Aligning Investments in Therapeutic Development with Therapeutic Need: Closing the Gap (2025)

Chapter: 2 Conceptual Foundations for Measuring Disease Burden, Unmet Need, and Investment in Therapeutic Development in the United States

2

Conceptual Foundations for Measuring Disease Burden, Unmet Need, and Investment in Therapeutic Development in the United States

In a 1998 report from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) titled Scientific Opportunities and Public Needs: Improving Priority Setting and Public Input at the National Institutes of Health, a key recommendation was for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to “strengthen its analysis and use of health data, such as burdens and costs of disease,” in determining priorities (IOM, 1998a, p.5). A study by Gross and colleagues (1999), published soon after the release of the IOM report compared NIH funding across disease areas in 1996 against several measures of disease burden, including total mortality, years of life lost, disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), hospital days, incidence, and prevalence. The study found that funding was strongly correlated with the number of DALYs but not with the other examined metrics, and it identified specific examples of disease areas that were funded at high or low levels relative to disease burden. In addition to the Gross study, a number of other studies have used similar designs to examine the relationship between burden of disease and research funding from NIH (Carter and Gevorkian, 2025; Rees et al., 2021) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Curry et al., 2006). These studies have commonly focused on total DALYs as the primary measure of disease burden, although some studies have included other measures such as years of life lost (Stockmann et al., 2014). Most studies have followed Gross in looking at public research funding as the comparator, though some studies have been conducted on the alignment between disease burden and funding from the pharmaceutical industry (Jung et al., 2020).

This committee was tasked to answer a question that is related in some ways to the question of alignment between research funding and burden of

disease, although different in other ways. Key areas of difference include (1) a focus on therapeutic innovation rather than on all of health research; (2) a focus on unmet need for effective therapies, excluding need relating to lack of access; and (3) a broader mandate to address not only overall population burden but also burden relating to high-impact, low-frequency diseases, as well as variation in burden across different populations. Given this charge, an important foundational task is to present a clear conceptual framework for evaluating misalignment of investments in therapeutic innovations.

The committee proposes an overall rubric for identifying mismatch between investments in therapeutic innovation and disease burden or unmet need that defines underinvestment in a therapeutic area when all of the following conditions are met: (1) the therapeutic area meets one or more criteria for high disease burden; (2) the burden is insufficiently addressed by existing therapeutic options (i.e., there is an unmet need for effective therapies); and (3) the current level of investment in therapeutic development is insufficient to respond to the unmet need. For each of these conditions, this report seeks to provide a clear conceptual definition, as well as to discuss the data and measurement challenges associated with operationalizing metrics that are compatible with these conceptual definitions. This chapter focuses on the conceptual definitions and foundations. Chapter 3 will examine empirical data on areas of alignment or mismatch.

DISEASE BURDEN

Historically, public health measures for comparing the magnitude of different health problems have focused on measures of frequency, especially counts of deaths or crude population death rates. Tables of causes of death data can be traced back over several centuries, with early precedents in John Graunt’s analyses of bills of mortality in London (Connor, 2024), through the development of the first classification systems for causes of death by William Farr and others (Alharbi et al., 2021). A key development in capturing a more nuanced understanding of disease burden—capturing both the event of death and the importance of its timing—is attributable to Mary Dempsey’s research on tuberculosis (TB) mortality during the 1940s (Dempsey, 1947). Dempsey observed that many TB deaths occurred among younger adults and proposed that the health losses associated with tuberculosis mortality should be calculated in terms of the number of years individuals would have lived had they not died from TB. The “years of life lost” metric compared with a reference life expectancy measure became the foundation for the concept of premature mortality that has remained a central component of disease burden measurement. A number of variants of the years-of-life-lost concept followed Dempsey’s precedent (CDC, 1998).

The next fundamental expansion in concepts of disease burden was the development of summary measures of population health that captured health losses related to both mortality and morbidity. Research on health-related quality of life gathered momentum in the latter part of the twentieth century, with a proliferation of quality of life measurement instruments starting in the 1960s and 1970s. The quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) was introduced in the 1970s as a summary measure for the benefits of health interventions that captured improvements in both longevity and in health-related quality of life (Spencer et al., 2022). In 1993, the disability-adjusted life-year, or DALY, was introduced as a summary measure analogous to the QALY but used to quantify and compare the population health burden associated with different causes of disease and injury (Chen et al., 2015). The first major application of DALYs to compute the global burden of disease appeared in the 1993 World Development Report (World Bank, 1993). An influential Institute of Medicine report in 1998 (IOM, 1998b) examined some of the key conceptual, empirical, and ethical issues around construction of summary measures of population health. Work at the World Health Organization during the 1990s and 2000s continued to develop frameworks and applications for use of DALYs and other summary population health measures to quantify disease burden at global and national scales (Murray et al., 2002).

In the 1990s, the World Bank commissioned the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study to systematically estimate disability and death resulting from specific causes. The GBD study and its future iterations, while not comprehensive, are singular in their simultaneous immense scope and granularity of data (Murray, 2022). As of 2015, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), which serves as the coordinating center for GBD reports, has taken on the production of regular updates on disease burden using DALYs (IHME, n.d.).

Framework for Operationalizing the Definitions of Disease Burden

To operationalize disease burden for the purposes of the statement of task, the committee reviewed a range of previous efforts to define frameworks for the measurement of disease burden. One example is the framework published by the RTI group (Honeycutt et al., 2011), which characterizes disease burden in terms of the frequency of disease occurrences and their impact on individuals and populations. In this framework, disease occurrence is expressed by epidemiologic measures, namely, the incidence and prevalence of a disease. The committee acknowledges that the burden of a disease depends not only on how many people acquire a disease (incidence) but also on how long the people live with the disease (duration), and that the number of people currently living with a disease (prevalence) is a function

of both incidence and duration. The severity of a disease, irrespective of chronicity, has a major effect on both the quality of life and economic well-being at the individual and societal levels. While important to the concept of disease burden, emerging threats, such as multidrug-resistant bacteria infections, are not covered in this chapter, though the topic is discussed in Chapter 4. To guide the task for this report, the committee adopted an operational definition of disease burden as the total, cumulative consequences of a defined disease, which in its broadest formulation includes health, social aspects, and costs to society. The measures for operationalizing this definition are discussed below.

Measures of Disease Burden on Society

Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs)

DALYs were developed as a measure of the population health effect caused by fatal and nonfatal health outcomes (Berkley et al., 1993). As such, the arithmetic components for calculating DALYs are years of life lost (YLLs) attributable to premature death and years lived with disability (YLDs) associated with nonfatal injuries and diseases. A number of critiques of DALYs have challenged key conceptual and methodological aspects of the measure as it has evolved. Early iterations of the DALY were criticized for using health experts’ assessments of disability, rather than the lived experiences of people living with a disability (Grosse et al., 2009). Because of this critique, weights for nonfatal outcomes in DALYs have been based on population surveys since the 2010 iteration of the GBD study (Salomon et al., 2012). DALYs have also been criticized for devaluing the consequences in older versus younger persons that results from measuring premature mortality as a function of age at death. Furthermore, given that measures of DALYs capture the perceived desirability of health states, these measures may not be fully representative of the actual functional limitations or social participation restrictions (Grosse et al., 2009). Finally, DALYs are frequently criticized for the utilitarian nature of aggregate measures of population health as opposed to measures that include equity and distributional considerations. While some have proposed alternatives to DALYs, including the healthy life-year (Hyder et al., 1998) or narrower measures of avoidable mortality (Garcia et al., 2024; OECD, 2022) no alternative metrics have been applied with either the scope or the frequency that is found with the application of DALYs in comprehensive, standardized, and regularly updated cycles of disease burden measurement.

Quality-Adjusted Life-Years (QALYs)

The QALY measure is commonly used in the economic evaluation of health programs, medications, and technologies (Ferko et al., 2008; Touré et al., 2021). This composite measure estimates the years of life remaining for a patient following a particular treatment, medication, or technology, by weighing each year with a quality-of-life score based on multiple dimensions such as mobility, pain, and anxiety/depression. A score of 0 indicates death, while 1 indicates perfect health (Touré et al., 2021). Thus, QALYs allow for comparisons of benefits between two treatments when the outcomes and adverse effects vary (Rand and Kesselheim, 2021). There are numerous instruments available to assess QALYs (Tonin et al., 2021). Importantly, QALYs are based on average population outcomes, and as such, should be applied to treatments at a population level rather than at the individual patient level (Rand and Kesselheim, 2021). Although conceptually similar to DALYs, the QALY is not typically used as a direct measure of disease burden because it is not a standardized normative metric, so there are no comprehensive tabulations of QALYs by disease comparable to those that exist for DALYs.

The use of QALYs is controversial, with one study noting concerns that the measure is not patient focused, has the potential to be used as rationing tools by health insurers, and may be “dehumanizing” (Neumann and Cohen, 2018). Another literature review categorized criticisms of QALYs into three broad categories related to methodological issues, neutrality, and potential for discrimination (Rand and Kesselheim, 2021). Regarding methodological issues, some scholars have raised concerns about the reliability and validity among QALY instruments, the difficulty with self-reporting for some populations, and the insensitivity of the measure to specific conditions or changes in health, among other areas (Rand and Kesselheim, 2021). It is important to note that because of the instrument’s weighting methods, Congress prohibited the use of QALYs in making coverage or reimbursement decisions and in pricing negotiations.1,2 Regarding neutrality, the literature indicates that QALYs may ignore the distribution of health conditions as well as the initial severity of the conditions. The aggregation of outcomes is also a challenge with QALYs, with the measure not drawing a clear distinction between the ability to save or extend lives and improve quality of life.

Despite limitations of the metric, QALYs are often used as a unit of health benefit for intervention evaluation and cost-effectiveness analysis in the United States and worldwide. However, economists in the United

___________________

1 42 USC 1320e–1. Limitations on certain uses of comparative clinical effectiveness research. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/1320e-1.

2 42 USC 1320f–3. Negotiation and renegotiation process. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/1320f-3.

States have recently advanced alternative measures to try to account for criticisms of the QALY. For example, the equal value of life-years gained, one proposed alternative, assigns an equal value to all life-years gained and incorporates improvements in quality of life, regardless of age or disability (ICER, 2020; O’Day et al., 2021).

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

Health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) measures are designed to capture information on an individual’s health and its effect on related areas, such as physical functioning, emotional or mental functioning, social functioning, pain, fatigue, and other symptoms (Lapin, 2020; Leininger et al., 2023). These measures have been used to inform clinical management decisions and health policy, evaluate patient outcomes, monitor patient progress and treatment response, and assess the effects of medical interventions (Lapin, 2020). A number of studies have validated the use of HRQoL across clinical and community settings, and a wide variety of validated instruments is available to assess HRQoL (Lapin, 2020; Slabaugh et al., 2017; Zack, 2013).

Typically, HRQoL measures are not used on their own as a measure of burden. Rather, they are components of summary measures like DALYs and QALYs and provide an assessment of patients’ condition and functional status. Since these measures do not capture burden over time or mortality risk, they are not candidates to serve as a summary measure of disease burden, but HRQoL can provide insight into key dimensions of burden at points in time.

Despite research supporting the use of HRQoL, a number of concerns have been raised about these measures. For example, the wide range of instruments available increases the potential for inconsistent use and poor replicability by researchers (Kaplan and Hays, 2022). Additionally, patients can interpret and respond to HRQoL instruments based on their own experiences and values, thus making responses variable and challenging to interpret (Lapin, 2020). Missing data has also been identified as an issue (Lapin, 2020).

Underreporting is another challenge. In studies of HRQoL reporting within cancer clinical trials, Gupta et al. (2022) found that there was significant underreporting of HRQoL outcomes (< 50 percent) associated with U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug approvals. Most of the trials reviewed by the authors reported HRQoL data in an ancillary paper or abstract, and at a time later than the FDA approval. Of those included in the study, 10 percent of approved drugs, based on response rates, showed improvement in HRQoL in registration trials (Gupta et al., 2022). There has also been limited reporting of HRQoL in the labels of drugs approved for rare diseases (Lanar et al., 2020).

Another issue is the potential to exclude certain populations and diseases in the available clinical literature. For example, patients who are not able to provide information or respond to the HRQoL instruments, such as those with cognitive, linguistic, or motor deficits, may be excluded from related data, resulting in selection bias and an inability to provide a representative sample of patients (Lapin, 2020). Another study assessed the validity, reliability, and responsiveness of HRQoL in over 46,000 high-cost, high-need (HCHN) adults (Leininger et al., 2023). The results indicated that an assessment of physical health exhibited robust measure validity, reliability, and responsiveness across all age groups, while the mental health scale did not (Leininger et al., 2023). The authors noted that patient-reported health outcomes remain poor in HCHN populations, even after health care usage regresses (Leininger et al., 2023).

Economic Measures of Disease Burden on Society

The metrics discussed so far are all intended to capture a construct of disease burden that relates strictly to health rather than encompassing economic outcomes. In contrast, there are proposed measures of burden that focus exclusively on these economic outcomes. These measures aim to calculate diseases’ economic cost to society. It is important to recognize that society as a whole bears the cost of U.S. disease burden, through higher insurance premiums and taxes to cover health care system spending, and these costs are likely to increase without addressing unmet needs.

The most prominent of economic measure of disease burden is the cost-of-illness (COI) approach. COI studies have been undertaken since the middle of the twentieth century to quantify the economic impact of diseases on society (Cuningham, 2023). Typically these studies capture health care expenditures, lost productivity, cost of caregiving, and other direct and indirect costs of diseases. Some COI studies have focused on specific clusters of disease, such as cardiovascular disease, while others have been more general in scope. Guidelines for COI studies from NIH and the World Health Organization (WHO) have aimed to standardize methods (Honeycutt et al., 2011; WHO, 2016, 2021). However, a number of critiques of this approach have been presented, including concerns about prioritizing conditions based on their high costs rather than on their health impact, concerns about comparability across studies, and concerns about inequities in the use of economic measures that, for example, would place a greater weight on conditions that affect higher earners. In this report, the committee does not consider cost-of-illness measures as having primary relevance to its task of identifying unmet needs for therapeutic innovation.

Measures of Disease Burden on Individuals

Because measures of aggregate population-level burden reflect the combination of frequency or extent of occurrence in a population and the consequences of these occurrences, they are not well suited to identifying conditions that are particularly consequential for the individuals affected by them. The same aggregate burden could result from a common disease with a large burden per individual, or from a rarer disease with a high burden per individual. As a result, comparisons of population burden may underemphasize conditions that are relatively uncommon but responsible for substantial health losses to individuals. In the United States, a rare disease is defined as a condition affecting fewer than 200,000 (FDA, 2024). It is important to note that while these diseases are rare individually, collectively they may affect millions of Americans, and can be especially devastating—with a lengthy diagnostic odyssey, limited treatment options, and significant effects on families and caregivers. Population-level metrics can underestimate these factors and obscure areas of unmet need or disparities across populations. While these considerations are not unique to rare diseases—highly prevalent diseases such as dementia involve a high degree of individual and caregiver burden—this situation with rare diseases, some of which little has been done to characterize the underlying mechanisms of disease, needs to be balanced with disorders that affect millions of people.

Assessing individual disease burden can complement population-level information, such as the DALYs discussed above, to provide additional insight into unmet need or disparities. Individual burden can be assessed through patient-reported outcome measures (see, for example, Churruca et al., 2021) that incorporate symptom severity and quality-of-life impacts, as well as patient and caregiver perspectives. Qualitative information can offer important additional context about lived experience, challenges in diagnosis or treatment burden, effects on family and relationships, disruptions to careers and education, and more. See Box 2-1 for more discussion of patient engagement throughout the process of therapeutic development.

Variations in Disease Burden Across Different Populations

Variations in disease burden across populations have long been documented (HHS, 1985; IOM, 2003; NASEM, 2024). Disease epidemiology is known to vary in the United States across demographic attributes such as socioeconomic status, gender, age, and racial or ethnic group identity. For example, lower-income groups are at higher risk of chronic disease, including diabetes, heart disease, and chronic lung conditions (Blackwell et al., 2014; Gitterman et al., 2016; Healthy People 2030, n.d.) Associated with exposure to chronic stress, income-related health disparities are

BOX 2-1

Patient Engagement Throughout the Life Cycle of Drug Development

To better understand how to incorporate patient voices into measures of disease burden and unmet need, the committee held a panel focused on patient engagement (see full agenda in Appendix A) during which the committee heard from patient groups and experts in patient engagement. The content in this box is based on those presentations.

Speakers highlighted several challenges in patient engagement within industry. First, speakers encouraged incorporating patient perspectives from the study outset and avoiding retroactively seeking patient perspectives, which slows down development and can result in wasted time. “Although the purpose of medicines is to improve patients’ lives and to provide more effective health care, current patient involvement during medicine development and life cycle management is fragmentary at best, and mostly confined to postlaunch or late-stage clinical development” (Hoos et al., 2015, p. 930). Sometimes acquisitions occur for a promising drug where the science is there, but speakers acknowledged that it does not address an outcome that is important to the patient. Speakers also described barriers in communication, specifically that patient groups are overwhelmed with requests to replicate the same work. A proposed solution to this type of redundancy could be in the form of easily accessible repositories, such as resources from Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2021a) and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute that could be expanded (PCORI, n.d.).

To address these challenges, Marc Boutin, the global head of patient engagement at Novartis, cited the company’s Five Decision Point patient engagement framework that spans the entire life cycle of medicine development and incorporates patient insight early in therapeutic development (Patients as Partners, 2023). This framework is based on work from University of Maryland’s Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (M-CERSI, 2025).

- Target product profile definition: Engage patients to understand their needs and preferences to shape the desired characteristics of a new therapy.

- Clinical trial design: Collaborate with patients to codesign trials, ensuring protocols are patient friendly and relevant.

- Regulatory review preparation: Incorporate patient input to inform benefit–risk assessments during regulatory submissions.

- Market access strategy: Engage patients to inform pricing, reimbursement, and access strategies, facilitating equitable access.

- Postmarket activities: Involve patients in real-world effectiveness monitoring and gathering feedback for continuous improvement.

By engaging patients at the beginning of research through clinical development, Boutin cited faster drug development times that cut as much as 2.5–3.5 months off the clinical development timeline. In addition to saved time, early and consistent patient engagement generated $250 million in savings for the company and created a net present value between $850 million and $1.5 billion.

SOURCE: Panelists’ remarks to the committee in public session on December 16, 2024.

documented across the life course. In particular, experiencing childhood poverty is associated with nutritional deficits, developmental delays, and other adverse health outcomes in the long term (Gitterman et al., 2016; Pascoe et al., 2016). Poverty contributes to higher mortality and lower life expectancy for those with lower incomes (Healthy People 2030, n.d.; Khullar and Chokshi, 2018). In addition to health consequences, people with lower incomes face barriers to accessing health care or paying for treatments (Healthy People 2030, n.d.; Khullar and Chokshi, 2018).

In another example of varied disease burden, rural populations tend to have higher rates of smoking (and associated chronic illnesses), high blood pressure, obesity, and unintentional injury deaths (CDC, 2024a); these risks are compounded by less accessible health care and lower health care usage (Nuako et al., 2022). Conversely, urban populations are at higher risk of exposure to air pollution, but this exposure is differentially distributed—lower income, Hispanic, and Black populations are more likely to live in urban areas with high levels of pollutants and are thus more at risk for negative health impacts (American Lung Association, 2023; Kerr et al., 2024).

Similarly, disease burden and health outcomes often vary across racial and ethnic groups, typically caused by differential exposure to positive and negative social determinants of health or other factors associated with race and ethnicity, rather than any inherent biological difference. For instance,

maternal mortality rates are highly disproportionate, with pregnant women who identify as Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander being over three times more likely than White individuals to experience a pregnancy-related death (CDC, 2024b; Hill et al., 2024). In another recent report, American Indians and Alaska Natives have the lowest average estimated life expectancy at birth compared to other racial and ethnic groups in the United States (Arias et al., 2023). There are numerous other examples of variations in disease burden across populations (see NASEM, 2024).

In sum, health disparities can stem from a variety of factors including historical context, environmental exposures, and social determinants of health. These variations in disease burden can illuminate different areas of unmet need where innovation could help close gaps. For example, innovative point-of-care diagnostics and treatments could make higher-quality care more accessible for rural populations who reside far from urban medical centers.

The Effect of Comorbidities

In evaluating the burden of individual diseases, it is important to consider not just the burden directly related to the disease itself, but also the potential for one disease to increase the risk of developing additional comorbid diseases or to adversely affect the course of existing comorbid disease(s). Multimorbidity, defined as two or more coexisting conditions, affects 58.4 percent of adults in the United States (Mossadeghi et al., 2023). The prevalence of multimorbidity increases with age but affects people across all age spectra; among those aged 20–29 years, the prevalence is 22.2 percent (Mossadeghi et al., 2023).

Failure to consider the effect of individual diseases on the occurrence or course of comorbid diseases and related downstream health-related expenditures could result in substantial undervaluations or, less commonly, overvaluations of the burden for a given disease. Among people with multiple comorbid chronic diseases, overall spending on health care was multiplicative, meaning that spending for the combination of diseases was significantly higher than for the diseases individually, for more than 60 percent of the U.S. population (Chang et al., 2023).

Major depressive disorder provides an instructive example of how one disease can increase the risk of developing other diseases, adversely affect the course of existing comorbid diseases, and thereby increase downstream health-related expenditures (Box 2-2).

Beyond depression, several other mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for a range of medical conditions (Rapsey et al., 2015; Scott et al., 2016). A population-based cohort study of nearly

BOX 2-2

Exemplar: Major Depressive Disorder

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is considerably more common in people with common general medical conditions than it is in people without them (Walker et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2017). While the prevalence of MDD is approximately 5 percent in the general population (GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2017), its prevalence is substantially higher among adults with type 2 diabetes (28 percent) (Khaledi et al., 2019), myocardial infarction (29 percent) (Doyle et al., 2015), cerebrovascular disease (~18 percent) (Mitchell et al., 2017), or cancer (8–24 percent) (Krebber et al., 2014).

A recent large (n = 130,652) multicohort study of UK Biobank participants highlights the contribution of depression to excess hospitalizations for a range of medical conditions (Frank et al., 2023). In a series of adjusted Cox proportional hazards regressions, severe or moderately severe depression was associated with increased hazards-of-incident hospital admissions for multiple conditions, including bacterial infections and ischemic heart disease. There is also evidence that depression accelerates the progression of comorbid diseases. Among participants in the UK Biobank study with prevalent heart conditions, those with depression at baseline had nearly twice the risk of hospital admission for circulatory conditions during follow-up as those without depression at baseline (Frank et al., 2023).

Several mechanisms may account for why individuals with depression are at increased risk for these and other diseases. For example, the elevated rates of obesity (de Wit et al., 2010) and diminished physical activity (Schuch et al., 2017) seen among adults with depression could contribute to their elevated risk of developing type 2 diabetes (Yu et al., 2015), stroke (Pan et al., 2011), or coronary artery disease (Cao et al., 2022). Of course, the co-occurrence of depression with these and other medical conditions might also be confounded by earlier exposures to childhood abuse, socioeconomic adversities, substance use, or shared environmental or genetic risk factors. A review identified 24 candidate genes that are shared between depression and cardiovascular disease (Amare et al., 2017). For these reasons, attributing to depression all the excess increased risk burden of comorbid medical conditions observed in these epidemiological studies risks overestimating the global disease burden of depression.

A similar challenge exists in deciding what fraction of the increased burden associated with accelerated comorbid disease progression to assign to depression. It is possible that by reducing adherence to treatment (Gold et al., 2020) or diminishing aspects of self-care (Morgan et al., 2006), depression tends to accelerate the progression of several chronic preexisting diseases. Again, however, shared environmental and genetic factors may contribute to the liability to develop depression and to a poorer course of comorbid medical conditions.

6 million individuals from Danish registries revealed that in addition to mood disorders, there are strong prospective associations of substance-use disorders, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders, personality disorders, intellectual disabilities, developmental disorders, behavioral disorders, and organic disorders with many general medical conditions (Momen et al., 2020). Research indicates that the burden of mental health disorders is manifested not only through direct effects on health care and health care costs, reduced productivity, and diminished quality of life, but also indirectly through increased risks of developing other general medical conditions and accelerated progression of comorbid medical conditions. Because mental health disorders commonly have adverse effects on health behaviors including self-care, it is not surprising that many mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk of developing general medical conditions and poorer outcomes of existing persistent medical conditions.

The possibility of bidirectional associations between two diseases complicates the attribution of disease burden to a single disease. For example, individuals with rheumatoid arthritis are at increased risk of developing depression, while those with depression are also at increased risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (Lu et al., 2016). The mechanisms underlying these connections are incompletely understood. However, they might involve rheumatoid arthritis-mediated physical limitations and work restrictions for the former association, and depression-mediated dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary adrenal axis related expression of inflammatory cytokines for the latter.

In addition to mental health conditions, there are also many important examples of general medical conditions being strong risk factors for related medical conditions. A few well-known examples include hypertension and cardiovascular disease (including stroke, peripheral arterial disease, coronary artery disease, renal disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation) (Alloubani et al., 2018; Glovaci et al., 2019), ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer (Lakatos and Lakatos, 2008), and peptic ulcer disease with gastric cancer (Hansson et al., 1996).

The effect of diabetes mellitus highlights how one condition can affect downstream outcomes for unmet needs. Diabetes affects 38.4 million people in the United States., which represents more than 11 percent of the entire population (NIDDK, 2024). Of these, 352,000 are children and adolescents under the age of 20.

It is well established that diabetes leads to microvascular complications: retinopathy (diabetes is the leading cause of blindness), neuropathy, and nephropathy/kidney disease (Klein, 1995). Additionally, diabetes leads to macrovascular complications, including coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, and cerebrovascular disease (Arnold et al., 2022). These risks include those of acute myocardial infarction (Sarnak et al., 2019)

and stroke (Kaze et al., 2022). Furthermore, there is an additive effect of the microvascular complications on the macrovascular complications; for example, kidney disease among people with diabetes also independently increases the risk of acute myocardial infarction and stroke. Therefore, diabetes leads to additional comorbidities and these comorbidities also lead to adverse downstream health outcomes for patients. As another example of these complex relationships, one of the strongest recommendations for patients who develop these macrovascular complications is physical activity (which is well established to reduce the risk of acute myocardial infarction and stroke). However, patients with diabetes, who are at much higher risk of developing neuropathy, may then be limited in their ability to perform physical activity—including walking (Kanade et al., 2006).

This cascade of comorbidities and sequelae of diabetes also increases health care spending beyond just care for diabetes. It is estimated that the total cost of diagnosed diabetes in the United States in 2022 was $412.9 billion (Parker et al., 2024). Attributable primarily to the vascular complications of diabetes, the mean annual all-cause costs for people with type 2 diabetes were nearly 2.6 times higher than control patients without diabetes in the year after diagnosis and stabilized to between 1.5 and 1.6 times higher in the 2 to 8 years postdiagnosis (Visaria et al., 2020).

In summary, the occurrence of one disorder commonly increases the risk of developing other disorders or adversely affecting the progression of comorbid disorders. The interlinked nature of disease processes poses a critical challenge to the accurate attribution of societal burden and spending on specific individual diseases. Investing in research to help dissect the complex causal pathways linking diseases to each other and to their progression will not only improve the targeting of preventive interventions but also improve the precision with which disease-specific burdens are estimated.

The Committee’s Approach to Assessing Disease Burden

In summary, these measures of disease burden all feature some measurements of the epidemiology, economic impact, and health-related quality of life of diseases. Given the multiple existing measures of disease burden, the committee did not create new measures but rather sought to use existing measures and data to help address and accomplish the statement of task. Moreover, considering the variety of ways that disease burden can be measured and analyzed, the committee recognized that there was no single method for assessing mismatch. As covered in this section, all quantitative measures of disease burden or health gains have a degree of subjectivity because they incorporate different assumptions or ethical judgments. Different approaches used to address disease burden could also stem from different priorities and hence yield varied results. Thus, the committee does

not propose a single metric or approach for determining mismatch between burden and investment, but instead considers applying several dimensions and factors, such as both population-level and individual burden, that would inform mismatch or alignment. Any prioritization system involves some kind of value judgments and trade-offs, but having clear and transparent metrics is important to move beyond the current system.

To improve the assessment of disease burden for the purposes of investment decisions, it is important to align on standardized disease and therapeutic categories for comparison. Similarly, given the long development time of therapeutics, informative assessments of disease burden will need to incorporate estimates of future burden. For instance, such estimates will be particularly useful in better understanding how climate-induced changes in the distribution of vector-borne infectious diseases will affect U.S. disease burden. Forecast scenarios will also reflect the steady evolution of demographic (e.g., life expectancy) and epidemiological (e.g., risk factors) changes that have been well characterized in previous retrospective analyses, such as the GBD decomposition analyses (GBD, 2024), as well as other drivers that are less predictable but could have important implications for unmet need. For example, future estimates are also necessary to account for the risk of low-probability, high-impact events, such as pandemics and natural disasters, even if their low probabilities make them inherently hard to predict.

In the following chapter, the committee analyzes available data to assess mismatch, to the extent possible given some data limitations (see Chapter 3).

UNMET NEED

Unmet need refers to treatment gaps or areas where therapies do not exist for a particular medical condition or existing therapies are either inadequate or inaccessible (Lodato and Kaplan, 2013). In cases where there are existing therapies, unmet need may arise in relation to limitations in efficacy, safety, tolerability, convenience, or accessibility. A focus on unmet need highlights the medical areas where improved treatment options are needed to more effectively address patient health concerns (Vreman et al., 2019).

Unmet need exists when a patient population lacks adequate therapeutic interventions to effectively manage or cure a condition. This definition centers on the needs of patients and helps identify areas of therapeutic development to prioritize in order to address these unmet needs and to improve associated disease burden. FDA guidance similarly defines unmet medical need as “a condition whose treatment or diagnosis is not addressed adequately by available therapy” (FDA, 2014, p. 4). If approved therapies exist, new treatments could still address FDA’s definition of unmet medical

need under several conditions such as having an improved effect on a serious health outcome, improving outcomes in patients who did not respond to available therapy, and reducing the potential for harmful drug interactions or side effects, among others (FDA, 2014).

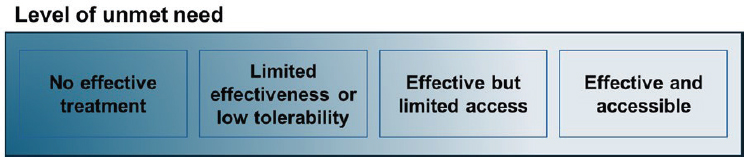

To summarize this discussion and to define the scope of this report, the committee considered a continuum of unmet need (Figure 2-1), recognizing that this is a generalization that does not capture the nuances of what drives unmet need. (See Chapter 4 for a discussion of factors that contribute to misalignment between innovation, disease burden, and unmet need.) On one end of the spectrum is “no effective treatment”—that is, there are no currently approved therapeutic treatment options for a particular disease condition. At the other end of the spectrum are conditions with effective and accessible treatments. Between these points is a range of conditions for which treatments have limited effectiveness or low tolerability. As the examples discussed in this section demonstrate, existing treatments may be associated with residual unmet need for a variety of reasons (e.g., low tolerability, difficulty managing treatment regimens, insufficient improvements to health outcomes). In this framework, effectiveness is considered a composite of efficacy and tolerability that represents not only how well a treatment works under ideal conditions (efficacy) but also how well it is tolerated by patients (tolerability) under real-world conditions.

Limited access to or use of existing therapeutics, in general or for subgroups of the population, can also contribute to unmet need, though as noted in Chapter 1, considerations for individual access are considered out of scope for this report. Some dimensions of access are inseparable from notions of unmet need relevant to innovation priorities, including features of the technology itself, the clinical context in which it is used, and the current drug pricing and reimbursement system. These dimensions are discussed more fully in the chapters that follow.

NOTE: The committee considered a continuum of unmet need, categorized as a medical condition or disease for which there are (1) no existing effective therapeutic treatment options, (2) existing therapeutic solutions with limited effectiveness, or (3) existing effective and tolerable therapies that have limited access.

However, this report will not consider in detail the broader social, economic, and behavioral determinants that influence patient access and use of existing treatments. Such determinants include disparities in our health care system overall that lead to underdiagnosis and inadequate treatment, economic barriers associated with out-of-pocket costs of the drugs and associated follow-on care, disparities in education and health literacy that lead to substandard care receipt, and the neighborhood and built environment, which can limit access to preventive services and health promoting behaviors. A better understanding of how these determinants and others affect access to and use of existing therapeutics will be critical if there is to be a significant reduction in unmet need, but these themes are beyond the scope of this report.

Factors That Contribute to Unmet Need

The committee recognizes that it is challenging to develop a uniform understanding of what areas constitute an unmet need given the many factors that can contribute to it. Major depressive disorder or schizophrenia, for example, each have a large number of FDA-approved pharmacological treatments, but these medications yield only modest reductions in symptoms and functional improvement (Ormel et al., 2022). In the case of schizophrenia, the most widely used medications commonly result in adverse metabolic effects contributing to substantial unmet need for safer options (Chang et al., 2021). In other conditions, therapeutic effectiveness may be limited to certain subgroups of the population based on the severity of disease presentations, subtypes of disease, or treatment resistance. With hypercholesterolemia, for instance, statins are highly effective in lowering lipid levels in a large segment of the population (Feingold, 2024). However, a significant percentage of hyperlipidemic patients, including those with familial hypercholesterolemia, are unable to reach their LDL-goals, despite adherence to statin medications (Feingold, 2024).

When innovative PCSK9 inhibitors gained FDA approval, which are effective for familial hypercholesterolemia, payer coverage was limited, given the lack of cost-effectiveness research available at the time of launch, which narrowed access to individuals who could not achieve lipid goals on statins, thereby contributing to unmet clinical need for others who may experience greater benefit from PCSK9 compared to statins (Baum et al., 2017). The time course of disease can also limit the effectiveness of available therapeutics. For instance, antiparasitic agents, such as praziquantel and metronidazole, which are indicated in neglected tropical diseases, such as schistosomiasis and amebiasis, respectively, are effective only initially, before the parasites develop resistance or tolerance, which makes them ineffective over the long term (Eastham et al., 2024; Shrivastav et al., 2021).

Unfavorable safety profiles and low tolerability can also limit the ability of existing therapeutics to address disease burden and can result in residual unmet need. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) offers an example. Nintedanib (OFEV) and pirfenidone (Esbriet) are associated with significant adverse effects yet remain the primary antifibrotic options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which is a condition with a high associated mortality (He et al., 2024). A next generation of pirfenidone, a deuterated analogue, recently passed FDA phase 2 clinical trials with an improved safety and tolerability profile (Waldron, 2024). While not entirely novel, these improvements demonstrate innovation and may make the drug better suited to the IPF patient population, potentially helping to reduce unmet need.

Available therapies may also not be able to address unmet need because of problems related to clinical distribution, use, and adherence. Patients with schizophrenia, for instance, who may not be aware of their need for treatment, often present with limited adherence to treatment regimens, which prevents them from benefiting from antipsychotic agents (Olfson et al., 2006). As another example, medications that require refrigeration or cold-chain management may be limited in addressing disease burden in underserved areas that lack the infrastructure to support cold-chain requirements or for people who lack stable housing (Deloitte, 2023; IOM, 1988). Finally, the committee recognizes that unmet need may result not only from lack of effective treatment options, but in some cases from lack of accurate diagnostics that enable timely and precise identification of treatment need, as well as accurate predictive information on patients who are most likely to respond to a specific treatment.

An illustrative example of how unmet need reflects more than simply the availability of efficacious therapies, and how it relates to access and adherence, is the persistent burden of HIV infection in the United States and globally despite the development of highly effective preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). In 2012, the first PrEP medication was approved by FDA (Gilead, 2012). A major advance was made in 2021 with the introduction of a long-acting injectable PrEP (FDA, 2021b). While both forms of administration have been shown to be over 99 percent effective in reducing infection when taken as prescribed, one study showed that, in practice, the risk of HIV infection was 66 percent lower among those using the injectable versus oral PrEP; the difference was largely attributable to lower adherence to the oral (once a day) regimen versus the long-acting injectable drug, which is administered once every 2 months (Landovitz et al., 2021). Other formulation and delivery options are being tested and show promise, including HIV self-testing-supported models of oral PrEP delivery that rely on self-testing and can reduce the number of needed clinical visits (Kiptinness et al., 2022). The contrast in effectiveness between the two different forms

of PrEP illustrates well how unmet need may persist even when effective therapies are available, and technological innovation to reduce unmet need can do so by addressing barriers to access and adherence.

Yet despite the availability of multiple PrEP options, fewer than one-quarter of the estimated 1.2 million people in the United States who could benefit from PrEP receive prescriptions (Powder, 2022). Once PrEP is prescribed, adherence can be low or not sustained over long periods of time, especially with the oral PrEP (Ó Murchu et al., 2022). Barriers to both access and adherence include lack of awareness of one’s risk and how PrEP can help reduce that risk, HIV-related stigma, access to health care providers who are knowledgeable about the benefits of PrEP, high costs and inadequate insurance coverage, and perceived concerns about side effects which include headaches, fatigue, and gastric pain, but are usually mild and transitory. As one review concluded: “The future of PrEP adherence lies in person-centered approaches to service delivery that meet the needs of individuals while creating supportive environments and facilitating health-care access and delivery” (Haberer et al., 2023, p. 1).

In summary, unmet need comprises a lack of available treatments and deficiencies in available treatments. In contrast, disease burden encompasses the overall impact of a medical condition on patient populations and society. Both unmet need and disease burden are important concepts for understanding the gaps in health care and developing innovative solutions to improve outcomes.

INVESTMENT IN THERAPEUTIC INNOVATION

The public and private sectors play complementary roles in supporting and conducting biomedical research and development (R&D) in the United States. The public sector, through federal agencies such as the NIH and the Department of Defense, is the largest funder of basic research,3 and the private sector primarily supports and engages in drug discovery and development activities, such as clinical testing, incremental innovation (Barbosu, 2025), and product differentiation—activities that largely follow from basic research (Congressional Budget Office, 2021; Simoens and Huys, 2022).

Public investment in basic and applied biomedical research has contributed significantly to the development of new drugs (Galkina Cleary et al., 2018, 2023). As one study notes, public-sector researchers have “performed the upstream, basic research that elucidated the underlying mechanisms of disease and identified promising points of intervention”

___________________

3 Basic research, also sometimes called basic science or pure research, is a type of research that seeks to uncover and understand fundamental mechanisms and phenomena—for example, about health and disease. This work typically informs more applied research.

(Stevens et al., 2011, p. 535). When one accounts for indirect support such as basic science research on drug targets, NIH funded projects related to every new FDA-approved drug from 2010 to 2016 (Galkina Cleary et al., 2018). Moreover, although the public sector is known to predominantly invest in basic research, one study showed that one in four new drugs had some later-stage research contribution (usually related to the drug’s initial discovery or synthesis, and not always financial) from institutions such as universities that rely heavily on public support or from start-ups spun out of these publicly supported research institutions (Nayak et al., 2019). Public funding is less likely to directly support patentable aspects of new drugs; for example, fewer than 10 percent of drugs approved from 1985 to 2022 had any patents based on federal funding (Ouellette and Sampat, 2024). But public-sector investment has been shown to generate and amplify additional private-sector investment in biomedical research. For example, one study found that rather than “crowding out” private investment, each $10 million increase in NIH funding leads to 2.3 additional private-sector patents (Azoulay et al., 2019).

In addition to federal agencies, public-sector contributors to biomedical R&D include universities, international organizations, charities, and crowd-funding, while private-sector entities include venture capital funds, pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, private foundations and nonprofit organizations, and private research centers (Simoens and Huys, 2022). In 2020, funding for medical and health R&D investments in the United States came from the following entities (Research!America, 2022):

- 66 percent from industry;4

- 25.1 percent from federal government;

- 6.9 percent from academic and research institutions;

- 1.2 percent from foundations, voluntary health associations, and professional societies; and

- 0.9 percent from state governments.

Private-sector investment in R&D can come from a variety of sources, including in-house asset development at established biopharmaceutical companies, company mergers and acquisitions, and venture capital firms (SiRM et al., 2022). For-profit private-sector funding for biopharmaceutical research is driven largely by a return-on-investment analysis, determined by the amount of expected revenue, cost, and policies influencing its development (Congressional Budget Office, 2021). Decisions about new drugs are generally made within a set of three different contexts: scientific opportunity,

___________________

4 These investments do not include funding directed toward industry from other sources (Research!America, 2022).

market assessment (including medical need), and available and required resources. As private investment requires a return on investment within a predetermined time and a well-understood risk profile, some strategies and assessment for investment are centered on decreasing the timeline of R&D, decreasing the risk intrinsic in the discovery and development of new effective drugs, and increasing the willingness to pay from target payers and/or populations.

Not all private-sector R&D investment is motivated by return on investment. Private nonprofit organizations, including those that focus on specific disease areas, also fund biomedical R&D in support of their individual missions. These investments can be critical for advancing research to a stage where for-profit investors begin to see opportunities for commercialization (Graddy-Reed, 2020).

The public and private sectors are both critical for advancing drug innovation in the United States. Public investments help understand disease mechanisms that contribute to important novel drug targets and innovations from the private sector that can help reduce unmet needs.

REFERENCES

Alharbi, M. A., G. Isouard, and B. Tolchard. 2021. Historical development of the statistical classification of causes of death and diseases. Cogent Medicine 8(1):1893422.

Alloubani, A., A. Saleh, and I. Abdelhafiz. 2018. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus as a predictive risk factors for stroke. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome 12(4):577–584.

Amare, A. T., K. O. Schubert, M. Klingler-Hoffmann, S. Cohen-Woods, and B. T. Baune. 2017. The genetic overlap between mood disorders and cardiometabolic diseases: A systematic review of genome wide and candidate gene studies. Translational Psychiatry 7(1):e1007.

American Lung Association. 2023. Disparities in the impact of air pollution. https://www.lung.org/clean-air/outdoors/who-is-at-risk/disparities (accessed February 19, 2025).

Arias, E., J. Xu, and K. Kochanek. 2023. United States life tables, 2021. National Vital Statistics Report 72(12):1–64.

Arnold, S. V., K. Khunti, F. Tang, H. Chen, J. Cid-Ruzafa, A. Cooper, P. Fenici, M. B. Gomes, N. Hammar, L. Ji, G. L. Saraiva, J. Medina, A. Nicolucci, L. Ramirez, W. Rathmann, M. V. Shestakova, I. Shimomura, F. Surmont, J. Vora, H. Watada, and M. Kosiborod. 2022. Incidence rates and predictors of microvascular and macrovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes: Results from the longitudinal global DISCOVER study. American Heart Journal 243:232–239.

Azoulay, P., J. S. Graff Zivin, D. Li, and B. N. Sampat. 2019. Public R&D investments and private-sector patenting: Evidence from NIH funding rules. Review of Economic Studies 86(1):117–152.

Barbosu, S. 2025. The value of follow-on biopharma innovation for health outcomes and economic growth. Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. https://www2.itif.org/2025-follow-on-biopharma.pdf (accessed April 12, 2025).

Baum, S. J., P. P. Toth, J. A. Underberg, P. Jellinger, J. Ross, and K. Wilemon. 2017. PCSK9 inhibitor access barriers-issues and recommendations: Improving the access process for patients, clinicians and payers. Clinical Cardiology 40(4):243–254.

Berkley, S., J. L. Bobadilla, R. M. Hecht, K. Hill, D. T. Jamison, C. J. L. Murray, P. A. Musgrove, H. Saxenian, and J.-P. Tan. 1993. World development report 1993: Investing in health. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Blackwell, D. L., J. W. Lucas, and T. C. Clarke. 2014. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Vital Health Statistics 10(260):1–161.

Cao, H., H. Zhao, and L. Shen. 2022. Depression increased risk of coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.913888.

Carter, A. J. R., and M. Gevorkian. 2025. The persistence of very low correlations between NIH research funding and disease burdens. Public Health in Practice 9:100580.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1998. Mortality Weekly Report Supplements. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00001773.htm#:~:text=In%201947%2C%20as%20a%20supplement,remaining%20at%20death%20 (accessed January 23, 2025).

CDC. 2024a. About rural health. https://www.cdc.gov/rural-health/php/about/index.html (accessed February 19, 2025).

CDC. 2024b. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm (accessed February 19, 2025).

Chang, A. Y., D. Bryazka, and J. L. Dieleman. 2023. Estimating health spending associated with chronic multimorbidity in 2018: An observational study among adults in the United States. PLoS Medicine 20(4):e1004205.

Chang, S. C., K. K. Goh, and M. L. Lu. 2021. Metabolic disturbances associated with antipsychotic drug treatment in patients with schizophrenia: State-of-the-art and future perspectives. World Journal of Psychiatry 11(10):696–710.

Chen, A., K. H. Jacobsen, A. A. Deshmukh, and S. B. Cantor. 2015. The evolution of the disability-adjusted life year (DALY). Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 49(1):10–15.

Churruca, K., C. Pomare, L. A. Ellis, J. C. Long, S. B. Henderson, L. E. D. Murphy, C. J. Leahy, and J. Braithwaite. 2021. Patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMS): A review of generic and condition‐specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expectations 24(4):1015–1024.

Congressional Budget Office. 2021. Research and development in the pharmaceutical industry. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57126 (accessed April 12, 2025).

Connor, H. 2024. John Graunt F.R.S. (1620-74): The founding father of human demography, epidemiology and vital statistics. Journal of Medical Biography 32(1):57–69.

Cuningham, W. G. G. 2023. Innovative approaches to surveillance and quantifying the burden of bacterial infections and antibiotic resistance in northern Australia. Ph.D diss. Charles Darwin University, Australia.

Curry, C. W., A. K. De, R. M. Ikeda, and S. B. Thacker. 2006. Health burden and funding at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 30(3):269–276.

de Wit, L., F. Luppino, A. van Straten, B. Penninx, F. Zitman, and P. Cuijpers. 2010. Depression and obesity: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Research 178(2):230–235.

Deloitte. 2023. Access to medicine: Reach more patients through a deeper understanding of access issues. https://www.deloitte.com/fr/fr/Industries/life-sciences-health-care/analysis/access-medicine.html (accessed May 20, 2025).

Dempsey, M. 1947. Decline in tuberculosis. American Review of Tuberculosis 56(2):157–164.

Doyle, F., H. McGee, R. Conroy, H. J. Conradi, A. Meijer, R. Steeds, H. Sato, D. E. Stewart, K. Parakh, R. Carney, K. Freedland, M. Anselmino, R. Pelletier, E. H. Bos, and P. de Jonge. 2015. Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of sex differences in depression and prognosis in persons with myocardial infarction: A mindmaps study. Psychosomatic Medicine 77(4):419–428.

Eastham, G., D. Fausnacht, M. H. Becker, A. Gillen, and W. Moore. 2024. Praziquantel resistance in schistosomes: A brief report. Frontiers in Parasitology 3.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). 2014. Guidance for industry expedited programs for serious conditions—drugs and biologics. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Expedited-Programs-for-Serious-Conditions-Drugs-and-Biologics.pdf (accessed April 12, 2025).

FDA. 2021a. Clinical outcome assessment compendium. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/clinical-outcome-assessment-compendium (accessed March 19, 2025).

FDA. 2021b. FDA approves first injectable treatment for HIV pre-exposure prevention. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-injectable-treatment-hiv-pre-exposure-prevention (accessed May 21, 2025).

FDA. 2024. Rare diseases at the FDA. https://www.fda.gov/patients/rare-diseases-fda (accessed March 20, 2025).

Feingold, K. R. 2024. Cholesterol lowering drugs. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK395573/ (accessed May 19, 2025).

Ferko, N., M. Postma, S. Gallivan, D. Kruzikas, and M. Drummond. 2008. Evolution of the health economics of cervical cancer vaccination. Vaccine 26:F3–F15.

Frank, P., G. D. Batty, J. Pentti, M. Jokela, L. Poole, J. Ervasti, J. Vahtera, G. Lewis, A. Steptoe, and M. Kivimäki. 2023. Association between depression and physical conditions requiring hospitalization. JAMA Psychiatry 80(7):690.

Galkina Cleary, E., J. M. Beierlein, N. S. Khanuja, L. M. McNamee, and F. D. Ledley. 2018. Contribution of NIH funding to new drug approvals 2010–2016. Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences 115(10):2329–2334.

Galkina Cleary, E., M. J. Jackson, E. W. Zhou, and F. D. Ledley. 2023. Comparison of research spending on new drug approvals by the National Institutes of Health vs. the pharmaceutical industry, 2010–2019. JAMA Health Forum 4(4):e230511.

García, M. C., L. M. Rossen, K. Matthews, G. Guy, K. F. Trivers, C. C. Thomas, L. Schieb, and M. F. Iademarco. 2024. Preventable premature deaths from the five leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties, United States, 2010–2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 73:1–11.

GBD (Global Burden of Death study). 2024. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2021. Lancet 403(10440):2100–2132.

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. 2017. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990; 2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390(10100):1211–1259.

Gilead. 2012. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves Gilead’s Truvada for reducing the risk of acquiring HIV. https://www.gilead.com/news/news-details/2012/us-food-and-drug-administration-approves-gileads-truvada-for-reducing-the-risk-of-acquiring-hiv#:~:text=Truvada%20for%20a%20PrEP%20indication: (accessed May 21, 2025).

Gitterman, B. A., P. J. Flanagan, W. H. Cotton, K. J. Dilley, J. H. Duffee, A. E. Green, V. A. Keane, S. D. Krugman, J. M. Linton, C. D. McKelvey, and J. L. Nelson. 2016. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics 137(4):e20160339.

Glovaci, D., W. Fan, and N. D. Wong. 2019. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Current Cardiology Reports 21(4):21.

Gold, S. M., O. Köhler-Forsberg, R. Moss-Morris, A. Mehnert, J. J. Miranda, M. Bullinger, A. Steptoe, M. A. Whooley, and C. Otte. 2020. Comorbid depression in medical diseases. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 6(1):69.

Graddy-Reed, A. 2020. Getting ahead in the race for a cure: How nonprofits are financing biomedical R&D. Research Policy 49(8):104032.

Gross, C. P., G. F. Anderson, and N. R. Powe. 1999. The relation between funding by the National Institutes of Health and the burden of disease. New England Journal of Medicine 340(24):1881–1887.

Grosse, S. D., D. J. Lollar, V. A. Campbell, and M. Chamie. 2009. Disability and disability-adjusted life years: Not the same. Public Health Reports 124(2):197–202.

Gupta, M., O. S. Akhtar, B. Bahl, A. Mier-Hicks, K. Attwood, K. Catalfamo, B. Gyawali, and P. Torka. 2022. Is health-related quality of life (HRQoL) reporting keeping pace with new drug approvals in hematology and oncology: A five-year analysis of 245 drug approvals. Journal of Clinical Oncology 40(16Suppl):6519.

Haberer, J. E., A. Mujugira, and K. H. Mayer. 2023. The future of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence: Reducing barriers and increasing opportunities. Lancet HIV 10(6):e404–e411.

Hansson, L.-E., O. Nyrén, A. W. Hsing, R. Bergström, S. Josefsson, W.-H. Chow, J. F. Fraumeni, and H.-O. Adami. 1996. The risk of stomach cancer in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer disease. New England Journal of Medicine 335(4):242–249.

He, M., T. Yang, J. Zhou, R. Wang, and X. Li. 2024. A real-world study of antifibrotic drugs-related adverse events based on the United States Food and Drug Administration adverse event reporting system and vigiaccess databases. Frontiers in Pharmacology 15.

Healthy People 2030. n.d. Poverty. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/poverty (accessed February 19, 2025).

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 1985. Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black & Minority Health. Washington, DC: Task Force on Black and Minority Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

Hill, L., A. Rao, S. Artiga, and U. Ranji. 2024. Racial disparities in maternal and infant health: Current status and efforts to address them. KFF, October 25. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-current-status-and-efforts-to-address-them/ (accessed February 19, 2025).

Honeycutt, A. A., T. Hoerger, A. Hardee, L. Brown, K. Smith, and RTI International. 2011. An assessment of the state of the art for measuring burden of illness. Report prepared for Ansalan Stewart, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/76381/index.pdf (accessed April 11, 2025).

Hoos, A., J. Anderson, M. Boutin, L. Dewulf, J. Geissler, G. Johnston, A. Joos, M. Metcalf, J. Regnante, I. Sargeant, R. F. Schneider, V. Todaro, and G. Tougas. 2015. Partnering with patients in the development and lifecycle of medicines: A call for action. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science 49(6):929–939.

Hyder, A. A., G. Rotllant, and R. H. Morrow. 1998. Measuring the burden of disease: Healthy life-years. American Journal of Public Health 88(2):196–202.

ICER (Institute for Clinical and Economic Review). 2020. 2020-2023 value assessment framework. Boston, MA: ICER.

IHME (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation). n.d. GBD history. https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/about-gbd/history (accessed May 15, 2025).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1988. Homelessness, health, and human needs. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1998a. Scientific opportunities and public needs: Improving priority setting and public input at the National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1998b. Summarizing population health: Directions for the development and application of population metrics. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jung, Y. L., J. Hwang, and H. S. Yoo. 2020. Disease burden metrics and the innovations of leading pharmaceutical companies: A global and regional comparative study. Globalization and Health 16(1):80.

Kanade, R. V., R. W. M. Van Deursen, K. Harding, and P. Price. 2006. Walking performance in people with diabetic neuropathy: Benefits and threats. Diabetologia 49(8):1747–1754.

Kaplan, R. M., and R. D. Hays. 2022. Health-related quality of life measurement in public health. Annual Review of Public Health 43:355–373.

Kaze, A. D., B. G. Jaar, G. C. Fonarow, and J. B. Echouffo-Tcheugui. 2022. Diabetic kidney disease and risk of incident stroke among adults with type 2 diabetes. BMC Medicine 20(1):127.

Kerr, G. H., A. van Donkelaar, R. V. Martin, M. Brauer, K. Bukart, S. Wozniak, D. L. Goldberg, and S. C. Anenberg. 2024. Increasing racial and ethnic disparities in ambient air pollution-attributable morbidity and mortality in the United States. Environmental Health Perspectives 132(3):037002.

Khaledi, M., F. Haghighatdoost, A. Feizi, and A. Aminorroaya. 2019. The prevalence of comorbid depression in patients with type 2 diabetes: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis on huge number of observational studies. Acta Diabetologica 56(6):631–650.

Khullar, D., and D. A. Chokshi. 2018. Health, income, & poverty: Where we are & what could help. Health Affairs, October 4. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/briefs/health-income-poverty-we-could-help (accessed April 18, 2025).

Kiptinness, C., A. P. Kuo, A. M. Reedy, C. C. Johnson, K. Ngure, A. D. Wagner, and K. F. Ortblad. 2022. Examining the use of HIV self-testing to support prep delivery: A systematic literature review. Current HIV/AIDS Reports 19(5):394–408.

Klein, R. 1995. Hyperglycemie and microvascular and macrovascular disease in diabetes. Diabetes Care 18(2):258–268.

Krebber, A. M., L. M. Buffart, G. Kleijn, I. C. Riepma, R. de Bree, C. R. Leemans, A. Becker, J. Brug, A. van Straten, P. Cuijpers, and I. M. Verdonck-de Leeuw. 2014. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: A meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology 23(2):121–130.

Lakatos, P. L., and L. Lakatos. 2008. Risk for colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: Changes, causes and management strategies. World Journal of Gastroenterology 14(25):3937–3947.

Lanar, S., C. Acquadro, J. Seaton, I. Savre, and B. Arnould. 2020. To what degree are orphan drugs patient-centered? A review of the current state of clinical research in rare diseases. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 15(1):134.

Landovitz, R. J., D. Donnell, M. E. Clement, B. Hanscom, L. Cottle, L. Coelho, R. Cabello, S. Chariyalertsak, E. F. Dunne, I. Frank, J. A. Gallardo-Cartagena, A. H. Gaur, P. Gonzales, H. V. Tran, J. C. Hinojosa, E. G. Kallas, C. F. Kelley, M. H. Losso, J. V. Madruga, K. Middelkoop, N. Phanuphak, B. Santos, O. Sued, J. V. Huamaní, E. T. Overton, S. Swaminathan, C. d. Rio, R. M. Gulick, P. Richardson, P. Sullivan, E. Piwowar-Manning, M. Marzinke, C. Hendrix, M. Li, Z. Wang, J. Marrazzo, E. Daar, A. Asmelash, T. T. Brown, P. Anderson, S. H. Eshleman, M. Bryan, C. Blanchette, J. Lucas, C. Psaros, S. Safren, J. Sugarman, H. Scott, J. J. Eron, S. D. Fields, N. D. Sista, K. Gomez-Feliciano, A. Jennings, R. M. Kofron, T. H. Holtz, K. Shin, J. F. Rooney, K. Y. Smith, W. Spreen, D. Margolis, A. Rinehart, A. Adeyeye, M. S. Cohen, M. McCauley, and B. Grinsztejn. 2021. Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. New England Journal of Medicine 385(7):595–608

Lapin, B. R. 2020. Considerations for reporting and reviewing studies including health-related quality of life. Chest 158(1):S49–S56.

Leininger, L. J., M. Tomaino, and E. Meara. 2023. Health-related quality of life in high-cost, high-need populations. American Journal of Managed Care 29(7):362–368.

Lodato, E., and W. Kaplan. 2013. Priority medicines for Europe and the world: 2013 update report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Pp. 68–74.

Lu, M. C., H. R. Guo, M. C. Lin, H. Livneh, N. S. Lai, and T. Y. Tsai. 2016. Bidirectional associations between rheumatoid arthritis and depression: A nationwide longitudinal study. Science Reports 6:20647.

M-CERSI (University of Maryland Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation). 2025. Home page. https://cersi.umd.edu/ (accessed March 10, 2025).

Mitchell, A. J., B. Sheth, J. Gill, M. Yadegarfar, B. Stubbs, M. Yadegarfar, and N. Meader. 2017. Prevalence and predictors of post-stroke mood disorders: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of depression, anxiety and adjustment disorder. General Hospital Psychiatry 47:48–60.

Momen, N. C., O. Plana-Ripoll, E. Agerbo, M. E. Benros, A. D. Børglum, M. K. Christensen, S. Dalsgaard, L. Degenhardt, P. de Jonge, J. P. G. Debost, M. Fenger-Grøn, J. M. Gunn, K. M. Iburg, L. V. Kessing, R. C. Kessler, T. M. Laursen, C. C. W. Lim, O. Mors, P. B. Mortensen, K. L. Musliner, M. Nordentoft, C. B. Pedersen, L. V. Petersen, A. R. Ribe, A. M. Roest, S. Saha, A. J. Schork, K. M. Scott, C. Sievert, H. J. Sørensen, T. J. Stedman, M. Vestergaard, B. Vilhjalmsson, T. Werge, N. Weye, H. A. Whiteford, A. Prior, and J. J. McGrath. 2020. Association between mental disorders and subsequent medical conditions. New England Journal of Medicine 382(18):1721–1731.

Morgan, A. L., F. A. Masoudi, E. P. Havranek, P. G. Jones, P. N. Peterson, H. M. Krumholz, J. A. Spertus, and J. S. Rumsfeld. 2006. Difficulty taking medications, depression, and health status in heart failure patients. Journal of Cardiac Failure 12(1):54–60.

Mossadeghi, B., R. Caixeta, D. Ondarsuhu, S. Luciani, I. R. Hambleton, and A. J. M. Hennis. 2023. Multimorbidity and social determinants of health in the U.S. prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and implications for health outcomes: A cross-sectional analysis based on NHANES 2017–2018. BMC Public Health 23(1):887.

Murray, C. J. L., J. A. Salomon, C. D. Mathers, A. D. Lopez, and World Health Organization. 2002. Summary measures of population health: Concepts, ethics, measurement and applications. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Murray, C. J. L. 2022. The global burden of disease study at 30 years. Nature Medicine 28(10):2019–2026.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2024. Ending unequal treatment: Strategies to achieve equitable health care and optimal health for all. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nayak, R. K., J. Avorn, and A. S. Kesselheim. 2019. Public sector financial support for late stage discovery of new drugs in the United States: Cohort study. BMJ 367:I5766.

Neumann, P. J., and J. T. Cohen. 2018. QALYs in 2018—Advantages and concerns. JAMA 319(24):2473–2474.

NIDDK (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases). 2024. Diabetes statistics. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/diabetes-statistics (accessed October 30, 2024).

Nuako, A., J. Liu, G. Pham, N. Smock, A. James, T. Baker, L. Bierut, G. Colditz, and L.-S. Chen. 2022. Quantifying rural disparity in healthcare utilization in the United States: Analysis of a large midwestern healthcare system. PLoS ONE 17(2):e0263718.

Ó Murchu, É., L. Marshall, C. Teljeur, P. Harrington, C. Hayes, P. Moran, and M. Ryan. 2022. Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical effectiveness, safety, adherence and risk compensation in all populations. BMJ Open 12(5):e048478.

O’Day, K., D. J. Mezzio, and P. H. Xcenda. 2021. Demystifying ICER’s equal value of life years gained metric. Value & Outcomes Spotlight 7(1):26–28.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2022. Avoidable mortality: OECD/Eurostat lists of preventable and treatable causes of death. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/data/datasets/oecd-health-statistics/avoidable-mortality-2019-joint-oecd-eurostat-list-preventable-treatable-causes-of-death.pdf (accessed May 29, 2025).

Olfson, M., S. C. Marcus, J. Wilk, and J. C. West. 2006. Awareness of illness and nonadherence to antipsychotic medications among persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 57(2):205–211.

Ormel, J., S. D. Hollon, R. C. Kessler, P. Cuijpers, and S. M. Monroe. 2022. More treatment but no less depression: The treatment-prevalence paradox. Clinical Psychology Review 91:102111.

Ouellette, L. L., and B. N. Sampat. 2024. Using Bayh-Dole Act march-in rights to lower U.S. drug prices. JAMA Health Forum 5(11):e243775.

Pan, A., Q. Sun, O. I. Okereke, K. M. Rexrode, and F. B. Hu. 2011. Depression and risk of stroke morbidity and mortality. JAMA 306(11):1241.