter (PM) is tiny solid, liquid, or mixed solid and liquid particles suspended in the air. These are of concern since ambient concentrations of PM have been shown to be correlated with serious respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses and premature mortality. PM sizes (aerodynamic diameters) range from greater than 100 µm to the ultrafine range of below 0.1 µm. The smaller the size, the deeper these particles are able to penetrate into the respiratory system, possibly even resulting in blockages of the gas–blood interfaces within the lungs. Figure 4-2 provides an overview of the portions of the respiratory system affected by the different PM size ranges. While the discrete PM size ranges shown generally correspond to different degrees of respiratory penetration, it should be understood that different size ranges can be deposited throughout the respiratory system. PM with a size range of 10 µm or less are referred to as PM10 and those with a size range of 2.5 µm or less are referred to as PM2.5. NAAQS concentrations are currently only specified for these two size ranges. Other PM types and components include UFPs, nitrates, sulfates, and black carbon (BC). Also known as elemental carbon (EC), BC is composed

of pure carbon clusters and is differentiated from organic carbon (OC), which is composed of organic compounds. BC is a significant contributor to the health effects caused by PM2.5 and UFPs. Nitrates and sulfates can penetrate deep in the respiratory system and can also react with other chemicals to form harmful compounds (e.g., acids).

While not a criteria pollutant like PM10 and PM2.5, UFPs are of particular concern at airports due to elevated concentrations near aircraft operations. UFPs have more aggressive health complications compared to larger PM sizes. This is for four main reasons (Ali, et al. 2020):

- Particle number counts are dominated by UFPs. Long-term and repeated exposure is inevitable. Public health studies demonstrate even at low concentrations, constant exposure to UFPs is toxic over a lifetime.

- UFPs are so small they have higher pulmonary deposition. UFPs bypass the human body’s filtration PM defense. The smaller the particle diameter, the higher the toxicity.

- UFPs are more inflammatory than larger PM sizes. UFPs translocate to essentially all internal organs and lead to cardiovascular disease, lung inflammation, hypertension, and birth defects.

- Aged UFPs coagulate with other toxic compounds, such as toxic metals, increasing their health implications.

- Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is a sulfur oxide (SOx). SOx refers to a family of gases mainly represented by SO2 that can act as irritants to the respiratory system and can contribute to asthma attacks and other health outcomes. As with NOx, concerns about SOx often relate to its ability to form sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere, with the corresponding health effects seen for fine PM.

HAPs are generally defined as those pollutants that are known or suspected of being able to cause serious health effects such as cancer, or birth defects. The EPA maintains a list of close to 200 HAPs comprised of VOCs, aldehydes, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), dioxins, furans, metals, acids, etc. A discussion of the formation and concerns over these pollutants follows:

- Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are comprised of a large group of carbon-based compounds with relatively high vapor pressures. The EPA further defines these as chemicals that participate in atmospheric photochemical reactions. They are emitted through evaporation from certain operations (e.g., painting, dry cleaning, solvent usage, etc.) and through incomplete combustion of fossil fuels. Indoor concentrations of VOCs are usually higher than outdoor concentrations—up to 10 times higher. Health effects depend on the specific species as well as exposure duration, but some short-term effects may include headaches, nausea, sore throat/eyes/nose, etc. Long-term effects may include cancer. Examples of VOCs include benzene, toluene, xylene, and 1,3-butadiene.

- Aldehydes and ketones are subsets of VOCs. Sometimes they are treated separately, which is in part due to the different methods required to measure these compounds. Both groups of compounds are made up of a double-bonded carbon-oxygen core (C=O). An aldehyde has at least one hydrogen bonded to the carbon atom while a ketone has two hydrocarbon groups attached to the carbon atom. Aldehydes are used in production of commercial applications including the production of alcohols, resins, detergents, perfumes, etc. Ketones have industrial uses as solvents, polymer precursors, and pharmaceuticals. As VOCs, both groups have relatively high vapor pressures, and their health effects are similar: irritation of the eyes and air passages under short-term exposure and lower concentrations. Long-term exposures and/or high concentrations can cause depression of the central nervous system and cancer. Examples of aldehydes are formaldehyde, acrolein, and acetaldehyde. Examples of ketones are acetone and acetophenone. Methyl ethyl ketone (MEK) is also a ketone but not a HAP—EPA removed this from their official list.

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are comprised of a group of compounds that generally have more than two benzene rings (a ring of six carbon atoms). They tend to stick to solid particles (e.g., soot) and are formed from incomplete combustion processes such as those from coal burning, automobile gasoline combustion, forest fires, and coke and coal tar processing. Animal testing has indicated that it is reasonable to expect PAHs to cause birth defects and cancer. Examples of PAHs include anthracene, benzo-a-pyrene, naphthalene, and chrysene. Of these, only naphthalene is currently listed on the EPA HAPs list.

- Dioxins and furans are comprised of a family of toxic substances that are similar in chemical structure and more formally referred to as polychlorinated dibenzo-para-dioxins (PCDDs) and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs). In addition to exposures through ingestion of food containing these compounds, exposures through inhalation of emissions from incineration (e.g., of municipal solid waste), copper smelters, cement kilns, coal-fired power plants, etc., are common. Potential health effects include birth defects, suppressed immune system, changes in hormone levels, and cancer. On the EPA HAPs list, these pollutants are listed as 2,3,7,8-Tetracholordibenzo-p-dioxin and dibenzofurans.

- Metals make up a small but important portion of the EPA HAPs list. Either in elemental form or as part of a compound, they can typically be emitted as PM from combustion sources including power plants, industrial operations, and ore refining. Three of the common metals are mercury (Hg), Pb, and chromium (Cr). Exposure to air emissions of mercury can result in various disorders including tremors, emotional changes, neuromuscular changes, changes in nervous response, and reductions in cognitive function. As previously indicated, exposures to lead can result in neurological damage, high blood pressure and hypertension, memory and concentration problems, muscle and joint pain,

- Acids make up a small subset of the EPA HAPs list, and hydrochloric acid (HCl) and hydrogen fluoride (HF) are two of the more well known HAPs. In addition to being used in various industrial activities such as refining ore, metals processing, glass etching, and aluminum production, they also can be generated through combustion of coal and other fuels containing chlorine (Cl) and fluorine (F). Acute health effects of these acids are similar in that they are corrosive and can cause serious damage to the respiratory system. Chronic effects for HCl include gastritis, bronchitis, and dermatitis as well as hyperplasia of the nasal mucosa, larynx, and trachea. HF chronic effects include increased bone density and damage to the liver, kidneys, and lungs.

and reproductive problems (in both adult men and women), lower IQ, damage to the brain and nervous system, learning and behavioral difficulties, slow growth, hearing problems, and headaches in children. Air exposure to Cr (III), the most common form of chromium in the air, can result in damage to the respiratory system. Exposure to Cr (VI) can result in more serious respiratory damage, as well as lung cancer.

To ensure no misunderstandings regarding these health effects, it should be noted that while the descriptions provide a comprehensive view of the current understanding of health impacts by pollutant type (or category), they do not directly indicate the risks associated with airport air quality impacts. Other details such as emission concentration levels and exposure time need to be taken into account and are discussed in the next section.

4.2 HEALTH RISK FACTORS

As defined by the EPA (see www.epa.gov/risk) health risk is “the chance of harmful effects to human health or to ecological systems resulting from exposure to an environmental stressor” where stressors are described as “any physical, chemical, or biological entity that can induce an adverse effect in humans or ecosystems.” Characterizations of risk are accomplished by conducting both exposure pathway assessments (how the pollutant interacts with the population) and dose-response assessments (how much of the pollutant is required to cause harm to an individual). These are general definitions used to describe risk for environmental impacts.

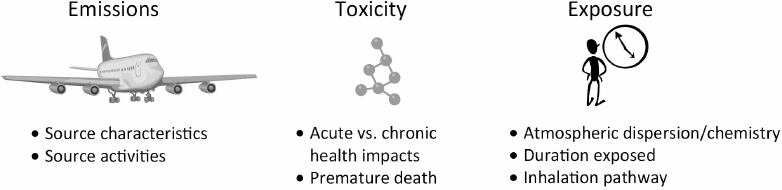

For air quality, health risk can be described as being influenced by three components: emissions, exposure, and toxicity. As indicated in Figure 4-3, these components encompass details regarding the source, pollutants, and the exposed public. The emissions of each pollutant depend on source characteristics. Source characteristics include emission factors (or rates) that are dependent on type of emissions source, equipment age, emissions control, and other factors. Toxicity is the degree to which a pollutant can harm a human being. Toxicity is characterized differently for criteria air pollutants versus HAPs. For criteria air pollutants, concentration–response relationships are generally constructed from epidemiological literature. These epidemiological studies typically contain concentrations representative of the current range of concentrations in the United States, and the concentration–response functions are applied as continuous functions to quantify incremental health effects of concentration changes. For HAPs, conventional risk assessment differentiates between carcinogenic effects and non-cancer effects, with the presumption that most carcinogens demonstrate low-dose linearity and that most non-cancer health effects display a putative population threshold. There are an increasing number of counterexamples that contradict this model, but most health risk assessments to date maintain this structure. Within the structure, for non-cancer health effects, inhalation RfCs are used. For

carcinogenic effects, unit risk factors are used. The EPA defines these terms as follows (see https://www.epa.gov/risk/conducting-human-health-risk-assessment-tab-3):

- RfC: An estimate (with uncertainty spanning perhaps an order of magnitude) of a continuous inhalation exposure of a chemical to the human population (including sensitive subpopulations), that is likely to be without risk of deleterious effects during a lifetime.

- Inhalation Unit Risk: The inhalation unit risk is the upper-bound excess lifetime cancer risk estimated to result from continuous exposure to an agent at a concentration of 1 µg/m3 in air for a lifetime.

Exposure encompasses both the pathway leading to the interaction between pollutants and the exposed population (i.e., concentrations experienced by the population) as well as the duration of the interaction. This is partly dependent on how pollutants disperse in the atmosphere and undergo chemical conversions to form other pollutants. It also is dependent on the size and activities of the local population and their locations.

In general, the health impacts from specific sources can be evaluated from either an individual perspective or a population perspective, and this holds for airport emissions as well. In the former case, the influential factors will be those that cause an individual to have greater risk from airport emissions than other individuals. In the latter case, the influential factors will be those that cause the public health burden from airport emissions to be greater. The factors will overlap but will not be identical.

From an individual perspective, proximity to the airport is clearly the dominant factor, although not necessarily in a simple distance-dependent fashion. Multiple studies indicate that being immediately downwind of a primary departure runway significantly increases exposures to multiple combustion pollutants, including UFPs, NOx, and BC. However, some studies indicate the potential for exposure over a fairly broad geographic area, especially related to arrivals—appreciable impacts can be observed more than 1 km from the airport, in a manner that is not strictly distance-dependent. The common influence of wind direction on aircraft movement patterns and plume dynamics creates challenges in interpreting monitoring data, but location relative to prevailing winds is clearly an important factor for individual risk. When spatiotemporal patterns differ across pollutants, which locations are most important from an individual health perspective are more difficult to ascertain, but evidence shows similar patterns across most pollutants with major public health implications.

From a population perspective, proximity and prevailing winds clearly influence the population health burden from airport emissions as well, but population density and spatial patterns of at-risk populations also must be considered. For example, pollutants such as fine PM (with

significant contributions from secondary formation) may have public health impacts that can span hundreds (or thousands) of kilometers. Thus, even if individual health impacts may be greatest at relatively close proximity to an airport, the public health impacts will be spread over a very large geographic area where the characteristics of the exposed population needs to be taken into account. That is, health impacts will be influenced not only by exposures, but also health status and other factors that make individuals or subpopulations more susceptible to the effects of air pollution. Elderly individuals and young children, as well as those with pre-existing respiratory or cardiovascular disease, are generally considered to be at greatest risk. Thus, population-based health assessments that take into account the exposed area and population characteristics may show differing results from an individual perspective where distance is the major factor.

Two general approaches can be used to estimate the public health burden associated with either an individual source (such as an airport) or a source category (such as LToO emissions). Epidemiological investigations involve developing new associations between exposures and health outcomes for a defined population, which can be interpreted as causal given supporting evidence from other epidemiological and toxicological studies. There have been numerous epidemiological studies evaluating ambient air pollution and its effects on respiratory and cardiovascular health, and the methods for conducting these studies are well established in the literature. However, epidemiological studies rarely associate air pollution specific to aviation with health outcomes. This is both because the contribution from aviation to ambient air pollution is generally small and because the pollutants associated with aviation are similar to those from vehicle traffic and other local combustion sources. There have been a limited number of occupational epidemiological studies of airport workers, which can better capture exposures specific to the airport environment but may not generalize to the public given differences in exposure levels and health status. Airport employees can potentially face some unique exposure concerns. Their exposure to fuel pollutants, such as benzene, toluene, and chlorinated compounds, would be dependent on their work schedule and job location.

Because direct epidemiological studies of air pollution specific to airports are generally impractical, it is far more common to use health risk assessment methods to quantify the health impacts of airport emissions. These methods typically involve bottom-up analyses linking airport emissions inventories with atmospheric fate and transport models, yielding estimates of the marginal contribution of airport emissions to ambient air quality across a region. These contributions are then linked with concentration–response functions for mortality and morbidity, derived from the general air pollution epidemiological literature. In other words, air pollution epidemiology provides the association between specific pollutants and health outcomes, and this evidence is assumed to be applicable to airport-related air pollution. For pollutants that do not differ by source, this approach has fewer uncertainties, beyond exposure assessment uncertainties and general concerns about whether the epidemiological evidence can be interpreted as causal. For fine PM, where the composition from aviation may differ from the ambient composition in a manner that influences health effects, there are additional uncertainties. However, as noted in EPA’s Supplement to the 2019 Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter (U.S. EPA, 2022), “…the evidence does not indicate that any one source or component is more strongly related with health effects than PM2.5 mass.” Therefore, the application of ambient air pollution epidemiology to determine contributions from specific source categories is a well established and appropriate approach in the health risk assessment literature. Constituent-specific epidemiology could be used when available and based on statistical models appropriate for health risk assessment.

Usage of sustainable alterative jet fuels (AJF) is expected to increase significantly in the near term as a key element of airline sustainability plans and goals. Sustainable AJF is made from non-petroleum feedstocks including vegetable oils, lignocellulosic crops, residues and waste, and sugar crops. When compared to petroleum-based jet fuel, AJF reduces aircraft emissions of PM2.5. (Arter 2022).