Driving Action and Progress on Obesity Prevention and Treatment: Proceedings of a Workshop (2017)

Chapter: 1 Obesity Trends and Workshop Overview

1

Obesity Trends and Workshop Overview

After decades of increases in the obesity rate among U.S. adults and children, the rate has recently dropped among some populations, particularly young children (Fryar et al., 2012, 2014; Ogden et al., 2016). What are the factors responsible for these changes? How can promising trends be accelerated? What else needs to be known to end the epidemic of obesity in the United States?

To examine these and other pressing questions, the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions, which is part of the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, held a workshop in Washington, DC, on September 27, 2016, titled “Driving Action and Progress on Obesity Prevention and Treatment.”1 The workshop brought together leaders from business, early care and education, government, health care, and philanthropy to discuss the most promising approaches for the future of obesity prevention and treatment. More than 100 people attended the workshop in person, with several hundred more watching a live webcast.2 Box 1-1 provides the workshop’s complete statement of task; the workshop agenda appears in Appendix A; acronyms and abbreviations found throughout this proceedings are defined in Appendix B; and biographies of the speakers and facilitators are provided in Appendix C.

___________________

1 The planning group’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and this Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteur with staff assistance as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop.

2 The webcast is available at http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/Activities/Nutrition/ObesitySolutions/2016-SEPT-27.aspx (accessed January 12, 2017).

The Roundtable on Obesity Solutions was established in 2014 to engage leaders from multiple sectors, including health care, academia, business, health insurance, education, child care, government, media, philanthropy, and diverse nonprofits, to help solve the nation’s obesity crisis. The roundtable provides for inspiration and the development of multisector collaborations and policy initiatives aimed at preventing and treating obesity and its adverse consequences throughout the life span. It is also focused on eliminating obesity-related health disparities. A major purpose of the roundtable is to examine and promote dialogue around successful on-the-ground implementation of multisector solutions.3

U.S. TRENDS AND PREVALENCE

___________________

3 To learn more about the roundtable, visit http://nationalacademies.org/HMD/Activities/Nutrition/ObesitySolutions.aspx (accessed May 24, 2017).

In the first presentation of the workshop, Captain Heidi Blanck, chief of the Obesity Prevention and Control Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), provided an overview of U.S. trends and prevalence in overweight and obesity to establish a framework for the ensuing discussion.4 Obesity is associated with poorer health from physical and mental health conditions, she explained. It increases the risk of heart disease; stroke; type 2 diabetes; lung disease, including asthma; liver disease, including fatty liver; certain types of cancer; infertility; and a host of other problems (CDC, 2015). Excess weight “isn’t just a cosmetic issue,” Blanck stated. Obesity is “putting our children [and] adults at risk for early disease and early death.”

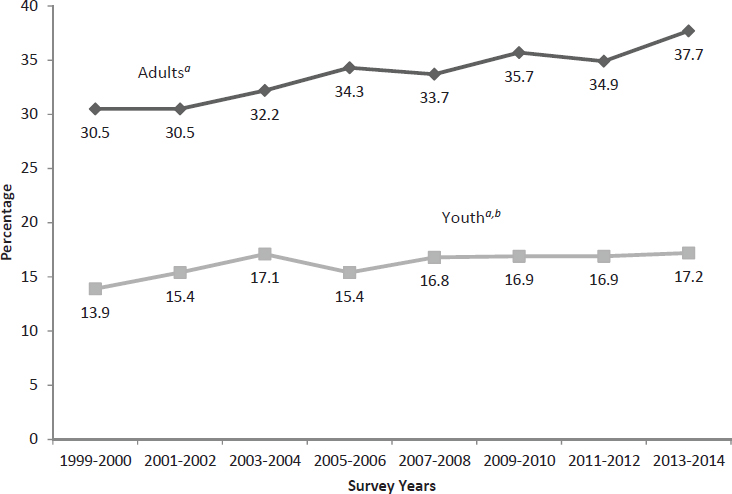

According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), more than one-third of adults in the United States have obesity; the first 15 years of the 21st century saw an increase in obesity prevalence of about 7 percentage points (Ogden et al., 2015) (see Figure 1-1). This percentage translates to 82.7 million U.S. adults struggling with obesity. And more than two-thirds of U.S. adults—71 percent—either have obesity or are overweight (CDC, 2016c). Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System5 show a slower rate of increase in the prevalence of self-reported obesity among U.S. adults by state and territory since 2011, when the survey methodology was changed to ensure better representation of the U.S. population, Blanck explained (CDC, 2016a). Still, these self-reported data, like measured data, also show disparities by race/ethnicity.

Obesity is higher among women than men (38.3 percent versus 34.3 percent), and among people over 40 years old (40.2 percent for those aged 40–59; 37 percent for those aged 60 and over) than those aged 20–39 (32.3 percent) (Ogden et al., 2015). Obesity is also higher among African Americans and Hispanics (48.1 percent and 42.5 percent, respectively) than among non-Hispanic whites (34.5 percent) and non-Hispanic Asian Americans (11.7 percent), again with higher rates for women than men (Ogden et al., 2015). As Blanck pointed out, 56.9 percent of non-Hispanic black women and 45.7 percent of Hispanic women are struggling with obesity—a clear disparity by race/ethnicity (Ogden et al., 2015). In addition, she explained, birth certificate data show that 24.8 percent of women who gave birth in 2014 had obesity before becoming pregnant (Branum et al., 2016), thereby facing an increased risk of gestational diabetes and other maternal morbidities and mortalities.

___________________

4 The findings and interpretation in her workshop presentation are solely her views and do not represent the official views of the CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

5 See https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html (accessed November 22, 2016).

NOTE: All adult estimates are age-adjusted by the direct method to the 2000 U.S. census population using the age groups 20–39, 40–59, and 60 and over. aSignificant increasing linear trend from 1999–2000 through 2013–2014. bTest for linear trend for 2003–2004 through 2013–2014 not significant (p >0.05).

SOURCES: Ogden et al., 2015. Presented by Heidi Blanck, September 27, 2016 (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db219.htm [accessed November 14, 2016]).

CHILDHOOD OBESITY TRENDS

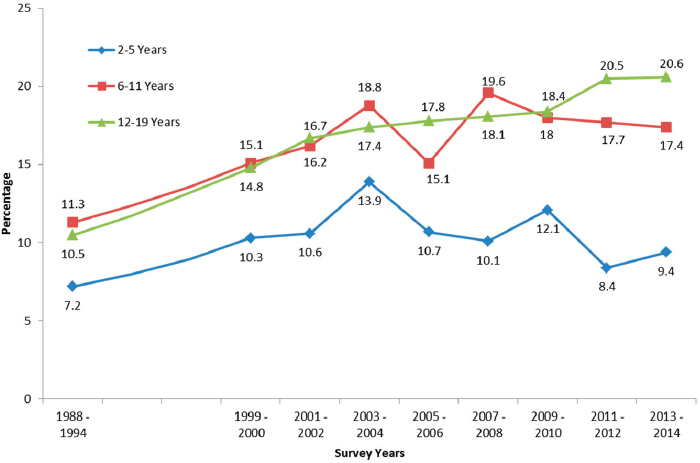

According to NHANES data, obesity rates have increased substantially among U.S. youth aged 2–19 over the past three decades (see Figure 1-2). Among 12- to 19-year-olds, obesity almost doubled between 1988–1994 and 2013–2014 (Ogden et al., 2016). Starting in the late 1980s, the rate also rose appreciably for 6- to 11-year-olds and for 2- to 5-year-olds (Ogden et al., 2016). Altogether, 12.7 million U.S. youth are struggling with obesity, according to the most recently available data. Furthermore, extreme obesity rose in 12- to 19-year-olds from 2.6 percent in 1988–1994 to 9.1 percent in 2013–2014. “This is definitely an area where we need to be thinking about resources and strategies,” Blanck said.

However, some promising signs have started to emerge in recent years, Blanck observed. The prevalence of obesity declined among 2- to 5-year-olds between 2003–2004 and 2013–2014, from 13.9 percent (95 percent

NOTE: Obesity is defined as at or above the sex-specific 95th percentile of body mass index (BMI)-for-age Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth charts; extreme obesity is defined as 120 percent of the sex-specific 95th percentile of BMI-for-age CDC growth charts.

SOURCES: Ogden et al., 2016. Presented by Heidi Blanck, September 27, 2016.

confidence interval [CI], 10.7–17.7 percent) in 2003–2004 to 9.4 percent (95 percent CI, 6.8–12.6 percent) (p = 0 .03) in 2013–2014. Similarly, after reaching a peak of 19.6 percent in 2007–2008, the prevalence among 6-to 11-year-olds has since held steady (Ogden et al., 2016). “We’re hoping that [these data show] that we’re aiding the ability for the youngest of our children to thwart obesity,” Blanck said.

Disparities in obesity rates also are evident in the data from this period for 2- to 19-year-olds, with prevalence being lowest among Asian Americans (8.6 percent), higher for non-Hispanic whites (14.7 percent), and highest among non-Hispanic blacks (19.5 percent) and Hispanics (21.9 percent) (Ogden et al., 2016). Among low-income 2- to 4-year-olds enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) whose data were part of the CDC’s Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System, obesity rates rose from about 13 percent in 1998 to just under 15 percent in 2011 (Pan et al., 2015). Among non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander children, the rates

decreased, Blanck observed. The exception, she continued, was American Indian and Alaska Native children enrolled in WIC, who experienced obesity at a rate of 21 percent in 2011.

Another hopeful sign Blanck described comes from state-level data on changes in obesity rates among low-income 2- to 4-year-olds (CDC, 2013). Between 2008 and 2011, 19 states saw a small but significant decline in childhood obesity, while only 3 saw increases (CDC, 2013). Blanck noted that the CDC will soon release data from a new biennial monitoring system for children in the WIC program—the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s WIC Participant Characteristics Survey—that found the prevalence of obesity and overweight to be 31.2 percent among 2- to 4-year-olds in 2012 (HRSA, n.d.), with lower rates among non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders and higher rates among Hispanics and American Indians and Alaska Natives. Another promising trend, Blanck said, can be seen in data from a few locations across the country, including the New York City public schools, generated by the use of FitnessGrams®, with rates of obesity declining slightly since 2006–2007 (Berger et al., 2011). Still, she noted, disparities persist in many communities; for example, African American and Hispanic children experienced obesity at a higher rate than their white and Asian/Pacific Islander counterparts.

IMPROVED MONITORING

“We’re starting to see some great local success stories,” said Blanck. But she argued that improvements in the quality of monitoring efforts and interpretation of short-term data need to be considered. For example, NHANES has fewer than 1,000 children in its 2- to 5-year-old 2-year sample (e.g., 2013–2014, versus more stable estimates when the data are pooled across the 2011–2014 cycles), and it often takes about 2 years for the data to become available to the public. Moreover, researchers may need additional training in or knowledge of post hoc approaches for data cleaning to minimize errors and bias when working with data from HeadStart and FitnessGram® or self-reported data.

Combining data from different sources, such as birth certificates and vital statistics, can help fill some of the current gaps in obesity surveillance, Blanck suggested. Also, new technologies such as electronic health records provide opportunities to facilitate surveillance and improve public health. A specific example cited by Blanck is an open-source platform that can aid in the exchange of information—known as Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources—by helping to harness data from electronic health records for public health monitoring. “As entities move forward in negotiating data sharing agreements with health care,” she said, “public health jurisdictions across the country are going to be able to monitor body mass index

and see whether their state and local programs and policies are making a difference.” Monitoring of data from other sources, such as data on state and district policies and practices in schools and early care and education programs, community built environments, consumption of fruits and vegetables, food insecurity, breastfeeding rates, and physical activity, can provide information on the broad array of behavioral and social influences that affect weight, she explained.

Anticipating discussions in the remainder of the workshop, Blanck observed that a broad array of societal and community factors can have an influence on weight. Retrospective analyses of places where obesity among children has declined, she noted, have pointed to such factors as policies related to nutrition and physical activity—for example, child care and school wellness policies. In particular, she emphasized the presence of strong community coalitions in places where obesity has declined, entailing “engagement with business leaders, engagement with child care and schools, engagement with parents.” Researchers are also continuing to look at additional factors related to energy balance, including the microbiome, sleep, stress, and environmental chemicals. Simple fixes cannot be expected, Blanck concluded, but evaluations of success and continued surveillance and research can support further progress.

THEMES OF THE WORKSHOP

Bill Purcell, currently with Farmer Purcell & Lassiter, PLLC, and former mayor of Nashville, Tennessee, summarized general themes he had identified during the workshop presentations and discussions. These themes are presented here as an introduction to the topics discussed during the workshop and should not be viewed as the conclusions of the workshop as a whole:

- Multifactorial and multisectoral approaches with coordination at all levels and in all sectors can help end the obesity epidemic, Purcell reflected. Key factors include making obesity relevant to everyone, addressing the social determinants of health, sharing progress, staying the course, and making sure that everyone knows what to do. (Chapter 2)

- In early care and education, promising approaches exist for practice, training, technical assistance, and self-assessment for improvement, Purcell noted, referring to the panel discussion. Important issues remain, however, including disseminating and scaling up these approaches, achieving equity, dealing with funding limitations, and translating research results into sustainable programs. (Chapter 3)

- Many businesses are developing a new awareness of their potential role in health and well-being, Purcell said, with some businesses being described as bridging the gap between profit and purpose. The results in some cases have been transformative. But the individual panelists on this topic advised that difficult conversations will be necessary to tap this resource, along with incentives that encourage and enable businesses to change. (Chapter 4)

- The session on physical activity revealed that U.S. children are among the least physically active in the world, Purcell noted, although there has been some improvement since 2008. Physical activity interventions can make a difference, but few are widely implemented, often for reasons of cost. Training and technical assistance can improve the implementation of such interventions, and advocates and leaders can champion the cause, recounted Purcell. (Chapter 5)

- The treatment of obesity is a challenge, observed Purcell, with more than 17.6 million Americans having severe obesity and just 1,600 new doctors being certified in obesity medicine each year. He noted several challenges that speakers had identified, including gaps in treatment capacity, guidelines, insurance coverage, and understanding of disparities among groups that additional research could help bridge. Only 25 percent of physicians report that they have had enough training to talk with their patients about obesity. Speakers during the treatment panel suggested taking an integrated approach, paying more attention to social programs, and developing common definitions and competencies as possible solutions. (Chapter 6)

- The U.S. Department of Agriculture has played an important role in federal efforts to prevent obesity, Purcell summarized. Through the WIC program, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and the MyPlate guide, it acts to address problems at multiple societal levels and accelerate progress on many fronts. (Chapter 7)

- Philanthropists have supported work on obesity prevention and treatment for decades, noted Purcell, and the speakers on the philanthropy panel stated that they will continue to support this work. (Chapter 8)

- Purcell encouraged foundations and other advocates to remain committed for the long haul, because ending the obesity epidemic will require a sustained commitment. Staying the course, he suggested, includes developing a better understanding of what can work at the street level, the neighborhood level, the store level, the regional level, and the national level.