Implementing Machine Learning at State Departments of Transportation: A Guide (2024)

Chapter: 2 Roadmap to Building Agency Machine Learning Capabilities

CHAPTER 2

Roadmap to Building Agency Machine Learning Capabilities

Overview of the Roadmap

This guide adopts the high-level roadmap in Figure 1 as a framework for building agency ML capabilities, starting with an ML pilot project. The roadmap consists of 10 steps and includes a loop from Step 5 to Step 2 to emphasize the iterative nature of the ML development and implementation process. This roadmap is broken down into 10 steps:

- Step 0: Develop Understanding. Develop an understanding of ML key concepts and applications in transportation. This step summarizes what is needed to develop an ML model, highlights differences between ML and traditional methods that agencies are familiar with, and summarizes core and emerging ML concepts. It also includes examples of how ML has been used successfully in transportation so far as well as a discussion of ML techniques expected to impact transportation in the near future, such as large language models (LLMs). It is labeled as “Step 0” for two main reasons: (1) it assumes some agency staff may already understand the basics of ML, and (2) in true data scientist fashion, the roadmap is indexed at zero.

- Step 1: Identify Use Cases. Identify candidate transportation use cases where ML could support agency needs. This step discusses primary ML capabilities useful for transportation use cases (i.e., detection, classification, prediction) and includes examples of the types of transportation problems that can potentially be solved by ML methods, drawing on agency success stories and the literature.

- Decision Gate #1. After getting a sense of the landscape and possibilities of ML, the agency is faced with its first major decision gate: is ML a suitable approach for one or more of our agency’s needs? If so, in what capacity? This decision gate includes a checklist to help agencies decide whether ML is a feasible and desirable approach for one or more of their needs, based on the main criteria of suitability and maturity and their assessment of candidate transportation use cases.

- Step 2: Assess Gaps. Assess the availability of current resources to support ML and any gaps, including data, data storage, computing, workforce and organizational considerations, funding, and other considerations, including privacy and policies.

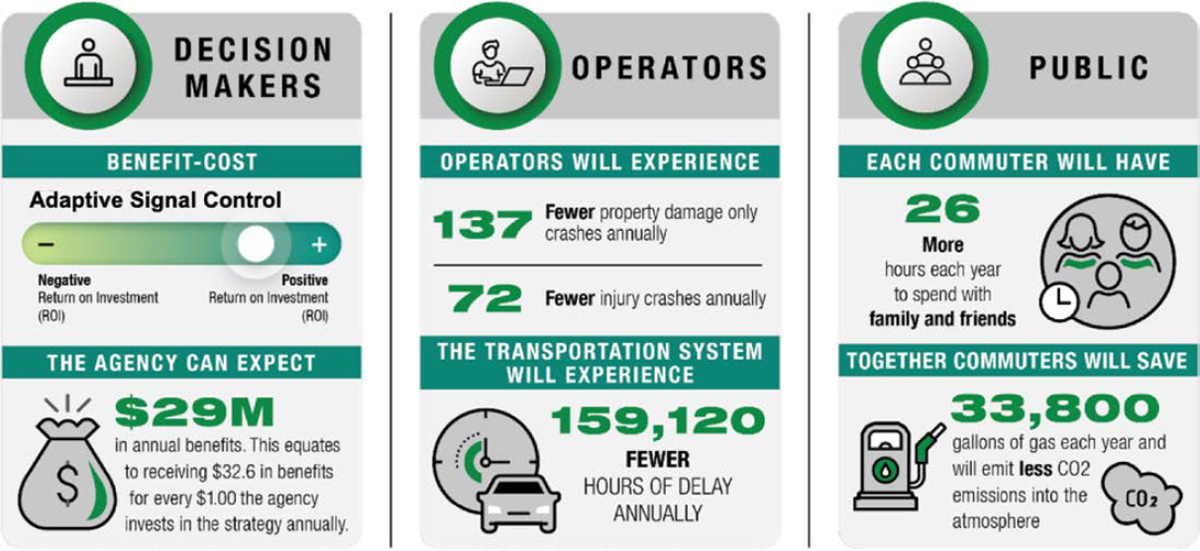

- Step 3: Build Business Case. Build a business case to secure leadership buy-in. This step discusses best practices in building a case for leadership to pursue an ML pilot project to support broader agency capabilities. It also includes information on identifying the value proposition of leveraging ML, including potential benefits and return on investment (ROI), as well as spreading awareness of uncertainties, potential risks, and costs to different stakeholder audiences.

- Decision Gate #2. The agency team will need to decide if and how to plan an ML pilot project given the resource availability and gaps identified in Step 2 and the leadership appetite from Step 3. If a “go ahead” decision is made, options may include executing the entire ML pipeline and developing all code in-house, leveraging available open-source code and applying it to

- the identified use case, or acquiring proprietary services, data, software, and/or consulting to support one or more aspects of the pilot. This step includes important questions to help teams decide which option to pursue for the pilot and summarizes the different benefits and risks of each approach.

- Step 4: Plan Pilot. Plan the ML pilot project, including the pilot scope, schedule, and budget. This step includes a detailed hypothetical example of pilot scope planning for a transportation asset management use case. It also includes important best practices, lessons learned, and examples concerning pilot schedule and cost considerations.

- Step 5: Execute Pilot. Execute the ML pilot project, including one or more aspects of the ML pipeline if the agency plans to build a custom model. During pilot execution, the agency may discover they need more data or other supporting elements for the project to improve model performance or system integration. Therefore, the roadmap incorporates a loop back to Step 2 to illustrate this iterative process.

- Step 6: Communicate Results. Communicate the results of the ML pilot. At this stage, the team should share the results of the pilot project, including relevant evaluation metrics, with others across the agency to spread awareness and build buy-in.

- Step 7: Scale Deployment. Scale from a pilot to a larger deployment. If the pilot project demonstrates promising results, it can be scaled by location, time, user base, and/or scope into a larger deployment.

- Step 8: Operations & Maintenance. Conduct operations and maintenance (O&M) of the newly deployed system. It may be helpful to assign one or more team members to be responsible for overseeing regular O&M for the ML application, which includes monitoring the input data and the ML model’s performance for signs of drift. Additionally, it is crucial to consider the deployed system’s lifecycle costs and secure ongoing funding to ensure it keeps operating smoothly.

- Step 9: Expand ML Capabilities. Continue to expand ML capabilities across the agency. This includes building out a broader enterprise AI/ML strategy and enterprise data management strategy, building workforce capabilities and training staff, fostering a data-driven culture at the agency, and collaborating within and across agencies.

Step 0: Develop Understanding

Introduction to ML Approach

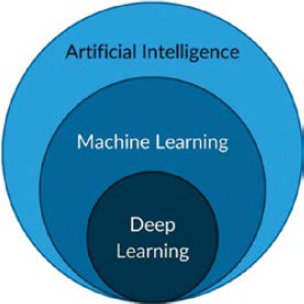

ML is a subfield of AI (Figure 2) that encompasses a wide variety of methods, ranging from simpler models like decision trees to DL or complex neural networks (NN) with billions of parameters. ML models fundamentally learn from data or examples. Rather than relying on explicit programming, ML models discover complex patterns through a model training process. Their applications include extracting insights from data, finding correlations among variables, predicting likely outcomes from given inputs, finding optimal strategies for decision-making, and so forth. Furthermore, ML models can adapt to new data and improve their learning over time without human intervention, which makes them effective for complex tasks where conventional algorithms might not be feasible.

While simpler models such as decision tree learning are considered part of ML, they prioritize interpretability and understanding of relationships between variables, whereas more complex models (e.g., deep NN) focus on predictive accuracy. One could even argue that linear regression is a rudimentary form of ML; however, this text compares classical models, such as linear regression, to more complex ML models. When referring to ML in this text, we are referring to these more complex techniques unless otherwise indicated. ML models, primarily those based on deep NN, have evolved rapidly within the last 10–15 years, with breakthroughs in image processing and recognition. Advanced deep NN architectures can now outperform humans in various board and video games as well as image and object recognition (Silver et al. 2017; Purves 2019; Payghode et al. 2023). These advancements rapidly catalyzed applications of AI/ML in almost all industries, including transportation.

ML models differ from more traditional statistical learning models in their approach to solving problems. In traditional statistical learning methods, the focus is on understanding relationships between variables or making inferences about some parameters of interest, whereas in ML the prediction accuracy is the central notion. ML models are designed to make the most accurate predictions possible when given new data – data not used in training the model. The model

training process involves finding the best set of parameters that will produce the most accurate results when applied to new data. Complex ML models, such as deep NNs, generally improve their predictive accuracy when provided with larger datasets. More technical details about the development process of ML can be found in the discussion of Step 5 in this guide.

Figure 3 shows several key aspects distinguishing ML models, especially complex deep NNs, from more traditional models (e.g., linear regression). These aspects include the following:

- Learning from data: Traditional models start by assuming a fixed form (e.g., a linear relationship) and attempt to find relations in the data matching the assumptions. On the other hand, ML models can adapt to nonlinear relations and trends present in the data and learn them during the model training process. Since ML models learn from data, the same model structure could be applied to a wide variety of problems. More information about learning from data is provided in the next section.

- Adapting to new data: As new data become available, ML models can adapt and change their parameters to capture new patterns and trends in the data. In traditional models, the user selects certain salient features (e.g., data attributes) manually. On the other hand, modern ML models [e.g., convolutional NNs (CNNs) and DL models] learn the most useful features automatically during the training process. This provides a significant advantage over traditional models. As the input data vary over time, these features may vary as well. ML models can adapt to new data by capturing such new features and optimizing their parameters in a (re)training process. Through iterative retraining, ML models can maintain their relevance and predictive accuracy over time as the data changes.

- New insights and solutions: Another important benefit of ML models is their capacity to uncover new insights and solutions that might not be easily discovered by experts. ML models are particularly adept at searching through complex data and identifying patterns and correlations that might not be obvious with traditional analysis. Traditional models often involve prior hypotheses and have predefined structures, which may limit their adaptation or learning from the data. The capabilities of ML models have been demonstrated in various diverse fields.

- In gaming, ML algorithms (e.g., AlphaGo) have devised strategies and moves that were previously unexplored by human players, while in drug discovery, ML models have identified previously unknown compounds with therapeutic potential. In the transportation field, ML models developed for self-driving vehicles can recognize objects, make real-time decisions, and navigate complex environments without the need to explicitly preprogram all possible scenarios.

- Ability to learn from high-dimensional complex data: ML models are effective in learning to make accurate predictions even if the data are complex and high-dimensional, which means the data have many input features. They employ iterative processes and algorithms that can detect patterns, make decisions, and improve over time. ML models extract the most informative features and reduce the complexity of the raw data using different types of techniques (e.g., Principal Component Analysis [PCA] or autoencoders). The best model parameters are found through optimization algorithms (e.g., gradient descent) that can handle high-dimensional search. ML models are found to be effective in handling large and diverse sets of video/image, computer code, point cloud, text, speech, geospatial, and other kinds of data.

Learning from Data

A fundamental aspect of ML is learning from data without the need to specify explicitly what and how data features should be used by the algorithm. For example, deep NN can capture complexities in the input data and recognize useful patterns if trained with sufficient data. In general, more data translates to more accurate predictions and robust models. In the transportation field, vast amounts of data with complex relationships have become increasingly available in recent years because of the proliferation of sensors and automatic data collection systems (e.g., connected vehicles data, condition monitoring sensors). There is a large body of academic studies on how ML could provide value in processing and leveraging such data. For more information, see Chapter 1 of NCHRP Web-Only Document 404: Implementing and Leveraging Machine Learning at State Departments of Transportation (Cetin et al. 2024), a conduct of research report that documents the development of the guide and the entire research report, available on the National Academies Press website (nap.nationalacademies.org) by searching for NCHRP Research Report 1122: Implementing Machine Learning at State Departments of Transportation: A Guide.

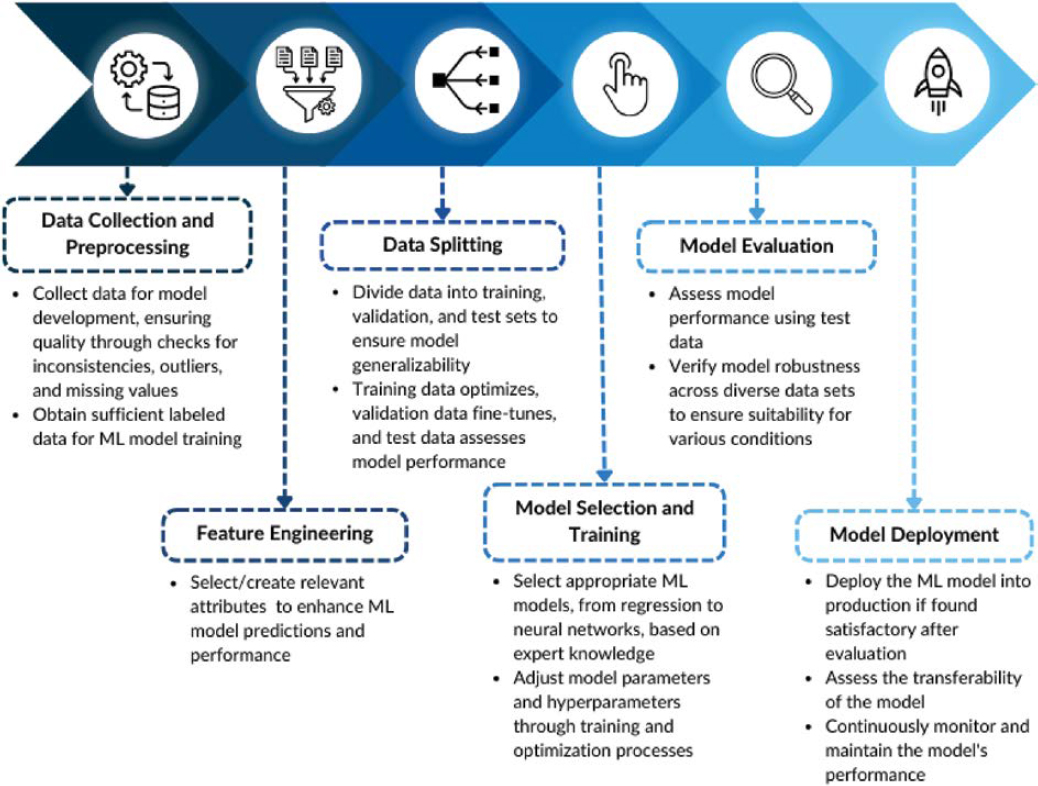

Various types of learning paradigms have been proposed based on data availability and the intended outcome of the ML model. Depending on the use case, the learning structures include supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning. These learning types are distinguished based on the relationship between the input and output and the way the ML model interacts with the training data. If both input and output (also referred to as “labels”) are used to train the ML model, the structure is referred to as supervised learning, in which case the ML model learns the relationship between the input and given output. The algorithm “learns” by going through examples in the dataset and by trying to find patterns or rules that connect the input data to their corresponding output (or labels). After the algorithm learns, it can take a new, unseen piece of input data (e.g., a new image of a vehicle) and predict the output (e.g., correctly identify the class of vehicle in the image). In the model training process, the model adjusts its internal parameters to improve its predictions based on the examples it has seen. After training, the model is tested with a new set of data it has not seen before, a process called model validation. If the validation results are satisfactory (e.g., accuracy levels meet the expectations) the model could then be considered for implementation. Supervised learning is the predominant type of learning in most ML applications.

If the input data do not have an associated output, unsupervised ML models can be used to extract possible patterns and cluster the input data based on similarities between the attributes of the different data points. For example, speed data coming from connected vehicles (CVs) may

contain multiple clusters because of variations in vehicle types (e.g., trucks versus passenger cars) or traffic conditions (e.g., congested versus uncongested). If the conditions under which the CV data are collected are unknown in this example (e.g., vehicle types are unknown), and clustering of the data is desired, unsupervised ML models could be employed to identify such patterns in the data. These models analyze the observations and cluster data points exhibiting similar characteristics in the same group.

Reinforcement learning (RL) is a different learning process, in which the machine (or agent) learns from interacting with an environment and the consequences of its actions (Figure 4). For example, through a trial-and-error process, an RL algorithm can learn how to best time a traffic signal if provided with a simulation environment and a goal. The goal (more technically the reward function) can simply be minimizing total delays. In this form of learning, the purpose is to find the best policy that will optimize a reward function. The policy in this context would be determining the signal timing parameters (actions) for a given set of traffic volumes (system states). RL methods are suitable for determining the optimal solutions to sequential decision problems. While there are many academic articles on potential RL applications in transportation (see Chapter 1 of Cetin et al. 2024), examples of practical applications of RL methods at state DOTs are hard to find.

Trends in Machine Learning

The ML landscape is evolving rapidly and is driven by advancements in algorithms, computational power, and the availability of large datasets. Recently, applications built on top of large language models (LLMs), such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini, among many others, have gained significant attention and made it possible to perform many tasks without the need for coding expertise. These publicly available models operate with billions of parameters and are trained on vast amounts of data. This makes it possible to perform high accuracy on an extensive range of language-related tasks. These generative AI models are becoming more powerful for numerous applications, including conversational interactions and generating text, video, and computer code. These models could support various agency operations, including summarizing and analyzing large documents and helping staff with coding or creating Excel formulas. However, they have also raised many ethical concerns, such as those regarding ownership of the created content and compliance with copyright laws. Despite their impressive capabilities, it is important to note that these models are not error-proof and can still generate inaccurate results and information. The following callout box shows the response from ChatGPT to a question on the top three strengths and weaknesses of ML.

As the ML landscape evolves, the implementation of ML to solve real-world transportation problems will evolve as well. For example, the level of effort needed for model training may diminish in the future as more robust multipurpose pre-trained models become widely available or

![]() Response 1

Response 1

Certainly, here’s a more concise summary:

Strengths:

- Pattern Recognition: Efficient at identifying patterns in data.

- Automation: Automates complex, repetitive tasks.

- Adaptability: Improves with more data over time.

Weaknesses:

- Data Dependency: Requires large, quality datasets.

- Lack of Explainability: Often operates as a “black box.”

- Resource Intensive: Needs significant computational and expert resources.

the norm. Important trends will likely impact how ML solutions are procured and deployed by transportation agencies in the future. Some of these include the following:

- Automated machine learning (AutoML) and machine learning as a service (MLaaS): AutoML and MLaaS offerings are making ML more accessible to non-experts. These are expected to increase the usage of ML since the need for expertise and a skilled workforce will be minimized.

- Algorithmic Innovations: New ML algorithms and architectures, particularly in deep learning, are being developed at a rapid rate. Innovations like attention mechanisms, transformers, and generative adversarial networks have opened new possibilities in areas such as natural language processing (NLP) and synthetic data generation. These innovations help create new models (e.g., large language models) that can solve a broad range of problems.

- Data Availability: ML models thrive on large datasets, and the increasing availability of big data has been a significant driver of ML progress. As more transportation data become available and more ML models are developed and tested, such models are expected to become more widely available and accessible to agencies.

- Cloud Computing: Deploying ML models on the cloud platforms allows access to the necessary computational resources and alleviates the need to invest in expensive infrastructure.

There are numerous resources on ML, including online courses, tutorials, sample codes and notebooks, research papers, books, and so forth. The AI Primer published by the Transportation Research Board Committee on Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Computing could be a good starting point for an overview of ML; see https://sites.google.com/view/trbaed50/resources/primer?authuser=0.

Interpretability of ML Models

It should be noted that some ML models are criticized as being “black boxes” because of the lack of transparency in how they generate their outputs. For applications where model explainability and/or interpretability are critical (e.g., because of regulatory compliance), complex ML models may not be suitable. Explainability and interpretability are closely related concepts. Interpretability is about the clarity of a model or the degree to which a human can understand

the cause of a decision and the inner workings of the model. A decision tree is considered interpretable because its decision-making process is clear and can be followed step-by-step. On the other hand, explainability is focused on explaining the decisions made by complex ML models (e.g., deep NN). Various methods are developed to make the ML model’s outputs explainable, even if the inner workings of the model are complex and opaque. In other words, other models are built to explain complex ML models. For example, through visualizations of what the model is focusing on when making decisions, or post-hoc explanations for specific decisions, the user may be able to understand the links between inputs and outputs produced by the ML model. The field of explainable artificial intelligence deals with creating methods to explain and reveal such links.

Generally, there is a trade-off between a model’s performance (e.g., its prediction accuracy) and the degree of explainability or interpretability – high-performing models tend to be more complex and, hence, have lower interpretability. Figure 5 shows this trade-off and lists sample ML models with different levels of complexity and interpretability. When considering an ML application in transportation, the need for model transparency needs to be assessed, and ML models meeting these needs should be selected. For applications where explainability is not critical but accuracy is, such as detecting pavement cracks from image data, complex models such as deep NN would be appropriate.

Step 1: Identify Use Cases

ML models are useful for performing various types of tasks. With the proliferation of deep learning methods and the availability of large datasets, ML models have been proven to be very effective in key image processing tasks including object detection (identifying objects within images), classification (e.g., categorizing images into classes), and semantic segmentation (labeling every pixel in an image according to its category). Numerous ML/DL applications have been built over the last decade across all major sectors addressing various needs and leading to transformative impacts. Such examples include drug discovery and medical image analysis, fraud detection in financial data and credit scoring, driving assistance systems in autonomous vehicles, content creation tools for arts and entertainment sectors, climate modeling, and more.

According to the survey conducted as part of the NCHRP 23-16 project, at least one respondent from 15 of the 29 states represented in the survey indicated that their agency had ML applications currently deployed and/or being developed. These agencies have implemented ML solutions for various applications, with transportation systems management and operations (TSMO) and asset management being the most common. The NCHRP 23-16 conduct of research report also presents a summary of the ML state of the practice that was based on nearly 70 identified ML-related projects involving agencies (see Chapter 1 of Cetin et al. 2024). Based on this summary, ML solutions have been explored and are being developed for several areas, such as

- Vehicle automation,

- Safety applications and driver behavior,

- Planning applications,

- TSMO applications [work zone management, traffic incident management (TIM), road weather management, traffic estimation and prediction for decision support, vulnerable road user detection, intelligent traffic signals, and other miscellaneous operations],

- Asset management,

- Commercial vehicle and freight operations,

- Transit operations, and

- Traveler information and accessibility.

In addition to the application areas listed above, state DOTs are beginning to explore the possibilities of LLMs to support various functions, including their business operations. For example, the Massachusetts DOT, in collaboration with the University of Massachusetts, is training a custom LLM to generate workforce development content based on their contracting documents and design guidelines (Newberry 2024). Agencies deploying ML for these different application areas are starting to report their findings and document the benefits accrued. The Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) benefits database developed and maintained by the Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office (ITS JPO) of the U.S. DOT includes several projects with an ML/AI component. The following two samples are included here to highlight some of the reported benefits and more details can be found through the ITS Deployment Evaluation of the ITS JPO.

- “AI-based Roadway Safety and Work Zone Detection Technology in Nevada Uncovered 20% More Crashes than Previously Reported and Reduced Crash Response Times by Nine to

- Ten Minutes on Average” (ITS Deployment Evaluation 2022a). The Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada, together with the Nevada Highway Patrol and Nevada DOT, launched an AI-based platform in collaboration with a technology company in 2018 that allowed crash locations to be reported in real time. The AI platform reduced emergency response time during traffic crashes by eliminating the time required to dial for help.

- “Video-Based Advanced Analytics is Detailed Enough to Identify Near-Crashes, Classify Road User Types, and Detect Speeding Infractions and Lane Violations” (ITS Deployment Evaluation 2022c). The city of Bellevue, WA used AI algorithms to process traffic camera footage to monitor traffic and road users and potential conflicts. They found that people riding bicycles were 10 times more likely to be involved in a conflict than motorists.

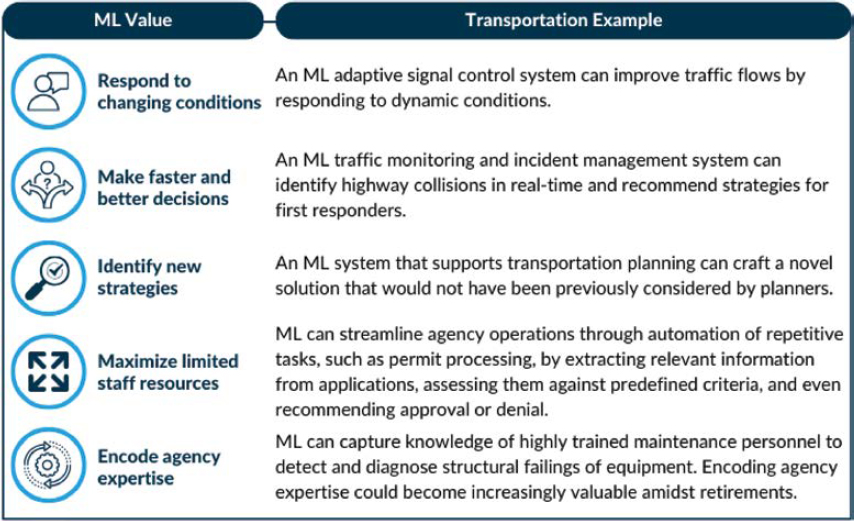

The widespread use of sensors in transportation continues to generate large amounts of data. State DOTs are exploring effective ways to process and extract value from such data. ML tools and methods are anticipated to play an increasingly more important role in supporting DOT operations as ML solutions become more mature over the years. ML may offer effective solutions for processing large data for various applications including system state estimation, prediction/forecasting, condition monitoring, control and optimization, customer relations, and others. These capabilities can fundamentally support all DOT functions (e.g., traffic operations, safety, planning, public transportation, construction, and asset management).

Most ML-related solutions typically start as research ideas/projects or academic studies which are subsequently published in scientific journals and conference proceedings. As part of the literature review for the NCHRP 23-16 project, numerous papers in the Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board and other journals were reviewed and synthesized. In Chapter 1 of NCHRP Web-Only Document 404: Implementing and Leveraging Machine Learning at State Departments of Transportation, Cetin et al. present a review of the transportation literature on ML methods and the types of application areas these methods have been applied (Cetin et al. 2024). Based on the published literature, applications of ML in traffic operations stand out as one of the most popular areas, with planning and infrastructure/asset management closely trailing behind. Some of the most popular problems to which ML tools have been applied include speed, travel time and traffic flow prediction and estimation, traffic signal optimization, incident detection, vehicle detection, origin-destination demand estimation, dynamic traffic assignment, parking space management, crash severity and frequency analysis, driver behavior analysis, bus arrival estimation, ridesharing, pavement condition assessment, and emissions monitoring. Table 1 summarizes example application areas and specific problems (in no particular order) being addressed with ML methods based on the synthesized literature. This table shows the breadth of applications and different types of problems for which researchers have developed ML solutions. The literature on ML applications in transportation has been continuing to grow rapidly as illustrated in Figure 1 in Chapter 1 of the NCHRP 23-16 conduct of research report (Cetin et al. 2024).

The advanced ML methods published in the literature may eventually be deployed in the field and some have been already implemented by state DOTs. For example, the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development is moving away from using traditional methods for volume estimation, replacing them with ML-based models. Different agencies have taken different routes based on their specific needs and capabilities. Many DOTs have partnered with universities to explore options for ML implementation. For instance, Iowa DOT partnered with Iowa State University to develop an incident detection system called Traffic Incident Management Enabled by Large-data Innovations. Their system is focused on using already existing surveillance cameras in rural areas where it may take a while for highway patrol to receive notifications. Other agencies have preferred outsourcing these applications, using proprietary software subscription services either as supplements to traditional methods or to replace them. For example, the Nevada and

Table 1. Example types of problems being solved by ML methods for different application areas based on the literature review.

| Application Area | Problems Being Addressed or Solved by ML Methods |

|---|---|

| Operations | Speed, travel time, and traffic flow prediction |

| Traffic signal timing design and optimization | |

| Vehicle classification | |

| Incident detection | |

| Variable speed limit and ramp metering control | |

| Asset management and infrastructure | Pavement crack detection |

| Defect detection for railway tracks | |

| Roadway asset inventory | |

| Preventive maintenance decisions and scheduling | |

| Structural health monitoring | |

| Traffic sign and pavement marking detection | |

| Safety | Crash classification by severity |

| Estimate crash frequency | |

| Classification of driver behavior (e.g., distracted, fatigue) | |

| Planning | Travel mode prediction |

| Estimate origin-destination demand | |

| Dynamic traffic assignment | |

| Estimate car ownership and carpooling behavior | |

| Parking space management | |

| Public transit | Ridership demand prediction |

| Vehicle scheduling and routing decisions | |

| Bus arrival time estimation | |

| Transit signal priority design | |

| Rail maintenance and inspection | |

| Pedestrians and bicycles | Tracking and detecting pedestrians and bicycles |

| Bike sharing demand and usage prediction | |

| Freight | Optimization of freight terminal operations |

| Truck volumes and freight flow estimation | |

| Freight delivery and scheduling | |

| Automated vehicles | Object detection and tracking |

| Motion and route planning | |

| Scene segmentation | |

| Traffic sign and light recognition | |

| Environment | Emission monitoring and estimation |

| Wildlife monitoring (e.g., near highway rights-of-way) | |

| Cybersecurity | Intrusion and anomaly detection |

Florida DOTs have used third-party software for better incident detection and have already seen considerable reductions in secondary crashes (∼%17). Roadway weather management and work zone management are other areas in which many agencies have already implemented new ML-based solutions. As part of the NCHRP 23-16 project, five case studies were conducted with state DOTs to understand their approach to ML solutions. Table 2 shows the list of five DOTs interviewed and the types of applications for which they used ML methods and technologies. The next section presents some guidelines on whether ML solutions would be a viable approach to the problem being considered.

Based on the information presented above, it should be clear that ML methods could be applied to a wide range of problems and challenges DOTs might be facing. State DOTs interested in identifying candidate ML use cases could benefit from the experience of other DOTs. The ITS JPO’s ITS benefits database could be a good resource to search for existing or completed ML deployments. The next section presents some guidelines on whether ML solutions would be a viable approach to the problem being considered.

Table 2. Agencies interviewed for the case studies.

| Agency | Primary Application Area | Needs Addressed | ML Methods | Input Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) | Asset management | Litter detection | Deep learning | Video |

| Delaware DOT (DelDOT) | TSMO | Incident detection Traffic flow prediction Proactive traffic management |

Deep learning | Vehicle detectors Video Probe data |

| Iowa DOT | Safety | Highway performance monitoring Incident detection |

Deep learning | Vehicle detectors Video |

| Missouri DOT | TSMO | Incident detection Real-time identification of high crash risk locations Prediction of road conditions including winter weather events |

Deep learning Unsupervised learning Boosting |

Vehicle detectors Video Probe data Incident data |

| Nebraska DOT | Asset Management | Guardrail detection and classification Marked pedestrian crossing detection |

Deep learning | Video |

Decision Gate #1

ML solutions are becoming an integral part of DOT operations and planning, driven by the maturation of ML/AI methodologies. While certain applications, such as license plate recognition from image data, are already mature and have become almost industry standards, others, like traffic signal control using reinforcement learning or incident detection from sensor data, remain in nascent stages. Nevertheless, before proceeding with a decision to consider ML as a potential solution for a given application, one needs to consider whether ML is a viable option or the right approach to the problem. In addition to the commonly used performance metrics (e.g., return on investment, benefit/cost ratio, regulatory compliance) that apply to any other deployments, there are additional criteria that state DOTs might consider in pursuing ML solutions. Assuming the decision-maker has a basic level of familiarity with ML, this initial assessment could be accomplished by considering the following elements:

- Potential reasons for considering ML as a viable solution include the following:

- – ML technology for this problem is already mature (e.g., multiple vendors offer this technology, and multiple DOTs are already deploying it).

- – The nature of the problem aligns well with typical ML applications as it pertains to classification, pattern recognition, image processing, predictive analytics, real-time decision-making, discovering relationships, and so forth.

- – There is a need for automation, improved efficiency/safety, scalable solutions, and extraction of new information or insights from data.

- – The traditional statistical or physics-based approaches are not sufficient in producing satisfactory results.

- – There are sufficient data for model training, validation, and testing.

- – There are established (open-source or otherwise) transferable pre-trained models that are proven to be effective for the problem at hand.

- – The agency has the required resources (e.g., financial, technical knowledge, and computing) needed to support the procurement or development of ML applications.

- Potential reasons for not considering ML for a given problem include the following:

- – The problem is not complex, and there are already established effective traditional solutions.

- – There is no or very limited use of ML for solving this problem, and the agency is not interested in developing new models.

- – Sufficient data or computational resources are not available to train or validate ML models.

- – The solution requires an interpretable model where an explanation is needed as to why a given outcome is generated from the input data.

- – The agency does not have the resources (e.g., financial, technical knowledge, or computing) needed to support the procurement or development of ML applications.

- – The available data are biased or unrepresentative, and using ML models could perpetuate or exacerbate these biases, leading to unfair or unethical outcomes.

- – There are rules and regulations prohibiting the use of ML for the application being considered.

The specific criteria for procuring or deciding to pursue ML solutions will differ significantly between well-established solutions and those still under exploration. For instance, mature methods and pre-trained models might not necessitate additional model training since they are

already calibrated for various field conditions. In contrast, emerging ML models and applications often demand extensive model training. This, in turn, requires large datasets, computational resources, and expertise in ML techniques. Thus, state DOTs must evaluate their capacity to provide the resources needed to develop effective and reliable ML solutions.

To determine if a state DOT should adopt ML solutions, an initial assessment should focus on the maturity of the intended application and any existing implementations or tests by other agencies. Generally, an ML application is considered mature if there are multiple vendors or providers of the desired solution. Such solutions might be offered by transportation consulting companies as well as by those outside the traditional transportation field, such as technology firms or startups. If the application being sought is well-established and mature and no model training is anticipated, the decision to proceed will depend on the commonly used criteria for technology procurement. While the exact criteria might vary from application to application, there are general criteria that many state DOTs consider including benefit-cost ratios, reliability, interoperability, scalability, security, compliance, usability, longevity, environmental considerations, vendor’s reputation and track record, training requirements, support and maintenance, customizability, and contractual terms. In addition to these, the accuracy of the ML solution needs to be evaluated to ensure the agency’s requirements are met. Furthermore, any required computational resources need to be identified.

If the state DOT is considering an ML solution that will require model training and development, there are additional criteria to be considered, including the following:

- Availability of data: Are there enough quality data available for model training and testing? ML models often require labeled data for model development. If sufficient data are not available, a plan for acquiring such data must be made and the resources needed for gathering and processing the data should be identified.

- Trained workforce: Does the agency have sufficient expertise in ML to evaluate, develop, and adopt ML methods? The agency needs to ensure that there is enough expertise and trained personnel to either develop the solution in-house or work with a consultant.

- Institutional policies: Data privacy, resources available for investment in research and model development, the amount of risk the agency is willing to take to achieve its objectives, and bias in ML models are among some of the considerations that need to be addressed.

- State of the practice and technology transfer: Prior experience from other states/agencies implementing ML is an important consideration. If other agencies have developed similar applications and had positive experiences, there might be opportunities for knowledge transfer. Such experiences can help in reducing the model development time and cost.

- Computational resources: Various computational resources are needed for ML applications, including powerful hardware, such as central processing units (CPUs), graphics processing units (GPUs), sufficient RAM, and ample storage, optimized for rapid data processing and storage. High-speed Internet and intranet are essential for data transfers, while cloud services offer scalability for intensive tasks.

- Pilot versus full-scale deployment: The scope of the application can influence the factors to be considered. For example, full-scale deployment requires more in-depth analysis and planning to ensure that a broader range of conditions are addressed effectively by the ML solution. In addition, a larger number of stakeholders might be involved when deploying full-scale solutions. Pilot studies are typically shorter in duration and are meant to test the validity and utility of the ML solution in a constrained environment. Pilot studies involve less risk in case of unsatisfactory model performance whereas the risk of failure is higher with full-scale applications, as the failure may result in significant disruptions or wasted resources. In addition, life cycle and maintenance costs need to be considered with full-scale deployments.

Based on an initial assessment of the considerations and criteria listed above, the agency can decide whether to pursue ML for their given problem. Furthermore, the deployment of ML solutions must carefully navigate through a complex terrain of legal and regulatory frameworks at local, state, and federal levels. These regulations, which govern different aspects of AI/ML, such as data privacy, ethical usage, transparency, and application-specific restrictions, play a critical role in shaping the project’s scope, design, and implementation strategies. The subsequent steps in this guide provide additional information and a more in-depth evaluation of the requirements and other considerations for ML applications in transportation.

Step 2: Assess Gaps

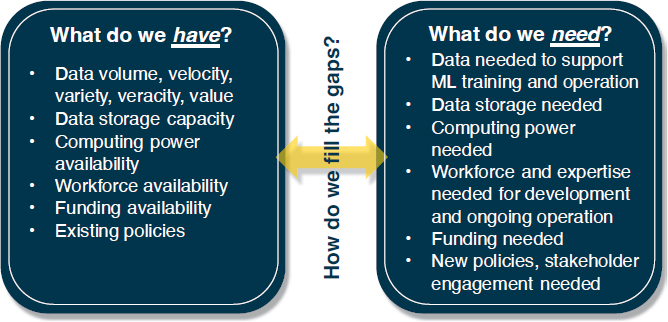

Once it is decided that ML is a desirable approach for the problem at hand, the agency team will want to conduct a more detailed inventory of their available resources and skills to support an ML pilot project. The team must estimate the resources that will be needed to execute the project to identify potential gaps. While traditional transportation projects at state DOTs have many physical infrastructure considerations (e.g., making roadway infrastructure improvements, retiming signals, and deploying proven safety countermeasures), ML projects bring new digital infrastructure considerations, including specific data, storage, and computing considerations. Additionally, ML projects may bring new workforce, funding, and other considerations (e.g., privacy). See Figure 6.

Table 3 summarizes key questions the agency may want to consider before planning its specific pilot project. Essentially, in this step, the agency may want to ask the following:

- What resources do we have to support an ML pilot project?

- What resources do we need to support an ML pilot project?

Data

The team may want to start by defining the data, including identifying what data elements are available and what data elements are needed for the ML application. Just because a data source is available does not mean it will be valuable for the ML application. Often, data transformations are necessary to make certain elements potentially useful for the ML application. But transformations alone may not be sufficient. New data may need to be added to the mix for the ML application to be effective. For example, features like lane and minute-level traffic data feeds would typically not be necessary for legacy traffic management center (TMC) operations. However, as illustrated by DelDOT in their case study, these data become very important as input to ML algorithms for predicting traffic conditions at a higher level of granularity (see Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024).

Table 3. Key questions to assess availability and gaps to support ML project.

| Resource Availability | Key Questions to Assess | Key Questions to Assess Gaps |

|---|---|---|

| Data | What sources of data do we have already? For each available data source, what is its volume, velocity, variety, veracity, and value? |

How much data are likely required for the use case? Do we need additional sources of data? How frequently should we collect data to capture time-dependent changes in the system? |

| Storage | How are our data currently stored? How much available storage do we have? |

For the size of data required for the use case, how much storage might we need? |

| Computing | What computing resources do we currently have? | What type and how much computing power might we need for ML model training? For ML model operation? If using cloud computing, which provider, how many resources, and what services should we acquire? Central or edge computing? How frequently do we need to retrain the ML model? |

| Workforce | What data science expertise and experience do we have within our workforce and what is their availability? | Do we need additional expertise in development or deployment, and with whom can we work that has that expertise? |

| Funding | What sources of funding do we have to support our ML pilot? | Are there additional funding sources we should seek out? |

| Other | What existing policies might impact our ML pilot? Are there any concerns regarding collecting and storing data containingpersonally identifiable information (PII) for ML training and/or deployment? What resources do we have to support long-term maintenance once the system is deployed? |

To be compliant with existing policies, do we need to reassess our data collection strategy? Conduct additional stakeholder outreach? Expand policies or security for sensitive data? What resources might we need to sustain the ML application long-term (e.g., funding, staff, software, data inputs, etc.)? |

Modern ML algorithms require training on massive amounts of data to make inferences or predictions. In recent years, artificial NN and deep learning frameworks have surpassed other types of algorithms in complex tasks such as machine vision and object detection. These algorithms require huge amounts of data to sufficiently train the many parameters that comprise these models. That being said, a trend has been to use pre-trained models [e.g., the “you only look once” (YOLO) algorithm for object detection or LLMs for NLP and natural language understanding tasks] to train a more specialized model. This approach may not require a huge amount of additional data, depending on the use case, but it does require specific, representative data.

Data and their requirements are sometimes characterized by the “5 V’s of Big Data.” Table 4 lists these five characteristics that define data and expands on their definition.

The Five V’s provide a useful framework that DOTs can consider when assessing their data capabilities for ML. Notably, the costs and level of effort associated with realizing the benefits of new data sources are not minor. Even in cases where data collection is cheap, cleaning, curating, standardizing, integrating, and implementing collected data can be expensive and challenging (Lane et al. 2021). In the end, more data may not necessarily be more valuable for an ML application.

Table 4. Five “V’s” of data.

| Data Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Volume | Refers to the quantity of generated and stored data. Because of the proliferation of sensors collecting data, data being logged by users of cellular and Internet services, and the rapid increase in Internet of Things (IoT) devices, terabytes and even petabytes of data are being created. |

| Velocity | Refers to the speed at which data is accumulated. Data are being streamed at higher rates by more devices because of improvements in connectivity such as 5G mobile networks and IoT devices. |

| Variety | Refers to the different types and natures of the data. Data can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured and come in formats as diverse as sensor data, data tables, raw images, text, videos, or audio files. |

| Veracity | Refers to the assumed quality, completeness, consistency, representativeness, and accuracy of data. |

| Value | Refers to the usefulness of the data in the context of solving understood problems and making better decisions. The value of data is context-dependent with respect to the problem being solved using ML applications. |

Volume

Acquiring and managing training data in sufficient volume to train deep learning algorithms is often among the most arduous and expensive aspects of machine learning pipelines. Modern transportation agencies collect troves of high-resolution data from many sources including traffic detectors, images and video from closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras, weather stations, vehicle probes, crowdsourced traveler information, and more.

Although there is no formula for the volume of data needed to train algorithms for a given task, practitioners can reason using heuristics. In general, the more complex the task and the more complex the model, the more data will be required to result in desired performance (Brownlee 2019). A simple rule of thumb for computer vision tasks that conduct image classification using deep learning is to include 1,000 images per class, although this number can decrease when using pre-trained models (Mitsa 2019). A learning curve, which plots the training dataset size on the x-axis and an evaluation metric on the y-axis, can be used to determine how additional training data are impacting performance. If the result converges, it may be evidence that more data will not result in greater performance using the same model type.

Insights from Nebraska DOT Case Study on Data Volume

(Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024)

Data management often becomes unwieldy when incorporating such large quantities of data. For example, the Nebraska DOT’s team processed 2.5 million images from its 2019 roadway network profiling to classify guardrails and marked pedestrian crossings. The large size of these video logs proved to be a challenge in transferring data to their vendor providing ML services. In the end, the Nebraska DOT team downloaded the large files to a hard drive and shipped the hard drive to the vendor for processing.

Velocity

Agencies are seeing the implementation of more data collection infrastructures that transfer data in near real-time. In contrast to offline analyses, processing data in real-time through an

ML model poses additional challenges, especially when the data volume is high. These very high data velocity sources are often a challenge to manage and incur significant costs. The costs of data transfer can sometimes outstrip the costs of data storage. These costs scale with the volume and frequency with which data are transferred. Extract-transform-load procedures are necessary, as raw data must be aggregated, cleaned, transformed, linked, standardized, and put through other pre-processing procedures to be fruitfully used as input features to ML models. These transformations require computing resources, and these computing resources scale with the volume and velocity of input data.

Variety

Today, data comes in more forms than ever. Structured data are traditional data that are typically organized into tables and can be stored in a relational database. Semi-structured data are data that conform to some known format or protocol but otherwise are not connected, such as JSON files, sensor data, or comma-separated values files. Unstructured data are unorganized and do not conform to typical data organization schemas, such as video, images, emails, or audio files (Gutta 2020).

The wide variety of data sources that agencies are expected to manage presents complications in data fusion. It may not be immediately clear how to incorporate different forms of data into the same ML pipeline. The data may differ in temporal (e.g., minutes versus hours) or spatial resolutions (e.g., zip codes versus Census tracts). In other cases, different data sources might provide redundant or conflicting information.

Insights from Delaware DOT and Missouri DOT Case Studies on Data Variety

(Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024)

To support their Artificial Intelligence Integrated Transportation Management System (AI-ITMS), Delaware DOT linked many different existing and new data sources of various types, including traffic, weather, travel restriction, CCTV, and probe vehicle data. For example, they made enhancements to data collection capabilities such as instrumenting data loggers to track vehicle dynamics to function as probe vehicle data.

In the St. Louis County AI deployment, Missouri DOT found issues with different data sources providing alerts for the same traffic incidents. The system originally did not have a way to recognize these redundant events and filter them, therefore, double counting and presenting them as separate incidents.

Veracity

The quality, integrity, credibility, completeness, consistency, and accuracy of data must never be taken for granted. Agencies should have quality control processes for obtaining and validating high-quality data to build systems with consistent, predictable results (Vasudevan et al. 2022b). Errors may stem from failures of physical infrastructure. Sensors may go offline unexpectedly, be calibrated poorly, or encounter communication or mechanical issues that result in incomplete or altered data. Even if the sensors are all working, they may be distributed unequally across an area where an ML system will be applied, resulting in biased decision-making. Data may be unintentionally omitted, duplicated, incorrect, incomplete, or inaccurate. For example, data fusion and linkage could result in unintended duplicates that, if fed to an ML model during training, could bias the results.

Early on in their deployment, DelDOT was made aware of data quality issues impacting the robustness and accuracy of their ML models. They employed several techniques to mitigate this issue. They decided to train their algorithms on data that may have been missing, corrupted, or otherwise polluted to ensure that they were sufficiently robust to detect and mitigate communication failures.

Another issue is the lack of labeled data to serve as ground truth. Most data created and collected are unlabeled and unstructured data (e.g., audio, image, video, and unstructured text files). Many ML tasks are supervised tasks (i.e., involve matching features to labels). Therefore, before training algorithms, agencies may have to manually or semi-manually label their data. The level of effort needed for data labeling depends on the complexity of the task. For example, if specific objects (e.g., traffic signs or guardrails) are to be identified from a random image by an ML model (e.g., a semantic segmentation model), the specific pixels making up the objects of interest need to be manually labeled with bounding boxes so that the ML can be trained and tested. This could be very labor intensive. On the other hand, some datasets may already contain the label(s). For example, if the agency is planning to build an ML model for predicting travel times (e.g., as a function of historic travel times, and spatiotemporal attributes) and has access to probe vehicle data, such data already contain the label, and the effort required for data labeling will be minimal. Additionally, pre-trained ML models are likely to already know labels for certain classes since they were previously labeled and trained. For example, Figure 7 shows sample output from YOLOv8, a popular object detection algorithm, which has already been trained to recognize certain classes of objects as shown by the bounding boxes and labels in the image.

Value

Arguably the most important characteristic of data, value is highly context-dependent. Just because an organization or vendor has access to data does not make it valuable. The value of data is reliant on it being an input to models that help organizations solve business needs. If the data create models with high accuracy, but those models are unable to positively impact business needs, then the data are not valuable. One such issue might be the timeliness of data. For instance, suppose that an agency is trying to build ML models to help them predict and respond to traffic incidents. They found that their model has 100% accuracy in classifying incidents, however,

Insights from Delaware DOT Case Study on Data Value

(Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024)

Delaware DOT found that their models required higher resolution data than their TMCs typically worked with. Although they had traffic detection sensors and systems already in place, they were not proving to be sufficiently powerful to make valuable predictions for operators. Therefore, DelDOT increased the resolution of their sensors to provide lane-by-lane traffic information, which provided real value to their operations.

it was trained on and requires data up to 1 hour after the incident has taken place. The TMC needs to be made aware of incidents much quicker than this to respond, and therefore the model provides them no value. Another issue may be data lacking labels to serve as ground truth in training an ML model. Unlabeled data may not be useful for many mainstream applications. For example, raw sensor data (e.g., from cameras, LiDAR, or radar) are unlikely to provide much value when training an ML model to classify road users unless it knows which road user types are of interest and where they are in the training data.

Table 5 summarizes considerations for filling data gaps for each of the five “V’s.”

Table 5. Considerations to fill data gaps.

| Considerations to Fill Data Gaps |

|---|

|

Data Storage

In addition to assessing data availability and gaps, the team will need to assess the data storage capacity, type, and cybersecurity considerations needed to support ML training and, potentially, operation.

Data Storage Capacity

Being a data-driven approach, ML requires a non-trivial quantity of training data to learn underlying patterns. This large quantity of data must be stored and readily accessible to train ML models. Increasingly, agencies have access to and are using large data sources, such as images and videos from cameras, raw text from social media feeds or incident reports, audio from dispatches, and so forth. Not only are these data sources much larger than traditional tabular data sources that dominated data analytics in the past, they are also unstructured, meaning they do not follow a neat, predefined schema. Both the size and the nature of these data sources bring important considerations for data storage. For example, video feeds from a few dozen city cameras may easily impact the capacity of existing data servers housed in the TMCs (Vasudevan et al. 2022b). Doing a “back-of-the-envelope” calculation can provide a rough order of magnitude (ROM) estimate of the amount of data storage needed for training a vision-based ML model (see callout box on “Example Hypothetical ROM estimate of Image Data Storage Capacity for ML Training”).

It can be a tricky balance to gather and store a sufficiently large, representative sample of training images for each class while keeping the overall data size in check. Data size not only directly determines the data storage capacity needed to support ML but also determines the type of data storage to consider.

Example Hypothetical ROM Estimate of Image Data Storage Capacity for ML Training

A common rule of thumb is to have 1,000 images per class when training a DL computer vision model. Using the CostarHD OCTIMA 3430HD Series CCTV camera for purposes of this hypothetical example with 3-megapixel image quality, one can calculate an ROM estimate of the quantity of data needed. 3 megapixels equate to 3 million pixels. Each pixel requires 1 byte in memory for each of the three main color channels (i.e., RGB). Based on this calculation, each RGB color image from this CCTV camera is expected to require roughly 9 MB of storage. If the data scientist hopes to train the ML model to classify 10 different classes (e.g., 10 different vehicle types on the highway), using the 1,000-image per class rule of thumb, then 10,000 different images would be needed. At 9 MB each (without compression), these images would likely require roughly 90 GB of storage space. While 90 GB worth of image data could feasibly be stored on a single laptop (albeit it would take up a nontrivial amount of space), any more than that would likely require additional external storage (e.g., separate flash drive, server, or cloud storage). While the camera may generate 90 GB worth of images, it will do some compression (e.g., configurable H.265/H.264/MJPEG codec compression in this example) and internal post-processing (e.g., noise reduction) with some loss in image quality.

Data Storage Type

Many agencies use their existing data sources when possible (e.g., camera, weather, detector, etc.), whether they are using those data sources directly to develop ML in-house or sharing those data with their consultant or vendor teams to develop ML applications. Regardless of the development approach, the training data must be stored somewhere. A few of the main options are summarized as follows, including considerations for ML:

- Local Data Storage: While some of the agency’s existing agency data sources may already be stored locally (e.g., in files on a laptop, external hard drive, or USB flash drive), others may not be stored yet. For example, most agencies do not store video data from CCTV camera feeds, or if they do, they delete them after a certain amount of time (e.g., 24 hours). But to train an ML model on these data, they must be stored. Because of the unstructured format of video data and their large file size, it may be difficult to store them locally in a spreadsheet or traditional relational database [e.g., search query language (SQL)]. Because of potential capacity constraints of local server storage and the costs to purchase and manage additional servers, many agencies turn to cloud storage options to meet their needs.

- Database Storage: If multiple staff/teams from the agency intend to use and query the data frequently beyond just ML training, database storage might be a good option. This database could be hosted locally or in a cloud location. Unstructured data sources, such as videos, may need to be stored in non-relational databases or NoSQL (non-SQL) databases that allow for format flexibility. Common NoSQL databases include key-value databases (e.g., Redis), document stores (e.g., MongoDB), graph databases (e.g., Neo4j), and column-family stores (e.g., Cassandra), with each suited to different data types and use cases. However, if large unstructured data will only be stored and accessed a few times total without the need for complex or real-time queries, cloud storage may be the best option.

- Cloud Data Storage: Cloud storage is well suited for managing large data and can accommodate all sorts of data formats, including unstructured data. Many cloud providers—such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform—offer a variety of data storage options. Cloud storage costs depend on many factors, including the size of the data being stored, the frequency of data access and retrieval, and data transfers. For example,

Insights from Case Studies on Data Storage Type for ML

(Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024)

Delaware DOT decided to use an onsite solution (i.e., 10 local servers) for both data storage and computing in support of their AI-Integrated Transportation Management System, with redundant instances running on production and test servers.

Nebraska DOT relied on local data storage (i.e., a hard drive) to ship large video data files to their vendor for processing.

The interviewee from Caltrans mentioned that data storage costs for many gigabytes or terabytes of image data can be substantial, even if Google Cloud is used instead of dedicated in-house data servers.

The interviewee from Missouri DOT emphasized that additional data come with additional costs, not just for purchasing or collection, but also for processing, storage, and integration.

- transferring data in or out of the cloud, including uploads and downloads, could incur significant data transfer costs. Cloud storage providers tend to be “pay-as-you-go,” which can help in spreading out the costs as opposed to purchasing a new local server with large upfront costs. Often, vendors combine cloud storage with computing services in their cost packages. Examples and a further discussion are provided in this chapter’s section on “Computing.”

Cybersecurity

Each data storage type has cybersecurity considerations. While local storage allows for full customizability of how the data are stored (i.e., in what file or database structure) and what security mechanisms and permissions are used, this customizability generally comes with a higher level of effort to set up and maintain. If the agency lacks sufficient technical expertise to set up and maintain the local data storage, then it could lead to cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Additionally, if local data storage is used, the agency may want to back up the data somehow (e.g., make a copy on another local server) in case of hardware failure. With cloud data storage, some of these risks, such as data backups, are pushed to the storage provider. If cloud data storage is used, and especially if the data contain sensitive information, it is important to ensure the data are encrypted both when stored and when being transferred.

Beyond data storage, machine learning presents new potential cybersecurity vulnerabilities. There exist types of cybersecurity attacks specific to ML models that practitioners must be aware of. These attacks may be classified as security-based attacks or privacy-based attacks. Security-based attacks can cause the ML model to function in unintended ways, such as targeting training data for alteration or forcing models to output desired results. Privacy-based attacks refer to unintentional information leakage regarding data or the machine learning model (Rigaki and Garcia 2023).

Common forms of security-based issues are poisoning attacks and evasion attacks. In a poisoning attack, an adversary “poisons” the training data to alter the performance of the ML model. They do this by injecting data points into the training data to change tuned model parameters. These poison data may be highly noisy and solely degrade system accuracy, or they may be designed specifically to alter system performance in a specified way. For example, an attacker might label stop signs as yield signs, leading to a trained machine vision model that could not recognize stop signs. An evasion attack occurs during the testing of an ML model. The adversary intends to create an incorrect system perception. Following the stop sign example from earlier, some classification systems have been confused by putting reflective stickers on the sign. This would be an example of an evasion attack (Pitropakis et al. 2019).

There exist different types of privacy-based ML cybersecurity attacks that include membership inference, reconstruction, property inference, and model extraction. The most popular category of privacy attacks, membership inference, tries to determine whether a sample of input data was part of the training data. The goal is to retrieve information about the training data. This type of attack may be an issue in settings where potential adversaries have access to the model for querying. Reconstruction attacks attempt to recreate one or more training samples, possibly acquiring sensitive information. Property inference attacks extract properties of the overall dataset that were not explicitly encoded as labels or features. Finally, model extraction attacks attempt to partially or fully reconstruct a model (Rigaki and Garcia 2023).

Practitioners should be aware of ML cybersecurity best practices as they emerge. It is key to understand that when using ML, attackers do not necessarily need to gain access to the stored data to uncover sensitive information. If they have enough access to the model, the previously stated methods could create privacy leaks or lead to other cybersecurity concerns.

As AI services become more available and integrated into more people’s daily lives, there are new cybersecurity considerations to be aware of. For instance, professionals are now using LLM interfaces such as ChatGPT for various purposes like document summarization and brainstorming. However, it should be noted that users’ conversation history with ChatGPT may be collected, as well as information about the user’s account. This data may be used for training further models. Responsible practitioners should consider refraining from sharing sensitive information with ChatGPT and similar AI applications. As AI applications become more dispersed, these concerns may be less prevalent. For instance, if an organization has its own LLM models and applications that are hosted and maintained locally, concerns about data leakage are mitigated.

Computing

Computing is the “muscle” behind ML training and operation. The types and levels of computing resources needed for ML model training may be different from those needed for ML model operation, and both depend on the nature of the use case (e.g., the scale of data and the complexity of the task). Agencies seeking to simply implement a pre-trained ML model may not need intensive computing resources. On the other hand, agencies seeking to train a specialized ML model on large-scale unstructured data may need significant computing power.

Parallel, distributed, and/or clustered computing is often used to train large-scale ML models offline to augment processing power (Vasudevan et al. 2022b). For example, Nebraska DOT’s consultant team used virtual machines with NVIDIA GPUs, which parallelize processing, for convolutional neural network model training using about 1,500 labeled images containing guardrails and guardrail attenuators (see Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024). Once trained, edge computing, which is a distributed computing paradigm with data storage and computation close to the data sources often at or near sensors rather than at the TMC, can help ML models operate in real or near-real-time.

Holding computational resources constant, as data quantity and ML model complexity increase so too do the model training and execution times. For example, as part of NCHRP Research Report 997: Algorithms to Convert Basic Safety Messages into Traffic Measures (Vasudevan et al. 2022a), the research team recorded increases in ML model training and execution times as the market penetration rate of CVs increased (i.e., the quantity of data ingested increased). This project designed algorithms to detect and verify incidents algorithm and the queue length estimation. For details on the training and execution times as well as the server specifications behind the local computing resources used to train and execute the ML models, see Appendix C of Vasudevan et al. (2022a). These ML algorithms used simulated basic safety message (BSM) data, which behave more cleanly than real-world data. The training and execution times assumed no errors or gaps in communication and assumed the BSM data were already packaged and stored in the same location as the ML script, ready to run. These assumptions are unlikely to hold true in a real-world environment in which data can be messy and must be transmitted to different locations. To operate in real or near-real-time, ML applications are likely to require expanded computing resources.

Legacy systems used by many state and local transportation agencies often have insufficient data storage and computational power for ML applications (Vasudevan et al. 2022b). Researchers supporting the Iowa DOT pointed to the requirement of high-performance computing as a challenge to potential large-scale, statewide deployment of ML applications, based on information provided in their case study (see Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024). They also mentioned that large-scale deployment would require increased bandwidth to support real-time access to large amounts of data from sensors and cameras. In another example, because their existing data storage and computing power were insufficient, DelDOT purchased 10 servers to handle storage and computing to support their AI-ITMS, based on information provided in their case study (see Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024).

Cloud computing is another possible solution that has become increasingly popular as large tech companies expand their offerings, including integrated storage and computing services. Types of clouds include public (e.g., AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Platform), private (e.g., IBM Private Cloud, VMware vSphere), and hybrid clouds (e.g., OpenStack). Popular cloud service models that can apply across cloud types include Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Software as a Service (SaaS). These service models generally come with an initial set-up cost and then monthly costs depending on the scale of the data, features used, and level of access desired.

According to lessons learned from a case study on “Leveraging Existing Infrastructure and Computer Vision for Pedestrian Detection” in New York City (ITS Deployment Evaluation 2022b), cloud-based server and storage service is cheaper than using a local server in the short-term (i.e., less than 5 years). However, a local server could be a good option for testing or piloting an ML system since it is easy to set up. The cost to implement local server-based video data storage and networking services to support 68 traffic cameras in New York City was estimated at $1,663 per year (ITS Deployment Evaluation 2021). Similar cloud-based storage and computing services were estimated at between approximately $515 and $1,027 per year depending on how frequently the data are accessed based on Amazon’s public cloud service, AWS, using an Elastic Compute Cloud instance with 2 CPUs and 1 GB of memory, and Simple Storage Service (Ozbay et al. 2021).

Additional insights concerning computing are documented in the report on Artificial Intelligence (AI) for Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS): Challenges and Potential Solutions, Insights, and Lessons Learned (Vasudevan et al. 2022b). With a large amount of data being collected, transmitted, and processed to support ML, issues related to bandwidth and latency may still arise with cloud computing. Edge computing, which brings computing as close to the source of the data as possible to reduce latency and bandwidth use, could be a solution, especially for real-time and near-real-time ML applications. More than half of the respondents to a 2021 Sources Sought Notice on AI for ITS mentioned making use of edge computing in their AI-enabled applications, as noted in Appendix A of Vasudevan et al. (2022b).

Overall, as AI/ML solutions typically require significant computational resources and efficient communication networks to function properly, the interviewee from Caltrans suggested effective coordination with the agency’s information technology (IT) department (see Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024). Researchers for NCHRP Research Report 997 (Vasudevan et al. 2022b) made a similar recommendation to agency practitioners to assess the availability and maturity of their IT infrastructure and skillset to support big data processes (specifically for algorithms that use ML methods). While there is an upfront cost to upgrade digital infrastructure and likely monthly costs if using data storage and/or computing services, the benefit of doing so can be felt beyond ML applications at agencies.

Table 6 summarizes considerations for filling data storage and computing gaps.

Workforce and Organizational Considerations

A lack of workforce talent, education, and training is often cited as a major gap in the deployment and integration of AI systems into the operations of government agencies. ITS systems are usually operated and managed by engineers with civil engineering backgrounds, with degree programs that may have not started teaching AI concepts (Vasudevan et al. 2022b).

This often means AI/ML work done at state DOTs is done through contractors. In fact, much of state DOT work is outsourced. For example, one state DOT mentioned during a panel session at the American Society of Civil Engineers International Conference on Transportation and Development 2022 that it outsources 93–94% of its design work and over 60% of its

Table 6. Considerations for filling data storage and computing gaps to support ML.

| Considerations to Fill Data Storage and Computing Gaps |

|---|

|

construction and engineering work overall. Given that the general trend for state DOTs is to contract out a significant portion of work, the role of agency staff supporting ML projects is (usually) not as developers or programmers of ML applications, but rather as technical managers who need to understand strengths, weaknesses, and risks and to recognize unrealistic vendor claims (Vasudevan et al. 2022b).

The Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS) (INFORMS Organization Support Resources Subcommittee 2019) uses the terminology “readiness for analytics” to measure the success an organization will find when implementing analytics (including ML) projects, or what needs to change to improve odds of success. Among the indicators for success are belief and commitment from leadership that analytics add value to business

Insights from Case Studies on Workforce Considerations

(Chapter 3 in Cetin et al. 2024)

The Missouri DOT project team was a champion of the project even though its members did not consider themselves experts in AI/ML. They were able to get their leadership onboard with supporting the project by emphasizing the efficiencies and improved operational capacity that AI/ML could achieve. They won over operators by setting realistic expectations of system performance and emphasizing that the systems are not magic and would have to be improved and tuned over time but would nonetheless result in better outcomes.