Summary

COMPOUNDING DISASTERS IN THE GULF OF MEXICO REGION, 2020–2021

During 2020–2021, two global phenomena—the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change—shaped disaster risks worldwide, with particularly acute consequences in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM) region. The emergence and spread of COVID-19 transformed the public health risk of all other disaster events by amplifying health-compromising exposures and underlying vulnerabilities in the region. The pandemic also modified preparedness, response, and recovery procedures for the 2020–2021 extreme weather-climate events. The combined result was a complex and unprecedented public health and socioeconomic crisis—an exemplar of compounding disasters.

When society experiences a disaster, the impacts are typically attributed to an individual event, and damages stemming from disasters are quantified in terms of economic losses and direct fatalities. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s application of this conventional approach designated each of the seven major hurricanes and winter storm in the GOM in 2020 and 2021 as a billion-dollar disaster, and the COVID-19 pandemic has been characterized by some as a trillion-dollar disaster. These monikers, however accurate, do not reflect the human toll and disparate effects caused by multiple events that increase underlying physical and social vulnerabilities, strain adaptive capacities, and ultimately make communities

more sensitive and likely to experience future disruptive events as disasters. Such is the case for many GOM communities that were still in varying states of recovery from previous disasters when they were impacted by the compounding disasters of 2020–2021.

As climate change continues to affect every region on Earth in a multitude of ways, the adverse impacts on communities will only increase. Humans and the environments they inhabit will experience more extreme temperatures; stronger storms; more intense rainfall; and rising, warmer seas. These circumstances are influencing the chaotic characteristics of extreme weather-climate events, including the intensity, duration, and regional impact of occurrences.

In the GOM region, many communities are experiencing the increasing risk of the consequences of compounding disasters as the result of combined hazard exposure and vulnerabilities, many rooted in historic systemic and structural racial discrimination, including underinvestment in infrastructure and housing, persistent poverty, and land-use planning decisions that have marginalized people and placed them in harm’s way. These circumstances constrain the ability of residents to recover fully from disasters while increasing their sensitivity to the escalating effects of climate change and extreme weather-climate events. Consequently, perpetual disaster recovery, coupled with increasing disaster risk, is an enduring reality for many living in GOM communities.

STUDY CHARGE AND SCOPE

In 2022, the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine commissioned this study and tasked a seven-member ad hoc Committee on Compounding Disasters in Gulf Coast Communities, 2020–2021 with examining the unique characteristics and effects of the 2020–2021 compounding disasters in the GOM region, and examining how to manage and minimize the effects of these disasters on those who live and work in the region. Committee members were invited to serve because of their extensive academic and professional expertise in community resilience; disaster management; public health; and behavioral, social, and atmospheric sciences. The committee’s charge included the following tasks:

- Describe the major disasters that occurred in the Gulf region during the 2-year period and, to the extent known, their impacts on

- community markers such as local economies, government functions, industry, the education system, human health, and social structure.

- Discuss how these impacts were compounded by the sequencing of events, as well as the factors that may have amplified these impacts (e.g., poverty, health disparities, economic and governance constraints, obsolete or inadequate infrastructure).

- Identify lessons learned from and needs exposed in how communities dealt with these compounding disasters.

- Provide findings on what factors enabled or could enable communities to successfully plan for, respond to, recover from, and mitigate the impacts of compounding disasters.

With nascent research on this topic, particularly within the context of the GOM during the period 2020–2021, the committee emphasized qualitative, primary data collection through information-gathering sessions with key informants in the GOM region and the review of locally generated after-action reports and other primary and secondary sources as its approach to the statement of task. Additionally, the committee commissioned two papers to supplement its deliberations: the first provides an exploration of health and community baseline conditions and disaster impacts in two Mississippi counties; the second offers a geospatial analysis of localized hazards, vulnerability, and exposure across the GOM region. These learnings were then contextualized within relevant scientific literature, including completed National Academies consensus study reports, to support the development of the committee’s findings and conclusions. This methodology allowed the committee to meet its task by documenting compounding disasters’ effects in a specific region within a specific time frame, from the lived experience and perspectives of those affected. The committee was not tasked with offering recommendations.

CONCEPTUALIZING COMPOUNDING DISASTERS

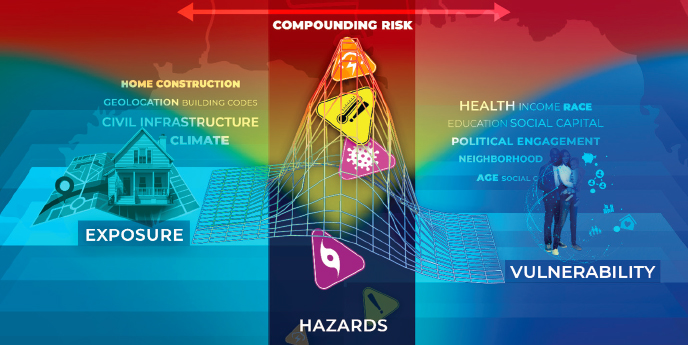

Drawing on existing frameworks derived from disaster scholarship, the committee began its inquiry by examining a conventional Venn diagram that contemplates disaster risk as the product of intersecting hazards, exposure, and vulnerability, as illustrated by Figure S-1.

Within each lens of this framework lie numerous layered and interrelated drivers of risk. For the purposes of this report, the committee adopted the use of the following definitions:

SOURCE: Adapted from Figure 19-1 in M. Oppenheimer, M. Campos, R. Warren, J. Birkmann, G. Luber, B. O’Neill, and K. Takahashi, 2014: “Emergent risks and key vulnerabilities”; in Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. R. Mastrandrea, and L. L. White, eds. Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom and New York, pp. 1039–1099.

- Hazards are understood to be processes, phenomena, or activities with the potential to “cause loss of life, injury or other health impacts, as well as damage and loss to property, infrastructure, livelihoods, service provision, ecosystems, and environmental resources” (USGCRP, 2023). Hazards may be natural or human-made and can occur individually or simultaneously. Examples of hazards reflected in this study include severe and extreme weather events and the global COVID-19 pandemic.

- Exposure describes the presence of people, infrastructure, housing, production capacities, and other tangible human assets in hazard-prone geographies or situations.

- Vulnerability encompasses social and economic sensitivities of individuals and groups, along with deficiencies in the structures and

- systems on which they rely, that reduce their capacity to withstand hazards. Vulnerable communities are those least able to anticipate, cope with, and recover from these disruptive events.

- Disaster risk is expressed as a product of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability variables and understood as the potential for loss of life, injury, physical damage, or destruction resulting from the occurrence of one or more disruptive events in a given period.

Accordingly, realized disaster impacts are products of not only the severity or intensity of the hazard itself, but also the combination of vulnerability and exposure—or sensitivity—of the community and its underpinning systems and functions to suffer loss and damage. Many communities in the GOM region exist in a state of heightened disaster risk and perpetual recovery. As a result, the systems and functions that underpin communities are progressively diminished. From a humanitarian perspective, the immediate, visible, and experiential effects of disasters cannot be decoupled from the preexisting conditions of exposure and vulnerability that produce sensitivity to the event while also increasing sensitivity and risk to future events. As such, the disaster management enterprise must be responsive not only to the occurrence of singular and multiple disruptive events but also to the persistent societal conditions that create sensitivity to future disasters and compose the epoch nature of the compounding effects of disasters within disaster survivors’ lives.

To guide its exploration of this topic, and for the purposes of this study, the committee characterizes a compounding disaster as the result of overlapping, concurrent, or successive disruptive events that affect the societal, governmental, and/or environmental functions of a community or region and diminish the community’s capacity to recover and resume essential activities. The weakening of these interrelated functions inhibits and prolongs the disaster recovery period, making communities more likely to experience amplified negative effects of future disruptive events. Some communities are at disproportionate risk of suffering the effects of compounding disasters as a result of the interplay of persistent physical and social vulnerability factors and increased exposure to climatic and non-climatic hazards.

There is nothing linear about the movement of hazards, exposure, vulnerability, and the resulting risk. Through its deliberations, the committee found the conventional Venn diagram and its various two-dimensional iterations constrained in representing the multidimensional dynamics of

compounding disasters. The common definitions of hazard(s), exposure, vulnerability, and risk continue to ring true, yet the ways that risk compounds requires a more integrative visualization, as depicted in Figure S-2.

The interaction and agitation within and among these variables is dynamic and complex. Realized hazards, experienced by communities as disruptive events, stack upon each other and exacerbate vulnerability and exposure. As the impacts of disruptive events compound, they push the interconnected societal mesh spanning multivariable exposure and vulnerability planes toward ever-increasing risk to future disruptive events.

Exposure and vulnerability increase (and decrease) by a range of choices made affecting variables within a community. These choices affect the adaptive capacity of a community to prepare for, respond to, and recover from disruptive events and disasters. As described throughout the report, increasing adaptive capacity is an intentional and effective way to pull down risk by reducing variables associated with exposure and vulnerability within and across societal systems.

FEATURES OF COMPOUNDING DISASTERS

Among the features of compounding disasters, four stand out as especially salient to GOM communities and the purpose of this study: (1) the disproportionate risk faced by vulnerable communities; (2) outcomes that result when that risk becomes realized impact; (3) effects

SOURCE: Image provided courtesy Insurance Institute for Building and Home Safety (IBHS).

on the interdependent systems and functions that serve both the routine and the acute needs of a community; and (4) overlapping, interrupted, and prolonged disaster recovery.

Particular Risk to Vulnerable Communities

Disasters manifest when a community’s capacity to prepare for, respond to, and recover from the occurrence of a disruptive event is inadequate and overwhelmed. When compounding effects occur over time communities may bear the hardship of disaster without ever reaching traditional thresholds for a formal disaster declaration. It is the sensitivity of those who experience the brunt of the disruptive event that dictates whether the experience crosses the threshold to become a disaster. Heightened socioeconomic vulnerabilities and disaster-weakened systems and functions make many GOM communities particularly sensitive to future disruptive events and their compounding effects, regardless of the events’ intensity. Many frontline communities (those who are highly exposed to climate risks due to where they live and the projected changes expected to occur in those places) have fewer resources; lower adaptive capacity; weak social or economic safety nets; and/or are underrepresented in policy, governance, and recovery planning (USGCRP, 2023) to be able to reduce sensitivity.

The committee explored the evidence-based disaster risk profile of GOM communities, including first-hand accounts of information-gathering session participants about the pandemic and extreme weather-climate events’ impacts in 2020–2021. The events discussed were not restricted to federally declared or billion-dollar disasters, but included “smaller” disruptive events (e.g., heavy precipitation events, isolated tornados) that can compound in their effects and produce large-scale impacts. Risk profiles include components of physical, health, and social vulnerability, and exposure to extreme weather-climate events and hazards familiar to the region.

When Disaster Risk Becomes Realized Impact

The time frame for this study provides insight into outcomes that result when disaster risk becomes repeated realized impacts. Through a series of facilitated regional dialogues, detailed in Chapter 3, the committee engaged community leaders and practitioners who experienced multiple disruptive events in 2020–2021. Although the type, intensity, and location of these

events varied, their rapid succession resulted in shared experiences across regions. Throughout its process, the committee sought to better understand the realized impact of multiple disruptive events on the function, resilience, and well-being of disaster-affected communities, including those who work in service to them.

Effects on Interdependent Community Systems and Functions

Chapter 4 details the widespread and profound compounding disaster impacts on the interdependent systems and functions that enable communities to function properly, and often result in prolonged—if not indefinite—recovery. Moreover, the longer recovery periods extend, for any household or community, the more likely it is that damage, losses, and the human toll will be compounded by one or more future disruptive events. In Southwest Louisiana, the February 2021 winter storm brought extreme cold weather with freezing rain, causing pipes to burst and acutely affecting water systems for homes and public buildings such as hospitals and dialysis centers that were still in disrepair from a previous pair of hurricanes. Three months after the winter storm, a heavy May rainstorm brought a foot of rain in less than 24 hours to areas affected by Hurricanes Laura and Delta in 2020, further exacerbating ongoing recovery efforts. Debris not yet removed from the 2020 storm sequence clogged stormwater systems, limiting the capacity available to absorb or drain the record rainfall. The floodwaters initiated yet another round of losses and claims into an already overwhelmed claims and assistance system that was unable to quickly mobilize funds into Southwest Louisiana, particularly Lake Charles.

Overlapping, Interrupted, and Prolonged Recovery

In many cases, the rapidity of event occurrence, coupled with overlapping, interrupted, and prolonged recovery periods, made it difficult if not impossible for residents, municipalities, claims adjusters, and responding federal agencies to differentiate among or ascribe realized impacts to specific disruptive events. Chapters 3 and 4 provide examples, including how in both Alabama and Louisiana, two hurricanes made landfall in such rapid succession that residents, building officials, and claims adjusters had difficulty accurately assigning damage to the causal event. As a result, many residents experienced delays or were unsuccessful in their attempts to effectively file claims and receive reimbursements or public assistance for

disaster damages. As the disaster recovery period is prolonged, sensitivity to the occurrence of future disruptive events is heightened.

Lessons Learned and Lessons Lost

The compounding disasters within the time frame of this study cannot be isolated from prior disasters. Each region’s session participants acknowledged being in some state of recovery from the physical and socioeconomic impacts of previous disasters, such as Hurricanes Katrina and Rita (in 2005), the Deepwater Horizon disaster (in 2010), Hurricanes Gustav and Ike (in 2008), and Hurricane Harvey (in 2017). Despite their widespread and devastating impacts, these prior events provided policy- and decision-makers with opportunities to learn from experience and make improvements to reduce future disaster risk. Chapter 5 examines how these experiences from previous disasters influenced communities’ experiences in 2020–2021, while identifying barriers that may inhibit the uptake of lessons learned.

CONCLUSIONS:

REDUCING COMPOUNDING DISASTER RISK BY ADDRESSING VULNERABILITIES AND EXPOSURE AND BUILDING ADAPTIVE CAPACITIES

The committee’s information-gathering, analysis, and deliberations yielded a number of conclusions regarding the compounding disasters that occurred in the GOM region in the 2020–2021 time frame. Grounded in the profound experiences relayed to the committee by the affected communities during the course of this study and reinforced with the scientific evidence base, the conclusions presented here and in Chapter 6 underscore the need to reimagine efforts that support disaster preparedness, mitigation, and recovery in an era of intensifying extreme weather-climate events and increased risk of compounding disasters. Conclusions 1–3 address the expanding realities of compounding disaster risk; conclusions 4–6 identify the need for improving and expanding our understanding of the new scale and temporal scope of compounding disasters; conclusions 7–9 refer to the need to bolster public health, mental health, and community-based organizations and their adaptive capacity; and conclusions 10–14 identify new approaches to contending with compounding disasters. The conclusions are based on the committee’s information gathering and analysis of disasters in

GOM communities, and they are not necessarily generalizable to communities experiencing disasters in other regions.

The Expanding Realities of Compounding Disaster Risk

Conclusion 1: Compounding disasters introduce new, interconnected, and complex risk scenarios due to the increased potential of multiple hazards overlapping in time and space.

As established in Chapter 2, recent studies in attribution science show that climate change is causing an increase in the frequency and/or severity of tropical storms, heavy rainfall, and extreme temperatures. The intensification of these and other more extreme weather-climate events are intersecting with areas experiencing high levels of health disparities, social vulnerabilities, and increased exposure due to population growth in hazard-prone areas. This convergence is resulting in prolonged and overlapping periods of disaster recovery. While hazards may be unalterable, their impact can be reduced by collectively building adaptive capacity—whether preemptive, in real time, or through the recovery process—within vulnerable and exposed systems, institutions, and people.

Conclusion 2: Increased compounding disaster risk requires communities to plan and prepare for the co-occurrence of multiple and varied disruptive events that interact with societal exposure and vulnerabilities to amplify overall disaster impact.

Two phenomena of global scope and scale—the sudden emergence and ongoing evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change—fundamentally influenced concurrent disaster events more circumscribed in time and place. The evidence presented in Chapter 3 makes clear that while GOM communities have plans in place for addressing more common climate hazards (i.e., hurricanes), the same level of planning did not exist for less common events (i.e., Winter Storm Uri, the COVID-19 pandemic), let alone the co-occurrence of multiple events. Advancing adaptive capacity involves understanding how disaster events impact specific localities and funding locally led, long-term planning for risk reduction and climate adaptation programs. Such programs must advance with built-in flexibility to respond to evolving priorities.

Conclusion 3: When a community increases its capacity to absorb the effects of hazards and minimizes its recovery needs, disaster effects are less likely to compound.

Targeted, community-guided investments to increase the resilience of essential services and infrastructure are important to achieve this objective. While it is preferable to invest before a disaster occurs, for those communities able to access such investments, the influx of recovery funding after a disaster can provide an opportunity to mitigate future losses and the potential for compounding disasters. As discussed in Chapter 5, many information-gathering session participants highlighted the importance of flexible pandemic relief funds as an invaluable asset to help their communities recover. The literature on social capital discussed in Chapter 2 and the comments made by information-gathering session panelists both emphasize the critical role of social capital and cohesion in building resilience and catalyzing recovery from disaster events. Investments into building physical capacity to withstand hazards are essential, but the strengthening of adaptive capacity, including formal and informal relationships among community stakeholders is equally foundational to disaster resilience.

The New Scale and Temporal Scope of Compounding Disasters

Conclusion 4: Perception and understanding of risk are commonly grounded in past experience, leading to complacency in preparation and mitigation.

As discussed in Chapter 3, cognitive biases such as recency bias and normalcy bias can lead to inaccurate conceptualizations of past events and can hamper risk communication, mitigation, and planning for future events that extend beyond what has been experienced or is perceived to be the benchmark extreme. These biases are similarly reflected in emergency management protocols, land-use planning and plans, zoning regulations, public utility design, and building codes, which are often grounded in historical precedent or probabilistic hazard descriptions derived from historical data. Given a changing climate, this hindcasted vantage is unlikely to be representative of future hazard risks. Overcoming these biases requires new strategies.

Conclusion 5: Effective disaster recovery requires an “epoch” rather than “event” view that more fully captures the prolonged effects of compounding disasters and reflects the experienced reality of the community.

In the information-gathering sessions summarized in Chapter 3, participants continually reported that the impacts of discrete disaster events were impossible to disentangle when the disasters occurred in such rapid succession and their recovery time lines overlapped. This was particularly true in socially vulnerable communities that were inadequately resourced before disaster events. An event-based perspective on disaster management is inherently narrow, reactive, and artificially time constrained. The event-driven view focuses on the symptoms rather than the root causes of disaster losses. Shifting to an epoch view better frames the breadth of lived experiences with disasters and accounts for the potential for compounding losses, driving the broad disaster response and recovery enterprise to more comprehensive and effective pathways forward.

Conclusion 6: Risk assessment and communication for extreme weather-climate and multiple/sequential events is inadequate for both current and future conditions.

The severity of many of the disaster impacts in 2020–2021 exceeded expectations. With a changing climate, the potential for complex events only increases. As described in Chapter 3, many information-gathering session participants brought to light a variety of disaster communication challenges that were exacerbated by the compounded nature of events, including inconsistent technology and broadband access, accommodating non-literate populations, lack of public trust in government, and the spread of misinformation. Better preparation for future compounding events requires incorporation of compound event risk assessments, multisector collaboration, and improved risk communication. The multiple levels of a participatory information-sharing approach will increase understanding of the unique needs of socially vulnerable groups, enhance transparency, and reduce the potential for misinformation.

Bolstering Adaptive Capacity

Conclusion 7: Health care and public health systems will require increased adaptive capacity and staffing to respond to diverse challenges posed by compounding disasters.

Compounding disasters notwithstanding, health systems in the GOM region are already vulnerable and struggle to meet the needs of GOM populations, as discussed in Chapter 2. Recent literature and information-gathering session participants made clear the increased strain on health systems caused by the co-occurrence of natural hazards and the COVID-19 pandemic. The nature of the hazards encountered influences the impacts on population health, health systems, and public health services. Even as extreme weather-climate events damage facilities and disrupt access to health care, emerging disease outbreaks require physically intact facilities and enough frontline professionals staffing them so that services can be rapidly shifted to communicable disease care, and local public health capacity can be maintained.

Conclusion 8: Pervasive mental health impacts of compounding disasters undermine the adaptive capacity of communities to withstand and effectively recover from disruptive events.

Information-gathering session panelists spoke extensively about the negative mental health impacts of compounding disasters on survivors, especially for specific subpopulations, such as first responders and volunteers. The impacts of disasters on behavioral health are pervasive, extend across a spectrum of severity, and may continue for a prolonged time. Chapter 2 details some of these specific impacts and explores the links between disaster exposure and adverse psychological and behavioral health outcomes. Mental health needs are magnified for those who experience more intense exposure and vulnerability to hazards. Particular attention is necessary to the mental health needs of those who are disproportionately affected psychologically, including children; the elderly; medically high-risk patients, including those with severe mental illness; and the frontline professionals including first responders, public health professionals, and volunteers tasked with disaster response and recovery responsibilities.

Conclusion 9: The heavy dependence on community-based organizations can strain these individuals and groups beyond the point of effectiveness in the face of compounding disasters.

In the aftermath of a disaster, many immediate needs are met by neighbors helping neighbors and community-based organizations. As discussed in Chapter 4, information-gathering session participants, particularly those representing nongovernmental and community-based

organizations, consistently reported feeling burned out and overwhelmed from spending long hours providing physically and/or emotionally taxing labor for little compensation. While these volunteers and organizations are essential to disaster response and recovery, they may suffer from the compounded disaster impacts themselves and be unable to assist when needed most. Overreliance on this often uncompensated or underpaid workforce risks the depletion of critical human resource capacity for effective long-term recovery from successive disasters.

New Approaches to Contending with Compounding Disasters

Conclusion 10: While a powerful tool for delivering services in times of crisis, technology is not a universal substitute for interpersonal communication and in-person disaster recovery assistance.

COVID-19 restrictions forced rapid innovations, creating more efficient ways to share critical data digitally and greater agility in delivering services virtually—adaptive shifts that were invaluable to service continuity when storms disrupted physical operations. However, as discussed in Chapter 4, processing federal disaster recovery assistance requests and insurance claims virtually caused errors and inefficiencies for survivors. Vulnerable populations, notably the elderly and low socioeconomic status individuals, are often least equipped to navigate complex and continually evolving online systems. For these populations, the reduction or elimination of in-person assistance prolonged disaster recovery efforts and increased risk for future disruptive events.

Conclusion 11: Safe, sanitary, and secure housing is a fundamental determinant of disaster resilience and recovery, and can thus be viewed as core community infrastructure.

As established in Chapter 2, access to stable, long-term housing is critical for individual and collective well-being, and displacement from secure housing has deleterious impacts on security, mental health, social connectedness, and well-being broadly. Since the most vulnerable housing (older/deferred-maintenance properties) is often occupied by the most vulnerable households, this segment of the inventory is especially susceptible to compounding disasters, even as the result of lower-intensity weather-climate events. Areas experiencing economic downturns or with aging housing inventories require particular

attention to housing quality as part of ongoing efforts to address the broader affordable housing crisis that existed well before 2020.

Conclusion 12: Effective community-guided risk reduction for compounding disasters requires greater understanding of and planning for the full range of potential disruptive events, along with their cumulative effects.

Chapter 2 outlines the wide range of both hazards to which GOM populations are exposed and the impacts that these hazards can have on human health and well-being. These can be low- or high-probability events, and can span climatic (e.g., rapidly intensifying storms, slow-moving and stalling storms dropping significant rainfall, temperature extremes) and non-climatic (e.g., pandemic, technological) scenarios, including worst-case extremes. Local-level participatory planning processes that routinely engage and collaborate with socially vulnerable communities that are marginalized by lack of representation in policy, governance, and recovery planning; income; education; age; ethnicity/race; gender; sexual identity; and/or medical risk and that are disproportionately affected by compounding disasters will more effectively guide and prioritize efforts to reduce potential impacts and concurrently build adaptive capacity.

Conclusion 13: Stronger mechanisms are essential to translate lessons recognized from prior experience into lessons learned and implemented.

As discussed in Chapter 5, lessons are often identified after disasters, but they are rarely codified into formal policies and procedures before the next disaster strikes. Interaction between professionals and community members can relay local disaster memories to agency personnel. Ongoing and inclusive education, training, drills, and scenario-based exercises can perpetuate and reinforce lessons learned among all affected communities and decision-makers. Collaborative input of lessons learned into after-action reports can increase knowledge base, participation, and potential for implementation. Efforts at all levels of government to dissolve institutional silos and reinforce improved practices can also sustain lessons learned between disasters.

Conclusion 14: Revisions to disaster planning, response, and recovery policies and procedures need to directly address and eliminate the uneven access to resources that can exacerbate social and economic inequities in the wake of disasters.

Residents in affected areas with the most financial means, social capital, and technological skills are able to more effectively access recovery resources; compounding disasters can leave those without such critical capabilities in a more distressed condition, and even minor disruptive events can become disasters. As discussed in Chapter 2, a large portion of GOM residents are in some capacity marginalized, and the current disaster recovery process often exacerbates vulnerabilities rather than addressing these vulnerabilities at their root. Information-gathering session participants highlighted the need to incorporate equity into the disaster recovery process to better assist marginalized, socially vulnerable community members.

The climate-intensified stress on people, communities, and the systems and functions that support them; disruptive events; and disaster risk will likely continue to increase, along with the likelihood that more communities will experience the debilitating effects of compounding disasters. The committee recognizes that transdisciplinary research and applied science in disaster resilience continues to advance in the wake of major events in the United States and around the world. This study is intended as a contribution not only to the evidence base but in support of continued research and calls for collective community-guided action and investment to reduce systemic vulnerabilities, mitigate hazard exposure, and increase adaptive capacities to enable communities to address effectively the complex challenges that confront them.